#Key Filmmaker | Post-War Era

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

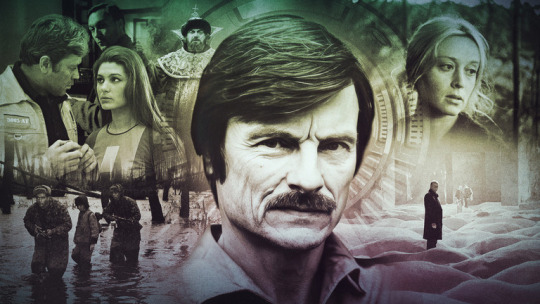

The Father of Modern Arthouse: How Renowned Russian Director Andrey Tarkovsky Transformed World Cinema

The Soviet Union's Key Filmmaker of the Post-War Era Laid the Foundation for the Kind of Output taken for Granted by Movie Lovers Today

— April 28, 2023 | RT

In the history of world cinema, the Soviet Union had two standout periods – the 1920s, during the boom of avant-garde cinema, and the late 1950s and early 1960s, during the "Khrushchev Thaw" (which was named for the opening up of society under the eponymous Nikita, after the years of terror under Joseph Stalin).

While the legendary Sergei Eisenstein, and other giants of the pre-war period, developed techniques that influenced the filming and montage of modern blockbusters, pictures of the latter period inspired arthouse genres.

Among the many post-war Soviet film directors, Andrey Tarkovsky had the greatest impact on world cinema. In 2018, the term “tarkovskian” – describing his unique “slow” and meditative style – was added to the Oxford Dictionary. Since Tarkovsky’s death in 1986, the influence of his cinematic style has spread from international film festivals to rock music clips and even video games.

Tarkovsky has a complicated reputation. His movies are often called “slow” and “boring." However, he remains the only Russian filmmaker of the second half of the 20th century whose work has become a yardstick for representatives of arthouse cinema, and whose name has inspired a search for a successor – for example, Mexican filmmaker Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and the Russian Andrey Zvyagintsev have both been called the “new Tarkovsky.”

What is it that makes Tarkovsky and his work so unique?

War, Home, and First Films

He was born in 1932. His father was poet Arseny Tarkovsky and his mother Maria – who later became the main character of one of his most prominent films, ‘The Mirror’ – was descended from the Dubasov noble family. She also attempted to write, but didn’t manage to build a literary career. Citing a “lack of talent,” she destroyed all her manuscripts.

Although Tarkovsky spent most of his life in Moscow, he was born in the village of Yuryevets in the Ivanovo region (about 500km northeast of the capital). After World War Two broke out, he was evacuated there with his mother – by that time his father had left the family. They lived in the village for just two years, but the wooden house would later reappear in ‘The Mirror’ as a symbol of an idyllic childhood. Throughout his life, Tarkovsky was haunted by the utopian image of “home.” In his films, a happy domestic life exists only in dreams (e.g., the central character's “lost” younger years from ‘Ivan's Childhood’) and memories. Meanwhile, Tarkovsky’s adult heroes often leave home (‘Solaris’), search for it (‘Nostalgia’), or destroy it (‘Sacrifice’).

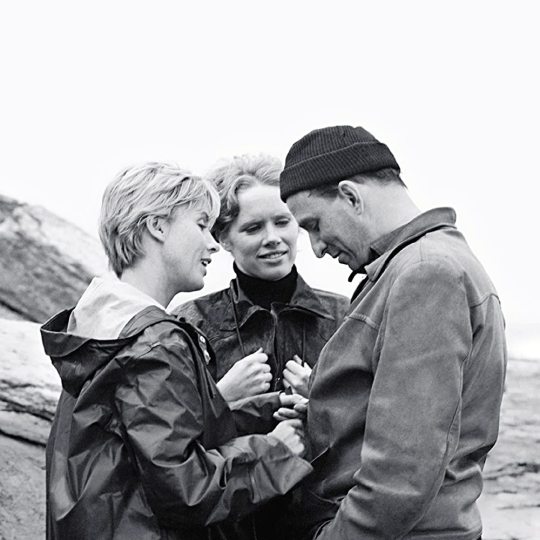

Andrei Tarkovsky © Sputnik/Alexander Makarov

In 1954, Tarkovsky entered the VGIK – the USSR’s most famous film institute. The beginning of his studies coincided with the Thaw period of cinema, which was radically different from previous Soviet movie eras. Young filmmakers who had gone through the war, or encountered it as children, were at the center of this new wave. During the Khrushchev years, the traditions of Stalin-era war cinema were reimagined. Similar processes occurred in other countries that contributed to the victory in WWII. The new motion pictures focused not on soldiers and battles, but on the unseen victims of the war for whom there was no place in Stalin's movies.

In the same year as Tarkovsky was admitted to VGIK, French critic and future film director Francois Truffaut published an article titled ‘A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,’ where he formulated the Auteur Theory. Truffaut described how the filming process in earlier times was managed by producers and screenwriters, but how the director had become the key figure on the set, determining what to shoot and, most importantly, how the footage would be edited. The ‘auteur’ could be a director with an individual style or, as Tarkovsky said, an artist whose personality is “so significant that it determines the artistic qualities of the work.” Yet Tarkovsky was even more radical in his views on the nature of cinema than the French critics. He insisted that ‘auteur’ is a “qualitative concept” stating that, “good cinema is ‘cinema d'auteur.’ A good director is one who has a strong individuality and particular views on the phenomena of life.”

All that remains from Tarkovsky’s student period are several short films and his diploma work ‘The Steamroller and the Violin,’ which is thematically and stylistically close to Thaw cinema. It tells a story of friendship between a child violinist and a steamroller machine driver. Compared to the director's mature works, this traditional and realistic featurette is often relegated to the background. However, this ‘student’ film first shows us the artist-protagonist who is to become the focal point of Tarkovsky's work. His semi-autobiographical characters that grow up alongside their author – from the little musician of this debut work to the elderly writer from his final film, ‘The Sacrifice’ – invariably face the unknown, whether it is a socially-distant driver of a steamroller, the wish-granting room of ‘Stalker,’ or the divine revelation of his last movie.

Tarkovsky did not consider ‘The Steamroller and the Violin’ a great success and did not like talking about it. However, the film did its job – the director graduated from the institute with honors.

'The Steamroller and the Violin' (1960) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

Global Recognition and First Conflicts With The Authorities

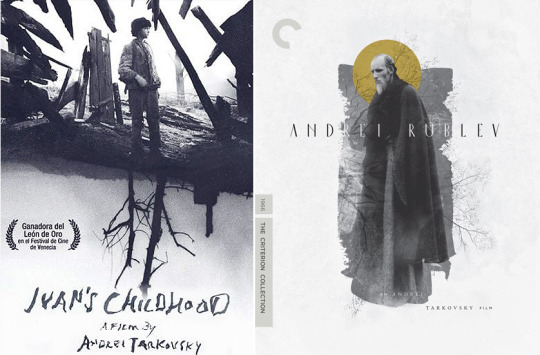

Tarkovsky's first full-length picture was the war drama ‘Ivan’s Childhood.’ Initially, this film – based on the story ‘Ivan’ by Vladimir Bogomolov – was shot by another director. However, Mosfilm Studio found that version “unsatisfactory.” It was particularly criticized for the free treatment of the original text in which the young partisan, Ivan, who was killed at the end of the story, instead survived in the movie and went on to volunteer in the Virgin Lands campaign. This new ending wasn’t approved by Bogomolov and completely contradicted his idea. The writer recalled how he contacted the newspaper which published an article about child partisans with an appeal, “Young heroes, respond!” As Bogomolov found out, no one responded – because no one had survived.

Tarkovsky was given limited time and the remaining budget to shoot his version. He significantly reworked the original text, focusing on the inner world of the child partisan Ivan. Dreams became key to his story. In these dreams, the boy sees his lost mother and lives a happy childhood. In ‘Ivan's Childhood,’ the ‘real world’ doesn’t hold back the dark, repressed desires of the subconscious. On the contrary, this real world is dark and cruel. As film critic Oleg Kovalov writes, the paradox of war is that “the poor child’s striving towards harmony, light, peace, and kindness become an almost shameful desire, a secret perversion.”

‘Ivan's Childhood’ won Tarkovsky the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and brought him worldwide fame. At that time, ‘Thaw cinema’ was popular abroad and often received prizes at international festivals. In 1958, M. Kalatozov's war melodrama ‘The Cranes are Flying’ won the Palme d'Or in Cannes, and in 1961, G. Chukhray's film ‘Ballad of a Soldier’ won the BAFTA Award. Like ‘Ivan's Childhood,’ these movies looked at the war in a new way, moving away from heroic narratives and turning to the stories of its victims.

Tarkovsky's next movie was a medieval drama about the great painter of icons – Andrey Rublev. Despite a deep immersion in the medieval era, the director wasn’t obsessed with accurately reflecting the realities of the 15th century. In Tarkovsky's movie, Rublev, whose biography is practically unknown, is shown as an artist working in the horrible conditions of internecine wars, famine, and surrounding violence. His Rublev is a far cry from the ‘artist inspired by the people’ – the image approved by party officials. Tarkovsky has Rublev go through a loss of faith in people so that he may regain it in the finale after meeting the young bell caster Boriska. In an interview unpublished during his lifetime, Tarkovsky says that “the artist is the conscience of society” and the person who’s most sensitive to changes.

'Ivan's Childhood' (1962); 'Andrei Rublev' (1966) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

During the production of ‘Andrey Rublev,’ a conflict first emerged between Tarkovsky and the Soviet officials who oversaw the studios. The movie was constantly edited, the major scene depicting the Kulikovo Battle didn’t get the required funding (after the film’s release, the press criticized the director for cutting this scene during final edits), and Tarkovsky was accused of excess violence. Eventually, the work was cut by 30 minutes and allowed only limited release three years after it was completed.

Aesthetic Dissident

After two movies focusing on past experiences, the events in Tarkovsky’s next picture unfolded on a space station in the near future. Despite the science fiction genre, ‘Solaris’ – a free adaptation of the novel by Stanislaw Lem (the author wasn’t satisfied with the film and said that Tarkovsky shot ‘Crime and Punishment,’ not ‘Solaris’) – is based on familiar themes: the conflict between reality and fantasy, human memory, and loss of home.

Tarkovsky didn't like genre films and entertainment movies, but science fiction provided a greater sense of allegory than historical events. While filming ‘Solaris’ and ‘Stalker,’ he could explore ideas that interested him while also feeling less pressure from the Communist Party. In her book on Tarkovsky, film critic Maya Turovskaya wrote that Tarkovsky was not a political, but an “aesthetic” dissident, and having minimal outside interference in his work was more important for him than political and economic freedom.

In his next movie, Tarkovsky wanted to explore the phenomenon of memory and to set himself free from the conventions of any genre. Initially, ‘The Mirror’ was planned as an interview film in which the filmmaker’s mother was asked a variety of questions – ranging from her own life to the Vietnam War – while being filmed with a hidden camera. Tarkovsky soon abandoned this idea and made a feature film, but one that was unique in its form.

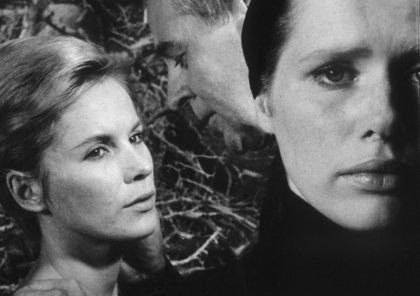

'Solaris' (1972); 'Mirror' (1975) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

Tarkovsky's co-author, screenwriter Alexander Misharin, remembered the first screening of ‘The Mirror’ by the chairman of the USSR State Committee for Cinematography who remarked, “Surely, we have freedom of creativity. But not to such an extent!” ‘The Mirror’ was in many ways the opposite of the director's previous film. The action descended from space to earth, and instead of a clear plot, it was based on a fragmented narrative imitating human memory where characters and events are layered on top of each other. For example, the main character’s mother and wife are played by one actress, which confuses the viewer and blurs the lines between childhood and recent events.

Instead of a simple, almost non-existent plot, the film is based on visual and thematic ‘rhymes’, which is why ‘The Mirror’ is often called “poetic cinema.” The film is based around the memories of a dying man in whose mind wartime childhood memories blend into the landscapes of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, historical chronicles rhyme with personal experiences, and his mother’s memories intertwine with his own.

By the decision of the State Committee for Cinematography, the film was not widely distributed in the USSR, although it was sent to Cannes. The film’s “unfriendly” exploration of consciousness and memory sealed Tarkovsky's status as an ”aesthetic dissident."

The director’s last movie in the USSR was ‘Stalker’ – a fantastic parable about the journey of the three main characters to a place where secret wishes are fulfilled. The filming process was accompanied by a series of misfortunes: the script was rewritten over ten times, the movie had to be reshot due to a technical issue in which several thousand meters of film were improperly developed and ruined, and Tarkovsky suffered his first heart attack. Stalker acquired the reputation of being a ‘cursed movie’ when, following the premiere, several members of the crew died within a short time, including the director's friend and one of his regular actors, Anatoly Solonitsyn, who played the role of the Writer.

'Stalker' (1979) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

After the futuristic ‘Solaris’ and the experimental ‘Mirror,’ ‘Stalker’ seems almost ascetic. Tarkovsky’s late works increasingly gravitate towards compositional simplicity and limited space – “finding a reflection of infinity in a small space.” For example, the characters in ‘Stalker’ don’t have real names, only nicknames (Stalker, Writer, Professor), and the picture’s post-apocalyptic world is much closer to the stagnant Soviet Union than the ‘city of the future’ from ‘Solaris.’

Conflict With The Authorities

Tarkovsky shot only seven full-length films in his 25 years of filmmaking, but up to the very end of his life, he had many creative plans. One of these was to work on a film in Italy – and in fact, this turned into the movie ‘Nostalgia.’ Tarkovsky waited for permission to start filming for over three years. He finally obtained it with the help of Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra, who had some influence over Soviet officials. With Guerra, Tarkovsky began writing the script about a man traveling through Italy.

In 1980, Tarkovsky went to Italy to prepare for filming. While there, he had the chance to compare two styles of filmmaking – Soviet and Western. Tarkovsky didn’t have a preference for either and pointed out the shortcomings of each. While capitalist society gave the artist full freedom of expression, it also provided fewer opportunities for making his idea come to fruition.

In many ways, ‘Nostalgia’ anticipated Tarkovsky’s own future fate. The main character is a Russian writer who, like the protagonists of his previous films, travels not so much through Italy as through the realms of his own memory. Tarkovsky reveals the inner experience of emigration where the protagonist is stuck between two worlds, fully belonging to neither of them.

Tarkovsky did not initially plan on permanently leaving the USSR. Despite the fact that he and his wife were allowed to go to Italy, his son and mother had to stay in the USSR. Andrey Tarkovsky Jr. later said that they were left as “hostages” in the Soviet Union to prevent his father from permanently emigrating to the West. What exactly happened remains unknown, but apparently the leadership of the State Committee for Cinematography decided that Tarkovsky had become a so-called “non-returnee” and that he did not plan on coming back to the USSR. His name was banned from print in the USSR, and the Soviets withdrew from the production of ‘Nostalgia.’

'Nostalgia' (1983) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Sovinfilm

Tarkovsky's letters to the general secretaries of the CPSU Central Committee Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, in which he asks to work and live in Italy with his family for three years, have been preserved. The filmmaker emphasized that his last picture, ‘Nostalgia,’ was about “homesickness experienced by a Soviet person temporarily finding himself abroad” and that he had no plans to emigrate.

While Tarkovsky worked in the USSR, his relations with censors got progressively worse. At the premiere of ‘Nostalgia’ at the Cannes Film Festival, the Soviets, represented by film director Sergei Bondarchuk, went to great lengths to make sure that Tarkovsky would not receive the main prize. The confrontation ended in an open conflict. In a letter addressed to Secretary General Chernenko, Tarkovsky stated 11 points that demonstrated unfair censorship of his work. Among these were: illegal restrictions on the public release of his films, boycotts by USSR awards committees and film festivals, no press coverage, and the sabotage of ‘Nostalgia’ in Cannes. The betrayal he experienced in Cannes and in his homeland convinced Tarkovsky not to return home. In the summer of 1984, Tarkovsky announced his decision to stay in the West.

Farewell

‘The Sacrifice’ became Tarkovsky's last movie, most of which was filmed in Swedish. Tarkovsky was invited by the Swedish Film Institute, which covered most of the film's expenses. He was a big fan of the great Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, who lent the Russian director part of his own film crew: Bergman actor Erland Josephson played the leading role, cinematographer Sven Nykvist, who worked with Bergman on all his main films, was the cameraman, and the filmmaker’s son, Daniel Bergman, was his assistant. Moreover, Josephson and Nykvist invested some of their own funds into the film, becoming its co-producers.

By the time filming was over, Tarkovsky was diagnosed with lung cancer. ‘The Sacrifice’ – the story of an aging man who sacrifices his regular life and burns down his house to prevent a nuclear war – is often called ”prophetic." It stands as both the final testament of the dying filmmaker and a prophecy of the Chernobyl disaster that occurred just a few weeks before the premiere.

