#Journal of Polynesian Archaeology and Research

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Inaugural issue of the Journal of Polynesian Archaeology and Research

Readers may be interested in this newly-launched journal in an adjacent region, the Journal of Polynesian Archaeology and Research which is Open Access.

Readers may be interested in this newly-launched journal in an adjacent region, the Journal of Polynesian Archaeology and Research which is Open Access. Welcome to the inaugural issue of the Journal of Polynesian Archaeology and Research (JPAR). We have been working with colleagues at the University of Hawai‘i Press for the past two years to establish and launch this open-access journal that…

View On WordPress

#Journal of Polynesian Archaeology and Research#Pacific Ocean#Polynesia (culture)#University of Hawaii

0 notes

Photo

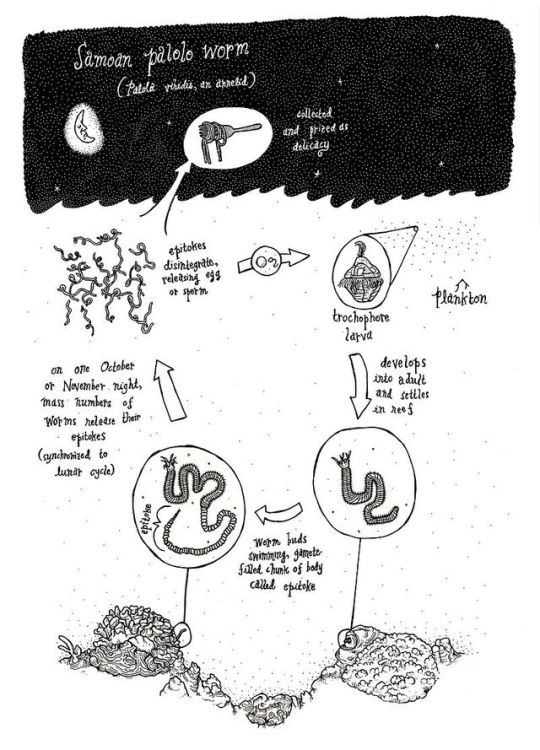

If you are interested in yams, Polynesia, folklore, linguistics, highly-detailed gardening calendars, island ecology, or the sudden simultaneous appearance of hundreds of thousands of sea-worms on a moonlit night, you might enjoy this: Sean P. Connaughton. “A Story of Yams, Worms, and Change from Ancestral Polynesia.” The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology Vol. 7 (2012).

Illustration of the Eunicea viridis (Polynesia’s palolo worm) life cycle, above, by Dakuhippo.

To paraphrase this research:

Centuries ago, when Lapita cultures apparently started moving from Melanesia into the western portions of Polynesia centered around Tonga, it seems that horticultural practices, especially regarding the growing of yams, were (like today) extremely important given the distinct dry and wet seasons in the area. Calendars were based on lunar cycles and the lunar months; on some islands, it seems that many individual days of a lunar month could be given a different name to reflect lunar-influenced marine events occurring on that date. So, to mark the best time to start planting yams in order to avoid the dry season, early residents of western Polynesia apparently purposely linked yam season with other ecological events around the same time of year.

The lunar calendar in western Polynesia was augmented with folkloric stories promoting the importance of what were called the palolo months, occurring between September and November. Palolo is a local name for giant polycheate sea-worms, especially Eunicea viridis, closely-related to and of the same genus as the famous predatory Bobbit worm. These months included the seasonal rising of reproductive segments of the annelid sea-worm of the Eunicidae family in certain nearby ocean areas. In other words, there is a massive Worm Event(TM) where a bunch of spaghetti-like worms rise to the surface in giant masses.

The arrival of the worms marked a definitive climatic shift from dry to wet season, and therefore marked the arrival of yam-growing season. By observing the worms’ behavior, island residents could accurately anticipate the most successful times for food cultivation. The worm event was, and still is, mostly limited to Tonga, Samoa, and parts of far western Polynesia, where the earlier Polynesian voyages originated; the seasonal worm event apparently does not occur across most of Polynesia, especially east of Tonga and Samoa.

However, even though the worms are absent in, say, Tahiti, the lunar calendars of Polynesians living in Tahiti and other locations far to the east of Tonga still include references to the palolo months. So, essentially, the horticultural activity surrounding yam-growing season was so important in western Polynesia that the sea-worm event itself also became an important part of the western Polynesia lunar calendar; the yams and the worms became so intertwined that, as Polynesian people later migrated much farther eastward towards Tahiti, the worm references still appear in language and calendars of communities living thousands of kilometers away, and in calendars that today still exist a few centuries later in history.

In Tonga, Samoa, and nearby islands, the annual arrival of palolo worms is still a big event. (Palolo worm harvest also happens in parts of Indonesia.)

-

Just some fun details about what some people call: “the yam calendar.”

78 notes

·

View notes

Link

How did the massive stone statues on Rapa Nui — better known as Easter Island — end up wearing stone hats? It may have taken ramps, ropes and a remarkably small workforce. That’s the finding of a new study. But not everyone buys its conclusion.

The largest of those hats are nearly two meters (6.6 feet) across and weigh some 12 metric tons (26,500 pounds). Many scientists had wondered how the statues got their massive headgear, which are made from a separate piece — and different type of stone — than each statue.

Polynesian travelers first settled the island by the 1200s. The 164-square-kilometer (63.3-square-mile) island sits in the Pacific Ocean, about midway between the west coast of Chile (in South America) and the Pacific island chain of Tahiti. Islanders made nearly 1,000 human statues from volcanic rock. These figures stand up to 10 meters (33 feet) tall and weigh as much as 74 metric tons (160,000 pounds). Hundreds of them were placed atop stone platforms, many on the island’s coast.

Sean Hixon is an archaeologist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. He was part of a research team that has been studying the famous stone heads and their toppers, called pukao. The team focused on dozens of the hats.

The researchers looked for things the huge stone hats had in common that might explain how they had been made and moved. What they learned now suggests that the cylindrical headgear could have been rolled up ramps to the top of the statues. Then the stones could have been tipped over to sit upright atop the giant heads. It may have taken no more than 15 people to manage the feat, the researchers say.

They shared their analysis online May 31, 2018 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

More from Smithsonian MagazineNew Research Rewrites the Demise of Easter Island

The story of Easter Island—home to the famous moai monoliths—is a tragic one. But depending on the individual you ask, the harbingers of its early demise aren’t always the same.

In one version, the island—a remote outpost thousands of miles off the western coast of South America—was settled in the 13th century by a small group of Polynesians. Over time, the migrants papered the landscape, once rich with trees and rolling hills, with crop fields and monoliths. The transformation eroded the nutrient-rich soil, catapulting the island onto a path of destruction. As the trees dwindled, so did the people who had felled them: By the time Dutch explorers arrived on Easter Island in 1722, this early society had long since collapsed.

But in recent years, evidence has mounted for an alternative narrative—one that paints the inhabitants of the island they called Rapa Nui not as exploiters of ecosystems, but as sustainable farmers who were still thriving when Europeans first made contact. In this account, other factors conspired to end a pivotal era on Easter Island.

The latest research to support this idea, published recently in the Journal of Archaeological Science, comes from an analysis of the island’s ahu—the platforms supporting the moai, which honor the Rapa Nui’s ancestors. Using a combination of radiocarbon dating and statistical modeling, a team of researchers has now found that the spectacular statues’ construction continued well past 1722, post-dating the supposed decline of the people behind the moai.

“Monument-building and investment were still important parts of [these people’s] lives when [the European] visitors arrived,” says study author Robert J. DiNapoli, an anthropologist at the University of Oregon, in a statement.

Data amassed from 11 Easter Island sites shows that the Rapa Nui people began assembling the moai sometime between the early 14th and mid-15th centuries, continuing construction until at least 1750, reports Sarah Cascone for artnet News. These numbers fall in line with historical documents from the Dutch and Spanish, who recorded observations of rituals featuring the monuments through the latter part of the 18th century. The only true ceiling for the moai’s demise is the year 1774, when British explorer James Cook arrived to find the statues in apparent ruins. And despite previous accounts, researchers have failed to find evidence pointing to any substantial population decline prior to the 18th century, writes Catrine Jarman for the Conversation.

While the Europeans’ stays “were short and their descriptions brief and limited,” their writings “provide useful information to help us think about the timing of building,” says DiNapoli in the statement.

The revised timeline of the monoliths also speaks to their builders’ resilience. As foreign forces came and went from the island, they brought death, disease, destruction and slavery within its borders, explains study author Carl Lipo, an anthropologist at Binghamton University, in the statement.

“Yet,” he adds, “the Rapa Nui people—following practices that provided them great stability and success over hundreds of years—continue their traditions in the face of tremendous odds.”

Eventually, however, a still-mysterious combination of factors shrank the population, and by 1877, just over 100 people remained on Easter Island, according to the Conversation. (The Rapa Nui, who are still around today, eventually recovered.)

The trees, too, suffered, though not entirely at human hands: The Polynesian rat, an accidental stowaway that arrived with the Rapa Nui and began to gnaw their way through palm nuts and saplings, was likely partly to blame, reported Whitney Dangerfield for Smithsonian magazine in 2007.

But Lipo points out the many ways in which the Rapa Nui have persevered in modern times.

“The degree to which their cultural heritage was passed on—and is still present today through language, arts and cultural practices—is quite notable and impressive,” he says in the statement.

This “overlooked” narrative, Lipo adds, is one that “deserves recognition.”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-research-rewrites-demise-easter-island-180974172/

0 notes

Note

Could you tell us more about polynesian ecological knowledge?

Thanks for the ask. As usual, I’d always recommend trying to read the work of locals or Indigenous people of a given region, if they are willing to share their knowledge with non-Indigenous or non-local people. Rapa Nui was not the only Polynesian island group to have been conspicuously abandoned; it seems that soil degradation was somewhat common, especially on smaller and more ecologically sensitive islands. This might be a result of the Polynesian habit of exploring and “testing” islands for potential long-term settlement. I am not a good source of info on specific Polynesian tactics to maintain soil, but I might be able to recommend some sources that can answer how soil was replenished. (I’d also look into the Polynesian cultivation of taro, breadfruit, and pandanus). I’ll try to keep this post short, but like I mentioned in an earlier post, I spent several years periodically writing and updating two theses on Polynesian and Micronesian environmental knowledge and historical ecology. And, again, I did try to use mostly sources from Polynesian and Micronesian people or scholars close to and respectful of Oceanian cultures. I’m not really still all that knowledgeable or up-to-date on these subjects (it’s more like, I went through an “Oceania” phase) so take what I recommend with a grain of salt. That said, I carried this book in my overstuffed backpack, or kept it on my desk, just about everyday during that time. This is a good place to start exploring Polynesian use of plants for food crops, construction, and for navigation/voyaging.

So as I’ve blabbered on about before, I am so excited by Polynesian traditional ecological knowledge because it’s my impression that this kind of environmental knowledge, on islands in the Pacific, is uniquely impressive because (1) of the remoteness of islands, even from nearby islands occupied by related communities, meaning that cultivation and acquiring food requires extremely reliable maintenance of environmental knowledge, because in the middle of the ocean, you can’t exactly call for rescue or assistance easily; (2) the small size of many islands, the delicate sensitivity of such small islands, the essentially-closed ecological system, and easily depleted health of soil on islands means that unsustainable horitcultural or agricultural practices, or one bad seasonal harvest, can doom an entire island’s community to starvation; and (3) all of this sophisticated environmental knowledge was historically transmitted from generation to generation through oral tradition and storytelling, in the absence of written languages. Knowledge of the stars is of course an aspect of environmental knowledge. So this oral transmission of information in Polynesia is spectacular, especially with regards to astronomy and the ocean itself. For some island societies, intimately knowing the stars was a matter of life and death; the stars not only guided navigation, but could tell you that the annual migration of a certain fish was a few days away, or that a marine worm mating event would soon happen near the ocean surface a few kilometers to the east, meaning you could harvest them and eat (ask me more about the worm harvest). And it’s not like there was a written encyclopedia you could consult to identify stars; in some communities, like in Kiribati, even laypeople and teenagers (not just a priest class who had committed their entire life to navigation) can name over 770 different stars in the sky. (!)

Many individual Oceanian islands have a very clear archaeological record demonstrating the arrival of humans and food crops, the development of consistent horticultural practices, and, in some cases, the abandonment of settlement on the island. So a lot of archaeological work on historical ecology (especially the work of Patrick V. Kirch) can be enlightening in trying to understand which food crops were planted, how sustainable they were, and what the long-term ecological effects on soil were. However, the self-reported knowledge and oral histories of Polynesian/Oceanian people themselves are, probably unsurprisingly, the best sources for learning about plant use, horticulture, and related subjects.

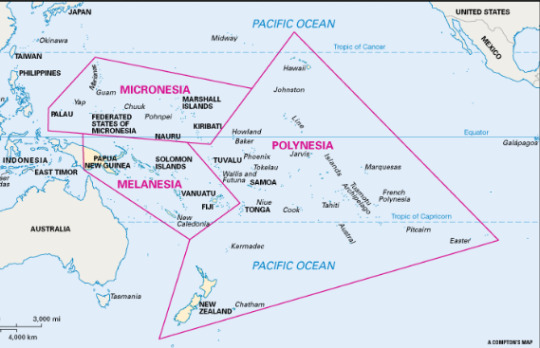

I’m honestly not entirely sure how the Euro-American popular consciousness perceives Polynesia, aside from the typical colonialist fascination with “the exotic” and tropicality. Mayhaps some people would be surprised by just how big and expansive the South Pacific is? I know that Polynesia and Oceania are often perceived as “tropical,” but there are still many islands traditionally inhabited by Polynesian cultures that exist south of the Tropic of Capricorn, in some temperate and seasonally “chilly” climates, including Aotearoa (New Zealand). It seems that many Micronesian islands share many traditions with Polynesia, especially including horticulture, astronomy, and navigation. So just for reference, here’s a map of Oceania:

Here are a few singular sources that contain a lot of info on horticulture, environmental knowledge, and environmental change in Oceania:

– Historical Ecology in the Pacific Islands. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Terry L. Hunt. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.– Cultural Ecology in the Pacific Islands. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Terry L. Hunt. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.– pretty much all the work of Patrick V. Kirch, who focuses on pre-European historical ecology and environmental change of Polynesia, often using thorough archaeological research and self-reported local Indigenous histories– the work of Patrick D. Nunn is also widely respected; he focuses more on Polynesian/Micronesian myth and folklore, but a lot of this folklore has to do with ecology/environments– The People of the Sea: Environment, Identity, and History in Oceania. Paul D’Arcy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006.– The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. 2008. (A little too Western/Euro-American in its perspective, but there is a lot of discussion of historical ecology of the islands.)– Plants and the Migrations of Pacific Peoples: A Symposium (1963).– Migrations, Myth and Magic from the Gilbert Islands. Arthur Grimble. London: Routledge, 1972. (Mostly about navigation, astronomy, and folklore, but includes lots of firsthand accounts from talented traditional navigators as they discuss the importance of plants in voyages.)

—-

And here are some of the better sources - specifically involving ethnobotany and environmental change - that I’ve used in essays:

Abbott, Isabella A. “Polynesian Uses of Seaweed.” In Islands, Plants, and Polynesians: An Introduction to Polynesian Ethnobotany. Edited by Paul Alan Cox and Sandra Anne Bannack. Portland, Oregon: Dioscorides Press, 1991.

Allen, Melinda S. “Coastal Morphogenesis, Climatic Trends, and Cook Islands Prehistory.” In Cultural Ecology in the Pacific Islands. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Terry L. Hunt. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Anderson, Atholl. “Epilogue: Changing Archaeological Perspectives upon Historical Ecology in the Pacific Islands.” Pacific Science 63:4 (2009).

Aswani, Shankar and Michael W. Graves. “The Tongan Maritime Expansion: A Case in the Evolutionary Ecology of Social Complexity.” Asian Perspectives 37:2 (1998).

Bannack, Sandra Anne. “Plants and Polynesian Voyaging.” In Islands, Plants, and Polynesians: An Introduction to Polynesian Ethnobotany, edited by Paul Alan Cox and Sandra Anne Bannack. Portland, Oregon: Dioscordes Press, 1991.

Burley, David V. “Archaeological Demography and Population Growth in the Kingdom of Tonga: 950 BC to the Historical Era.” In The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Cunningham, Sean P. “A Story of Yams, Worms, and Change from Ancestral Polynesia.” The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 7:2 (2012).

D’Arcy, Paul. The People of the Sea: Environment, Identity, and History in Oceania. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

Gunson, Niel. “Understanding Polynesian Traditional History.” The Journal of Pacific History 28:2 (1993).

Jost, XM; et al. “Ethnobotanical survey of cosmetic plants used in Marquesas Islands (French Polynesia).” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016).

Kirch, Patrick V. “Changing Landscapes and Sociopolitcal Evolution in Mangaia, Central Polynesia.” In Historical Ecology in the Pacific Islands. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Terry L. Hunt. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Kirch, Patrick V. The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Kirch, Patrick V. “’Like Shoals of Fish’: Archaeology and Population in Pre-Contact Hawaii.” In The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Kirch, Patrick V. “Solstice observations in Mangareva, French Polynesia.” Archeoastronomy: the Journal of Astronomy in Culture 18 (2004).

Kirch, Patrick V. “Temple Sites in Kahi Kinui, Maui, Hawaiian Islands: Their Orientations Decoded.” Antiquity 78:299 (2004).

Kirch, Patrick V. and Jean-Louis Rallu. “Long-term Demographic Evolution in the Pacific Islands.” In The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Ladefoged, Thegn N. and Michael W. Graves. “Modelling Agricultural Development and Demography in Kohala, Hawaii.” In The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Luomala, Katharine. Ethnobotany of the Gilbert Islands. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum, 1953.

Merlin, MD. “A History of Ethnobotany in Remote Oceania.” Pacific Science Vol. 54 No. 3 (2000).

Ragone, Diane. “Ethnobotany of Breadfruit in Polynesia.” In Islands, Plants, and Polynesians: An Introduction to Polynesian Ethnobotany. Edited by Paul Alan Cox and Sandra Anne Bannack. Portland, Oregon: Dioscorides Press, 1991.

Rallu, Jean-Louis. “Pre- and Post-Contact Population in Island Polynesia: Can Projections Meet Retrodictions?” In The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Stone, Benjamin C. “The Role of Pandanus in the Culture of the Marshall Islands.” In Plants and the Migrations of Pacific Peoples: A Symposium. Edited by Jacques Barrau. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1963.

Tuljapurkar, Shirpad, Charlotte Lee and Michelle Figgs. “Demography and Food in Early Polynesia.” In The Growth and Collapse of Pacific Island Societies: Archaeological and Demographic Perspectives. Edited by Patrick V. Kirch and Jean-Louis Rallu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

–

These are just the sources exclusively dealing with plants, soil, and land use. Most of the sources I’m familiar with deal more with folklore and mythology, which are still pretty relevant to Polynesian environmental history, because much of the folklore has to do with understanding the environment. Most of these sources focus on understanding the ocean, sea life, and astronomy. Let me know if you’re interested in those.

And as long as we’re discussing Polynesian historical ecology, Polynesia also hosted some of the most unique and interesting relict species, strange and ancient endemic species left over from the Pleistocene that were able to hold on to existence on islands until human arrival. Like terrestrial and tree-climbing crocodiles, weird nocturnal birds, and frogs that somehow crossed the ocean despite their permeable amphibian skin. Just, Oceania is a really cool region.

Thanks again for the ask. :)

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

How did the massive stone statues on Rapa Nui — better known as Easter Island — end up wearing stone hats? It may have taken ramps, ropes and a remarkably small workforce. That’s the finding of a new study. But not everyone buys its conclusion.

The largest of those hats are nearly two meters (6.6 feet) across and weigh some 12 metric tons (26,500 pounds). Many scientists had wondered how the statues got their massive headgear, which are made from a separate piece — and different type of stone — than each statue.

Polynesian travelers first settled the island by the 1200s. The 164-square-kilometer (63.3-square-mile) island sits in the Pacific Ocean, about midway between the west coast of Chile (in South America) and the Pacific island chain of Tahiti. Islanders made nearly 1,000 human statues from volcanic rock. These figures stand up to 10 meters (33 feet) tall and weigh as much as 74 metric tons (160,000 pounds). Hundreds of them were placed atop stone platforms, many on the island’s coast.

Sean Hixon is an archaeologist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. He was part of a research team that has been studying the famous stone heads and their toppers, called pukao. The team focused on dozens of the hats.

The researchers looked for things the huge stone hats had in common that might explain how they had been made and moved. What they learned now suggests that the cylindrical headgear could have been rolled up ramps to the top of the statues. Then the stones could have been tipped over to sit upright atop the giant heads. It may have taken no more than 15 people to manage the feat, the researchers say.

