#Marie Angeletti

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Marie Angeletti | Hamburg Society (Alex), 2021, Oil pastel on paper, 29 x 42 cm Magazine, Kunstverein in Hamburg, 2021

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Marie Angeletti

Witness

source: collectionarchive.tumblr.com

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Check out Marie Angeletti, TLYA 13_Tourists/ TLYA 14_Parrott/ TLYA 15_La Novice/ TLYA 16_SR 2014 (2014), From Saatchi Collection Benefit Auction

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marie Angeletti at Gaylord Apartments

http://dlvr.it/TBsYGk

0 notes

Text

In What Ways Can Speculative Engagement With The More Than Human World Contradict Human Exceptionalism?

Creating New Narratives Around the Position of Human Beings as Participants of Life During an Age of Mass Extinction.

The following writing was my dissertation submitted for the BA(Hons) Contemporary Art Practice Course at Gray’s School of Art. Please excuse the garbage title. It was fun to write this, but if I was to be self critical, I’m not too sure I really conclude the essay. Anyway, I’m pretty stoked on some of what I had to say, but some of it seems embarrassing already. It’s a long read and pretty tangental. I hope you make it through and find something interesting.

The following dissertation is dedicated with love to my Father.

“A cool wind blows in the city of beans.” - Fergus Connor, Gray’s School of Art Photography Studio Technician.

Introduction

It feels dumb to be hammering at a keyboard after writing the phrase age of mass extinction. I look out of my window and I can see my big, loud neighbour – the industrial structures of the international Port of Aberdeen – invade the personal space of my bigger but quieter neighbours the River Dee and the wild North Sea as a mild early season storm pushes through. The storm is an occasional visitor from whom we all recoil because it has a habit of getting so close that we can feel its breath. Herring Gulls and Common Seals defiantly travel into the bounds of the port, inaccessible to me by force of human law, but no one seems to mind them. There is a world full of life out there that is apparently becoming less and less alive with every passing moment but I am in here, in my little rented abode, that I cannot afford.

Shifting my gaze from window to screen, I question the value of what I am writing in spite of my strange enjoyment of the aggravatingly cortisol spiking activity. I am attempting to convince you that the conclusions I have arrived at after reading a dozen or so books are interesting enough to receive an abstract but quantitative mark of endorsement which may lead to a set of circumstances where I can buy, rather than borrow, a dwelling that I still cannot afford. A promise of more, when I know I want less.

The following words will explore the ways that self-contained attention and being inside (by multiple definitions) can corrupt the potential of our species to participate in living intentionally at the scale of life. The act of speculation will be considered as a mode of attention for accessing the outside, other or more than human world by exploring the activity of birding in relation to the art of Tom Sewell. Speculation will then be augmented by harmony in a discussion of Surfing as a more than human sport demonstrated by it’s connection to Birding as an activity of speculative attention. Surfing experiences will then provide demonstrations of Speculative Realist philosophy and Object Oriented Ontology guided by Steven Shaviro, Eugene Thacker and Timothy Morton in showing how participation with life contradicts human exceptionalism.

The chapter It’s Not The End Of The World will confront my personal difficulty with finding space to write about contemporary art throughout this work. This chapter will assess the place of art in my own life and its role in the wider context of the art world. Interior and exterior modes of thinking and living are questioned in the context of art as life by exploring the work of Marie Angeletti and the philosophical meaning of Roland Barthe’s concept of Studium and Punctum. An argument will be made for art as life as a state of self-contained attention that denies living through its interiority.

The final chapter will go outside by looking at the value of the world outside of art to art itself and how this is echoed by the value of experience and time spent out of doors. This will include a discussion of Emily Strachan’s navigation of employment with a fine art skillset resulting in finding more authenticity for the application of this skillset in the world of gardening rather than the world of art. This will be an examination of how limited funding and a devaluing narrative about the arts is causing artists to retrain and considers the benefits of this skill diversity.

There’s More Than One Way To Clean Your Asshole

I miss Covid-19. Lockdown was the best time of my life. I mean it - no hyperbole. Partying is overrated and busy places overwhelm me. I was a lucky dude. My furlough pay from my employer - warehouse paying minimum wage - was based on my average hours of the previous three months and I had worked 4 – 5 days a week instead of my usual 3-day week for most of that time. My pay to not go to work was more than my usual income, I was just about to become a student again, I was living with my the love of my life and we had almost zero financial obligations.

Does anyone from the UK even remember when the only time outdoors or exercise permitted was one run, walk or cycle a day for one-hour maximum, within five kilometres of where you lived? I do.

My partner, Emily Strachan, and I walked forever, 100% breaking that one-hour time limit rule. We walked slowly, inspired by Hamish Fulton’s Group Walk at Curzon Park, for hours around the ghost town Aberdeen had become. For some reason, a large portion of the population of our city had evacuated and we had both rural and urban areas within our 5km. I recognise our privilege and I know people were suffering. For us though, the pandemic was authentically wonderful.

Fig 1.

Before lockdown, while people were running around in a media-induced panic, buying towers of toilet paper and pasta, we were very scared. It was intimidating to see people flock from out of town to so willingly ransack our local supermarket because theirs were already empty. Their ravenousness eventually inspired our calm. We soon realised that we still had a shower, and that no one was buying the fresh fruit and vegetables. At the risk of sounding crude, we decided that, if it came to it, we did not need toilet paper for survival because there is more than one way to clean your asshole. Water being one of a few glaringly obvious methods, which in Scotland is almost free. Our eating became rich with a variety of nutrition and flavour as we were forced to explore the world of vegetables in more depth than we ever had before. This exposed a gap between the ways that people seem to think things should be, versus the potential for living in radically new ways within the same system.

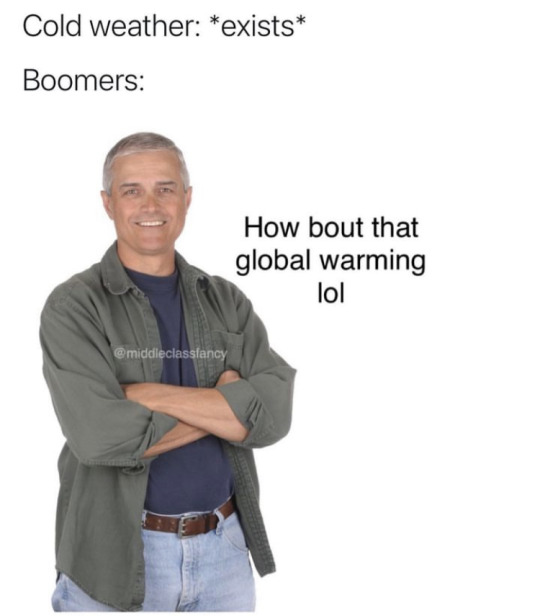

We were questioning what normal is, in an era of narratives hallmarked by: debating the significance of upsettingly high death tolls, the greed of hoarding household provisions and the scary argument that emerged about how vulnerable people should just accept that Covid-19 may kill them rather than continue to cause inconvenience for everyone else as society grew bored of lockdown rules. The choice was between quote-unquote the new normal; a version of normal that favoured selfishness and a lack of accountability for decisions made allowing people to live in denial of how their extremely limited view of life has resulted in a fundamental change in life itself. Or; if it was not the new normal then there was desperate need to get back to normal as if normal was anything close to satisfying. What has getting back to normal got us? War in Europe for the first time this century, more of all that fun climate stuff (fires, floods, storms, extreme temperature variation etc…), global nuclear war is kind of back on the table (yay!) and at home in Britain all that ever so tasty sewerage flows into the waterways and austerity has done so much damage that strikes are once again commonplace. But, you know, actually we had a cold snap in winter, so things will probably be ok maybe actually.

Fig 2.

Emily and I realised that things could be done differently. Between us, a continuing dialogue has developed around ideas of separating ourselves from the mainstream yet narrow view of life being something oriented by the mediating actions of economy (Latour 2020) where the organisation of the world is limited to human perception as being the highest degree of reality (Shaviro 2016). We seek to free our attention from the limits of containment.

Birds Have Better Lives than Humans

Animals have always fascinated me. Birds in particular excite me in an unusually sincere way. During the planning of this piece of writing, it was unthinkable to me that I would include any evidence of my enthusiasm for birding. In a discussion with my tutor about my research for this dissertation Chris Fremantle said something about birds having better lives than humans. This comment resonated with much of my thinking and revealed to me that my interest in birds was a way to make my own research more accessible to myself.

In late 2019 Emily bought me The Hamlyn Guide To Birds of Britain and Europe. Birding was a mostly secret part of my life that I rarely indulged because my other 20-something year old peers were not that interested, often dismissing it mockingly.

Receiving that book, I realised my partner enjoys and actively participates in the same niche cross-section of interests and lifestyle choices as I do. Together: birding, surfing, watching cartoons, eating plant-based, ignoring texts and walking aimlessly, we lead a life that for the most part is dedicated to the immediacy of our tangible surroundings, enchanted by our “ongoing attention to a world that is also attending to us.” (Ingold 2018 pVI)

Today, I am a straight up birder. I love birding so much because it is boring yet substantially engaging. The feeling of gratification after seeing a bird is similar but more comprehensively fulfilling than time spent using online media. The existential dread of online encounters is pushed aside by an encounter with a bird because the bird encounter pulls my attention into the living world rather than out of it whereby instead of being a spectator of life, I become an active participant (Haladyn 2015). Of course, by my use of the word life here I do not necessarily mean exclusively an individual’s own lived experience but a more expansive idea of life as a whole collective system of processes and entities on Earth (Latour 2020).

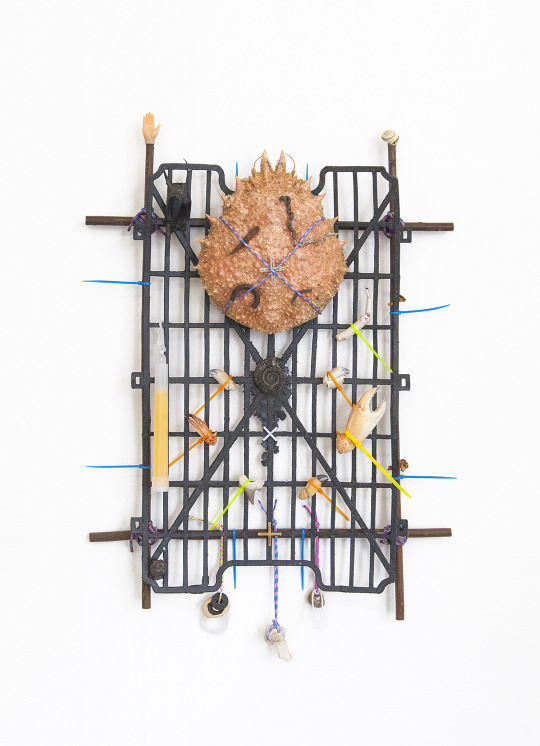

Fig 3.

Slough - Tom Sewell; Mixed media sculpture.

Spider crab shell, plastic, willow, paracord, glow stick, shark’s tooth, ammonite, claws, bone, rubber, shells, mushrooms, iron, mermaid’s purse, flint.

Tom Sewell is a British artist who makes work concerned with active participation of life in recognition of the more-than-human world. Pictured; is a sculpture by Sewell titled Slough. This sculpture is constructed out of materials found during immersive walks in unfamiliar landscapes. The process is about giving attention to the living world and participating in being with it. Slough creates a single structure by unifying human-made objects with living and non-living natural entities. It is through this unification that Slough offers the viewer access into experiences of immersion in the landscape of the tangible realm of the outdoors. Sewell invites speculation around the conflict between the internal human-only world and the external more-than–human world. It is through this act of speculation that the viewer of Slough is able to consider life as something beyond individual experience and question the connectivity between humans and nonhumans (Birt, Shin and Clara 2020).

I believe the origin of many a birder’s love for the activity lies with a similar type of speculation. Much like the walks of Tom Sewell, the act of birding is an intentional attempt to participate - without interfering - in a world that is other than human. In discussing the importance of speculation in relation to realism, Steven Shaviro references what Eugene Thacker “calls the world-without-us” (Shaviro 2016 p67). A human cannot possibly know what it is like to be a bird from a bird’s perspective (Nagel 2016) but nonetheless the ways in which birds live entice the observation and attention of birders to create a phenomenon that resembles a non-dominative approach to interspecies connectivity.

The human birder has a devotional practice of speculative attention, offering time and thought to birdlife by observing, appreciating and attending to a world (Ingold 2018) that is indifferent to these actions (Tamás 2020). The act of speculation here is directing attention into the external “world-without-us” (Thacker 2011 p6) and in doing so; birders are being outside in both that they leave the internal environment of the human-constructed indoors to be outdoors and that they leave the limited, internal human perspective to actively seek and consider other experiences that are different and external to the human-centric “world-for-us” (Thacker 2011 p6). It is by being outside, out-of-doors and exterior to the human only world that birders become realists because of their recognition of a world without them that is only accessible to them through their speculative practice of attention.

Surfing; A More Than Human Sport

In May 2022, an online Stab Magazine article titled “Surfing’s Dark Secret: Birding” was published. This was another moment where two activities I participate in, surfing and birding, harmonised. In the piece, Paul Evans explains that other activities often paired with surfing such as: golf, MMA fighting and fishing are mismatched. The argument is that surfing is an activity where one engages actively but - and this distinction is important – harmoniously with multiple elemental and cosmic processes. Birding is a harmonious engagement with these processes but the other activities are not. These activities are all dominant, oppressive and contradict what surfing actually is through their violence. Indeed, as Evans points out, golf courses are chemical soaked monocultures that dominate landscapes through their denial of space for other human and nonhuman uses of the land. In Britain for example, there is “more land devoted to golf courses than to housing” (Evans 2022). The violence in MMA fighting is juxtaposed with “surfing ohana” (Evans 2022). Ohana is a Hawaiian word that means family; it is a word for addressing those with whom one has compassion. Surfing originated in Hawaii, where the most important surfing events are held today. Hawaiian cultural customs, including ohana, are still valued highly and respected throughout surfing’s now global following, to such an extent that even the best surfer, hoping to succeed in Hawaii, will not get very far without observing ohana. Both MMA fighting and fishing (when not for survival) are not practices of compassion. Finally, Paul Evans points out the absurdity of fishing for sport as a mode of appreciating nature:

“Fishing is a great one for nature lovers, marine wildlife enthusiasts or folk who just adore the great outdoors. You sense a wild creature swimming around free in the sea, perhaps even for decades, and instinctively think: “I’d love to hook you through the face, stove your fucking skull in with a mallet whilst you suffocate, then share pictures of your corpse.”” (Evans 2022).

