#Khalsa Advocate

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Guru Gobind Singh Ji's Legacy and the Creation of the Khalsa

Introduction

Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the tenth Sikh Guru, left an indelible mark on the history and spirituality of Sikhism through the creation of the Khalsa in 1699. This pivotal event not only redefined the Sikh identity but also unified the community under a shared set of spiritual and moral commitments. The formation of the Khalsa represented a radical call to arms for justice, equality, and devotion, emphasizing the warrior-saint ethos that is central to Sikhism. This article explores the historical events leading to the establishment of the Khalsa and its profound impact on the Sikh community.

The Formation of the Khalsa

The Khalsa was established during the Vaisakhi festival at Anandpur Sahib, where Guru Gobind Singh Ji called upon his followers to dedicate themselves fully to the Sikh faith and its values. This transformative moment came against a backdrop of religious persecution and political instability in the region. By initiating the first five Sikhs, known as the Panj Pyare (the Beloved Five), into the Khalsa, Guru Gobind Singh Ji set forth a new standard of conduct for Sikhs, one that required maintaining unshorn hair, carrying a Kirpan (sword), and adopting other articles of faith that symbolize commitment and courage.

Impact on Sikh Identity and Unity

The establishment of the Khalsa was a unifying force among Sikhs, creating a distinct identity that combined spiritual purpose with martial prowess. The Khalsa’s ethos of Chardi Kala (eternal optimism) and Sarbat da Bhala (welfare of all) developed a strong sense of community and purpose, driving the Sikh community to advocate for justice and protect the oppressed, regardless of their religious or social background. Over the centuries, this has not only helped preserve the faith during times of adversity but has also inspired countless acts of bravery and kindness among Sikhs around the world.

ConclusionThe legacy of Guru Gobind Singh Ji and the Khalsa continues to resonate deeply within the Sikh community. It stands as a symbol of the power of faith and righteousness in upholding human dignity and justice. Today, organizations like the Dasvandh Network embody the spirit of the Khalsa by directing resources towards the betterment of humanity and upholding the values of Sikhism. To support or learn more about how the Dasvandh Network promotes these timeless principles, visit Dasvandh Network.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sikhism: The Religion of Unity and Courage – A Journey of Spirituality and Justice

Sikhism, one of the world’s youngest religions, originated in the 15th century in Punjab, a region that is now divided between India and Pakistan. Founded by Guru Nanak, Sikhism rejects the caste system, idolatry, and ritualism, instead promoting equality, social justice, and direct devotion to one God. With approximately 25 million followers, it is the fifth largest religion in the world. This article explores the origins of Sikhism, its core doctrines and practices, and how it continues to inspire its followers around the world.

The Origins of Sikhism: The Teachings of Guru Nanak Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak (1469-1539), who was born at a time of great social and religious turmoil in the Indian subcontinent, where Hinduism and Islam coexisted, often in conflict. Guru Nanak was a spiritual thinker deeply influenced by these traditions, but he believed in a new spiritual approach that transcended religious divisions.

At the age of 30, after a mystical experience while bathing in the Kali Bein River, Nanak emerged with a clear message: “There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim,” emphasizing the unity of all human beings and devotion to one God. He spent the rest of his life traveling across the Indian subcontinent, preaching a message of love, equality, and selfless service, attracting followers who would become the first Sikhs (disciples).

The Ten Gurus and the Establishment of Sikhism Following Guru Nanak, Sikhism was guided by a succession of nine Gurus, who consolidated and expanded the teachings of the faith. Each Guru played a crucial role in the spiritual, social and military development of the Sikh community:

Guru Angad (1504-1552): Created the Gurmukhi script, used to record sacred teachings. Guru Amar Das (1479-1574): Instituted the practice of "Langar", the community kitchen that provided free meals to all, regardless of their religion or social status. Guru Ram Das (1534-1581): Founded the holy city of Amritsar, which became the spiritual center of the Sikhs. Guru Arjan (1563-1606): Compiled the Adi Granth, the sacred text of Sikhism, and oversaw the construction of the Golden Temple in Amritsar. Guru Hargobind (1595-1644): Introduced the concept of Miri and Piri, representing temporal and spiritual authority, and militarized the Sikh community to defend itself from persecution. Guru Har Rai (1630-1661) and Guru Har Krishan (1656-1664): Continued the mission of peace and service, even in times of increasing conflict. Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621-1675): Defended religious freedom against Mughal oppression, sacrificing his life to protect the right of all to practice their faith. Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708): Founded the Khalsa, a brotherhood of baptized Sikh warriors who advocated justice and equality. He declared that after him, the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy book, would be the eternal spiritual guide of the Sikhs. Fundamental Doctrines and Practices of Sikhism Sikhism is based on the belief in one God, known as Waheguru, who is formless, omniscient, and accessible to all. The core teachings of Sikhism can be summarized in three tenets:

Naam Japna (Meditation on the Name of God): Sikhs are encouraged to meditate and constantly remember God in their daily actions.

Kirat Karni (Honest Work): Earn an honest living and contribute to the well-being of society.

Vand Chakna (Sharing with Others): Practice charity and share one’s resources with those in need.

In addition to these tenets, Sikhs follow the Five Ks, symbols of identity and spiritual commitment:

Kesh (Uncut Hair): Represents acceptance of one’s natural God-given form.

Kara (Steel Bracelet): Symbolizes eternity and commitment to good deeds.

Kanga (Wooden Comb): Denotes cleanliness and order.

Kachera (Cotton shorts): A symbol of modesty and self-control. Kirpan (Small sword): Represents the fight for justice and the defense of the oppressed. The Khalsa and the Warrior Spirit of Sikhism The founding of the Khalsa by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699 was a turning point for Sikhism. Guru Gobind Singh instituted an initiation ritual in which followers pledged to uphold justice, protect the weak, and live a life of purity and spiritual discipline. Members of the Khalsa adopted the name "Singh" (lion) for men and "Kaur" (princess) for women, reflecting the equality and dignity that the faith advocates.

The Khalsa played a key role in resisting Mughal oppression and later, the Afghan invasions, establishing the Sikhs as a powerful military force in northern India. This spirit of fighting for justice remains alive in modern Sikhs, who continue to uphold the ideals of equality, freedom and courage.

The Guru Granth Sahib: The Living Scripture The Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book, is more than a collection of scriptures; it is considered the eternal guru of the Sikhs. Originally compiled by Guru Arjan, the text contains hymns and poetry from various Gurus, as well as Hindu and Muslim saints, reflecting the inclusive and universalist nature of Sikhism.

The Guru Granth Sahib is recited, sung and revered in gurdwaras (Sikh temples) around the world, where the Langar, the communal soup kitchen that offers free meals to all, symbolizing equality and selfless service, is also practiced.

Sikhism Today: A Legacy of Faith and Service Sikhism continues to be a powerful force in the lives of millions of people, particularly in the Punjab region, but also in significant communities in North America, Europe and elsewhere. Sikhs are known for their spirit of community service, compassion and advocacy for human rights. In modern times, Sikhs continue to face challenges, including discrimination and misunderstandings about their faith and identity. However, Sikhs’ commitment to social justice, equality and service remains unwavering, reflecting the timeless teachings of their Gurus. Sikhism offers the world a model of practical spirituality and social activism, advocating a way of life that unites spiritual devotion with the moral responsibility to fight injustice. Sikhism’s message of unity, courage and compassion continues to resonate, offering a beacon of hope in an often divided world. Sikhism, with its roots in a period of great religious upheaval, has transcended time as a vibrant faith that preaches equality, advocacy for justice and devotion to one God. As they face the challenges of the modern world, Sikhs remain true to the values of their Gurus, inspiring millions with their devotion, courage and commitment to the common good.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Amrita Pritam was a renowned Indian writer and poet, celebrated for her literary contributions in Punjabi and Hindi literature

Amrita Pritam -

Amrita Pritam was a renowned Indian writer and poet, celebrated for her literary contributions in Punjabi and Hindi literature. Here's an overview of her biography:

Early Life:

Amrita Pritam, born Amrita Kaur, was a renowned Indian writer and poet, celebrated for her contributions to Punjabi literature. Here are some details about her early life:

1. Birth: Amrita Pritam was born on August 31, 1919, in Gujranwala, which was then part of British India and is now in present-day Pakistan.

2. Family Background: She was born into a Sikh family. Her father, Kartar Singh Hitkari, was a schoolteacher and a poet, which perhaps instilled in her an early love for literature.

3. Education: Pritam received her early education at the Khalsa College for Women in Lahore. She showed a keen interest in poetry and literature from a young age.

4. Marriage and Early Writing Career: At the age of 16, Amrita Pritam married Pritam Singh, an editor of a Punjabi literary magazine. This marked the beginning of her association with the world of literature. Her early poetry was published under the pen name Amrita Pritam.

5. Early Works: Pritam's early works reflected the social and cultural milieu of her time. She wrote about the experiences of women, the partition of India in 1947, and the human condition with depth and sensitivity.

6. Recognition: Her talent was recognized early on, and she became one of the leading literary figures of her generation. She received numerous awards and honors throughout her career, including the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1956 for her long poem "Sunehade" (Messages).

7.��Activism: Apart from her literary pursuits, Amrita Pritam was also known for her activism. She was deeply involved in social and political causes, advocating for the rights of women and marginalized communities.

Amrita Pritam's early life laid the foundation for her prolific literary career, which spanned several decades and left an indelible mark on Indian literature. Her works continue to inspire readers and writers alike with their timeless relevance and universal themes.

Literary Career:

Amrita Pritam began writing at a young age and gained recognition for her poetry during her teenage years. Her early works reflected themes of romanticism and rebellion against societal norms. She wrote extensively in Punjabi and later translated many of her works into Hindi and other languages.

Her most famous work is the Punjabi poem collection titled "Sunehade" (Messages), which was published in 1949. This collection earned her widespread acclaim and established her as a prominent voice in Punjabi literature.

Amrita Pritam's literary career spanned several decades and encompassed various forms of writing, including poetry, fiction, essays, and autobiographical works. Here are some details about her literary career:

1. Poetry:

Amrita Pritam is perhaps best known for her poetry, which she began writing at a young age. Her poetry reflects a deep sensitivity to human emotions, especially the experiences of women, love, and the socio-political realities of her time. Her poetic style is characterized by simplicity, sincerity, and emotional depth. Some of her notable poetry collections include "Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu" (Today I Invoke Waris Shah), "Kagaz Te Canvas" (Paper and Canvas), and "Naginaa Da Ishaq" (The Love of the Gem).

Amrita Pritam penned numerous poems throughout her prolific career, many of which have become celebrated for their emotional depth, social commentary, and lyrical beauty. Here are some of her most famous poems:

1. Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu (Today I Invoke Waris Shah): This poem, written in the aftermath of the partition of India in 1947, is perhaps one of Amrita Pritam's most renowned works. It addresses the Sufi poet Waris Shah, imploring him to rise from his grave and witness the devastation caused by the partition. It captures the anguish, pain, and longing for peace in the aftermath of communal violence.

2. Main Tenu Phir Milangi (I Will Meet You Again): This poem is a poignant expression of love and longing. It reflects on the enduring nature of love and the belief that despite physical separation, souls remain connected. It's often considered one of Pritam's most powerful and evocative love poems.

3. Aj Di Raat (Tonight): In this poem, Amrita Pritam explores themes of loneliness, existentialism, and the passage of time. The poem's speaker reflects on the solitude of the night and contemplates the mysteries of life and death.

4. Kagaz Te Canvas (Paper and Canvas): This collection of poems delves into various facets of life, love, and creativity. Pritam's verses in this collection are characterized by their simplicity, yet they carry profound philosophical insights and reflections on the human experience.

5. Naginaa Da Ishaq (The Love of the Gem): In this poem, Pritam employs imagery of precious gems to symbolize love and longing. The poem explores the depth of human emotions and the transformative power of love.

These are just a few examples of Amrita Pritam's famous poetry. Her body of work is vast and diverse, encompassing a wide range of themes and emotions. Pritam's poetry continues to resonate with readers for its timeless relevance and universal appeal.

2. Fiction: Alongside her poetry, Pritam also wrote fiction, including novels and short stories. Her fictional works often explore the complexities of human relationships, societal norms, and the struggles of women in patriarchal societies. One of her most famous novels is "Pinjar" (The Skeleton), which portrays the trauma and upheaval caused by the partition of India in 1947.

3. Autobiographical Works: Pritam wrote several autobiographical works, offering insights into her own life and experiences. "Rasidi Ticket" (Revenue Stamp) is one such notable autobiography where she candidly reflects on her life, love, and literary journey. Her autobiographical writings provide a glimpse into the cultural and historical context of her time.

4. Essays and Journalism: Pritam was also an accomplished essayist and journalist. She wrote extensively on various social, cultural, and political issues, advocating for gender equality, social justice, and peace. Her essays are marked by their intellectual rigor, clarity of thought, and commitment to progressive ideals.

5. Recognition and Awards: Amrita Pritam received numerous awards and honors for her literary contributions. She was the first woman to receive the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1956 for her long poem "Sunehade" (Messages). She was also honored with the Padma Vibhushan, one of India's highest civilian awards, in 2004, in recognition of her outstanding contribution to literature and social activism.

Amrita Pritam's literary legacy continues to inspire readers and writers around the world. Her works remain relevant for their exploration of universal themes and their profound insights into the human condition.

Amrita Pritam's love story-

Amrita Pritam's writing often explored themes such as love, loss, feminism, and the partition of India in 1947. She witnessed the horrors of the partition firsthand, an experience that deeply influenced her work. Her poignant prose and poetry captured the human suffering and emotional turmoil caused by the partition.

Notable Works:

Some of Amrita Pritam's notable works include:

- "Pinjar" (The Skeleton) - A novel that depicts the impact of partition on individuals and families.

- "Rasidi Ticket" (Revenue Stamp) - An autobiographical novel that delves into her personal life and relationships.

- "Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu" (Today I Invoke Waris Shah) - A poem lamenting the tragedies of partition and calling out to the 18th-century Punjabi Sufi poet Waris Shah.

- "Nanak Naam Jahaz Hai" (Nanak, the Boat of Name) - A novel exploring the life and teachings of Guru Nanak Dev, the founder of Sikhism.

Amrita Pritam's love story is one of the most famous and intriguing aspects of her life. Her relationship with the renowned poet Sahir Ludhianvi is often discussed in literary circles. Here's an overview of their love story:

Meeting and Relationship:

Amrita Pritam and Sahir Ludhianvi first met in 1944 when they were both young and aspiring poets in Lahore, which was then part of undivided India. Their meeting sparked a deep emotional connection, fueled by their shared passion for literature and poetry.

Their relationship blossomed against the backdrop of political turmoil and societal norms of the time. Both Amrita and Sahir were known for their progressive views and rebellious spirits, which further cemented their bond.

Challenges and Obstacles:

Despite their profound love for each other, Amrita and Sahir faced numerous challenges in their relationship. Sahir was known for his aloof and reserved nature, while Amrita was more expressive and emotive. Their differing personalities sometimes led to conflicts and misunderstandings.

Moreover, societal norms and personal circumstances posed significant obstacles to their love story. Sahir's commitment issues and reluctance to settle down in a conventional relationship added strain to their bond. Additionally, Amrita was already married to Pritam Singh, a prominent editor and writer, which further complicated their situation.

Literary Collaboration:

Despite the complexities of their personal relationship, Amrita Pritam and Sahir Ludhianvi continued to share a deep intellectual and artistic connection. They often exchanged letters and poems, exploring themes of love, longing, and separation in their writings.

Their literary collaboration produced some of their most renowned works, showcasing the depth of their emotional bond and creative synergy. Although their romantic relationship faced challenges, their artistic partnership endured, leaving a lasting impact on Indian literature.

Legacy:

Amrita Pritam's literary contributions have had a profound impact on Indian literature, particularly in the realms of poetry and fiction. She received numerous awards and honors throughout her career, including the Sahitya Akademi Award, the Padma Shri, and the Padma Vibhushan, among others.

Amrita Pritam passed away on October 31, 2005, leaving behind a rich legacy of literature that continues to inspire readers and writers alike. Her works remain relevant for their exploration of timeless themes and their powerful portrayal of the human experience.

0 notes

Text

The history of the Sikh is a rich palette of spiritual evolution, brave warriors and unshakable principles that have left an indelible mark on the world. The roots of Sikhism date back to the 15th century in the South Asian state of Punjab, where Guru Nanak Dev Ji, the first of the Sikh gurus, laid the foundation for a new faith based on the concept of the One Supreme Creator. Guru Nanak Dev Ji was a visionary mystic and philosopher who tried to bridge the gap between different religious and social communities. He advocated equality of all human beings irrespective of caste, religion and gender. Guru Nanak's teachings were captured in hymns and poems, which later became the holy scripture of Sikhism, known as the Guru Granth Sahib.

The family of Sikh Gurus continued even after Guru Nanak Dev ji passed away, each offering chadar to the other. After him Guru Angad Dev Ji, Guru Amar Das Ji, Guru Ram Das Ji and Guru Arjan Dev Ji became. Guru Arjan Dev ji played an important role in shaping Sikhism by compiling the writings of not only Sikh Gurus but also saints of different religions. This collection has become the basis of Sikh literature and has become an important guide for the Sikh community.

The fifth Guru, Guru Arjan Dev Ji, faced great persecution from the Mughal emperor Jahangir, who saw Sikhism as a challenge to his rule. Guru Arjan Dev Ji was martyred in 1606, becoming the first Sikh Guru to sacrifice his life for the principles he espoused.

Guru Hargobind Sahib, the sixth Guru, succeeded Guru Arjan Dev Ji and became the first teacher of the Guru Warriors. He led the Sikhs through a period of intense struggle against the oppressive Mughal rule. Guru Hargobind Sahib supported the Miri-Piri concept which emphasized spiritual and temporal authority. He wields two swords to symbolize this duality, marking the beginning of the Sikh martial tradition.

Guru Har Rai Ji and Guru Har Krishan Ji followed him as the seventh and eighth gurus respectively, contributing to the spiritual and humanitarian aspects of Sikhism. Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, the ninth Guru, stood out as a champion of religious freedom and tolerance. He sacrificed his life to protect the rights of Hindus and their religion during the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb.

Finally, the stage was set before the tenth and last human guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji. He faced enormous challenges in his life, including the loss of his father, Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, and the persecution of the Sikhs. Guru Gobind Singh Ji tried to awaken the Sikh community and prepare it to face difficulties with courage. In 1699 he founded the Khalsa, a special community of Sikhs bound by a code of conduct, baptized in Amri, the sacred nectar.

Under the leadership of Guru Gobind Singh Ji, the Sikhs became fearsome warriors and staunch defenders of the truth. The Khalsa formation instilled a spirit of fearlessness and devotion to justice among the Sikhs, empowering them to confront tyranny and oppression.

In the following centuries, the Sikh community suffered various trials and tribulations, but the principles of equality, service and devotion to the Creator remained unchanged. Sikh warriors such as Banda Singh Bahadur fought valiantly against tyranny and established a brief but influential Sikh kingdom in the early 18th century. After Baba Banda Singh Bahadur Martyrdom, there were many warriors: like Sardar Nawab Kapur, Sardar Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, Sardar Jassa Singh Ahluwaia, Sardar Hari Singh Nalwa and many more.

Sikh history embodies a legacy of spiritual enlightenment, unflinching courage and service to humanity. Today, Sikhs around the world continue to follow the teachings of their Gurus and contribute positively to their communities while maintaining the values that have defined their remarkable journey through history.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

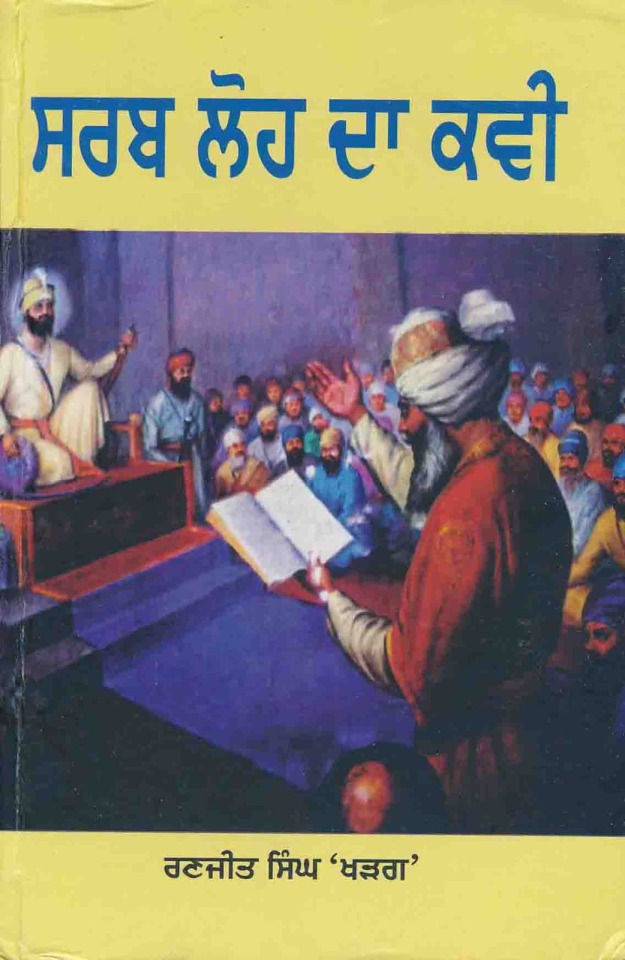

Sarabloh Da Kavi – Ranjit Singh Kharag

#Bachitar Natak#Chandi di Vaar#Dasam Granth#Fatehnama#Guru Gobind Singh Study Circle#Khalsa Advocate#Ranjit Singh Kharag#Sarabloh Da Kavi#Sikh Digital Library (SDL)

0 notes

Text

Real Talk: Providing Effective Aid

To help better, we need to understand better, especially as a creative social enterprise.

In the past few months, the Nest (the creative team behind Project Phoenix) and I have cold-emailed, and even slid into the DM’s of anybody who was willing to share their experience with the fires. And then we got it— 2 survivors, 2 volunteers and 2 solution providers. Each with stories worth sharing and hope worth highlighting through our Instagram series, Red Hue.

But, beyond these powerful stories, we wanted to draw out the bigger picture. There is a need for effective aid, and as a team, we’ve learnt so much about how to support our cause, simply by listening to our six interviewees. So we thought we’d share it with you.

Here’s what we’ve learned:

With the news coverage surrounding the devastation of the wildfires, it's so easy to overlook the different experiences of each survivor, and jump into conclusions instead. Stop. The last thing you want to do is to act on your own assumptions instead of solving the problem.

Check yourself before you wreck yourself. If your goal is to truly help and not do more harm than good, then do it well. Do your due diligence and take the time to understand what is truly needed.

So, get out there! Whether that’s by talking to those directly or indirectly affected by the fires, volunteering in evacuation shelters, or doing research on fire impact, be patient and learn as much as you can before taking action.

When the Nest and I sought out to learn more about how to help, through our Red Hue Series, we found two main topics that kept popping up with every story-- psychological and economic need.

Psychologically, remember that different people react to traumatic events differently. There is no one size fits all approach. In Red Hue, while Trevor needed a Nintendo DS to help him cope, Cheryl needed professional guidance as she processes her experience. As the American Psychological Association states, although “shock and denial are typical responses to large-scale natural disasters… there is no standard pattern of reaction.”

So what can we do to help? As Tracy, a licensed marriage and family therapist specializing in PTSD and trauma, sees it, “the best thing we can do sometimes is to just offer to sit with the person in silence, allowing them to reveal as much as they want to reveal. Just being in company with them works wonders, to let them know that we are simply here for them without wanting to ‘heal’ them or give advice.”

But let’s be real, the fires affect more than just the individuals. Economically, a wildfire could change the usage of state budgets, the economy of infrastructure, natural areas, and businesses, and the overall community. These are the external forces that take a toll on the community in the long run, beyond the psychological impact.

Past the hefty price tag of post-disaster recovery, if we-- as creative social enterprises-- aren’t aware of how “future benefits are only possible if the fire stimulates, rather than stops, economic development efforts associated with recovery and forest restoration,” then we wouldn’t be solving the issue effectively.

There’s no questioning the need for psychological and economic aid. But because the impact of the fires are both broad and situational, doing your research will help provide more context when assessing your cause, and finding the right solutions.

At Project Phoenix, we’re advocates of the Arthur Robert Ashe, Jr.’s ��Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.” So with all your research and knowledge, it’s time make things happen. Look at what you have, and assess the problem you’ve narrowed down on, with it.

The Sonoma Ash Project started out in Gregory’s garage as ash fell on his roof. He thought about what he could do with the material falling on his roof and “what followed was the idea of the gift of a ceramic piece, integrated with ashes collected from the ruins of people’s homes.” Gregory took his skills in pottery to create healing ceramic works, each marking a season of a survivor’s life. He started where he was, used what he had and did what he can.

Maybe you’ve already found the pottery to your Gregory, and want to know what other tools are available to push your project forward. So here’s what we’ve found in our experience-- much of providing effective aid relies on having knowledge in fundraising and utilizing data.

In most disaster-relief fundraisers, the number of donors tend to dwindle down as more time has passed from the event. People forget, they move on to the next big thing. But when you’re working for a cause, that can be a big hurdle. So keep your donors engaged by:

1. Showing them that their actions matter

2. Fostering a deeper senses of involvement within the fundraising process

3. Understanding their motivations on giving

While understanding your donor’s motivation of giving helps tailor your message, keep an open conversation on how your partnership is helping others, and don’t be afraid to take them in on the process. They want to help as much as you do, so don’t be shy with your progress.

While keeping your donors engaged is one thing, maximizing it is another. Chances are you already have your cause (the why) and your solution (the what and how). But when it comes to maximizing, it takes data to equip you with information on how much is needed, when and where.

Gurmun, a member of UC Davis’ Sikh Cultural Association (and yes, one of our interviewees), used his social media to gain traction for the club’s donation initiative. But to make sure they’re maximizing their resources, they utilized data made available by their partnership with Khalsa Aid.

And while partnerships are important, there are also alternatives-- Facebook’s Data for Good program being one of them. During the Thomas Fire, Facebook helped Direct Relief, as they were finding the right place to send out N-95 masks. From evacuation patterns, to how many people were in areas of heightened repository risks, Facebook’s free data equipped them with the how much, when and where, to ultimately, provide effective aid.

Beyond all the tools and tips we’ve jotted down, it’s important to remember that these are merely tools. They’re meant to help your cause, but they don’t make it what it is.

If there’s one takeaway worth remembering, it’s to trust in the process. The truth is, starting a project that helps others is a challenge. It’s one that pushes you out of your comfort zone and challenges you to stretch your resources. Trust us, we know. These things keep us up at night, too. But push through.

Even if you don’t see it right now, it’ll be worth all the late nights you spent researching, all the sleep missed, and all the anxiety fought. Take it from Chelsea, co-founder of Rebuild Wine Country, “don’t doubt yourself or your ability to make an impact.” Keep your head up, don’t forget why you started, and stay faithful in the process.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/yoga-mentorship-studentship-how-it-can-help-your-practice/

Yoga Mentorship + Studentship: How it Can Help Your Practice

Looking for a yoga mentorship? Here’s how to find the right yoga mentor, and be a good mentee, according to yoga teachers Elena Brower and Amy Ippoliti.

courtesy Elena Brower and Amy Ippoliti

Elena Brower and Amy Ippoliti first met when they were young yoga students studying to become teachers themselves. Now, they’re leading and mentoring the next generation of students and teachers. We caught up with the yoginis as they sat in Brower’s New York City living room to talk about lineage, mentorship, and what they agree is the key to strong leadership: studentship.

Elena Brower answers her mobile phone excitedly when I call. Sure, the busy New York City–based yoga teacher, life coach, and businesswoman is eager to talk about topics she’s passionate about—leadership, mentorship, and studentship—but she seems downright thrilled to announce on speakerphone that her dear friend, Amy Ippoliti, a Boulder, Colorado–based yoga teacher, is sitting right next to her.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

See also A Yoga Sequence for Insight with Elena Brower

Brower and Ippoliti go back 20 years, when they met as students of Cyndi Lee. Both would go on to study with John Friend, the founder of Anusara Yoga whose school crumbled in 2012 after allegations of unethical and illegal behavior. (They each turned in their Anusara certifications soon thereafter.) The pair leaned on each other after publicly denouncing their teacher’s behavior and as they figured out how to keep their lineage in mind while they struck out on their own.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

“I saw it as an opportunity for all of us to go and do what it is that we were always meant to be doing,” says Brower, “which was to teach the finest of what we’d been taught and to lead by example. Even though we couldn’t go forward in the paradigm we had known at that point, I think we paved new paths for ourselves, elegantly. Each of us took what resonated with us about the [Anusara] methodology and the heart space in which we were held for a long time, and we walked forward with it.”

“It’s true,” adds Ippoliti. “We evolved the teachings by bringing what was valuable and infusing our own individual work.”

“My hope is that [the next batch of teachers] have the courage to bring meaning to their yoga classes,” says Ippoliti.

courtesy Elena Brower and Amy Ippoliti

The Art of Studentship

One thing was clear to each of these yogis as they grew as teachers themselves: They were always going to remain students. “If I’m not continuously a student, I have nothing to offer as I’m teaching,” says Brower. “Studentship is an inherent part of being an effective teacher. It’s the backbone of what I do.”

The beauty of always being a student is that it is an ever-evolving practice—one that’s in stark contrast to the instant gratification to which we’ve grown accustomed these days, says Ippoliti. “What I find interesting about many of today’s yoga students is that there’s this perception that you can get all the info you need with Google or that you can become a public figure or yoga teacher simply by putting together an Instagram account and proclaiming you’re an expert,” she says. “But to me, studentship is a deep marinating and immersion into learning, where you are under the wings of a mentor or teacher. That kind of devotion and dedication, over time, is what you need to be a great teacher.”

See also Amy Ippoliti on Finding Happiness Through Seva

Ippoliti and Brower say it feels as if they’ve been in an academic pursuit of sorts over the years, studying under a host of teachers and mentors. Ippoliti talks about working with religion scholar Douglas Brooks and, more recently, connecting with Judith Hanson Lasater—two mentorships, among others, which have influenced her own yoga school, 90 Monkeys, and continue to shape her teaching and personal practice.

Brower says her main yoga mentor, Rod Stryker, and Kundalini Yoga teacher Hari Kaur Khalsa are “extremely skillful, personally and professionally, and have generously shared their wisdom” with her over the years. She also mentions a number of colleagues at doTERRA, an essential-oil marketing brand she works with, who’ve helped her ultimately lead a team of global wellness advocates.

“You’ve got to get under a mama bird,” says Ippoliti. “It is the way to hold a lineage in mind as you become a leader.”

The way to be a leader is clear, says Brower, and it’s intricately associated with your willingness to be a student.

courtesy Elena Brower and Amy Ippoliti

How to find a yoga mentor

So, you’ve found your mama bird—a teacher or mentor from whom you want to learn. Where do you go from there?

You simply stay close, says Ippoliti. “Not in a creepy way,” she says, chuckling. “But in a way that conveys that you’re just going to be around, learning.”

“You know what’s cool?” adds Brower. “There are a few people in my life who’ve done that—they’ve hung around—and those people have become accomplished teachers. Their studentship has helped them advance their own work and teaching.”

See also 10 Best Yoga and Meditation Books, According to 10 Top Yoga and Meditation Teachers

Brower adds that setting up a clear agreement between a mentor and mentee can be especially helpful. “When you’re asking someone if she’ll be a mentor to you, it’s critical to value her time,” she says. And whatever you do, show the person you’d like to be your mentor that you’re willing to do the work. “Very often, people ask if I will be their mentor, and I say, ‘OK, watch this video first or do this reading,’ and then many don’t come back to me,” she says. “If you’d like to be mentored, you have to make a commitment. And if you’re not willing to put in study time, I’m less likely to devote my own. That said, if you do make the commitment and dedicate yourself to your own learning, I’m happy to gently provide guidance.”

Brower says watching and helping other women grow their sense of what’s possible has been one of the greatest privileges of being a mentor. Ippoliti chimes in with eager agreement: “To me, it’s the most fulfilling thing in the world when a student comes forward and says, ‘I’m serious. I want to learn from you.’ Because when I know that student is serious, I also know she will ultimately help others at a level that is far more profound.”

The two friends, now in their 40s, start talking about their biggest hopes for the next batch of teachers—the 20-somethings who will become the next leaders of our community. “My hope is that they have the courage to bring meaning to their yoga classes,” says Ippoliti. “Sure, you can teach a class that helps students simply go through the motions, telling them to inhale and do this; exhale, do that. But yoga is more than that. It’s a practice, not an activity. It’s a means of inspiring people’s lives off the mat, and to ultimately help people feel better about themselves. I hope our next generation of teachers doesn’t gloss over all of that—that they have the courage to make the practice meaningful.”

See also How to Talk About Tough Stuff in Your Yoga Classes

The way to be a leader is clear, says Brower, and it’s intricately associated with your willingness to be a student. “The best leaders are the most humble and the most willing to learn and be corrected and guided,” she says. “So, sit yourself at the feet of your own teachers, even if they’re not physically there. Sit there in energy and in heart. Sit there daily, and in a way, serve them, too. If you do all of this, abundance will flow.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function() n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments) ;if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n; n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0';n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script','https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); (function() fbq('init', '1397247997268188'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); var contentId = 'ci023ac2937000262e'; if (contentId !== '') fbq('track', 'ViewContent', content_ids: [contentId], content_type: 'product'); )();

Source link

#Namaste Blog#teach#Tools for Teachers#yoga basics#yoga exercises#Yoga Teacher Training#Yoga Teachers#Yoga Exercises

0 notes

Text

ਰਿਮਾਂਡ ਖਤਮ ਹੋਣ 'ਤੇ ਜਗਤਾਰ ਸਿੰਘ, ਹਰਮਿੰਦਰ ਸਿੰਘ ਮਿੰਟੂ, ਧਰਮਿੰਦਰ ਸਿੰਘ ਗੁਗਨੀ ਨੂੰ ਭੇਜਿਆ ਜੇਲ੍ਹ

ਪੂਰੀ ਖਬਰ/ਲਿਖਤ ਪੜ੍ਹੋ: @ http://bit.ly/2jySpM8

ਸਕੌਟਲੈਂਡ / ਇੰਗਲੈਂਡ ਦੇ ਨਾਗਰਿਕ ਜਗਤਾਰ ਸਿੰਘ ਜੌਹਲ ਉਰਫ ਜੱਗੀ ਨੂੰ ਅੱ�� (17 ਨਵੰਬਰ, 2017) ਬਾਘਾਪੁਰਾਣਾ ਅਦਾਲਤ ‘ਚ ਪੇਸ਼ ਕੀਤਾ ਗਿਆ। ਜਿਥੇ ਰਿਮਾਂਡ ਖਤਮ ਹੋਣ ‘ਤੇ ਉਸਨੂੰ 14 ਦਿਨਾਂ ਦੀ ਨਿਆਂਇਕ ਹਿਰਾਸਤ ‘ਚ ਜੇਲ੍ਹ ਭੇਜ ਦਿੱਤਾ ਗਿਆ। ਉਹ ਪਿਛਲੇ 13 ਦਿਨਾਂ ਤੋਂ ਪੁਲਿਸ ਰਿਮਾਂਡ ‘ਤੇ ਸੀ, ਉਸਨੂੰ ਮੋਗਾ ਪੁਲਿਸ ਨੇ 4 ਨਵੰਬਰ ਨੂੰ ਉਸ ਵੇਲੇ ਚੁੱਕਿਆ ਸੀ ਜਦੋਂ ਉਹ ਆਪਣੀ ਪਤਨੀ ਅਤੇ ਭੈਣ ਨਾਲ ਜਲੰਧਰ ਦੇ ਰਾਮਾ ਮੰਡੀ ਇਲਾਕੇ ‘ਚ ਸੀ।

ਪੂਰੀ ਖਬਰ/ਲਿਖਤ ਪੜ੍ਹੋ: @ http://www.sikhsiyasat.info/2017/11/uk-citizen-jagtar-singh-johal-jaggi-sent-to-jail-under-judicial-custody-till-nov-30/

#Bhai Harpal Singh Cheema#Dal Khalsa#Harminder Singh Mintoo#Jagtar Singh Johal alias Jaggi (UK)#Jaspal Singh Manjhpur (Advocate)#Punjab Police#Punjab Politics#Sikh Diaspora#Sikh News UK#Sikh Political Prisoners#Sikhs in United Kingdom

0 notes

Text

Battle of Balakot (1831): Foremost Wahabi Jihad crushed by Brave Sikhs

Battle of Balakot The battle of Balakot was fought between Sikhs under the leadership of Sher-e-Punjab Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Mujahedeen under the supervision of the Barelvi and Dehlavi families. Barelvis under Syed Ahmad Barelvi along with his associate Dehlvis under Shah Ismail Dehlvi clashed with Khalsa Army on 6th May 1831. Syed Ahmad Barelvi of Rai Bareilly was influenced by the teachings of (Abdul Wahab of Saudi Arabia) and (Shag Waliullah of Delhi). They condemned the western influence on Islam and advocated a return to Pure Islam. The important teaching center was at Patna. They started Wahabi Movement and came to Kashmir to instigate people to fight against Sikhs (because at that time, Kashmir was under the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and was a province of Khalsa Raj aka Sikh Empire). Barelvi and Dehlvi wanted to re-establish Muslim rule in Kashmir. Barelvi and his Mujahedeen army fought small skirmishes with the Sikhs but lost again and again. In 1831, Maharaja Ranjit Singh came to know that both (Barelvi And Dehlvi) were hiding at Balakot and had started terror camps in Balakot giving training to Mujahidin to fight against Sikh Empire. This time he sent General Hari Singh Nalwa (nicknamed the Tiger-Killer) to Balakot to completely uproot and kill the Mujahedeen army. On 6th May 1831 the battle was fought at Balakot in which thousands of Mujahedeen army men were killed and their leaders Dehlvi And Barelvi were also beheaded. Sikh army completely destroyed their terror training camps. Read More Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sasrikal Aroraji

I met him on Bandra Hill Road liked his look , his turban , his peaceful attitude and shot a few frames.

He belongs to the Sikh religion.

about Sikhism

Sikhism,[1] founded in fifteenth century Punjab on the teachings of Guru Nanak Dev and ten successive Sikh Gurus (the last one being the sacred text Guru Granth Sahib), is the fifth-largest organized religion in the world.[2] This system of religious philosophy and expression has been traditionally known as the Gurmat (literally the counsel of the gurus) or the Sikh Dharma. Sikhism originated from the word Sikh, which in turn comes from the Sanskrit root śiṣya meaning "disciple" or "learner", or śikṣa meaning "instruction".[3][4]

The principal belief of Sikhism is faith in waheguru—represented using the sacred symbol of ik ōaṅkār, the Universal God. Sikhism advocates the pursuit of salvation through disciplined, personal meditation on the name and message of God. A key distinctive feature of Sikhism is a non-anthropomorphic concept of God, to the extent that one can interpret God as the Universe itself. The followers of Sikhism are ordained to follow the teachings of the ten Sikh gurus, or enlightened leaders, as well as the holy scripture entitled the Gurū Granth Sāhib, which, along with the writings of six of the ten Sikh Gurus, includes selected works of many devotees from diverse socio-economic and religious backgrounds. The text was decreed by Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth guru, as the final guru of the Khalsa Panth. Sikhism’s traditions and teachings are distinctively associated with the history, society and culture of the Punjab. Adherents of Sikhism are known as Sikhs (students or disciples) and number over 23 million across the world. Most Sikhs live in Punjab in India and, until India’s partition, millions of Sikhs lived in what is now Pakistani Punjab.[5]

The origins of Sikhism lie in the teachings of Guru Nanak and his successors. The essence of Sikh teaching is summed up by Nanak in these words: "Realisation of Truth is higher than all else. Higher still is truthful living".[6] Sikhism believes in equality of all humans and rejects discrimination on the basis of caste, creed, and gender. Sikhism also does not attach any importance to asceticism as a means to attain salvation, but stresses on the need of leading life as a householder.

Sikhism is a monotheistic religion.[7][8] In Sikhism, God—termed Vāhigurū—is shapeless, timeless, and sightless: niraṅkār, akāl, and alakh. The beginning of the first composition of Sikh scripture is the figure "1"—signifying the universality of God. It states that God is omnipresent and infinite, and is signified by the term ēk ōaṅkār.[9] Sikhs believe that before creation, all that existed was God and Its hukam (will or order).[10] When God willed, the entire cosmos was created. From these beginnings, God nurtured "enticement and attachment" to māyā, or the human perception of reality.[11]

While a full understanding of God is beyond human beings,[9] Nanak described God as not wholly unknowable. God is omnipresent (sarav viāpak) in all creation and visible everywhere to the spiritually awakened. Nanak stressed that God must be seen from "the inward eye", or the "heart", of a human being: devotees must meditate to progress towards enlightenment. Guru Nanak Dev emphasized the revelation through meditation, as its rigorous application permits the existence of communication between God and human beings.[9] God has no gender in Sikhism, (though translations may incorrectly present a male God); indeed Sikhism teaches that God is "Nirankar" [Niran meaning "without" and kar meaning "form", hence "without form"]. In addition, Nanak wrote that there are many worlds on which God has created life.[12] [edit] Pursuing salvation and khalsa A Sikh man at the Harimandir Sahib

Nanak’s teachings are founded not on a final destination of heaven or hell, but on a spiritual union with God which results in salvation.[13] The chief obstacles to the attainment of salvation are social conflicts and an attachment to worldly pursuits, which commit men and women to an endless cycle of birth—a concept known as reincarnation.

Māyā—defined as illusion or "unreality"—is one of the core deviations from the pursuit of God and salvation: people are distracted from devotion by worldly attractions which give only illusive satisfaction. However, Nanak emphasised māyā as not a reference to the unreality of the world, but of its values. In Sikhism, the influences of ego, anger, greed, attachment, and lust—known as the Five Evils—are believed to be particularly pernicious. The fate of people vulnerable to the Five Evils is separation from God, and the situation may be remedied only after intensive and relentless devotion.[14]

Nanak described God’s revelation—the path to salvation—with terms such as nām (the divine Name) and śabad (the divine Word) to emphasise the totality of the revelation. Nanak designated the word guru (meaning teacher) as the voice of God and the source and guide for knowledge and salvation.[15] Salvation can be reached only through rigorous and disciplined devotion to God. Nanak distinctly emphasised the irrelevance of outward observations such as rites, pilgrimages, or asceticism. He stressed that devotion must take place through the heart, with the spirit and the soul.

A key practice to be pursued is nām: remembrance of the divine Name. The verbal repetition of the name of God or a sacred syllable is an established practice in religious traditions in India, but Nanak’s interpretation emphasized inward, personal observance. Nanak’s ideal is the total exposure of one’s being to the divine Name and a total conforming to Dharma or the "Divine Order". Nanak described the result of the disciplined application of nām simraṇ as a "growing towards and into God" through a gradual process of five stages. The last of these is sac khaṇ��� (The Realm of Truth)—the final union of the spirit with God.[15]

Nanak stressed now kirat karō: that a Sikh should balance work, worship, and charity, and should defend the rights of all creatures, and in particular, fellow human beings. They are encouraged to have a chaṛdī kalā, or optimistic, view of life. Sikh teachings also stress the concept of sharing—vaṇḍ chakkō—through the distribution of free food at Sikh gurdwaras (laṅgar), giving charitable donations, and working for the good of the community and others (sēvā). [edit] The ten gurus and religious authority Main article: Sikh Gurus A rare Tanjore-style painting from the late 19th century depicting the ten Sikh Gurus with Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana.

The term guru comes from the Sanskrit gurū, meaning teacher, guide, or mentor. The traditions and philosophy of Sikhism were established by ten specific gurus from 1499 to 1708. Each guru added to and reinforced the message taught by the previous, resulting in the creation of the Sikh religion. Nanak was the first guru and appointed a disciple as successor. Gobind Singh was the final guru in human form. Before his death, Gobind Singh decreed that the Gurū Granth Sāhib would be the final and perpetual guru of the Sikhs.[16] The Sikhs believe that the spirit of Nanak was passed from one guru to the next, " just as the light of one lamp, which lights another and does not diminish ",[17] and is also mentioned in their holy book.

After Nanak’s passing, the most important phase in the development of Sikhism came with the third successor, Amar Das. Nanak’s teachings emphasised the pursuit of salvation; Amar Das began building a cohesive community of followers with initiatives such as sanctioning distinctive ceremonies for birth, marriage, and death. Amar Das also established the manji (comparable to a diocese) system of clerical supervision.[15] The interior of the Akal Takht

Amar Das’s successor and son-in-law Ram Das founded the city of Amritsar, which is home of the Harimandir Sahib and regarded widely as the holiest city for all Sikhs. When Ram Das’s youngest son Arjan succeeded him, the line of male gurus from the Sodhi Khatri family was established: all succeeding gurus were direct descendants of this line. Arjun Mathur was responsible for compiling the Sikh scriptures. Guru Arjan Sahib was captured by Mughal authorities who were suspicious and hostile to the religious order he was developing.[18] His persecution and death inspired his successors to promote a military and political organization of Sikh communities to defend themselves against the attacks of Mughal forces.

The Sikh gurus established a mechanism which allowed the Sikh religion to react as a community to changing circumstances. The sixth guru, Har Gobind, was responsible for the creation of the concept of Akal Takht (throne of the timeless one), which serves as the supreme decision-making centre of Sikhdom and sits opposite the Darbar Sahib. The Sarbat Ḵẖālsā (a representative portion of the Khalsa Panth) historically gathers at the Akal Takht on special festivals such as Vaisakhi or Diwali and when there is a need to discuss matters that affect the entire Sikh nation. A gurmatā (literally, guru’s intention) is an order passed by the Sarbat Ḵẖālsā in the presence of the Gurū Granth Sāhib. A gurmatā may only be passed on a subject that affects the fundamental principles of Sikh religion; it is binding upon all Sikhs.[19] The term hukamnāmā (literally, edict or royal order) is often used interchangeably with the term gurmatā. However, a hukamnāmā formally refers to a hymn from the Gurū Granth Sāhib which is given as an order to Sikhs. [edit] History Main article: History of Sikhism

Nanak (1469–1538), the founder of Sikhism, was born in the village of Rāi Bhōi dī Talwandī, now called Nankana Sahib (in present-day Pakistan).[20] His father, Mehta Kalu was a Patwari, an accountant of land revenue in the employment of Rai Bular Bhatti, the area landlord. Nanak’s mother was Tripta Devi and he had one older sister, Nanaki. His parents were Khatri Hindus of the Bedi clan. As a boy, Nanak was fascinated by religion, and his desire to explore the mysteries of life eventually led him to leave home and take missionary journeys.

In his early teens, Nanak caught the attention of the local landlord Rai Bular Bhatti, who was moved by his intellect and divine qualities. Rai Bular was witness to many incidents in which Nanak enchanted him and as a result Rai Bular and Nanak’s sister Bibi Nanki, became the first persons to recognise the divine qualities in Nanak. Both of them then encouraged and supported Nanak to study and travel. Sikh tradition states that at the age of thirty, Nanak went missing and was presumed to have drowned after going for one of his morning baths to a local stream called the Kali Bein. One day, he declared: "There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim" (in Punjabi, "nā kōi hindū nā kōi musalmān"). It was from this moment that Nanak would begin to spread the teachings of what was then the beginning of Sikhism.[21] Although the exact account of his itinerary is disputed, he is widely acknowledged to have made four major journeys, spanning thousands of kilometres, the first tour being east towards Bengal and Assam, the second south towards Tamil Nadu, the third north towards Kashmir, Ladakh, and Tibet, and the final tour west towards Baghdad and Mecca.[22]

Nanak was married to Sulakhni, the daughter of Moolchand Chona, a rice trader from the town of Bakala. They had two sons. The elder son, Sri Chand, was an ascetic, and he came to have a considerable following of his own, known as the Udasis. The younger son, Lakshmi Das, on the other hand, was totally immersed in worldly life. To Nanak, who believed in the ideal of rāj maiṁ jōg (detachment in civic life), both his sons were unfit to carry on the Guruship. [edit] Growth of the Sikh community

In 1538, Nanak chose his disciple Lahiṇā, a Khatri of the Trehan clan, as a successor to the guruship rather than either of his sons. Lahiṇā was named Angad Dev and became the second guru of the Sikhs.[23] Nanak conferred his choice at the town of Kartarpur on the banks of the river Ravi, where Nanak had finally settled down after his travels. Though Sri Chand was not an ambitious man, the Udasis believed that the Guruship should have gone to him, since he was a man of pious habits in addition to being Nanak’s son. They refused to accept Angad’s succession. On Nanak’s advice, Angad shifted from Kartarpur to Khadur, where his wife Khivi and children were living, until he was able to bridge the divide between his followers and the Udasis. Angad continued the work started by Nanak and is widely credited for standardising the Gurmukhī script as used in the sacred scripture of the Sikhs.

Amar Das, a Khatri of the Bhalla clan, became the third Sikh guru in 1552 at the age of 73. Goindval became an important centre for Sikhism during the guruship of Amar Das. He preached the principle of equality for women by prohibiting purdah and sati. Amar Das also encouraged the practice of langar and made all those who visited him attend laṅgar before they could speak to him.[24] In 1567, Emperor Akbar sat with the ordinary and poor people of Punjab to have laṅgar. Amar Das also trained 146 apostles of which 52 were women, to manage the rapid expansion of the religion.[25] Before he died in 1574 aged 95, he appointed his son-in-law Jēṭhā, a Khatri of the Sodhi clan, as the fourth Sikh guru.

Jēṭhā became Ram Das and vigorously undertook his duties as the new guru. He is responsible for the establishment of the city of Ramdaspur later to be named Amritsar. Before Ramdaspur, Amritsar was known as Guru Da Chakk. In 1581, Arjan Dev—youngest son of the fourth guru—became the fifth guru of the Sikhs. In addition to being responsible for building the Darbar/Harimandir Sahib (called the Golden Temple), he prepared the Sikh sacred text known as the Ādi Granth (literally the first book) and included the writings of the first five gurus. In 1606, for refusing to make changes to the Granth and for supporting an unsuccessful contender to the throne, he was tortured and killed by the Mughal Emperor, Jahangir.[26] [edit] Political advancement

Hargobind, became the sixth guru of the Sikhs. He carried two swords—one for spiritual and the other for temporal reasons (known as mīrī and pīrī in Sikhism).[27] Sikhs grew as an organized community and under the 10th Guru the Sikhs developed a trained fighting force to defend their independence. In 1644, Har Rai became guru followed by Harkrishan, the boy guru, in 1661. No hymns composed by these three gurus are included in the Sikh holy book.[28]

Tegh Bahadur became guru in 1665 and led the Sikhs until 1675. Teg Bahadur was executed by Aurangzeb for helping to protect Hindus, after a delegation of Kashmiri Pandits came to him for help when the Emperor condemned them to death for failing to convert to Islam.[29] He was succeeded by his son, Gobind Rai who was just nine years old at the time of his father’s death. Gobind Rai further militarised his followers, and was baptised by the Pañj Piārē when he formed the Khalsa on 13 April 1699. From here on in he was known as Gobind Singh.

From the time of Nanak, when it was a loose collection of followers who focused entirely on the attainment of salvation and God, the Sikh community had significantly transformed. Even though the core Sikh religious philosophy was never affected, the followers now began to develop a political identity. Conflict with Mughal authorities escalated during the lifetime of Teg Bahadur and Gobind Singh. The latter founded the Khalsa in 1699. The Khalsa is a disciplined community that combines its religious purpose and goals with political and military duties.[30] After Aurangzeb killed four of his sons, Gobind Singh sent Aurangzeb the Zafarnamah (Notification/Epistle of Victory).

Shortly before his death, Gobind Singh ordered that the Gurū Granth Sāhib (the Sikh Holy Scripture), would be the ultimate spiritual authority for the Sikhs and temporal authority would be vested in the Khalsa Panth—the Sikh Nation/Community.[16] The first scripture was compiled and edited by the fifth guru, Arjan Dev, in 1604.

A former ascetic was charged by Gobind Singh with the duty of punishing those who had persecuted the Sikhs. After the guru’s death, Baba Banda Singh Bahadur became the leader of the Sikh army and was responsible for several attacks on the Mughal empire. He was executed by the emperor Jahandar Shah after refusing the offer of a pardon if he converted to Islam.[31]

The Sikh community’s embrace of military and political organisation made it a considerable regional force in medieval India and it continued to evolve after the demise of the gurus. After the death of Baba Banda Singh Bahadur, a Sikh Confederacy of Sikh warrior bands known as misls formed. With the decline of the Mughal empire, a Sikh Empire arose in the Punjab under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, with its capital in Lahore and limits reaching the Khyber Pass and the borders of China. The order, traditions and discipline developed over centuries culminated at the time of Ranjit Singh to give rise to the common religious and social identity that the term "Sikhism" describes.[32]

After the death of Ranjit Singh, the Sikh Empire fell into disorder and was eventually annexed by the United Kingdom after the hard-fought Anglo-Sikh Wars. This brought the Punjab under the British Raj. Sikhs formed the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee and the Shiromani Akali Dal to preserve Sikhs’ religious and political organization a quarter of a century later. With the partition of India in 1947, thousands of Sikhs were killed in violence and millions were forced to leave their ancestral homes in West Punjab.[33] Sikhs faced initial opposition from the Government in forming a linguistic state that other states in India were afforded. The Akali Dal started a non-violence movement for Sikh and Punjabi rights. Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale emerged as a leader of the Bhindran-Mehta Jatha—which assumed the name of Damdami Taksal in 1977 to promote a peaceful solution of the problem. In June 1984, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian army to launch Operation Blue Star to remove Bhindranwale and his followers from the Darbar Sahib. Bhindranwale, and a large number of innocent pilgrims were killed during the army’s operations. In October, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards. The assassination was followed by the 1984 Anti-Sikh riots massacre[34] and Hindu-Sikh conflicts in Punjab, as a reaction to the assassination and Operation Blue Star. [edit] Scripture

There are two primary sources of scripture for the Sikhs: the Gurū Granth Sāhib and the Dasam Granth. The Gurū Granth Sāhib may be referred to as the Ādi Granth—literally, The First Volume—and the two terms are often used synonymously. Here, however, the Ādi Granth refers to the version of the scripture created by Arjan Dev in 1604. The Gurū Granth Sāhib refers to the final version of the scripture created by Gobind Singh. [edit] Adi Granth Main article: Ādi Granth

The Ādi Granth was compiled primarily by Bhai Gurdas under the supervision of Arjan Dev between the years 1603 and 1604.[35] It is written in the Gurmukhī script, which is a descendant of the Laṇḍā script used in the Punjab at that time.[36] The Gurmukhī script was standardised by Angad Dev, the second guru of the Sikhs, for use in the Sikh scriptures and is thought to have been influenced by the Śāradā and Devanāgarī scripts. An authoritative scripture was created to protect the integrity of hymns and teachings of the Sikh gurus and selected bhagats. At the time, Arjan Sahib tried to prevent undue influence from the followers of Prithi Chand, the guru’s older brother and rival.[37]

The original version of the Ādi Granth is known as the kartārpur bīṛ and is claimed to be held by the Sodhi family of Kartarpur.[citation needed] (In fact the original volume was burned by Ahmad Shah Durrani’s army in 1757 when they burned the whole town of Kartarpur.)[citation needed] [edit] Guru Granth Sahib Gurū Granth Sāhib folio with Mūl Mantra Main article: Gurū Granth Sāhib

The final version of the Gurū Granth Sāhib was compiled by Gobind Singh in 1678. It consists of the original Ādi Granth with the addition of Teg Bahadur’s hymns. It was decreed by Gobind Singh that the Granth was to be considered the eternal guru of all Sikhs; however, this tradition is not mentioned either in ‘Guru Granth Sahib’ or in ‘Dasam Granth’.

Punjabi: ਸੱਬ ਸਿੱਖਣ ਕੋ ਹੁਕਮ ਹੈ ਗੁਰੂ ਮਾਨਯੋ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ । Transliteration: Sabb sikkhaṇ kō hukam hai gurū mānyō granth. English: All Sikhs are commanded to take the Granth as Guru.

It contains compositions by the first five gurus, Teg Bahadur and just one śalōk (couplet) from Gobind Singh.[38] It also contains the traditions and teachings of sants (saints) such as Kabir, Namdev, Ravidas, and Sheikh Farid along with several others.[32]

The bulk of the scripture is classified into rāgs, with each rāg subdivided according to length and author. There are 31 main rāgs within the Gurū Granth Sāhib. In addition to the rāgs, there are clear references to the folk music of Punjab. The main language used in the scripture is known as Sant Bhāṣā, a language related to both Punjabi and Hindi and used extensively across medieval northern India by proponents of popular devotional religion.[30] The text further comprises over 5000 śabads, or hymns, which are poetically constructed and set to classical form of music rendition, can be set to predetermined musical tāl, or rhythmic beats. A group of Sikh musicians at the Golden Temple complex

The Granth begins with the Mūl Mantra, an iconic verse created by Nanak:

Punjabi: ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥ ISO 15919 transliteration: Ika ōaṅkāra sati nāmu karatā purakhu nirabha’u niravairu akāla mūrati ajūnī saibhaṅ gura prasādi. Simplified transliteration: Ik ōaṅkār sat nām kartā purkh nirbha’u nirvair akāl mūrat ajūnī saibhaṅ gur prasād. English: One Universal Creator God, The Name Is Truth, Creative Being Personified, No Fear, No Hatred, Image Of The Timeless One, Beyond Birth, Self Existent, By Guru’s Grace.

All text within the Granth is known as gurbānī. Gurbānī, according to Nanak, was revealed by God directly, and the authors wrote it down for the followers. The status accorded to the scripture is defined by the evolving interpretation of the concept of gurū. In the Sant tradition of Nanak, the guru was literally the word of God. The Sikh community soon transferred the role to a line of men who gave authoritative and practical expression to religious teachings and traditions, in addition to taking socio-political leadership of Sikh adherents. Gobind Singh declared an end of the line of human gurus, and now the Gurū Granth Sāhib serves as the eternal guru, with its interpretation vested with the community.[30] [edit] Dasam Granth Main article: Dasam Granth A frontispiece to the Dasam Granth

The Dasam Granth (formally dasvēṁ pātśāh kī granth or The Book of the Tenth Master) is an eighteenth-century collection of poems by Gobind Singh. It was compiled in the shape of a book (granth) by Bhai Mani Singh some 13 to 26 years after Guru Gobind Singh Ji left this world for his heavenly abode.

From 1895 to 1897, different scholars and theologians assembled at the Akal Takht, Amritsar, to study the 32 printed Dasam Granths and prepare the authoritative version. They met at the Akal Takhat at Amritsar, and held formal discussions in a series of meetings between 13 June 1895 and 16 February 1896. A preliminary report entitled Report Sodhak (revision) Committee Dasam Patshah de Granth Sahib Di was sent to Sikh scholars and institutions, inviting their opinion. A second document, Report Dasam Granth di Sudhai Di was brought out on 11 February 1898. Basing its conclusions on a study of the old handwritten copies of the Dasam Granth preserved at Sri Takht Sahib at Patna and in other Sikh gurudwaras, this report affirmed that the Holy Volume was compiled at Anandpur Sahib in 1698[3] . Further re-examinations and reviews took place in 1931, under the aegis of the Darbar Sahib Committee of the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee. They, too, vindicated the earlier conclusion (agreeing that it was indeed the work of the Guru) and its findings have since been published. [edit] Janamsakhis Main article: Janamsākhīs

The Janamsākhīs (literally birth stories), are writings which profess to be biographies of Nanak. Although not scripture in the strictest sense, they provide an interesting look at Nanak’s life and the early start of Sikhism. There are several—often contradictory and sometimes unreliable—Janamsākhīs and they are not held in the same regard as other sources of scriptural knowledge. [edit] Observances

Observant Sikhs adhere to long-standing practices and traditions to strengthen and express their faith. The daily recitation from memory of specific passages from the Gurū Granth Sāhib, especially the Japu (or Japjī, literally chant) hymns is recommended immediately after rising and bathing. Family customs include both reading passages from the scripture and attending the gurdwara (also gurduārā, meaning the doorway to God; sometimes transliterated as gurudwara). There are many gurdwaras prominently constructed and maintained across India, as well as in almost every nation where Sikhs reside. Gurdwaras are open to all, regardless of religion, background, caste, or race.

Worship in a gurdwara consists chiefly of singing of passages from the scripture. Sikhs will commonly enter the temple, touch the ground before the holy scripture with their foreheads, and make an offering. The recitation of the eighteenth century ardās is also customary for attending Sikhs. The ardās recalls past sufferings and glories of the community, invoking divine grace for all humanity.[39]

The most sacred shrine is the Harimandir Sahib in Amritsar, famously known as the Golden Temple. Groups of Sikhs regularly visit and congregate at the Harimandir Sahib. On specific occasions, groups of Sikhs are permitted to undertake a pilgrimage to Sikh shrines in the province of Punjab in Pakistan, especially at Nankana Sahib and other Gurdwaras. Other places of interest to Sikhism in Pakistan includes the samādhī (place of cremation) of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Lahore. [edit] Sikh festivals

Festivals in Sikhism mostly centre around the lives of the Gurus and Sikh martyrs. The SGPC, the Sikh organisation in charge of upkeep of the gurdwaras, organises celebrations based on the new Nanakshahi calendar. This calendar is highly controversial among Sikhs and is not universally accepted. Several festivals (Hola Mohalla, Diwali, and Nanak’s birthday) continue to be celebrated using the Hindu calendar. Sikh festivals include the following:

* Gurpurabs are celebrations or commemorations based on the lives of the Sikh gurus. They tend to be either birthdays or celebrations of Sikh martyrdom. All ten Gurus have Gurpurabs on the Nanakshahi calendar, but it is Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Gobind Singh who have a gurpurab that is widely celebrated in Gurdwaras and Sikh homes. The martyrdoms are also known as a shaheedi Gurpurab, which mark the martyrdom anniversary of Guru Arjan Dev and Guru Tegh Bahadur. * Vaisakhi or Baisakhi normally occurs on 13 April and marks the beginning of the new spring year and the end of the harvest. Sikhs celebrate it because on Vaisakhi in 1699, the tenth guru, Gobind Singh, laid down the Foundation of the Khalsa an Independent Sikh Identity. * Bandi Chhor Divas or Diwali celebrates Hargobind’s release from the Gwalior Fort, with several innocent Hindu kings who were also imprisoned by Jahangir, on 26 October, 1619. * Hola Mohalla occurs the day after Holi and is when the Khalsa Panth gather at Anandpur and display their warrior skills, including fighting and riding.

[edit] Ceremonies and customs The anand kāraj (Sikh marriage) ceremony

Nanak taught that rituals, religious ceremonies, or idol worship is of little use and Sikhs are discouraged from fasting or going on pilgrimages.[40] However, during the period of the later gurus, and owing to increased institutionalisation of the religion, some ceremonies and rites did arise. Sikhism is not a proselytizing religion and most Sikhs do not make active attempts to gain converts. However, converts to Sikhism are welcomed, although there is no formal conversion ceremony. The morning and evening prayers take about two hours a day, starting in the very early morning hours. The first morning prayer is Guru Nanak’s Jap Ji. Jap, meaning "recitation", refers to the use of sound, as the best way of approaching the divine. Like combing hair, hearing and reciting the sacred word is used as a way to comb all negative thoughts out of the mind. The second morning prayer is Guru Gobind Singh’s universal Jaap Sahib. The Guru addresses God as having no form, no country, and no religion but as the seed of seeds, sun of suns, and the song of songs. The Jaap Sahib asserts that God is the cause of conflict as well as peace, and of destruction as well as creation. Devotees learn that there is nothing outside of God’s presence, nothing outside of God’s control. Devout Sikhs are encouraged to begin the day with private meditations on the name of God.

Upon a child’s birth, the Guru Granth Sāhib is opened at a random point and the child is named using the first letter on the top left-hand corner of the left page. All boys are given the middle name or surname Singh, and all girls are given the middle name or surname Kaur.[41] Sikhs are joined in wedlock through the anand kāraj ceremony. Sikhs are required to marry when they are of a sufficient age (child marriage is taboo), and without regard for the future spouse’s caste or descent. The marriage ceremony is performed in the company of the Guru Granth Sāhib; around which the couple circles four times. After the ceremony is complete, the husband and wife are considered "a single soul in two bodies."[42]

According to Sikh religious rites, neither husband nor wife is permitted to divorce. A Sikh couple that wishes to divorce may be able to do so in a civil court—but this is not condoned.[43] Upon death, the body of a Sikh is usually cremated. If this is not possible, any means of disposing the body may be employed. The kīrtan sōhilā and ardās prayers are performed during the funeral ceremony (known as antim sanskār).[44] [edit] Baptism and the Khalsa A kaṛā, kaṅghā and kirpān.

Khalsa (meaning pure) is the name given by Gobind Singh to all Sikhs who have been baptised or initiated by taking ammrit in a ceremony called ammrit sañcār. The first time that this ceremony took place was on Vaisakhi, which fell on 29 March 1698/1699 at Anandpur Sahib in Punjab. It was on that occasion that Gobind Singh baptised the Pañj Piārē who in turn baptised Gobind Singh himself.

Baptised Sikhs are bound to wear the Five Ks (in Punjabi known as pañj kakkē or pañj kakār), or articles of faith, at all times. The tenth guru, Gobind Singh, ordered these Five Ks to be worn so that a Sikh could actively use them to make a difference to their own and to others’ spirituality. The 5 items are: kēs (uncut hair), kaṅghā (small comb), kaṛā (circular iron bracelet), kirpān (dagger), and kacchā (special undergarment). The Five Ks have both practical and symbolic purposes.[45] [edit] Sikh people Main article: Sikh Further information: Sikhism by country Punjabi Sikh family from Punjab, India

Worldwide, there are 25.8 million Sikhs and approximately 75% of Sikhs live in the Indian state of Punjab, where they constitute about 60% of the state’s population. Even though there are a large number of Sikhs in the world, certain countries have not recognised Sikhism as a major religion and Sikhism has no relation to Hinduism. Large communities of Sikhs live in the neighboring states, and large communities of Sikhs can be found across India. However, Sikhs only make up about 2% of the Indian population.

In addition to social divisions, there is a misperception that there are a number of Sikh sectarian groups[clarification needed], such as Namdharis and Nirankaris. Nihangs tend to have little difference in practice and are considered the army of Sikhism. There is also a sect known as Udasi, founded by Sri Chand who were initially part of Sikhism but later developed into a monastic order.

Sikh Migration beginning from the 19th century led to the creation of significant communities in Canada (predominantly in Brampton, along with Malton in Ontario and Surrey in British Columbia), East Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, the United Kingdom and more recently, Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Western Europe. Smaller populations of Sikhs are found in Mauritius, Malaysia, Fiji, Nepal, China, Pakistan, Afganistan, Iraq and many other countries

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikhism.

Posted by firoze shakir photographerno1 on 2009-12-10 09:41:29

Tagged: , sikh , sikhism , aroraji , about sikhism

The post Sasrikal Aroraji appeared first on Good Info.

0 notes

Text

Sri Satguru Ram Singhji

About Sri Satguru Ram Singhji

He was born in 1816 in Ludhiana and was a great spiritual guru, a thinker, a seer, philosopher, social reformer, and a freedom fighter.

He fought against the caste system among Sikhs and encouraged inter-caste marriages.

He preached against killing the girl child in infancy, stood firmly against the Sati Pratha and advocated widow remarriage.

The movement was founded in 1840 by Bhagat Jawaharmal in Western Punjab.

Its basic tenets were abolition of caste and similar discriminations among Sikhs, discouraging the eating of meat and taking of alcohol and drugs, and encouraging women to step out of seclusion.

After the British took the Punjab, the movement transformed from a religious purification campaign to a political one.

During the Mutiny of 1857, Satguru Ram Singhji formally inaugurated the Namdhari movement, with a set of rituals modelled after Guru Gobind Singh’s founding of the Khalsa.

He strongly opposed to the British rule and started an intense non-cooperation movement against them. Led by him, the people boycotted English education, mill made cloths and other imported goods. The Kuka followers actively propagated the civil disobedience.

All followers of satguru are distinguished by the white dress, straight and pressed turban and a woolen rosary. They were required to wear the five symbols of Sikhism, with only exception of the Kirpan (sword). However, they were required to keep a Lathi (a bamboo stave) with them.

#Sri Satguru Ram Singhji#indianculture#arts and culture#groupexam#iascoaching#inkariasacdemy#chennai#annanagar

0 notes

Video

youtube