#Latvian Folk Tales

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

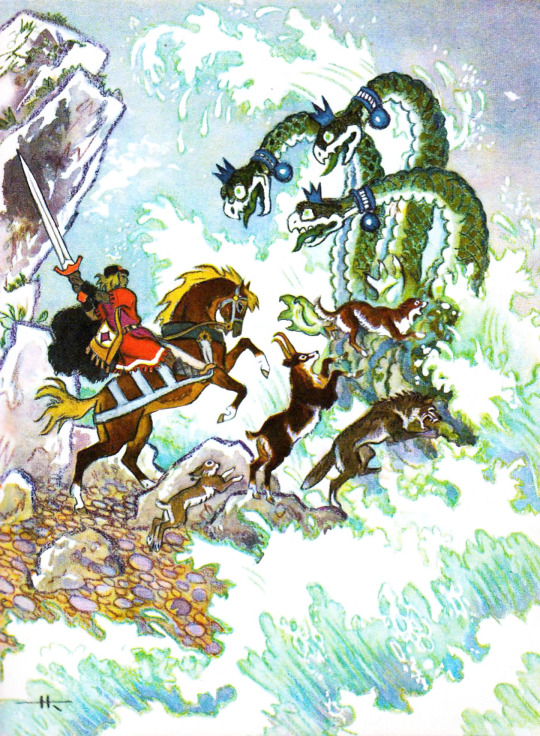

Nikolai Kochergin (1897-1974), ''The White Deer- A Latvian Folk Tale'' by Fainna Solasko, 1973 Source

#Nikolai Kochergin#russian artists#the white deer#Latvian Folk Tales#Fainna Solasko#folk tales#children's books#children's illustration

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

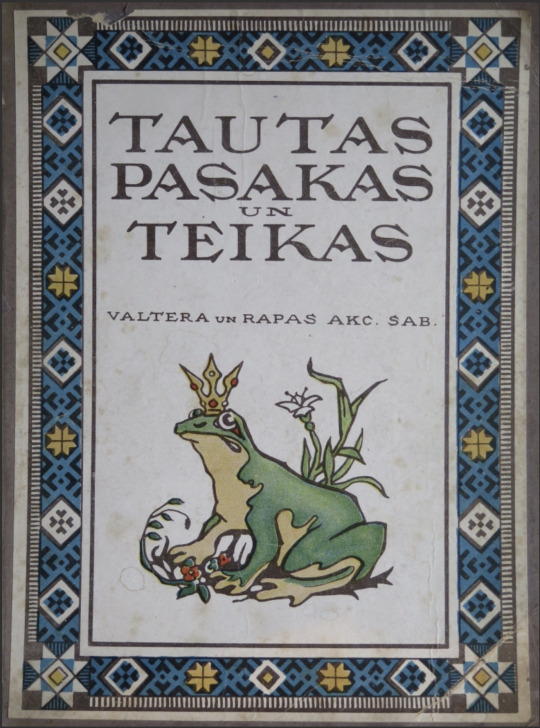

Book cover illustration by Edvards Brencēns (Latvian 1885-1929), Tautas pasakas un teikas (Folk Tales and Fables), 1923.

#illustrations#book cover design#Latvian art#Latvian artwork#Latvian illustrations#Latvian book cover#Edvards Brencēns#folk tales#fables#frog

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey, quick question:

How did you manage to create an intricate original fantasy world? I find myself struggling to come up with, well, practically any proper original worldbuilding and I am in awe (and even a bit envious) of your prowess from what I know of your original world. So, how did you manage, how did you get the spark that became that world?

Oh, not sure where to begin. It's kind of a sensitive thing. I can't give any good advice bc building things in my mind is how I cope with the world.

The world (or rather an imaginary island that exists somewhere on our planet, I don’t actually like creating large scale whole worlds because I’m detail driven and I’d go insane mapping the streets of an entire globe) was made as a place for existing OC stories to take place. I had designed folks for various game settings and eventually in 2013 I got this thought that maybe I should try to connect the legs of these character AUs to the body of the spider, the one main world - Sydrathna.

The island itself was frankensteined together on the basis of "oh I want this oc to do this in a place like this" and just piled it up until something bigger formed. I get a random thought and go - yeah I’ll add that to the lore. And have been doing this for over ten years now. It doesn’t have to make sense at first. Get an idea and start knitting around it (aka connecting one OC's story to anothers to form a timeline) and it will eventually blend in. Its extra fun stuff when two OCs come from very different backgrounds and have to connect.

Biggest inspirations for my personal setting are classic fairy tales and media that has the vibes. Latvian folk stories, Irish folk stories, H.C. Andersen's fairy tales. Chronicles of Narnia for the portal connecting the surface and "underwater" sections of the island.

Tldr: I don't know what I'm doing but it's fun so I'm doing it.

#asks & answers#ritens oc#i gotta find and share the map WIP i was woeking on. its a messy jumble but uh#Sydrathna

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

clearing out the drafts of Random Things I've Noticed if you can't tell but here, have another one - this building on the end of aziraphale's row of shops, on the other side of the record shop:

now im fairly certain about two things. first, it's called 'Alf Laylah wa-Laylah' - translated to english from arabic as One Thousand and One Nights. i can't quite tell at this quality if the writing below it is hebrew or yiddish, nor if it's a translation of the text above it (although, as best as i can tell? it isn't? but not sure)

im also not entirely sure on the relevance of the reference - if there is any to be had - to the story compilation that is One Thousand and One Nights, to tell the truth. the immediate thought that springs to mind is how scheherazade tells the king countless folk tales and stories over 1001 nights in order to keep him in suspense of hearing how the stories end - so he essentially stops killing women as revenge for the infidelity of his wife (it's a whole thing), whom he eventually pardons/spares from execution.

all the tales - as well as returns to the 'present' - include debate on philosophies and ethics, and explore various themes and topics, but regardless... my thoughts are somewhat jumping between this, the questions around the reliability of events as presented in s2, the flashbacks and the Lessons, etc. maybe that's not the link to make here, but it's all im coming up with so far.

but back to the building, and the second thing: think that the stars on the bottom half of the building, in the specific configuration they're shown, are the kaheksakand (estonian) / auseklis (latvian) - an eight-pointed star representing fertility and life, the triumph of light over darkness, as well as used as a protection symbol against evil (aptly placed outside the door).

there's a lot to go into re: the symbology behind '8', including its relationship to the concept of balance and harmony, especially in nature. the eight-pointed star in general, not just in the above exact shape, has dozens of cultural, religious, and mythological links (tbh it's probably featured in some capacity in nearly every culture), but i think particularly apt is how it links to venus aka. the morning star.

in the interest of keeping this brief (im sure cleverer people may wish to clarify/develop this more!!!), and keeping on track with where its place may sit in the show, i think it's first of all potentially of interest how this building is lit, given the above. we see the shot of the bentley arriving to whickber street in ep1 at night, and this particular shop (?) front is the most brightly lit... might mean nothing, might mean something:

but when the demons descend in ep5, a good portion of them appear out of the mist from that direction; a green mist (green shop?), reflecting the hell vibes we saw in ep1 etc. that being said, when crowley starts sensing Trouble Is Afoot earlier on, he's looking in all directions and certainly we see some demons behind him (in the direction of the dirty donkey) when he confronts this particular little gang of them, so unless some demons started arriving ahead of schedule, they may not have all come through this building:

but. we know from eric that the lift is broken, and the only other routes are the small lift, one at a time, or the stairs. shax obviously arrives in style, but the other demons? taken the stairs. what if this front is that exit onto earth? but just the back stairwell?

there's so many potentially loose threads to weave in here, and im sure i'll come back to this at some point, but felt it was an interesting design choice nonetheless, even if it ultimately means naff all✨

#good omens#i'll come back to this im sure#props meta#thats probably the most accurate tag for the moment

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

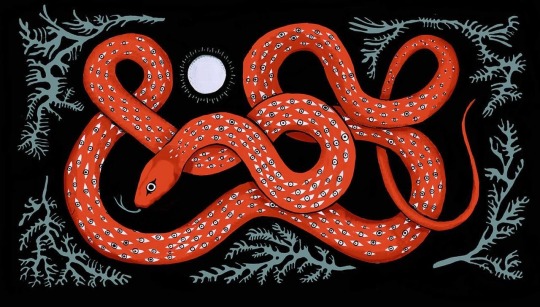

IF YOU KILL A SNAKE - THE SUN WILL CRY

Baltic culture is frequently described as extremely conservative and dedicated to tradition. This is not mere romantic and historical data. For the conservative aspects of the Baltic languages one need look no further than A. Meillet who wrote that: "Le lituanien est remarquable par quelque traits qui donnent une impression d'antiquite indo-europeenne; on y trouve encore au XVIe siecle et jusqu'aujourd'hui des formes qui recouvrent exactement des formes vediques ou homeriques..." (Meillet 1964:73). Secondly, the Baltic peoples (who at one time comprised several related tribes that are now extinct, eg. the Old Prussians) were the last Europeans to adopt Christianity. The new religion was introduced into Latvia and Prussia at the beginning of the thirteenth century by the Knights of the Teutonic Order. The Lithuanians resisted the longest and officially only joined the Christian Church in 1387 through Poland. The new faith, however, was introduced in a foreign language (Polish) and was not understood by the Baltic villagers who remained pagan.

The merger of these two religions commenced in the sixteenth century and continued for three hundred years, the Christian missionaries never entirely destroying the old religion. The final product was a syncretistic religion with only a veneer of Christianity over a surviving core of pagan belief. In this way, the Baits clearly distinguish themselves from their Slavic and Germanic neighbors who accepted Christianity at a much earlier date (the Slavs ca. tenth century, the Germans in the ninth century). As a result, these latter peoples are farther removed from their pagan past and although various folk-beliefs and customs may still exist as "remnants" of their ancient religion, their initial meaning and intent has since become quite obscured. Scholars may sometimes reconstruct plausible explanations for pagan survivals in Germanic and Slavic folk-belief, but the "folk" as such are usually quite unaware and unconcerned about them. In contrast, Baltic peasants in the early twentieth century could often explicate their own folk customs and beliefs in the same manner as their pagan ancestors did several hundred years ago.

A particularly fine example of such long-term persistence of belief from the pagan era to the present is the Balts' attitude towards the snake, a major figure of tale-type 425 M with which this study is concerned.

THE SNAKE

Chronicles, travelogues, ecclesiastical correspondence and other historical records written by foreigners often made mention of snake worship among the Old Prussians, Samogitians, Lithuanians, and Latvians. The snakes were frequently referred to as žalčiai (cognate with Žalias 'green') which has been identified as the non-poisonous Tropodonotus natrix. Sometimes the chronicles also referred to them as gyvatės, a word which is clearly associated with Lith. gyvata 'vitality' and gyvas 'living'. The following historical records should more than suffice to demonstrate that snakes were worshipped widely among the Balts.6

In the eleventh century, Adam of Bremen wrote that the Lithuanians worshipped dragons and flying serpents to whom they even offered human sacrifices (Balys 1948:66).

Aeneas Silvius recorded in 1390 an account given him by the missionary Jerome of Prague who worked among the Lithuanians in the final decade of the fourteenth century. Jerome related that

The first Lithuanians whom I visited were snake worshippers. Every male head of the family kept a snake in the corner of the house to which they would offer food and when it was lying on the hay, they would pray by it.

Jerome issued a decree that all such snakes should be killed and burnt in the public market place. Among the snakes there was one which was much larger that all the others and despite repeated efforts, they were unable to put an end to its life (Balys 1948:66; Korsakas, et al 1963:33).

Dlugosz at the end of the fifteenth century wrote that among the eastern Lithuanians there were special deities in the forms of snakes and it was believed that these snakes were penates Dii (God's messengers). He also recorded that the western Lithuanians worshipped both the gyvatės and žalčiai (Gimbutas 1958:35).

Erasmus Stella in his Antiquitates Borussicae (1518) wrote about the first Old Prussian king, Vidvutas Alanas. Erasmus related that the king was greatly concerned with religion and invited priests from the Sūduviai (another Baltic tribe), who, greatly influenced by their stupid beliefs, taught the Prussians how to worship snakes: for they are loved by the gods and are their messengers. They (the Prussians) fed them in their homes and made offerings to them as household deities (Balys 1948: II 67).

Simon Grunau in 1521 wrote that in honor of the god Patrimpas, a snake was kept in a large vessel covered with a sheaf of hay and that girls would feed it milk (Welsford 1958:421).

works: Balys 1948:66-74; Elisonas 1931:81-90; Gimbutas 1958: 32-35; Korsakas et al 1963:22-24; and Welsford 1958:420-422.

Maletius observed ca. 1550 that...

The Lithuanians and Samogitians kept snakes under their beds or in the corner of their houses where the table usually stood. They worship the snakes as if they were divine beings. At certain times they would invite the snakes to come to the table. The snakes would crawl up on the linen-covered table, taste some food, and then crawl back to their holes. When the snakes crawled away, the people with great joy would first eat from the dish which the snakes had first tasted, believing that the next year would be fortunate. On the other hand, if the snakes did not come to the table when invited or if they did not taste the food, this meant that great misfortune would befall them in the coming year (Balys 1948:67).

In 1557 Zigismund Herberstein wrote about his journey through northwestern Lithuania (Moscovica 1557, Vienna):

Even today one can find many pagan beliefs held by these people, some of whom worship fire, others — trees, and others the sun and the moon. Still others keep their gods at home and these are serpents about three feet long... They have a special time when they feed their gods. In the middle of the house they place some milk and then kneel down on benches. Then the serpents crawl out and hiss at the people engaged geese and the people pray to them with great respect. If some mishap befalls them, they blame themselves for not properly feeding their gods (Balys 1948: II 67).

Strykovsky in his 1582 chronicle on the Old Prussians related:

They have erected to the god Patrimpas a statue and they honor him by taking care of a live snake to whom they feed milk so that it would remain content (Korsakas et. al 1963:23).

A Jesuit missionary's report of 1583 reported:

.. .when we felled their sacred oaks and killed their holy snakes with which the parents and the children had lived together since the cradle, then the pagans would cry that we are defaming their deities, that their gods of the trees, caves, fields, and orchards are destroyed (Balys 1948: 11,68).

In 1604 another Jesuit missionary remarked:

The people have reached such a stage of madness that they believe that deity exists in reptiles. Therefore, they carefully safeguard them, lest someone injure the serpents kept inside their homes. Superstitiously they believe that harm would come to them should anyone show disrespect to these serpents. It sometimes happens that snakes are encountered sucking milk from cows. Some of us occasionally have tried to pull one off, but invariably the farmer would plead in vain to dissuade us... When pleading failed, the man would seize the reptile with his hands and run away to hide it (Gimbutas 1958:33).

In his De Dies Samagitarum of 1615, Johan Lasicci wrote:

Also, just like some household deities, they feed black-colored reptiles which they call gioutos. When these snakes crawl out from the corners of the house and slither up to the food, everyone observes them with fear and respect. If some mishap befalls anyone who worship such reptiles, they explain that they did not treat them properly (Lasickis 1969:25).

Andrius Cellarius in his Descripto Regni Polonicae (1659) observed:

although the Samogitians were christianized in 1386, to this very day they are not free from their paganism, for even now they keep tamed snakes in their houses and show great respect for them, calling them Givoites (Balys 1948: II 70).

T. Arnkiel wrote that ca. 1675 while traveling in Latvia he saw an enormous number of snakes.

die night allein auf dem Felde und im Walde, sondern auch in den Häusern, ja gar in den Betten sich eingefunden, so ich mannigmahl mit Schrecken angesehen. Diese Schlangen thun selten Schaden, wie denn auch niemand unter den Bauern ihren Schaden zufügen wird. Scheint, dass bey denselben die alte Abgötterey noch nicht gäntzlich verloschen (Biezais 1955: 33).

The Balts' positive attitude towards the snake has been recorded also in the late nineteenth century in the Deliciae Prussicae (1871) of Matthaus Pratorius who observed: "Die Begegnung einer Schlange ist den Zamatien und preussischen Littauern noch jetziger Zeit ein gutes Omen (Elisonas 1931:8.3).

Aside from the widespread attestation of snake-worship among the Baits and its persistence into Christian times, these historical records also suggest an intriguing relationship between Baltic mythology and our folk tale. Both Simon Grunau (1521) and Strykovsky (1582) mention the worship of the snake in close reference to the god Patrimpas. This deity is commonly identified as the "God of Waters" and his name is cognate with Old Prussian trumpa 'river'. The close association between the snake and the "God of Waters" has prompted E. Welsford to suggest a slight possibility that the water deity Patrimpas was at one time worshipped in the form of a snake (Welsford 1958:421). A serpent divinity associated with the water finds numerous parallels among Indo-European peoples, eg. the Indie Vrtra who withholds the waters and his benevolent counterpart, the Ahibudhnya 'the serpent of the deep'; the Midgard serpent of Norse mythology; Poseidon's serpents who are sent out of the sea to slay Lacoon, etc. A detailed comparison of the IE water-snake figure would far exceed the limits of this paper, nevertheless, it is curious to note that except for the quite minor Ahibudhnya, most IE mythologies present the water-serpent as malevolent creature — an attitude quite at variance with that of the ancient Balts.

From the historical records it is difficult to determine to what extent the ancient Balts might actually have possessed an organized snake-cult. Erasmus Stella's account of 1518 concerning the Sudovian Priest's introduction of snake-worship into Prussia might suggest such an established cult. In any event, that the snake was worshipped widely on a domestic level cannot be denied. In general it was deemed fortunate to come across a žaltys, and encountering a snake prophesied either marriage or birth. The žaltys was always said to bring happiness and prosperity, ensuring the fertility of the soil and the increase of the family. Up until the twentieth century, in many parts of Lithuania, farm women would leave milk in shallow pans in their yards for the žalčiai. This, they explained, helped to ensure the well-being of the family.

In 1924 H. Bertuleit wrote that the Samogitian peasants "even at the present time, staunchly maintain that the žaltys/gyvatė is a health and strength giving being" (Balys 1948: II 73). To this day in Lithuania, the gabled roofs are occasionally topped with serpent-shaped carvings in order to protect the household from evil powers.

The best proof of the still persistent respect, if no longer veneration, of the snake (or žaltys in specific) is provided by various folk sayings and beliefs which were recorded during this century. Some of them clearly reflect the association of the snake with good luck, while others depict the evil consequences which will befall one if he does not respect the snake. The following are some examples:7

Good luck

1. If a snake crosses over your path you will have good luck.

2. If a snake runs across your path, there will be good fortune.

3. Žaltys is a good guardian of the home, he protects the home from thunder, sickness and murder.

4. If a žaltys appears in the living room, someone in that house will soon get married.

Bad consequences

5. In some houses there live domestic snakes; one must never kill this house-snake, for if you do, misfortunes and bad luck will fall on you and will last for seven years.

6. If you burn a snake in a fire and look at it when it is burning, you will become blind.

7. If you find a snake and throw it on an ant hill, it will stick out its little legs which will cause you to go blind.

8. If s snake bites someone and the person then kills the snake, he will never get well.

9. If a snake bites a man and another person kills it, the man will never recover.

10. If you kill the snake that bit you, you will never recover.

11. If a žaltys comes when one is eating, one must give it food, otherwise one will choke.

12. When children are eating and a žaltys crawls up to them, he must be fed; otherwise the children will choke.

13. If you kill a žaltys, your own animals will never obey you.

14. If someone kills a snake, it will not die until the sun has set.

15. If you kill a snake, the sun cries.

16. If you kill a snake and leave it unburied, the sun grows sick.

17. When a snake or a žaltys is killed, the sun cries while the Devil laughs.

18. If you kill a snake and leave it in the forest, then the sun grows dim for two or three days.

19. If you kill a snake and leave it unburied, then the sun will cry when it sees such a horrible thing.

20. If you kill a snake, you must bury it, otherwise the sun will cry when it sees the dead snake.

The snake's name.

21. If one finds a snake in the forest and wants to show it to others, he must say: "Come, here I found a paukštyte (little bird)!", otherwise, if you call it a gyvate, the snake will understand its name and run away.

22. If you see a snake, call it a little bird; then it will not attack humans.

23. While eating, never talk about a snake or you will meet it when going through the forest.

24. Snakes never bite those who do not mention their name in vain, especially while eating and on the days of the Blessed Mary (Wednesdays and Sundays).

25. On seeing a snake you should say: "Pretty little swallow." It likes this name and does not get angry nor bite.

26. If someone guesses the names of a snake's children, the snake and its children will die.

27. If you do not want a snake to bite you when you are walking though the forest, then don't mention its name.

28. A snake does not run away from -those who know its name.

29. Whoever knows the name of the king of the snakes will never be bitten by them.

30. One must never directly address a snake as gyvatė (snake); instead, one should use ilgoji (the long one) or margoji (the dappled one).

Snakes and cows.

31. Every cow has her own žaltys and when the žaltys becomes lost, she gives less milk. When buying a cow, a žaltys should also be bought together.

32. If you kill a žaltys, things will go bad because other žalčiai will suck all the milk from the cows.

Life-index and affinity to man

33. Some people keep a žaltys in the corner of their house and say: if I didn't have that žaltys, I would die.

34. If a person takes a žaltys out of the house — that person will also have to leave home.

35. If a žaltys leaves the house, someone in that household will die.

Enticement.

36. When you see a snake crawl into a tree trunk, cross two branches and carry them around the tree stump. Then place the crossed branches on the hole through which the snake crawled in. When the sun rises, you will find the snake lying on these branches.

37. When you see a snake and it crawls into a tree-stump, take a stick and draw a circle around the stump. Then, break the stick and place it in the shape of a cross and the snake will crawl out and lie down on the cross.

Miscellaneous.

38. If a snake bites you, pick it up in your hands and rub its head against the wound. Then you will get well.

39. When one is bitten by a snake, say: "Iron one! Cold-tailed one! Forgive (name of person bitten)," while blowing in the direction of the sick person.

40. If you throw a dead snake into water, it will come back to life.

41. A snake attacks a man only when it sees his shadow.

42. They say that when a snake is killed, it comes back to life on the ninth day.

43. If a snake bites an ash tree, the tree bursts into leaf.8

44. If someone understands the language of the snakes, whey will obey him and he can command them to go from one place to another.

45. If there are too many snakes and you want them to leave, light a holy fire at the edge of your field and in the center; all the snakes will then crawl in groups through the fire and go away, but you must not touch them.

Some folk-beliefs show an obvious Christian influence and are possibly the products of frustrated Jesuit anti-snake propagandists:

45. When you meet a snake you must certainly have to kill it for if you fail to do so, then you will have committed a great sin.

46. If you kill a snake, you will win many indulgences.

47. If you kill seven snakes, all your sins will be forgiven.

48. If you kill seven snakes, you will win the Kingdom of Heaven

Such examples as these, however, are quite rare in comparison to the folk-beliefs which are sympathetic to the snake.

Considering the evidence amassed from both historical records and folk-belief that the Balts possessed a positive and reverent attitude towards the snake, it is little wonder that the snake husband's death is viewed as tragedy. If, as the proverbs suggest, a snake's death can affect the sun, then what consequences might the death of the very King of the Snakes have among mortals? This tragic outcome, as Swahn has indicated, gives the tale a character which is foreign to the true folk-tale (Swahn 1955:341). This tale could not terminate on the usual euphoric note typical of the Märchen (although the tale does contain numerous Märchen motifs) because the main event of the story relates to a "reality" which the people who tell the story still hold to be true. The tale is thus well-nourished in a setting where such folk-beliefs about the snake persist. On the other hand, the tale itself may have played a part in affecting the longevity of the beliefs. Whichever case may be true, it is obvious that both are closely related.

A specific element of folk-belief that survived as an ideological support to the tale is that of the snake's name-taboo. The tragic killing of the snake king is implemented only because the name formula is revealed. Thus, the general snake-taboo proverbs (No. 21-30; receive a specific denouement in the snake-father ordering that his name and summoning formula not be revealed to others. There appear to be two important aspects that surround this name-taboo. First of all, it reflects the primitive concept of one being able to manipulate another when his name is known. A second aspect is that the name-taboo may rest on the reverence and fear of a more powerful supernatural being that requires mortals never to mention the deity's real name. For example, Perkūnas, the all-powerful Thunder God of the Balts, has many substitutes for his real name which are usually onomatopoeic with the sound of thunder, eg. Dudulis, Dundulis, Tarškulis, Trenktinis. In our tale the general reason for the name-taboo may be partially related to this second explanation especially since there are a number of variants for the name of the snake-king, eg. Žilvine, which have no etymological support but bear a suspicious resemblance to the word žaltys 'snake'. This might then indicate a deliberate attempt to destroy the name žaltys in such a way as to avoid breaking the name-taboo but still retain some of the underlying semantic force. On the other hand, it must be admitted that many of the summoning formulas include a direct reference to the husband as žaltys. In these cases, since the brothers know his name, they can extend their power over him. It is likely that both these aspects should be considered when explaining the name-taboo of the story. The clear distinction between the obviously Christian folk-sayings (No. 45-48) and the underlying pro-snake proverbs carries considerable significance when one views the substitution of the Devil for the snake in many of the Latvian variants. This substitution occurred in all probability with the increasing influence of Christianity and its usual association of the serpent with the Devil as in the Garden of Eden story. It is interesting to reflect that in some cases the entire story proceeds with the same tragic development despite this substitution (Lat. 2, 7, 9, 15). Even in the Lithuanian variant (Lith. 4) where an old woman tells the heroine that her snake-husband is actually the Devil, this does little to alter the tragic tone of the tale's ending. Thus, it would seem that the Devil is a relatively late introduction, sometimes amounting to little more than a Christian gloss of the snake's real identity. On this basis, one might well conelude that the tale must have been composed in pagan times and is thereby, at the very least, four or five centuries old if not far older.

The effect of the diabolization of the snake among the Latvian variants seems to have led to a disintegration of the tale's actual structure. In some of the Latvian redactions (Lat. 4, 8, 15) where the Devil is the abductor, the story simply ends with the killing of the supernatural husband and the heroine's rescue. In variants of the tale which progress with such a rescue-motif development, it is important to observe that many of the other elements are consequently dropped. There is no name-taboo or magic formula, sometimes no children, and, of course, no magical transformation. Thus the tale is stripped of all these other embellishments and appears rather bare. It simply relates an abduction of the heroine and her rescue, usually accomplished by some members of her family or a priest and thunder storm (Latv. 15). In any event, the abductor is one whom she quite definitely cannot marry and therefore, there can be no Märchen marriage-feast. When the tale has been altered, the rescue motif can then be correlated to the other Märchen tale-types where the heroine is abducted (rather than married) and is eventually rescued by an eligible marriage partner. One might even speculate that this will be the eventual fate of those particular Latvian variants which no longer specify that the snake, a sacred and positive being, is the supernatural husband. We then have an intimate relationship between folk-belief and folk-tale which ultimately may be mirrored in the very structure of the story.

The place of the snake in Baltic folk-belief and its relation to our tale now having been well established, the obvious next question is whether similar beliefs exist in the neighboring non-Baltic countries and, if not, might we propose this as a possible explanation why the story as a Baltic oicotype has not spread to these other cultures. A complete analysis of the role of the snake in Germanic and Slavic folk-belief would far exceed the time allotted for the composition of this study, nevertheless, some of the evidence arrived at by way of a cursory review should be brought forth.

Of sole interest in our investigation of snake beliefs among the Germans and Slavs is the extent to which these cultures parallel the Balts with respect to the lat-ter's quite sympathetic attitude toward the snake. Bolte and Polivka, Hoffmann - Krayer and J. Grimm all mention that among the Germans there are some beliefs which view the snake in a positive light. A few specific entries in Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens are similar to some folk-beliefs already cited among the Balts (Hoffmann - Krayer 1935-36: VII 1139-1141). Bolte and Polivka in listing parallels to Grimm's Märchen von der Unke cite several instances of snakes bringing great fortune to those who treat them well and disaster to those who disrespect or abuse them (Bolte and Polivka 1915: II 459-465) .9 Both Hoffmann-Krayer and Grimm, after listing various "remnants" of what they maintain might be evidence for an ancient snake-cult in Germany, state that under the influence of Christianity the snake is usually diabolized and its image as a malignant and deceitful creature predominates. Only in some very "old" stories are there traces of the original heathen positive attitude towards the snake (Grimm 1966: II 684); Hoffmann - Krayer 1935-36: VII Sp. 1139).

Welsford, in writings about the snake-cult among the ancient Slavs, states that it was probably quite similar to the one which persisted among the Baits, but that the latter seems to have retained it much longer. In the Slavic countries the snake was usually regarded as a creature in which dead souls were embodied and through time came to be viewed mostly as a dangerous animal. It is this aspect of the snake which appears most often in Slavic stories. The snake seems to be similar or even identical with other evil antagonists such as Baba Yaga (Welsford 1958: 422). There are also many stories involving a hero or heroine who has been transformed into a snake by evil enchantment.10 These stories primarily relate how this "curse" is ultimately overcome.

These remarks indicate that the respect for the snake and its association with good fortune was also known to both Germans and Slavs. The heathen past, however, is farther removed from these peoples than form the Latvians and Lithuanians. If similar snake-cults existed in Germany and in Slavic lands, they were not practiced on the same scale within recorded history as they were by the Baits. The cited fourteenth to eighteenth century reports on the Baits were written by Slavs and Germans and already then the surprise and disgust with which they viewed Baltic snake-veneration gives us a good indication of the place of the snake within their own cultures.

Cursory perusal of present-day Germanic and Slavic beliefs about the snake seems to verify the fact that, indeed, the snake is usually considered deceitful and malevolent. The majority of folk-beliefs, expressions, and proverbs reflect this general negative attitude. There are only a few examples of a positive regard for the snake, usually associating it with powers of healing. One may speculate that the folk medicine beliefs which prescribe the use of a snake as an effective cure may be partially explained by the notion that evil conquers evil (ie. an extension of similia similibus curantor). This, however, is mere speculation for it is also likely that the snake's obvious vitality may be responsible for its specification in various folk cures. This latter case seems to be well supported in the Baltic beliefs (cf. folk-belief 38, 39) since the name for snake, gyvatė, and its association with gyvata 'life' helps one to consciously sense the logical correlation.

Stories which mention the affinity between snakes and children are probably known throughout the world because they describe an unexpected occurrence. W. Hand has suggested that the credibility of such stories rests on the notion that the child's innocence and helplessness can not be breached even by a snake (Hand 1968). Note that this kind of logic presupposes that the snake is evil.

Hence, although a more thorough investigation is definitely required, one may still suggest that the Baits have sustained through their history a more sympathetic regard for the snake than either the Germans or Slavs. Assuming that this hypothesis may be true, let us now see how it might be related to the discussion of our tale.

When one assumes no comparable folkloric basis among the Germans and Slavs with regard to the snake, then the Baltic tale would make very little "cultural sense" to these people and even if it penetrated into their cultural spheres, it would probably by altered by the same process which seems to be occurring with the Latvian tales. Secondly, even if we posit the existence of a similar positive attitude toward the snake in these cultures at a pre-Christian time, these beliefs would now seem to have almost entirely died out. In any case, even though there may be some survivals, there has been no comparative retention of respect and reverence for the snake among the Germans and Slavs as one finds with the Baits. The narrative motif of this tale clearly rests on a folk-belief which serves as an ideological backbone to the story. Conversely, people unfamiliar with the underlying folk-belief or possessing quite antithetical beliefs would find this tale lacking in cultural meaning and, therefore, "untransferable," at least in its original form.

TREES

Another typical element of the Baltic 425 M tale is the terminating motif where the heroine and her children are transformed into trees. Swahn has commented that it is this motif which gives the tale the character of an aition-legend (Swahn 1955: 341). However, most Baltic aetiological-legends rarely possess such fantastic Märchen-type motifs as a supernatural husband, difficult tasks or name taboo and are certainly not so elaborate or complex as this specific tale. The explanation for the curse-inflicted transformation is based in Baltic folk-beliefs. First of all, the power of the heroine's word is what brings about the arboreal transformation. To this very day the Balts believe that a parent's curse is most effective in bringing about dire consequences to her children. This belief is, of course, also well known in other cultures. Secondly, one can observe that the transformation into trees is typically Baltic. The full impact of this motif to the Baits is directly related to their folk-beliefs and is not simply an element of the story to be appreciated on an aesthetic basis. The Balts have retained to this very day a special empathy for trees. They believe that trees are like humans in that they also have a heart and blood (sap). When cut down without good reason, they feel pain and there are folk accounts of how real blood has flowed out of injured trees. For this reason, parents always instruct their children (as this writer was instructed) never to pluck leaves, break the branches or peel the bark from a tree since it experiences the same kind of pain as when someone pulls the hair of one's head or peels off his skin from his body. Whoever injures a tree in such a manner will eventually have to suffer a similar pain in his own life. Trees also have a language of their own which man is unable to understand. One can, however, hear a tree cry and moan every time an axe digs into its trunk by putting his ear to the tree-trunk.

All these current beliefs stem from a conviction rooted in the pagan era that the souls of the dead actually go into trees, usually the ones growing near a person's homestead or more specifically, near his grave. For this reason, trees in cemeteries are considered especially sacred and must never be touched by a pruner's hand since "to cut a cemetery tree is to do evil to the deceased" (Gimbutas 1963: 191). This belief in total reincarnation of one's life force in a tree has been slightly altered by the influence of Christianity. It is quite commonly heard that souls which must undergo penance for their sins are sent by God into trees. Thus, when a tree creaks on a windless night, it is in truth the weeping and crying of the penitent soul that one hears. One must then pray for them, mentioning Adam and Eve, and the soul will be pardoned and the tree will cease its creaking. It is said that souls in general inhabit old spruces, but more specifically, a girl's soul will pass into a linden or a birch while a man's soul will enter an oak, ash or alder. In general, all trees are holy save the aspen which is believed cursed because it was on that tree that Judas hung himself. This is directly related to our tale where the youngest daughter, the one who betrayed her father, is especially cursed and transformed into an aspen.

Another proof linking reincarnation with trees is found in the funeral laments which have served as a reservoir of on-going folk-belief up until this present century, In one, a mother addresses her dead daughter:

What kind of flower will you bloom in? What kind of leaf? What blossoms will you sprout when I walk by? How will I recognize you? How will I know you? Will you be in flowers? In leaves? (Šalčiūtė 1967:42).

A daughter cries for her mother:

.. .I will ask my brother that he would plant a birch on my mother's grave. When the cold storms will come, I shall go up the high hill to my mother's grave. The birch branches will enfold me like my mother's white arms. The north wind will not blow on me, the biting rain will not fall on me (Jonynas et al 1954: 522).

A daughter cries for her father:

Oh that a green plane-tree would grow from my father's grave. All the beautiful birds would then alight there, and would pick sweet berries. Oh, a mottled cuckoo would weep for you with her song (ibid.:52B).

And a mother laments for her. daughter:

Oh my dearest little daughter, Oh, how will you sleep in the black earth where the winds don't blow, where the sun doesn't shine. Only the cuckoo will cry. Only the little birds will sing in the white birch on your little grave! (ibid.:533).

Other than laments, many Lithuanian folksongs draw analogies between man and trees or plants. The usual epithet for a young girl is "white lily" and for a young lad it is "white clover." Constant parallels are also drawn between a young maid and a green linden and a young man and a green oak. As folksong scholars have marked, this type of parallelism usually enhances the songs' poetical quality and these traditional "formulaic expressions" may have persisted precisely because of their aesthetic appeal. Nevertheless, they seem to be instrumental in shaping the general world-view of the people who sing them and it is, therefore, not at all surprising that the Baits do feel this close identity with nature. The following Lithuanian folksong well illustrates this:

Oh dearest father, don't cut the birch growing near the road.

Oh my own true mother, don't fetch the water from the stream.

Oh my own true brother, don't cut the hay near the water.

Oh my own true sister, don't pluck the flowers in your garden.

The birch near the road is really me, the young one.

The water from the stream — my sorrowful tears.

The hay near the waters — my yellow hair.

The flowers in the garden — my bright little eyes.

(Balys 1948: II 64).

CUCKOO

It is interesting to observe that in many Baltic folktales, legends, songs and beliefs, women turn into cuckoos out of grief when they have been separated from ones they love. This motif constantly repeats itself in the laments where the mourner expresses a desire to turn into a cuckoo and "weep with its song." This belief is clearly reflected in those variants of the tale where the heroine becomes a cuckoo and her children become either trees or other birds.

Any attempt to demonstrate that the tale is a Baltic oicotype because of its close correlation to Baltic folk-beliefs becomes more difficult when dealing with these other motifs of the story. The power of a parent's curse, the transformation to some other form of plant or animal out of grief, even the idea of reincarnation in trees are not solely unique to the Baits but are found in other European folk traditions. What may be somewhat atypical is that among the Baits these beliefs are still widespread and constantly expressed to this very day and find reinforcement in songs and laments. It may then be argued that all of these factors help to imbue the story with a cultural relevance for the Balt which might not be so quickly perceived or deeply felt by a German or Slav. But it must be admitted that the case for these motifs, ie. trees, cuckoo, is not nearly so strong as that for the snake when discussing possible factors that would have limited the tale to the Baltic countries.

CONCLUSION

One conclusion that can certainly be drawn is that the motifs of the tale and their ultimate structure (ie. sequence of events) reflects many still very viable folk-beliefs which are generally known to most Baits. This would almost suggest that the tale is not as fantastical as it would first seem since it is so deeply rooted in a folkloric reality accepted by the people who relate it. Whether the story should therefore be considered a Sage rather than a Märchen (its usual classification by folktale scholars) is another matter.

The initial purpose of this study — to illustrate how folk-beliefs may be the laws which account for oicoty-pification of a folk tale — has been partially fulfilled. If one of the "laws" which affect the life of a story is the relevance which it may have for the people via various folk-beliefs and convictions, then that case has been well demonstrated. But whether this relevance simply enhances the popularity of the tale or is actually the crucial life-root which maintains the existence of the tale and restricts its migration requires much more substantial proof. If our analysis of the disintegration of some of the Latvian variants is valid and the general discussion of the folk motifs, especially the snake, is also of some merit, then perhaps our research is at least heading in the right direction.

🐍🐍🐍

Folktale Type 425-M: A Study in Oicotype and Folk Belief - Elena Bradunas

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 21, No.1 - Spring 1975

Editors of this issue: Antanas Klimas, Thomas Remeikis, Bronius Vaškelis

Copyright © 1975 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Lituanus

"IF YOU KILL A SNAKE — THE SUN WILL CRY"

Folktale Type 425-M

A Study in Oicotype and Folk Belief

ELENA BRADŪNAS

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Werewolf in Latvian Myth, Legend, and Folk Beliefs

Latvian folklore is rich with mythical creatures and spirits, and one of the most prominent and intriguing figures in its mythology is the werewolf or vilkatis. The concept of the werewolf appears across various Baltic and Northern European traditions, often linked to ideas of transformation, liminality, and shamanistic practices. In Latvia, the werewolf carries a mix of fear, reverence, and symbolic meaning, reflecting the deeper cultural beliefs about nature, humanity, and the supernatural.

The Werewolf in Latvian Folklore The Latvian word vilkatis combines vilks, meaning "wolf", and vīrs or ats, implying "man" or "creature." In Latvian myth, a vilkatis is a person who can transform into a wolf, either by their own will or due to external curses or forces. Unlike the popular Western image of the werewolf as a bloodthirsty monster, the Latvian werewolf embodies more nuanced roles. Sometimes, the transformation is voluntary and linked to magical or shamanistic practices, while in other cases, it is a curse or punishment.

In Latvian legends, vilkatis is portrayed as both a victim and a perpetrator. Some tales describe them as people who have been cursed to become wolves, forced to roam the forests and live apart from society. Others depict them as people who willingly transform into wolves, often for the sake of accomplishing a difficult or dangerous task, such as hunting or avenging wrongdoings. The vilkatis could also serve as a protector of the village, chasing away evil spirits or guarding livestock.

Transformation and Curses The transformation into a werewolf in Latvian tradition could be caused by several factors. One of the most common ways a person could become a vilkatis was by breaking a taboo or engaging in a forbidden act. Some stories mention specific rituals or the consumption of certain magical herbs that allow the transformation. In some cases, the curse is hereditary, passed down from generation to generation, which ties the werewolf myth to broader themes of ancestral sin or familial curses.

One of the more benevolent interpretations of the vilkatis sees them as individuals cursed by witches or sorcerers. They might be condemned to wander as wolves for a set period—seven or nine years—or until a specific task is fulfilled. In such cases, the curse often ends when someone recognizes the werewolf, usually through some distinguishing mark or behavior, and shows them kindness, thereby breaking the spell.

Symbolism and Cultural Significance The figure of the vilkatis in Latvian culture holds a complex symbolic significance. It represents the boundary between the human and animal worlds, symbolizing a liminal state where one is neither fully human nor fully beast. This transformation reflects ancient shamanistic traditions, where entering an animal's form was seen as a way to connect with nature's primal forces or gain special powers.

Moreover, the werewolf myth reflects the fears and anxieties of rural life. Wolves were common in the forests of Latvia and posed a real threat to livestock and sometimes even humans. The vilkatis may have originated as a way to personify this fear, giving the predator a more human form that people could understand or confront.

In other interpretations, the vilkatis represents a person alienated from society, someone who lives on the outskirts of civilization due to their magical abilities, curses, or social transgressions. As such, the werewolf can be seen as a symbol of the outsider, someone who exists outside the accepted norms of behavior but still plays an essential role in the community by keeping dangerous forces at bay.

The Werewolf in Latvian Beliefs and Traditions Folk beliefs about werewolves persisted in Latvia well into the 19th and even the early 20th centuries. Local people believed that encountering a vilkatis could bring both good fortune and misfortune, depending on the circumstances. In some regions, people would leave offerings at crossroads or in the forest to appease werewolves or protect themselves from transformation. Conversely, stories tell of hunters or village folk confronting werewolves, usually by recognizing the human behind the wolf and either helping them return to their human form or, in darker tales, killing the creature to lift the curse.

The image of the werewolf in Latvian folk beliefs also became intertwined with Christian morality. Some stories associate the vilkatis with demonic forces or as punishment for immoral behavior, reflecting the church's influence on Baltic pagan traditions. Yet, in many cases, the werewolf remains a neutral or even positive figure, one who can straddle both worlds and bring balance to the community.

Conclusion The werewolf in Latvian myth, legend, and folk belief is a multifaceted figure that reflects the deep connection between humans, nature, and the supernatural in Latvian culture. The vilkatis is not merely a monstrous villain but often a complex character whose story reflects the moral, social, and environmental tensions of the time. As such, the Latvian werewolf embodies a rich tradition of storytelling that continues to fascinate and inspire with its layers of meaning and cultural significance.

Personal Note:

When I was a very young child and my elderly grandmother was staying over at our place, she would frequently tuck me in for the night. Grandmom made it a priority to draw the curtains to my window closed on full moonlights. With the clear expression of concern and yes even fear on her face when rays of the moon fell on my bed.

She'd sit down on the edge of the bed and tell me stories of the old Latvian god Vilks (today the general Latvian word for 'wolf') a god of the deep wilds of the forest. Who had once been a Latvian Warrior but learned the power of shapeshifting by way of magick. During a time of invasion he taught this skill to his fellow people and with it, they defeated all foes. Being a shapeshifting werewolf and hero had it's downside. Eventually, your humanity would fade. And you would become a Feral Wolf of Deep Forest.

Grandmom and later Mom made it a point to draw the curtains closed on full moons. For to sleep in moon beams upon the bed. It was the first process of becoming Vilks eventually. Becoming a Feral Werewolf.

Just as soon and Grandmom and Mom would leave. I hopped out of bed and flung those curtains wide open as well as the window!

Hooooooooooowwwwwwwwwlllllll!

0 notes

Text

According to Latvian folk legends, the Easter Bunny was once a mythical creature known as "Lieldienas kaza" or "Easter goat" in English. This goat-like figure was said to bring springtime fertility and abundance to the land.

In ancient Latvia, top-hats were worn by farmers as a symbol of wealth and fertility. The tall, pointed shape of the top-hat was believed to represent the horns of the Easter goat, and therefore, it became associated with the holiday.

As Christian traditions spread to Latvia, the Easter goat gradually transformed into the Easter Bunny. However, the top-hat remained a staple accessory for this beloved holiday figure.

In addition to its symbolic meaning, the top-hat also serves a practical purpose for the Easter Bunny. In Latvia, where winters are harsh and snowy, a top-hat helps to keep the bunny's ears warm and protected from the elements while delivering Easter eggs.

Moreover, the color of the top-hat is significant in Latvian culture. In many old Latvian tales, the Easter goat or bunny is described as wearing a red top-hat. Red holds great significance in Latvian culture, representing vitality, strength, and good luck. This is why many Latvians still choose to decorate their homes with red Easter eggs.

But why specifically a top-hat, rather than any other headwear? This is believed to be because of the resemblance between the shape of a top-hat and the traditional Latvian headdress, the "Kokles lielauksta cepure," which is also tall and pointed.

Though many countries have their own version of the Easter Bunny, the tradition of wearing top-hats can be traced back to Latvia and its rich cultural heritage. Today, Latvians continue to celebrate Easter with colorful eggs, traditional foods, and of course, the iconic top-hat-wearing Easter Bunny. So, if you happen to spot a bunny wearing a top-hat this Easter, you'll know it's a nod to Latvian tradition and folklore.

0 notes

Text

Latvian Heritage Unveiled: Why Choosing the Riga - Rēzekne Bus is Your Gateway to Discovery

Embarking on a journey from Riga to Rēzekne by bus is akin to opening a treasure chest of Latvian heritage and culture. This route, bridging the vibrant capital with the serene eastern gem, serves not just as a travel path but as a gateway to discovery. The Rīga Rēzekne autobuss experience offers an immersive dive into Latvia's heart, unveiling its history, landscapes, and the spirit of its people. Let's embark on this journey together, uncovering why this route is your ticket to an enriching exploration of Latvian heritage.

A Journey Through Time: The Historical Path

Traveling from Riga to Rēzekne is like leafing through the pages of a history book. Each town and village along the way has a story, from ancient battles to the struggle for independence, offering a unique glimpse into Latvia's past.

Cultural Mosaic: The Diversity of the Route

This journey is a celebration of diversity, showcasing the blend of cultures that make up Latvia. The Rīga Rēzekne autobuss route passes through areas inhabited by a rich tapestry of ethnic groups, each contributing to the country's unique cultural identity.

Natural Landscapes: Window to Latvia's Soul

The route offers mesmerizing views of Latvia's untouched natural beauty. From dense forests to tranquil lakes, the changing landscapes provide a backdrop that captivates and inspires, inviting travelers to connect with nature.

Rēzekne: The Cultural Heart of Latgale

Rēzekne, known as the heart of the Latgale region, is a beacon of cultural and historical significance. The city's museums, galleries, and monuments are testimonies to the enduring spirit of the Latgalian people.

The Bus Experience: Comfort and Connection

Choosing the bus for this journey means experiencing the warmth of Latvian hospitality. Modern amenities and friendly service ensure a comfortable trip, allowing travelers to relax and soak in the scenery.

Architectural Marvels Along the Way

The route is dotted with architectural gems, from Riga's art nouveau buildings to Rēzekne's sacred sites. Each structure tells a tale, reflecting the artistic and spiritual journey of the Latvian people.

Local Cuisine: A Taste of Latvia

Sampling local cuisine is an integral part of the travel experience. The journey offers numerous opportunities to indulge in traditional Latvian dishes, each a delicious expression of the country's rich agricultural heritage.

Festivals and Traditions: The Living Heritage

Latvia's calendar is filled with festivals and traditions that breathe life into its cultural heritage. Traveling during these vibrant celebrations offers a unique insight into the joy and communal spirit of the Latvian people.

Art and Music: The Pulse of Latvian Culture

The journey from Riga to Rēzekne is a melody of visual and auditory experiences. From street art in urban centers to folk music in rural towns, the route reverberates with the creative pulse of the nation.

Craftsmanship and Creativity: Handmade Latvia

Latvia's rich tradition of craftsmanship is visible throughout the journey. Handmade textiles, pottery, and woodworking showcase the skill and creativity of local artisans, making for unique souvenirs and gifts.

Eco-Tourism and Conservation Efforts

Travelers on this route will witness Latvia's commitment to eco-tourism and conservation. Protected natural parks and sustainable tourism initiatives highlight the country's dedication to preserving its environmental heritage.

Community and Hospitality: The Latvian Way

The warmth and hospitality of the Latvian people shine brightest when traveling by bus. Conversations with locals and fellow travelers can turn a simple journey into an unforgettable experience of community and friendship.

Planning Your Trip: Practical Tips

Planning is key to a seamless travel experience. From booking tickets in advance to packing essentials for the journey, a little preparation goes a long way in making your trip enjoyable and stress-free.

Conclusion: The Journey Begins

Choosing the Rīga Rēzekne autobuss as your gateway to discovery is more than a travel decision; it's an embrace of Latvia's heritage, culture, and natural beauty. This journey is an invitation to explore, learn, and connect with the soul of Latvia. As you embark on this adventure, remember that the true beauty of travel lies not in the destination but in the stories, connections, and memories you create along the way. Welcome to Latvia—your journey of discovery begins now.

1 note

·

View note

Text

03.02. 21:35 | Ilo Pisara vs Latvian Dogs 12 - 5

Ladies and gentlemen, gather 'round as I regale you with the tale of Ilo Pisara's latest hockey odyssey—a saga where our heroes trounced the Latvian Dogs 12-5 in a display that would make even the gods pause their celestial bickering to watch. First off, Teppo Winnipeg transformed into an offensive juggernaut, scoring four goals with the finesse of a master chef slicing through butter—his defense rating notwithstanding because who needs defense when you're busy engraving your name on the puck? Then there's Sami Noddy, embodying "grind" so well we might just start calling him Coffee Bean! Despite treating giveaways like Oprah ("You get a puck! And YOU get a puck!") his contributions were undeniable. Yuri Tarde in goal... Well, let’s say if saving was money management—he’d be filing for bankruptcy. But hey, everyone has off days; maybe he thought it was dodgeball? And Jordan NHL? The man turned center ice into his personal dance floor—scoring six times and proving faceoffs are merely formalities before he starts celebrating. After previous games had us gifting pucks like they were going out of style and aiming shots as if trying to find Narnia beyond the netting—it seems we've found our groove again. Onward Ilo Pisara—to more victories or at least performances that don't have us questioning if our sticks are cursed! Truly folks, what can’t this team do (aside from Yuri playing dodgeball mid-game)?

0 notes

Text

[ad_1] Thus spoke two survivors of Operation Priboi, the code identify for the compelled deportation by way of the Soviet government of greater than 40,000 Latvian males, ladies and kids on March 25, 1949.The ones nightmarish reminiscences may additionally have issued from the tens of 1000's of Estonians and Lithuanians who had been likewise swept up that day by way of flying squadrons of Soviet troops and dispatched to Siberia. A complete of half-a-million citizens of the 3 Baltic states had been deported between 1941 and 1952.Tale continues beneath commercialNow, in gentle of stories of an identical habits by way of Russian troops within the newly occupied territories of Ukraine, the peoples of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, together with the surviving deportees and their households, are reliving that nightmare.“It's unconscionable for Russia to power Ukrainian electorate into Russia and put them in what's going to principally be focus and prisoner camps,” Linda Thomas-Greenfield, U.S. ambassador to the United Countries, informed CNN, noting that she may now not verify the common studies of 1000's of other folks being taken in opposition to their will from the besieged port town of Mariupol.Assuming the studies are true, Russia could be in violation of world regulation, specifically the Geneva Conventions governing the remedy of civilians in wartime. Survivors of the sooner Baltic abductions don't have any hassle believing the studies.Tale continues beneath commercialThe truth that they coincide with remaining week’s regionwide commemoration of the mass deportations of March 25, 1949, makes the scoop the entire extra haunting.“Lately, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania are commemorating the sufferers of mass deportations effected by way of the Communists,” Latvian International Minister Edgars Rinkevics mentioned remaining week, prior to becoming a member of the yearly commemoration of the March genocide, because it is named right here, by way of laying a wreath on the Freedom Monument in Riga. “Provide-day Russia commits crimes in opposition to humanity in Ukraine.”“We Baltic persons are neatly conscious about what Chekists are in a position to,” Rinkevics persisted, the usage of the identify of the unique Soviet secret provider, which performed the primary wave of deportations within the Forties, along side their indigenous communist collaborators.“The process and the mentality” of the Russian profession troops “are the similar,” agreed Karen Jagodin, director of the Museum of Occupations and Freedom in Tallinn, Estonia.Tale continues beneath commercial“I don’t assume any individual who hasn’t lived via the similar factor of their nation’s historical past can perceive what the present occasions in Ukraine unsleeping in us,” she added.“It is extremely unhappy,” concurred Milda Jarusaitine, senior museologist on the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Opponents in Vilnius, Lithuania, “however we will be able to see many parallels between what is occurring then and now.”Actually, the Soviets undertook two mass deportations from the Baltics, one in 1941, after the usS.R. occupied the area in the beginning of International Struggle II, however in 1949, 5 years after Moscow reoccupied the 3 neighboring international locations after defeating the Germans, who had occupied the 3 nations in the meanwhile. The target of the primary expulsion, which came about at the evening of June 14, 1941 — not up to a 12 months after Moscow first occupied the Baltics and per week prior to Nazi Germany attacked the usS.R. — used to be mainly political, aimed toward purging the area of anti-Soviet forces.Tale continues beneath commercialLots of the estimated 60,000 Latvian, Estonian and Lithuanian “enemies of the folks” who had been swept up in that lightning operation and herded aboard Siberia-bound railway wagons had been the lads of the Baltic elite, together with educators, writers, legal professionals and different pros, along side their households.

Greater than 10 p.c had been Jewish; that expulsion might be thought to be the primary section of the Baltic Holocaust, which in the long run noticed the digital extermination of the Jewish inhabitants within the Baltics after the Germans kicked the Soviets out.All through the operation, the lads had been separated from ladies and kids and despatched to laborious hard work or jail camps, the place an estimated 50 p.c had been shot or died on account of the horrific prerequisites, whilst the ladies and kids had been despatched to farms.Operation Priboi, the 1949 deportation, used to be even broader in scope. Its fundamental goal used to be to conquer the local farmers’ resistance to incorporating their homesteads into jointly managed farms.In the meantime, a parallel, regionwide armed revolt referred to as the Wooded area Brothers had additionally sprung up. Operation Priboi aimed to do away with enhance for the ones rural guerrillas by way of uprooting the populace the place they operated, together with their households and doable recruits.Tale continues beneath commercialAn estimated 150,000 other folks had been deported in Operation Priboi, or 2 p.c of the inhabitants of the 3 Baltic republics. However in contrast to in 1941, 70 p.c of the ones deportees had been ladies and kids, who had been despatched to farms to paintings, and a way smaller proportion of the deported died. The majority of the deportees had been sooner or later in a position to go back house within the past due Nineteen Fifties underneath the de-Stalinization program initiated by way of Nikita Khrushchev.Efforts to commemorate the sufferers of the 2 deportations had been noticed by way of Moscow as a danger, and with excellent reason why: They changed into sure up with the Baltic peoples’ want to reclaim their independence.“It's no twist of fate that the primary anti-Soviet public demonstrations within the Baltic States came about in Riga with a wreath-laying on the Freedom Monument on June 14, 1987, the anniversary of the 1941 genocide,” mentioned Pauls Raudseps, an American-born journalist who has been operating in Riga because the Nineteen Nineties.Tale continues beneath commercial“In 1987, this demonstration used to be extraordinarily dangerous — glasnost used to be nonetheless now not very complicated and public discussions of the deportations and the Soviet profession truly handiest began a 12 months later,” mentioned Raudseps, whose great-uncle and his spouse and 1-year-old daughter had been a few of the first wave of deportees. (They survived.)However the stunned Soviet government allowed the demonstration to continue. 4 years later, the usS.R. dissolved. The yearly observances of the 2 deportations at the moment are nationwide days of commemoration within the 3 Baltic international locations.“The concern, anger, destruction of lives, households, houses and careers have at all times stayed in our cultural reminiscence,” mentioned Jagodin, the director of the Museum of Occupations and Freedom, which opened in 2003 to maintain the reminiscence of the 2 Soviet occupations of 1940-41 and 1944-1990, in addition to the intervening German one.Tale continues beneath commercialNow, with the scoop of the reported abductions 1,200 miles away in Mauripol, the ones preserved reminiscences were stirred up as soon as once more for lots of Estonians, in addition to their Latvian and Lithuanian neighbors, Jagodin mentioned.“I don’t know if lately in Ukraine they're settling on deported other folks by way of ethnicity, language, schooling or social standing,” mentioned Jagodin, “however in each 1941 and 1949, one of the most Soviets’ major targets used to be to execute the elite and those who would stay Estonian tradition, language and id alive.”Each deportations had been “focused assaults in opposition to the Estonian country,” she mentioned, which seems like what the Russians are reportedly doing in Ukraine.Tale continues beneath commercialThus the added fervor and

emotion that accompanied remaining week’s commemorations of the March deportations in Riga, Tallinn and Vilnius, in addition to across the Baltics. Within the shadow of Ukraine, the ones deportations now not appear see you later in the past or up to now away.“Commemorations like the only remaining week advertise the concept nationwide independence is an existential subject,” mentioned Gints Apals, director of public historical past on the Latvian Museum of Career in Riga, “in addition to a ensure in opposition to the repetition of an identical occasions one day.”Gordon F. Sander is a journalist and historian based totally in Riga. He's Nordic/Baltic correspondent for the Christian Science Track. He's additionally a visiting lecturer in historical past on the Latvian Academy of Tradition. [ad_2] #Russia #deported #Ukrainians #Soviets #kidnapped #Baltic #electorate

0 notes

Photo

Sigismunds Vidbergs (1890-1970), ''Folk and Fairy Tales'', 1985 Source

#sigismunds vidbergs#latvian artists#folk and fairy tales#folk tales#fairy tales#dragons#henry cuyler bunner#children's books

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 3.12

Holidays

Alfred Hitchcock Day

Arbor Day (China, Taiwan)

Aztec New Year

Coca Cola Bottle Day

Day of the Seven Billion

Detransition Awareness Day

Employee Day

Fireside Chat Day

Flag Day (Saudi Arabia; Sweden)

Girl Scout's Day

Grækarismessa (Traditionally, the Oystercatcher, the Faroe Islands' national bird returns this day)

Gregoru Diena (Ancient Latvian groundhog day)

International Day of Tweeters

International Yes Day

IUGR (Intrauterine Growth Restriction) Awareness Day

Mammal Big Day

Martyrdom of Hypatia of Alexandria

Mourning for Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare Day (Papua New Guinea)

National Alfred Hitchcock Day

National Arts Advocacy Day

National Christian Day

National Map Day

National Ruth Day

National Shield Day (Argentina)

National Working Moms Day

Plant a Flower Day

312 Day

Tree Day (Republic of Macedonia)

World Agnihotra Day

World Day Against Cyber Censorship (UN)

World Glaucoma Day

Youth Day (Zambia)

Z Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Eskimo Pie Day

National Baked Scallops Day

National Milky Way Day

2nd Sunday in March

Charter Day (Observed; Pennsylvania) [2nd Sunday]

Daylight Savings Day [2nd Sunday; DST Day] (a.k.a. ...

Check Your Batteries Day

Check Your Smoke Alarms and Carbon Monoxide Detectors Day

Fill Our Staplers Day

Napping Season begins

Summer Time

Festival of Incompetence Day [2nd Sunday]

Holmenkellen Day (Winter Festival; Norway) [2nd Sunday]

International Day of Planetariums [2nd Sunday]

National Dry Shampoo Day [2nd Sunday]

National I Am Day [2nd Sunday]

Selection Sunday [Sunday before March Madness; NCAA]

Sunshine Week begins [Sunday before 16th]

World Folk Tales and Fables Week begins [2nd Sunday]

World Glaucoma Week begins [2nd Sunday]

Independence Days

Mauritius (from UK, 1968)

Woodlandia (Declared; 2019) [unrecognized]

Feast Days

Alphege (Christian; Saint)

Aristippus (Positivist; Saint)

Bernard of Carinola (or of Capua; Christian; Saint)

Blot to Odhinn All-Father (Pagan)

Cuddle an Accountant Day (Pastafarian)

Cuddle a Policeman Day (Pastafarian)

End of the World by Sekhmet (Egyptian Warrior Goddess)

Feast of Marduk (Mesopotamian)

Fiesta de las Fallas begins (Spain)

Fina (Christian; Saint)

The Genie (Muppetism)

Gorgonius, Peter Cubicularius and Dorotheus of Nicomedia (Christian; Saints)

Gregor the Great (Christian; Saint)

Houdini Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

John Singer Sargent Day (Artology; Saint)

Maha Shivaratri (Festival of Shiva; Hindu)

Maximilian of Tebessa (a.k.a. of Numidia; Christian; Saint)

Mura (a.k.a. McFeredach; Christian; Saint)

Paul Aurelian (a.k.a. Paul of Cornwall; Christian; Saint)

Pope Gregory I (Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Catholic Church, and Anglican Communion)

Seraphina (Christian; Saint)

Theophanes the Confessor (Christian; Saint)

Third Sunday in Lent (Western Christianity) (a.k.a. ...

Oculi Sunday

Scrutiny Sunday

Septuagesima Sunday

Veneration of the Cross

Wenchang Wang Day (God of Literature; China)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Butsumetsu (仏滅 Japan) [Unlucky all day.]

Prime Number Day: 71 [20 of 72]

Unfortunate Day (Pagan) [19 of 57]

Premieres

Bad Hair Day, by Weird Al Yankovic (Album; 1996)

Bend It Like Beckham (Film; 2003)

The Cat in the Hat, by Dr. Seuss (Children’s Book; 1955)

East of Eden, by John Steinbeck (Novel; 1953)

Fanfare for the Common Man, by Aaron Copland (Fanfare; 1943)

Glass Houses, by Billy Joel (Album; 1980)

Hachi: A Dog’s Tale (Film; 2010)

It’s Like That, by Run-DMC (Song; 1983)

La Sylphide, by Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer and Adolphe Nourrit (Ballet; 1832)

Live at the Sunset Strip, by Richard Pryor (Stand-Up Comedy Show; 1982)

Longitude, by Dava Sobel (Book; 1996)

Nothing Like It In the World, by Stephen E. Ambrose (Book; 2001)

Resident Evil (Film; 2002)

She’s Out of My League (Film; 2010)

The Shield (TV Series; 2002)

The Velvet Underground and Nico, by The Velvet Underground (Album; 1967)

Where Eagles Dare (Film; 1969)

Wonderfalls (TV Series; 2004)

Today’s Name Days

Almut, Beatrix, Serafina (Austria)

Bernard, Budislav, Fina (Croatia)

Řehoř (Czech Republic)

Gregorius (Denmark)

Rego, Reio (Estonia)

Reijo, Reko (Finland)

Justine, Pol (France)

Almut, Beatrix, Serafina (Germany)

Theofania, Theofanis (Greece)

Gergely (Hungary)

Massimiliano, Simplicio, Zeno, Zenona (Italy)

Aija, Aiva, Aivis, Ausmins, Gregors (Latvia)

Darmantė, Galvirdas, Grigalius (Lithuania)

Gregor, Gro (Norway)

Bernard, Blizbor, Grzegorz, Józefina, Wasyl (Poland)

Simeon, Teofan (Romania)

Kira, Marina (Russia)

Gregor (Slovakia)

Inocencio (Spain)

Victoria, Viktoria (Sweden)

Maryna (Ukrainę)

Graig, Grayson, Greg, Gregoria, Gregorio, Gregory, Orion (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 71 of 2023; 294 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 7 of week 10 of 2023

Celtic Tree Calendar: Nuin (Ash) [Day 22 of 28]

Chinese: Month 2 (Yi-Mao), Day 21 (Ji-Si)

Chinese Year of the: Rabbit 4721 (until February 10, 2024)

Hebrew: 19 Adar 5783

Islamic: 19 Sha’ban 1444

J Cal: 10 Ver; Threesday [10 of 30]

Julian: 27 February 2023

Moon: 74%: Waning Gibbous

Positivist: 15 Aristotle (3rd Month) [Aristippus]

Runic Half Month: Beore (Birch Tree) [Day 2 of 15]

Season: Winter (Day 82 of 90)

Zodiac: Pisces (Day 21 of 29)

0 notes

Text

Holidays 3.12

Holidays

Alfred Hitchcock Day

Arbor Day (China, Taiwan)

Aztec New Year

Coca Cola Bottle Day

Day of the Seven Billion

Detransition Awareness Day

Employee Day

Fireside Chat Day

Flag Day (Saudi Arabia; Sweden)

Girl Scout's Day

Grækarismessa (Traditionally, the Oystercatcher, the Faroe Islands' national bird returns this day)

Gregoru Diena (Ancient Latvian groundhog day)

International Day of Tweeters

International Yes Day

IUGR (Intrauterine Growth Restriction) Awareness Day

Mammal Big Day

Martyrdom of Hypatia of Alexandria

Mourning for Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare Day (Papua New Guinea)

National Alfred Hitchcock Day

National Arts Advocacy Day

National Christian Day

National Map Day

National Ruth Day

National Shield Day (Argentina)

National Working Moms Day

Plant a Flower Day

312 Day

Tree Day (Republic of Macedonia)

World Agnihotra Day

World Day Against Cyber Censorship (UN)

World Glaucoma Day

Youth Day (Zambia)

Z Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Eskimo Pie Day

National Baked Scallops Day

National Milky Way Day

2nd Sunday in March

Charter Day (Observed; Pennsylvania) [2nd Sunday]

Daylight Savings Day [2nd Sunday; DST Day] (a.k.a. ...

Check Your Batteries Day

Check Your Smoke Alarms and Carbon Monoxide Detectors Day

Fill Our Staplers Day

Napping Season begins

Summer Time

Festival of Incompetence Day [2nd Sunday]

Holmenkellen Day (Winter Festival; Norway) [2nd Sunday]

International Day of Planetariums [2nd Sunday]

National Dry Shampoo Day [2nd Sunday]

National I Am Day [2nd Sunday]

Selection Sunday [Sunday before March Madness; NCAA]

Sunshine Week begins [Sunday before 16th]

World Folk Tales and Fables Week begins [2nd Sunday]

World Glaucoma Week begins [2nd Sunday]

Independence Days

Mauritius (from UK, 1968)

Woodlandia (Declared; 2019) [unrecognized]

Feast Days

Alphege (Christian; Saint)

Aristippus (Positivist; Saint)

Bernard of Carinola (or of Capua; Christian; Saint)

Blot to Odhinn All-Father (Pagan)

Cuddle an Accountant Day (Pastafarian)

Cuddle a Policeman Day (Pastafarian)

End of the World by Sekhmet (Egyptian Warrior Goddess)

Feast of Marduk (Mesopotamian)

Fiesta de las Fallas begins (Spain)

Fina (Christian; Saint)

The Genie (Muppetism)

Gorgonius, Peter Cubicularius and Dorotheus of Nicomedia (Christian; Saints)

Gregor the Great (Christian; Saint)

Houdini Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

John Singer Sargent Day (Artology; Saint)

Maha Shivaratri (Festival of Shiva; Hindu)

Maximilian of Tebessa (a.k.a. of Numidia; Christian; Saint)

Mura (a.k.a. McFeredach; Christian; Saint)

Paul Aurelian (a.k.a. Paul of Cornwall; Christian; Saint)

Pope Gregory I (Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Catholic Church, and Anglican Communion)

Seraphina (Christian; Saint)

Theophanes the Confessor (Christian; Saint)

Third Sunday in Lent (Western Christianity) (a.k.a. ...

Oculi Sunday

Scrutiny Sunday

Septuagesima Sunday

Veneration of the Cross

Wenchang Wang Day (God of Literature; China)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Butsumetsu (仏滅 Japan) [Unlucky all day.]

Prime Number Day: 71 [20 of 72]

Unfortunate Day (Pagan) [19 of 57]

Premieres

Bad Hair Day, by Weird Al Yankovic (Album; 1996)

Bend It Like Beckham (Film; 2003)

The Cat in the Hat, by Dr. Seuss (Children’s Book; 1955)

East of Eden, by John Steinbeck (Novel; 1953)

Fanfare for the Common Man, by Aaron Copland (Fanfare; 1943)

Glass Houses, by Billy Joel (Album; 1980)

Hachi: A Dog’s Tale (Film; 2010)

It’s Like That, by Run-DMC (Song; 1983)

La Sylphide, by Jean-Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer and Adolphe Nourrit (Ballet; 1832)

Live at the Sunset Strip, by Richard Pryor (Stand-Up Comedy Show; 1982)

Longitude, by Dava Sobel (Book; 1996)

Nothing Like It In the World, by Stephen E. Ambrose (Book; 2001)

Resident Evil (Film; 2002)