Surfing, like birding, is a devotional practice that demands participation in the more than human world. It takes a long time to gain skill in the sport and the more experience a surfer gains, the more auxiliary skills are practiced in developing an understanding of the elemental and cosmic processes that feed and shape the surfing experience. Truly skilled surfers seek not to overpower the ocean, knowing that this is impossible; they try instead to flow with it. Surfing is a cosmic action because of the fugitive endeavour of the participants’ seeking of flow with a singular and fleeting pulse of energy. No ocean wave happens the same twice and for this reason surfing is also elemental. The multitude of ecological and environmental factors that create surfing situations ranging from local bathymetry, to global weather systems and further to the impact of the moon phases upon tidal action must be observed, understood and depended upon. This necessarily demands an awareness of interconnectedness and interdependence in an appreciation of uncertainty. It is this premise that causes me to find connections between surfing and speculative aesthetics. I believe surfing to be a practical demonstration of the claim that the philosophical concept of finitude is about more than simply the limits of knowledge. Exemplified by the following quote from The Universe of Things On Speculative Realism by Steven Shaviro:

“Finitude, therefore, means not only that there are limits to our knowledge of the moon but also – and much more importantly – that there are limits to our independence from the moon.” (Shaviro 2016 p137).

This exact example that Steven Shaviro has chosen to use, the unseen – but definitely there – effects of the moon upon which humans depend, happens to be something that is already widely recognised by surfers. The activity of surfing compels surfers not only to consider their knowledge of the moon but also their dependence upon the actions of the moon in itself, which are autonomously separate to any human knowledge of the moon.

Ok, I am sorry. You, presumably an artist, the reader of this essay, have just read several paragraphs by me, some sporty jock and somehow also an artist, about why my sport is better than other sports. Hopefully I have not lost you yet because here is where things get exciting.

When we (artists) think of sports, we tend to think of the objectivity and rigidity within them. The lack of space for the intrinsically weird (Morton 2021) in sports is probably what makes the relationship between artists and the world of sport an uncomfortable one. Surfing however is uncomfortable with the idea of itself as a sport. All that stuff about Hawaii and Ohana and golf being “a bit Trumpy” (Evan 2022) is more important than the ramblings of just some dude that likes to surf.

Surfing originating in Hawaii and being developed by Native Hawaiians means that this particular sport grew out of something completely isolated from the sports that developed out of western or European agricultural and theistic practices. This is because western colonial contact was first made with Hawaii in 1778, which happens to be after the invention of golf for instance. Obviously, surfing has been colonised, westernised and objectified; so extensively in fact that 2020 saw it becoming an Olympic sport. Yet somehow, surfing has not been completely assimilated into western anthropocentric ideals, it still sits somewhere in the margins, shrouded in something more mysterious than sport.

Surfing seeks flow with a more than human entity through nurturing awareness of unintended consequences between the interaction of wind transferring kinetic energy into bodies of water and that same energy interacting with specifically contoured areas of near-shore sea floor shaped favourably but completely coincidentally by deep-time and geological force. This would make surfing an act of ecological awareness in accordance with Object Oriented Ontology because as Timothy Morton (2021 p16) writes; “Ecological awareness is awareness of unintended consequences”. Furthermore, the seeking of harmony with the cosmic and elemental energy of ocean waves, through surfing, is not an exclusively human desire and act. Many animals have been observed surfing. I personally have seen Dolphins surfing the same stretch of beach as me and many surf films and nature documentaries depict not only Dolphins but also Seals and Penguins engaged in the act of surfing for no apparent reason other than fun. Birds of course, are Earth’s most graceful surfers. They ride the air currents produced by an ocean wave meeting the shore and they engage in much the same ballet-esque performance of stylish manoeuvres upon the wave face as humans aim to do (Evans 2022). Surfing may be the only human sport that nonhuman beings participate in through their own autonomous choice to do so, outside the coercion or force of humans. Although humans do unfortunately, force some animals to surf, such as pet dogs.

It is my position that surfing, emerging from something outside of western anthropocentrism as a harmony with elemental and cosmic processes, is a way to relate to nonhuman beings because it comes from and alludes to an alternative to anthropocentric ideals through both its origins and its unintended consequence of purposeless collaboration with something that is more than and other than human. Or, as Timothy Morton (2021 p37) puts it when referring to art, “a glimpse of living less definitively, in a world comprised almost entirely not of ourselves.” It is this window into the “world-without-us” (Thacker 2011 p6) that surfing shares with birding and with art.

It’s Not The End Of The World

I start to question myself when I feel this uncomfortable about mentioning contemporary art despite being a few thousand words deep into an essay about contemporary art. There is a tension in the relationship between art and sports as in philosophy there is tension between the subjective and objective. Certainly, it is exceptional to be a sponsored athlete and an exhibiting artist.

Art has been central for me since birth as a completion of the whole. It has been ingrained in me that art is paramount to a holistic and healthy navigation of my thoughts, emotions and experiences in pursuit of understanding and peace. And yes, I can confirm that it is indeed traumatic knowing this and growing up in a society that almost entirely rejects this. Art has become something that does not need justification for me. It is a completely essential part of my life, but like essential things in life (such as staying hydrated) it exists in a place that also renders art somewhat banal. I think that this primacy of relating everything through art has contradictorily made art hold a secondary place on account of its obviousness. Art is already. It is necessary but it is not valuable, but it does have worth. Art has something Timothy Morton (2021 p54) calls “alreadiness”. This alreadiness is something we are conditioned to deny in the same way that much of life in global-westernised society conditions humans to exist in denial (Zerzan 2012) of Life with a capital L(Watts and Latour 2020).

“Alreadiness hints at our tuning to something else, which is a dance in which that something else is also, already, tuning to us.” (Morton 2021 p54-55).

What Timothy Morton means is that there are certain experiences in life that upset the grossly-utilitarian, survival before living, paradigm that humans have organised themselves into because these experiences do “something to you” (Morton 2021 p67) and I agree with Morton that art is one of these things. The encouraging and optimistic tone that Timothy Morton uses in their subjunctive writing in All Art Is Ecological is something I value deeply about the book however, due to this, it frames art as some kind of insurmountable and singularly special thing. This is where I have points of my own to add to Morton’s.

In his book – with a contrasting and perhaps unnecessarily extreme tone of pessimism – Future Primitive Revisited, John Zerzan (2012) explains that an art practice emerges out of a lack of earnest connection with the more than human, natural world. For Zerzan, art becomes a placeholder for a sincerely fulfilling life as it expresses the need for an absent interconnectedness and a will to disengage with mainstream narratives of what it means to be alive. Indeed, anecdotally I find this to repeat itself as at least partially true in my own experience.

Personally, I find that the established norm for us artists practicing art, particularly in the academic setting, has very little room for embodied lived experience despite any celebration or encouragement of it. Simply put, art practice demands immobility to some extent and time spent in lifeless indoor, interior environments. I must be sitting down to read, sitting to write this essay or – in the future – writing funding applications of similar density. We are always sitting. Sitting in the crit, sitting through a lecture, sitting for a seminar and sitting to invigilate a gallery. Sitting vacantly, looking interiorly. Staring at a computer screen, the white cube gallery empty of character. Staring at artefacts decontextualized by their museum setting (Haladyn 2015) searching everywhere for the absent, highly coveted contexts to serve our own academic needs. We love our little void, the white washed artist studio, with no windows and the air strong with toxic chemicals accented by the dense energy of passionate thought. Of course, we claim that art has a transformative power over these places and actions that can enchant them and I am inclined to agree but all this sitting still and being indoors is excruciating. As my favourite surf coach Cris Mills (2022) will tell you; sitting destroys mobility and posture. Too much dysfunction in those bodily systems will significantly impair the capacity of a person, named Jess Connor, to do something like surfing.

There is an undeniable vacuous toxicity, literally and figuratively, present in the space that art operates in. All this time spent in empty rooms, filling them up with manifestations of traumatic experience may well lead an artist to believe that it is the end of the world, as some of my peers do. Artists, surrounded by artists in arts environments constantly reflecting back to each other that the interior art world is life, questioning the authenticity of life lived outside the production of art. For me there is no boundary to this circle because I can walk into the photography studio at school at almost any time and talk to my father (who is also staff at Gray’s School of Art) about the exact same things I talk to my tutors about except this room has no natural light, must be mechanically ventilated and the relationship is simultaneously nuclear family and student/teacher. How much further inside the interior can it get than that?

This containment brings to mind the Studium and Punctum of Roland Barthes (1988). David Barker (2014) explains that Studium and Punctum are useful in determining if photographs are worth occupying the viewer’s attention. I find that the Studium and Punctum concept transfers well to assess attention in itself. Studium is “a kind of general, enthusiastic commitment” (Barthes 1988 p26) much like the previously stated interiority of art as a mode of living. It is a humdrum and necessary kind of attention. Art as life is a Studium because it exists within the familiar. Punctum is the disruption of the familiar. Art output can be a Punctum by the enchanting and imaginative productions of its attention. Art as life however, posits art as the exclusive input for art production whereby art operates in substitute for the other inputs of being alive. Exclusivity of input produces self-contained attention or a Studium. David Barker (2014) interprets Studium to mean kitsch, defining kitsch as “the categorical denial of shit.” (Barker 2014). Barker refers to the novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera to further develop his definition of kitsch; “Kitsch is a folding screen set up to curtain off death.” (Kundera 2004 p196). This definition of Kitsch is then used to define Punctum as “the element of a photograph that forces us to acknowledge the existence of shit, or (since shit is probably used as a metaphor) the inevitability of death.” (Barker 2014).

It is through Barker’s definition of Punctum as the acknowledgement of death that we can deduce kitsch to mean the denial of death through his explanation that kitsch is the denial of shit and that shit is a metaphor for death. If art as life is an interior reflection of itself operating in substitute of other inputs to produce self-contained attention, it is a denial of the exterior. Life is happening elsewhere (Hannula, Suoranta and Vadén 2005) in an outside realm that is unknowable from the inside. An entity operating exclusively in interior to itself can only produce reflections of itself whereby its self-contained attention only serves to deny life through denial of the exterior. Art as life, or art as a Studium becomes a refusal of life because of its interiority to itself. Art as life cannot die because it is not alive and in this way it raises Kundera’s “folding screen” by seeking to be a way of being that escapes death. It is by this reasoning that I find the concept of art as life to be kitsch. It seems as though that for most artists, art as life is something to be leaned into and celebrated as some sort of quantitative indicator of commitment. For me however, art as life is something I seek to escape because of the echo chamber that causes me uneasiness through its interiority to itself.

Studio days and art events feel much the same as doom scrolling. It has something to do with being stuck indoors, it also has something to do with my ADHD but I think it has a lot to do with it being the net effect of scrollers discussing their scrolling. Not that this is unique to artists because everybody scrolls but the agonistic and speculative interrogation of information exists in few domains outside art. The denial of the outside through embracing the closed-circle of niche interest and algorithmic reification creates a separation between human and world. The human becomes less than human and the world becomes unworldly.

“Doom is humanity given over to unhumanity” (Thacker 2015 p20)

It’s not the end of the world. All this reflection inwards removes the human from the position of a participant of life. The process of interiorisation serves to decontextualize and the human becomes a spectator of life (Haladyn 2015).

An online review written by Sean Tatol for The Manhattan Art Review compares two exhibitions, The Painter’s New Tools at Nahmad Contemporary and Manhattan by Claude Balls Int. that happened over the summer of 2022.

The Painter’s New Tools showed painting, from a list of artists too long to mention, who did not use exclusively paint but used instead some variation of digital assistance to create paintings. The press release for the show makes bold claims that Sean Tatol argues the show does not meet at all. Claims such as:

“Now is the moment for art that expresses how it feels to be alive now” (Cayre and Kissick 2022)

“We want to show painting that is vital and of the moment.” (Cayre and Kissick 2022)

There are clues in the hyperbolic syntax and the repetitious assertion of newness. Tatol (2022) explains that the show achieved the opposite of the quoted aims precisely because of its use of digital media framed as something new. His key points being that while the technology that the digital field offers is recent, collaboration with it in contemporary art is already dated by a decade. Digital images are so prevalent in life at this moment but the work in the show fails to do anything to sincerely address this and serves instead only to offer reflections or extensions of the alienation of our digital lives in 2022. The show erroneously commits to a gratuitous faith in the idea of technological progress being equal to progress for the lived experiences of human and nonhuman life on Earth in a way that completely denies how unsatisfactory things actually are (Tatol 2022).

“To be sure, you couldn't physically make most of the work without modern technology, so it is literally contemporary, but that doesn't guarantee a new expression of life in 2022.” (Tatol 2022)

“Moreover, this belief in the present is now dated, ironically, because such an attitude has been untenable for nearly a decade and just comes off ridiculous in the face of our manifest reality. Positing the newness of new tools is little more than burying one's head in the sand, a naive willingness to believe in exactly what will never save anyone.” (Tatol 2022)

What Sean Tatol writes of Manhattan is much more encouraging. The ephemeral art works made using old tools were installed at night and shown in a courtyard where Marie Angeletti, one of the exhibiting artists, lived. Sean Tatol praises the work in Manhattan as definitively contemporary, not because of new tools but the new ideas the show has to offer. Much of the show was comprised of found materials and Marie Angeletti’s piece was a pile of broken glass and asphalt displayed under a spotlight that exhibition visitors were allowed to walk on and touch.

Fig 4.

The work put together by Marie Angeletti here shows a willingness to disengage with the production of spectacular but safe artworks that serve to please the conservative tastes of the financial elite (Tatol 2022). She chooses instead to engage with the tangible and immediate surroundings of Manhattan to create work that participates in life through her actions in collecting the materials for the piece. The work then maintains its tangibility through its tactility and lack of collaboration with any new or novel technology. The piece indicates a series of real world interactions between Angeletti and the people and structures of the surrounding Manhattan area in realising the work that the viewer can access through speculation upon the work’s scale and ephemerality (Tatol 2022).

“The realm of virtual fantasies has proved itself to be a hollow simulacrum, and tangible reality has therefore turned back into a new space.” (Tatol 2022).

I find the discordance revealed by Sean Tatol in the comparison of these two exhibitions to be compelling evidence of how art can be used to either look beyond by going outside of what is known or to remain inside of itself and familiar. The Painter’s New Tools straddles the familiar and the interior. It celebrates the interiority of digital media as an exclusivity of input for human thinking and progress by an output that duplicates the already known, human only realm of the digital. The work (output) is stuck in repetition of its input, forcing all momentum of thought into the inside where it can only move further inward. The work assumes the position of art as life through the presentation of its human exceptionalism and therefore becomes kitsch in its denial of life. The Painter’s New Tools is thereby Studium and doom by means of its unhumanity.

The artworks in Manhattan go beyond the interiority of the human and digital to go outside with the world by seeking inputs that are external to art from a life that includes within its scope much more than human survival. Its lack of aesthetic prettiness allows it to operate outside of commercialism (Tatol 2022) by bringing forward “how empty everything we're given to fill our emptiness is.”(Tatol 2022). The work of Marie Angeletti in Manhattan is an example of uncontained attention because it broadens the scope of input by its generation occurring outside, out of doors and in recognition of the external. This break in the eternal interiorisation of art and life becomes an allowance of being alive by producing external outputs through a diversity of input.

Get Out

The world is still there. Out there. I find it too easy to forget. It is also easy to be convinced by others that one should not be out there. When humans cannot go outside of themselves, outside of what is known and into the indifferent space that is other than human and out of doors, it places a restriction upon the scope and sufficiency of thought which becomes sour and decrepit (Tamás 2020).

Emily Strachan (aforementioned bird-book-gifter) is someone who had to get out. A graduate of Contemporary Art Practice at Gray’s School of Art, Emily is a relentless creative maker and a lover of tactility. The way that post-graduate life is set up in regards to art-job-seeking however, is discouraging because the long applications for short-term work are tedious and often the work is much less than what the artist aspires to. For example, as a result of organisations such as Arts Council England increasingly demanding, as a pre-requisite to funding, a perceived benefit to the public (Jones 2020) many paid roles for graduates or emerging artists are often more aligned with teaching, social or care-work. In her research paper The Chance To Dream: Why Fund Individual Artists? Susan Jones (2020) uncovers that there has been a steady trend, since 2003, of declining investment in “no-strings” (Jones 2020 p3) attached funding for artists. The imposing of limitations upon the working methods of artists through funding limits the potential for the production of challenging and rigorous fine art by targeting and undermining the value of the artists work both in itself and within society (Jones 2020). This forces adaptability and enthusiasm that introverted artists, such as Emily and I, often tend not to have. My ability to produce art and my enthusiasm for making has very little or no cross over to helping an after school club make decorations for a Christmas parade. This is something I have been paid to do by an arts organisation in Aberdeen.

So for Emily, freshly graduated and met with the joy of a pandemic, the scope of things looked bleak. Weeks or even months of work go into applications for jobs that only last equally as long. Enthusiasm is expected for the work as if it is the dream of life to be indoors postulating on world improvement with other artists or being a child-minder with a capital ART somewhere in the job title or description. The art world insists an artist is soooooooo lucky to be graced with any such paid opportunity despite that if one were to remove the word “art” from the description, the job would suddenly start to look a lot like something else and much less glamorous. My point being, an art job needs to involve art and not be glamourized by (limited) association to art. Art, discordantly with its own values, follows the rules of commercialism by subscribing to glamour and in doing so objectifies itself (Tatol 2022). It is as if the art world does not believe that art is necessary. Art is in survival mode. Perhaps that is understandable, if the rest of the world is also in survival mode in an era of mass extinction (Morton 2021). Maybe the world in itself does not need to be improved and maybe artists are not saviours? As I have said, the world actually still is out there and out there feels pretty good. Perhaps it is the role of the artist to be out there to show us that there is a world of life to become immersed in (Ingold 2018).

In the end, the art world’s interiority was too disappointing for Emily and she began to look outside for work. In 2021 Emily became a National Trust for Scotland Apprentice Gardner. One of the key determining factors for Emily getting the role, which was one of only two positions available in the region, was her First Class Honours Degree in Contemporary Art Practice because of the skillset it represents. The success of Emily’s interview guaranteed her paid work, all week, every week for the next 2 years. This exposes something tragic about art. The horticulture industry values Emily’s arts-based skillset enough to pay her for her time in an entry-level position with a job title and training included. The same skillset and qualification is so under-valued by arts organisations that it is often not worth a penny or a job title as volunteer positions at the entry-level prevail in the arts industry.

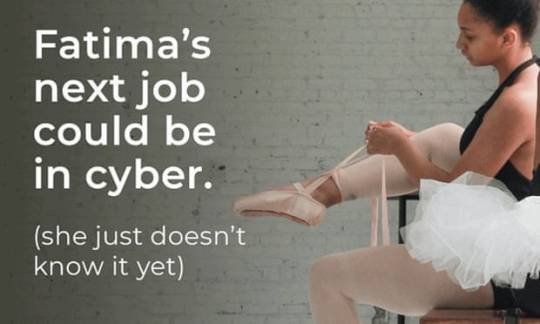

Perhaps it would be to shoot myself in the foot not to consider that the National Trust for Scotland is likely the recipient of a larger wealth of funding than any arts organisation I should choose to criticise. Should organisations receive more funding, it might result in more paid opportunities for graduates. Indeed, funding for the arts has been systematically slashed (Jones 2020) and the fine work of the UK’s Conservative government sees public opinion swayed by a drip feed of rhetoric that consistently undermines the value of art by positing it as a career not even worth pursuing. Rishi Sunak, Britain’s third Conservative Prime Minister of 2022, suggested in 2020 that artists and musicians should retrain (Burgess 2020) amid a backlash against a poster backed by the government depicting a ballet dancer named Fatima with text saying she should retrain in ‘Cyber’ (Bakare 2020). As Tim Burgess (2020) wrote for the Guardian, a career in the arts is treated by the government as a “luxurious, decadent hobby” despite the arts sector generating billions in revenue (Burgess 2020) for the UK economy.

Fig. 5

In any case, the devaluation of art by the British government, reflected by the state of funding, seems to be working. Emily is retraining in horticulture. Fortunately for Emily, it seems to have put her in touch with something more authentically connected to what she was trying to express in her productions of multi-sensory sculpture. Much of her artwork is concerned with seeking a fulfilling sensory engagement with ecology but worked with ecologically harmful materials such as resin and silicon. Perhaps now that she is involved with the production of plant life in the multi-sensory garden of Crathes Castle, she is experiencing a necessary and true evolution in her relationship with ecology and all of her senses. For me however, things look pretty gross. The demands of maintaining a career in the arts within the current state of governmental deterrence (Bakare 2020) and defunding (Jones 2020) do not appeal to me. Will I achieve my Honours in Contemporary Art Practice only to move on and retrain? It remains to be seen. Certainly, it is often that shifts at the warehouse paying minimum wage are preferential to any time spent hustling, networking or filling out applications for work opportunities. All of these activities could be grouped under a singular heading; having to work while I am not at work (Southwood 2011). I should not have to feel pig-headed when I assert that I am somewhat unwilling to compromise my creative practice to meet the needs of funding bodies that seek to put limitations (Jones 2020) upon the scope of my artistic output.

Conclusion

“To exist is to be sensing continuously, consciously or not, our senses are at the forefront of it all and they build our perception of the world.” (Strachan 2019 p22)

In this piece of writing, I wanted to explore how engagement with the wider more than human world, that is external to the realm of human only knowledge and experience, can challenge the human idea that humans are exceptional in their being. To do so, it was crucial to distinguish the difference between internal and external engagement with life. Reframing human-dominant ideology with a more speculative and co-operative approach to the nonhuman is a narrative that opposes the current mainstream position that humans are the stewards of planet Earth. In the questioning of the human world’s interior containment within itself, the importance of how and where humans utilise their capacity for attention becomes imperative to understanding how humans can participate with life exterior to the operations of humanity.

The Covid-19 pandemic and its lockdown of society provided a break in the onward trajectory of human-centric progress to initiate some ideas pertinent to this dissertation. Firstly, that not all bad things are all bad, all of the time. Things are muddy and never this, or that (Morton 2021). In the case of this essay, the bad thing (Covid-19) became a good thing (Lockdown) for the writer (me) because it provided the opportunity to live more vitally and test new ways of living. In it’s horror, it threw the whole of humanity into a more immediate way of being by halting the globalised capitalist economy (Latour 2020). The second idea initiated was that the internal human only world and the external more than human world are not separate. We see this in how a nonhuman being, an unfriendly virus named SARS-coV-2 (Covid-19), forced the world into an emergency position of economic shutdown with the unintended consequence of giving me a better life than I already had, temporarily allowing me to escape the drudgery of employment (Zerzan 2012) to engage in a more fulfilling life oriented around immersive experiences out of doors. In other words, a nonhuman being changed my life and did not grant me agency or control as to how the change emerged.

At some point during this contemporary art essay about birding and surfing you may have noticed that I actually did mention some art. When I think about how urgently I feel I need to be presently participating with life in the context of art, I find myself questioning the value of art as a useful form ecological awareness in its current state of underfunding and grandiose spectacle. Recently, I have been painting a lot and I have been selling those paintings. I was consequently told that my creation of art as a commodity object is in conflict with my research around speculation, ecology and nonhumans. I agree, but painting is so easy and money is so useful. I am scared to take the risk of being more rigorous with my work. The realisation is that any art that actually is challenging, exciting and genuinely addresses ideas of ecology to me – such as the work of Tom Sewell and Marie Angeletti – is art that does not look like art to many people in my life who are outsiders to the internal world of art. This is why I look to activities like walking, birding, surfing and gardening as valuable operations of a fine arts skillset, because they all present ways of being a participant of life in a way that utilises all of the senses. When I paint, I find my own work to be a disingenuous realisation of the research presented in this essay because it isolates my thinking from embodiment. When I surf however, I am in a synthesis of thought and embodiment and I am “sensing continuously” (Strachan 2019 p22). In the sea I am literally in somethingthat is more than me and more than any other human, I can touch it, I can taste it, I can smell it, I can hear it and I can see it. I have yet to find this kind of vital, multi-sensory participation of being alive in art. I believe I might not be looking hard enough but the point remains that I cannot find something in art that better fulfils speculative engagement with the nonhuman world than active encounters such as birding or surfing.

The main way contemporary art does seem to be able to earnestly engage with this is in the ways that Tom Sewell and Marie Angeletti do. By collecting things from the tangible world and displaying them as art artefacts as a means of slowing down and looking somewhere that is not a screen with internet access. Yet despite finding value and enjoyment in this form of artwork, something in me feels like this is not enough. It does not have the same vitality as surfing and birding and I am scared that this lack of vitality in some way disconnects this kind of art from the initial immersive experiences that bring it into being.

I need to challenge human exceptionalism because humans scare me more than anything else. If humans are the cause of mass extinction then I need to be a part of something else. When I go outdoors and step outside the human world to see the rest of the world, something happens that puts me at ease. This research is about trying to find that within my arts skillset and the acknowledgement that maybe art needs to look like something other than what art is expected to be before I can find it. Perhaps what Emily Strachan finds in the non-productive garden of Crathes Castle to stimulate a multi-sensory fulfilment of interspecies connectivity is the same as what I find in my own non-productive playful engagements with birds through birding and holistic disengagement with the terrestrial realm through surfing. I want to know what this is within art, but I have reached the end of this essay and I cannot conclusively or definitively confirm that I have found it.

Birding, as a form of immersive experience that encourages interspecies connectivity through its speculative engagement with the lives of nonhuman beings, and the artwork of Tom Sewell reveal that there is scope to participate submissively with the more than human world through giving attention to the “world-without-us” (Thacker 2011 p6). We see this exemplified in sport through Surfing in its similarity to Birding. The harmony of surfing and birding, when compared with other activities, suggest that these activities are unique in the way that they place the human as a participant of life without attempting to dominate the other than human realm. This is related to the world of contemporary art because art, unlike surfing or birding, sways toward the denial of life outside of art. The value held by the art world of art is life subscribes to the glamour culture of the mainstream commercial world by refusing the input of the external and remaining internal to itself resulting in contained attention.

I see a growing emergence in contemporary art to embrace inputs exterior to art in the movement towards making work that opposes the commodification of attention by adopting a quiet, somewhat mundane aesthetic to produce artworks that deny commercial glamour and constant distraction by spectacle. This movement in art towards the exterior more than human world, out of doors and external to the known world of humanity, shows us that the internalisation of life has excluded a diversity of input for humans and artists. Operation exclusively in the interior denies life itself through its containment of attention. In a mass extinction age, a speculative approach to the external more than human world could reframe the position of the human from spectator of life to participant of life, whereby immersive experience could create affirmations of life.

Reference List

BAKARE, L., 2020. Minister Distances Himself from Ballet Dancer Reskilling Ad. The Guardian, 12 Oct [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/oct/12/ballet-dancer-could-reskill-with-job-in-cyber-security-suggests-uk-government-ad [Accessed 16 Dec 2022].

BARKER, D., 2014. Barthes’ Studium and Punctum | Nouspique. [online]. Nouspique.com. Available from: https://nouspique.com/barthes-studium-and-punctum/ [Accessed 31 Oct 2022].

BARTHES, R., 1988. Camera Lucida : Reflections on Photography. New York: The Noonday Press.

BIRT, V., SHIN, S. and CLARA, N., 2020. Well Projects on Instagram: ‘A Talk with Verity Birt, Sarah Shin and Nicolette Clara Iles. Discussing Verity’s New Film “Crossings” and Verity & Nicollette’s Long Distance Collaboration and Shared research’. [online]. Instagram. Well Projects. Available from: https://www.instagram.com/reel/CGYHpTml6oZ/ [Accessed 14 Oct 2022].

BURGESS, T., 2020. The Arts aren’t a Luxurious hobby, Rishi Sunak. They’re a Lifeline for Millions. [online]. the Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/08/the-arts-rishi-sunak-job-chancellor-hope [Accessed 16 Dec 2022].

CAYRE, E. and KISSICK, D., 2022. The Painter’s New Tools - Organized by Eleanor Cayre and Dean Kissick - Exhibitions - Nahmad Contemporary. [online]. www.nahmadcontemporary.com. Available from: https://www.nahmadcontemporary.com/exhibitions/the-painters-new-tools#slide:0 [Accessed 26 Oct 2022].

EVANS, P., 2022. Surfing’s Dark Secret: Birding. [online]. Stab Mag. Available from: https://stabmag.com/features/surfings-dark-secret-birding/ [Accessed 18 Oct 2022].

HALADYN, J.J., 2015. Boredom and Art : Passions of the Will to Boredom. Winchester: Zero Books.

HANNULA, M., SUORANTA, J. and VADÉN, T., 2005. Artistic research: theories, Methods and Practices. Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki Academy of Fine Arts.

INGOLD, T., 2018. Anthropology between Art and Science: an Essay on the Meaning of Research | FIELD. [online]. Field Journal. Field. Available from: https://field-journal.com/issue-11/anthropology-between-art-and-science-an-essay-on-the-meaning-of-research [Accessed 10 Oct 2022].

JONES, S., 2020. The Chance to Dream: Why Fund Individual Artists? A-N. A-N the Artists Information Company. Available from: https://static.a-n.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Research-papers-The-chance-to-dream-why-fund-individual-artists.pdf [Accessed 8 Dec 2022].

KUNDERA, M., 2004. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. London: Faber and Faber.

LATOUR, B., 2020. What Protective Measures Can You Think of so We don’t Go Back to the pre-crisis Production model? 1. [online]. Bruno Latour. AOC. Available from: http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/downloads/P-202-AOC-ENGLISH_1.pdf [Accessed 14 Oct 2022].

MILLS, C., 2022. Mobility Drills for More Fluid Surfing. [online]. Surf Strength Coach. Available from: https://surfstrengthcoach.com/mobility-drills-for-more-fluid-surfing/ [Accessed 31 Oct 2022].

MORTON, T., 2021. All Art Is Ecological. S.L.: Penguin Books.

NAGEL, T., 2016. What Is It like to Be a Bat? Stuttgart: Reclam Universal-Bibliothek.

SHAVIRO, S., 2016. The Universe of Things: on Speculative Realism (Posthumanities). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

SOUTHWOOD, I., 2011. Non-stop Inertia. Winchester: Zero Books.

STRACHAN, E., 2019. Are We Living in a State of Hyperaesthesia or Sensory Deprivation. Undergraduate Dissertation.

TAMÁS, R., 2020. Strangers : Essays on the Human and Nonhuman. London: Makina Books.

TATOL, S., 2022. The Painter’s New Tools & Manhattan. [online]. 19933.biz. Available from: http://19933.biz/newtoolsmanhattan.html [Accessed 14 Oct 2022].

THACKER, E., 2011. In the Dust of This Planet. Winchester: Zero Books.

THACKER, E., 2016. Cosmic Pessimism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

WATTS, J. and LATOUR, B., 2020. Bruno Latour: ‘This Is a Global Catastrophe That Has Come from within’. The Guardian, 6 Jun [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/06/bruno-latour-coronavirus-gaia-hypothesis-climate-crisis [Accessed 10 Oct 2022].

ZERZAN, J., 2012. Future Primitive Revisited. Port Townsend, WA: Feral House.

List Of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Screenshot from YouTube video of Hamish Fulton’s group walk at Curzon Park. GALLERY, I. and FULTON, H., 2012. Hamish Fulton Group Walk, Birmingham. [online]. www.youtube.com. Ikon Gallery. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2XaX4ktvQ_0 [Accessed 10 Oct 2022].

Fig. 2 IMAGE: MIDDLE CLASS FANCY, 2022. Middle Class Fancy on Instagram: ‘Haha I know right? It’s winter and it’s cold out? What’s all that about lol’. [online]. Instagram. Middle Class Fancy. Available from: https://www.instagram.com/p/CmjoQvbOgdt/ [Accessed 25 Dec 2022].

Fig. 3 IMAGE: Tom Sewell. SEWELL, T., 2021. Slough ��� Tom Sewell. [online]. Tom Sewell. Available from: http://www.tomsewell.co.uk/work/slough/ [Accessed 14 Oct 2022].

Fig. 4 IMAGE: Claude Balls Int. 2022. Manhattan Install Views – Claude Balls Int, 2022. [online]. Claude Balls Int. Available from: http://claudeballsint.com/?exhibition=manhattan-install-views [Accessed 2 Nov 2022].

Fig. 5 IMAGE: HM Government. BAKARE, L., 2020. Minister Distances Himself from Ballet Dancer Reskilling Ad. The Guardian, 12 Oct [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/oct/12/ballet-dancer-could-reskill-with-job-in-cyber-security-suggests-uk-government-ad [Accessed 16 Dec 2022].

0 notes

Photo

Marie Angeletti

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie Angeletti at Édouard Montassut

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie Angeletti and Bedros Yeretzian at Commercial Street, Los Angeles (September 1-29, 2018)

1 note

·

View note

Link

This week’s featured exhibitions:

Silke Otto-Knapp at Galerie Buchholz

Solange Pessoa at Mendes Wood DM

Ben Echeverria at Parapet Real Humans

Isabella Ducrot at Mezzanin

Marie Angeletti at Carlos/Ishikawa

Marie Laurencin at Galerie Buchholz

Michael E. Smith at Andrew Kreps

Līva Rutmane at Kim?

Sally Späth, Hanna Hur at u’s

Kayode Ojo at Praz-Delavallade

Willa Nasatir at Chapter NY

Gerasimos Floratos at Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Barbara Kasten at Hannah Hoffman hosted by Kristina Kite

Rodney McMillian at Petzel

Jenna Bliss at FELIX GAUDLITZ

Barbara Bloom at Capitain Petzel

Sofu Teshigahara at Nonaka Hill

Jan Dibbets at Konrad Fischer

Nick Mauss at 303

Özgür Kar at Édouard Montassut

Have an excellent week.

Contemporary Art Daily is produced by Contemporary Art Group, a not-for-profit organization. We rely on our audience to help fund the publication of exhibitions that show up in this RSS feed. Please consider supporting us by making a donation today.

from Contemporary Art Daily https://bit.ly/2WO4UoZ

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie Angeletti | Installation view, Les Veaux, les agneaux, Beach Office, Berlin, 2017

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

ram spin cram by Marie Angeletti

source: collectionarchive.tumblr.com

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

O processo de Oh: lições aprendidas em conversa com Sandra Oh

Fonte -- Por Cory Angeletti-Szasz -- 03 de dezembro de 2014

Seja o mais poroso possível. Alimente sua ambição. Aproveite todas as oportunidades que surgirem no seu caminho. Surfe na onda. Trabalhe duro. Acenda sua imaginação.

É assim que Sandra Oh, a ambiciosa e inspiradora atriz coreano-canadense, descreve a abordagem que adota para sua carreira de atriz, a que ela se refere como seu "processo". Oh compartilhou a visão de seu processo de atuação com uma sala cheia de atores, cineastas e entusiastas de sua carreira no Canadian Film Centre (CFC) no sábado, 22 de novembro de 2014, quando visitou o campus para conduziu uma masterclass com o Conservatório de Atores.

O que mais fica claro depois de ouvi-la falar abertamente sobre sua carreira de atriz é que, quando fala sobre atuação, as palavras saem de seu coração e são alimentadas pela profunda paixão que ela tem por seu ofício.

Oh é uma premiada atriz com experiência em teatro, televisão e cinema, e recentemente assinou contrato para produzir seu primeiro longa de animação, Window Horses, depois de ser abordada para colaborar no projeto por sua amiga de longa data e diretora do filme, Ann Marie Fleming. Window Horses é uma história animada sobre Rosie Ming (dublada por Oh), uma jovem poeta canadense que é convidada para um festival de poesia no Irã e descobre a verdade sobre seu pai.

Quando a aula principal começa, uma cena de Window Horses é exibida em uma tela atrás de Oh e da moderadora Kristen Thomson, colega e querida amiga de Oh desde que se conheceram na Escola Nacional de Teatro do Canadá (NTS). A imagem contém uma citação que diz: “Além das idéias de erro e retidão, há um campo. Encontro você lá.” do poeta persa do século XIII, Rumi.

Oh expressa sua satisfação pelo fato de a citação aparecer na tela e por sua representação e interpretação de onde ela está em sua vida - sendo o mais aberta possível a novas experiências e oportunidades neste momento de sua carreira. Essa abertura se reflete em seu envolvimento e apoio à Window Horses. Ela explica que a história é baseada em uma personagem pró-menina e pró-arte, Rosie Ming, com quem ela se relaciona profundamente em sua jornada de autodescoberta pela arte, e que está emocionada por fazer parte desse projeto, acrescentando-a à sua longa lista de realizações e créditos, que incluem interpretar a Dra. Cristina Yang por dez temporadas de Grey's Anatomy, sete temporadas como Rita Wu na comédia de meia hora da HBC Arli$$, estrelar em Sideways, Sob o Sol da Toscana, Last Night, Double Happiness e, mais recentemente, no palco de Death and the Maiden. A lista continua.

Oh conseguiu seu primeiro trabalho profissional como atriz aos 15 anos, em um vídeo de propaganda para a televisão, e não parou de atuar desde então. Após o colegial, ela estudou na NTS e falou de tudo o que aprendeu durante seu tempo lá, enfatizando a importância de continuar aprendendo em sua vida diária.

Nascida em Nepean, Ontário, e atualmente residindo em Los Angeles, Oh faz parte de um coletivo de atores, escritores e músicos. Ela diz que encontra uma fonte inesgotável de criatividade por meio desse coletivo e aprende novas maneiras de se conectar como artista e criadora, e relaciona fazer parte do coletivo à psicologia junguiana: "trata-se de acessar o lugar inacreditavelmente ilimitado da criatividade no inconsciente". Sua fala era cheia de sabedoria e conselhos com as lições que aprendeu ao longo de seus 28 anos de atuação, deixando o público cativado por suas histórias e honrado por obter algumas dicas sobre seu conhecimento e experiência no setor.

Um dos melhores conselhos de Oh foi para que os atores "honrassem o processo". Ela acredita que todos os atores e criadores têm processos criativos únicos, de onde eles extraem sua força e inspiração, e sugere que o processo de todos seja legítimo e necessário: "Nem todos os atores são iguais. Nem todos os atores têm o mesmo objetivo. Nem todos os artistas têm o mesmo processo. E isso pode ser desafiador... respeite o processo das pessoas", disse. Quando se trata do relacionamento dos atores com os diretores, Oh partilha que, sob seu ponto de vista, a responsabilidade de um diretor é criar um sentimento de segurança no set -- um espaço onde os atores podem se sentir à vontade para interpretar. “Ser diretor é como ser um psicólogo brilhante. Cada ator que você conhece e com quem trabalha é completamente diferente. Portanto, precisa ser sensível e aberto a esse processo [criativo].”

Oh também enfatizou a importância de construir e manter relacionamentos de longo prazo no setor. Sugeriu que lugares como o CFC são inestimáveis para formar elos que durarão a vida inteira e quão crucial é ter um sistema de apoio, uma rede em que atores e criadores possam colaborar entre si.

Depois de uma conversa perspicaz e honesta com Oh sobre sua jornada como artista e criadora, os membros da platéia se sentiram inspirados, apreciando e compreendendo mais profundamente seu processo criativo e a importância de se honrar como ator.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Check out Marie Angeletti, TLYA 18_Instant magique/ TLYA 19_Piano/ TLYA 20_Palais des Papes (2014), From Saatchi Collection Benefit Auction

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Chiudi gli occhi, ascolta questo rumore. Ascolta il ticchettio, costante, incessante, della pioggia che scende giù. Della pioggia che batte. Riesci a sentirlo? Riesci a sentire questo silenzio? Chiudi gli occhi, amore, e lasciati cullare dalla vita. Lo fa così raramente, la vita. Così raramente ti culla, che è bello godersi i pochi momenti nei quali ti coccola nel suo abbraccio. Come quando eri una bambina: lasciati proteggere, rimani al sicuro dietro il muro del buio e del silenzio. Così poche volte può accadere. Così poche volte. Può accadere... Chiudi gli occhi, amore mio, non pensare a niente. A che serve esser tristi? C’è già il cielo intero che piange; Tu puoi smettere di farlo... Chiudi gli occhi, amore mio grande, e corri lontano. Vola con la fantasia dispiegati sulle ali dell’immaginazione, prendi quota e innalzati sopra i mari, sfiora le nuvole con le dita, dissetati di sogni, abbraccia l’universo... Chiudi gli occhi, amore mio immenso, chiudi gli occhi! Rincorri con disperazione la tua felicità! Fermati solo quando l’avrai afferrata, non farla fuggire a nessun costo. Prendila e falla tua per sempre. Se riesci a raggiungerla... Ma non illuderti: non è facile. Chiudi gli occhi, amore mio, chiudi gli occhi... E innamorati un’altra volta dell’amore, Amore...

Alessio Angeletti

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie Angeletti at Kölnischer Kunstverein

http://dlvr.it/SpNn2Q

0 notes