#Joseph Solis-Mullen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jeffrey Sachs. Photo: Courtesy of Sachs

China Is Not A Threat To The US, But To US Hegemony: US Scholar Jeffrey Sachs

— Global Times | May 22, 2024

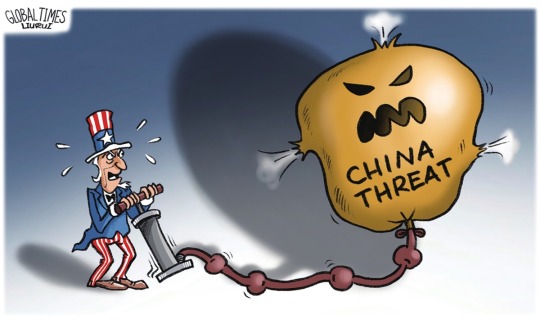

China is not a threat to the US itself, but rather a threat to US hegemony, US scholar Jeffrey Sachs said in a recent interview with Chinese media. He described the US' reaction to China's rise as "neurotic," pointing to publications like Foreign Affairs magazine which constantly discuss how to maintain US superiority over China and spread paranoia about China.

"Basically, what's happening is that China poses a threat to US hegemony. It's not a threat to taking over the US, to you, or to me, but a threat to the claim that the US runs the world," Sachs pointed out.

Sachs emphasized that China is not trying to take over the US and the reason why China is deemed as a threat by the US is because China is showing that it does not run the world the way the US likes to think it does.

In the US nowadays, various versions of "China threat" theories are rampant, revealing a neurotic sense of anxiety about China-related issues among US media and elites. From weather balloons to Chinese corn factories, garlic and cranes, and the recent hype about the so-called overcapacity brought by Chinese electric vehicles, US elites seem fixated on anything that could be perceived as a "China threat" and use this to justify their crackdown on China. This only reveals their anxiety about China's rise and their fear of losing hegemony, analysts believe.

Illustration: Liu Rui/Global Times

Other foreign scholars have also expressed views similar to those of Sachs. "We should not underestimate just how important being No.1 is to America's sense of identity," wrote British scholar Martin Jacques in a column for the Global Times. Jacques argued that for sustaining US hegemony, rather than seeing China as a relatively benign partner, the US instead regards China as a threat to its global primacy and find ways to contain, weaken and undermine it.

"No one country should consider itself leader of the whole world, because we need a world that is diverse, multipolar, and governed not by decisions of one country or the primacy of one country but by international law, especially the UN Charter," said Sachs in a previous interview with the Global Times, urging the US to develop a cooperative relationship with China.

"Right now, we are on a dangerous course. American foreign policy toward China is misguided and a serious mistake," he warned, noting that US politicians have been on a campaign to discredit China and to build an alliance of nations against China, which is obviously a very misguided and dangerous idea.

Joseph Solis-Mullen, A Political Scientist and Economist at the Libertarian Institute, also told the Global Times that the US must learn how to live with and deal with large, powerful states that do not acquiesce to US security prerogatives. "It is up to Americans to start demanding new and better ones, ones geared toward cooperation and the prosperity of all, not attempted global hegemony," he added.

Stephen Roach, a Faculty Member at Yale University and Former Chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, refuted the increasingly rampant "Sinophobia" in the US in an article in the South China Morning Post on March 28. In the article, Roach said, "There is good reason to worry about an increasingly virulent strain of this phobia spinning out of control in the US."

#China 🇨🇳#United States 🇺🇸#US Hegemony#US Scholar | Jeffrey Sachs#Sinophobia#Joseph Solis-Mullen#Stephen Roach

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Reverse the Monetary Breakdown of the West

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Feb 12, 2025

For more than half a century, the global economy has operated under a monetary system divorced from gold. The 1971 collapse of the Bretton Woods system, where the U.S. dollar’s convertibility to gold was suspended, ushered in the fiat money era, a regime in which paper currencies are backed by nothing but government decree. Economist Murray Rothbard, in What Has Government Done to Our Money?, particularly in the chapter “The Monetary Breakdown of the West,” details how this transition has distorted economic incentives, weakened the real economy, and fueled financial speculation at the expense of productive investment.

