#Lá na Leanbh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

In the Liturgical calendar, today is the Feast of the Holy Innocents or Lá Crosta na Bliana or the cross day of the year in Irish. The day was also known as ‘Lá na Leanbh’ (Day of the Children). In Irish tradition this day was seen as an unlucky day because it commemorated the murder of children by King Herod. In consequence, probably of the feeling of horror attached to such an act of atrocity,…

View On WordPress

#Cross Day of the Year#Feast Day#Feast of the Holy Innocents#King Herod#Lá Crosta na Bliana#Lá na Leanbh

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIMING: Worm Day in Feb LOCATION: An appropriate battlefield PARTIES: @kadavernagh & @banisheed SUMMARY: Worms fight for the pride of their banshee. Love is a battlefield. CONTENT: Wormspice

“Lá na bPéist,” Siobhan said, grinning the way an animal sometimes only seems to right before it lunges. “Last worm writhing, yes.”

War would be waged at dawn. Regan marched into the clearing she had designated for Siobhan, a big tin jar in her hands, previously filled with coffee grounds, and now full of writhing worms. She didn’t think her newly-purchased worms truly desired anything – what an enviable, simple life in many ways – and they especially had no interest in fighting Siobhan’s worms. But this was a matter of pride. Siobhan assumed that Regan’s worms were undignified and meek, odorless and scrawny, and Regan was tired of bearing her insults.

Her skin prickled as a long figure appeared across the clearing, the sun creeping up behind her and casting her face in shadow. She would have her own worms with her. And if they were as girthy as Siobhan claimed, why could Regan not see them from here? Not so impressive.

“Lá na bPéist,” Regan greeted her. It was the customary way. Day of the Worms. There was no ‘happy’ in front of it; it was only a simple and respectful declaration of the day. “My worms challenged you, and I picked the location, so I will be generous and allow you to set reasonable perimeters. Will this be down to the last worm standing – so to speak – or do you have something else in mind?”

--------

Violence was a necessity. Since the first forms of microscopic life, it seemed, violence was a language to claim dominance. Or so Siobhan assumed, banshee literature was often flirtatious with the truth. At least one book claimed that all life was born out of a big bone, contradicted by another book that claimed the big worm in the sky birthed them which was also contradicted by another book that was simply a picture of a skeleton shrugging. Science is an afterthought but violence, still, was an art. What Regan didn’t know, with her skinny worms, was that their little worm war didn’t start here. Their war began the moment Siobhan laid eyes on her unseasonable winter coat. In order for something to be strong, something else has to be weak: a rule of language that Siobhan knew intimately. She wouldn’t be weak.

Her happy, healthy, girthy worms writhed in the box she brought them in. She was pained to rip them from their happy home inside her compost system, where they had lived for months, lovingly tended to, fertilizing the earth that she used for her garden. For Death to be appreciated, Life needed to be respected as well. But there was no doubt in Siobhan’s mind that this truth escaped Regan. She probably purchased her worms wholesale online.

“Lá na bPéist,” Siobhan said, grinning the way an animal sometimes only seems to right before it lunges. “Last worm writhing, yes.” She snapped the locks open from her plastic box, upturning her girthy worms upon the ground. The worms, unlike malnourished counterpoints, flourished in Siobhan’s delicate compost. They were indeed larger and thicker, though the girth may have been slightly exaggerated. There was something…odd about them, however. A line from Wurmsten’s Pride and Wormjudice flashed in her mind: it was a truth universally acknowledged, that a single worm in possession of girth must be in want of a mate.

Siobhan shook her head, surely their passionate wiggles were nothing more than an eagerness to shed worm blood. “Go on, leanbh, or does the sight of my thick worms make you envious?”

--------

The Jade sauce came too late. Regan had done her best with the worms given her tardy start (with preparations, not… to everything else Siobhan surpassed her in), but her worms still looked mangled and pencil-thin. They took only occasional interest in apple slices and they kept squiggling into the sides of the container like they had no sense of place or orientation. But she had come here to win. And Siobhan was a boastful creature, wasn’t she? Her worms couldn’t be so grand as she claimed. They were probably just as grey, just as aimless.

“I agree to your terms. May the best worms win, cailleach.” There were no prizes or trophies in these wars of worms, only bragging rights. Siobhan would like the extra pin in her lapel, and Regan needed something she could surpass Siobhan in. Had the course of her life run smoother, she would have believed that needing something was enough to make it happen, but if anything, it created obstructions at every turn. Right. Confidence. She had Jade in her corner, even if she wasn’t present now. That was enough, right? Regan held onto that as she unceremoniously dumped her worms from their tin home. They collected by her feet, and she shook a little so stragglers could roll off her boots and join the rest of the squadron. “I was advised to read to them. They’re engorged with–” She would not admit she had read them Tana French “– harsh tales of the moors.”

Any fleeting confidence she held deflated when Siobhan dumped her worms on the ground, too. They were at least twice as thick as Regan’s, colored like cherry red lividity, and they squirmed with such vigor in comparison. Were… were her worms depressed? She glanced over to the limp mass at her feet, disappointed. It was the look her 1st grade art teacher used to give her when she handed in a drawing of a dead cow for the tenth time. But Regan would not abandon them; if no one believed in them, all bets of winning were off. She would take a line from Siobhan’s book and lob a competitive insult. That would inspire her worms. “I’ve seen better worms,” Regan said, arms crossed, as her stomach cramped from the lie. “Your worms are too soft. You have coddled them. They may have girth, but they know nothing of resilience.” She clenched a fist, fingernails against scar tissue. “Mine have thrived even under suboptimal conditions.” Her gaze sharpened as she met Siobhan’s eyes. “It’s no surprise. You’ve grown soft in your time away, too, haven’t you?”

The worms were in motion. Kind of. They were slow, groping for each other through the dirt in blindness. Siobhan’s took off first, faster than worms ought to move, but Regan’s were sluggish. She decided they were using their resources to fortify themselves. But as Siobhan’s came closer, her worms began wriggling anxiously, inching closer. They knew who their opponent was now. Good. Good. They tangled into a slimy cluster, two tense banshees casting shadows over them.

There was no blood. Where was the blood? They were entwined, were they not? “Are they…” The worms were wrapping up in each other with bulging clitellae, which was surely just an effort at strangulation. They didn’t have teeth. It was their way. “See how clever mine are, drawing yours in with a false sense of security.” Yes. Her worms might not have been pretty, but they were clever, weren’t they?

--------

It was the Austen that had done it. Why hadn’t Siobhan read to her worms about harsh moors? Why did she think Austen—and her worm counterpart, Wurmsten��would be good material for the worms? That was how they knew, that was why she was thinking of it; their girth made them in want of a mate. It seemed none of Austen’s—and Wurmsten, who claimed her novels were entirely unrelated to Austen—commentary on class and society were absorbed into their slimy bodies. That was why Siobhan read Austen—and Wurmsten, who might have only been known in one niche banshee community but made a healthy living of decaying flesh anyway—in fact: for the wit! The cunning! Certainly, nothing about the romance; it hardly occurred to her. The worms had taken the wrong message away. If only she had read them harsh tales of the moors.

Siobhan’s cheeks pinked like the worms’. “I was reading them The Art of War,” she lied through clenched teeth, swallowing back a bubble of acid. “This is simply what I’ve taught them: ‘a wise general makes a point of foraging on the enemy’. They are…foraging on the enemy.” Foraging could be one word for it, if the meaning was stretched enough, though the more obvious word burned on her tongue. The worms paired up, sealing wet, throbbing clittella to another’s body. Encasing themselves in mucus, Siobhan turned her head away as a particular white fluid bubbled out of the worms. Something was, in a way, being foraged.

“There is nothing false about this.” Siobhan leveled her gaze on Regan, careful to keep her eyes away from the foraging worms; her face blazed red. “Our worms have—Our worms are…” If she didn’t give it a name, if she didn’t say it, could she deny the truth? In a way, with a stretched definition and artistic liberties, they were foraging on the enemy. “It’s a new technique of war,” she said, “you wouldn’t know it; it’s not in whatever books about moors you’re reading. It is obviously very complex. The girth on my worms is at least eighty percent knowledge. Perhaps I am not soft. Perhaps you are just…hard.”

--------

The ground by Regan’s feet swelled with worms. Her worms, as sad and grey as they were (a few more weeks of Jade juice would have done the trick), had perked up to the presence of Siobhan’s vivacious worms, and were wiggling in response with more gusto than they had displayed in the entire time they had been with Regan. Not only did their swarming continue – it expanded – spreading over to Siobhan, a giant, pulsing mat of mucus and wriggling pink bodies. She had more or less abandoned the idea of this being worm cunning… attempting to believe something did not make it true, and all illusions in her life were undergoing a slow crumble as her departure neared.

Regan knew little about the secret mechanics of worm copulation, but that melding and fluid seemed reproductive in nature, and Siobhan, well… Regan didn’t know her cheeks could be that color. This was the woman who wore a turtleneck that was missing half its fabric. She had practically done a strip tease with a winter coat. She could blush? Regan studied the couplings, more certain by the second. “They’re… no, they’re definitely, uh…” She couldn’t quite say it either. But Siobhan was acting strange. For a banshee, hard was right. “Hm. I never thought I would hear you provide me with a compliment,” Regan said, raising a brow (she couldn’t look away from the worms, though; they were hypnotic). Unfortunately, it was not true – she was softer than Siobhan and in all the wrong ways. And it was the whole problem, the reason why she needed to go back. “Careful. You may convince me not to go with you, if I am hard. But then, your judgement is frail, isn’t it? You read your worms classic literature thinking it wouldn’t put… these notions in their small minds. Mine are only going along with it – they were poised for battle, then yours romanced mine.”

The ground sounded moist with worm love, like hands sliding into mayonnaise. And Worm Day was not the time for love. Regan’s fists clenched and she found her face growing hot, too. Fates, this really was happening. Was this really what was meant to occur? Her worms were fornicating with the enemy! What had gotten into them? Did that mean – was it actually love? It was beyond reason, like all love, as far as Regan could tell. Could it be, when they lacked the capacity for such emotion? That question made her belly ache (unclear why).

“We can’t separate them.” Regan spoke with certainty, but her voice was thick with something. She wasn’t sure where it came from (or the sentiment of not separating lovers). Some worm mucus probably got in there. She finally tore her eyes from the worm orgy and they landed on a very red Siobhan. “Can we agree on this? They remain together.” Was it worth throwing in that she meant the worms also could not be physically separated? Because that also seemed true. They had melded together, holding fast.

--------

“They are fucking.” Finally, Siobhan said it. “No,” Siobhan corrected herself, “they are making delicate, sensual worm love.” It was obvious to her, and her inability to look the worms directly in their anuses (they did not have eyes), that their passion extended beyond the realms of necessity; love was linking bodies together, stabbing each other with setae so the no new copulation could be committed, and then wiggling away to eat detritus. Worms knew love, of course they had felt a connection to the words of Jane Austen. “You are hard, maybe. Regan, you are very hard. You are erect with hardness. I cannot--I cannot deny the worms. Perhaps that makes me soft.” Siobahn turned around, shutting her eyes to the worms and the world. They possessed something she did not: love. And a slimy, pink, wiggling segmented body (but oh, how she wished for one).

Where had she gone wrong? From the beginning, it seemed. From loving her worms. From wanting a garden at all, from creating her compost bin. For wanting a life that wasn’t allowed to her. For imagining she might be a worm, writhing with girthy freedom in the dirt free to make love to wormever she pleased and eating as much manure as she wanted. She was a banshee; banshees didn’t do what they pleased. It was all wrong, all along: the war, the worms, the Regan. It was wrong to make innocent creatures act out her fantasies of power. They were worms and worms will do as they want: they will wiggle, they will secrete mucus, they will eat more than their weight each day. They did not have eyes, or legs, or arms, or lungs, but they could make love (they probably did not understand “love” at all, but Siobhan would only realize this after crying about her worms in the privacy of her house).

Siobhan turned around again, tears pooling around her brown eyes. “You’re right. You—child, baby, newborn infant with no knowledge—are right. We cannot separate these worms.” A war was defined by its binary nature; by winners and losers. The worms had won. Perhaps she had gone soft, perhaps the worms had changed her, perhaps it was the air and the occasion of worm day, but she didn’t care how emotional she came off. “If you love a worm…” She clutched at her slow-beating heart. “...let them go.” And she did, against her better judgment, love these worms.

“You…” Siobhan furiously wiped her eyes. Sniffling, she pointed at the other banshee. “...Will say nothing of this during our plane trip—and you will be coming with me. You will. But we have let these worms go—we are accepting a truce on this day. Another Worm Day, and there will be another, we will fight our worms again.” Siobhan sighed. “May your worms be less aroused by my girthy worms next time.”

And with that, the worms wiggled into the sunset.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuimhneacháin (28/04/24)

Tá 2 bhliain iomlán caite agus níl rud ar bith agus tá achan rud athraithe. D’athdhearbhaigh an t-aifreann comórtha - gnó brónach a raibh dhá líne speisialta ag gabháil leis chun an difir a dhéanamh idir é agus ceann rialta - m'amhras reiligiúnach. An uair seo ní dhearna mé iarracht fiú i ndáiríre labhairt le Dia i mo cheann le linn an ghiota ciúine sin tar éis an gChomaoineach a fháil.

Suí muid, peacadh, naomh agus laoch, in san tríú suíocháin deireanach, ar gcúl an chuid eile den teaghlach. Bhí b’fhéidir deichear eile ansin. Bhí sé ar siúil ar feadh 23 bomaite. Bhí cinéal cheo ag seoltóireacht i mo cheann. Corr uair, ligfidh an leanbh scread sásta aisti agus chuir sin aoibh ghrinn air m'aghaidh. Ach taobh amuigh de sin, sagairt sotalach agus cloigín dubhach, tá ciúnas sa séipéal.

Sílim, i gceann 20 bliain go mbeidh eaglaisí ag dúnadh achan áit mar ní théann aon duine níos mó ach amháin le haghaidh comaoineach agus baisteadh agus póstaí agus tórraimh. Níl go leor cultúr agam le fios a bheith agam faoi caidé a dtarlaíonn nuair a gheobhainn aindiachaí bás, ach tá mé cinnte go mbeidh an tsochaí ábalta déileáil leis.

Tá cuma mhaith ar an uaigh, fiú go raibh an aimsir go dóite fuar agus bhí teannas ait ag fás idir achan duine. Ach tá mise fós ábalta bheith ag magadh chomh maith le duine ar bith. Thug mé buail beag héadroime ar an dá thaobh fa choinne an bheirt agaibh nuair a bhí muid ag fhágáil - oíche mhaith, chodladh chomh samh.

Is ea an teach tar éis atá níos deacair - chan an teach baile, ní théim ansin níos mó. Ar dtús, tá na leanaí le mé a sheachaint, agus bia le tacht siar ar. Ach ansin bhí ciúnas millteanach idir muid uilig agus guí mé don chéad uair an lá sin go thiocfadh liom é uilig a fhágáil.

Tá muid caillte i do dhiaidh.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ag Briseadh An Ciúnas

by Michael Barrett with translations by Tom Malone

Bhíomar ar oileán beag insan fharraige t-Sín Theas, ag baint le baiste ár iníon , Regina. We were on a small island, in the South China Sea, for our daughter Regina’s baptism. Lá mór go deimhin, lá an bhaiste dúinn ar fad, for all of us, sin féin agus na gaolta, do réir an traidisiún.

Rud aisteach, a curious thing – níl aon ainm ar an oilean é féin! Ach tá trí bhaile ann: Oribi – an baile go dtagann mo bhean chéile Maria as, Dammay – áit ina bhfuil scata gaolta aici ann, agus Puro – áit ina bhfuil a thuilleadh gaolta aici. Mar gheall ar sin, we knew that a big crowd would travel by boat, go dtí an séipéal ar an mórthír – to the church on the mainland.

Ar a h-ocht a chlog ar maidin, our flotilla of colourful small boats left Oribi, ag tabhairt aghaidh ar an mórthír. We were heading towards the mainland. Bhí an t-ádh dearg orainn, mar bhí an fharraige ana chiúin an maidin sin. Bhíomar ábalta dul díreach treasna go dtí ár gceann scríbe – to our destination – an baile beag darb ainm Santa. So the journey didn’t take very long. Níor thóg an turas an iomad san ama. Ní minic a tharlaíonn sé chomh fuirist seo!

Ag Séipéal St. Catherine of Alexandria i Santa, bhí daoine bailithe, gaolta agus cairde ón mórthír . San phobal cruinithe bhi cairdeas chríost Regina, seacht duine deag acu! Seventeen godparents! Ins na Philippines is cairdeas chríost slí chun clainn a thabhairt le cheile. Ba duine de chairdeas chríost maor de Bhardas Santa. And the mayor arrived with four bodyguards! Agus gunnaí móra Kalashnikov acu!

Chuir an t-athair Josè Mabutas, an sagart paróiste, fáilte romhain ag an séipéal. Bhí an atmosféar i St. Catherine of Alexandria i Santa, lán de gáire – mar is gnáthach in ócáidí Filipino. Bhí Regina in a lámha ag Maria i rith an seirbhís agus ní bhféidir leis an leanbh í féin a iompar níos fearr. She couldn’t have behaved better – that is go dtí an uair a chaith an t-Athair Mabutas braon den uisce fuar ar a ceann beag! An nóiméad sin, bhí deire leis an gciúnas, because the child suddenly howled in protest – lig Regina Maria Victoria Queral Calano Barrett screach aisti! Agus screach sí arís, is arís eile! Dhein Maria a dícheall í a chur ina tost, ach lean an leanbh ag screacaigh gan stad! Bhain an maor an-ghreann as – the mayor was highly amused, agus dúirt sé “Tá an sacraimint ag obair cheana fein!” Ni amháin an maor, ach gháir an sagart paróiste chomh maith!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

In the Liturgical calendar, today is the Feast of the Holy Innocents or Lá Crosta na Bliana or the cross day of the year in Irish. The day was also known as ‘Lá na Leanbh’ (Day of the Children). In Irish tradition this day was seen as an unlucky day because it commemorated the murder of children by King Herod. In consequence, probably of the feeling of horror attached to such an act of atrocity,…

View On WordPress

#Cross Day of the Year#Feast Day#Feast of the Holy Innocents#King Herod#Lá Crosta na Bliana#Lá na Leanbh

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

In the Liturgical calendar, today is the Feast of the Holy Innocents or Lá Crosta na Bliana or the cross day of the year in Irish. The day was also known as ‘Lá na Leanbh’ (Day of the Children). In Irish tradition this day was seen as an unlucky day because it commemorated the murder of children by King Herod. In consequence, probably of the feeling of horror attached to such an act of atrocity,…

View On WordPress

#Cross Day of the Year#Feast Day#Feast of the Holy Innocents#King Herod#Lá Crosta na Bliana#Lá na Leanbh

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

In the Liturgical calendar, today is the Feast of the Holy Innocents or Lá Crosta na Bliana or the cross day of the year in Irish. The day was also known as ‘Lá na Leanbh’ (Day of the Children). In Irish tradition this day was seen as an unlucky day because it commemorated the murder of children by King Herod.

In consequence, probably of the feeling of horror attached to such an act of atrocity,…

View On WordPress

#Cross Day of the Year#Feast Day#Feast of the Holy Innocents#King Herod#Lá Crosta na Bliana#Lá na Leanbh

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

The Feast of the Holy Innocents | Lá Crosta na Bliana

In the Liturgical calendar, today is the Feast of the Holy Innocents or Lá Crosta na Bliana or the cross day of the year in Irish. The day was also known as ‘Lá na Leanbh’ (Day of the Children). In Irish tradition this day was seen as an unlucky day because it commemorated the murder of children by King Herod. In consequence, probably of the feeling of horror attached to such an act of atrocity,…

View On WordPress

#Cross Day of the Year#Feast Day#Feast of the Holy Innocents#King Herod#Lá Crosta na Bliana#Lá na Leanbh

0 notes

Text

Mairéad Ní Ghráda agus An Triail

le Deirdre Swain

Is é 2021 bliain chuimhneacháin céad bliain ó fuair Mairéad Ní Ghráda bás. Drámadóir, craoltóir, múinteoir agus gníomhaí ar son na Gaeilge ab ea í. Is fearr aithne uirthi as a dráma, An Triail. Rugadh Mairéad i gCnoc a’ Daingin i gCill Mháille, Co. an Chláir ar 23 Nollaig 1896. Bhí Gaeilge thart timpeall uirthi i gcónaí agus í ag fás aníos. Feirmeoir agus cainteoir dúchais ab ea a h-athair, agus b’uaidh a fuair sí a grá don Ghaeilge agus a tiomantas ar feadh an tsaoil d’athbheochan na Gaeilge. Bhí sé báite sa traidisiún béil, agus bhíodh sé ag aithris an dáin, Cúirt an Mheánoíche le Brian Merriman go minic. Bhí Mairéad éadócasach i dtaobh na teanga Gaeilge. Dúirt sí uair amháin go raith áthas uirthi nár bhain sí leis an nglúin a chaillfeadh an Ghaeilge go deo.

Theastaigh óna tuismitheoirí go gcuirfeadh sí deireadh lena cuid oideachais tar éis na bunscoile ionas go raghadh sí ag obair ar an bhfeirm. Níor tharla sé seo; ina ionad, chuaigh sí go dtí meánscoil in Inis. Bhuaigh sí roinnt duaiseanna mar scoláire, agus bronnadh scoláireacht Chomhairle Contae uirthi go Coláiste Ollscoile Bhaile Átha Cliath, áit ar ghnóthaigh sí BA sa Ghaeilge, Bhéarla agus Fraincis agus MA sa Ghaeilge. Bhí sí i gCumann na mBan agus i gConradh na Gaeilge fad is a bhí sí ann. Cuireadh i bpríosún í uair amháin mar go raibh sí ag díol bratacha poblachtánacha ar Shráid Grafton, rud a mbíodh sí ag déanamh grinn de caoga bliain ina dhiaidh. D’oibrigh sí mar mhúinteoir agus ansan mar rúnaí príobháideach do Earnán de Blaghd, TD Chumann na nGael i gcéad Dáil an tSaorstáit nua. Lean sí uirthi ag obair dó i rith an Chogaidh Chathartha nuair a bhí sé ina Aire Airgeadais. Phós sí Risteard Ó Cíosáin, garda sinsearach, sa bhliain 1923, agus bhí beirt clainne acu, Séamas agus Brian. I 1926, thosnaigh an chéad stáisiún raidió in Éirinn, 2RN (a dtabharfaí Radio Éireann air níos déanaí), ag craoladh. Fostaíodh Ní Ghráda mar eagarthóir mná ar 2RN, ag cur cláracha do mhná agus do pháistí le chéile. Rinneadh príomh-chraoltóir an stáisiúin di i 1929. B’í an chéad chraoltóir mná in Éirinn agus sa Bhreatain agus b’fhéidir san Eoraip í. D’oibrigh sí mar chraoltóir ar feadh naoi mbliana.