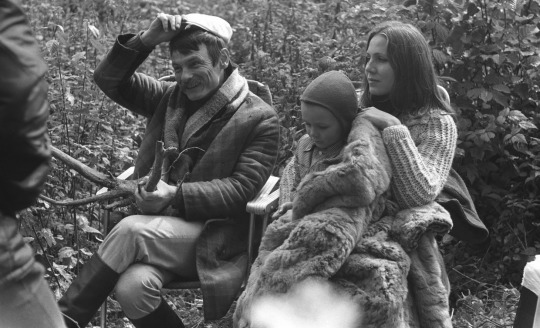

Film director Andrei Tarkovsky on the set of the movie 'Stalker' in 1977. In the picture: Andrei Tarkovsky and Larisa Tarkovskaya. © Global Look Press/Igor Gnevashev/Russian Look

Five years after Tarkovsky’s departure from the USSR, his sixteen-year-old son was allowed to visit his sick father. According to Alexander Gordon, a friend and co-author of Tarkovsky’s early works, party officials knew about Tarkovsky's diagnosis, but for a long time did not disclose it to his family. At that time, Tarkovsky’s previously banned movies were once again released in the Soviet Union.

Tarkovsky died at the end of 1986, at the age of 55. A few days later, the USSR State Committee for Cinematography released an obituary, expressing “bitterness and regret” that the filmmaker had worked away from his homeland in his final years.

Tarkovsky was buried at the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery near Paris – the final resting place of many Russian émigrés, writers of the Silver Age, and members of the White Movement.

#Renowned | Russian 🇷🇺 | Director | Andrey Tarkovsky#The Father of Modern Arthouse#Soviet Union#Key Filmmaker | Post-War Era#Laid | Foundation#Movie Lovers#Global Recognition#Conflicts#Authorities#War | Home | First Films#Aesthetic Dissident#Farewell

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of Russia’s most famous 20th-century novels has returned to the Silver Screen. Infamously difficult to capture as a motion picture (more mystical observers even speak of a curse), Mikhail Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita” is back, reinterpreted by American-Russian filmmaker Michael Lockshin. The new movie stars Evgeny Tsyganov and Yulia Snigir in the titular roles and features German actor August Diehl (Gestapo major Dieter Hellstrom in Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds”) as the story’s demonic character Woland. Meduza reviews the controversy surrounding the film’s director and funding, the book’s cinematic history, and Lockshin’s adaptation.

The political controversy

Michael Lockshin’s “The Master and Margarita” averages an impressive 7.9/10 rating with more than 43,000 reviews at KinoPoisk and leads Russia’s box office in its opening week after earning 57.3 million rubles ($640,000) on its first day in theaters, but the director was making enemies before his film ever sold a single ticket. Self-described patriots denounce Lockshin as a Russophobe, a traitor, and a neoliberal besmircher of the intrepid Soviet secret police. They call him a hypocrite, too, in light of the fact that this new adaptation of Bulgakov’s classic was made (in 2021, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine) with 800 million rubles ($8.9 million) from Russia’s Cinema Foundation, the state’s key funding agency for the domestic film industry.

Lockshin, who now resides in the United States, declined to answer Meduza’s questions about the backlash in Russia, saying he’s not yet ready to comment on the situation. On Telegram, pro-war channels have circulated screenshots of Facebook posts that are now hidden from non-friends where Lockshin shared independent reporting about the war in Ukraine, wrote that he’s donated to Ukrainian organizations, warned that future generations of Russians will be paying reparations for the “tragedy they brought to Ukraine,” and compared the Putin regime to Nazism in Germany.

State propagandist Tigran Keosayan has advocated criminal charges against Lockshin, while Trofim Tatarenkov, a host on Russia’s state-run Sputnik radio (who admits that he hasn’t even seen Lockshin’s movie), called the filmmaker “scum” and fondly remembered how such “enemies of the people” were shot during the Stalinist era.

Previous adaptations

In May 2016, poet and literary critic Lev Oborin wrote an essay for Meduza answering several “questions you’re too embarrassed to ask” about Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita,” including the most shameful of all: Can I just skip the book and watch a movie version instead? The short answer is, yes, you can always skip the book. In fact, unless you’re a student or some other kind of hostage, you can skip the movies, too. But since you asked, there are at least two previous screen adaptations of “The Master and Margarita” worth knowing about.

The better-liked version, at least until now, has been Yuri Kara’s 207-minute film, made in the mid-1990s but not released until August 2011. Meanwhile, in 2005, Vladimir Bortko created a miniseries for Russian television that was criticized for uneven casting and even worse special effects. Unfortunately for Bortko, the 10 episodes drew deeply unfavorable comparisons to his beloved 1988 adaptation of Bulgakov’s “Heart of a Dog.”

It’s also tempting to contrast Bortko’s miniseries with Kara’s adaptation — particularly how the two portrayed one of the novel’s most visually scandalous scenes: Satan’s Grand Ball. Filmed almost a decade later and made for TV, the sequence in Bortko’s series “looks almost puritanical” compared to Kara’s film, noted Lev Oborin. In raw terms of nudity and violence, this assessment is hard to contest:

youtube

So, is Lockshin’s adaptation any good?

Anton Dolin (a prominent Russian film critic who might be best known to casual Internet users as the interviewer who provoked Ridley Scott into saying, “Sir, fuck you. Fuck you. Thank you very much. Fuck you, go fuck yourself.”) liked Lockshin’s adaptation quite a bit. In a review published by Meduza, Dolin writes that the film “manages to retain the sharpness of the original source, which mocks Soviet power, and at the same time offers the viewer an innovative perspective on a classic text.”

Dolin praises Lockshin’s “Hollywood flourishes” and his capacity to juggle the book’s “genre and intonation incompatibility,” which has plagued past interpretations. The new adaptation brings a “circus element” to the story without sacrificing the script’s “rigidity,” says Dolin, while also “condensing the vastness of Bulgakov's novel into a coherent and clear narrative.” (You’ve been warned, formalists.)

Lockshin’s film takes some liberties with Bulgakov’s classic. For example, in the novel, the Master character doesn’t emerge until the middle of the book, leaving the reader to wonder about the title. In the new film, however, the main plotline belongs to the love story between Margarita Nikolaevna (the unhappily married wife of a Soviet functionary) and a writer she calls the Master. According to Lockshin’s script (which he co-wrote with Roman Kantor), the secondary narrative involving Pontius Pilate’s trial of Yeshua Ha-Notsri (Jesus of Nazareth) is a play within the story written by the Master and pulled from production by Soviet censors after its opening performance. (In a feat of authenticity unprecedented in modern Russian cinema, the Jerusalem scenes, which comprise roughly 10 minutes of the film, are performed in Aramaic and Latin.) Meanwhile, all the adventures across Moscow involving Woland and his entourage are presented as figments of the Master’s imagination as he slowly loses his mind under state persecution.

As Lockshin has argued in comments promoting the movie, Dolin says Bulgakov’s novel enjoys heightened relevance in contemporary Russia, and the new film makes menacing villains of NKVD executioners while presenting even more revolting characters in the Soviet elites whose conformity and hypocrisy enabled the Stalinist regime.

Dolin praises the decision to cast August Diehl as Woland, the mysterious foreigner whose visit to Moscow sets the plot rolling in the novel. Diehl’s Woland “is a real find,” Dolin writes. The German actor plays the character as “an infernally sarcastic gentleman in black” who resembles Satan “more than the thoughtful, sad wisemen from various Russian interpretations of the same character.”

A cartoonishly scary foreigner, complete with a spooky German accent, Woland turns out to be the creation of the writer’s wounded mind, his alter ego, writes Dolin. The censorship and persecution the character faces in the film are a “chilling reproduction” of mechanisms that resonate more in Putinist than Stalinist Russia, Dolin argues, highlighting some lines that wink boldly at modern-day realities, including nods to Crimea, oil production, and military parades.

Lockshin’s adaptation also features a fantastical version of Moscow that recalls the visionary designs of artists in the Higher Art and Technical Studios, which flourished in the 1920s before crumbling under Stalinism. In this universe, Moscow completed the Palace of the Soviets, altering the skyline in a delirious finale that depicts the city ablaze. This scene, in particular, has upset several state propagandists.

Dolin notes that Margarita is absent from the story for much of the film, but she reappears in the final act as a heroine on her own narrative arc. In the character’s scenes as a witch and then a queen, Lockshin’s intentions and the meaning of the novel’s title finally become clear, says Dolin:

It’s not the imagination of the writer that transforms the grim reality but exclusively the emotion that is capable of elevating you to the heavens, of burning cities, and punishing or pardoning with the mere force of thought. In the end, Lockshin’s film is not about Satan, not about Moscow, not about Pilate, and not about totalitarianism, censorship, or creativity, but about love. It alone makes a person invisible and free.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dystopian themes in the Prequels

“Looking back is helpful in understanding his work. Lucas started out in the 1960’s as an experimental filmmaker heavily influenced by the avant-garde films of the San Francisco art scene. Initially interested in painting, he became an editor and visualist who made abstract tone poems. His first feature, THX 1138 (1971) was an experimental science fiction film that presented a surreal, underground world where a dictatorial state controls a docile population using drugs. Love and sex are outlawed, procreation is controlled through machines, and human beings shuffle meaninglessly around the system.”

—Anthony Parisi, 'Revisiting the Star Wars Prequels'

The bolded parts in this description correspond with the Coruscant Underworld, the Jedi Order’s code, and the creation of the clone troopers, respectively.

Notably, in THX 1138's setting, emotions such as love and the concept of family are taboo:

I’ve always found it so interesting that Lucas incorporated the dystopian elements of his earlier sci-fi into the Prequels, taking place as they do in the context of the final years of the Repubic, with all its colourful and sumptuous visual spendour. In comparison, the post-apocalyptic ‘Dark Times’ of the Original Trilogy would seem on the surface to be the more outwardly ‘dystopian’ setting of the two—however, the actual story of the OT is a mythic hero's journey and fairytale, complete with an uplifting and transcendent happy ending. The OT's setting may be drained of colour, and its characters may be living under the shadow of the Empire, but as a story it is far from bleak or dystopian in tone. Rather, fascinatingly, it is the pre-apocalyptic era of the Prequels that is presented as the more dystopian storyline:

“On the surface, [The Phantom Menace] is an optimistic, colorful fantasy of a couple of swashbuckling samurai rescuing a child Queen and meeting a gifted slave boy who can help save the galaxy from the slimy Trade Federation and its Sith leaders. But beneath that cheerful facade is a sweatshop of horrors.” —Michael O'Connor, 'Moral Ambiguity: Beyond Good and Evil in the Prequels'

This is referring to the state of the galaxy during the Prequels era, including the fact that slavery is known to exist, but is largely ignored by the Republic and the Jedi alike due to being too economically inconvenient to combat. It also refers to how the Jedi of the Old Order come across as cold and distant atop their ivory tower on the artificial world of Coruscant, far removed not only from the natural world but also from the true realities of the people they claim to serve. And then there is the additional revelation in Attack of the Clones that love and family are 'outlawed' within the Jedi Order, creating an environment in which their own 'Chosen One' is unable to flourish, leaving him vulnerable to the Dark Side. Finally, there's the fact that the characters end up so distracted by fighting a civil war (something that goes against their own principles and involves the use of a slave clone army in the process), that they are blinded to the entity of pure evil that is guiding their every move...until it is too late.

“Without a clear enemy, the Jedi Order, the Galactic Senate, the whole of the Star Wars galaxy bickers and backstabs and slides around the moral scales. But there is one benefit to Palpatine’s pure evil crashing down upon the galaxy; against its oppressive darkness, only the purest light can shine through.” —Michael O'Connor, 'Moral Ambiguity: Beyond Good and Evil in the Prequels'

If anything, the Dark Times allows for the OT generation's acts of courage and heroism to flourish and succeed, because they are not hampered by the Old Jedi Order's restrictive rules, nor by its servitude to the whims of an increasingly corrupt Republic—so corrupt, in fact, that by the time of RotS, it is practically the Empire in all but name. Indeed, one of the key features of the Prequels, and what makes them so tragic, is that the characters are already living in a dystopia...they just don't know it.

There is, paradoxically, a level of freedom to be found in the midst of the Dark Times which had not been possible during the Twilight era, which allows Original Trio to rise above the tragedy that befell their predecessors. They are able to act as free agents (not as slaves of a corrupt government), serving only the fight for the liberation of all the peoples of the galaxy (not just citizens of the Republic), and are likewise free to live (and love!) on their own terms. Free to act on their positive attachments to one another, without having to hide the truth of their feelings. It's particularly telling that *this* is, above all, what makes the Prequels era so dystopian—the characters' inability to freely and openly participate in normal familial human relationships.

#the prequels#original trilogy#pt x ot#the skywalker saga#the real skywalker saga#lucas' saga#lucas' influences#THX 1138#the twilight of the republic#vs#the Dark Times#the jedi order#jedi discourse#Prequels appreciation#the prequels era as dystopia#the prequels as tragedy#the original trilogy as fairytale#original trilogy era as fairytale#slavery vs. freedom#the dark is generous and it is patient and it always wins#but it is also the context in which the light shines more brightly

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this date in 1990 “The Hunt For Red October” was released!

Capt. Borodin: “The crew know about the saboteur. They are afraid.”

Marko Ramius: “Well, that could be useful when the time comes.”

Director:John McTiernan

1st AD:Jerry Ballew

Cinematographer:Jan de Bont

Camera operator:Roger Gebhard

1st AC:Cal Roberts

Production Designer:Terence Marsh

Gaffer:Ed Ayer

Key grip:Larry J. Aube

Dolly grip: Michael J. Coo

This is one of my favorite movies so today we’re going on a deep Dive! Dive! Dive! on how this group of dedicated filmmakers brought this movie to life.

The producers originally wanted Kevin Costner for the lead, but Costner had other ideas.

As producer Mace Neufeld explained in a behind-the-scenes DVD feature, "I'd gotten quite friendly with Kevin Costner, and I went to Kevin about playing Jack Ryan. But Kevin was up to his neck, and very enthusiastic, about doing this ... this buffalo movie. And I said, 'You'd rather do a buffalo movie?'".

This was Alec Baldwin’s first big budget starring role throwing himself face first into the role spending time with C.I.A agents and spending the night 600’ underwater in a submarine. He also recommended he personally do the helicopter drop into the ocean. Baldwin accepted the role of Jack Ryan because Harrison Ford turned it down. Cast member Sam Neill also benefited from Ford's refusal three years later by being cast in the lead role of Jurassic Park (1993). Interestingly, Baldwin asked for a big pay increase for the sequel, to which the producers allegedly replied, "For that price, we could get Harrison Ford." Baldwin held his ground and the studio agreed to the fee, but for Ford instead of Baldwin for “clear and present danger”

Sean Connery was a last-minute replacement. The film had been in production for two weeks when word came that Klaus Maria Brandauer (Out of Africa), the Austrian actor who'd been signed to play the rogue Soviet sub commander Marko Ramius, couldn't do it after all because of a prior commitment. Connery took the part instead, needing only one day for rehearsal. Coincidentally, he and Brandauer had acted together in 1983's “Never Say Never Again” and would reunite again for 1990's “The Russia House”, which was shot shortly after The Hunt for Red October.

Mancuso: The hard part about playing chicken is knowin' when to flinch.

"I had reservations about it," Connery told an Associated Press reporter upon the film's release. "I thought this kind of Cold War intrigue might be dated because of recent events(the fall of the U.S.S.R). It turned out that the studio had failed to fax the first page of the script, which explained that it took place before Gorbachev." This is probably why no one ever uses fax machines anymore. After being faxed the script, Sir Sean Connery initially turned the role down on the basis of the plot being unrealistic for the post-Cold War era. Whoever sent the fax neglected to include the foreword, explaining the movie as historical. Once he received the foreword, Connery accepted the role.

After consulting with the hair department behind director John McTiernan's back, Sir Sean Connery arrived on-set for his first day of principal photography with his hairpiece incorporating a ponytail. Several years later, once Connery's potential influence had greatly waned, McTiernan stated in an interview with Sight & Sound Magazine that he was "f---ing livid" with Connery, and that the Scottish actor tried to use his considerable heft with the studio, going over the director's head to pass the alteration with producers. It seemed as though Connery was to get his way until midway through the second day's shooting, when director of photography Jan De Bont started laughing while reviewing the dailies, remarking to Connery that his ponytail looked like "a limp, swinging d--k." This soon became a meme among the crew, and by the end of the second day, Connery was so upset at the mockery, he relented, having the hair department remove the alteration and forcing the re-shoot of a key scene. McTiernan joked that the reported cost of the hairpiece, approximately $20,000, was mainly down to the cost of those subsequent re-shoots.

Jeffrey Pelt: “Listen, I'm a politician, which means I'm a cheat and a liar, and when I'm not kissing babies, I'm stealing their lollipops, but it also means that I keep my options open.”

Screenwriter Larry Ferguson played the role of C.O.B. [Chief (Petty Officer) of the Boat] on the U.S.S. Dallas. He didn’t know he had been cast till he saw his name on the cast list and quickly hired an acting coach having not acted in over 16 years, he quickly started rewrites giving his character more screen time.

The film got an uncredited rewrite—including all of the Russian dialogue—from veteran filmmaker John Milius. The writer of “Apocalypse Now”, and director of “Conan the Barbarian”, and “Red Dawn”—who had directed Connery in 1975's “The Wind and the Lion”—told an interviewer in 2003 that the rumors of his involvement with The Hunt for Red October were true. He said he added speeches for Connery's character ("Make it about me," the actor supposedly told him), and that he "wrote all of the Russian stuff—everything that's Russian in that movie."

In one of the most clever ways I’ve seen a movie ditch the subtitles, this film begins with the actors speaking Russian with English subtitles. As the camera slowly dollies to the mouth of actor Peter Firth he casually switches in mid-sentence from Russian to English on the word "Armageddon", which is the same spoken word in both languages. After that point, the Soviets' dialogue is communicated in English.

During filming, several of the actors portraying U.S.S. Dallas crewmen took a cruise off the coast of San Diego on the USS Salt Lake City (SSN-716) a real Los Angeles-class submarine. To train for his role as the Dallas' commander, Scott Glenn. The real commander Thomas Fargo of the Salt Lake City ordered his crew to treat Glenn as equal rank, first giving reports to him, then give the same report to Glenn. Glenn based his performance of Mancuso on Commander Fargo, giving orders in a calm even voice, even in tense situations, saying "whatever good happened in the performance, basically I owe to now Admiral Fargo, thank you sir."

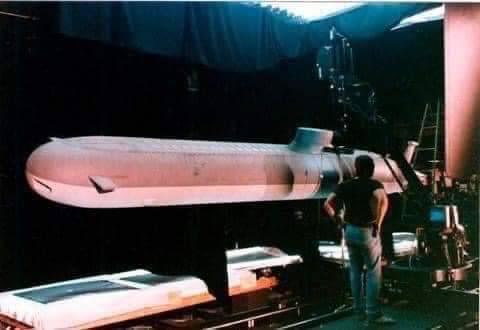

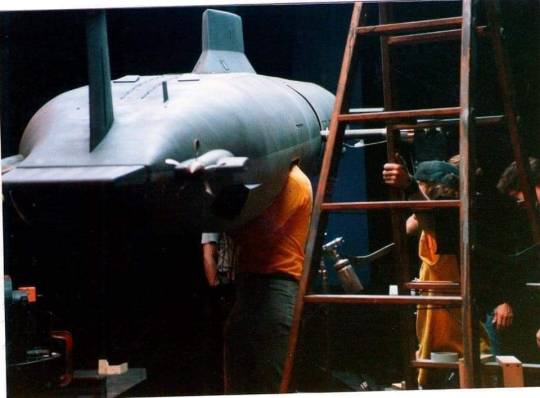

Made before sophisticated CGI became the norm in filmmaking, the film's opening sequence featured a long pull-out reveal of the immense titular Typhoon-class sub. It included a nearly full-scale, above-the-water-line mockup of the sub, constructed from two barges welded together. Since they didn’t have permission to go out to open ocean they were forced to shoot in Long Beach harbor to create the wake of the open ocean they had boats circling the barge to create waves.

Production designer Terence Marsh and Cinematographer Jan de Bont didn’t want to confuse the audience so they gave each country's submarine its own background color: Soviet submarines, such as Red October and V.K. Konovalov, had interiors in black with chrome trim. American ships, such as Dallas and Enterprise, had grey interiors. To help the audience quickly grasp which sub's interior they were seeing as the movie jumped from scene to scene and sub to sub, the filmmakers also created a subtle lighting scheme: blue for Red October, green for the Alfa class "V.K. Konovalov", and red for Dallas.

During filming in 1989, the U.S.S. Houston, which doubled for the U.S.S. Dallas in the movie, snagged the tow cable between the commercial tugboat Barcona and a barge, sinking the tugboat ten miles off Long Beach, California. One crewman unfortunately drowned, and two more were rescued.

On stage for the sub interiors two 50-square-foot (4.6 m2) platforms housing mock-ups of Red October and Dallas were built, standing on hydraulic gimbals that simulated the sub's movements. Connery recalled, "It was very claustrophobic. There were 62 people in a very confined space, 45 feet above the stage floor. It got very hot on the sets, and I'm also prone to sea sickness. The set would tilt to 45 degrees.

I asked the Dollygrip on the film and crew stories member Micheal Coo about his experience on the and he shared this with us.

“ I’ve got a story for you...

We were shooting in a real submarine and doing a tracking shot down a long corridor. Now about every 15 feet is a bulkhead that you have to step over and make sure you don’t hit your head on the top. We are tracking on a peewee dolly, raised up on track to clear the bulkheads, chasing Sean Connery down the corridor. While chasing Sean, Jan Debont yells cut cut cut, and stands up. There’s no way I could stop on a dime and Jan stood up right before one of the bulkheads. He hit his head so hard he flew over the top of me and I went under him with the dolly. His head sounded like a church bell ringing in the submarine. Since Jan Debont and Sean Connery didn’t get a long so well Sean laughed his ass off at Jan laying there on the floor saying “Fucking Hell Shit Michael, I said cut!!!”

The miniature “underwater” scenes were shot and built by I.L.M and the talented model makers from BOSS films Gregory Jein, John Eaves, Ron Gress and Alan McFarland, they filmed using smoke to simulate underwater with a model sub connected to a 12 cable marionette style frame, giving precise, smooth control for turns the same technique was used for the robot aliens in the film “Batteries not included”. To get the lens to “scrape the paint” of the model to make it feel life sized the crew used mirrors lined up perfectly and the camera lens shoot into the mirror getting the image much closer then it would have been possible for the camera. With Computer generated effects, in their infancy, cgi was used for creating bubbles and other effects such as particulates in the water.

Navy recruiters set up booths in some theater lobbies for people to sign up to join the service, or to at least look into it. The Pentagon hoped that this movie would do for the submarine service what Top Gun (1986) did for Naval aviation.

When the movie was first released on VHS in 1991, the tapes were red.

Capt. Marko Ramius: I'm reminded of the heady days of Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin when the world trembled at the sound of our rockets. They will tremble again at the sound of our silence. The order is engage the silent drive.

If you can help identify any crew members please comment, thanks for reading

Via Diego,IMDb, YouTube,MCGA. Special thanks to Dolly Grip on the film Michael Coo and miniatures paint expert Bruce Hazumi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Rich Heritage and Growing Popularity of Khmer Movies

Introduction

A Glimpse into the History of Khmer Cinema

The history of Khmer cinema stretches back to the mid-20th century, during which it experienced a flourishing period known as its golden age. Between the 1950s and 1970s, the Cambodian film industry produced hundreds of movies, marked by strong storytelling and distinctive artistic flair.

The Golden Age (1950s–1970s)

This era was marked by a surge of creativity. Films like “Puthisen Neang Kongrey” and “Sovannahong” were household names, celebrated for their intricate plots and musical scores that resonated deeply with audiences. This period was spearheaded by influential figures such as King Norodom Sihanouk, who was not only a king but also an avid filmmaker.

Impact of the Khmer Rouge

The golden era came to an abrupt halt during the reign of the Khmer Rouge (1975–1979). This brutal regime sought to erase Cambodia's cultural identity, leading to the decimation of the film industry. Film reels were destroyed, and many artists and filmmakers faced persecution or death, creating a void that would take decades to fill.

Resurgence of Cambodian Films Post-1990s

The end of the Khmer Rouge era allowed for the slow rebuilding of the film industry. In the 1990s and 2000s, directors began re-exploring narratives of loss, hope, and cultural pride, setting the stage for a new generation of Khmer cinema.

New Themes and Modern Storytelling

Post-war films often reflected the pain and resilience of the Cambodian people. Movies like “The Last Reel” captured the struggle of reclaiming lost heritage while new genres emerged, including romantic comedies and supernatural tales that appealed to younger audiences.

Key Genres in Khmer Movies

Cambodian cinema offers a rich variety of genres. The traditional golden age favored dramas and mythological tales, while today’s films are more diverse.

Popular Genres in the Modern Era

Action and Adventure: High-energy films featuring local heroes.

Romance: Heartfelt stories that explore love within the context of Cambodian culture.

Horror: Spooky tales steeped in local folklore, reflecting the nation's fascination with spirits and legends.

Notable Khmer Movies and Their Impact

Several films stand out as milestones in the industry’s history and revival.

Golden Age Classics

“Puthisen Neang Kongrey”: A magical tale rooted in folklore, showcasing the thematic richness of early Khmer storytelling.

“Sovannahong”: Celebrated for its grand visuals and enchanting narrative.

Modern Hits

“The Last Reel”: A story of discovery and legacy, showcasing the enduring spirit of Cambodian film.

“Jailbreak”: A popular action movie that broke into international markets, highlighting the potential of local filmmaking.

Renowned Directors and Producers of Khmer Cinema

Key contributors to both the early and current eras have left indelible marks on Cambodian film.

Pioneers of the Golden Age

Directors like King Norodom Sihanouk and Ly Bun Yim were pivotal in shaping early Cambodian cinema. Their dedication laid the groundwork for the industry’s initial success.

Contemporary Visionaries

Today, filmmakers like Kulikar Sotho and Rithy Panh are known for their poignant narratives that bridge history and modernity. The rise of female directors is also notable, marking a shift toward inclusivity and diverse perspectives.

Challenges Faced by the Cambodian Film Industry

The path to growth for Khmer cinema is not without obstacles.

Economic and Resource Constraints

The industry continues to face financial hurdles, limiting the scale and production quality of films. Budgets are often small, which makes competing with larger film markets difficult.

The Role of Technology and Digital Platforms

The digital era has introduced new avenues for Khmer films.

Streaming Services

Platforms like Netflix and YouTube have provided Cambodian movies with a global stage, making them accessible to audiences who might never have encountered them otherwise.

Conclusion

The journey of Khmer Movies is a testament to Cambodia's resilience and creative spirit. While challenges persist, the progress made in recent decades suggests a bright future, one where Khmer films can share the nation’s unique stories with the world.

FAQs

What are some must-watch Khmer movies?Iconic films include “Puthisen Neang Kongrey” and modern hits like “The Last Reel.”

Who are the leading directors in Khmer cinema today?Directors like Rithy Panh and Kulikar Sotho are at the forefront of contemporary Cambodian filmmaking.

How did the Khmer Rouge affect the film industry in Cambodia?The Khmer Rouge regime decimated the film industry, leading to significant cultural and artistic losses.

Why is folklore important in Khmer movies?Folklore connects movies to the deep-rooted beliefs and traditions of Cambodia, enriching storytelling.

How can international viewers access Khmer films?Streaming platforms like Netflix and YouTube offer an array of Khmer movies.

0 notes

Text

Jake Seal Explains What Makes a Movie Iconic?

In the world of cinema, some movies transcend the realm of mere entertainment and become iconic, leaving an indelible mark on culture and society. But what exactly elevates a film to this legendary status? Film producer Jake Seal, known for his deep understanding of the art of filmmaking, offers valuable insights into the key elements that make a movie iconic. From memorable characters to groundbreaking storytelling, these factors contribute to a film's lasting influence and widespread recognition.

1. Memorable Characters and Performances

One of the most critical aspects that contribute to a movie's iconic status is the presence of memorable characters. According to Jake Seal, characters who resonate deeply with audiences and leave a lasting impact are often the heart of iconic films. These characters are not just well-written; they are brought to life through extraordinary performances that capture the essence of their roles. Think of characters like James Bond, Indiana Jones, or Darth Vader—each has become a cultural symbol, transcending the films in which they first appeared. The actors who portray these characters deliver performances that are so compelling that they become synonymous with the characters themselves, ensuring their place in cinematic history.

2. Groundbreaking Storytelling Techniques

Innovative storytelling is another essential ingredient in the recipe for an iconic movie. Jake Seal emphasizes that films that push the boundaries of conventional storytelling often achieve iconic status. Whether through non-linear narratives, unique plot twists, or the exploration of complex themes, these films captivate audiences by offering something new and different. For example, Quentin Tarantino's "Pulp Fiction" revolutionized the way stories could be told in cinema with its disjointed narrative structure, while Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" set a new standard for visual storytelling in science fiction. These films not only entertain but also challenge audiences to think differently, making them unforgettable.

3. Cultural Relevance and Timeliness

The cultural relevance of a movie at the time of its release can also play a significant role in its journey to becoming iconic. Jake Seal notes that films that resonate with the social, political, or cultural climate of their time often leave a lasting impression. These movies tap into the collective consciousness, reflecting or even shaping societal values and attitudes. For instance, "Gone with the Wind" captured the American South's romanticized history during the Civil War, while "The Godfather" explored themes of power, family, and corruption that were particularly resonant in the post-Watergate era. By addressing timely issues, these films become more than just entertainment—they become cultural touchstones.

4. Enduring Visual and Aesthetic Appeal

Lastly, Jake Seal highlights the importance of a film's visual and aesthetic appeal in achieving iconic status. Movies that are visually stunning or introduce groundbreaking visual effects often leave a lasting impression on audiences. Using innovative cinematography, art direction, and special effects can make a film stand out from the rest. For example, "The Matrix" introduced audiences to the now-famous "bullet time" effect, while "Blade Runner" created a dystopian future that has influenced countless films and TV shows since. These visual elements enhance the storytelling and contribute to the movie's lasting appeal and iconic status.

Conclusion

An iconic movie is the result of a perfect blend of memorable characters, innovative storytelling, cultural relevance, and enduring visual appeal. As Jake Seal explains, these elements work together to create films that not only entertain but also leave a lasting impact on culture and society. Whether through unforgettable performances or groundbreaking cinematic techniques, iconic movies continue to resonate with audiences long after their initial release, earning their place in the annals of film history.

0 notes

Text

What Makes Classic Cinema Timeless and Enduring?

Classic cinema, with its timeless appeal and enduring quality, continues to captivate audiences even decades after its release. There is something magical about watching a movie from the past and being transported to a different era, where storytelling was at its peak and cinematic techniques were groundbreaking. In this blog post, we will explore why classic cinema Christchurch holds such a special place in our hearts, and why it continues to be cherished by film lovers around the world.

The Power of Storytelling:

One of the key factors that make classic cinema Christchurch timeless is its ability to excel in storytelling. Classic movies have a unique way of engaging viewers through compelling narratives that touch upon universal themes and emotions. Whether it's a story of love, loss, or redemption, these films resonate with people across generations. Take, for example, "Gone with the Wind" (1939), a sweeping epic set during the American Civil War. The story of Scarlett O'Hara and her journey through war and love has captivated audiences for decades. The film's powerful storytelling, combined with its larger-than-life characters, has made it an enduring classic.

Memorable Characters:

Memorable characters play a crucial role in the longevity and appeal of classic movies. These characters have become cultural icons, etching themselves into the collective consciousness of film lovers. From the suave and charismatic James Bond to the enigmatic and haunting Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" (1960), classic cinema has given us some of the most iconic characters in film history. It is the depth and development of these characters that make them so relatable and unforgettable. Their struggles, triumphs, and flaws are what resonate with audiences and make them stand the test of time.

Tizeless Visuals and Cinematic Techniques:

Classic cinema is known for its visually stunning scenes and innovative techniques that continue to impress modern audiences. Directors, cinematographers, and production designers of the past have left an indelible mark on the world of filmmaking. Films like "Citizen Kane" (1941), directed by Orson Welles, showcased groundbreaking cinematography and visual storytelling techniques that were ahead of their time. The use of deep focus, unconventional camera angles, and innovative lighting created a visual feast for viewers. These techniques have influenced generations of filmmakers, shaping the way movies are made today.

Enduring Impact on Pop Culture:

Classic cinema has left a lasting impact on popular culture, influencing subsequent generations of filmmakers, artists, and musicians. Many contemporary works pay homage to these beloved films, either through subtle references or direct recreations of iconic scenes. Quentin Tarantino, known for his love of classic cinema, often pays tribute to his favourite films in his own work. In his movie "Pulp Fiction" (1994), he references and reimagines scenes from classic movies like "Psycho" and "The Graduate" (1967). This ongoing influence and reverence for classic cinema demonstrate the enduring relevance and impact these films have had on popular culture.

The Joy of Nostalgia:

Watching classic cinema evokes a sense of nostalgia, transporting viewers to another era and evoking memories tied to specific periods in their lives. For many, revisiting these films brings a sense of comfort and sentimental value. Whether it's a film from their childhood or a movie that reminds them of a particular time in their lives, classic cinema has a way of connecting with audiences on a deeply personal level. Personally, I have fond memories of watching movies like "The Sound of Music" (1965) with my family during the holiday season. Revisiting these films brings back those cherished moments and allows me to share them with future generations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, classic cinema continues to be timeless and enduring due to its powerful storytelling, memorable characters, timeless visuals, enduring impact on pop culture, and the joy of nostalgia it brings. The ability of these films to transcend time and resonate with audiences across generations is a testament to their enduring quality.

So, grab some popcorn, dim the lights, and rediscover the magic of classic cinema Christchurch for yourself. Let us celebrate the timeless beauty of these films and continue to have lively discussions about their impact and legacy.

Classic cinema, with its timeless appeal and enduring quality, continues to captivate audiences even decades after its release. There is something magical about watching a movie from the past and being transported to a different era, where storytelling was at its peak and cinematic techniques were groundbreaking. In this blog post, we will explore why classic cinema Christchurch holds such a special place in our hearts, and why it continues to be cherished by film lovers around the world.

The Power of Storytelling:

One of the key factors that make classic cinema Christchurch timeless is its ability to excel in storytelling. Classic movies have a unique way of engaging viewers through compelling narratives that touch upon universal themes and emotions. Whether it's a story of love, loss, or redemption, these films resonate with people across generations. Take, for example, "Gone with the Wind" (1939), a sweeping epic set during the American Civil War. The story of Scarlett O'Hara and her journey through war and love has captivated audiences for decades. The film's powerful storytelling, combined with its larger-than-life characters, has made it an enduring classic.

Memorable Characters:

Memorable characters play a crucial role in the longevity and appeal of classic movies. These characters have become cultural icons, etching themselves into the collective consciousness of film lovers. From the suave and charismatic James Bond to the enigmatic and haunting Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" (1960), classic cinema has given us some of the most iconic characters in film history. It is the depth and development of these characters that make them so relatable and unforgettable. Their struggles, triumphs, and flaws are what resonate with audiences and make them stand the test of time.

Timeless Visuals and Cinematic Techniques:

Classic cinema is known for its visually stunning scenes and innovative techniques that continue to impress modern audiences. Directors, cinematographers, and production designers of the past have left an indelible mark on the world of filmmaking. Films like "Citizen Kane" (1941), directed by Orson Welles, showcased groundbreaking cinematography and visual storytelling techniques that were ahead of their time. The use of deep focus, unconventional camera angles, and innovative lighting created a visual feast for viewers. These techniques have influenced generations of filmmakers, shaping the way movies are made today.

Enduring Impact on Pop Culture:

Classic cinema has left a lasting impact on popular culture, influencing subsequent generations of filmmakers, artists, and musicians. Many contemporary works pay homage to these beloved films, either through subtle references or direct recreations of iconic scenes. Quentin Tarantino, known for his love of classic cinema, often pays tribute to his favourite films in his own work. In his movie "Pulp Fiction" (1994), he references and reimagines scenes from classic movies like "Psycho" and "The Graduate" (1967). This ongoing influence and reverence for classic cinema demonstrate the enduring relevance and impact these films have had on popular culture.

The Joy of Nostalgia:

Watching classic cinema evokes a sense of nostalgia, transporting viewers to another era and evoking memories tied to specific periods in their lives. For many, revisiting these films brings a sense of comfort and sentimental value. Whether it's a film from their childhood or a movie that reminds them of a particular time in their lives, classic cinema has a way of connecting with audiences on a deeply personal level. Personally, I have fond memories of watching movies like "The Sound of Music" (1965) with my family during the holiday season. Revisiting these films brings back those cherished moments and allows me to share them with future generations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, classic cinema continues to be timeless and enduring due to its powerful storytelling, memorable characters, timeless visuals, enduring impact on pop culture, and the joy of nostalgia it brings. The ability of these films to transcend time and resonate with audiences across generations is a testament to their enduring quality.

So, grab some popcorn, dim the lights, and rediscover the magic of classic cinema Christchurch for yourself. Let us celebrate the timeless beauty of these films and continue to have lively discussions about their impact and legacy.

0 notes

Text

Realism, Greed and Old-versus-New: How Hollywood grew to accept realism as its asset

By Jack Muscatello

On the topic of ‘Realism’ in cinema, the Post-War era made for a fitting time to explore more familiar, and less exaggerated, characters, plots and conflicts that audiences could relate to on a deeper level. Instead of the more flashy operas of the 40s, filmmakers in Europe sought after the “common man”, embracing the mundanity of life as a vessel for telling sophisticated stories about greed, corruption and larger critical angles on society at large. Hollywood was the last to follow this line of thinking and redevelopment, as pointed out by Robert Brustein in the Film Quarterly in 1959. To his eyes, “…considering Hollywood's traditional reluctance to agitate anybody, it was inevitable that the moviemakers would turn to the most inoffensive type. Rather than the Ibsenite form which rigorously exposed the cant, hypocrisy, fraud, and humbug beneath the respectable appearance, Hollywood's realism was to become more akin to Zola naturalism -dedicated to a purely surface authenticity” (Brustein, 25). This “Zola naturalism” encompassed a deeper yet still fundamentally shallow portrayal of everyday, relatable life, taking hold of the industry after the war and, arguably, still continues today.

Two films – Foreign Correspondent and 2023 Killers of the Flower Moon – embody some of this mentality. For Foreign Correspondent, the exaggerated nature of the plot almost removes it from contention for the “Zola” principle of realism, but the nature of John Jones’ realization of the horrors of German sympathy under the surface ironically mirrors the shallow realism at play in Hollywood. To Jones, it was the ultimate trip into a body of spy rings and misinformation. However, the real terror was the impending dread of German aggression, supported by sympathizers hidden right in front of him. This cold truth lends itself to Brustein’s observations, even though the film’s plot leaves much of the “realistic” edge out of it.

Subsequently, a similar film about buried corruption released just last month, Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, and actually follows the men responsible for the corruption. Jones was an outsider, slowly peeking into the chaos. For DiCaprio’s character Ernest, his hand is directly involved in each calculated move to steal from the Osage nation. The “Zola” principle comes into play with Ernest’s surface-level stupidity and simple-nature – no one could suspect him as responsible for the murders – but he is. With the help of his uncle, calculated plans take shape across decades, slowly ripping away at the indigenous land in favor of mountainous oil revenues. Where Brustein’s message aligns is with the film’s tone: Scorsese still seeks to tell his “style” of story, that of the sprawling family crime drama – where theatricality and mystery play front and center. But in Killers, there is only some of that, as the story intentionally removes the mystery in favor of showcasing the horrors committed by the “simple” in front the audience. The theatricality is there at times, but is often removed during key moments to embrace the terror, and thus remove the superficiality of the crime saga. It was real, and in defiance of Brustein’s conclusions, Scorsese somewhat distanced himself from the Hollywood norm to tell this story, with all its brutality on full display.

In this image, Ernest Burkhart marries Mollie in an effort to bring himself closer to the Osage nation – and their oil money.

0 notes

Text

Retrospective: Seijun Suzuki.

Retrospective is a regular series showcasing bodies of work from an extended period of activity by filmmakers of different eras.

Devoted to the region’s film history, contributions and movements within the industries in Asia, the platform focuses on particular profiles, themes and aesthetics to allow audiences to experience past and ongoing cinematic transformations.

On the occasion of 100 years since the birth of singular Japanese director Seijun Suzuki (1923-2017), the Asian Film Archive presents a selection from his vast and colourful filmography.

The seven featured films draw attention to two significant points in Suzuki’s career. The first looks at the gritty, rambunctious crime and gangster films he made at the Nikkatsu studios in the 1960s and his collaborations with action star Jo Shishido. The four works selected from this period start from 1963, with the wild and uproarious Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! and Youth of the Beast—the latter regarded as his breakthrough work and a key influence on the yakuza genre. 1964’s Gate of Flesh is a harsh, yet visually dynamic post-war drama. Lastly, the outrageous and stylish Branded to Kill (1967), notorious for causing Suzuki’s dismissal from Nikkatsu and subsequent blacklisting by the industry.

Making his debut in the mid-50s, Suzuki was a contract director for B-movies, quick and cheap flicks typically screened after the more expensive, prestige pictures. He overcame the gruelling conditions and meagre resources thrown at him, creatively transforming conventions into opportunities for play and experimentation, pushing the form further and further with each new film. Burned by the fallout with Nikkatsu, Suzuki withdrew from cinema. He continued to work in television and only returned to film a decade later.

The second part of this programme represents Suzuki’s comeback with the Taisho trilogy: Zigeunerweisen (1980), Kagero-za (1981) and Yumeji (1991). Produced independently, these works are loosely connected by being set during the Taisho era (1912-1926), an explosive period of artistic and intellectual activity in Japan’s history. Hallucinatory, spectral and dreamlike, these austere masterpieces—markedly different from his earlier career—are nonetheless still bursting with ideas and cinematic fervour.

Energised by the commercial and critical success of his later works, Suzuki continued to make films until the mid-2000s and even had a career as an actor. In 2017, he passed away at the age 93. The legacy of Seijun Suzuki’s body of work is that of an artist whose brilliance and verve could not be restrained. Working within the limitations of structures, his career represents a lifelong mission to reinvent the ecstatic possibilities of the filmic medium.

– Viknesh Kobinathan, Programmer

Retrospective: Seijun Suzuki runs from 6-22 October 2023 at Oldham Theatre. This programme is held in conjunction with Japanese Film Festival Singapore, with support from the Japan Foundation.

Asian Film Archive (affiliated to AMIA, FIAF, SEAPAVAA) Retrospective: Seijun Suzuki. 06-22 October 2023 National Archives Singapore 1 Canning Rise Singapore 179868 Singapore, Singapore

#asian film archive#AMIA#FIAF#SEAPAVAA#cinematographic creation#filmmaking#Japanese Film Festival Singapore#Japan Foundation#filmography#singapore#world day for audiovisual heritage#27 october

0 notes

Text

'Opening Friday, Sept. 15, the Rehoboth Beach Film Society’s Cinema Art Theater presents “Oppenheimer,” a cinematographic masterpiece by director Christopher Nolan that looks into a profound historical event, and “A Compassionate Spy,” the incredible and gripping documentary about a brilliant scientist and his profound impact on nuclear history.

The society is featuring these critically acclaimed films as part of its look back on the Atomic Era which kicked off with a sold-out screening of “Top Secret Rosies” and a discussion with filmmaker LeAnn Erickson.

Set during World War II, “Oppenheimer” sees Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves Jr. appoint physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) to work on the top-secret Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer and a team of scientists spend years developing and designing the atomic bomb. Their work comes to fruition July 16, 1945, as they witness the world's first nuclear explosion, forever changing the course of history. The all-star cast includes among others Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr. and Matt Damon.

Directed by Steve James, “A Compassionate Spy” tells the story of controversial Manhattan Project physicist Ted Hall, who infamously provided nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union, told through the perspective of his loving wife Joan, who protected his secret for decades. Recruited in 1944 as an 18-year-old Harvard undergraduate to help Robert Oppenheimer and his team create a bomb, Hall was the youngest physicist on the Manhattan Project, and didn't share his colleagues' elation after the successful detonation of the world's first atomic bomb.

Concerned that a U.S. post-war monopoly on such a powerful weapon could lead to nuclear catastrophe, Hall began passing key information about the bomb's construction to the Soviet Union. After the war, he met, fell in love with, and married Joan, a fellow student with whom he shared a passion for classical music and socialist causes, and the explosive secret of his espionage. The pair raised a family while living under a cloud of suspicion and years of FBI surveillance and intimidation. The film reveals the twists and turns of this real-life spy story and the couple's remarkable love and life together during more than 50 years of marriage...'

#Steve James#A Compassionate Spy#Oppenheimer#The Manhattan Project#Christopher Nolan#Leslie Groves#Cillian Murphy#Emily Blunt#Robert Downey Jr.#Matt Damon#Ted Hall

0 notes

Text

MAD MEN BOOK RECS

Happy pride/Don Draper’s fake birthday ❤️ Below the cut, I’ve listed info on my favorite Mad Men related books and a couple I haven’t read yet but I’m really looking forward to. Let me know if you check any of these out, or if you have any other recommendations! ❤️

Mad Men Carousel: The Complete Critical Companion by Matt Zoller Seitz

“Mad Men Carousel is an episode-by-episode guide to all seven seasons of AMC's Mad Men. This book collects TV and movie critic Matt Zoller Seitz’s celebrated Mad Men recaps—as featured on New York magazine's Vulture blog—for the first time, including never-before-published essays on the show’s first three seasons. Seitz’s writing digs deep into the show’s themes, performances, and filmmaking, examining complex and sometimes confounding aspects of the series. The complete series—all seven seasons and ninety-two episodes—is covered.

Each episode review also includes brief explanations of locations, events, consumer products, and scientific advancements that are important to the characters, such as P.J. Clarke’s restaurant and the old Penn Station; the inventions of the birth control pill, the Xerox machine, and the Apollo Lunar Module; the release of the Beatles’ Revolver and the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds; and all the wars, protests, assassinations, and murders that cast a bloody pall over a chaotic decade.

Mad Men Carousel is named after an iconic moment from the show’s first-season finale, “The Wheel,” wherein Don delivers an unforgettable pitch for a new slide projector that’s centered on the idea of nostalgia: “the pain from an old wound.” This book will soothe the most ardent Mad Men fan’s nostalgia for the show. New viewers, who will want to binge-watch their way through one of the most popular TV shows in recent memory, will discover a spoiler-friendly companion to one of the most multilayered and mercurial TV shows of all time.”

A classic episode-by-episode look at the series from reviewer Matt Zoller Seitz.

The Legacy of Mad Men — Cultural History, Intermediality and American Television (Edited by Karen McNally, Jane Marcellus, Teresa Forde, and Kirsty Fairclough)

“For seven seasons, viewers worldwide watched as ad man Don Draper moved from adultery to self-discovery, secretary Peggy Olson became a take-no-prisoners businesswoman, object-of-the-gaze Joan Holloway developed a feminist consciousness, executive Roger Sterling tripped on LSD, and smarmy Pete Campbell became a surprisingly nice guy. Mad Men defined a pivotal moment for television, earning an enduring place in the medium’s history.

This edited collection examines the enduringly popular television series as Mad Men still captivates audiences and scholars in its nuanced depiction of a complex decade. This is the first book to offer an analysis of Mad Men in its entirety, exploring the cyclical and episodic structure of the long form series and investigating issues of representation, power and social change. The collection establishes the show’s legacy in televisual terms, and brings it up to date through an examination of its cultural importance in the Trump era. Aimed at scholars and interested general readers, the book illustrates the ways in which Mad Men has become a cultural marker for reflecting upon contemporary television and politics.”

This is a really beautiful collection. It was published in 2019. It’s rather expensive. (I found a used copy for much cheaper.) If you can afford it, I really, really recommend buying it. There is a pdf floating around if you know where to look though. But like I said, it’s really amazing work and the women who curated it deserve high praise and compensation.

A few favorite essays of mine include “Don Draper and the Enduring Appeal of Antonioni’s La Notte” by Emily Hoffman, “Mad Men’s Mid-Century Modern Times” by Zak Roman, “Mad Men and the Staging of Literature via Ken Cosgrove and His Problems” by Aaron Shapiro, and “What Jungian Psychology Can Tell Us About Don Draper’s Unexpected Embrace of Leonard in Mad Men’s Finale” by Marisa Carroll.

Mad Men and Philosophy: Nothing Is as It Seems (Edited by William Irwin, James B. South, and Rod Carveth)

“With its swirling cigarette smoke, martini lunches, skinny ties, and tight pencil skirts, Mad Men is unquestionably one of the most stylish, sexy, and irresistible shows on television. But the series becomes even more absorbing once you dig deeper into its portrayal of the changing social and political mores of 1960s America and explore the philosophical complexities of its key characters and themes. From Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to John Kenneth Galbraith, Milton Friedman, and Ayn Rand, Mad Men and Philosophy brings the thinking of some of history's most powerful minds to bear on the world of Don Draper and the Sterling Cooper ad agency. You'll gain insights into a host of compelling Mad Men questions and issues, including happiness, freedom, authenticity, feminism, Don Draper's identity, and more.”

This collection was published just a month before the start of season 4, so it only concerns the first three seasons of the show. As such, it includes some assumptions that are proven false and a few strange misreadings that I’m sure would’ve been cleared up had they had the rest of the show at their disposal. But there are some great philosophical insights and analysis.

I haven’t yet read the whole collection, but my favorite essay of what I’ve read so far was “Pete, Peggy, Don, and the Dialectic of Remembering and Forgetting” by John Fritz.

The Fashion File: Advice, Tips, and Inspiration from the Costume Designer of Mad Men (by costume designer Janie Bryant)

From Joanie's Marilyn Monroe-esque pencil skirts to Betty's classic Grace Kelly cupcake dresses, the clothes worn by the characters of the phenomenal Mad Men have captivated fans everywhere. Now, women are trading in their khakis for couture and their pumas for pumps. Finally, it's hip to dress well again. Emmy-Award winning costume designer Janie Bryant offers readers a peek into the dressing room of Mad Men, revealing the design process behind the various characters' looks and showing every woman how to find her own leading lady style--whether it's vintage, modern, or bohemian. Bryant's book will peek into the dressing room of Mad Men and reveal the design process behind the various characters' looks. But it will also help women learn how fashion can help convey their personality. She will help them cultivate their style, including all the details that make a big difference. Bryant offers advice to ensure that a woman's clothes convey her personality. She covers everything from where to find incredible vintage clothing and accessories to how to pair those authentic pieces with modern shoes and jeans. Readers will learn how to find their perfect bra size, use color to convey a mood, and invest in the ten essentials every woman should own. And just so the ladies don't leave their men behind, there's even a section on making them look a little more Don Draper-dashing.

I recently ordered a used copy of this book and haven’t yet received it, but I’m very much looking forward to it. Like Mad Men and Philosophy listed above, it was published between season 3 and 4, so unfortunately does not cover the whole show. It sounds like it might just cover the women’s costume design, though I’m not sure. Janie Bryant is such a meticulous, genius costume designer that I can’t wait to read it. Relatedly, you should follow her incredible costume design instagram where she posts lots of her work from Mad Men and other shows with fascinating insight into her process.

The Universe is Indifferent: Theology, Philosophy, and Mad Men (Edited by Ann W. Duncan and Jacob L. Goodson)