Today, as inflation erodes purchasing power, debt levels spiral out of control, and economic instability grows, Rothbard’s warnings appear more prescient than ever. The post-1970s monetary settlement has disproportionately benefited financial markets while hollowing out industrial productivity, labor markets, and real wealth creation. A return to the classical gold standard offers a remedy: restoring monetary discipline, curbing government excess, and aligning financial activity with real economic production.

Under the classical gold standard, which prevailed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, money had intrinsic value. Gold-backed currencies prevented governments from inflating the money supply arbitrarily, ensuring stable purchasing power, encouraging long-term investment, and easing cross-border investment.

Bretton Woods, established in the aftermath of World War II, was a scarcely satisfactory compromise: though the system maintained a nominal link to gold, it allowed central banks more discretion over monetary policy. As Rothbard chronicles, this system was inherently unstable. Governments, especially the United States, pursued expansionary fiscal and monetary policies that ran counter to the constraints of a gold-backed system.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

[Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the May/June 1955 issue of Faith and Freedom under Rothbard’s pseudonym, Aubrey Herbert. Rothbard is responding to an article by the Buckleyite conservative Willi Schlamm who advocates for military intervention against China. The Schlamm article is printed in full at the bottom of this page. Rothbard, of course, takes the opposite view of Schlamm, condemning preventive war, conscription, and Schlamm’s apparent desire to immediately resort to full-blown war. (Thanks to Joseph Solis-Mullen for finding and transcribing these articles.)] The publication of Mr. Schlamm’s criticism is, I believe, a healthy development. For it reflects a deep-rooted split within … Continue reading →

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

China Won't Be Taking Over the World | Joseph Solis-Mullen via /r/China

China Won't Be Taking Over the World | Joseph Solis-Mullen https://ift.tt/3jDYAdq Submitted August 11, 2021 at 07:26AM by UrbanAbsconder via reddit https://ift.tt/3CD3U9y

0 notes

Text

Against the Tyranny of Urban Majorities

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Nov 26, 2024

In a recent and rather surprising piece, The Wall Street Journal highlighted growing frustrations among rural residents of states like Illinois, solidly Republican regions who feel disenfranchised by the political dominance of urban metropolises like Chicago and the wider Cook County. The article described sentiments among rural Illinoisans who increasingly view their state government as an unrepresentative body, one that governs in the interests of urban elites while neglecting or outright opposing the values, interests, and livelihoods of those living in less densely populated areas.

This frustration is not unique to Illinois; it resonates in states like California, Oregon, and New York, where rural and small-town residents feel marginalized by overwhelmingly urban legislatures and policies crafted by political majorities in the cities. It raises an important question: why should sparsely populated regions be bound indefinitely to the political dominance of a few, highly concentrated urban areas?

The idea that rural regions might seek autonomy from urban majorities has an intuitive appeal, especially when considering the arbitrary nature of state boundaries in the United States. Unlike France, England, or other nations rooted in medieval kingdoms and centuries-old cultural identities, states like Illinois and California are constructs of relatively recent history, products of political compromises and expedient geographic delineations. Many boundaries of these states reflect no natural or inherent connection among their inhabitants. This arbitrariness invites comparisons to the imperial cartography of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, where colonial powers carved up Africa and the Middle East into artificial nations that still grapple with the consequences of their incoherent borders. Why, then, should we expect places as disparate as Chicago and rural Illinois, or San Francisco and the farmlands of California’s Central Valley, to share common governance without conflict or resentment?

The argument for rural secession from urban-dominated states rests on several principles. First, it is fundamentally undemocratic to force people into perpetual political subjugation because they happen to live within arbitrarily drawn borders. Unlike democracy, properly republican government depends not just on majority rule but on the protection of minority rights, including the right to self-governance. When rural communities are systematically outvoted and overruled by urban majorities, they are effectively disenfranchised within their own states.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reintroducing Liberty’s Master Historian

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Jan 7, 2025

On June 1, 1983, at a morning session of the Cato Institute Summer Seminar, attendees bore witness to what remains to this day one of the greatest single revisionist retellings of the tragic and formative period of world history: 1914-1945.

For three hours, Dr. Ralph Raico held forth, touching on every relevant subject to the horrible thirty years of war that gave rise to communism, Nazism, nuclear bombs, the Cold War, and the all powerful state. He expertly tied together the decline of classical liberalism in the late nineteenth century and the rise of statism, the formation and growth of rigid military blocs, the armaments race and early military industrial complexes of the powers, mass propaganda, government duplicity, total war, and mass death.

It is truly a work of the absolute first order, and a necessary watch for any interested critic of government narratives surrounding the two world wars.

Now, in a great favor to all those so concerned, Edward W. Fuller and the Mises Institute have put Raico’s great lecture into print.

Not only does this amplify its reach, reigniting interest in Raico’s classic lecture and offering a new medium of consumption, the book includes the invaluable addition of footnotes corresponding to the many references to authors and works which Raico makes throughout the lecture—as well as judiciously inserted clarificatory commentary by Fuller where necessary.

In addition to the carefully curated transcription of Raico’s original lecture, Fuller includes an excellent biography of the man himself, from Raico’s upbringing in New York, where attended lectures by Ludwig von Mises and befriended Murray Rothbard, to his time as a PhD student under Friedrich von Hayek, his involvement in major academic journals (from the New Individualist Review, The Libertarian Forum, and still extant Journal of Libertarian Studies) to his finally settling down to a professorship at Buffalo State College.

Raico was, as Fuller rightly states in his Introduction, one of the greatest classical-liberal historians of all time. His work on classical liberalism in France and Germany remains groundbreaking, and his critique of the supposedly “great leaders” students are taught to venerate, like Truman and Churchill, cuts through statist lies with enviable clarity and precision, revealing these men to be duplicitous opportunists and responsible for a great deal of unnecessary death and destruction besides.

0 notes

Text

America’s Origins of Russophobia

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Dec 18, 2024

For those that grew up in the United States in the 1990s and 2000s, the explosion of Russophobia over the past decade likely came as something of a surprise. A brief survey of the history of Russophobia, however, reveals that the decade and a half after the end of the Cold War was something of an anomaly in the past century and a half of American foreign policy, with a blend of inherited geopolitical fears and ideological tensions leading to a generally anti-Russian sentiment in Washington.

Our investigation begins with the so-called “Testament of Peter the Great.” An eighteenth century forgery of largely Polish origin, it purported to show, in the words of the University of London historian Orlando Figes, that the aims of Russian foreign policy were nothing less than world domination:

“…to expand on the Baltic and Black seas, to ally with the Austrians to expel the Turks from Europe, to conquer the Levant and control the trade to the Indies, to sow dissent and confusion in Europe and become the master of the European continent.”

First published in Napoleonic France in 1812, on the eve of the Grand Armée’s ill-fated invasion of Russia, it was to go on to provide the grist for many an English fear-monger’s mill.

In 1817, Sir Robert Wilson’s A Sketch of the Military and Political Power of Russia in the Year 1817 luridly detailed the military and geopolitical threat supposedly posed by Russia, and a decade later George de Lacy Evans’s On the Designs of Russia repeated these earlier warnings—both were favorably received by the public and among the ruling establishment, paranoid as ever about any potential threat to British control of India. Then, in 1834, the highly influential David Urquhart published his own pamphlet, England, France, Russia and Turkey, casting Russia as the perpetual antagonist to British interests in the Near East and Central Asia.

Not everyone was fooled, however. As noted by the Mises Institute’s Ryan McMaken, the great British liberals, such as Richard Cobden and John Bright, often opposed these characterizations and exaggerated threats. In turn, they were rewarded only with the scorn familiar to today’s scoffers. Indeed, the perception of Russia as a natural, age-old enemy became embedded in British geopolitical thought.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ignoring China’s Redlines Could Make Taiwan the Next Ukraine

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Dec 5, 2024

The recent meeting between outgoing U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping in Lima, Peru offered a stark illustration of the divergent priorities and perspectives shaping the fraught U.S.-China relationship. While the Biden administration’s statement on the meeting emphasized “responsibly managing competition” and highlighted areas of potential cooperation, Xi took the opportunity to reiterate China’s concerns over American actions that Beijing views as infringements on its four “red lines.”

These contrasts underscore the urgent need for Washington to reevaluate its approach toward Beijing—the impression, strongly given, is that Washington is ignoring Beijing’s complaints, trying instead to force discussion onto issues it feels willing to work with Beijing on. But the current strategy, marked by a mix of competitive posturing, efforts at military and economic containment, and selective moralizing risks perpetuating unnecessary tensions, increasing the likelihood of miscalculation, and ignores clear lessons from recent history.

To start with, for Beijing issues like the status of Taiwan remain non-negotiable, with Xi expressing particular frustration over what he described as a pattern of U.S. inconsistency—“saying one thing and doing another,” vis a vis the so-called “One China Policy.”

But it is on that point, the single most difficult point of the relationship going all the way back to normalization, that the United States doubled down, defending high-level visits, continued arms sales, and naval patrols in the Strait.

U.S. Navy “freedom of navigation” operations in and around the Taiwan Strait, which Washington frames as essential to upholding international law, can easily be seen from Beijing’s perspective as provocative and disrespectful of its territorial claims and sovereignty. To understand this, consider a hypothetical scenario: Chinese warships conducting similar exercises near the Florida Keys, or elsewhere in the eighty odd miles of sea between Florida and Cuba. The outcry in Washington, and likely around the country, would be immediate and severe.

That aside, there is also the increasing chance of a dangerous encounter at sea, particularly in the South China Sea, that could inadvertently spark a showdown neither Washington nor Beijing will feel able to back down from—which would, to put it mildly, be highly undesirable.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Whether the Interest Rate Rises or Falls, Inflation Is Here to Stay

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Nov 21, 2024

In an economic landscape shaped by the aggressively rising prices of 2020-2022, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy pendulum swung dramatically. Starting from rock bottom rates, it engaged in a series of hikes the likes of which had not been seen since the early 1980s, moving from less than 1% in February 2022 to over 4% a year later. Going still higher with rates above 5% by the end of 2023, the Federal Reserve held rates there for the first half of 2024 in an attempt to bring the Consumer Price Index (CPI), one of its preferred price gauges, down from the scorching 9% peak in the summer of 2022.

Under pressure from Wall Street to the Treasury, both of whom have become dependent on cheap borrowing, to start cutting interest rates as quickly as possible once the annualized rate of price growth neared the desired 2% target, the Fed began easing rates in September.

However, this cutting cycle, anticipated by reacceleration of money supply growth starting in January 2024, coupled with broader economic dynamics, has coincided with a reacceleration of price levels, raising questions about the durability of the Fed’s “victory,” particularly in conjunction with some of the economic policies being floated by Donald Trump for his second term that could lead to massive upward pressures on prices.

Indeed, recent data suggests the price level is inching back up. In October, the CPI rose to 2.6% annually, marking the first increase in headline inflation in seven months. Meanwhile, core inflation—a measure that excludes volatile food and energy prices—has risen at an annualized pace of 3.4% to 3.8% for three consecutive months, signaling persistent underlying price pressures.

Some of these pressures stem from the same structural issues that drove price increases during the pandemic years. Housing costs, which contributed significantly to the recent uptick, remain elevated despite softening rents for new leases. Median home prices have surged 30% since early 2020, leaving Americans to shoulder higher mortgage payments and rents. Food and energy prices have also remained stubbornly high, with egg prices nearly doubling since pre-pandemic times and gasoline costs up 16%.

This resurgence underscores a critical reality: while the pace of the increase of the price level may have “slowed,” prices remain substantially higher than their pre-pandemic levels. Consumers, therefore, continue to feel the squeeze, even as wage growth outpaces inflation. This is a dynamic that Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has cautiously acknowledged as insufficient to reignite significant inflationary pressures on its own, though a wage-price dynamic is far from out of the question as the labor market remains historically tight in the face of large generational turnover.

Precedent, particularly that of the 1970s, demonstrates that loosening monetary policy before the price level is firmly anchored can lead to renewed price surges. October’s data aligns with these warnings, showing how even modest economic shifts can push the price level higher.

0 notes

Text

The (Predictable) Defeat of Moderate Reforms

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Nov 14, 2024

In the 2024 general election, several states and cities across the country put forth initiatives aimed at adopting ranked-choice voting (RCV) and nonpartisan primaries. These measures were promoted as essential steps in reducing political polarization, creating more representative elections, and empowering independent and moderate voices. However, results showed a significant resistance to change, as most RCV initiatives failed at the statewide level, with the only notable success coming from Washington DC, which passed both open primaries and RCV.

The outcome reveals substantial challenges in advancing election reform, despite growing public dissatisfaction with the current two-party political system. This article examines what happened, explores the concept of ranked choice voting, and considers why it remains a promising tool for disrupting the duopoly of American politics.

Ranked-choice voting allows voters to rank candidates by preference rather than selecting only one. In an RCV election, if no candidate achieves a majority of first-choice votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Voters who selected the eliminated candidate as their first choice then have their votes transferred to their second choice. This process continues until a candidate secures a majority, making RCV a more comprehensive reflection of voter preferences.

Statewide RCV measures were voted down in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and South Dakota. Each of those states had proposed initiatives that would either replace party primaries with nonpartisan contests, implement RCV for general elections, or both. Advocates for these reforms argued that they would curb the extreme partisanship of current U.S. politics by encouraging candidates to appeal to a broader range of voters. Despite these efforts, the measures faced fierce opposition from both major political parties, who argued that these reforms would confuse voters and weaken party control over the candidate selection process.

The pushback was especially intense in highly polarized states, where suspicion of any changes to the voting system ran high. As Nick Troiano, executive director of Unite America, explained, “Any change to election rules in this highly polarized time will be met with skepticism by voters who will more often than not default to ‘no.’”

0 notes

Text

Case Study, Taiwan: A Nation is the Story We Tell Ourselves

by Joseph Solis-Mullen | Oct 17, 2024

In his famous 1882 lecture “What is a Nation?” the French historian and philosopher Ernest Renan emphasized the role of collective memory and even fictitious or selective historical narratives in the creation and maintenance of national identity, writing “Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation.”

What Renan was arguing is that nations are built not only on shared history but also on the myths and selective memories that bind people together. This selective forgetting often involves downplaying or erasing divisive events or highlighting certain aspects of a past to create a sense of unity and continuity. Even if that narrative isn’t entirely historically accurate, that isn’t the point. This selective memory allows a state or nation to foster a sense of unity and purpose among its citizens.

This past Thursday Taiwan’s President, Lai Ching-te, gave a highly anticipated speech on the occasion of Taiwan’s “National Day” celebrations—and Renan could hardly have been more impressed.

As one might expect of such a speech, Lai’s first on this occasion since taking office, it was full of paeans to the greatness of the state and its people, as well as the kind of dubious historical assertions, the nationalist myths, that everywhere buttress state power.

For example, Lai connected the current government on Taiwan to those presumably brave heroes who over a century ago “rose in revolt and overthrew the imperial regime,” with the intent to “establish a democratic republic of the people, to be governed by the people and for the people.” Naturally, Lai neglected to mention that the actors in question were a combination of ambivalent bureaucrats, ambitious warlords, opportunistic gangsters, and disaffected intellectuals who quickly fell to usurping and warring with one another.

0 notes

Text

DON’T CONFUSE THE FALKLAND ISLANDS FOR TAIWAN

— By Joseph Solis-Mullen | October 13, 2021 | The Libertarian Institute

Though the conflict is little known in the United States, Chinese military planners have long obsessed over what lessons can be gained from studying the brief 1982 conflict between Argentina and Great Britain over the small collection of islands in the South Atlantic near the tip of South America—the Falklands—and for good reason. Its location, historical context, and the nature of the conflict between the powers involved more closely mirror the current standoff over Taiwan than any other example in modern war. Drawing lessons from history is a tricky business, however. And while Chinese military planners do well in studying the tactics of the conflict, U.S. foreign policy architects should be far more cautious. As will be presented below, presuming that by doing the opposite of what the British did in the case of the Falklands War that conflict will be averted or made less likely is not borne out in a comparison with the situation over Taiwan.

A hardscrabble collection of over seven hundred small islands, the largest and most predominant among them West and East Falkland, the Falklands lay less just nine hundred miles from the Antarctic circle and were uninhabited when the first European explorers began probing the southern cone of South America. Though the Spanish, English, and French all made various claims to the islands during the seventeenth century, by the eighteenth century Great Britain, with its superb navy, had proven most able to enforce its writ and had claimed sole possession of the islands as early as 1774. The outbreak of the French Revolution and later the Napoleonic wars, however, meant no one was home when the recently liberated Buenos Aires elites decided to stake a claim of their own and assert full authority—the islands being, after all, just three hundred miles out to sea. And so it was from 1816-1832 the islands were under Argentina’s control.

The British returned, however, and after a brief battle drove the Argentinians from the islands, in 1840 making them Crown colonies. With Britain ascendent and on its way to controlling, at its apogee, fully 25% of earth’s landed surface, Buenos Aires could do little but grumble bitterly. But here are the origins of the competing claims to the Falkland islands; claims that would continue to be disputed at a low diplomatic level at varying degrees of intensity over the next century and a half.

Fast forward to the second half of the twentieth century, with Great Britain exhausted by two world wars, its empire crumbling, revolting, or being otherwise abandoned, the Labor governments of the 1960s proved receptive to Peron’s more aggressive reassertions of Argentina’s claims over the islands. Discussions were slow, however, dragging on into the 1970s unresolved—hampered in large part by existing commercial interests on the islands and by a perception among U.K. voters of the essential Britishness of the Falklanders as part of “Greater Britain,” sharing a common language, culture, way of life, and other customs.

Economic realities were such, however, that by the late 1970s Great Britain had all but ceased involvement in the South Atlantic region and scrapped its only ship devoted to patrolling the area without replacing it. Having, then, in the years preceding the conflict, signaled a willingness to at least allow for the Falklands to fall into the Argentinian orbit, and then neglecting to maintain a forceful and visible presence, it is generally undisputed that the military junta that had seized power in Argentina in 1976 believed Thatcher’s government would do nothing were it to move to reclaim the islands. Therefore, facing rapidly declining popularity in the face of economic mismanagement, the junta decided the best way to offset the growing social unrest was a nice, short patriotic war in defense of a long-besmirched national honor.

Reasonable though this line of thinking was, it was all based on the premise that the U.K. leadership would not go to war over the Falklands: and this turned out to be a mistake.

For though the junta were correct that the British had been signaling apparent ambiguity regarding the fate of the islands, that they were completely unimportant militarily and economically to the home island. But what the Junta failed to understand was how their actions would impact the political incentive structure facing the embattled Thatcher government. Unpopular and struggling, whatever Thatcher’s actual feelings towards the Falklands, an election was just around the corner and the press and popular opinion made it impossible for her to do anything other than fight in defense of what was left of the empire. After being assured by the British military establishment that the islands could be retaken, Thatcher ordered a task force assembled and dispatched.

And so the war came.

As innumerable books on the play-by-play of the military conflict describe—many of which were authored by participants in the events on the ground—even though the Argentinian armed forces were something close to a joke, its soldiers under-trained raw conscripts, and its military hardware equally substandard, the campaign was very nearly a disaster for Great Britain. They were unaccustomed by now to projecting force, and needed civilian ships to serve as transports. Approaching the occupied islands, the Royal Navy lost multiple ships to airstrikes launched from the mainland in the form of sorties, as well as Exocet missiles in the week and a half it took the British to both establish dominance of the surrounding sea and land significant numbers of troops. They ultimately succeeded in doing so after the Argentinian navy and air force abandoned the islands. Their comrades, now marooned, were left to face the British special forces alone. The rugged terrain meant the series of sporadic engagements that followed were of the running sort—with only a few pitched battles in all—and Great Britain retook the islands just 74 days after the Argentinian forces had invaded.

In short order the junta was overthrown, Thatcher was reelected, and the Falklands remained inside the British sphere.

In the case of the Falklands, it is almost certain that had Great Britain made its intention to defend the islands clear ahead of time the Argentinian junta would not have invaded. At the time, then-Senator Joe Biden was among the most vocal supporters of British military intervention. As a close observer of the conflict, and with a hawkish foreign policy team behind him, the lesson the Biden administration seems to have drawn as applied to Taiwan is that by making its intentions clear it will thereby avoid conflict with China. This shift away from the prior tactic of “strategic ambiguity” was evidenced by Biden’s statements following the botched Afghanistan pullout. Speaking to reporters about whether or not allies could still count on American security guarantees, Biden included Taiwan on a list that included the NATO countries and Japan.

The evidence suggests Biden is quite serious about this commitment. From the immediate high-level meetings between his administration and the countries of the QUAD, arming the Australians with submarines capable of snooping for long periods in China’s backyard, and arms sales to Taiwan, the message couldn’t be clearer: we’ll fight you so don’t even try. Key differences between the Falklands and Taiwan, however, cast serious doubt on this shift in tactics.

First, Argentina’s military hadn’t planned for a British counter-attack while the Chinese most certainly will have.

Second, Taiwan is much closer to mainland China and its missile batteries and airfields than were the Falklands to Argentina. Furthermore, the missiles China would be launching at American, Japanese, Indian, and Australian forces would be satellite guided and far more accurate and deadly.

Third, it is China that has the territorial claim and grievance. Granted, Beijing’s claim on the island is questionable, as it hasn’t been ruled by Beijing in over a century and was only added to the Chinese Empire in the late eighteenth century. But all that aside, it isn’t recognized by the international community as an entity outside China proper.

Fifth, the Argentinian population weren’t committed to a fight over the Falklands in the same way the Chinese are to Taiwan.

Sixth and finally, the Argentinian junta needed the signal of ambiguity from Great Britain because they rightly suspected they couldn’t stand up to it in a fight. China does not feel that way—if anything U.S. belligerence only serves to provoke a proud Chinese government and people into aggressive action in defense of their honor. Afterall, it isn’t a secret that in CCP propaganda Taiwan represents the final remnant of the “century of humiliations.”

In short, Biden’s shift in tactics from strategic ambiguity to a policy of strategic clarity represents a misapplying of the lessons of history. Doing what would have prevented a similar conflict in the past is no guarantee of success in the here and now. If U.S. strategy is aimed at maintaining peace in the region, its change in tactics seem likely only to undermine it.

— Joseph Solis-Mullen is a graduate of both Spring Arbor University and the University of Illinois, and is a current graduate student in the Department of Economics at the University of Missouri. An author, blogger, and political scientist, his work can be found at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Sage Advance, Seeking Alpha, and his personal website. You may contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter.

0 notes