Bhí baint ag Ní Ghráda le téacsleabhair scoile a scríobh do Phádraig Ó Siochrú (An Seabhac, mar a ghlaodh air), a bhí i roinn na leabhar scoile de Chomhairle Oideachais na hÉireann. Scríobh sí alán téacsanna oideachais, Progress in Irish san áireamh. Bhí sí ina h-eagarthóir ag de Brún agus Ó Nualláin, foilsitheoir téacsleabhair scoile. Dhein sí léirmheas ar fhoclóir Gaeilge De Bhaldraithe chun cabhrú le múinteoirí. Bhí sí chomh díograiseach gur lean sí uirthi ag cur leabhair scoile ar téip nuair a bhí sí breoite san ospidéal.

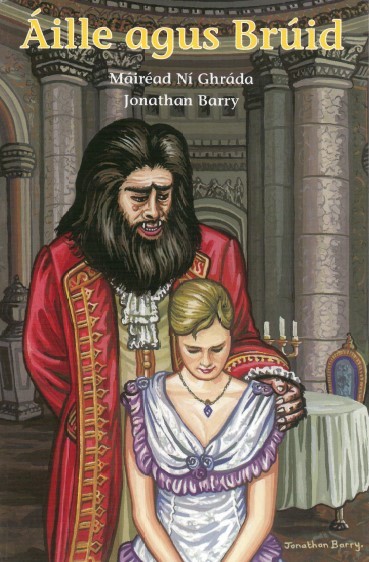

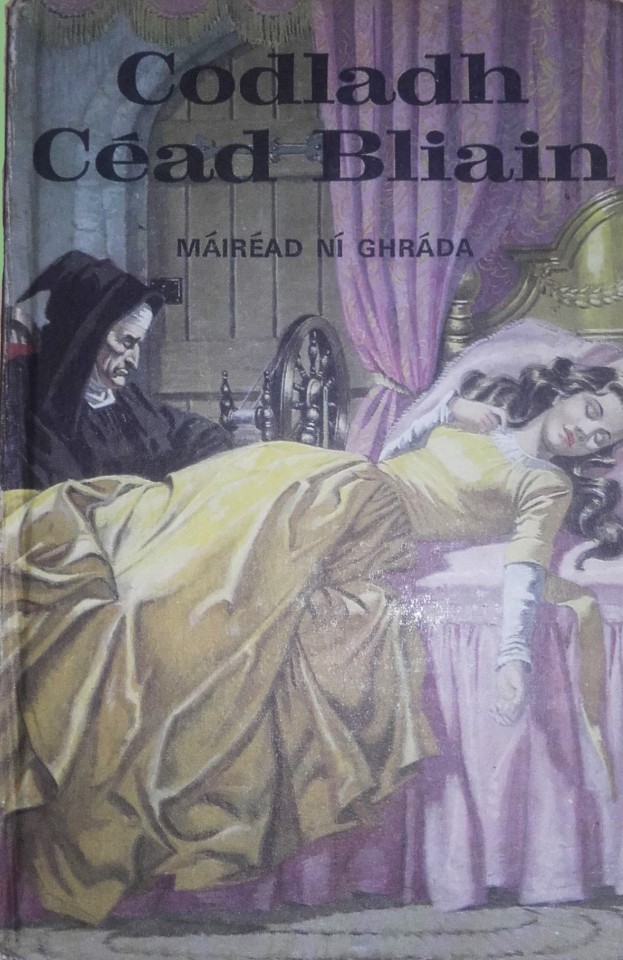

Bhí an-shuim aici i riachtanaisí oideachais leanaí, agus thuig sí aigne daoine óga go han-mhaith. Tá sé seo soiléir óna drámaí. Scríobh sí drámaí scoile a bhí bunaithe ar na scéalta Fiannaíochta, ar an miotaseolaíocht, ar an mBíobla, ar scéalta Aesop. D’aistrigh sí Peter Pan go Gaeilge (Tír na Deo). Scríobh sí leagain Ghaeilge álainne de scéalta sí ón sraith “Bóin Dé” nó na “Ladybird Books”. Chabhraigh s�� seo le litearthacht a leathadh sa Ghaeilge. Samplaí dos na leabhair seo do pháistí a scríobh sí as Gaeilge ná: Na trí Bhéar (Goldilocks and the Three Bears), Codladh Céad Bliain (Sleeping Beauty), Luaithríona (Cinderella), Áille agus Brúid (Beauty and the Beast), Rápúnzell (Rapunzel) agus Seán agus an Gas Pónaire (Jack and the Beanstalk).

Bhí grá ar leith ag Ní Ghráda don drámaíocht. Bhí droch-chaoi ar dhrámaíocht na Gaeilge agus í ag tosnú ag scríobh, ach d’athraigh sí é seo; bhí suim ag daoine ina drámaí fiú muna raibh aon Ghaeilge acu. Bhí sí ag cur Gaeilge ar fáil do dhaoine i slí taitneamhach tríd an amharclann. Rinne sí éacht thar na bearta ar son na drámaíochta sa teanga Gaeilge. Scríobh sí aon bhunsaothar drámaíochta déag i rith a saoil – níos mó ná aon dhrámadóir eile sa Ghaeilge. I 1933, bronnadh gradam Amharclann na Mainistreach ar a dráma, Mícheál. Bhí an dráma sin bunaithe ar scéal Tolstoy, Michael. Scríobh sí a céad dráma, Uacht, fad is a bhí sí ag múineadh Gaeilge sa Choláiste Cócaireachta i gCill Mochuda. Dá mic léinn é i ndáiríre, ach léirigh Mícheál Mac Liammóir é in Amharclann an Gheata.

Scríobh Ní Ghráda drámaí cumhachtacha a d’inis an fhírinne faoi ghnéithe de shaol na hÉireann ag an am. Phléigh siad fadhbanna na linne trí Ghaeilge. Bhí ar a cumas páirteanna fiúntacha a cheapadh do mhná ina drámaí, go háirithe do mhná óga, rud annamh i gcás dhrámadóirí na hÉireann, lasmuigh de Sheán O’Casey. Chuir a drámaí míchompórd ar dhaoine, mar phléigh siad ábhair ná raibh ceadaithe. Bhí téamaí iontu go raibh faitíos ar dhaoine aghaidh a thabhairt orthu, téamaí mar cás na mban a raibh leanbh acu lasmuigh de chuing an phósta, agus scéal na bpolaiteoirí lofa. Bhí sí go mór chun tosaigh ar lucht a linne.

Is é An Triail an dráma is iomráití a scríobh Ní Ghráda. Tá sé inchurtha leis An Giall le Breandán Ó Beacháin mar cheann dos na drámaí is rathúla sa teanga Gaeilge. Is dráma é atá an-chuí faoi láthair, i mbliain a foilsíodh Tuarascáil Deiridh an Choimisiúin Imscrúdúcháin ar Árais Máithreacha agus Naíonán. Tá sé tráthúil chomh maith mar go bhfuiltear ag plé cearta pháistí uchtaithe agus cearta a máithreacha faoi láthair, agus an éagóir a deineadh orthu. Cuimhne ar chailín bocht a díbríodh as Cill Mháille fadó agus gur ligeadh don bhfear dul saor ó mhilleán a chuir i gceann Mhairéid An Triail a scríobh. Chreid sí gur chóir go mbeadh comhoibriú idir dhrámadóir agus foireann amharclainne agus nach bhfuil i scríbhinn ach creatlach dráma; go bhfuil feabhsú le déanamh ag an léiritheoir air. Mar shampla, dhein sí athscríobh ar phíosaí de An Triail faoi threoir an léiritheora, Tomás Mac Anna, an deireadh san áireamh.

Is dráma tragóideach é An Triail a thugann cuntas ar an tslí a gcaitear le cailín óg, Máire, a mbíonn caidreamh aici le fear pósta agus a éiríonn torrach dá bharr. Teipeann a máthair agus a beirt dearthár uirthi. Bíonn a máthair buartha faoi thuairimí na gcomharsana, ach ní bhíonn imní uirthi faoi leas a h-iníne ná leas a gar-iníne. Níl trua ag éinne do Mháire ná ní chabhraíonn éinne léi seachas Mailí, a thugann dídean di, agus “Aturnae 2” ag a triail. Tugtar breith uirthi agus cáintear í. Ní theastaíonn ó athair a h-iníne an leanbh a fheiscint fiú. Ar deireadh, maraíonn sí í féin agus a leanbh, go bhfuil an-chion aici uirthi. Deireann Máire gur mharaigh sí a h-iníon mar gur cailín í; gur shaor sí í ó phian na mná nuair a mharaigh sí í. Tá an téama seo ar fud an dráma; cloistear guth Mháire á rá ag an dtús agus ag an deireadh. Is é an cheist a fhiafraítear sa dráma ná, “Cén fáth a dtárlaíonn rudaí mar seo in Éirinn?” Dúirt Tomás Mac Anna, an léiritheoir, go raibh an dráma seo go mór chun tosaigh ag plé ceist “Saoirse na mBan”. I slí, bhí Éire féin á chur faoi thriail ag an drámadóir. Thaitin An Triail go mór le Harold Hobson ón nuachtán an Times i Londain, agus mhol sé go h-ard é, cé nach raibh focal Gaeilge aige.

Léiríodh An Triail don gcéad uair in Amharclann an Damer i rith Féile Drámaíochta Bhaile Átha Cliath i 1964. Go gairid ina dhiaidh sin, d’aistrigh Ní Ghráda an dráma go Béarla, agus i 1965, léiríodh an leagan Béarla, On Trial, in Amharclann an Eblana. Cóiríodh An Triail don teilifís ansan, agus cuireadh isteach é i bhFéile Teilifíse Bheirlin 1965. B’annamh cláracha teilifíse á gcóiriú as drámaí i nGaeilge, ach b’amhlaidh do An Triail. Foilsíodh an t-aistriúchán Béarla i 1966.

Fuair an dráma seo ardmholadh ós na léirmheastóirí, ach bhí sé conspóideach nuair a chuireadh ar stáitse ar dtús é. Chuir an smaoineamh go rabhamar go léir ciontach a bheag nó a mhór san easpa carthanachta, isteach ar roinnt daoine: ionsaíodh an dráma toisc é a bheith “mímhórálta”. Léiríodh An Triail don gcéad uair ar 22 Meán Fomhair 1964, trí lá tar éis do Mhichael Viney an mhír dheireanach dá sraith altanna dar theideal, “No birthright” a fhoilsiú san Irish Times. Fiosrúchán criticeach ab ea an tsraith seo ar an tslí a chaitheadh le máithreacha in Éirinn nach raibh pósta. In alt amháin, deireann Viney go ndúirt máthair Éireannach amháin leis nár theastaigh uaithi go bhfillfeadh a h-iníon ar Éirinn agus go raibh a muintir agus a tír náirithe aici. In alt eile, deineann sé trácht ar chailín nach bhfuil pósta a insíonn dá máthair go bhfuil sí torrach. Dúirt sí nach raibh aon rud ag déanamh tinnis dá máthair ach tuairimí na gcomharsana. Cé go bhfuil sé deacair é seo a shamhlú inniu, taispeánann na cuntais seo go bhfuil léiriú cruinn sa dráma An Triail ar na dearcaí claonta agus cruálacha a bhí ag daoine ag an am sin i dtaobh máithreacha nach raibh pósta, agus ar an mbuairt a bhí orthu faoi thuairimí na gcomharsana.

Chaith Mairéad Ní Ghráda an dá bhliain dheireanacha dá saol san ospidéal. Fuair sí bás ar 13 Meitheamh 1971.

Tá cóip den leagan Béarla den dráma, On Trial, le fáil sa Leabharlann Tagartha. Tá leabhar ann leis faoi Mhairéad Ní Ghráda agus faoi dhrámadóirí eile a scríobh as Gaeilge: an teideal atá ar an leabhar seo ná An underground theatre: major playwrights in the Irish language, 1930-80 le Philip O’Leary. Is féidir breathnú ar na leabhair seo sa Leabharlann Tagartha nuair a ath-osclaíonn sé.

Tagairtí

Leabhair

-Breathnach, D. agus Ní Mhurchú, M. (1986). 1882-1982: Beathaisnéis a haon. Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta.

-Ní, Ghráda, M. (c1978). An Triail/Breithiúnas: Dhá Dhráma. Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair.

-Ní Mhurchú, M. agus Breathnach, D. (1999). 1782-1881: Beathaisnéis [Maille le Forlíonadh le 1882-1982 Beathaisnéis agus le hInnéacs (1782-1999)]. Baile Átha Cliath: An Clóchomhar Tta.

-Titley, A. (2010). Scríbhneoirí faoi chaibidil. Baile Átha Cliath: Cois Life Teoranta.

Altanna ón Idirlíon

-Clare County Library (2021). Mairéad Ní Ghráda (1896-1971). 5 March. Available at: https://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/people/nighrada.htm (Accessed: 5 March 2021).

-Irish Theatre Institute (2021). Ócáid Chomórtha: A Celebration of Máiréad Ní Ghráda: Mairéad Ní Ghráda – Biography. 5 March. Available at: https://www.irishtheatreinstitute.ie/event.aspx?t=mir%C3%A9ad_n%C3%AD_ghrda&contentid=9289&subpagecontentid=9297 (Accessed: 5 March 2021).

-Irish Theatre Institute (2021). Ócáid Chomórtha: A Celebration of Máiréad Ní Ghráda: Production History. 5 March. Available at: https://www.irishtheatreinstitute.ie/event.aspx?t=an_triail_|_on_trial___production_history&contentid=9289&subpagecontentid=9302 (Accessed: 5 March 2021).

-Irish Theatre Institute (2021). Ócáid Chomórtha: A Celebration of Máiréad Ní Ghráda: Social Context. 5 March. Available at: https://www.irishtheatreinstitute.ie/event.aspx?t=social_context&contentid=9289&subpagecontentid=9303 (Accessed: 5 March 2021).

1 note

·

View note