#LAVRENTIY BERIA

Text

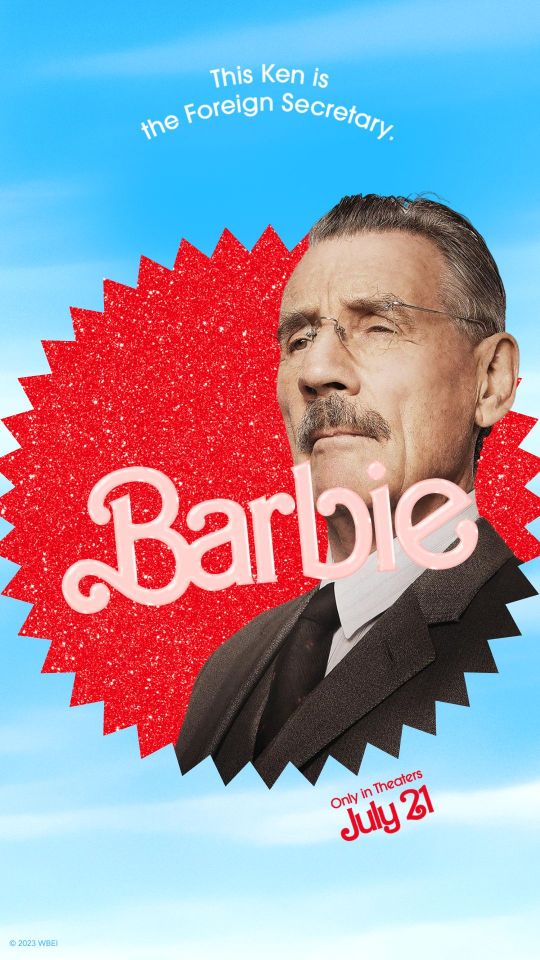

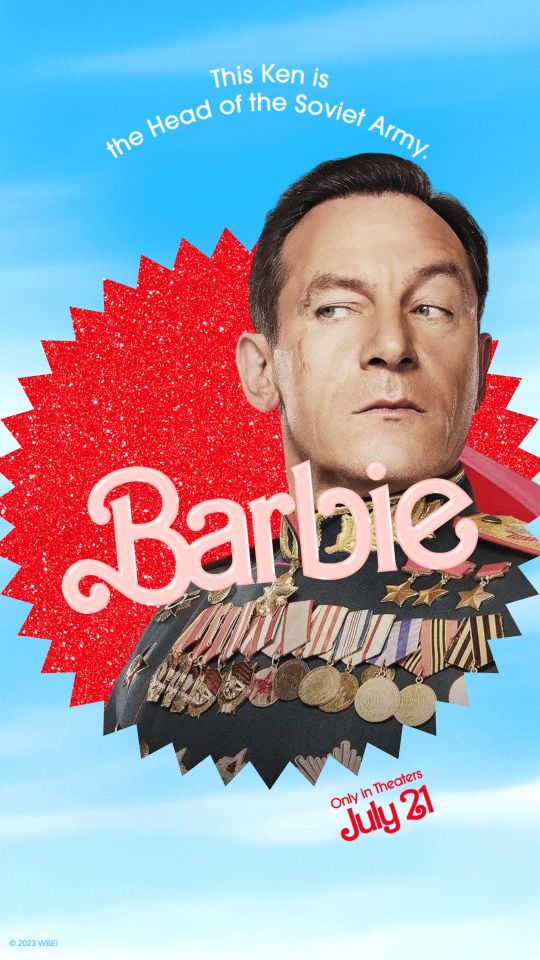

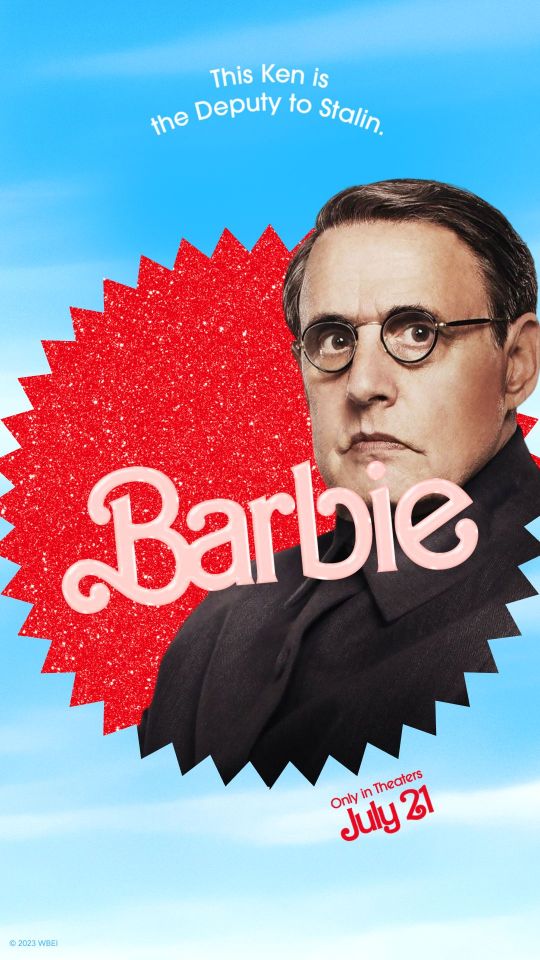

The Death of Stalin, but the poster is... Barbie?!

#the death of stalin#death of stalin#michael palin#steve buscemi#jason isaacs#simon russell beale#jeffrey tambor#rupert friend#andrea riseborough#paul whitehouse#armando iannucci#vyacheslav molotov#nikita khrushchev#georgy zhukov#lavrentiy beria#georgy malenkov#vasily stalin#svetlana alliluyeva#anastas mikoyan#forgot i made this#for some reason i cant find photos of the og poster with bulganin and kaganovich#why??? are they late??? sorry#anyways!!#late barbie post#viv's post#viv's edit

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

Look no further than the headlines around the world.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

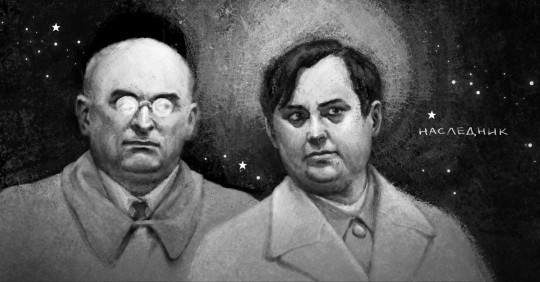

Malenkov and Beria analysis (more like a ramble) through Bataille

Georges Bataille, in Erotism: Death and Sensuality, examines eroticism as an act of transgression, where power, violence, and intimacy converge in a space that defies conventional boundaries. For Bataille, eroticism is not confined to the sexual act but extends to any interaction where the limits of self and other dissolve, often manifesting through domination and submission. This concept can be applied to the relationship between Malenkov and Beria, two prominent figures in Stalin's inner circle, whose political alliance was marked by layers of trust and betrayal. As head of the NKVD, Beria wielded immense power, manipulating both state terror and personal relationships. Malenkov, strategically allied with Beria, found himself entangled in a political dance that embodied the very essence of Bataille’s eroticism—where power and submission are intertwined in a dangerous, intimate dance that blurs the boundaries between the sacred and the profane.

The homoerotic undertones of their relationship emerge when one considers the deep psychological intimacy that existed alongside their power dynamics. For Bataille, the sacred and the profane are intertwined in acts of transgression that break down traditional societal boundaries. Beria and Malenkov’s relationship, though political on the surface, was imbued with a kind of ritualistic intimacy that crossed into the realm of the sacred. Their interactions—rooted in fear, loyalty, manipulation, and the ever-present threat of betrayal—transgressed the profane limits of conventional political relationships, creating a closeness that Bataille might interpret as inherently erotic. Beria’s ruthless use of power, his penetrating influence into the lives of others, and his ability to manipulate political favor suggest a deeper, more intimate connection with Malenkov, one that reflects the eroticization of power and violence Bataille discusses.

Bataille’s notion of the dissolution of boundaries between the sacred and the profane provides a lens through which we can understand the shifting dynamics of Malenkov and Beria’s relationship. Their interactions took place within the sacred confines of Stalin’s inner circle, where loyalty was paramount and betrayal was taboo. Yet, their secretive dealings and eventual betrayals constantly blurred the line between comradeship and treachery. This breaking of boundaries echoes Bataille’s idea of eroticism as a process that involves transgressing societal norms and encountering the erotic in acts that are politically or socially violent. Malenkov and Beria’s relationship can thus be seen as a continuous process of transgression, where the boundaries between dominance, submission, and comradeship are repeatedly crossed and redefined, resulting in an erotic dynamic that is deeply intertwined with power and violence.

The closeness between Malenkov and Beria, captured in the quote, “none of us had a tenth of that closeness, that intimacy that Malenkov had [with Beria],” highlights the significance of their relationship not only on a personal level but also within the highly volatile world of Stalinist politics. This bond was not just a matter of personal affection; it became instrumental in their political survival and mutual advancement. Their relationship, long-established and marked by Beria’s visits to Malenkov in Moscow even before 1937, suggests that their connection was built on more than political expediency. It was a partnership deeply rooted in personal trust, which provided them both with a degree of protection amid Stalin’s purges and the ever-present threat of political rivalries. The familiarity of their interactions, evident in Beria's informal and affectionate language when writing to Malenkov after his arrest, where he referred to him as "dear Georgy" and used the informal "you," further emphasizes the profound level of trust and intimacy between them. Such personal closeness was almost unheard of in Stalin’s inner circle, where relationships were largely governed by fear, suspicion, and the constant threat of betrayal. Their bond not only set them apart but also served as a source of political strength, allowing them to work together more effectively.

Malenkov and Beria’s relationship was marked by a daily ritual of meetings and consultations, often conducted in private, away from the prying eyes of other Soviet officials. These meetings were not mere bureaucratic obligations but were characterized by an intimacy that suggested a deeper connection. According to historical accounts, Malenkov and Beria shared a unique closeness that was rare in the volatile and paranoid environment of Stalin's inner circle. Their bond was not solely based on political expediency but seemed to transcend into the personal sphere, creating an exclusive partnership that few could penetrate.

Bataille distinguishes the sacred from the profane by positioning the sacred as that which is set apart from the mundane, often imbued with both fascination and fear. The sacred, according to Bataille, involves experiences that are intensely charged with emotional and existential weight—moments that break away from the ordinary (the profane) and touch on something profound, whether divine or deeply transgressive. In the case of Malenkov and Beria, their daily meetings, though appearing routine, take on a sacred quality because they are not just procedural but are imbued with an exclusivity and secrecy that elevates them beyond the ordinary political exchanges. This secrecy and ritualization signify a departure from the profane world of Soviet politics, where interactions are typically governed by strict formality and surveillance.

Central to Bataille’s theory of eroticism is the concept of transgression. For Bataille, eroticism is not simply about sexual acts but about crossing boundaries that are usually maintained to preserve order within society. These boundaries can be physical, moral, or social, and their transgression leads to experiences that are sacred because they disrupt the ordinary flow of life, entering into the realm of the extraordinary. In Malenkov and Beria’s relationship, the act of meeting in seclusion, away from the eyes of other Soviet officials, represents a form of transgression. It is not just the secrecy but the very act of creating a private, exclusive space that becomes transgressive. In a system where every action is scrutinized, where loyalty is constantly tested, and where power dynamics are always in flux, the ability to carve out a space for private, intimate interaction is in itself an act of defiance against the established order.

Bataille's work emphasizes the importance of transgression in human relationships. He argues that true human connection often involves breaking societal norms and engaging in behaviors that are considered taboo or transgressive. In the context of Beria and Malenkov, their relationship exemplifies this principle. Bataille’s framework posits that true human connection involves not just emotional intimacy but also a willingness to transgress societal norms.

Georges Bataille's concepts of the "sacred" and "profane" offer a nuanced perspective on the dynamics of power and transgression in the context of Beria and Malenkov's relationship. According to Bataille, the sacred represents a realm of absolute power and sovereignty, while the profane is the domain of everyday life and mundane activities.

Beria's actions can be seen as embodying the sacred. His control over the security apparatus and his ability to dispense life and death made him a figure of absolute power. His sexual predations, however, were a profane act, one that undermined the dignity of his office and revealed a deep-seated corruption of power. This dichotomy between the sacred and profane in Beria's actions highlights how his absolute power was simultaneously a source of strength and a potential weakness. His ability to exert control over others was matched by his inability to control his own desires, leading to a downfall that was both personal and political.

Malenkov's relationship with Beria can also be analyzed through Bataille’s lens. Malenkov's willingness to compromise his own authority and the party's influence by implementing policies favorable to Beria can be seen as a profane act. By doing so, he was undermining the sacred institution of the Communist Party and the ideals it represented. However, this compromise also reflects a deeper understanding of the power dynamics at play. Malenkov's inability to challenge Beria directly suggests that he was aware of the sacred nature of Beria's power and chose to navigate the complex web of alliances and rivalries within the Soviet leadership rather than confront it head-on.

The profane nature of Malenkov’s compromise is underscored by his tacit acknowledgment of Beria’s unparalleled authority. Beria’s control over the secret police and his role in the purges granted him a sacred-like status within the power structure, where fear and reverence coalesced around him. Malenkov’s reluctance to challenge Beria directly reflects a recognition of the sacred nature of Beria’s power—a power that, while profane in its methods, was deeply embedded in the political realities of Stalinist governance. In this context, Beria’s authority functioned almost as a form of taboo; challenging him could mean political ruin or even death. This sacred-profane duality in Beria’s position created an environment where Malenkov, despite his nominal authority within the Party, was compelled to navigate carefully, avoiding direct confrontation and instead seeking accommodation.

Malenkov’s inability to confront Beria head-on also illustrates the broader tension between ideology and realpolitik that characterized the Soviet leadership. While the Party ostensibly adhered to Marxist-Leninist principles, the realities of power often required pragmatism and strategic compromises. Malenkov’s alliance with Beria, though detrimental to the integrity of the Party’s sacred ideals, was an attempt to secure his own political survival in a landscape defined by shifting loyalties and brutal purges. His actions, therefore, highlight the fragility of ideological purity within the Soviet system, where the sacred ideals of communism frequently clashed with the profane necessities of political maneuvering.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, Malenkov’s dependence on Beria can be understood as a manifestation of his deep-seated insecurities and need for external validation. This dependency is emblematic of transference, a psychological phenomenon wherein an individual projects their unresolved emotional needs onto a significant authority figure. In this case, Malenkov’s emotional vulnerability and quest for stability in a politically volatile environment led him to rely heavily on Beria. Beria’s authoritative presence and control over crucial institutions, such as the secret police, heightened Malenkov’s need for guidance and protection, making him particularly susceptible to transference.

Bataille’s theoretical framework, which differentiates between the sacred and the profane, further elucidates this complex relationship. The sacred aspect of their interaction is reflected in the almost reverential aura that Beria commanded. His position of power and influence created an image of invulnerability and mystique, leading Malenkov to seek Beria’s approval and align himself with his formidable authority. This sense of reverence, coupled with Malenkov’s own need for security, transformed Beria into a near-sacred figure whose endorsement was crucial for Malenkov’s psychological and political stability.

Malenkov's characterization as a figure of sensitivity and political timidity, often compared to a frightened goat under Beria’s control, reflects a broader psychological and political dependency that can be deeply analyzed through Georges Bataille’s concepts of the sacred and profane. This metaphor of Malenkov as a frightened goat encapsulates his vulnerability, his emotional and political instability, and his constant need for guidance and protection. Beria, on the other hand, functions as the authoritarian figure who “holds tight” to Malenkov, maintaining control over him in both a psychological and political sense. The dynamic between these two figures, when viewed through Bataille’s theoretical framework, reveals the intricate and often contradictory relationship between personal power, institutional authority, and the psychological dependencies that underlie them.

Malenkov’s sensitivity is emblematic of a deeper psychological need for security and affirmation. In the volatile political environment of the Soviet Union, where leaders were constantly under threat from purges, political machinations, and shifting allegiances, Malenkov was particularly vulnerable. His characterization as a “frightened goat” speaks to his inability to assert himself independently, both politically and emotionally. His reliance on Beria is thus not merely a matter of political expediency; it is also a reflection of his profound insecurity. Malenkov needed the assurance that Beria, with his seemingly untouchable power, could provide. In this sense, Malenkov’s sensitivity is not just a personal trait but a political liability that necessitated his subservience to stronger figures like Beria.

Beria, by contrast, is often portrayed as the one who holds Malenkov tightly in his grip. In doing so, Beria exercises control over Malenkov's actions, ensuring that he does not “run amok” or stray from the path Beria has laid out for him. This dynamic can be seen as an expression of Bataille’s concept of the sacred. Beria, with his control over the secret police and his role in the purges, occupies a position of immense power and influence within the Soviet hierarchy. His authority is so overwhelming that it transcends the ordinary mechanisms of political power, taking on a sacred quality. For Malenkov, Beria’s power is not simply a tool of political control; it is something to be revered, something beyond the reach of mere political calculation. This sacred aura surrounding Beria is what compels Malenkov to submit to his authority, seeking protection and stability in the face of his own political and emotional fragility.

The metaphor of Malenkov as a frightened goat, then, can be understood through the lens of Bataille’s sacred-profane dichotomy. Malenkov’s sensitivity and political timidity place him in the realm of the profane—the mundane, the vulnerable, the ordinary. He is a figure whose actions are driven by fear and insecurity, and who lacks the strength to assert himself independently. Beria, by contrast, represents the sacred—an authority figure whose power transcends the ordinary and takes on a near-mystical quality. For Malenkov, Beria’s sacred power is both a source of fear and reverence. He knows that to defy Beria would be to invite political disaster, yet to align with him is to diminish his own authority and the sacred ideals of the Communist Party.

The transference between Malenkov and Beria can be seen as a byproduct of the power imbalance that defined their relationship. Malenkov's psychological vulnerabilities—his insecurities and need for approval—were magnified by the dangers of the political environment. This led him to project his need for stability onto Beria, who, with his commanding control over the mechanisms of state terror, embodied the security and guidance Malenkov desperately sought. Malenkov’s emotional vulnerability, particularly his need for validation, further deepened his dependence on Beria, as he looked to Beria not just for political survival but for psychological affirmation. In this way, Malenkov's relationship with Beria was a complex interplay of psychological dependency and political strategy, underpinned by a profound need for security and guidance.

#i love maleria#maleria#lavrentiy beria#georgy malenkov#ussr#soviet union#georges bataille#please I'm so Bataille rotted

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1 of posting my commie faves. Exhibit one: Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite detail in Red Monarch is the scene at the end where Khrushchev stands back and watches Beria as he strangled Stalin because it is so similar to a scene in Death of Stalin that it couldn’t be a coincidence.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

just Beria and Malenkov fanart

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

this isn't the *worst* thing i've ever seen on eBay but I'm trying to get in the head of someone who's like "I need a bust of disgraced former NKVD head Lavrentiy Beria"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something a friend of mine posted on a discord server.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show me the man and I'll find you the crime.

Attributed to Lavrentiy Beria, Stalin's secret police chief

0 notes

Text

Meet the Politburo...

Red Monarch (1983, dir. Jack Gold) || The Death of Stalin (2017, dir. Armando Iannucci)

#red monarch#the death of stalin#movies#ussr#nikita khrushchev#vyacheslav molotov#anastas mikoyan#lazar kaganovich#lavrentiy beria#georgy malenkov#michael palin#steve buscemi#jeffrey tambor#simon russell beale#paul whitehouse#dermot crowley#david suchet#nigel stock#peter woodthorpe#brian glover#george a cooper#such a shame theres no bulganin or zhukov for red monarch!#and voroshilov in the death of stalin!#armando iannucci#jack gold

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

ladles and gentlebeasts, our former minister of justice/prosecutor general!

[image description: screenshot of a dec 5, 2023 tweet by zbigniew ziobro. there's a photo of a hand holding a rainbow flag linking to radiomaryja.pl, captioned "remember: LGBTTQQIAAP. soon you'll be opening yourselves to prosecution if you omit any of these letters."

readers added context: "not only there's nothing about making the full "LGBTTQQIAAP" acronym mandatory at the provided link, it even quotes Barbara Nowak as talking about "the LGBT community"."]

#polblr#fucking lavrentii beria kinnies#can't wait to see the infighting in pis after ye olde duck is gone one way or another#this fucker has so much kompromat on so many people#oh and there's tribunal of state! if the new set has the spine to go through with it

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#This is me being cringe#I seldom write poems about other people but here we go#maleria#i love maleria#lavrentiy beria#georgy malenkov#ussr#soviet#poetry#web weaving

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding your post on Stalin and Lenin, I want to ask in good faith: how can honest Communists, in good conscience, acknowledge the material harm and the death tolls of the deportations of the Crimean Tatars, Soviet Koreans, and Chechens + Ingush carried out by Stalin's administration?

I at least understand why Marxist-Leninists dispute calling the Holodomor and Kazakh famines genocides, on the grounds that they came about as a mix of failed policy, bad weather, and unintended consequences.

However, while Stalin's influence on the Famines is debatable, allowing the deportations to be carried out (which DO constitute a genocide) must certainly fall on his head. This is doubly so because Lavrentiy Beria - the principal architect of the Crimean Tatar and Chechen deportations - was a close ally of Stalin.

A big reason I ask this is because I frequently see other communists either gloss over the material harm of these deportations, or treat them as a regrettable footnote in an otherwise proud career. I find both approaches problematic, because I do not see them as an honest assessment of Stalin's wrongdoing with regards to ethnic minorities within the Soviet Union.

I thank you for your time, and I look forward to reading your assessment, should you chose to answer it. Have a good day.

[context]

I'll get to the ask itself in a moment, but first I want to point out how you're doing exactly what the post you're replying to is criticizing, how every mistake and imperfect policy of the USSR between 1924 and 1953 is scapegoated to Stalin. You're ignoring both the very important structures of democracy and accountability within the party as well as in the administration of the state. He wasn't a dictator and policy was not a direct extension of the man's thoughts. The party leadership was a collective organ made up of at least a dozen people, of which Stalin was simply the chairman, with the same vote as everyone else. And every single one of these members were beholden to democratic recall at any time.

Let's start on the common ground, we understand that the famine which struck Ukraine, southern Russia and western Kazakhstan in the early 1930s has a context of cyclical famines, grain hoarding, rushed collectivization, and bad weather. There has been a strong effort on the part of capitalist powers to both exaggerate the effects of the famine and to place it all with intent to exterminate Ukranians specifically. The policy of collectivization and antagonism towards the grain-hoarding rich peasants was one approved by and carried out by hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions. We can debate the degree of maliciousness, the severity of its effects, etc. But what is indisputable once you know just a little of how the USSR worked, to pretend that it could all be carried out by Stalin's sole will is absurd.

And what is the context of the deportations? The fascist invasion of the USSR. This is an extraordinary circumstance, every facet of the USSR was being attacked and threatened with sabotage. It wasn't even the first time they had had to deal with internal sabotage, like it was revealed in the trials following the assassination of Kirov. Throughout the 30s, Nazi Germany's strongarm diplomacy was practically enabled by their ability to create fifth columns, to instigate conflict and to infiltrate. They were in the process of setting up a coup d'etat in Lithuania when, with only a week to spare, it was voted that Lithuania would join the USSR. So, the fear that, as the front advanced, the nazis would do everything in their power to turn the tapestry of nationalities close to the front against the USSR, wasn't only unfounded, it was certain. Fascists are also quite famously brutal against the minorities in the territories they conquered. Their modus operandi whenever they captured a population was to kill any elected leaders and start to instigate anti-semitism.

This was the rationale that drove the policy of resettlement. It was a rushed wartime decision, such was the context, and people definitely died unnecessarily in transport. They decided that the negative consequences of resettlement outweighed the risk of sabotage, destroyed supply lines, and of a completely certain brutal destiny for these minorities if the front advanced past them. It was not a genocide, and it had nothing to do with whatever personal relationship you think Stalin had with Beria. (As a tangent, in this interview, Stalin's bodyguard said that Beria was "neither his [Stalin's] right hand man or left hand man"). I reiterate though, the personal relationships of one man did not dictate the policy decided on democratically by the CPSU.

I don't see the problem in understanding the context of these decisions and understanding the rationale behind them without kneejerking into discounting Stalin's competency. It's very easy to criticize a decision with 80 years of hindsight, without the pressure of the largest land invasion ever carried out advancing steadily. You can't understand the policies of a country containing hundreds of millions of people and hundreds of nationalities through the lens of a single man's personal failings, especially in wartime. Admitting these mistakes, but understanding the context in which they were made, is the only way to learn from other attempts at developing socialism. What is not productive is to insist on pinning every mistake, every unnecessary pain, every inefficiency, as the wrongdoings of a single man. It's dishonest to both the past, and to how communists organize today.

#ask#anon#seriousposting#re-reading this and I want to make my tone clear#I'm not trying to be aggressive towards you anon#I'm just trying to use clear language and be direct about this topic#I really appreciate the question and you clear efforts to be level-headed about this

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

I heard Lenin loved Samyang 2x Spicy Ramen so much he proposed the 3x Spicy, but unfortunately passed before he could try it.

They executed Lavrentiy Beria by forcing him to eat three packages of Samyang 3x Spicy sauce, he did not make it on his first try

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of you need—NEED—to understand that "the other side" is not one homogeneous mass of all the same ideas. They're just as varied and ideologically diverse and full of in-fighting and arguments as your side is.

More to the point, if you see someone apparently taking a position that runs contrary to some other thing the other side believes, it's probably because that particular person didn't believe in that particular position. The people hyping up Neuralink human trials are different than the people who screamed for years about satanists putting chips in our brains; Muskovites are different from End-Times Fundamentalist Christians, even if they sometimes say similar things about "Woke Ideology" or the federal deficit.

The larger point is that you shouldn't study politics as a two-sides thing, but as a big pile of questions that you can have any combination positions on. Sometimes you can see correlations, sometimes you can draw lines are groupings. "Left-Wing" can cover Bernie Sanders, Lavrentiy Beria, and Peter Kropotkin; It would be weird if they didn't have a ton of disagreements.

Most of the time, if you accuse someone of being hypocritical it's either because you're confusing one part of a group for another.

174 notes

·

View notes