#Kheda Barech Defai

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#movies#polls#where is the friend’s house?#where is the friends house#where is the friends house?#where is the friend’s house#80s movies#abbas kiarostami#babek ahmed poor#ahmed ahmed poor#kheda barech defai#requested#have you seen this movie poll

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Where Is the Friend’s Home? (Kiarostami, 1987)

#where is the friend's home#where is the friend's house#where is my friend's house#خانه دوست کجاست#Abbas Kiarostami#kiarostami#Babek Ahmedpour#Ahmed Ahmedpour#Kheda Barech Defai#Iran Outari#Mohammad Hossein Rouhi#cinema#film#iran#persia

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picked up the Criterion boxset of the Koker trilogy.

10.19.19

#watched#film#letterboxd#where is the friend's house#abbas kiarostami#criterion collection#babek ahmed poor#ahmed poor#kheda barech defai#iran outari#ait ansari#sadika taohidi#biman mouafi

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kheda Baresch Defai as the teacher in Where is the Friends Home? (1987). Kheda’s only other film credit is Abbas’ Kiarostomi’s Through the Olive Trees (1994).

0 notes

Text

Realism, Morality and Care in Where Is the Friend’s House?(Abbas Kiarostami, 1987)

Sandra E. Lim July 2020 CTEQ Annotations on Film Issue 95

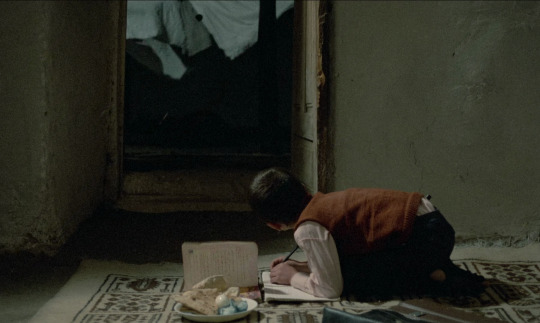

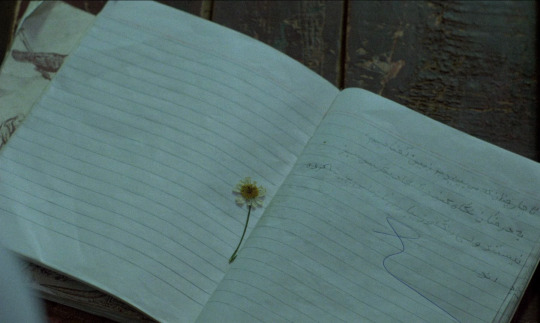

Kahne-ye doust kodjast? (Where is the Friend’s House?, 1987), is the first of three interrelated films in Abbas Kiarostami’s “Koker trilogy”, named after the northern Iranian village where the films are set. The film draws its title from a mystical poem by the venerated Iranian poet and painter Sohrab Sephehri (1928–1980), and echoes the equivocal journey undertaken in the poem.1 In doing so, Where Is the Friend’s House? also reveals a Piagetian universe in which children are seen to navigate the rules and authority of adults, out of a sense of obedience and fear of punishment. Yet, Kiarostami also constitutes the children of Where is the Friend’s House? with an overriding sense of morality, as evidenced in the figure of eight-year-old Ahmad (Babak Ahmadpour), who mistakenly takes his friend Mohammad Reza Nematzadeh’s (Ahmed Ahmadpour) notebook home after school one day. The revelation of this mistake subsequently fuels the imperative to save his friend from the fate of the overly strict teacher’s (Kheda Barech Defai) harsh punishment, setting him in motion on an obstacle-laden journey to return the notebook, zigzagging through landscapes, maze-like alleyways and a host of unhelpful people along the way.

While the hero’s journey is a simple premise, Kiarostami’s style of realism is characterized by an economy of form, which is deceptively simple — especially in the structuring device of asking for directions, the answers to which are never straightforward. In this way, Kiarostami asks the viewer to interact with the narrative, to pick up and weave its threads. For example, near the beginning of his search Ahmed comes upon a classmate named Morteza, who he enlists for directions and help. Earlier in the day, the boy was scolded for being under a desk and not paying attention, and when the teacher asked why, the boy simply replied that his back hurt. The character is soon forgotten until Ahmed encounters his classmate again in Poshteh, the village where his friend is said to live. Morteza is seen retrieving heavy containers laden with milk, and the puzzle of why his back hurt is immediately apparent. Although Morteza cannot accompany Ahmed, as the milk must be tended to, he offers help in the form of unconventional directions to Nematzadeh’s cousin’s neighbourhood: “…in Khanevar, up the hill, there’s a staircase in front and a blue door right by a bridge.” Through this exchange, we also infer about the lives of the children, and the difficulty of doing homework — a subject picked up in Kiarostami’s subsequent documentary, Homework (1989).

