#Los Alamos | Birthplace | Atomic Bomb

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The site in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where Robert J. Oppenheimer and his team developed the First Atomic Device in the 1940s is now a United States National Historic Park. It includes structures like this replica of the campus’s main gate. Photograph By Brian Snyder, Reuters/Redux

Trace Oppenheimer’s Footsteps, From New Mexico To The Caribbean

The Father of the Atomic Bomb Chased History—and Then Ran From It. Here’s How to Visit Places Important to the Influential Physicist, Including a U.S. Virgin Islands Beach.

— By Bill Newcott | March 06, 2024

As Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer reintroduces the “father of the atomic bomb” to audiences, there’s no better time to hit the road and retrace some of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s most momentous steps—from New Mexico, where the physicist’s dream of a nuclear weapon was realized in the Manhattan Project; to a Nevada testing ground, where his worst fears about the bomb were demonstrated; to a remote Caribbean beach where he could, at last, quiet the demons that haunted him.

Los Alamos: Birthplace of The Atomic Bomb

The Gadget, as the first atomic device was called by its creators, was born not at Trinity—the New Mexico desert site where it was detonated—but about a hundred miles north, in the sleepy mountain town of Los Alamos. It was there that Oppenheimer, who’d spent some of his teen years in New Mexico, commandeered a former boys’ school as his base of operations.

Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project campus, now a national historic park, is virtually unchanged from his time.

Strolling along the tree-shaded “Bathtub Row”—so named because these were the few houses on campus equipped with full baths—I walk past the squat bungalow Oppenheimer shared with his wife, Kitty, and their two children. At one end of the street, I nearly brush shoulders with a pair of life-size bronze statues: Oppenheimer—resplendent in his famous wide-brimmed hat—consulting with the project’s military head, General Leslie Groves.

Beyond them I push open the door to Fuller Lodge—the former school assembly hall, now an art gallery and community center—and I am transported into the most riveting moment from the film Oppenheimer.

You remember it: Following the bombing of Hiroshima, the scientist stands before a stone fireplace in this room and gives a victory speech to the Los Alamos staff. But even as he mouths words of triumph, Oppenheimer privately suffers searing visions of the devastation the bomb has caused.

And now, here I am, standing before that same fireplace, facing the long expanse of the room’s ponderosa pine walls and timbered ceiling. It is not hard to imagine Oppenheimer at this spot, in awe of what his team had accomplished in three short years; horrified by its implications for the rest of human history.

Trinity: Site of The First Atomic Blast

Most of the year, Trinity, the site of the first atomic blast, is still an active tract of the White Sands Missile Range, in New Mexico. On two special days, however—usually the first Saturday in April and the third Saturday in October—the U.S. Army hosts a Trinity Open House. (Due to what the U.S. Army called “unforeseen circumstances,” the 2024 April Open House has been canceled).

On those days, vehicles with plates from Alaska to Florida line up at the White Sands Stallion Gate, then bounce the 17 miles south to the circular chain link fence that encloses the spot where Oppenheimer’s Gadget ushered in the atomic age. They park in a seldom used lot and enter through a narrow gate, approaching the stark, black monument at the circle’s center with almost visceral solemnity.

Even in spring, it’s kind of hot here in the treeless, open-air oven the Spanish conquistadors called Jornada del Muerto (Journey of the Dead Man)—but not as hot as it got at precisely 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, when a fireball half as hot as the surface of the sun scorched the earth of this basin.

Tourists at the White Sands Missile Range, in New Mexico, check out an example of the “Fat Man” bomb casing, built to contain a nuclear device. Here at the remote Trinity site on July 16, 1945, the Manhattan Project successfully detonated the first atomic bomb. Photograph By Martin Specht, Agentur Focus/Redux

The 100-foot tower on which the Gadget was mounted is gone, but the Trinity crater remains: a broad, surprisingly shallow, plate-like depression. At its greatest depth the hole that Trinity punched into the desert floor measures only about 10 feet. The 100-foot cushion of air under the tower prevented deeper excavation.

“As a reminder,” a guide tells a clutch of tourists, “you are not permitted to remove anything from the ground.”

“Anything” would be samples of trinitite, the glass-like element that was created in the bomb’s searing blast.

Trinity is the main attraction on visitor days, but the curious can hop a bus to a small cabin, the old Schmidt Homestead, about two miles from Ground Zero. It was here, in the former dining room, where Oppenheimer supervised the final assembly of the Gadget.

With its bare walls and polished floors, the empty house looks as benign as a fixer-upper awaiting a redo by a resourceful real estate agent. But it’s not hard to imagine the team of scientists, just days before the blast, gingerly piecing together the Gadget: A sphere of 32 little bombs surrounding a softball-sized ball of plutonium.

All 32 bombs would be ignited simultaneously. And then, literally, all hell would break loose.

Nevada Test Site

After the war, the U.S. government continued to test nuclear devices of ever more harrowing capability—first in the Pacific, and then at the Nevada Test Site, about a hundred miles north of the then backwater gambling town of Las Vegas. (On the 26th floor of Binion’s Gambling Hall in downtown Vegas, you can still dine in the restaurant where tourists once watched their “Atomic Cocktails” slosh back and forth as nuclear tests made the building sway.)

There is no indication that Oppenheimer ever set foot on the Nevada test site, where more than a thousand descendants of the Gadget were detonated over a span of three decades. Still, the site is essential to Oppenheimer’s story in that it represents his worst nuclear nightmares.

“If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world…then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima,” he declared in 1945.

A hundred miles North of Las Vegas, the Nevada Test Site is where the U.S. and Britain continued to test Nuclear Devices after World War II. The site is open once a month for a free tour. Photograph By Karen Kasmauski, National Geographic Image Collection

“Basically, Oppenheimer was against nuclear testing post-Manhattan Project,” says Joseph Kent, deputy director and curator of the Atomic Museum in Las Vegas. “He felt the Manhattan Project was necessary, but when they started working on the hydrogen bomb, which was much more destructive, he wasn’t comfortable with that.”

We’re standing in the lobby of the museum, now in its 25th year, just a few blocks from the excess of the Las Vegas Strip. Near the door rests an enormous, bulbous “Fat Man” bomb casing, built in 1945 to contain a nuclear device like the Gadget I saw in New Mexico.

Primarily, the Smithsonian-affiliated Atomic Museum serves as a visitors center for the Nevada Test Site, officially known as Nevada National Security Sites (NNSS). Thanks to the museum’s continuing relationship with NNSS, once a month a busload of 50 or so history buffs leave from the museum’s parking lot to begin a free eight-hour tour of the site.

It begins with an hour drive up US 95, a trip that vividly explains why the site is here: The landscape is a mix of wide, flat valleys, perfect for bomb blasts, interrupted by occasional mountain ranges that would discourage unauthorized watchful eyes.

The highlight is a visit to Sedan Crater: a 300-foot-deep, 1,200-foot-wide crater blasted out by a 104-kiloton bomb to see if nuclear devices could be safely used to dig canals and sea ports. The answer, apparently, was “no, they can’t.”

Your guide will take a group picture at Sedan and send it to you later, but that is the one and only souvenir you’ll get: On the Nevada Test Site tour, you can’t take home rock samples and you can’t bring your camera along.

“Oppenheimer Beach,” St. John, USVI

On the eastern shore of Hawksnest Bay in St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands, a low-slung white structure sits on the broad, sugary sand. The building is a community center, but until just a few years ago, before a hurricane swept it away, a tidy wood cottage crouched there. It had been built in the 1950s by a quiet man who periodically arrived with his wife and family, keeping mostly to himself. In his later years, this is where Oppenheimer escaped the stresses of a world he’d helped create. And Hawksnest Bay is where he and his wife had their ashes spread out.

The sun sets over St. John, in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Oppenheimer and his wife and family spent time at a cottage here on Hawksnest Bay in the 1950s. Photograph By Michael Melford, National Geographic Image Collection

Today, locals call the spot Oppenheimer Beach.

Walking this beach, Oppenheimer could wish away the daily reminders of a nuclear arms race, far from the politicians who had exploited his genius to build the bomb and then, as the Nolan film portrays, turned on him when he expressed regret over his accomplishment.

On St. John, “no one was going to harass him,” local historian David Knight, whose parents house-sat for Oppenheimer during his absences, told the BBC. “No one knew who he was or cared.”

#Los Alamos | New Mexico#First Nuclear ☢️ Bomb 💣#Robert J. Oppenheimer#Los Alamos | Birthplace | Atomic Bomb#Christopher Nolan#United States 🇺🇸 National Historic Park#Atomic Blast 💥#Nevada | US 🇺🇸 States#Oppenheimer Beach | St. John | US Virgin Island

1 note

·

View note

Text

As he witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945, a piece of Hindu scripture ran through the mind of J. Robert Oppenheimer: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” It is, perhaps, the most well-known line from the Bhagavad Gita, but also the most misunderstood.

Oppenheimer, the subject of a new film from director Christopher Nolan, died at the age of 62 in Princeton, New Jersey, on February 18, 1967. As wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the birthplace of the Manhattan Project, he is rightly seen as the “father” of the atomic bomb. “We knew the world would not be the same,” he later recalled. “A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.”

Oppenheimer, watching the fireball of the Trinity nuclear test, turned to Hinduism. While he never became a Hindu in the devotional sense, Oppenheimer found it a useful philosophy to structure his life around. “He was obviously very attracted to this philosophy,” says Stephen Thompson, who has spent more than 30 years studying and teaching Sanskrit. Oppenheimer’s interest in Hinduism was about more than a sound bite, Thompson argues. It was a way of making sense of his actions.

The Bhagavad Gita is 700-verse Hindu scripture, written in Sanskrit, that centers on a dialog between a great warrior prince named Arjuna and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Facing an opposing army containing his friends and relatives, Arjuna is torn. But Krishna teaches him about a higher philosophy that will enable him to carry out his duties as a warrior irrespective of his personal concerns. This is known as the dharma, or holy duty. It is one of the four key lessons of the Bhagavad Gita, on desire or lust; wealth; the desire for righteousness, or dharma; and the final state of total liberation, moksha.

Seeking his counsel, Arjuna asks Krishna to reveal his universal form. Krishna obliges, and in verse 12 of the Gita he manifests as a sublime, terrifying being of many mouths and eyes. It is this moment that entered Oppenheimer’s mind in July 1945. “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one,” was Oppenheimer’s translation of that moment in the desert of New Mexico.

In Hinduism, which has a non-linear concept of time, the great god is involved in not only the creation, but also the dissolution. In verse 32, Krishna says the famous line. In it “death” literally translates as “world-destroying time,” says Thompson, adding that Oppenheimer’s Sanskrit teacher chose to translate “world-destroying time” as “death,” a common interpretation. Its meaning is simple: Irrespective of what Arjuna does, everything is in the hands of the divine.

“Arjuna is a soldier, he has a duty to fight. Krishna, not Arjuna, will determine who lives and who dies and Arjuna should neither mourn nor rejoice over what fate has in store, but should be sublimely unattached to such results,” says Thompson. “And ultimately the most important thing is he should be devoted to Krishna. His faith will save Arjuna’s soul." But Oppenheimer, seemingly, was never able to achieve this peace. “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatements can quite extinguish,” he said, two years after the Trinity explosion, “the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

“He doesn’t seem to believe that the soul is eternal, whereas Arjuna does,” says Thompson. “The fourth argument in the Gita is really that death is an illusion, that we’re not born and we don’t die. That’s the philosophy, really. That there’s only one consciousness and that the whole of creation is a wonderful play.” Oppenheimer, perhaps, never believed that the people killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not suffer. While he carried out his work dutifully, he could never accept that this could liberate him from the cycle of life and death. In stark contrast, Arjuna realizes his error and decides to join the battle.

“Krishna is saying you have to simply do your duty as a warrior,” says Thompson. “If you were a priest you wouldn’t have to do this, but you are a warrior and you have to perform it. In the larger scheme of things, presumably, the bomb represented the path of the battle against the forces of evil, which were epitomized by the forces of fascism.”

For Arjuna, it may have been comparatively easy to be indifferent to war because he believed the souls of his opponents would live on regardless. But Oppenheimer felt the consequences of the atomic bomb acutely. “He hadn’t got that confidence that the destruction, ultimately, was an illusion,” says Thompson. Oppenheimer’s apparent inability to accept the idea of an immortal soul would always weigh heavy on his mind.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

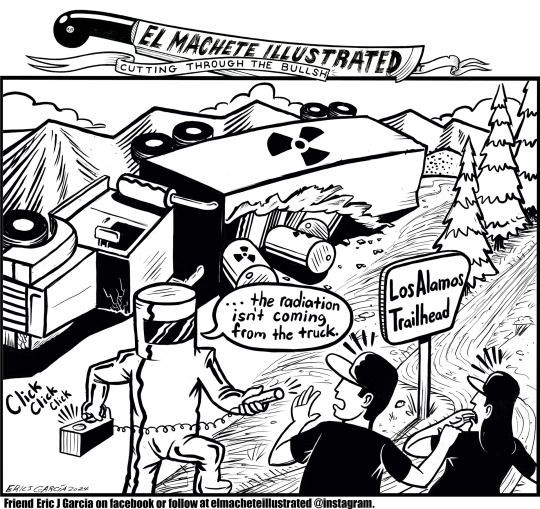

Plutonium found around Los Alamos has nothing to do with the recent munitions accident.

#los alamos#los alamos national labs#manhattan project#new mexico#new mexico true#nuclear#nuclear weapons#nuclear industry#cancer#plutonium#radiation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Southern boom town that is just 24 miles away from dangerous canyon contaminated by plutonium

Daily Mail News By ALEX HAMMER FOR DAILYMAIL.COM PUBLISHED: 06:56 EDT, 15 September 2024 | UPDATED: 15:01 EDT, 15 September 2024 Residents of Santa Fe, New Mexico – less than a half-hour drive from the birthplace of the atomic bomb – are drinking from a water supply with alarming traces of plutonium, scientists have found. The shocking samples were taken from Los Alamos’s soil just 24 miles from…

0 notes

Text

Popular US park as radioactive as Chernobyl, says expert: 'I've never seen anything quite like it'

By Matthew Phelan For Dailymail.Com and Associated Press, 29 August 2024 A scenic hiking trail has been discovered to be dangerously contaminated with radiation. New tests have discovered that Acid Canyon — a popular hiking and biking trail near the birthplace of the atomic bomb, Los Alamos, New Mexico — is still radioactive today at level’s akin to the site of the Soviet Union’s Chernobyl…

0 notes

Text

'...Los Alamos became an open city when the security gates came down in 1957. Still, many parts—including historic sites related to the Manhattan Project—remain off limits. Tourists have to settle for selfies near the town square with the bronze statue of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Across the street, rangers at the Manhattan Project National Historical Park visitor center answer questions about where scientists lived and where parties and town halls were held. A chalkboard hangs in the corner, covered in yellow sticky notes left by visitors. Some of the hand-written notes touch on the complicated legacy left by the creation of nuclear weapons.

It's a conversation that was reignited with the release of Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer." The film put the spotlight on Los Alamos and its history, prompting more people to visit over the summer..'

1 note

·

View note

Text

'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds'. The story of Oppenheimer's infamous quote

The line, from the Hindu sacred text the Bhagavad-Gita, has come to define Robert Oppenheimer, but its meaning is more complex than many realise

Article by James Temperton

As he witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945, a piece of Hindu scripture ran through the mind of Robert Oppenheimer: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”. It is, perhaps, the most well-known line from the Bhagavad-Gita, but also the most misunderstood.

Oppenheimer died at the age of sixty-two in Princeton, New Jersey on February 18, 1967. As wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the birthplace of the Manhattan Project, he is rightly seen as the “father” of the atomic bomb. “We knew the world would not be the same,” he later recalled. “A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.” Oppenheimer, watching the fireball of the Trinity nuclear test, turned to Hinduism. While he never became a Hindu in the devotional sense, Oppenheimer found it a useful philosophy to structure his life around. "He was obviously very attracted to this philosophy,” says Rev Dr Stephen Thompson, who holds a PhD in Sanskrit grammar and is currently reading a DPhil at Oxford University on other aspects of the language and Hindu faith. Oppenheimer’s interest in Hinduism was about more than a soundbite, it was a way of making sense of his actions.

The Bhagavad-Gita is 700-verse Hindu scripture, written in Sanskrit, that centres on a dialogue between a great warrior prince called Arjuna and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Facing an opposing army containing his friends and relatives, Arjuna is torn. But Krishna teaches him about a higher philosophy that will enable him to carry out his duties as a warrior irrespective of his personal concerns. This is known as the dharma, or holy duty. It is one of the four key lessons of the Bhagavad-Gita: desire or lust; wealth; the desire for righteousness or dharma; and the final state of total liberation, or moksha.

Seeking his counsel, Arjuna asks Krishna to reveal his universal form. Krishna obliges, and in verse twelve of the Gita he manifests as a sublime, terrifying being of many mouths and eyes. It is this moment that entered Oppenheimer’s mind in July 1945. “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one,” was Oppenheimer’s translation of that moment in the desert of New Mexico.

In Hinduism, which has a non-linear concept of time, the great god is not only involved in the creation, but also the dissolution. In verse thirty-two, Krishna speaks the line brought to global attention by Oppenheimer. "The quotation 'Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds', is literally the world-destroying time,” explains Thompson, adding that Oppenheimer’s Sanskrit teacher chose to translate “world-destroying time” as “death”, a common interpretation. Its meaning is simple: irrespective of what Arjuna does, everything is in the hands of the divine.

"Arjuna is a soldier, he has a duty to fight. Krishna not Arjuna will determine who lives and who dies and Arjuna should neither mourn nor rejoice over what fate has in store, but should be sublimely unattached to such results,” says Thompson. “And ultimately the most important thing is he should be devoted to Krishna. His faith will save Arjuna's soul." But Oppenheimer, seemingly, was never able to achieve this peace. "In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humour, no overstatements can quite extinguish," he said two years after the Trinity explosion, "the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

“He doesn't seem to believe that the soul is eternal, whereas Arjuna does,” says Thompson. “The fourth argument in the Gita is really that death is an illusion, that we're not born and we don't die. That's the philosophy really: that there's only one consciousness and that the whole of creation is a wonderful play.” Oppenheimer, it can be inferred, never believed that the people killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not suffer. While he carried out his work dutifully, he could never accept that this could liberate him from the cycle of life and death. In stark contrast, Arjuna realises his error and decides to join the battle.

“Krishna is saying you have to simply do your duty as a warrior,” says Thompson. “If you were a priest you wouldn't have to do this, but you are a warrior and you have to perform it. In the larger scheme of things, presumably The Bomb represented the path of the battle against the forces of evil, which were epitomised by the forces of fascism.”

For Arjuna, it may have been comparatively easy to be indifferent to war because he believed the souls of his opponents would live on regardless. But Oppenheimer felt the consequences of the atomic bomb acutely. “He hadn't got that confidence that the destruction, ultimately, was an illusion,” says Thompson. Oppenheimer’s apparent inability to accept the idea of an immortal soul would always weigh heavy on his mind.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Photo

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.' I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

As he witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945, a piece of Hindu scripture ran through the mind of Robert Oppenheimer: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”. It is, perhaps, the most well-known line from the Bhagavad-Gita, but also the most misunderstood.

Oppenheimer died at the age of sixty-two in Princeton, New Jersey on February 18, 1967. As wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory, the birthplace of the Manhattan Project, he is rightly seen as the “father” of the atomic bomb. “We knew the world would not be the same,” he later recalled. “A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.”

Oppenheimer, watching the fireball of the Trinity nuclear test, turned to Hinduism. While he never became a Hindu in the devotional sense, Oppenheimer found it a useful philosophy to structure his life around. He was obviously very attracted to this ancient philosophy. Oppenheimer’s interest in Hinduism was about more than a soundbite, it was a way of making sense of his actions.

The Bhagavad-Gita is 700-verse Hindu scripture, written in Sanskrit, that centres on a dialogue between a great warrior prince called Arjuna and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Facing an opposing army containing his friends and relatives, Arjuna is torn. But Krishna teaches him about a higher philosophy that will enable him to carry out his duties as a warrior irrespective of his personal concerns. This is known as the dharma, or holy duty. It is one of the four key lessons of the Bhagavad-Gita: desire or lust; wealth; the desire for righteousness or dharma; and the final state of total liberation, or moksha.

Seeking his counsel, Arjuna asks Krishna to reveal his universal form. Krishna obliges, and in verse twelve of the Gita he manifests as a sublime, terrifying being of many mouths and eyes. It is this moment that entered Oppenheimer’s mind in July 1945. “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one,” was Oppenheimer’s translation of that moment in the desert of New Mexico.

In Hinduism, which has a non-linear concept of time, the great god is not only involved in the creation, but also the dissolution. In verse thirty-two, Krishna speaks the line brought to global attention by Oppenheimer. "The quotation 'Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds', is literally the world-destroying time. Oppenheimer’s Sanskrit teacher chose to translate “world-destroying time” as “death”, a common interpretation. Its meaning is simple: irrespective of what Arjuna does, everything is in the hands of the divine.

Arjuna is a soldier, he has a duty to fight. Krishna not Arjuna will determine who lives and who dies and Arjuna should neither mourn nor rejoice over what fate has in store, but should be sublimely unattached to such results. And ultimately the most important thing is he should be devoted to Krishna. His faith will save Arjuna's soul.

But Oppenheimer, seemingly, was never able to achieve this peace. “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humour, no overstatements can quite extinguish," he said two years after the Trinity explosion, "the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

#oppeheimer#joseph oppenheimer#quote#atom bomb#manhattan project#nuclear#war#science#physics#ethics#morals#society#civilisation#arjuna#krishna#sanskrit#hindu#history#bhagavad gita#united states#america#world war two#death

106 notes

·

View notes

Link

Biden Has Elevated the Job of Science Adviser. Is That What Science Needs? On the campaign trail, Joseph R. Biden Jr. vowed to unseat Donald J. Trump and bring science back to the White House, the federal government and the nation after years of presidential attacks and disavowals, neglect and disarray. As president-elect, he got off to a fast start in January by nominating Eric S. Lander, a top biologist, to be his science adviser. He also made the job a cabinet-level position, calling its elevation part of his effort to “reinvigorate our national science and technology strategy.” In theory, the enhanced post could make Dr. Lander one of the most influential scientists in American history. But his Senate confirmation hearing was delayed three months, finally being set for Thursday. The delay, according to Politico, arose in part from questions about his meetings with Jeffrey Epstein, the financier who had insinuated himself among the scientific elite despite a 2008 conviction that had labeled him as a sex offender. Dr. Lander met with Mr. Epstein at fund-raising events twice in 2012 but has denied receiving any funding or having any kind of relationship with Mr. Epstein, who was later indicted on federal sex trafficking charges and killed himself in jail in 2019. The long delay in his Senate confirmation has led to concerns that the Biden administration’s elevation of Dr. Lander’s role is more symbolic than substantive — that it’s more about creating the appearance of strong federal support for the scientific enterprise rather than working to achieve a productive reality. Roger Pielke Jr., a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who has interviewed and profiled presidential scientific aides, recently noted that one of President Biden’s top scientific agendas, climate policy, has moved ahead briskly without any help from a White House science adviser. “Is Biden giving him busy work?” he asked of Dr. Lander’s role. “Or is there actually a policy portfolio?” Likewise, Mr. Biden’s first proposed federal budget, unveiled April 9, received no public endorsement from the presidential science adviser but nonetheless seeks major increases in funding at nearly every science agency. Mr. Biden’s championing of the science post and its unpunctual start have raised a number of questions: What do White House science advisers actually do? What should they do? Are some more successful than others and, if so, why? Do they ever play significant roles in Washington’s budget wars? Does Mr. Biden’s approach have echoes in history? The American public got few answers to such questions during Mr. Trump’s tenure. He left the position empty for the first two years of his administration — by far the longest such vacancy since Congress in 1976 established the modern version of the advisory post and its White House office. Under public pressure, Mr. Trump filled the opening in early 2019 with Kelvin Droegemeier, an Oklahoma meteorologist who kept a low profile. Critics derided Mr. Trump’s neglect of this position and the vacancies of other scientific expert positions across the executive branch. But while scientists in the federal work force typically have their responsibilities defined in considerable detail, each presidential science adviser comes into the job with what amounts to a blank slate, according to Shobita Parthasarathy, director of the Science, Technology and Public Policy program at the University of Michigan. “They don’t have a clear portfolio,” she said. “They have lots of flexibility.” The lack of set responsibilities means the aides as far back as 1951 and President Harry S. Truman — the first to bring a formal science adviser into the White House — have had the latitude to take on a diversity of roles, including ones far removed from science. “We have this image of a wise person standing behind the president, whispering in an ear, imparting knowledge,” said Dr. Pielke. “In reality, the science adviser is a resource for the White House and the president to do with as they see fit.” Dr. Pielke argued that Mr. Biden is sincere in wanting to quickly rebuild the post’s credibility and raise public trust in federal know-how. “There’s lots for us to like,” he said. But history shows that even good starts in the world of presidential science advising are no guarantee that the appointment will end on a high note. “Anyone coming to the science advisory post without considerable experience in politics is in for some rude shocks,” Edward E. David Jr., President Richard M. Nixon’s science adviser, said in a talk long after his bruising tenure. He died in 2017. One day in 1970, Mr. Nixon ordered Dr. David to cut off all federal research funding to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Dr. David’s alma mater. At the time, it was receiving more than $100 million a year. The reason? The president of the United States had found the political views of the school’s president to be intolerable. “I just sort of sat there dumbfounded,” Dr. David recalled. Back in his office, the phone rang. It was John Ehrlichman, one of Mr. Nixon’s trusted aides. “Ed, my advice is don’t do anything,” he recalled Mr. Ehrlichman saying. The nettlesome issue soon faded away. In 1973, soon after Dr. David quit, Mr. Nixon eliminated the fief. The president had reportedly come to see the adviser as a science lobbyist. After Mr. Nixon left office, Congress stepped in to reinstate both the advisory post and its administrative body, renaming it the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. The position, some analysts argue, has grown more influential in step with scientific feats and advances. But others say the job’s stature has declined as science has become more specialized and the advisory work has focused increasingly on narrow topics unlikely to draw presidential interest. Still others hold that so many specialists now inform the federal government that a chief White House scientist has become superfluous. But Mr. Biden’s moves, he added in an interview, were now poised to raise the post’s importance and potential sway. “For Democrats,” he said, “science and politics are converging right now, so elevating the status of science is smart. It’s good politics.” The scientific community tends to see presidential advisers as effective campaigners for science budgets. Not so, Dr. Sarewitz has argued. He sees federal budgets for science as having done well over the decades irrespective of what presidential science advisers have endorsed or promoted. Neal F. Lane, a physicist who served as President Bill Clinton’s science adviser, argued that the post was today more important than ever because its occupant provides a wide perspective on what can best aid the nation and the world. “Only the science adviser can be the integrator of all these complex issues and the broker who helps the president understand the play between the agencies,” he said in an interview. The moment is auspicious, Dr. Lane added. Catastrophes like war, the Kennedy assassination and the terrorist attacks of 2001, he said, can become turning points of reinvigoration. So too, he added, is the coronavirus pandemic a time in American history when “big changes can take place.” His hope, he said, is that Mr. Biden will succeed in elevating such issues as energy, climate change and pandemic preparedness. As for the federal budget, Dr. Lane, who headed the National Science Foundation before becoming Mr. Clinton’s science adviser from 1998 to 2001, said his own experience suggested the post could make modest impacts that nonetheless reset the nation’s scientific trajectory. His own tenure, he said, saw a funding rise for the physical sciences, including physics, math and engineering. Some part of his own influence, Dr. Lane said, derived from personal relationships at the White House. For instance, he got to know the powerful director of the Office of Management and Budget, which set the administration’s finances, while dining at the White House Mess. The advisory post becomes most influential, analysts say, when the science aides are aligned closely with presidential agendas. But a commander in chief’s objectives may not match those of the scientific establishment, and any influence bestowed by proximity to the president may prove quite narrow. George A. Keyworth II was a physicist from Los Alamos — the birthplace of the atomic bomb in New Mexico. In Washington, as science adviser to Ronald Reagan, he strongly backed the president’s vision of the antimissile plan known as Star Wars. Dr. Pielke of the University of Colorado said the contentious issue became Dr. Keyworth’s calling card in official Washington. “It was Star Wars,” he said. “That was it.” Despite intense lobbying, the presidential call for weapons in space drew stiff opposition from specialists and Congress, and the costly effort never got beyond the research stage. Policy analysts say Mr. Biden has gone out of his way to communicate his core interests to Dr. Lander — a geneticist and president of the Broad Institute, a hub of advanced biology run by Harvard University and M.I.T. On Jan. 15, Mr. Biden made public a letter with marching orders for Dr. Lander to consider whether science could help “communities that have been left behind” and “ensure that Americans of all backgrounds” get drawn into the making of science as well as securing its rewards. Dr. Parthasarathy said Mr. Biden’s approach was unusual both in being a public letter and in asking for science to have a social conscience. In time, she added, the agenda may transform both the adviser’s office and the nation. “We’re at a moment” where science has the potential to make a difference on issues of social justice and inequality, she said. “I know my students are increasingly concerned about these questions, and think rank-and-file scientists are too,” Dr. Parthasarathy added. “If ever there was a time to really focus on them, it’s now.” Source link Orbem News #adviser #Biden #elevated #Job #Science

0 notes

Photo

Los Alamos lab, birthplace of the atomic bomb, STILL under threat from wildfires despite repeated major incidents https://www.thedailybuzz.io/world-news/los-alamos-lab-birthplace-of-the-atomic-bomb-still-under-threat-from-wildfires-despite-repeated-major-incidents/

0 notes

Text

Atomic Tragedy? Plutonium Levels Near US Nuclear Site In Los Alamos Similar To Chernobyl – New Study.

https://www.eurasiantimes.com/plutonium-levels-at-los-alamos-comparab/—28 Aug 24 Los Alamos, the birthplace of the American atomic bomb under the Manhattan Project led by Robert Oppenheimer, is now facing a troubling revelation. According to a recent study by Northern Arizona University, plutonium levels in the area are alarmingly high, comparable to those found at the Chernobyl nuclear…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

'The Oppenheimer movie has inevitably ignited interest in one of the most contentious episodes of modern history - the birth of a nuclear weapon which unleashed unprecedented destruction.

While the film focuses on the eponymous American physicist spearheading Allied efforts to make the atomic bomb, the team also involved British Nobel Prize winner James Chadwick.

Yet little is known about Chadwick when compared to his peers, whose names read like a who's who of school science lessons.

The shy but steely scientist is credited with discovering the neutron, before going on to lead the British contingent in the Manhattan Project, that was set up to build the atomic bomb.

As World War Two drew to a close, American bombers would drop the devices over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, instantaneously killing more than 100,000 people.

During their development, Chadwick was the only non-American with access to all of the group's research and production plants, according to experts.

He famously admitted his "only remedy" on realising the inevitability of the nuclear bomb was to take sleeping pills, which he ended up doing every night for more than 28 years.

Before his tenure at Los Alamos, Chadwick's career had developed in Manchester, often described as the birthplace of nuclear physics.

The city had become a hub of science and engineering from the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th Century.

But Chadwick's origins 20 miles away never indicated what he would later achieve.

"He was not from any kind of wealthy background," says Dr James Sumner, a historian of technology at the University of Manchester.

"He was certainly not from a traditional academic background."

Born in the Cheshire village of Bollington in 1891, Chadwick himself described his family as poor, with his father failing to set up a business in Manchester.

During an interview later in life, he admitted losing contact with a younger brother, adding: "I'm afraid I don't have a great family feeling."

He "didn't take school very seriously" and recalled playing truant one day with his friend - the headmaster's son - "to go bird-nesting".

"I have quite a vivid memory of being caned very severely for it."

Despite this less than promising start, he later moved to a school in Manchester where he benefited from "extremely good" teaching and gained a university scholarship.

"Manchester then, as now, is a very progressive city indeed," Chadwick recalled, saying he wanted to study mathematics with "no intention whatever of reading physics".

But a mix-up, which involved sitting on the wrong interview bench and being "too shy" to ask for a subject change, inadvertently led to a successful career in physics.

He studied under Prof Ernest Rutherford, the Nobel Prize-winning New Zealander whose model of the atom is still used in schools worldwide.

"You don't let undergraduate students near the monumental, partly because the professors want all the relevant glory for themselves," says Dr Sumner.

"At that time, there were just far fewer physicists and there was more glory to go around, so people like Chadwick could make a difference very early on."

Manchester had been steadily attracting scientific prestige after John Dalton pioneered studies in atomic theory and colour blindness, while fellow student James Joule became a household name after his work in energy conservation.

"Once you've got a big name there, everyone else goes in and makes more discoveries," says Dr William Bodel, who researches nuclear technology at the university in Manchester.

Others to pass through the university included J.J. Thomson - who is credited with discovering the electron - quantum physicist Neils Bohr and Hans Geiger, co-inventor of the radiation counter.

"Chadwick was one of several who did forefront cutting edge research," says Dr Sumner.

"He is publishing forefront discoveries in the hot new science of atomic physics and that's really when his career took off."

He met Albert Einstein on occasions at a Berlin laboratory, where Chadwick was undertaking research with Geiger.

But after World War One broke out, he was imprisoned at a camp when all Englishmen were interned. He still managed to pursue his scientific interests, making a magnet as the German officers - whom he described as "extremely lenient" - turned a blind eye.

On returning to Manchester much weakened and poorer after the war, he was offered work by Rutherford and the pair soon took up opportunities at the University of Cambridge.

His life underwent another change in 1925, when he married Aileen Stewart-Brown in Liverpool and two years later, the couple had twin daughters.

As the science of physics continued to develop, Chadwick proved the existence of the neutron in the early 1930s after some speculative - or "quite silly" as he called it - experiments, following years of believing it was a main constituent of the nucleus.

"When I did the experiments, as I did off and on, they were done at odd moments and sometimes when nobody was about," he said.

Yet Dr Bodel describes the discovery as "fundamental enough to teach to school children".

"Before him, it was known there was an extra particle, but it was difficult to detect."

Chadwick said "it hadn't crossed my mind" that the breakthrough would earn him the 1935 Nobel Prize for Physics but, in his typically succinct way, he said he was "naturally, extremely pleased".

The prize came at a parting of the ways with his mentor Rutherford, as they differed about new equipment to advance their research.

Chadwick took up the offer as chair of physics at the University of Liverpool, saying he also wanted "more contact with other people with different interests".

Following the outbreak of another world war, his expertise saw him join a British working group to study the possibility of developing a nuclear weapon.

A destructive legacy

In 1943, Chadwick travelled as head of the British mission to Los Alamos in the US, where scientists were developing the first atomic bomb.

But he felt "much more needed in Washington to keep in touch with our people there and to see what was happening in different places".

He worked closely with project chief Lt General Leslie Groves, played in the film by Matt Damon, and spoke rarely about laboratory director Oppenheimer or "Oppie" as he called him.

However, there were concerns "other countries would take up the business", according to Chadwick.

"I was quite sure, you see, that the Russians could not be far behind in knowing about the project."

Chadwick believed British participation was "helpful", even though "perhaps we had not many contributions to make".

The explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed more than 100,000 people, with more dying from the impact by the end of 1945.

"It completely changed the way we operate," says Dr Bodel. "The world was not the same after the Hiroshima bomb. We can't underestimate their contribution."

Despite Chadwick's discomfort at the devastating impact, he went on to lobby for the UK to have its own nuclear arsenal after the war.

"I don't have any doubts that the bomb had to be used. And I don't feel any guilt in having taken part in producing it. Why should I? Far worse things happened than that — perhaps not many," he said.'

#Oppenheimer#James Chadwick#Los Alamos#John Dalton#Prof Ernest Rutherford#James Joule#J.J. Thomson#Niels Bohr#Hans Geiger#Albert Einstein#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon

0 notes

Text

Star Wars: Episode IX Working Title Revealed

SPOILERS for Star Wars: The Last Jedi ahead

The working title of Disney and Lucasfilm’s Star Wars: Episode IX has been revealed to be Black Diamond. The latest installment in the new trilogy set in a galaxy far, far away, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, is proving to be a box office juggernaut, raking in a staggering $450 million global opening. In the U.S. alone, Rian Johnson’s Episode VIII earned $220 million at the domestic box office.

Lucasfilm’s attention, though, is moving on to the next chapter in the Star Wars saga. Just two days ago, J.J. Abrams pitched Episode IX‘s story to Lucasfilm. The studio seems to have jumped into hyperspace on the final film in the sequel trilogy, and today we’ve learned the movie’s working title.

Fantha Tracks revealed that the working title is Black Diamond. It’s worth noting that this site broke the working titles of The Last Jedi (Space Bear) and Rogue One(Los Alamos). As a result, they can be considered a pretty reliable source. Lucasfilm tends to open separate production companies in the UK to produce their Star Wars films. Foodles Production (UK) Ltd, for example, managed The Force Awakens. Space Bear Industries (UK) Ltd handled The Last Jedi. According to Fantha Tracks, the production company for Episode IX is Carbonado Industries (UK) Ltd. A carbonado is the toughest form of natural diamond, commonly known as a Black Diamond.

It seems Lucasfilm originally intended to use Carbonado Industries to produce Solo, in a nod to his being frozen in carbonite. Plans changed though, and delays to the Boba Fett movie meant Stannum 50 Labs (UK) Ltd picked up Solo instead.

Working titles vary in terms of their significance. Rogue One‘s working title, for example, was particularly appropriate. The working title was a reference to the town of Los Alamos, birthplace of the atomic bomb. Considering the movie focused on the creation of the Death Star, that’s an amusing nod. On the other hand, The Last Jedi‘s working title — Space Bear — seems pretty irrelevant.

It’s too soon to tell whether or not Episode IX‘s working title bears any significance. Nobody quite knows how Black Diamonds are formed, but a common theory is that it’s under high-pressure conditions in the Earth’s mantle. It may be that Rey is the Black Diamond, her heroism formed under the chaos of the First Order’s reign. Meanwhile, the diamonds are known for their luminescence, prompting Fantha Tracks to speculate that we’ll see some “luminescent” beings in the film. After all, there’s no reason Luke couldn’t return as a Force ghost.

It’s probably wise to take these theories with a pinch of salt. Lucasfilm intended Solo to be produced by Carbonado Industries, not Episode IX. The working title is clearly derived from the company name, so may have no meaning at all for the film. We’ll likely learn more when production starts next year.

Source: Screenrant

18 notes

·

View notes