#John Maloof

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

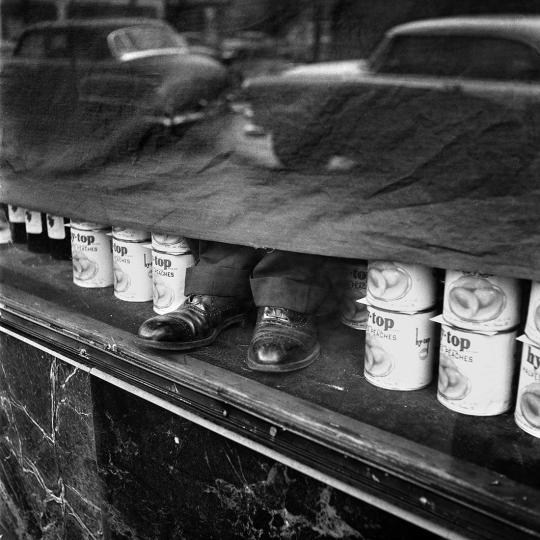

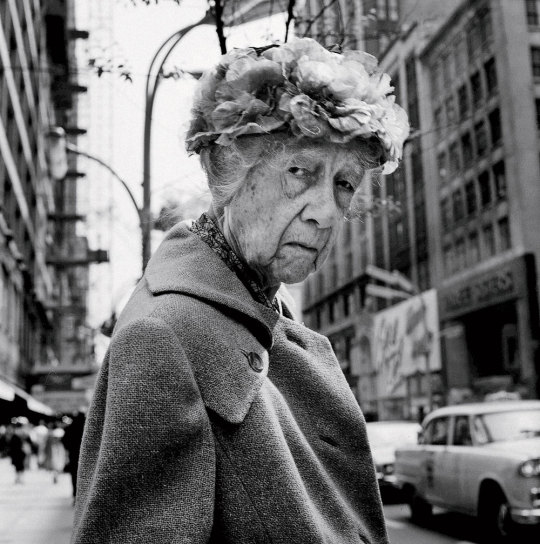

Vivian Maier - Chicago, 1978.

#vivian maier#chicago#1978#photography#street photography#street photoshoot#dorothea lange#saul leiter#elliott erwitt#ilse bing#Dorothea Lange#black and white photography#vintage photography#gordon parks#Finding Vivian Maier#john maloof#spinster#GOAT#mary poppins#robert frank#diane arbus#Rolleiflex#b&w photography#b&w aesthetic#b&w

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The negative is comparable to the composer's score, and the print to its performance.

Ansel Adams, quoted in Viviane Maier: A Photographer Found, by John Maloof and Marvin Heiferman

#ansel adams#quotes#quotes about photography#film photography#printmaking#john maloof#marvin heiferman#vivian maier#books about photography

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes we are unaware of the people around us. Now and then, they reappear unexpectedly. That is the case with Vivian Maier. This book, by John Maloof and the Howard Greenberg Gallery, contains an exceptional collection of Maier's photography. She passed away in 2009, and her work was all but unknown during her lifetime. This book was first published by Harper Design in 2014. Meanwhile, When the Gods Are Silent, by Mikhail Soloviev, which made an appearance in one of Maier's photos from 1954, can still be found in bookstores such as Aziraphale's Books.

#Viviane Maier#Street Photography#Photographers#Aziraphale's Books#Viviane Maier A Photographer Found#John Maloof#Howard Greenburg#Marvin Heiferman#Harper Design#2015#when the Gods are Silent#Mikhail Soloviev#Popular Library#1954#bookstores#bookshops#photography books

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canada. Undated. (c) Estate of Vivian Meyer. John Maloof Collection.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

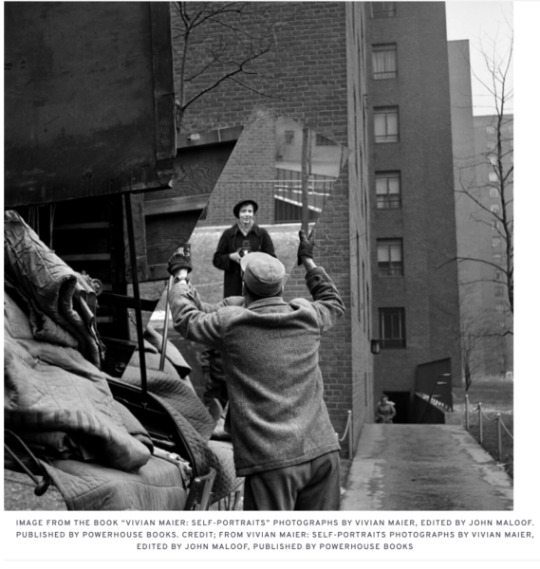

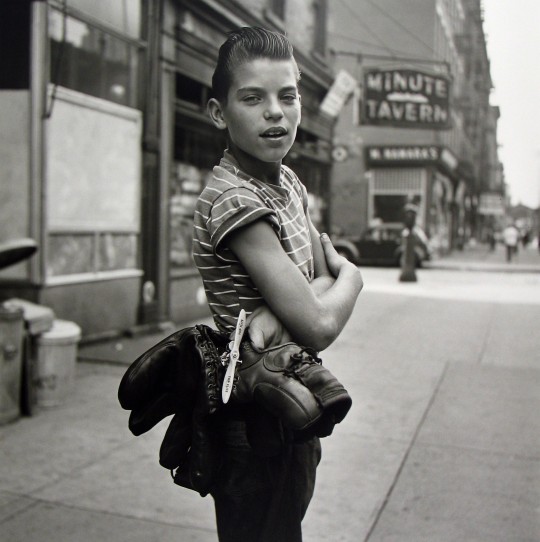

Vivian Maier. John Maloof Collection, October 18, 1953, New York City.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet Vivian Maier, the Reclusive Nanny Who Secretly Became One of the Best Street Photographers of the 20th Century

The self-taught artist is getting her first museum exhibition in New York City, where she nurtured her nascent interest in photography.

Vivian Maier took more than 150,000 photographs as she scoured the streets of New York and Chicago. She rarely looked at them; often, she didn’t even develop the negatives. Without any formal training, she created a sprawling body of work that demonstrated a wholly original way of looking at the world. Today, she is considered one of the best street photographers of the 20th century.

Maier’s photos provide audiences with a tantalizing peek behind the curtain into a remarkable mind. But she never intended to have an audience. A nanny by trade, she rarely showed anyone her prints. In her final years, she stashed five decades of work in storage lockers, which she eventually stopped paying for. Their contents went to auction in 2007.

Many of Maier’s photos ended up with amateur historian John Maloof, who purchased 30,000 negatives for about $400. In the years that followed, he sought out other collectors who had purchased boxes from the same lockers. He didn’t learn the photographer’s identity until 2009, when he found her name scrawled on an envelope among the negatives. A quick Google search revealed that Maier had died just a few days earlier. Uncertain of how to proceed, Maloof started posting her images online.

“I guess my question is, what do I do with this stuff?” he wrote in a Flickr post. “Is this type of work worthy of exhibitions, a book? Or do bodies of work like this come up often? Any direction would be great.”

Maier quickly became a sensation. Everyone wanted to know about the recluse who had so adeptly captured 20th-century America. Her life and work have since been the subject of a best-selling book, a documentary and exhibitions around the world.

Now, the self-taught photographer is headlining her first major American retrospective. “Vivian Maier: Unseen Work,” which is currently on view at Fotografiska New York, features some 230 pieces from the 1950s through the 1990s, including black-and-white and color photos, vintage and modern prints, films, and sound recordings. The show is also billed as the first museum exhibition in Maier’s hometown, the city where she nurtured her nascent interest in photography.

Born in New York City in 1926, Maier grew up mostly in France, where she began experimenting with a Kodak Brownie, an affordable early camera designed for amateurs. After returning to New York in 1951, she purchased a Rolleiflex, a high-end camera held at the waist, and began developing her signature style: images of everyday life framed with a stark humor and intuitive understanding of human emotion. She started working as a governess, a role that allowed her to spend hours wandering the city, children in tow, as she snapped away.

She left New York about five years later, when she secured a job as a nanny for three boys—John, Lane and Matthew Gensburg—in the Chicago suburbs. The family was devoted to Maier, though they knew very little about her. The boys remember attending art films and picking wild strawberries as her charges, but they don’t recall her ever mentioning any family or friends. Their parents knew that Maier traveled—they would hire a replacement nanny in her absence—but they didn’t know where she went.

“You really wouldn’t ask her about it at all,” Nancy Gensburg, the boys’ mother, told Chicago magazine in 2010. “I mean, you could, but she was private. Period.”

Despite Maier’s reclusive tendencies, the Gensburgs knew about her photography. It would have been difficult to hide. After all, she lived with the family and had a private bathroom, which she used as a darkroom to develop black-and-white photos herself. The Gensburgs frequently witnessed her taking photos; on rare occasions, she even showed them her prints.

Maier stayed with the Gensburgs until the early 1970s, when the boys were too old for a nanny. She spent the next few decades working in other caretaking roles, though she doesn’t appear to have developed a similar relationship with these families, who viewed her as a competent caregiver with an eccentric personality. Most never saw her prints, though they do remember her moving into their homes with hundreds of boxes of photos in tow.

“I once saw her taking a picture inside a refuse can,” talk show host Phil Donahue, who employed Maier as a nanny for less than a year, told Chicago magazine. “I never remotely thought that what she was doing would have some special artistic value.”

Meanwhile, the Gensburgs kept in touch. As Maier grew older, they took care of her, eventually moving her to a nursing home. They never knew about the storage lockers. When she died at age 83, a short obituary appeared in the Chicago Tribune, describing her as a “second mother” to the three boys, a “free and kindred spirit,” and a “movie critic and photographer extraordinaire.”

Maier’s mysterious backstory is a large part of her present-day appeal. Fans are captivated by the photos, but they’re also intrigued by the reclusive nanny who developed her talents in secret. “Vivian Maier the mystery, the discovery and the work—those three parts together are difficult to separate,” Anne Morin, curator of the new exhibition, tells CNN.