In fact, the Iranian film scholar Hamid Naficy attributes Kiarostami’s idiosyncratic style of realism to a confluence of personal, historical/political and institutional factors.2 For example, the personal observations of Kiarostami’s son Ahmad reveal that his father’s method of realism was not informed by knowledge of film or copying other directors, but instead by everyday life, and in the case of Where is the Friend’s House? through his own interactions with his young son Bahman. Kiarostami also developed a style of non-acting, in which he enlisted children from the village of Koker to improvise and react to real situations “as a living thing.” As Ahmad Kiarostami details, the scene where Nematzadeh gets into trouble for not doing his homework was a result of the boys being given a photograph, which was placed in Nematzadeh’s notebook, and told that the teacher would be very mad if he found it. When class begins and the teacher starts checking homework, Nematzadeh (or perhaps Ahmed, the boy who plays him), breaks down into tears under the real-life pressure of failing to produce his homework for grading, having to conceal the photograph that is hidden within the notebook.3 In this way, Kiarostami’s style of realism also moves between documentary and fiction.

While Where is the Friend’s House? is not an overtly political film, it was made during Kiarostami’s early- to mid-career, spanning the turmoil of two political regimes: the rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919–1980), and the Iranian revolution of 1979, which brought the Shia Islamic cleric Ayatollah Khomeini (1902–1989) into power. Under the secular monarchist and authoritarian rule of the Shah, and the Westernization of Iranian culture, Kiarostami got a start in commercial art and advertising, becoming known for his “slick and stylish” TV commercial productions.4 It was in advertising, the Iranian film scholar Hamid Naficy observes, that Kiarostami acquired “brevity and precision of expression.”5

Moreover, the Iranian filmmaker Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa remembers first-hand that, while many of his contemporaries went into exile during 70s and 80s, Kiarostami stayed and “kept a low profile.”6 During this period, Kiarostami helped set up and establish the government film production unit known as the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Youths, or Kanun. The development of Kanun was a rich period of output in Kiarostami’s career. As Rosenbaum observes, Kanun became a breeding ground and film school for experimental filmmakers. In this context, Kiarostami helped train a new generation of artists, both women and men, and it was also during this time that Kiarostami developed a pedagogical style of filmmaking around the subject of children, as epitomized in Where is the Friend’s House?, which promoted didactic messages such as loyalty and “cooperation over conflict” — and in the case of Where is the Friend’s House?, the difficulty of doing the right thing.7

According to Naficy, Kiarostami worked in the film unit for more than two decades as a “civil servant” and was not particularly well regarded by his more politically charged contemporaries, who condemned his output as politically “compromised,” in working under the aegis of the Islamic regime. Nevertheless, Naficy asserts that the films of this period offered artful and implicit “critiques of Iranian culture and society.”8 Adding to this, Where is the Friend’s House? can also be regarded as a simple antidote to authoritarian rule, in promoting the practice of morality and care towards and for one another.

• • •

Kahne-ye doust kodjast? (Where is the Friend’s House?, 1987 Iran 83 mins)

Prod. Co: Janus Films and The Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children Prod: Ali Reza Zarrin Dir:Abbas Kiarostami Scr: Abbas Kiarostami Phot: Farhad Saba Mus: Amine Allah Hessine Ed: Abbas Kiarostami Snd Ed: Changiz Sayad Snd Rec: Jahangir Mirshekari, Asghas Shahverdi, Behrouz Moavenian Art dep: Reza Nami Cos: Hassan Zahidi Prod Ass: Nasser Zeraati

Cast: Babak Ahmadpour, Ahmad Ahmadpour, Kheda Barech Defai, Iran Outari, Ait Ansari, Biman Mouafi

Endnotes:

Jonathan Rosenbaum & Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, “A Dialogue Between the Authors” in Contemporary Film Directors: Abbas Kiarostami, second expanded edition, ed. James Naremore, Justus Nieland and Jennifer Fay (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), p. 90. ↩ Hamid Naficy, “All Certainties Melt into Thin Air: Art-House Cinema, a Postal Cinema,” in A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012), p. 178. ↩ The Criterion Collection, “Ahmad Kiarostami,” Through the Olive Trees, Disc 3, DVD. Directed by Abbas Kiarostami, 1994 (New York: Criterion Collection, 2018). ↩ Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami, p. 101. ↩ Hamid Naficy, “All Certainties Melt into Thin Air: Art-House Cinema, a Postal Cinema” in A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Vol. 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), p. 179. ↩ Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, “Abbas Kiarostami” in Contemporary Film Directors: Abbas Kiarostami, second expanded edition, ed. James Naremore, Justus Nieland and Jennifer Fay (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 47. ↩ Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami, pp. 8–10. ↩ Naficy, p. 179. ↩

0 notes

Photo

Where Is My Friend’s Home? (1987, Iran)

Alternatively translated to Where is the Friend’s Home?, Abbas Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home? (as I shall refer to it for the duration of this write-up) is the first film of the accidental Koker trilogy. This refers to the fact Kiarostami shot three films in the city of Koker, later adding And Life Goes On (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994) - the designation of the Koker trilogy is thanks to academics and critics and not Kiarostami himself. Koker, which is located in rural Northern Iran, would be an unlikely place for Kiarostami to have his name become known not just in restrictive post-Revolutionary Iran, but the film world as a whole. Many would not think Iran as a hotbed of quality cinema - especially in the late 1980s - but Kiarostami and his fellow Iranian directors had ways to get around the religious-based censors. One such way that was popular was to shoot a film about children being children. This would be a time in which Iranian directors excelled in depicting children as honestly as most anyone ever could.

It begins with a simple all-boys classroom as the boys are roughhousing around before class. The teacher (Kheda Barech Defai) comes in and checks each of his students’ homework. One of the boys, Mohamed Reda Nematzadeh (Ahmed Ahmed Poor) has not done his homework in his notebook as the teacher has requested from him too many times. Frustrated with himself, Mohamed attempts to tell the teacher he had simply forgotten to bring his notebook home while playing with his cousin (who is also in the class) at his cousin’s house the night before. The excuse is dismissed and the teacher warns Mohamed that if Mohamed repeats this mistake, he will be expelled. Now the film stars Ahmed (Babek Ahmed Poor) because - as dumb luck would have it - he accidentally takes both his notebook and Mohamed’s notebook when they are dismissed from class for the day. He discovers the mistake only after going home, is concerned for his friends, and appeals to his mother to run over to the nearby village where Mohamed lives. His mother steadfastly refuses to let him go until he has done his own homework and the household chores. Soon after, Ahmed speeds off, asking the residents from the other neighborhood where Mohamed lives.

And that’s it. That’s the plot and that is the conflict. It sounds minimal compared to whatever convoluted action films all of us are subjected to nowadays, but Kiarostami certainly has a sympathy and understanding with his characters that allows us to connect to Ahmed and Mohamed. Also aiding this sense of familiarity is the fact that the cast for Where Is My Friend’s Home? is comprised of nonprofessional actors from top to bottom. Kiarostami recruited the residents of Koker and the nearby towns to star in roles as if this was a documentary, not a narrative film. When not expressly talking to Ahmed, it seems as if everybody else is going about their natural everyday routine - we get the sense that these folks have been to the market, playing board games, and talking to their friends in these specific settings thousands of times before. It almost makes one forget that this is a film, not real life. But when the adults and other children are talking to Ahmed, the acting does feel a little forced and a tad wooden. But that’s okay - all of their other action’s and Kiarostami’s helming of the film make up for whatever objections one might have about the acting.

To best enjoy the film, it’s best to take off your thespian lens for a moment and instead dig back into your primary school-age memories. We all know what it is like to be in constant trouble with a teacher or perhaps a parent, to be given the sternest of last warnings by that same person, and to find ourselves breaking our promise in not screwing things up again. The humiliation and embarrassment of being expelled from school over such small mistakes (I myself can be very absent-minded on these small things) is crushing to kids of this age. Combined with generational expectations - especially in the area of parental, grandparental, and pedagogical expectations - the film’s gentle humor pokes at Ahmed and his mother’s continual insistences as well as his grandfather’s bemoaning how, back when he was a child, children were brought up in the best way. A children’s film is no place for sweeping social commentary and damning condemnations and thank goodness there is none of that here. Elders will be elders as parents will be parents as children will be children. One noteworthy thing about the scene after Ahmed is talking to his grandfather is the fact that none of the adults are listening to Ahmed’s claims for help. Ahmed, with a conscientiousness and courtesy to a person whose address is unknown to him, is showing more kindness than all of the useless adults surrounding him.

There are also moments of simple aesthetic beauty. Ahmed’s run to the neighboring village to bring back Mohamed his notebook is a series of long takes and few cuts - it is almost as if we were running along that zigzagging dirt path with him. This extends and heightens the little tension there is and only makes the audience root for him more. If anything, long takes have always been a source of tension-building and cinematographer Farhad Saba and Kiarostami’s editing (he also wrote the screenplay) take these extensions as long as they can hold an audience’s attention, but not too long as to lull the least patient ones to sleep. Despite a minimal amount of non-diegetic music to fill in the aural gaps, this is a film that keeps most anybody who cares to see Where Is My Friend’s Home? watching. The eighty-three minute runtime feels far less than that as we come to understand Ahmed through his selflessness and his neighbors, friends, and family through their small moments.

There is a tragic note behind this production. On June 21, 1990, a magnitude 7.4 earthquake struck northwestern Iran, killing 50,000 civilians in its wake. Kiarostami, hearing that the earthquake hit Koker very hard, rushed to the area, only to learn that many of the cast members of Where Is My Friend’s House? were killed.

This is a true children’s film - one free of the precocious cynicism and witticisms Hollywood has impressed upon audiences in recent years. No American kid in early-mid elementary school has a brain that can unleash verbal takedowns so often and so fatal… so what a refreshing breath of clean air is Where Is My Friend’s Home?. Its timelessness, as more people around the world come to grips that cinema is not only Hollywood, Bollywood, and Europe, will soon be visited by more and more people as Kiarostami’s efforts have been greatly underseen and underappreciated.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating.

#Where Is My Friend's Home?#Abbas Kiarostami#Babek Ahmed Poor#Ahmed Ahmed Poor#Kheda Barech Defai#Farhad Saba#TCM#The Story of Film: An Odyssey#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes