#Junior Johnson & Associates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Terry Labonte

#Terry Labonte#NASCAR#Hagan Racing#Junior Johnson & Associates#Precision Products Racing#Hendrick Motorsports#Joe Gibbs Racing#Hall of Fame Racing#colewicki#NASCAR Careers

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My Favorite Neil Bonnett Quote.

#Neil Bonnett#NASCAR#Winston Cup#The Alabama Gang#Hueytown#Alabama#Wood Brothers#RahMoc Enterprises#Junior Johnson & Associates#Racing History#Stock Car Racing#Quotes

1 note

·

View note

Text

NASCAR Numerology: How NASCAR's Current Teams Got Their Number: Part Two.

Hello all, this is part two of my little mini-series on how and why NASCAR teams have their current numbers. Last time we did Trackhouse, Team Penske, and I tacked on Wood Brothers because it was topic. Today we're continuing down the list - we covered the teams with the #1 and the #2 yesterday, now to talk about the team with the #3.

Quite possibly the most iconic number in all of NASCAR, when someone says the #3, NASCAR fans always think of Dale Earnhardt in the black intimidator GM Goodwrench Chevrolet...but that's not quite how the #3 car started.

In fact, it started in the early 70s with team owner Richard Childress himself, who would go part time with numbers like #13, #96, and #98 in those early starts. In 1976, however, Richard Childress would go full time in his self-owned car, and the number he chose was the #3.

Why? Well, Richard said it was in tribute to Junior Johnson, who ran the #3 49 times from 1961 and 1964, and won 9 races with it. Junior Johnson owned the #11 and the #27 for his own team, so the #3 was the most notable Junior Johnson available.

Thus, in 1976, the #3 car began.

In mid-1981, Richard Childress was considering retirement. At the same time, Dale Earnhardt in the #2 Osterlund Racing car saw his team get sold to JD Stacy, and thus the partnership that won the 1980 championship collapsed just half a season later.

Dale Earnhardt took over RCR's #3 and brought sponsor Wrangler with him. The #3 wasn't quite to Dale's level though, so for 1982 and 1983, Dale switched to Ford and ran the #15 Bud Moore Engineering car. Ricky Rudd took over the #3 for two years and managed to get RCR's first and second wins, at Riverside and Martinsville.

This was the same number of wins that Dale got at Bud Moore Engineering in the #15, thus, Dale felt it was time to return to RCR and the #3.

Thus, the most famous partnership in NASCAR began, with Wrangler sponsorship through 1987, and then in 1988, the car gained the famous black, silver, white, and red GM Goodwrench sponsorship. It gained a thousand names: the intimidator, the man in black, Darth Vader...this was the most famous car in stock car racing.

And in the 2001 Daytona 500, as the DEI #15 and #8 - numbered after Dale's Bud Moore car and Dale's Busch series car - finished one-two in NASCAR's biggest race, Dale Earnhardt was killed in a turn four wall impact.

A legend had died.

Kevin Harvick was drafted in to replace him, but the paint scheme was changed, and RCR changed the number immediately. The #13 and the #23 were available, but RCR did not want to burden Harvick with a number associated with the #3 at all, thus, RCR chose the #29 instead.

This meant that, for a time, RCR had the #29, the #30, and the #31, a set of consecutive numbers.

In 2014, however, Kevin Harvick moved to SHR (more on that in a moment) and Austin Dillon took over his car...and it was renumbered the #3 again.

Why? Well, Richard Childress once famously announced that the #3 would only come back in the hands of an Earnhardt or a Childress, and Austin Dillon was Richard's grandson via his daughter. Needless to say, this has been controversial.

Lots of people feel that Austin Dillon isn't there on merit, instead he's there by nepotism. They feel that after Dale's death, the #3 should've been retired outright.

Well, they didn't do that and the #3 is back.

And RCR's second car...well, it's not the #30 or the #31 anymore, nor the #07, the #27, the #33, or any other number that RCR has run in the past.

Rather it is the #8...that number Dale Earnhardt ran in Busch and later Dale Earnhardt Jr. made famous at DEI. Why the #8? Well, it was used by Ralph Earnhardt (Dale's father) in his racing days. So how the heck did RCR end up with such an intimately Earnhardt number?

Well, it should be noted that Richard Childress and Dale Earnhardt were close friends.

Furthermore, when RCR brought back the #8, it was initially for Daniel Hemric, who is from Kannapolis, North Carolina - the same town that the Earnhardts are from.

That doesn't quite explain why they kept the #8 for Tyler Reddick and now Kyle Busch, but that's why they brought it back.

Like I said, Earnhardt nostalgia.

Now, onto SHR, who run the #4, the #10, the #14, and the #41.

When Tony Stewart bought into Haas CNC Racing (who had been running numbers like #60, #0, #66, and #70) they completely overhauled the numbering scheme.

Tony Stewart - who had originally come from an Indy Racing League background - wanted the #14 for himself, as that had been the number of his racing hero, AJ Foyt. Stewart succeeded, and he'd pass that number down to Clint Bowyer and now Chase Briscoe, the current driver.

Meanwhile, he wanted the #4 for his teammate, as that had been Tony's karting number. Unfortunately, Morgan-McClure Motorsports still owned the #4 at this time, so Tony's 2009 teammate instead had to settle for running the #39 at the time. It should be noted that Newman had run the #39 Dodge in the second-tier Busch series before at this point, so he did have an association with this number.

Once Ryan Newman left the team at the end of 2013, the team brought in Kevin Harvick and his Anheuser-Busch sponsorship (initially with Budweiser, later with Busch Light) for 2014, and finally managed to change the number to #4. They were rewarded with an immediate championship in 2014.

The #10 car came next, with SHR bringing Danica Patrick over from the world of Indycar. They initially wanted Danica's Indycar number with the #7, but that was unavailable, so they went with the #10 instead, with was one of Danica's karting numbers.

When Danica retired at the end of the 2017 season, they kept the #10 for Aric Almirola (and now Noah Gragson for 2024).

Presumably they felt that since 4+10=14, the number suited their numbering scheme.

Also suiting the numbering scheme is the #41, which is #41 backwards. Despite being Tony's number inverted, the #41 has traditionally been seen as Gene Haas' car in the Stewart-Haas pairing, with Gene bringing in Tony's rival Kurt Busch in for the 2014 season (announcing this while Tony was out injured, no less).

Daniel Suárez would drive the car in 2019, and then Cole Custer (the son of Joe Custer, who manages Gene Haas' racing operations) would drive it from 2020 to 2022.

Tony then managed to get Ryan Preece - a more grassroots kind of driver, the kind of driver Tony likes - in the car for 2023 and 2024, with results staying about the same.

Gene will get the last laugh though, because even as Stewart-Haas Racing is closing its doors, Gene Haas will keep the #41 as Haas Factory Racing, and Cole Custer will return to the NASCAR Cup Series for 2025.

Guess the #41 really was Gene's car all along, huh?

Anyway, that's six cars down today. The next car on the list would be the #5...Hendrick is a four-car team with a ton of history, and they've played a lot of number roulette over the years, so we'll handle them tomorrow. Hendrick, Roush, and maybe Spire to knock out the #5, the #6, and the #7. We did #8 here, #9 is with Hendrick, and the #10 we also covered here, so...it looks like we'll pick up with Joe Gibbs Racing and the #11 on Thursday.

Sounds good?

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

BD - winners where are they now (incomplete)

I think someone requested this somewhere

Most females and recent males because there are just too many to do rn

At companies:

Miriam Gittens (s2013): Gibney Company

Alyssa Allen (s2014): Ballets Jazz Montreal

Brianne Sellars (s2014): Dallas Black Dance Theatre

Ashley Green (s2015): Alvin Ailey American dance Theater

Payton Johnson (j2012, t2015, s2017): L.A. Dance Project

Vivian Ruiz (s2019): Ballet BC

Kelis Robinson (t2018, s2020): The Batsheva Dance Company; The Juilliard School

Kiarra Waidelich (m2016, j2018, t2020): Royal Flux Company

Quinn Starner (t2017): New York City Ballet Corps de Ballet

Emma Sutherland (j2014, t2016): MashUp Contemporary Dance Co.

Sarah Pippin (t2011): Ballet BC

Timmy Blankenship (s2017): Sydney Dance Company; choreographer

Brady Farrar (m2014, j2017, t2021): ABT Junior Company

Easton Magliarditi (t2020): Royal Flux Company

Graham Feeny (t2015): Artistic associate at Gibney Company

Logan Hernandez (t2015): Göteborgs Operans Danskompani

Zenon Zubyk (t2013): Nederlands Dans Theater

Jonathan Wade (j2011, s2016): Rambert Dance Company

Wyeth Walker (s2017): Rubberband Dance Company

Faculty/teacher/choreography:

Lucy Vallely (t2015, s2018): Broadway Dance Center, freelance choreographer

Jayci Kalb ( j2011, t2014, s2016): The Dance Centre; Radio City Clara 2010

Taylor Sieve (s2016): Jump Dance Convention

Jenna Johnson (s2012): DWTS pro, 24 Seven Dance Convention

Jazzmin James (t2012, s2015): faculty several intensives

Jaycee Wilkins (j2015): Club Dance Studio

Sophia Lucia (j2014): Dancelab OC

Brynn Rumfallo (m2014): Strive Dance Workshop (own project)

Talia Seitel (m2012): Project 21 (part-time)

Lex Ishimoto (t2014, s2016): Jump Dance Convention

at University/college:

Ellie Wagner (s2019): Ohio State University Dance Team

Ella Horan (s2021): USC Kaufman

Kayla Mak (m2014, s2021): The Juilliard School; Radio City Clara 2014, 2015

Brianna Keingatti (s2022): The Juilliard School

Julia Lowe (s2023): USC Kaufman

Ava Wagner (j2018): University of Minnesota Dance Team

Avery Gay (m2015, j2017): University of Arizona School of Dance

Leara Stanley (m2011): Duke University

Sam Fine (s2023): USC Kaufman; Young Arts 2022

Seth Gibson: The Juilliard School

Alex Shulman (s2022): New York University Tisch Dance

Joziah German (m2014, t2018, s2020): The Juilliard School

Joey Gertin (t2018): The Juilliard School

Professional dancer/choreographer:

Simrin Player (t2014, s2017): The Voice, Missy Elliot, Justin Bieber, RBD

Jaxon Williard (s2021): Rihanna, Madonna, Lil Nas X

D'Angelo Castro (j2012, t2016, s2019): DWTS troupe

Findlay Mcconnell (t2017, s2019): Tate McRace

Christian Smith (s2018): Tate McRae, NBC's Saved by the Bell

Keanu Uchida (s2014): Dancer the Musical; also a big advocate for protecting dancers and calling out inappropriate behaviour

Eric Schloesser (s2014): Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Dua Lipa, Billie Eilish, J Balvin; choreographer, creative director, designer; Dana Foglia Dance Company

Other/a combo of things:

Bianca Melchior (s2011): actor, dancer, singer; Nick Jonas, Alessia Cara, own music; faculty at On The Floor dance competition

Tate McRae (m2013, j2015, t2018): singer/songwriter

Bostyn Brown (j2016, t2019): Professional assistant at DanceOne

Megan Goldstein (t2017); dancer, photographer

Christina Ricucci (t2013): actor, musician, dancer

Bella Klassen (j2017): The Space, vlogger

Kalani Hilliker (j2013): influencer, teaching at several places (Danceplex, MBA)

Elliana Walmsley (m2018): influencer, DWTS Junior, Radio City Clara 2019

Diana Pombo (m2016): singer/songwriter, dancer, actor; Young Arts voice 2023+2024

Morgan Higgins (t2016, s2018): dancer, aerialist

Zelig Williams (s2013):dancer/actor: MJ the Musical, Hamilton

Daniel Gaymon (s2011): dancer/actor; Broadway (Cats, The Lion King); Hamilton national tour, La La Land

Ricky Ubeda (t2011, s2012): choreographer, actor; Steven Spielberg's West Side Story

Michael Hall (s2015): Saturday Night Fever the Musical, tv dancer in Cairo, Egypt; teacher

Julian Elia (t2014): Steven Spielberg's Westside Story, working on the development of a new Broadway musical

Sage Rosen (t2016): influencer; DWTS Junior

Ryan Maw (j2015, t2017): choreographer, dancer, actor: High School Musical: The Musical - The Series

Holden Maples (j2016, t2019): dancer, teacher, choreographer

Competing/not graduated honorable mentions:

Cameron Voorhees (m2018, j2021, t2023): Evolve Dance Complex; starting career as a teacher/choreographer

Crystal Huang (m2019, j2021, t2023): The Rock Center for Dance, Bayer Ballet Academy; Prix De Lausanne 2024, Young Arts 2024, Radio City Clara 2021

Hailey Bills (m2017, t2022): Center Stage Performing Arts Studio, DWTS Junior

Brightyn Brems (m2017): DWTS Junior

Avery Hall (t2022): Danceology; Young Arts 2023

Savannah Kristich (t2021): The Rock Center For Dance; Twyla Now

Savannah Manzel (m2020): Larkin Dance Studio, Radio City Clara 2023

Kya Massimino (m2021): Radio City Clara 2023

Ian Stegeman (m2019, j2021, t2023): Woodbury Dance Center, Young Arts 2024

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

If You Can’t Do the Time, Don’t Do the Crime

Stock car racing was founded by a group of rag tag criminals. In the 1940’s, one of the ways people made money in the U.S, was by making, delivering, and selling illegal moonshine. In order to do this without getting arrested, these whiskey sellers built cars that could go faster than cop cars, so they could outrun the police. Then they took their fast cars and began racing each other. Then a man named Bill France organized a stock car race in 1948 on the beach of Daytona. He and a group of people created a racing series and called it the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing. This organization has been around for over 70 years, and to this day, drivers that compete in this sport still find themselves on the wrong end of the law. Today, we’re going to look at the times NASCAR drivers got arrested. Also, I’m putting up a disclaimer. I’ll be going over some sensitive topics, read at your own risk.

First up, we have Kurt Busch. He ended up missing the first few races of the 2015 season, due to allegations made by his ex-girlfriend. She claimed that Kurt Busch abused her. This is not the first time Kurt Busch got involved in controversy. His career was littered with crazy things happening to him. Ultimately, Kurt was found innocent and was cleared of any wrongdoing. I would like to point out that at this point in the season, his younger brother Kyle Busch had just badly injured himself after a crash in the season opening Xfinity race at Daytona. Both of Kyle’s legs were broken. Kurt had to deal with being accused of a crime he didn’t commit, while also having to deal with a blood relative going through a really painful injury.

Next up we have the last American hero, Junior Johnson. Even after NASCAR was founded, he was still selling illegal whiskey. In 1956, a police officer caught him with a ludicrous amount of illegal moonshine. Junior Johnson then smacked the police officer in the head with a shovel. He then found himself surrounded by 15 cops. When Junior Johnson tried to make a run for it and escape, he failed miserably. He ended up getting caught in a barbed wire fence. Those things are painful, and I usually try to keep my distance from fences like that. I hope the pointy fence didn’t pierce Junior Johnson’s male part, that would have been bad.

In 2022, 18-year-old Arca driver Daniel Dye violated the bro code. He punched a classmate, in the crotch. I’ve heard of kicks being sent there but punches? In more ways than one, that is a low blow. And this punch did some serious damage. Here is what happened to the kid that got punched, I kid you not. He ruptured his testicle and bruised his scrotum. I cannot believe I am actually typing this right now. Teenagers, am I right? They tend to get a bit wild.

Now we go to 2007. This was the year Michael Waltrip Racing was formed. Team owner Michael Waltrip got into trouble for reckless driving. He crashed into a telephone pole, and then fell asleep behind the wheel. When he woke up, he then got out of his car, and walked a mile back to his house, without reporting the accident. To this day, it is unknown if he was under the influence of alcohol or not. Early in the season, he had already gotten in trouble during the season opening Daytona duels. NASCAR ended up finding jet fuel in the gas take of his racecar. First freaking jet fuel of all things, and now this? Mikey, buddy, take it easy, we’ve already got enough people in this sport going crazy. Don’t encourage them.

And now we come to the fifth and final driver. This time, believe it or not, it isn’t Mark Martin. This time, Mark decided to stay at home and be a good little boy. Good job Mark, have a lollipop. The same cannot be said about former truck series driver Rick Crawford. While Crawford wasn’t a top driver, he was also nowhere near the bottom of the list. His career was pretty respectable. He won 5 races, got 75 top 5’s, and 160 top 10’s. Then in 2018, he was having an online chat with a complete stranger. This stranger was offering to let Rick Crawford have sexual intercourse with his 12-year-old daughter. Crawford was willing to pay 50 to 75 dollars so he could have sex with her. It turns out, this whole thing was a sting operation to catch Rick Crawford red handed. After this, that sick pedophile was put in prison, and he is still there to this day. When he gets released from prison, he could theoretically turn his life around and become a better person, but I don’t have very high hopes. Not many people can redeem themselves after something as bad as this.

Well, that’s it for today. What are some interesting stories you have to share about drivers getting arrested? Let me know in the comments, and I might make part 2.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

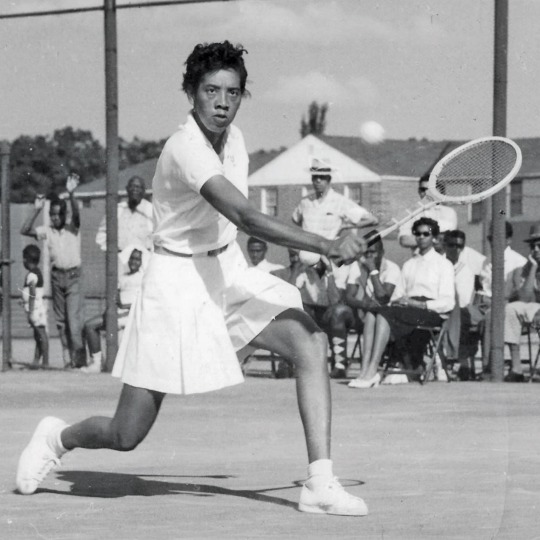

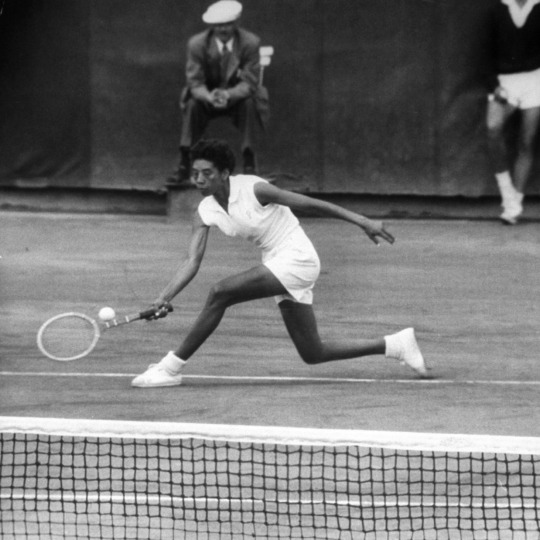

Dr. Hubert Arthur Eaton (December 2, 1916 - September 4, 1991) was a physician, civil rights activist, and tennis player in North Carolina.

The son of a Winston-Salem physician, he attended Johnson C. Smith University on a tennis scholarship after winning the 1933 national junior championship of the American Tennis Association, the African American counterpart to the United States Tennis Association. He would go on to win the ATA national doubles championship and served as the coach and mentor of Althea Gibson, the first African American Wimbledon champion. He played in the 1954 US Championships, losing his match to top seed Tony Trabert.

He attended the University of Michigan Medical School and established a practice in Wilmington, North Carolina, where he was a distinguished physician and noted civil rights activist, fighting for access to recreational facilities, the desegregation of public schools, and, most notably, the fight for access to public hospital facilities for African American physicians.

In 1956, he was a plaintiff in a lawsuit against a public hospital that, by policy, only granted hospital privileges to white physicians. After he prevailed in court, he remarked “If you don’t know what to do, go to court; that is the only way we know of in Wilmington, North Carolina.” He worked to desegregate patient wards, stating that the African American community “[did not] want the partially integrated hospital where everything will be integrated except patients”.

In 1964, he was charged with murder. A trial was held, but the judge ordered a directed verdict of not guilty because of insufficient evidence before the jury began deliberations. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's Black History Month illustration is of Althea Gibson. She became the first Black athlete to cross the color line of international tennis and golf. (She has a TON of records, so here it goes!)

Gibson was born in 1927 on a cotton farm in South Carolina, but her family moved to Harlem in 1930. While growing up in NYC, she played paddle tennis under the supervision of the New York Police Athletic League. She became so good at paddle tennis that by the age of twelve, she won the NYC women’s paddle tennis championship.

In 1940, a group of Gibson’s neighbors put money together to pay for her junior membership at the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club in Harlem. A year later, she won her first tournament, the American Tennis Association’s NY State Championship, founded by Black tennis players. She won the ATA national championship in 1944 & 1945. In 1947, she won the ATA’s women’s singles championship, which she continued to win for 10 consecutive years.

Her success drew the attention of Dr. Walter Johnson, a Black physician from Virginia who was also an avid tennis player. He mentored her and helped her enter into competitions with the US Tennis Association (USTA). In 1949, she became the first Black woman and second Black athlete to play in the USTA’s National Indoor Championship. After that, she received a full athletic scholarship at Florida A&M.

In 1950, Gibson became the first Black to compete in the US Open at Forest Hills in Queens, NY. In 1956, she became the first African American to win the French Open. In 1957, she won Wimbledon, and received the trophy personally from Queen Elizabeth. She won the doubles championship as well and when she returned to NYC, she became the second athlete (after Jesse Owens) to receive a ticker tape parade.

In late 1958, after winning 56 national and international singles and doubles titles including 11 Grand Slam championships, she retired from amateur tennis at the age of 31. In 1964, at the age of 37, she became the first Black woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour. Her best tournament finish was a tie for second place at the 1970 Buick Open.

Overall, Althea Gibson is considered to be one of the greatest tennis players in history and paved the way for players like Venus and Serena Williams.

I’ll be back tomorrow with another illustration and story!

#Althea Gibson#black history month 2023#black history month#black history 365#artists on tumblr#illustrators on tumblr#black women art#kidlitart

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Loving Memory Of the Fallen

This memorial is dedicated to the courage and honor of our fallen teammates. Their dedication and sacrifice will never be forgotten.

Here are the names of our fallen. Each name is accompanied by a page dedicated to honoring and remembering them, where photos or stories can be shared.

* Indicates those who are the Original 43

January

Casey Casavant (Rooster)*

Steve Gernet (G-Man)*

Ron Johnson (Cat Daddy)*

Arthur Laguna (Art)*

Shane Stansfield (War Baby)*

Jerome McCauley (Jerry)*

Matt Fineran*

Walter Fisher*

William Reid Ray (Billy)

Sean Hawkins (Hawk)

James Patrick Flynn (Seven)

Dean Leon Silva (Windex)

Christopher P. Gaffney

February

Nicholas W. Leotti*

Michael McInnis (Mac)

Jim Grey (Mammal)

Lance Warren (#1 Dad)

Cory Gene Wainscott

Lee Eric Martin (Biggin)

Keith Jorgensen (Snake Doctor)

Tommy Lopez

Jeffrey Keith Reynolds (Festus)

Richard Garcia (Witch Doctor)

Charles Hughes (Hugo)

Glen Wenzel

March

Wesley John Kealoha Batlona (Wes)*

Stephen Scotten Helvenston (Scott)*

Mike Teague (Iron Mike)*

Jerko Gerald Zovko (Jerry)*

Bruce T Durr (Bee)*

James Cantrell (Tracker)*

Stuart Rice

William Posch

Michael Tharp

April

Peter Goodfellow (Dingo)*

Robert Gore (Jason)*

Curtis Hundley (Sparky)*

Steven McGovern*

Jason Obert*

David Patterson (Mike)*

Luke Petrik (Black Diamond)*

Eric Smith*

Patrick Waterbury (Stazi)

Craig Fuller (Firecracker)*

Norman Spruill (Old School)

Abraham Bronn

Scott Sandefer (Sandman)

May

Thomas Jaichner (Bama)*

Thomas Capel (Grundle)

Brandon Teague

Steven Powell (Junior)

June

Richard Bruce (Kato)*

Krzysztof Kaskos*

Jarrod Little*

Christopher Neidrich*

Artur Zukowski*

David Olinger (Dave-O)

Joshua Hernandez (Pedro)*

Corey Meile (Olaf)

William Larson (Gunz)

July

William Hinchman (Sonny)*

Roland Tressler (Johny Quest)*

Michael Sacks (Max)*

Cory Gray

Antouine Castenada (Lips)

Sean Barton (Taxi)

Duane Xanders

Bart Baker

August

Charles Geisler (Bullfrog)

Philip VanDyke

William Woods (Brian)*

Joseph Bixler (Bix)

Michael Oyer

Roger Abshire (Nitro)

Christopher Hartsock

Mike Hawley (Mike)

September

David Shepherd (Chief)*

Stephen Sullivan*

Peter Tocci (Bear)*

Kenneth Webb (2B)*

Jack McCracken (Stagger)

Atom Ziniewicz

Carlos Guerrero (Tony)

Alan Nowak

Robert Schierenberg

Chad Burke

October

Rod Richardson (K2)*

Thomas Capel (Grundle)

Brandon Teague

Steven Powell (Junior)

Eric Chapa

Nickolaus Dillon

Jordan Pyle

November

David Randolph*

Noel English*

Loren Hammer (Butch)*

Melin Rowe*

David Laconte

Thomas Mitchell

Christopher Coene (Superfly)

Steven White (Blanco)

Raymond Tanner

December

Dane Paresi*

Scott Roberson*

Jeremy Wise*

Scott Brachmann (Mongo)

Ken Bell (Thumper)

Christopher Shellhamer

James Parker Jr. (Doc)

Sean Bowles (Rock Ape)

Terrance Cullinan

Jason Terrell (Turbo)

Col George Smith (Doc Smith)

Willard Baber (Buddy)

Blackwater Memorial Alumni Association is a registered 501 (c)3 Non-Profit Organization

© 2023 by Blackwater Memorial Alumni Association

EIN # 83-0860644

0 notes

Photo

Getty Images It’s endearing to witness someone’s style evolve as they age. It’s why many fashion lovers believe the youth-obsessed, youth-dependent fashion world should platform mature talent more often. Because as you age, your taste is increasingly defined. You wear clothes differently, with credibility, given you’ve had them forever, and every imperfection bespeaks your body’s contours. Your dress, one hopes, not only gains sophistication but stays ever-traceable to its roots. Of all that makes André 3000 special, that’s what I’ve found particularly remarkable lately since not all rappers carry the aesthetic that was once their signature well into adulthood. Where Busta Rhymes was once the unflinchingly offbeat dresser misunderstood by many, he now favors the conventional codes of hip-hop showiness. Some other artists of his era, too, have become faltering logomaniacs. And Snoop Dogg, whose Rastafarian-inspired locs mark the most, if only notable shift in his appearance, can hardly be seen in more than a bomber jacket, a matching set, requisite jewelry, and the occasional bucket hat. Photo Credit: M. Caulfield/WireImage for VH-1 Channel Right now it appears that there is a fashionable decline of the generals. But even a veteran fashion reporter immersed in the world of clothes has confessed to me that hers are much, much less a priority now than when she was working in the industry. Fashion as you age can indeed become the least important component of life. Not so for André! He remains a trailblazer in matters of the cloth, which throughout his career has covered his flawlessly pressed and permed hair in the form of a church lady-inspired headwrap, dandified his many silhouettes through suiting, been seer suckered for overalls worn with diva-like sunglasses and a ribbed beanie. His GQ Men of The Year photoshoot in that outfit is what many of us associate with what we’ve referred to as the artist’s “flute era.” His 2023 debut solo and now Grammy-nominated instrumental album New Blue Sun would make apparent his artistic expansion as a flutist, symbolizing his prevailing stylistic prowess despite puzzlements over his sonic shift. But that is the stuff that has made André 3000 the nonpareil figure we’ve come to adore. Patrick Johnson, a scholar and Sonoma State professor of American multicultural studies, sees the rapper’s style choices as metaphors that help narrate a bigger composition. “It’s the glasses; it’s the little notes he’s hitting in his fashion that says, ‘Okay, I’m thinking about these things differently, I’m flipping it,’” Johnson shared. But the reason he’s so relatable, so fly to us, is put plainly by Johnson. “André never feels outside of what other brothers are doing.” He isn’t entirely separate from or, say, weirdly above his peers who were “wearing jerseys and pink, furry Kangos. He was very much in relationship with what other Black men were doing,” Johnson continued. Photo Credit: SGranitz/WireImage André 3000 has influenced rap eccentrics his junior whose idiosyncratic sensibility is seen in their sound and clothes: California’s Tyler, the Creator, Cavalier from Brooklyn, and EarthGang, the Atlanta group for which Spelman’s curator in residence Karen Lowe brings OutKast to mind. Knowing André is knowing he comprised half of the classic rap duo OutKast, and the mention of their infamous video, “Hey Ya!,” will summon the image of him clad in a St. Patty’s green button-up, wide, white suspenders affixed to tartan trousers, and a green and black peppermint ascot, vigorously singing and bobbing his head with a shoulder-length bob. Those are the accouterments of an outstandingly dressed Black man, a dandy, to be sure, but that gives way to André centering himself in the video–self-replicating and standing in as seemingly minor characters. And in effect displaying his creative range. He’s a Black man who isn’t afraid to play with ideas, a quality Johnson describes as instructive. “Think about the Benjamin Bixby stuff. At some point, “André embraced prep and Americana through a distinctly Southern perspective,” he explains. Here Johnson also mentions Benjamin Bixby, the now-defunct clothing line by the artist that centered around Black dandyism. Photo Credit: Julia Beverly/Getty Images Lowe agrees. Three years ago, she spearheaded an open-air digital exhibition titled “The South Got Something to Say,” taken from the rapper’s 1995 Source Awards speech, where he called out the ceremony and its dismissal of the South’s contributions to the genre when we were shaping it in real-time. But the region, however influential and formative, hasn’t always been so free for Black men with expressive style. The curator mentions that the same can be said about Black culture at large. André 3000’s narrative is emancipatory; he represents a rare liberty. As a Black Southern man, he personifies a freedom that permits individuality without always being misunderstood. Lowe, who, like André 3000, is an Atlanta native, speaks to his free nature in “how he moves” and “not being defined by stereotypes and expectations.” To her, he appears to be mentally free. At times, he outright defies culturally imposed notions, like when he wears ultra-preppy clothing, he one-ups their assumed originators. Photo Credit: Barry Brecheisen/WireImage Other times, he plays into them as one of hip hop’s significant titans nonetheless. But he isn’t bound to either: in music or fashion. His references can be so rich they go over your head, such as his wearing a white wig in Outkast’s “Prototype” video, referencing P-Funk, a doo-wop band out of New Jersey. (A white wig he wore during one of his international concerts in 2014 is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Musical Crossroads Gallery.) Lessons aplenty can be learned from the explorer, the inventor, the experimenter, and the man that is André 3000—among them that a childlike enthusiasm for clothing can prevent one’s style from going stale, that our wardrobes can effectively be toy boxes. His strange swagger shows how the hodgepodge of influences that often make a terrific outfit should be honest. And that the most genuinely iconic dressers in American history stayed curious. Who else has done that while keeping as suave as the best-dressed men in our families? Source link

0 notes

Photo

Getty Images It’s endearing to witness someone’s style evolve as they age. It’s why many fashion lovers believe the youth-obsessed, youth-dependent fashion world should platform mature talent more often. Because as you age, your taste is increasingly defined. You wear clothes differently, with credibility, given you’ve had them forever, and every imperfection bespeaks your body’s contours. Your dress, one hopes, not only gains sophistication but stays ever-traceable to its roots. Of all that makes André 3000 special, that’s what I’ve found particularly remarkable lately since not all rappers carry the aesthetic that was once their signature well into adulthood. Where Busta Rhymes was once the unflinchingly offbeat dresser misunderstood by many, he now favors the conventional codes of hip-hop showiness. Some other artists of his era, too, have become faltering logomaniacs. And Snoop Dogg, whose Rastafarian-inspired locs mark the most, if only notable shift in his appearance, can hardly be seen in more than a bomber jacket, a matching set, requisite jewelry, and the occasional bucket hat. Photo Credit: M. Caulfield/WireImage for VH-1 Channel Right now it appears that there is a fashionable decline of the generals. But even a veteran fashion reporter immersed in the world of clothes has confessed to me that hers are much, much less a priority now than when she was working in the industry. Fashion as you age can indeed become the least important component of life. Not so for André! He remains a trailblazer in matters of the cloth, which throughout his career has covered his flawlessly pressed and permed hair in the form of a church lady-inspired headwrap, dandified his many silhouettes through suiting, been seer suckered for overalls worn with diva-like sunglasses and a ribbed beanie. His GQ Men of The Year photoshoot in that outfit is what many of us associate with what we’ve referred to as the artist’s “flute era.” His 2023 debut solo and now Grammy-nominated instrumental album New Blue Sun would make apparent his artistic expansion as a flutist, symbolizing his prevailing stylistic prowess despite puzzlements over his sonic shift. But that is the stuff that has made André 3000 the nonpareil figure we’ve come to adore. Patrick Johnson, a scholar and Sonoma State professor of American multicultural studies, sees the rapper’s style choices as metaphors that help narrate a bigger composition. “It’s the glasses; it’s the little notes he’s hitting in his fashion that says, ‘Okay, I’m thinking about these things differently, I’m flipping it,’” Johnson shared. But the reason he’s so relatable, so fly to us, is put plainly by Johnson. “André never feels outside of what other brothers are doing.” He isn’t entirely separate from or, say, weirdly above his peers who were “wearing jerseys and pink, furry Kangos. He was very much in relationship with what other Black men were doing,” Johnson continued. Photo Credit: SGranitz/WireImage André 3000 has influenced rap eccentrics his junior whose idiosyncratic sensibility is seen in their sound and clothes: California’s Tyler, the Creator, Cavalier from Brooklyn, and EarthGang, the Atlanta group for which Spelman’s curator in residence Karen Lowe brings OutKast to mind. Knowing André is knowing he comprised half of the classic rap duo OutKast, and the mention of their infamous video, “Hey Ya!,” will summon the image of him clad in a St. Patty’s green button-up, wide, white suspenders affixed to tartan trousers, and a green and black peppermint ascot, vigorously singing and bobbing his head with a shoulder-length bob. Those are the accouterments of an outstandingly dressed Black man, a dandy, to be sure, but that gives way to André centering himself in the video–self-replicating and standing in as seemingly minor characters. And in effect displaying his creative range. He’s a Black man who isn’t afraid to play with ideas, a quality Johnson describes as instructive. “Think about the Benjamin Bixby stuff. At some point, “André embraced prep and Americana through a distinctly Southern perspective,” he explains. Here Johnson also mentions Benjamin Bixby, the now-defunct clothing line by the artist that centered around Black dandyism. Photo Credit: Julia Beverly/Getty Images Lowe agrees. Three years ago, she spearheaded an open-air digital exhibition titled “The South Got Something to Say,” taken from the rapper’s 1995 Source Awards speech, where he called out the ceremony and its dismissal of the South’s contributions to the genre when we were shaping it in real-time. But the region, however influential and formative, hasn’t always been so free for Black men with expressive style. The curator mentions that the same can be said about Black culture at large. André 3000’s narrative is emancipatory; he represents a rare liberty. As a Black Southern man, he personifies a freedom that permits individuality without always being misunderstood. Lowe, who, like André 3000, is an Atlanta native, speaks to his free nature in “how he moves” and “not being defined by stereotypes and expectations.” To her, he appears to be mentally free. At times, he outright defies culturally imposed notions, like when he wears ultra-preppy clothing, he one-ups their assumed originators. Photo Credit: Barry Brecheisen/WireImage Other times, he plays into them as one of hip hop’s significant titans nonetheless. But he isn’t bound to either: in music or fashion. His references can be so rich they go over your head, such as his wearing a white wig in Outkast’s “Prototype” video, referencing P-Funk, a doo-wop band out of New Jersey. (A white wig he wore during one of his international concerts in 2014 is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Musical Crossroads Gallery.) Lessons aplenty can be learned from the explorer, the inventor, the experimenter, and the man that is André 3000—among them that a childlike enthusiasm for clothing can prevent one’s style from going stale, that our wardrobes can effectively be toy boxes. His strange swagger shows how the hodgepodge of influences that often make a terrific outfit should be honest. And that the most genuinely iconic dressers in American history stayed curious. Who else has done that while keeping as suave as the best-dressed men in our families? Source link

0 notes

Photo

Getty Images It’s endearing to witness someone’s style evolve as they age. It’s why many fashion lovers believe the youth-obsessed, youth-dependent fashion world should platform mature talent more often. Because as you age, your taste is increasingly defined. You wear clothes differently, with credibility, given you’ve had them forever, and every imperfection bespeaks your body’s contours. Your dress, one hopes, not only gains sophistication but stays ever-traceable to its roots. Of all that makes André 3000 special, that’s what I’ve found particularly remarkable lately since not all rappers carry the aesthetic that was once their signature well into adulthood. Where Busta Rhymes was once the unflinchingly offbeat dresser misunderstood by many, he now favors the conventional codes of hip-hop showiness. Some other artists of his era, too, have become faltering logomaniacs. And Snoop Dogg, whose Rastafarian-inspired locs mark the most, if only notable shift in his appearance, can hardly be seen in more than a bomber jacket, a matching set, requisite jewelry, and the occasional bucket hat. Photo Credit: M. Caulfield/WireImage for VH-1 Channel Right now it appears that there is a fashionable decline of the generals. But even a veteran fashion reporter immersed in the world of clothes has confessed to me that hers are much, much less a priority now than when she was working in the industry. Fashion as you age can indeed become the least important component of life. Not so for André! He remains a trailblazer in matters of the cloth, which throughout his career has covered his flawlessly pressed and permed hair in the form of a church lady-inspired headwrap, dandified his many silhouettes through suiting, been seer suckered for overalls worn with diva-like sunglasses and a ribbed beanie. His GQ Men of The Year photoshoot in that outfit is what many of us associate with what we’ve referred to as the artist’s “flute era.” His 2023 debut solo and now Grammy-nominated instrumental album New Blue Sun would make apparent his artistic expansion as a flutist, symbolizing his prevailing stylistic prowess despite puzzlements over his sonic shift. But that is the stuff that has made André 3000 the nonpareil figure we’ve come to adore. Patrick Johnson, a scholar and Sonoma State professor of American multicultural studies, sees the rapper’s style choices as metaphors that help narrate a bigger composition. “It’s the glasses; it’s the little notes he’s hitting in his fashion that says, ‘Okay, I’m thinking about these things differently, I’m flipping it,’” Johnson shared. But the reason he’s so relatable, so fly to us, is put plainly by Johnson. “André never feels outside of what other brothers are doing.” He isn’t entirely separate from or, say, weirdly above his peers who were “wearing jerseys and pink, furry Kangos. He was very much in relationship with what other Black men were doing,” Johnson continued. Photo Credit: SGranitz/WireImage André 3000 has influenced rap eccentrics his junior whose idiosyncratic sensibility is seen in their sound and clothes: California’s Tyler, the Creator, Cavalier from Brooklyn, and EarthGang, the Atlanta group for which Spelman’s curator in residence Karen Lowe brings OutKast to mind. Knowing André is knowing he comprised half of the classic rap duo OutKast, and the mention of their infamous video, “Hey Ya!,” will summon the image of him clad in a St. Patty’s green button-up, wide, white suspenders affixed to tartan trousers, and a green and black peppermint ascot, vigorously singing and bobbing his head with a shoulder-length bob. Those are the accouterments of an outstandingly dressed Black man, a dandy, to be sure, but that gives way to André centering himself in the video–self-replicating and standing in as seemingly minor characters. And in effect displaying his creative range. He’s a Black man who isn’t afraid to play with ideas, a quality Johnson describes as instructive. “Think about the Benjamin Bixby stuff. At some point, “André embraced prep and Americana through a distinctly Southern perspective,” he explains. Here Johnson also mentions Benjamin Bixby, the now-defunct clothing line by the artist that centered around Black dandyism. Photo Credit: Julia Beverly/Getty Images Lowe agrees. Three years ago, she spearheaded an open-air digital exhibition titled “The South Got Something to Say,” taken from the rapper’s 1995 Source Awards speech, where he called out the ceremony and its dismissal of the South’s contributions to the genre when we were shaping it in real-time. But the region, however influential and formative, hasn’t always been so free for Black men with expressive style. The curator mentions that the same can be said about Black culture at large. André 3000’s narrative is emancipatory; he represents a rare liberty. As a Black Southern man, he personifies a freedom that permits individuality without always being misunderstood. Lowe, who, like André 3000, is an Atlanta native, speaks to his free nature in “how he moves” and “not being defined by stereotypes and expectations.” To her, he appears to be mentally free. At times, he outright defies culturally imposed notions, like when he wears ultra-preppy clothing, he one-ups their assumed originators. Photo Credit: Barry Brecheisen/WireImage Other times, he plays into them as one of hip hop’s significant titans nonetheless. But he isn’t bound to either: in music or fashion. His references can be so rich they go over your head, such as his wearing a white wig in Outkast’s “Prototype” video, referencing P-Funk, a doo-wop band out of New Jersey. (A white wig he wore during one of his international concerts in 2014 is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Musical Crossroads Gallery.) Lessons aplenty can be learned from the explorer, the inventor, the experimenter, and the man that is André 3000—among them that a childlike enthusiasm for clothing can prevent one’s style from going stale, that our wardrobes can effectively be toy boxes. His strange swagger shows how the hodgepodge of influences that often make a terrific outfit should be honest. And that the most genuinely iconic dressers in American history stayed curious. Who else has done that while keeping as suave as the best-dressed men in our families? Source link

0 notes

Photo

Getty Images It’s endearing to witness someone’s style evolve as they age. It’s why many fashion lovers believe the youth-obsessed, youth-dependent fashion world should platform mature talent more often. Because as you age, your taste is increasingly defined. You wear clothes differently, with credibility, given you’ve had them forever, and every imperfection bespeaks your body’s contours. Your dress, one hopes, not only gains sophistication but stays ever-traceable to its roots. Of all that makes André 3000 special, that’s what I’ve found particularly remarkable lately since not all rappers carry the aesthetic that was once their signature well into adulthood. Where Busta Rhymes was once the unflinchingly offbeat dresser misunderstood by many, he now favors the conventional codes of hip-hop showiness. Some other artists of his era, too, have become faltering logomaniacs. And Snoop Dogg, whose Rastafarian-inspired locs mark the most, if only notable shift in his appearance, can hardly be seen in more than a bomber jacket, a matching set, requisite jewelry, and the occasional bucket hat. Photo Credit: M. Caulfield/WireImage for VH-1 Channel Right now it appears that there is a fashionable decline of the generals. But even a veteran fashion reporter immersed in the world of clothes has confessed to me that hers are much, much less a priority now than when she was working in the industry. Fashion as you age can indeed become the least important component of life. Not so for André! He remains a trailblazer in matters of the cloth, which throughout his career has covered his flawlessly pressed and permed hair in the form of a church lady-inspired headwrap, dandified his many silhouettes through suiting, been seer suckered for overalls worn with diva-like sunglasses and a ribbed beanie. His GQ Men of The Year photoshoot in that outfit is what many of us associate with what we’ve referred to as the artist’s “flute era.” His 2023 debut solo and now Grammy-nominated instrumental album New Blue Sun would make apparent his artistic expansion as a flutist, symbolizing his prevailing stylistic prowess despite puzzlements over his sonic shift. But that is the stuff that has made André 3000 the nonpareil figure we’ve come to adore. Patrick Johnson, a scholar and Sonoma State professor of American multicultural studies, sees the rapper’s style choices as metaphors that help narrate a bigger composition. “It’s the glasses; it’s the little notes he’s hitting in his fashion that says, ‘Okay, I’m thinking about these things differently, I’m flipping it,’” Johnson shared. But the reason he’s so relatable, so fly to us, is put plainly by Johnson. “André never feels outside of what other brothers are doing.” He isn’t entirely separate from or, say, weirdly above his peers who were “wearing jerseys and pink, furry Kangos. He was very much in relationship with what other Black men were doing,” Johnson continued. Photo Credit: SGranitz/WireImage André 3000 has influenced rap eccentrics his junior whose idiosyncratic sensibility is seen in their sound and clothes: California’s Tyler, the Creator, Cavalier from Brooklyn, and EarthGang, the Atlanta group for which Spelman’s curator in residence Karen Lowe brings OutKast to mind. Knowing André is knowing he comprised half of the classic rap duo OutKast, and the mention of their infamous video, “Hey Ya!,” will summon the image of him clad in a St. Patty’s green button-up, wide, white suspenders affixed to tartan trousers, and a green and black peppermint ascot, vigorously singing and bobbing his head with a shoulder-length bob. Those are the accouterments of an outstandingly dressed Black man, a dandy, to be sure, but that gives way to André centering himself in the video–self-replicating and standing in as seemingly minor characters. And in effect displaying his creative range. He’s a Black man who isn’t afraid to play with ideas, a quality Johnson describes as instructive. “Think about the Benjamin Bixby stuff. At some point, “André embraced prep and Americana through a distinctly Southern perspective,” he explains. Here Johnson also mentions Benjamin Bixby, the now-defunct clothing line by the artist that centered around Black dandyism. Photo Credit: Julia Beverly/Getty Images Lowe agrees. Three years ago, she spearheaded an open-air digital exhibition titled “The South Got Something to Say,” taken from the rapper’s 1995 Source Awards speech, where he called out the ceremony and its dismissal of the South’s contributions to the genre when we were shaping it in real-time. But the region, however influential and formative, hasn’t always been so free for Black men with expressive style. The curator mentions that the same can be said about Black culture at large. André 3000’s narrative is emancipatory; he represents a rare liberty. As a Black Southern man, he personifies a freedom that permits individuality without always being misunderstood. Lowe, who, like André 3000, is an Atlanta native, speaks to his free nature in “how he moves” and “not being defined by stereotypes and expectations.” To her, he appears to be mentally free. At times, he outright defies culturally imposed notions, like when he wears ultra-preppy clothing, he one-ups their assumed originators. Photo Credit: Barry Brecheisen/WireImage Other times, he plays into them as one of hip hop’s significant titans nonetheless. But he isn’t bound to either: in music or fashion. His references can be so rich they go over your head, such as his wearing a white wig in Outkast’s “Prototype” video, referencing P-Funk, a doo-wop band out of New Jersey. (A white wig he wore during one of his international concerts in 2014 is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Musical Crossroads Gallery.) Lessons aplenty can be learned from the explorer, the inventor, the experimenter, and the man that is André 3000—among them that a childlike enthusiasm for clothing can prevent one’s style from going stale, that our wardrobes can effectively be toy boxes. His strange swagger shows how the hodgepodge of influences that often make a terrific outfit should be honest. And that the most genuinely iconic dressers in American history stayed curious. Who else has done that while keeping as suave as the best-dressed men in our families? Source link

0 notes

Text

If You Ain't Cheating, You Ain't Trying...Part Three.

There is a mission in Red Dead Redemption 1 titled "Liars, Cheats, and Other Proud Americans" which I considered using as the title for this blogpost. That being said, the old adage "if you ain't cheatin', you ain't tryin'" is perhaps most closely associated with NASCAR.

And the poster child of cheating in NASCAR? None other than Smokey Yunick.

Henry "Smokey" Yunick had been a pilot in World War II and turned to NASCAR when he came home, driving in the early years of the sport. He is, however, known far more for his work as a crew chief. Particularly the cheated-up monstrosities from the 1966 season.

That story actually begins in 1965, when Dodge and Plymouth banned from competing as their powerful 426 Hemi engines had not met the 500 production units for homologation standards. In protest, Chrysler Corporation pulled all their teams and drivers, including NASCAR legends Richard Petty and David Pearson.

This was a major problem, thus, in 1966, NASCAR allowed the Hemi engine. Dodge and Plymouth returned, along with their star drivers, but in turn, the Ford factory entries pulled out in protest. Thus, Ford driver Curtis Turner instead signed for Smokey Yunick to drive a Chevrolet Chevelle.

Everyone knew this Chevelle was flagrantly illegal...but nobody knew exactly how.

The most popular explanation had been that Smokey built a 7/8ths scale replica of a Chevelle with an oversided engine.

In reality, car was the right size...sort of.

Smokey had raised the floor, lowered the body, moved the body three inches back on the frame for better weight distribution, smoothed out the underside to effectively give it a 90s F1 style flat floor, had the fenders and bumpers flush to the frame, and changed the angle of the front and rear window for better aerodynamics. Yeah.

It gets worse.

Come the August race at Atlanta Motor Speedway, NASCAR had reached an agreement with star Ford driver Fred Lorenzen to get him back in the sport. He, along with another famous crew chief, Junior Johnson, were basically given a blank check to do whatever they wanted for the race, they weren't going to get disqualified.

Thus, the 1966 Ford Galaxie, had its nose to the ground, its rear swung upwards for better aerodynamics, and the windshield was 20 degrees lower than normal. Not only that, but because it was an oval turning to the left, the left side of the car was a whole three inches lower than the right side. This is still done on oval racers today, but uhh...three inches is rather obscene. So obscene, in fact, that Lorenzen needed help just to get in and out of the car.

Painted yellow and with that swing from front to back, they called it the "Yellow Banana."

Smokey's Chevelle, in all fairness, had all the earlier infractions and by now had added an extension to the back of the roof that effectively functioned as an extra spoiler.

Both cars passed inspection.

Cheating had gotten so extreme that, for the 1967 Daytona 500, NASCAR would introduce body templates, essentially the shape that a car needed to be in order to be deemed legal. As advanced as its gotten now, NASCAR still more or less works based on templates.

The key thing is though, in NASCAR, Junior Johnson and Smokey Yunick are venerated. They were both part of the inaugural class of International Motorsports Hall of Famers in 1990. Johnson was then part of the inaugural class of the NASCAR Hall of Fame in 2010. Lorenzen and Turner, who drove those cars are Hall of Famers as well. If anything, they're more popular because they cheated.

With Smokey Yunick in particular, there's an almost folkloric aspect to his cheating.

One story goes that, shortly after NASCAR finally regulated the size of the fuel tanks, Smokey drove one of his cars into inspection. NASCAR took the car apart, removed the fuel tank, and told Smokey that they found nine things wrong with the car. Smokey shrugged, turned the car on, said "better make it ten" and drove off.

How? eleven feet of two-inch diameter fuel hose, wrapped around the car. Allegedly Smokey said "I coulda driven that sumbitch to Jacksonville." Realistically, it seems that much fuel hose would only be good enough for five gallons, and I'm not sure how fuel would get from the line to the engine without a fuel tank in between, but hey, five extra gallons is still an advantage.

Anyway, the point is that cheating is considered commonplace in NASCAR and the greatest cheaters are revered. Even now, there's a belief that the Championship Four cars at Phoenix are cheated up to high heaven because they know NASCAR isn't going to disqualify a championship contender.

Or the car that Dale Earnhardt Jr. drove at the 2001 Pepsi 400 - the first race at Daytona since his father's death at the 500 earlier that year - he was driving away from the pack in clean air on a restrictor plate track. Some people say it was a gentleman's agreement not to get in Jr's way if he was in position to win, some people say the car was the most blatantly illegal thing since Smokey Yunick. Others say the team did nothing wrong but NASCAR gave them a restrictor plate with a bigger opening to get the narrative they wanted.

Nobody knows for sure, but the point remains. Cheating is part of NASCAR, always has been, and it pretty much always will be. Whether it be "HMS never legal again" or "Dem Cheatin' Yoders" NASCAR twitter will constantly have somebody throwing out cheating allegations at one team or another, but nobody really blinks an eye at it. It's just part of the culture there.

Therefore, it's interesting to see the culture clash between the two worlds of American motorsports. On the NASCAR side, cheating is revered, with these stories being told and retold and exaggerated into the folklore of the sport. Meanwhile, on the Indycar side, it's turned Team Penske, and particularly Josef Newgarden, into a villain in the eyes of many fans.

For the two most popular racing series in America, they sure do view cheating through a different lens.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Getty Images It’s endearing to witness someone’s style evolve as they age. It’s why many fashion lovers believe the youth-obsessed, youth-dependent fashion world should platform mature talent more often. Because as you age, your taste is increasingly defined. You wear clothes differently, with credibility, given you’ve had them forever, and every imperfection bespeaks your body’s contours. Your dress, one hopes, not only gains sophistication but stays ever-traceable to its roots. Of all that makes André 3000 special, that’s what I’ve found particularly remarkable lately since not all rappers carry the aesthetic that was once their signature well into adulthood. Where Busta Rhymes was once the unflinchingly offbeat dresser misunderstood by many, he now favors the conventional codes of hip-hop showiness. Some other artists of his era, too, have become faltering logomaniacs. And Snoop Dogg, whose Rastafarian-inspired locs mark the most, if only notable shift in his appearance, can hardly be seen in more than a bomber jacket, a matching set, requisite jewelry, and the occasional bucket hat. Photo Credit: M. Caulfield/WireImage for VH-1 Channel Right now it appears that there is a fashionable decline of the generals. But even a veteran fashion reporter immersed in the world of clothes has confessed to me that hers are much, much less a priority now than when she was working in the industry. Fashion as you age can indeed become the least important component of life. Not so for André! He remains a trailblazer in matters of the cloth, which throughout his career has covered his flawlessly pressed and permed hair in the form of a church lady-inspired headwrap, dandified his many silhouettes through suiting, been seer suckered for overalls worn with diva-like sunglasses and a ribbed beanie. His GQ Men of The Year photoshoot in that outfit is what many of us associate with what we’ve referred to as the artist’s “flute era.” His 2023 debut solo and now Grammy-nominated instrumental album New Blue Sun would make apparent his artistic expansion as a flutist, symbolizing his prevailing stylistic prowess despite puzzlements over his sonic shift. But that is the stuff that has made André 3000 the nonpareil figure we’ve come to adore. Patrick Johnson, a scholar and Sonoma State professor of American multicultural studies, sees the rapper’s style choices as metaphors that help narrate a bigger composition. “It’s the glasses; it’s the little notes he’s hitting in his fashion that says, ‘Okay, I’m thinking about these things differently, I’m flipping it,’” Johnson shared. But the reason he’s so relatable, so fly to us, is put plainly by Johnson. “André never feels outside of what other brothers are doing.” He isn’t entirely separate from or, say, weirdly above his peers who were “wearing jerseys and pink, furry Kangos. He was very much in relationship with what other Black men were doing,” Johnson continued. Photo Credit: SGranitz/WireImage André 3000 has influenced rap eccentrics his junior whose idiosyncratic sensibility is seen in their sound and clothes: California’s Tyler, the Creator, Cavalier from Brooklyn, and EarthGang, the Atlanta group for which Spelman’s curator in residence Karen Lowe brings OutKast to mind. Knowing André is knowing he comprised half of the classic rap duo OutKast, and the mention of their infamous video, “Hey Ya!,” will summon the image of him clad in a St. Patty’s green button-up, wide, white suspenders affixed to tartan trousers, and a green and black peppermint ascot, vigorously singing and bobbing his head with a shoulder-length bob. Those are the accouterments of an outstandingly dressed Black man, a dandy, to be sure, but that gives way to André centering himself in the video–self-replicating and standing in as seemingly minor characters. And in effect displaying his creative range. He’s a Black man who isn’t afraid to play with ideas, a quality Johnson describes as instructive. “Think about the Benjamin Bixby stuff. At some point, “André embraced prep and Americana through a distinctly Southern perspective,” he explains. Here Johnson also mentions Benjamin Bixby, the now-defunct clothing line by the artist that centered around Black dandyism. Photo Credit: Julia Beverly/Getty Images Lowe agrees. Three years ago, she spearheaded an open-air digital exhibition titled “The South Got Something to Say,” taken from the rapper’s 1995 Source Awards speech, where he called out the ceremony and its dismissal of the South’s contributions to the genre when we were shaping it in real-time. But the region, however influential and formative, hasn’t always been so free for Black men with expressive style. The curator mentions that the same can be said about Black culture at large. André 3000’s narrative is emancipatory; he represents a rare liberty. As a Black Southern man, he personifies a freedom that permits individuality without always being misunderstood. Lowe, who, like André 3000, is an Atlanta native, speaks to his free nature in “how he moves” and “not being defined by stereotypes and expectations.” To her, he appears to be mentally free. At times, he outright defies culturally imposed notions, like when he wears ultra-preppy clothing, he one-ups their assumed originators. Photo Credit: Barry Brecheisen/WireImage Other times, he plays into them as one of hip hop’s significant titans nonetheless. But he isn’t bound to either: in music or fashion. His references can be so rich they go over your head, such as his wearing a white wig in Outkast’s “Prototype” video, referencing P-Funk, a doo-wop band out of New Jersey. (A white wig he wore during one of his international concerts in 2014 is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Musical Crossroads Gallery.) Lessons aplenty can be learned from the explorer, the inventor, the experimenter, and the man that is André 3000—among them that a childlike enthusiasm for clothing can prevent one’s style from going stale, that our wardrobes can effectively be toy boxes. His strange swagger shows how the hodgepodge of influences that often make a terrific outfit should be honest. And that the most genuinely iconic dressers in American history stayed curious. Who else has done that while keeping as suave as the best-dressed men in our families? Source link

0 notes

Text

Ypsilanti, Michigan, 1945. Engineer Preston Tucker dreams of designing the car of future, but his innovative envision will be repeatedly sabotaged by his own unrealistic expectations and the Detroit automobile industry tycoons. Credits: TheMovieDb. Film Cast: Preston Tucker: Jeff Bridges Vera: Joan Allen Abe: Martin Landau Eddie: Frederic Forrest Jimmy: Mako Howard Hughes: Dean Stockwell Junior: Christian Slater Marilyn Lee: Nina Siemaszko Frank: Marshall Bell Kerner: Peter Donat Alex: Elias Koteas Kirby: Jay O. Sanders Noble: Corin Nemec Stan: Don Novello Johnny: Anders Johnson Bennington: Dean Goodman Ferguson’s Agent: John X. Heart Millie: Patti Austin Stan’s Assistant: Sandy Bull Judge: Joe Miksak Floyd Cerf: Scott Beach Oscar Beasley: Roland Scrivner Narrator (voice): Bob Safford Doc: Larry Menkin Fritz: Ron Close Dutch: Joe Flood Gas Station Owner: Leonard Gardner Garage Owner: Bill Bonham Ferguson’s Secretary #1: Abigail van Alyn Ferguson’s Secretary #2: Taylor Gilbert Woman on Steps: David Booth Newscaster (voice): Al Hart Security Guard: Cab Covay Man in Audience: James Cranna Board Member: Bill Reddick Mayor: Ed Loerke Head Engineer: Jay Jacobus Bennington’s Secretary: Anne Lawder Singing Girl #1: Jeanette Lana Sartain Singing Girl #2: Mary Buffett Singing Girl #3: Annie Stocking Recording Engineer: Michael McShane Tucker’s Secretary #1: Hope Alexander-Willis Tucker’s Secretary #2: Taylor Young Police Sergeant: Jim Giovanni Reporter at Trial: Joe Lerer Ingram: Morgan Upton SEC Agent: Ken Grantham Blue: Mark Anger Jury Foreman: Al Nalbandian Senator Homer Ferguson (uncredited): Lloyd Bridges Girl at Mellon Publicity Event (uncredited): Sofia Coppola Film Crew: Executive Producer: George Lucas Director: Francis Ford Coppola Producer: Fred Roos Additional Music: Carmine Coppola Director of Photography: Vittorio Storaro Production Design: Dean Tavoularis Editor: Priscilla Nedd-Friendly Casting: Janet Hirshenson Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Richard Beggs Producer: Fred Fuchs Casting: Jane Jenkins Music Editor: Mark Adler Supervising Sound Editor: Gloria S. Borders Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Tom Johnson Set Decoration: Armin Ganz Costume Designer: Milena Canonero Unit Production Manager: Ian Bryce Foley Artist: Dennie Thorpe Sound Effects Editor: Tim Holland Leadman: Doug von Koss Second Unit Director: Buddy Joe Hooker Assistant Costume Designer: Judianna Makovsky Assistant Makeup Artist: Karen Bradley Set Designer: Jim Pohl Camera Operator: Jamie Anderson Foley Editor: Sandina Bailo-Lape Stunts: Jimmy Nickerson Screenplay: Arnold Schulman Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Randy Thom ADR Editor: Louise Rubacky Original Music Composer: Joe Jackson Researcher: Anahid Nazarian Assistant Sound Designer: Mildred Iatrou Location Casting: Aleta Chappelle Stunts: Gary McLarty Screenplay: David Seidler First Assistant Director: H. Gordon Boos Stunts: Dick Ziker Makeup Artist: Richard Dean ADR Editor: Tom Bellfort Art Direction: Alex Tavoularis Assistant Hairstylist: Terry Baliel Technical Advisor: Enrico Umetelli Property Master: Douglas E. Madison Script Supervisor: Wilma Garscadden-Gahret Still Photographer: Ralph Nelson Jr. Stunts: Steve M. Davison Sound Effects Editor: Robert Shoup Stunts: Tim A. Davison Assistant Sound Editor: Martha Pike Hairstylist: Lyndell Quiyou Costume Supervisor: Winnie D. Brown Assistant Sound Editor: Michele Perrone Foley Editor: Diana Pellegrini First Assistant Camera: Billy Clevenger Assistant Property Master: Douglas T. Madison Construction Coordinator: John J. Rutchland Jr. Unit Publicist: Susan Landau Finch Second Assistant Director: L. Dean Jones Jr. Production Sound Mixer: Michael Evje Assistant Sound Editor: Clare C. Freeman Assistant Sound Editor: Paige Sartorius Location Manager: Rory Enke Second Assistant Director: Daniel R. Suhart Gaffer: Pat Fitzsimmons Dialogue Editor: Melissa Dietz Associate Producer: Teri Fettis-D’Ovidio Boom Operator: D. G. Fisher Special Effects Supervisor: David Pier Production Accountant: Joe Murphy Negative Cutter: Donah Bassett Second Assistant C...

#1940s#automobile industry#based on true story#biography#car designer#Chicago#illinois#industrial espionage#Top Rated Movies

0 notes

Text

O'Shaquie Foster Ready to Defend Junior Lightweight Crown against Abraham Nova

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Follow @Frontproofmedia!function(d,s,id){var js,fjs=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],p=/^http:/.test(d.location)?'http':'https';if(!d.getElementById(id)){js=d.createElement(s);js.id=id;js.src=p+'://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js';fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js,fjs);}}(document, 'script', 'twitter-wjs');

Published: February 14, 2024

Foster-Nova, Andres Cortes-Bryan Chevalier, and Bruce Carrington-Bernard Torres will be broadcast live on ESPN, ESPN Deportes, and ESPN+ beginning at 9 p.m. ET/6 p.m. PT

NEW YORK — WBC junior lightweight world champion O’Shaquie “Ice Water” Foster (21-2, 12 KOs) and Abraham “El Super” Nova (23-1, 16 KOs) are ready to lock horns in the main event of an ESPN-televised tripleheader this Friday, Feb. 16 at The Theater at Madison Square Garden. This will be the second title defense for Foster, a native of Orange, Texas, who salvaged his title with a come-from-behind 12th-round knockout over Rocky Hernandez last October. In the 10-round junior lightweight co-feature, Andres “Savage” Cortes (20-0, 11 KOs) takes on Puerto Rican contender Bryan Chevalier (20-1-1, 16 KOs). Rising featherweight Bruce “Shu Shu” Carrington (10-0, 6 KOs), the latest fistic prodigy from Brownsville, Brooklyn, will face Filipino-born Bernard Torres (18-1, 8 KOs) in the 10-round televised opener. Foster-Nova, Cortes-Chevalier and Carrington-Torres will be broadcast live on ESPN, ESPN Deportes and ESPN+ at 9 p.m. ET/6 p.m. PT. The ESPN+-streamed undercard (5:20 p.m. ET/2:20 p.m. PT) will feature the return of Italian heavyweight Guido Vianello (11-1-1, 8 KOs) in an eight-rounder against Moses Johnson (11-1-2, 8 KOs), as well as U.S. Olympian Tiger Johnson (11-0, 5 KOs), who risks his unbeaten record against Paulo Galdino (13-7-2, 9 KOs) in an eight-round junior welterweight tilt. Promoted by Top Rank, in association with Murphys Boxing and 12 Rounds Promotion, tickets are on sale via Ticketmaster.com. At Wednesday's press conference, this is what the fighters had to say. O’Shaquie Foster “The journey has been everything. The ups and downs. Growing as a person. I’ve matured now, mentally and physically. Words can’t explain how I feel, but I’m ready.” “It was crazy {against Rocky Hernandez}. We shocked the world. And I’m here to do it again. Everybody calls me Shock, and we’re going to keep doing it.” “We’ve been calling out Nova for years. He knows it. His excuse was that my name wasn’t big enough. Funny how the tables turn. I’m ready, and I’m familiar with his style.” “I did everything in the gym. We are prepared. Come Friday night, we will dominate and put on a show.” Abraham Nova “Fighting for a world title is a dream come true. I can’t let this opportunity slip by. I’ve wanted this for so long. Now I have this opportunity. So, I’m super excited and super motivated.” “I like to take control of things in my career. It’s the main reason I picked boxing. It’s an individual sport. I can be in control.” “I’ve got to put my trust in God. Everything in the gym has been done. You know what I bring and what I come with. The pressure will be on. The IQ will be on. Everything will be on. I will just have to adjust and come out with the victory.” Andres Cortes “I’m really excited to be here. First time here. Let’s get the show started." "You can expect another statement from me. You’ll see me taking another step towards a world title.” “I see a world title in my future. I’m here to take care of Bryan first. But maybe one day we can make that fight happen.” Bryan Chevalier “The ring is the same throughout the world. It’s a square. It’ll just be me, him and the referee. We’re ready to give a great show to boxing fans. “Styles make fights. I prepared to give the best of me. I will accommodate to what he has. He will have to accommodate to what I have. Without a doubt, it will be a war between Mexico and Puerto Rico.” Bruce Carrington “I love these opportunities to fight at home. Bernard Torres is a southpaw. It’s always interesting to fight against a southpaw. He's a good fighter. 18-1. Great record. He shows a lot of will and skill. There’s nothing more you can ask for in a opponent.” “He's a good fighter. But with my experience, confidence, and work ethic, I know that I’ve got a Plan A through Z and even more to take care of Bernard Torres.” Bernard Torres “Growing up in boxing, it’s a dream to fight here. So, I’m happy to box here at Madison Square Garden. I am really happy for this opportunity. I’m very prepared. I had a really great camp. I’m really happy and ready to go.”

Friday, February 16

ESPN, ESPN Deportes & ESPN+ (9 p.m. ET/6 p.m. PT)

O'Shaquie Foster vs. Abraham Nova, 12 rounds, Foster's WBC junior lightweight world title

Andres Cortes vs. Bryan Chevalier, 10 rounds, junior lightweight Bruce Carrington vs. Bernard Torres, 10 rounds, featherweight

ESPN+ (5:20 p.m. ET/2:20 p.m. PT)

Guido Vianello vs. Moses Johnson, 8 rounds, heavyweight Isaah Flaherty vs. Julien Baptiste, 6 rounds, middleweight Ofacio Falcon vs. Edward Ceballos, 6 rounds, junior lightweight Tiger Johnson vs. Paulo Galdino, 8 rounds, junior welterweight Euri Cedeno vs. Antonio Todd, 8 rounds, middleweight Arnold Gonzalez vs. Charles Stanford, 6 rounds, welterweight

(Featured Photo: Mikey Williams/Top Rank)

0 notes