They shared their analysis online May 31 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui, is a 63-square-mile spot of land in the Pacific Ocean. In 1995, science writer Jared Diamond popularized the “collapse theory” in a Discover magazine story about why the Easter Island population was so small when European explorers arrived in 1722. He later published Collapse, a book hypothesizing that infighting and an overexploiting of resources led to a societal “ecocide.” However, a growing body of evidence contradicts this popular story of a warring, wasteful culture.

Scientists contend in a new study that the island’s most iconic features are also the best evidence that ancient Rapa Nui society was more sophisticated than previously thought, and the biggest clue lies in the island’s most iconic features.

The iconic “Easter Island heads,” or moai, are actually full-bodied but often partially buried statues that cover the island. There are almost a thousand of them, and the largest is over 70 feet tall. Scientists hailing from UCLA, the University of Queensland, and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago believe that, much like Stonehenge, the process by which these monoliths were created is indicative of a collaborative society.

Their research was published in August 2018 in the Journal of Pacific Archaeology.

Study co-author and director of the Easter Island Statue Project Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Ph.D., is focused on measuring the visibility, number, size, and location of the moai. She tells Inverse that “visibility, when linked to geography, tells us something about how Rapa Nui, like all other traditional Polynesian societies, is built on family identity.”

Van Tilburg and her team say that understanding how these families interacted with the craftsmen who made the tools that helped create the giant statues is indicative of how different parts of Rapa Nui society interacted.

Previous excavations led by Tilburg revealed that the moai were created from basalt tools. In this study, the scientist focused on figuring out where on the island the basalt came from. Between 1455 and 1645 AD there was a series of basalt transfers from quarries to the actual location of the statues — so the question became, which quarry did they come from?

Chemical analysis of the stone tools revealed that the majority of these instruments were made of basalt that was dug up from one quarry. This demonstrated to the scientists that, because everyone was using one type of stone, there had to be a certain level of collaboration in the creation of the giant statues.

“There was more interaction and collaboration.”

“We had hypothesized that elite members of the Rapa Nui culture had controlled resources and would only use them for themselves,” lead author and University of Queensland Ph.D. candidate Dale Simpson Jr. tells Inverse. “Instead, what we found is that the whole island was using similar material, from similar quarries. This led us to believe that there was more interaction and collaboration in the past that has been noted in the collapse narrative.”

Simpson explains that the scientists intend to continue to map the quarries and perform other geochemical analysis on artifacts, so they can continue to “paint a better picture” about Rapa Nui’s prehistoric interactions.

After Europeans arrived on the island, slavery, disease, and colonization decimated much of Rapa Nui society — although its culture continues to exist today. Understanding exactly what happened in the past there is key to recognizing a history that became clouded by colonial interpretation.

“What makes me excited is that through my long-term relationship with the island, I’ve been able to better understand how people in the ancient past interacted and shared information — some of this interaction can be seen today and between thousands of Rapa Nui who still live today,” says Simpson. “In short, Rapa Nui is not a story about collapse but about survival!”

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/easter-island-a-popular-theory-about-its-ancient-people-might-be-wrong

0 notes

Text

More pieces to the Polynesian puzzle

Native Americans had a genetic and cultural influence on Polynesia more than five centuries before the arrival of Europeans in the region, a new study suggests.

And it didn’t all start in the obvious place – Rapa Nui (Easter Island) – according to the international team of researchers.

They say evidence shows first contact was on one of the archipelagos of eastern Polynesia, such as the South Marquesas, as proposed by the late Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, who made his famous drift voyage from Peru to Polynesia on the raft Kon-Tiki in 1947.

The new study, which is described in a paper in the journal Nature, was led by Andrés Moreno-Estrada, from Stanford University, US, and Alexander Ioannidis from Mexico’s National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity.

With colleagues they examined the genomes of more than 817 people from 17 island populations and 15 Pacific coast Native American groups and found “conclusive evidence” for contact around 1200 CE, “contemporaneous with the settlement of remote Oceania”.

“Our analyses suggest strongly that a single contact event occurred in eastern Polynesia, before the settlement of Rapa Nui, between Polynesian individuals and a Native American group most closely related to the indigenous inhabitants of present-day Colombia,” they write.

Credit: Ruben Ramos-Mendoza

Previous studies have examined ancient DNA, but this is often degraded, the researchers say. They chose to take a “big data” approach by studying people alive today.

Computational methods allowed them to work out probable genetic ancestry and ancestral geographical origins through studies of gene flow.

They also could distinguish between different modern colonial admixtures; for example, a large French influence in what is known as French Polynesia, and Spanish / Chilean influence in Rapa Nui.

The findings are the latest food for thought in what has been a long and often contentious debate about whether voyaging contact actually happened. There are strong views on both sides and, as the researchers note, previous studies have reached opposing conclusions.

And they acknowledge that they also “cannot discount” an alternative explanation: that a group of Polynesian people voyaged to northern South America and returned together with some Native American individuals, or with Native American admixture.

Nevertheless, they say, they can “show that evidence for early Native American contact is found on widely separated islands across easternmost Polynesia, including islands not influenced by more recent Native American contact events”.

“These spectacular results have major implications for future discussions concerning early migrations and interactions in Polynesia,” notes Paul Waller, from Sweden’s Uppsala University in a related commentary.

From an archaeological viewpoint, he adds, the next step would be to assess how well their model fits with material-culture studies, ethno-historical records, linguistics and evidence of plant and animal distributions.

More pieces to the Polynesian puzzle published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

New timeline rewrites history of Easter Island’s collapse

Easter Island’s prehistoric societal collapse didn’t happen as researchers have long thought, according to a new study.

Researchers have developed a chronology of monument-building and re-examined written observations of early European visitors. With the help of statistics, the research clarifies variable radiocarbon dates pulled from soil under the island’s massive stone platforms topped with megalithic statues and large, cylindrical stone hats.

The new findings indicate that descendants of Polynesian seafarers who settled Rapa Nui, aka Easter Island, in the 13th century continued to build, maintain, and use the monuments for at least 150 years beyond 1600—the date long hailed as the start of societal decline.

“The general thinking has been that the society that Europeans saw when they first showed up was one that had collapsed,” says Robert DiNapoli, who is completing doctoral work in the anthropology department at the University of Oregon. “Our conclusion is that monument-building and investment were still important parts of their lives when these visitors arrived.”

Step-by-step monument building

Easter Island, a Chilean territory, is 1,900 miles from South America and 1,250 miles from other inhabited islands.

By closely examining data from 11 of the sites, the researchers connected radiocarbon dates from previous research to the order of assembly required to build the monuments. A central platform came first. Other sections—crematoriums, burial sites, plazas, statues, and hats—were gradually added. Bayesian statistics were then used to refine the radiocarbon dates and estimate the timing of each these construction events.

Knowing the ordering of dates at a site can help refine radiocarbon dating, which often have a lot of uncertainty, such as large date ranges, DiNapoli says.

“Imagine building something with Lego bricks. You have to do it in a certain order, building over time,” he says. “These monuments also have a necessary order of assembly, and radiocarbon dates from earlier building stages must come before later ones. This information is useful because it allows us to deal with the variability in radiocarbon dates that came from the excavation in a more precise way.”

Monument building, he says, began soon after settlement and increased rapidly, with a steady period of construction continuing beyond the hypothesized collapse and European arrival.

Europeans on Rapa Nui

Dutch travelers in 1722 noted the monuments were in use for rituals and showed no evidence for societal decay. The same was reported in 1770, when Spanish seafarers landed. However, when British explorer James Cook arrived in 1774, he and his crew described an island in crisis, with overturned monuments.

“Once Europeans arrive on the island, there are many documented tragic events due to disease, murder, slave raiding, and other conflicts,” says coauthor Carl Lipo, an anthropologist at Binghamton University. “These events are entirely extrinsic to the islanders and have, undoubtedly, devastating effects. Yet, the Rapa Nui people—following practices that provided them great stability and success over hundreds of years—continue their traditions in the face of tremendous odds.”

The approach developed for the research may be useful for testing hypotheses of societal collapse at other complex sites around the world where similar debates on timing exist, the researchers note.

DiNapoli has been to Rapa Nui several times as a graduate student. “I’ve wanted to be an archaeologist since I was a little kid,” he says. “Rapa Nui was a place I was always interested in. It’s this amazing mystery, of these people who live on a small, isolated island.”

The study appears in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Arizona and the International Archaeological Research Institute in Hawaii. Funding for the work came from the National Science Foundation.

Source: University of Oregon

The post New timeline rewrites history of Easter Island’s collapse appeared first on Futurity.

New timeline rewrites history of Easter Island’s collapse published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes