#Laurence Keitt

Text

The wedding must have been so bad.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

February 6th 1858: Brawl in the House of Representatives

On this day in 1858, in the early hours of the morning, a fight broke out in the U.S. House of Representatives. The altercation began between Laurence Keitt of South Carolina and abolitionist Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania. The two had been engaged in a particularly fraught debate over the Kansas controversy. Since the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, the territory had become a hotbed of sectional violence between Northerners and Southerners who rushed to the area to claim the land as free or slave respectively. Keitt and Grow were debating the merits of the Lecompton Constitution, the pro-slavery document drafted by the fraudulently-elected Kansas convention that President Buchanan wanted Congress to support in order to admit Kansas as a slave state. Keitt had a history of involvement with violence in the halls of Congress. In 1856, he prevented others from coming to the aid of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner as he was savagely beaten by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks. The 1858 conflict began when Grow crossed to the Democratic side of the chamber to consult a colleague, causing Keitt to become incensed and call Grow a ‘black Republican puppy’. Grow shot back calling Keitt a 'negro-driver’, and with that the House descended into an open brawl. The Speaker and Sergeant-at-Arms, wielding the ceremonial mace, failed in their attempts to restore order. The fight finished in a particularly absurd manner, with Wisconsin Representative John Potter pulling the toupee from Mississippi Representative William Barksdale’s head, causing the floor to erupt in laughter when he put it back on the wrong way round.

“Hooray, boys! I’ve got his scalp!”

- What Potter supposedly said when he seized Barksdale’s wig

#history#today in history#this day in history#on this day in history#american history#us history#house#house of representatives#political history#civil war#american civil war#civil war america#congress#congressional history#laurence keitt#galusha grow#quote#1858

427 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking Forward/Looking Back

And so a new era begins in our nation! Will the Biden years, whether four or eight of them, lead to healing in a nation so riven that many of the chasms that divide us—some racial, others political, still others ethnic or economic—feel truly unbridgeable? Will they feature an end to the COVID-era that has so radically altered the way we live and do business in our land? Will they bring a rededication to the kind of environmentally sound public policy that could possibly head off the crises that will otherwise visit the planet with increasingly frequency and ferocity if we choose to put blinders on and then recklessly to barrel ahead into uncharted waters without any clear sense of how to address even the issues that threaten us the least overtly, let alone those that are the most prominent? Will the recent hopeful developments in the Middle East serve as the prelude to the kind of complex reconfiguration that will, at long last, make Israel into a nation tied at least as profoundly to neighbors and local friends as to distant allies in North America and, when the wind blows in the right direction, Europe? (And will such a rebalancing of alliances lead finally to a just resolution of the Palestinians’ plight in a way that both serves their own best interests and Israel’s?) All of these questions are in the air as we pass from the Trump era to the Biden years, definitely from the past to the future and ideally from a period characterized by unprecedented (that word again!) incivility and fractiousness to one more reminiscent of the nation in which people my age and older remember growing up.

To none of the above questions do I have a clear answer to offer. But I do feel hopeful—and that hope is born not merely of wishful thinking (or not solely of it), but also of a sense that we have come to a point in our nation’s history at which the task of re-dedicating ourselves to the bedrock notions that underlay the founding of the American republic in the eighteenth century is crucial. But no less crucial is ridding ourselves of some of the fantasies we have been taught since childhood to accept as basic American truths.

There are lots to choose from, but today I would like to write about one of my favorite American fantasies, the one according to which Americans have always treated dissent graciously, enjoying national debate without acrimony and finding in principled dialogue the most basic of American paths forward. According to that fantasy, Congress exists basically to house friendly co-workers whose disagreements can and do yield the kind of dignified compromise that in turn serves as a path forward that all their constituents can gratefully travel into a bipartisan future built on our collective will to live in peace and learn from each other. Hah!

We have had in our past instances of violent altercation, including some in the very halls of Congress that were besieged by insurrectionists on January 6. Forgetting them won’t necessarily condemn us to reliving them. But keeping them in mind will surely help us find the resolve to avoid them. As we enter the Biden years, we need to look with clear eyes on that part of our history and, instead of ignoring it, allow it to guide us forward into a different kind of future.

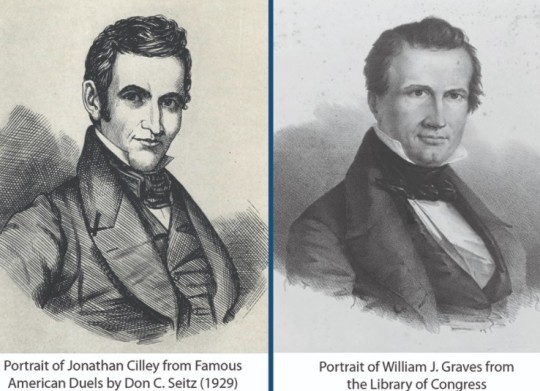

First up, I think, would have to be the 1838 murder of Congressman Jonathan Cilley (D-Maine) by Congressman William Graves (Whig-Kentucky). This one did not take place in the Capitol, although that’s where the party got started. The backstory is so petty as almost to be silly, yet a man died because of that pettiness. Cilley said something on the floor of the House that irritated a prominent Whig journalist, who responded by asking Graves to hand deliver a note demanding an apology. Cilley declined, to which principled decision Graves responded by challenging Cilley to a duel, which then actually took place on February 24, 1838 in nearby Maryland. Neither was apparently much of a marksman. Both men shot twice and missed. But then Congressman Graves aimed more carefully and shot and killed Congressman Cilley.

To their credit, Congress responded by passing anti-dueling legislation. But that only kept our elected representatives from murdering each other, not from behaving violently. For example, when Representative Preston Brooks (D-South Carolina) wanted to express his disapproval of the abolitionist stance of Senator Charles Sumner (R-Massachusetts), he brought a walking cane with him into the Capitol on May 22, 1856, and beat Sumner almost to death. The account of the beating on the website of the United States Senate reads as follows: “Moving quickly, Brooks slammed his metal-topped cane onto the unsuspecting Sumner's head. As Brooks struck again and again, Sumner rose and lurched blindly about the chamber, futilely attempting to protect himself. After a very long minute, it ended. Bleeding profusely, Sumner was carried away. Brooks walked calmly out of the chamber without being detained by the stunned onlookers.” The rest of the story is also instructive: Congress voted to censure Congressman Brooks, whereupon the latter resigned and was almost immediately re-elected to the House by his constituents in South Carolina. He died soon after that (and at age 37), but his place in history was secured! Sumner himself survived and spent another eighteen years in the Senate.

I’d like to suggest that all my readers who felt totally shocked by the events of January 6 to read The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War by Joanne B. Freeman, a professor of history at Yale University, that was published in 2018 by Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux. I read the book when it came out and thought then (and still do think) that it should be required reading for all who imagine that, as I keep hearing, the use of violence and, even more so, the threat of violence “just isn’t us.” It’s us, all right. And Freeman’s book proves it a dozen different ways. As readers of my letters know, I read a lot of American history. But I can hardly recall reading a book that so thoroughly changed the way I thought of our government and its history.

And then there was the brawl in the House in 1858 that broke out when Laurence M. Keitt (D-South Carolina) attempted to strangle Galusha Grow (R-Pennsylvania) in the wake the latter speaking disparagingly about of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford to the effect that Black people were by virtue of their race excluded from American citizenship regardless of whether they were enslaved or free. The House was, to say the least, riven when Keitt went for Grow’s throat. And what happened next, Freeman writes, “was a free-for-all right in the open space in front of the Speaker’s platform featuring roughly thirty, sweaty, disheveled, mostly middle-aged congressman in a no-holds-barred brawl, North against South.” Keitt, who threw the first punch, was already known as a violent man: it was he, in fact, who took out his gun and threatened to kill any member of Congress who was part of the effort to save Charles Sumner’s life in the attack on him by Preston Brooks mentioned above.

These are the thoughts I have in my heart as the nation enters the Biden years. We have a history of violence, incivility, and public rage. What happened on January 6 was, yes, an aberration in that no one supports—or, at least, supports openly—the use of violence to make a point in the Congress. But that was not something new and shocking as much as it was a return to an earlier stage of our nation’s history, a kind of regression to the days in which violence was the language of discourse, an age in which it was possible for one member of the House openly to attempt to strangle another and then to suffer no real consequences at all. And just to wrap up the story, Representative Keitt later joined the Confederate Army and was killed on June 1, 1864 at the Battle of Cold Harbor near Mechanicsville, Virginia.

That we can renounce violence, embrace civility, listen to opposing viewpoints carefully and thoughtfully, debate with courage and respect for others’ opinions, and behave like grown-ups even when we are unlikely to have our way in some matter of public policy—I know in my heart that we can do that. Last week, I wrote about three different instances of armed insurrection against the federal government. This week, I’ve written about the use of threats of violence, and violence itself, at the highest level of government. I could go on to note that, of our first forty-five American presidents, there have been either successful or unsuccessful assassination attempts against a full twenty of them…and that that list includes every president of my own lifetime except for Dwight Eisenhower. We cannot renounce our American propensity to settle things with our fists by making believe that violence is not part of our culture. Just the opposite is true: it was part of our past and it certainly part of our present. Whether it will be part of our future—that is the question on the table. The insurrectionists who entered the Capitol on January 6 were convinced they were acting in accordance with American tradition. There’s something to that argument too…and that is why it is so crucial now that we all join together to renounce that part of our past and then to move ahead into a future characterized by mutual respect, respectful debate, and a deep sense of national unity born of pride in the best parts of our past, confidence in the present, and hope in the future.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On This Day in History February 6, 1858: If you thought that tensions in American politics were running high and surprised that punches have yet to been thrown, check out this historical tidbit. In an ongoing session of Congress a brawl breaks out between multiple members of Congress started by insults and blows thrown by Pennsylvania Republican Galusha Grow and South Carolina Democrat Laurence Keitt. The reason for the melee? The debate over the Kansas Territory’s pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution.

According to the post The Most Infamous Floor Brawl in the History of the U.S. House of Representatives February 06, 1858 from the History, Art and Archives webpage of the House of Representatives website:

More than 30 Members joined the melee. Northern Republicans and Free Soilers joined ranks against Southern Democrats. Speaker James Orr, a South Carolina Democrat, gaveled furiously for order and then instructed Sergeant-at-Arms Adam J. Glossbrenner to arrest noncompliant Members. Wading into the “combatants,” Glossbrenner held the House Mace high to restore order. Wisconsin Republicans John “Bowie Knife” Potter and Cadwallader Washburn ripped the hairpiece from the head of William Barksdale, a Democrat from Mississippi. The melee dissolved into a chorus of laughs and jeers, but the sectional nature of the fight powerfully symbolized the nation’s divisions. When the House reconvened two days later, a coalition of Northern Republicans and Free Soilers narrowly blocked referral of the Lecompton Constitution to the House Territories Committee. Kansas entered the Union in 1861 as a free state.

For an interesting blow-by-blow breakdown of the Congressional Capitol Combat, I suggest you read Jeff Nilsson’s Beatings, Brawls, and Lawmaking: Mayhem in Congress from the Saturday Evening Post dated December 4, 2010

It makes you wonder with the sizzling hot political climate surrounding the Trump administration, if our representatives in Congress will engage in some fisticuffs in the near future. We’ll have to wait see.

For Further Reading:

Beatings, Brawls, and Lawmaking: Mayhem in Congress by Jeff Nilsson from the Saturday Evening Post dated December 4, 2010

#Brawl in Congress#Congressional History#Galusha Grow#Capitol Combat#Laurence Keitt#Political Science#American History#U.S. History#On This Day in History#This Day in History#History Today#Today in History#History#Historia#Histoire#HistorySisco#History Sisco

0 notes

Text

The Violence at the Heart of Our Politics

By Joanne B. Freeman, NY Times, Sept. 7, 2018

Mike Huckabee waxed historic this week while denouncing protesters who interrupted Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings. “Clear the room or start caning them when they open their yaps!” he tweeted, making a backhanded reference to the most famous caning in American history: the 1856 attack on Senator Charles Sumner. Outraged by one of Sumner’s antislavery speeches, Preston Brooks of South Carolina brutally beat him to the ground in the Senate chamber a few days later, stopping only when his cane broke.

Clearly, the United States has a long and storied history of polarizing crises. The 1960s was one such time, as were the late 1790s; in both cases, Americans of opposing politics turned on each other with violent outcomes. The 1850s were even more severe. The period’s raging debate over slavery fractured political parties, paralyzed the national government and divided the nation. In time, this struggle tore the nation apart.

In many ways, the crisis of the 1850s played out on the floor of Congress, the focus of national politics for much of the 19th century. A forum for national debate with the power to decide the fate of slavery, it became a bullpen for sectional combat, with armed clusters of Northerners and Southerners defending their interests with fists and weapons as well as legislation.

Some of the furor wasn’t slavery related; antebellum America was inherently violent, as was its politics, and Congress is a representative institution. The mighty oratory of the 1830s and ‘40s was accompanied by an undercurrent of brute force. Threats and fistfights were part of the political game, and congressmen sometimes put such violence to legislative purpose.

More often than not, such bullies were Southerners or Southern-born Westerners. So-called fighting men promoted their interests and silenced their foes with insults, fists, canes, knives, pistols and the occasional brick, giving them a literal fighting advantage over “noncombatants,” who were usually Northerners. Sumner’s brutal caning was far from the only violent incident in Congress.

In fact, in the course of researching how the culture of politics changed after the 1790s--the subject of my first book--I uncovered roughly 70 physically violent political confrontations between 1830 and the Civil War, most of them in the House and Senate chambers, a few on nearby streets and dueling grounds. Fistfights, shoving matches, weapon wielding, mass brawls: Largely forgotten now, these clashes show a momentous political struggle unfolding in real time.

Initially, most of the fighting centered on matters of personal honor, party loyalty or regional pride. Take, for example, the 1838 duel between Representatives Jonathan Cilley, a Democrat from Maine, and William Graves, a Whig from Kentucky. Although their duel had dire consequences, it was sparked by little more than political name-calling in the House. When Henry Wise, a Virginia Whig and a notorious bully, suggested that an unnamed Democratic congressman was corrupt, Cilley leaped to the defense of his party. Wise then did what bullies were wont to do: He tried to silence his opponent by taunting him with a duel challenge and then declaring him too cowardly to fight. Like many a Northerner, Cilley faced a difficult choice. Should he ignore Wise’s taunts and risk dishonoring himself and his constituents by proxy? Or should he risk fighting a duel and be ostracized by his constituents for engaging in a barbaric Southern practice?

In the end, Cilley opted to fight, though not with Wise. Because of the niceties of the code duello, and a chain of Whigs who took offense at Cilley’s actions, he ultimately fought a duel with Graves, who had done nothing more than hand Cilley a message from a far more belligerent Whig. Cilley and Graves liked each other fine; there was no ill will between them. But for the sake of their regions, their states, their parties and their reputations, both men felt compelled to fight a duel, and only one man survived it. Cilley was 35 years old when he died.

The growing immediacy of the problem of slavery made matters worse. Congressional brawling increasingly pitted North against South, fracturing national parties across sectional lines and rendering routine congressional violence far less tractable. Westward expansion set off a desperate debate over the slavery status of new states, and Southern congressmen defended their slave regime by attempting to silence antislavery advocates with threats and violence.

Take, for example, Representative John Dawson, a Democrat from Louisiana. Dawson routinely wore both a Bowie knife and a pistol, and he wasn’t shy about using them in the House, particularly when someone dared to attack slavery. In 1842, when Thomas Arnold, a Whig from Tennessee, defended John Quincy Adams’s right to discuss antislavery petitions, Dawson strutted over to Arnold with his knife plainly visible and threatened to cut his throat “from ear to ear.”

Dawson went even further three years later in what may well be the all-time greatest display of firepower on the floor. When the Ohio abolitionist Joshua Giddings gave an antislavery speech, Dawson, clearly agitated, positioned himself in front of Giddings, vowing to kill him, and cocking his pistol. Four armed Southern Democrats immediately joined him, which prompted four Whigs to position themselves around Giddings, several of them armed as well. After a few minutes, the pistoleers sat down. But the potential for bloodshed was very real.

The 1854 debate over the Kansas-Nebraska Act made matters worse. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise had drawn a virtual line across the country separating the free North from the slaveholding South. The Kansas-Nebraska Act seemingly undid that compromise, enabling future states to decide slavery’s fate on their own through popular sovereignty. Not surprisingly, debate over the act raised the passions of the slavery debate--and congressional violence--to new heights.

The press amplified the crisis. In their efforts to rouse public sentiment for or against the act, newspapers promoted conspiracy theories about sectional plots to seize control of the Union. Antislavery papers argued that an organized “Slave Power” was trying to spread slavery throughout the Union by stifling Northern opposition. Pro-slavery papers insisted that Northern aggressors were trying to isolate and destroy the slaveholding South. New technologies like the telegraph broadcast these accusations with ever-increasing speed and reach throughout the nation, and did just what editors and reporters hoped they would do: outrage the public and encourage them to fight for their rights and demand the same of their congressmen.

The Republican Party was born of this furor. The arrival of a Northern antislavery party in Congress caused violence to spike. Dedicated to fighting the Slave Power, Republican congressmen did their duty, confronting Southerners as never before, and Southerners replied in kind. Sumner’s caning was of a piece with this wave of violence. Slavery supporters saw his raging antislavery rhetoric as proof of Northern attempts to degrade and subjugate the South. Antislavery advocates, in turn, saw Brooks, Sumner’s attacker, as part of a Slave Power plot to dominate the North. Joined with some recent assaults on Northern congressmen and the rising intensity of antislavery efforts, for Northerners and Southerners alike, the caning seemed to prove the existence of a sectional conspiracy to seize national control.

One House brawl in 1858 shows such thinking in action. During an overnight debate about slavery in Kansas, Galusha Grow--a feisty Pennsylvania Republican--raised an objection while standing amid Southern Democrats. One of those Democrats--the equally feisty Laurence Keitt of South Carolina--immediately took offense, insisting that Grow object on his own side of the House. When Grow declared that it was a free hall and he could do as he liked, Keitt stalked over to Grow, mumbling “We’ll see about that,” and grabbed his throat in preparation to throw a punch. Grow responded by slugging Keitt hard enough to knock him flat.

A horde of Southern Democrats--many of them armed--immediately rushed toward the combatants, some to calm things down, others to attack Grow, a living embodiment of Northern aggression. Seeing the rush of Southerners, a stream of Republicans--some of them also armed--raced to the point of conflict, leaping onto chairs and desks in their hurry to save a fellow under fire. The end result was an enormous brawl in front of the House speaker’s chair featuring punching, shoving and tossed spittoons.

To onlookers in Congress and the country alike, the implications of the Grow-Keitt rumble were clear: North and South had gone to war in the House chamber. Congressmen on each side assumed that the other side was angry, overbearing and itching for a fight. This distrust was no back-of-the-mind matter of speculation. It was immediate. Both sides jumped into action in seconds. And the public shared these suspicions. By the late 1850s, Northerners and Southerners alike were urging their congressmen to fight--literally--for their rights. Some Northerners even gave guns to their congressmen, who were less likely to carry arms than their Southern colleagues. Distrustful of each other and of Congress’s ability to contain their struggle, Americans were prepared for open combat in the Capitol.

The lessons of this breakdown are severe. It shows what can happen when polarized politics erodes the process of debate and compromise at the heart of republican government. Americans lose faith in their system of government and ultimately lose faith in one another. Splintering political parties can’t contain the damage. Violence begins to seem logical, even necessary. And the press can fuel this distrust with conspiracy theories and extremist spin; the antebellum press wasn’t in the business of objectivity--and it mattered.

The destructive power of the press becomes even more marked when spread with new technologies. In the 1850s, the telegraph confronted Americans with a steady stream of virtually instant information: contradictory, confusing, overlapping and inaccurate, it scrambled and intensified the political climate. Today, social media is doing the same. At its heart, democracy is a continuing conversation between politicians and the public; it should come as no surprise that dramatic changes in the modes of conversation cause dramatic changes in democracies themselves.

If Congress’s checkered past teaches us anything on this score, it teaches this: A dysfunctional Congress can close off a vital arena for national dialogue, leaving us vulnerable in ways that we haven’t yet begun to fathom.

Joanne B. Freeman is a professor of history and American studies at Yale, a co-host of the history podcast “BackStory” and the author of the forthcoming book “The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War.”

0 notes

Text

Since the earliest days of the Republic, those supporting strong federal government found themselves opposed by those favoring of greater self-determination by the states. In the southern states, climate conditions led to dependence on agriculture, the rural economies of the south producing cotton, rice, sugar, indigo and tobacco. Colder states to the north tended to develop manufacturing economies, urban centers growing up in service to hubs of transportation and the production of manufactured goods.

In the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. A lion’s share of this revenue was collected in the south, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of this federal largesse was spent in the north, with the construction of railroads, canals and other infrastructure.

The debate over economic issues and rights of self-determination, so-called ‘state’s rights’, grew and sharpened with the “nullification crisis” of 1832-33, when South Carolina declared such tariffs to be unconstitutional and therefore null and void within the state. A cartoon from the time depicted “Northern domestic manufacturers getting fat at the expense of impoverishing the South under protective tariffs.”

Chattel slavery pre-existed the earliest days of the colonial era, from Canada to Brazil and around the world. Moral objections to what was really a repugnant practice could be found throughout, but economic forces had as much to do with ending the practice, as any other. The “peculiar institution” died out first in the colder regions of the US and may have done so in warmer climes as well, but for Eli Whitney’s invention of a cotton engine (‘gin’) in 1792.

It takes ten man-hours to remove the seeds to produce a single pound of cotton. By comparison, a cotton gin can process about a thousand pounds a day, at comparatively little expense.

The year of Whitney’s invention, the South exported 138,000 pounds a year to Europe and the northern colonies. Sixty years later, Great Britain alone was importing 600 million pounds a year from the southern states. Cotton was King, and with good reason. The stuff is easily grown, is easily transportable, and can be stored indefinitely, compared with food crops. The southern economy turned overwhelmingly to the one crop, and its need for plentiful, cheap labor.

The issue of slavery had joined and become so intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable.

The first half of the 19th century was one of westward expansion, generating frequent and sharp conflicts between pro and anti-slavery factions. The Missouri compromise of 1820 attempted to reconcile these factions, defining which territories would legalize slavery, and which would be “free”.

The short-lived “Wilmot Proviso” of 1846 sought to ban slavery in new territories, after which the Compromise of 1850 attempted to strike a balance. The Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 created two new territories, essentially repealing the Missouri Compromise and allowing settlers to determine their own direction.

This attempt to democratize the issue had the effect of drawing up battle lines. Pro-slavery forces established a territorial capital in Lecompton, while “antis” set up an alternative government in Topeka.

In Washington, Republicans backed the anti-slavery side, while most Democrats supported their opponents. On May 20, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner took to the floor of the Senate and denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Never known for verbal restraint, Sumner attacked the measure’s sponsors Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (he of the later Lincoln-Douglas debates), and Andrew Butler of South Carolina by name, accusing the pair of “consorting with the harlot, slavery”. Douglas was in the audience at the time and quipped “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool”.

In the territories, the standoff had long since escalated to violence. Upwards of a hundred or more were killed between 1854 – 1861, in a period known as “Bleeding Kansas”.

The town of Lawrence was established by anti-slavery settlers in 1854, and soon became the focal point of pro-slavery violence. Emotions were at a boiling point when Douglas County Sheriff Samuel Jones was shot trying to arrest free-state settlers on April 23, 1856. Jones was driven out of town but he would return.

Sack of Lawrence, Kansas

The day after Sumner’s speech, a posse of 800 pro-slavery forces converged on Lawrence Kansas, led by Sheriff Jones. The town was surrounded to prevent escape and much of it burned to the ground. This time there was only one fatality; a slavery proponent who was killed by falling masonry. Seven years later, Confederate guerrilla Robert Clarke Quantrill carried out the second sack of Lawrence. This time, most of the men and boys of the town were murdered where they stood, with little chance to defend themselves.

Meanwhile, Preston Brooks, Senator Butler’s nephew and a Member of Congress from South Carolina, had read over Sumner’s speech of the day before. Brooks was an inflexible proponent of slavery and took mortal insult from Sumner’s words.

Preston Brooks (left), Charles Sumner, (right)

Brooks was furious and wanted to challenge the Senator to a duel. He discussed it with fellow South Carolina Democrat Representative Laurence Keitt, who explained that dueling was for gentlemen of equal social standing. Sumner was no gentleman, he said, no better than a drunkard.

Brooks had been shot in a duel years before, and walked with a heavy cane. Resolved to publicly thrash the Senator from Massachusetts, the Congressman entered the Senate building on May 22, in the company of Congressman Keitt and Virginia Representative Henry A. Edmundson.

The trio approached Sumner, who was sitting at his desk writing letters. “Mr. Sumner”, Brooks said, “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.”

Sumner’s desk was bolted to the floor. He never had a chance. The Senator began to rise when Brooks brought the cane down on his head. Over and over the cane down, while Keitt brandished a pistol, warning onlookers to “let them be”. Blinded by his own blood, Sumner tore the desk from the floor in the struggle to escape, losing consciousness as he tried to crawl away. Brooks rained down blows the entire time, even after the body lay motionless, until finally, the cane broke apart.

In the next two days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals, on the banks of Pottawatomie Creek.

The 80-year-old nation forged inexorably onward, to a Civil War which would kill more Americans than every war from the American Revolution to the War on Terror, combined.

May 22, 1856 State’s Rights Since the earliest days of the Republic, those supporting strong federal government found themselves opposed by those favoring of greater self-determination by the states.

0 notes