The show is meant to focus on the work rather than the mystery. As Morin says to the Art Newspaper, she hopes to avoid “imposing an overexposed interpretation of her character.” Instead, the exhibition aims to elevate Maier’s name to the level of other famous street photographers—such as Robert Frank and Diane Arbus—and take on the daunting task of examining her large oeuvre.

“In ten years, we could do another completely different show,” Morin tells CNN. “She has more than enough material to bring to the table.”

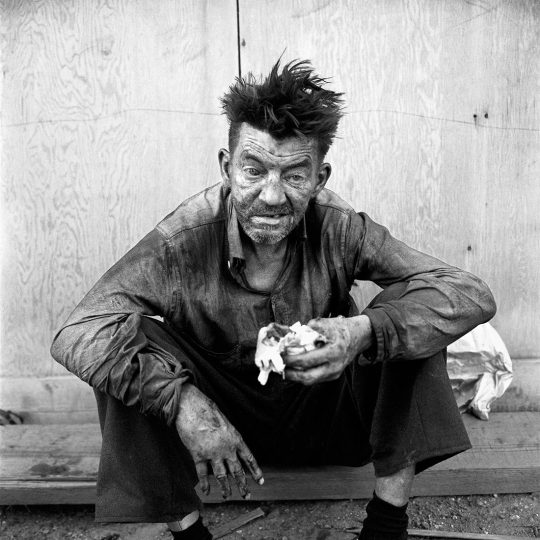

The subjects of Maier’s street photos ran the gamut, but she often turned her lens toward “people on the margins of society who weren’t usually photographed and of whom images were rarely published,” per a statement from Fotografiska New York. The Gensburg boys recall her taking them all over the city, adamant that they witness what life was like beyond the confines of their affluent suburb.

The exhibition is organized thematically, with sections devoted to Maier’s famous street photos, her experimental abstract compositions and her stylized self-portraits. The self-portraits, which frequently incorporate mirrors and reflections, amplify her enigmatic qualities, usually showing her with a deadpan, focused expression. Her voice can be heard in numerous audio recordings, which play throughout the exhibition. As such, even as the show focuses on the work, Maier the person is still a frequent presence in it.

“The paradox of Vivian Maier is that the lifetime of anonymity that has captured the public imagination persists in the work,” writes art critic Arthur Lubow for the New York Times, adding, “An artist uses a camera as a tool of self-expression. Maier was a supremely gifted chameleon. After immersing myself in her work, other than detecting a certain wryness, I could not get much sense of her sensibility.”

The artist undoubtedly possessed a curiosity about her immediate surroundings, which she photographed with a “lack of self-consciousness,” Sophie Wright, the New York museum’s director, tells CNN. “There’s no audience in mind.” There is no evidence that Maier wondered about her viewers—or that she ever imagined having viewers in the first place. They, however, will never stop wondering about her.

~ Ellen Wexler, Assistant Editor, Humanities · July 9, 2024.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian leader knows he is in the driver's seat in Ukraine, one expert says

Dec 20, 2024

Russian President Vladimir Putin was confident during his annual “Direct Line press event” when he spoke about his latest hypersonic missile, the Oreshnik, and essentially called it unstoppable once launched.

He even half-jokingly called for a duel with the West.

“There is no chance of shooting down these missiles,” he said, according to RT.

He responded to a question about Western experts who questioned possible vulnerabilities and recommended “some kind of technological experiment.”

“Let’s say a high-tech duel of the 21st century,” he said. “Let them determine some kind of strike target, say, in Kyiv. They’ll concentrate all of their air defense and missile defense forces there, and we’ll strike there with the Oreshnik. And we’ll see what happens.”

Michael Maloof, a former senior security policy analyst at the Pentagon, spoke to Sputnik and said the U.S. has nothing in its arsenal that can stop the medium-range hypersonic ballistic missile.

“The US not only does not have a hypersonic offensive system, it doesn't even have a defensive system that has any hope of stopping Oreshnik and the new class of missiles that are coming out,” he told the outlet.

Professor John Mearsheimer, the University of Chicago professor, told Judge Andrew Napolitano’s “Judging Freedom” that Putin was being “playful” in his response because “he is in the driver’s seat.”

“He knows that we are in deep trouble in Ukraine,” the professor said. “And he knows the Oreshnik missile is going to get through no matter what, and, therefore, he can poke us in the eye.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vivian Maier (US, 1926 - 2009)

Self-Portrait, 1955

Short bio of wonder [edited]

American of French and Austro-Hungarian extraction, intensely guarded and private, decidedly unmaterialistic (money-wise), Vivian would amass found items, art books, newspaper clippings, home films and thankfully her negatives. She recorded the 2nd 1\2 of the 20th c. Urban America, creating masterpieces of Street Photography.

Maier would leave behind over 100,000 negatives and a series of homemade documentary films and audio recordings.

Having picked up photography in Europe 2 years earlier, came back to New York City in 1951, where she would comb the streets. In 1956 Vivian left for Chicago, where she’d spend most of the rest of her life working as a Nanny and “quietly” taking pictures.

Her first camera was a modest Kodak Brownie (one shutter speed, no aperture and focus control) soon to be replaced in 1952 by her first (of many) Rolleiflex. She later also used a Leica IIIc, an Ihagee Exakta, a Zeiss Contarex and various other SLR cameras.

Maier’s massive body of work would come to light when in 2007 at a local thrift auction house on Chicago’s Northwest Side. John Maloof discovered, championed and archived her work. Now, with roughly 90% of her work reconstructed and cataloged, it's available to the public.

https://www.vivianmaier.com/gallery/self-portraits/#slide-13

https://www.vivianmaier.com/about-vivian-maier/

#Vivian Maier#Street Photography#masterpiece#self portrait#mirror#odd#secret#nunny#history#story#found objects

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read in September of 2023

Nights of Plague by Orhan Pamuk. Fiction: historical. A fictional island in the Ottoman Empire inhabited by a Muslim and Greek Orthodox population is left to fend for itself after a plague becomes uncontrollable. This book was long and intricate. Despite the historical setting, the dysfunctional government and religious conflict exacerbating the damage of a plague felt a little too close ot home.

The Confessions of St Augustine. Nonfiction: autobiographical, religious. Augustine's life story and theology. A lot more about time than I would've expected. Sometimes I think he's overdramatic or unhelpful, but then sometimes I'm amazed at his devotion and love for God. Augustine is early enough and influential enough that he's probably going to be vaguely relevant to my studies at some point, so it made sense to read the Confessions.

When We Were Sisters by Fatimah Asghar. Fiction: contemporary, maybe a bit of poetry? This book tells the story of three orphaned sisters who have to make a life for themselves, under the neglect and abuse of their guardian uncle, negotiating issues like the immigration status of their family members, gender and sexuality, and living as Muslims when their access to Muslim community is restricted.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa. Fiction: speculative, dystopian. On an island where things keep disappearing, people who don't forget the disappearing items face persecution from their government. As life gets bleaker and more mundane, the characters of this book resist in small, subtle bursts of color and joy.

Where Reason Ends by Yiyun Li. Fiction: autobiographical, contemporary. A mother has a conversation with her dead teenage son after he commits suicide.

The Age of Wood by Roland Ennos. Nonfiction: history, nature. This book traces how wood has been used throughout history. This book paired well with Teaching the Trees by Joan Maloof, which I read earlier this year.

The Blue Castle by Lucy Maud Montgomery. Fiction: romance. When a 29-year-old woman is told that she only has a year to live, she decides to defy her relatives' expectations and live on her own terms. I found Valancy so deeply relatable that it was a delight to see her crafting the life she wanted. The plot twists in this book are ah... big and melodramatic. I don't think this is LMM's tightest work from a craft perspective, but it was a really enjoyable book and I'd recommend it to my fellow lonely spinsters (with the caveat that it is a romance :/ )

Kibogo by Scholastique Mukasonga. Fiction: historical, contemporary, postcolonial. This book follows a Rwandan village through several generations of religious developments in response to Christian missionaries. This book is critical of missionary colonization in ways that are similar to Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe or The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver. I thought the various ways in which characters made sense of Christianity in light of their largely banned yet profoundly present preexisting belief stories was really remarkable.

Oranges by John McPhee. Nonfiction: agriculture, travel. There was a lot of fascinating information about how oranges get to consumers, albeit probably a few decades out of date.

No god but God by Reza Aslan. Nonfiction: history, religion. This book traces the origins and history of Islam. It was published in 2009 and does make some conscious effort to be an apologetic for Islam to a hostile post-911 society. This is one of the books I'm reading to make up for the Islam in America class I had to drop from this semester.

The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri. Fiction: contemporary. When their newborn son's prospective name is lost in the mail, a Desi couple living in New England resort to naming him after Russian author Nikolai Gogol, a decision that shapes the trajectory of their son's life.

When I Was a Child I Read Books by Marilynne Robinson. Nonfiction: religion, sociology, economics. This is a collection of essays. I really appreciate the way Marilynne Robinson writes about the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible. I highly recommend this book for Christians who would like to avoid inadvertent antisemitism.

Bee Season by Myla Goldberg. Fiction: contemporary, speculative? This book follows a loving but dysfunctional family of four, each of whom wrestles with religious identity and purpose. There are spelling bees, kaleidoscopes, Jewish mysticism, and the inescapable strain of parent-child relationships caused by individual exploration of faith.

I'm happy to give content warnings for any of these! I really tried to push myself this month, and I feel like it paid off. I managed to get a few books off the really dusty and abandoned depths of my TBR list.

Fiction: 8

Nonfiction: 5

Total books this month: 13

Total fiction this year: 30

Total nonfiction this year: 36

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivian Maier Photographer Streets Ahead

Vivian Maier was a remarkable American street photographer whose 150,000 negatives that she took over a 50 year period were stored away and left unseen until after Maier’s death in 2009, at the age of 83. With the timely emergence of internet picture sites, Maier’s street photography was discovered, thanks to Chicago-based picture collectors such as John Maloof and Ron Slattery. Since then, Maier’s work has become the subject of worldwide interest with books, documentaries, and exhibitions being made about her life, in particular, the excellent 2014 documentary Finding Vivian Maier, which was also nominated for best documentary at the Oscars. Maier spent her youth between the United States and France before moving back to New York in 1951, primarily working as a nanny for most of her life. It is hard to know where to start with Maier’s work, it is so varied but ultimately would be an understatement to say Maier’s photographs do not feel like someone's old attic box brownie family photographs, although Maier did start her photography with a single shutter Brownie. Maier turns the everyday life that surrounded her in cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York into individual vignettes of films never made. Her best-known work represents the streets of New York and Chicago in the 1950s and 60s.

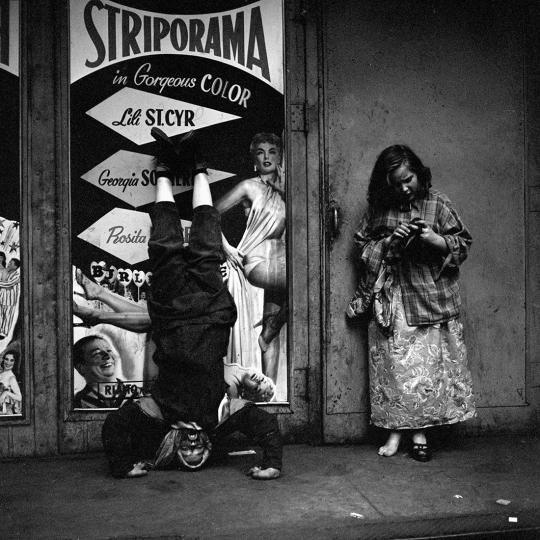

Maier often took self-portraits or photographs of her own shadow. In many of her self-portraits, Maier is reflected in the glass of a window or a blown-up shadow on a distant wall. I think Maier occasionally wants to be part of her own record but there is an unsureness that I can relate to; she is there but not there. Occasionally she is bold, and her reflection is captured in a window, sometimes revealed like a spectral presence, other times she is starkly represented in the reflection of a mirror that someone is carrying in the street. I love Maier’s self-portrait mirror shots; I feel I become her in that moment. I am transitorily there at the point where the shutter fleetingly opens to capture the light. One can see the scene Maier wants to capture and the capturer. Maier had such a great eye for trapping split-second dramas, be it a nun getting wheeled out on a stretcher, a man’s feet emerging and poking underneath a shop window blind, surrounded by food tins, or a film premiere with Kirk Douglas. Maier would walk around on her days off from nannying, traversing the windy streets from the upmarket to the poor areas of town. Nothing was off-subject, and it is a remarkable body of work.

Great care has also been taken in printing Maier’s negatives. A lot of images including the images from the official website were not originally printed by Maier and much debate about how a photographer wants to portray in physical form their negatives was studied in Maier’s case. According to the official website for Maier, Maier’s own printed photographs were examined, and notes were given to labs on how to crop and print etc, were used. One thing is sure, I am grateful that this valuable and significant archive of twentieth-century life was saved, but it does not just represent twentieth-century life. It is far from just a documentation of how we used to live. There is great artistry in Maier’s ability to find deeply humane moments in people's lives and somehow also turn each moment into the most important scene of the play or film.

Photographs of some of the poor areas and people are very powerful and Maier does not look away from their obvious suffering. It also shows Maier’s own humanity in documenting their struggles, I think that comes across in her work. She had a real kinship with those who were destitute. Maier was a socialist and feminist and, ironically, Maier would also find herself struggling in the last decades of her life and, at some point, did become homeless. Fortunately, some of Maier’s former children, whom she looked after, came together to help her find a small apartment to live in. Maier’s negatives were eventually sold off to pay off debts in 2007, two years before she died, and eventually were sold to collectors such as John Maloof who have taken great care in helping to get Maier’s work in the public domain. Maier was a very guarded and private person in her life. We do not know how she would view her newfound fame, but I for one am happy that I have had the opportunity to see some of Vivian Maier’s astounding work.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liste culturelle 2023

JANVIER

LIVRES

Le mur invisible de Marlen Haushofer

Histoire du Protestantisme de Jean Baudérot

FILMS

Godland de Hlynur Palmason

Dune de Denis Villeneuve

FEVRIER

SERIES

Tuca and Bertie de Lisa Hanawalt

Demon Slayer de Koyoharu Gotoge

FILMS

Le Retour des hirondelles de Li Ruijun

Wasabi de Gérald Krawczyk

All of Them Witches de Mona Panchal

LIVRES

Chaque geste compte. Manifeste contre l'impuissance publique de Dominique Bourg et Johann Chapoutot

La cabane magique. Panique à Pompéi de Mary Pope Osborne

Assassination classroom de Yusei Matsui

MARS

SERIES

Hollywood de Ryan Murphy

Supernatural de Eric Kripke

LIVRE

L’existentialisme est un humanisme de Jean-Paul Sartre

FILM

Fight Club de David Fincher

AVRIL

LIVRES

Peter Pan de Barrie

Informal beauty. The photograhs of Paul Nash de Simon Grant

Perceptions de Nathalie Man

La société des personnes vulnérables. Leçons féministes d’une crise. de Najat Vallaud-Belkacem et Sandra Laugier

Les hommes sont absents de Nathalie Man

FILMS

Bullet Train de David Leitch

Atonement de Joe Wright

Porco Rosso de Hayao Miyazaki

BlacKKKlansman de Spike Lee

Hokusai de Hajime Hashimoto

MAI

FILMS

It follows de David Robert Mitchell

Midsommar de Ari Aster

Little women de Greta Gerwig

Guardians of the Galaxy. Vol.3 de James Gunn

LIVRES

Le chat noir et autres histoires de Edgar Allan Poe

Déclaration des droits de la femme et du citoyen de Olympe de Gouges

JUIN

LIVRES

Émotions, souffrance, délivrance de Doctor Tuan Anh Tran

Capital: Vientiane de Guez, Pichelin and Troub's

Something to hide. Exploration des messages cachés du rock de Diego Gil et Johann Guyot

FILMS

Air de Ben Affleck

Eating our way to extinction de Kate Winslet

Susan, jour après jour de Stéphane Manchematin et Serge Steyer

Palm Springs de Marx Barbakow

Mike and Dave need wedding dates de Jake Szymanski

Clueless de Amy Heckerling

Spider-Man : Across the Spider-Verse de Joaquim dos Santos, Kemp Powers et Justin K.Thompson

JUILLET

LIVRES

Bathory. La comtesse maudite d'Anne-Perrine Couet

Une rainette en automne (et plus…) de Linnea Sterte

FILMS

Prisoners de Denis Villeneuve

Tarzan de Kevin Lima et Chris Buck

Turning Red de Domee Shi

AOUT

FILMS

Mercenaire de Sacha Wolff

Behind every good man de Nikolai Ursin

The Fast and the Furious de Rob Cohen

Born behind stones de Carina Freire

Lands that Rises and Descends de Moona Pennanen

LIVRE

Des âmes et des saisons : Psycho-écologie de Boris Cyrulnik

SEPTEMBRE

FILMS

Body Samples de Astrid de la Chapelle

Galb'Echaouf d'Abdessamad El Montassir

La ciudad de los fotógrafos de Sebastian Moreno

Happiest Season de Clea DuVall

En communauté de Camille Octobre Laperche

Barbie de Greta Gerwig

Encanto de Byron Howard et Jared Bush

Mon amour, mon ami d'Adriano Valerio

Bottoms d'Emma Seligman

LIVRES

Lettres à un jeune poète de Rainer Maria Rilke

Ich de Martina Weinhart

Poèmes à la nuit de Rainer Maria Rilke

SERIE

Downtown Abbey d'après l'oeuvre de Julian Fellowes

OCTOBRE

FILMS

Downtown Abbey de Michael Engler

Downtown Abbey : Une nouvelle ère de Simon Curtis

Sur le rocher de Sandrine Rouxel

Dangereuse Alliance d'Andrew Fleming

Folie douce, folie dure de Marine Laclotte

The Craft : Les Nouvelles sorcières de Zoe Lister-Jones

Trois mille ans à t'attendre de George Miller

The Crow d'Alex Proyas

Le jardin des planches de Monique Barrière

On vous parle du Chili : Ce que disait Allende de Chris Marker et Miguel Littin

LIVRES

L’œil et l'Esprit de Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Vivian Maier en toute discrétion de Françoise Perron

Des histoires vraies de Sophie Calle

Henri Cartier-Bresson des collections Photo Poche et introduction écrite par Jean Clair

Palm Springs 1960 - Robert Doisneau par Jean-Paul Dubois

Vivian Maier Self-Portraits de John Maloof et Elizabeth Avedon

NOVEMBRE

FILMS

Crimson Peak de Guillermo del Toro

Astérix et Obélix. Mission Cléopâtre d'Alain Chabat

Le Garçon et le Héron d'Hayao Miyazaki

Hamama & Caluna d'Andreas Muggli

Journal de Sébastien Laudenbach

In Paris Parks de Shirley Clarke

LIVRES

Ces hommes qui m'expliquent la vie de Rebecca Solnit

Pulp Poiesis : Écriture(s) en suspens(ion) d'Alizée Pichot

Enfant de la nuit polaire de Julia Nikitina

DECEMBRE

LIVRES

Nouveaux poèmes suivi de Requiem par Rainer Maria Rilke

Pampilles de Florentine Rey

Notes sur la mélodie des choses et autres textes de Rainer Maria Rilke

FILMS

Willy's Wonderland de Kevin Lewis

Family Switch de Joseph McGinty Nichol

Skyscraper de Shirley Clarke

Le monde après nous de Sam Esmail

Sensitive Content de Narges Kalhor

Snow Job : the Media Hyteria of Aids de Barbara Hammer

They Are Lost to Vision Altogether de Tom Kalin

Autour d'eux, la nuit de Vassili Schémann

Blight de John Smith

Tér d'Istvan Szabo

Chicken Run : La Menace nuggets de Sam Fell

SERIE

Lupin de George Kay et François Uzan

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self Portrait: Vivian Maier

#vivian maier#b&w photography#photography#self portrait#street photography#finding vivian maier#john maloof#vintage photoshoot#gordon parks#rolleiflex#diane arbus#robert frank#dorothea lange#chicago photographer#goat

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Week 2) Task:

Collect a range of self-portraits from at least 12 different photographers. (All resources need to be referenced correctly - i.e., you need to be able to identify the source.)

Vivian Maier:

Maier is a photographer whom I knew from my own research into portrait photography a year or two ago. She is famous for her self-portraiture were photos of her daily life over the years. The photos themselves weren't discovered until John Maloof found her negatives through an auction in 2007, not yet knowing the significance of her images. The significance of her images is that she was able to capture the beauty of street photography and the way she conveyed women and children through her images back in those days, along with her self portraits.

My favourite photo from her is one below:

Richard Avedon:

Richard is a well-known photographer for his fashion and portrait photography, especially when revolutionising fashion photography in collaboration with the famous designer brand, Vogue. Whilst he is famous for those, he is almost famous for his self-portraits, as the way he poses for the camera makes it feel very confrontational, yet inspires confidence. The use of black and white in most of his self-portraits help emphasise this, along with very strong lighting, which from a lot of his portrait work, seems to learn on bright lights aimed around him, or on top of him.

This is one I absolutely love from his collection of self-portraits. I can feel the energy coming out of this self-portrait in particular.

Jo Spence:

Jo Spece is a famous photographer. Best known for being a family portrait and a wedding photographer, she is also famous for her self-portrait work series, titled "Brave", as she re-defined portraits, along with showcasing the taboos that womenhood were experiencing at the time. She also enjoyed making these portraits, which is clearly shown through the images themselves.

Here is one that I particularly like from her series, it's just super weird, but at the same time, super intriguing:

Brooke Shaden:

Brooke Shaden is a photographer based in Los Angeles, USA. She is famous for her self-portraiture. It looks like fine art and really captures viewers. She takes a lot of inspiration from characters depicted from her childhood dreams to capture stunning images of wild imaginations and fears that she experienced in her childhood dreams.

This is my favourite photo from her series of self-portraits. It reminds me a lot of the famous scene in the movie "The Wizard of Oz" when Dorothy Gale opens the door to reveal the colourful world beyond the door from the black and white that we saw until then. The dull world that some of us experience here in reality and the thought of what could lie beyond the curtain in our wildest imaginations.

Robert Cornelius:

Robert Cornelius is famous as he invented the idea of doing portraiture of themselves through photography back in 1839, rather than through traditional art which was the norm at the time.

It is still fascinating how much detail is captured in this image, which is the very first photo of a self-portrait. Especially since photography was still very much in its infancy, and the amount of time needed to get good exposure.

Andy Warhol:

Andy Warhol's self-portraits are famous because they reflect his obsession with celebrity, identity, and image in the modern world. His works, particularly those created in the 1960s and 1980s, used bold colours, repetition, and his signature silkscreen technique to turn himself into a pop icon—just like the celebrities he depicted.

Ilse Bing:

Ilse Bing's "Self-Portrait in Mirrors" series is well-known for its use of mirrors, which challenged conventional portraiture by producing a fractured and multi-dimensional picture of the self. The picture examines the intricacy of identity and implies that it is impossible to convey in a single, still image. Bing's self-representation takes on a surreal dimension thanks to her work, which is influenced by avant-garde groups like Surrealism. She was one of the few female photographers at the time, and her technical proficiency and imaginative style made her a noteworthy character in photographic history.

I love this photo because of the way the expression is seen of her focusing on the shot. It's a view that people don't see often.

Cindy Sherman:

Cindy Sherman is famous for her self-portraits because she uses her own image to explore themes of identity, gender, and societal roles, often challenging traditional representations of women in art and media. Through her series of staged photographs, Sherman adopts various personas, costumes, and makeup to transform herself into different characters, questioning the idea of fixed identity. Her work often critiques stereotypes, particularly those found in fashion, film, and popular culture, making her one of the most influential artists in contemporary photography. Sherman’s self-portraits are known for their ability to provoke thought about the construction of identity and the performative aspects of self-presentation.

Robert Mapplethorpe:

Robert Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits are famous for their bold, direct, and often provocative exploration of identity, sexuality, and the human form. These self-portraits, especially those in the 1970s and 1980s, were part of his broader effort to challenge societal norms and expectations about beauty, masculinity, and eroticism. What sets Mapplethorpe's self-portraits apart is his use of meticulous composition and lighting, creating powerful and striking images that elevate the self-portrait genre into fine art.

His self-portraits often feature him in various roles, sometimes with explicit imagery or references to BDSM, confronting the viewer with questions about the relationship between the body, identity, and desire. Mapplethorpe's use of his own body as a subject allows him to explore themes of personal and sexual freedom, while also making his images deeply introspective and self-reflective.

These photographs were also controversial for their explicit nature, especially during a time when discussions of homosexuality, sexuality, and AIDS were fraught with stigma. Despite (or perhaps because of) the controversy, Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits remain iconic in contemporary art, illustrating the intersection of personal expression and societal taboo.

Diane Arbus:

What makes Arbus's self-portraits famous is how they reflect the same themes present in her renowned portraits of others: the idea of exposing the hidden or misunderstood aspects of human experience. Arbus’s self-portraits, like her portraits of outsiders, are candid, confrontational, and uncomfortable, challenging conventional representations of beauty and normality.

One of her most famous self-portraits shows her gazing directly at the camera with a candid, almost vulnerable expression, which reflects her interest in confronting societal taboos, especially regarding the marginalized or unconventional. This particular self-portrait is often seen as a reflection of Arbus’s deep curiosity about identity and her own struggle to understand her role in the world.

Her self-portraits are significant because they offer an intimate glimpse into her own psyche, blurring the lines between artist and subject. They also reflect the same sense of alienation and otherness that pervades much of her work, making her personal exploration of identity as challenging and thought-provoking as her depictions of the people she photographed.

D’Angelo Lovell Williams:

D’Angelo Lovell Williams' self-portraits are famous for their powerful exploration of identity, masculinity, race, and vulnerability. Through his work, Williams challenges conventional representations of Black masculinity by depicting himself in intimate, tender, and sometimes confrontational ways. His self-portraits often highlight themes of self-exploration, joy, tenderness, and resistance, creating space for a broader and more nuanced understanding of Black identity, especially within the context of contemporary photography.

What sets his self-portraits apart is the way he blends traditional portraiture with elements of storytelling, drawing on his personal experiences and the cultural significance of his identity. By capturing himself in both vulnerable and empowered poses, Williams shifts the narrative around Black men, showing them not just as strong or stoic figures but as multidimensional individuals who experience a wide range of emotions and personal journeys.

His use of light, color, and composition in his self-portraits also contributes to their emotional depth and visual impact, further enhancing the themes of introspection and personal empowerment. These elements make his self-portraits a powerful tool for redefining identity, challenging stereotypes, and creating space for more inclusive and diverse representations in the art world.

Pixy Liao

Pixy Liao’s self-portraits are well-known for their bold, subversive, and intimate exploration of gender, power dynamics, and relationships. Through her self-portraits, Liao challenges traditional norms around gender roles, often using her own body to explore themes of dominance, vulnerability, and the complexity of human connection. One of the most striking aspects of her work is her portrayal of herself in dominant and sometimes controlling positions, reversing traditional power structures, particularly in her relationship with her male partner, who is often depicted in more submissive or passive roles.

Liao’s self-portraits are not only visually compelling but also deeply conceptual, questioning societal expectations of gender and sexuality. She plays with the boundaries between performance and reality, blurring the lines between what is perceived as normal and what is subversive, and often incorporates humor and surreal elements to amplify her messages. Her use of photography as a tool to explore her own identity, both as a woman and as an artist, has made her a significant figure in contemporary art, particularly within the context of feminist discourse.

The emotional rawness, creative playfulness, and exploration of intimate themes in her self-portraits make Pixy Liao’s work both provocative and thought-provoking, earning her widespread recognition in the art world.

0 notes

Text

Finding Vivian Maier

John Maloof brought Vivians work to the light after buying the negatives at an auction. He wanted to know more about Vivian so he set out to get to know who this photographer was. She was a nanny to most and hid her photography away from the world, it was her secret, a time where she could be creative. She was a mysterious woman who didn't want to be known, she would tell people a different name then what her real name was, trying to conceal her identity or possibly another reason unheard of.

She would shoot self portraits as we know and portraits of other that where at a low angle, she didn't need to raise awareness that the camera was there and I think she wanted the image to be naturally staged in that way. Shes always finding her reflection and taking photographs of it, often with a natural expression. She was quite the hoarder and kept everything she had, she tried to find the art in every object and item that she saw.

I think that at the time Vivian concealed her work for a reason, I think that she wanted to keep her work for herself. It was said in the documentary that getting the recognition she deserved and seeing all the photographs was better that it happened after her passing because the spotlight would of been to much for her to handle. Maloof explains how he felt like he exposed her in a way but in the end her photographs where meant to be seen.

0 notes

Text

Vivian Maier: The Creative Personality Versus the Persona

— Written by: John Paul Jonas

In New York, the retrospective of Miss Vivian Maier (1926-2009), titled “Unseen Work,” recently concluded. The exhibition was open to visitors from May 31 to September 29, 2024, at the “Fotografiska New York” museum. The showcase included around 230 works covering the period from the early 1950s to the late 1990s, featuring many previously unseen photographs.

The exhibition highlighted Miss Maier's distinctive style and her extraordinary ability to capture the essence of everyday life through an artistic lens. It is part of a larger effort to bring her work to a wider audience, especially considering that her vast body of work was only discovered posthumously, yet it is already considered one of the most important contributions to 20th-century photography.

Organized in partnership with cultural institutions such as the John Maloof Collection in Chicago and the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York, this retrospective is part of an international tour that began in Paris in 2021.

Over the past 15 years, since the discovery of her archive, Miss Maier’s remarkable life story has captivated the international art community. Why?

Miss Maier was an American street photographer of French descent, born in 1926 in New York. She spent most of her life working as a nanny in Chicago. During her time off or on walks with the children she cared for, she dedicated herself to photographing the urban life around her, capturing candid and unfiltered moments of city life.

Although she remained unknown during her lifetime, her extensive archive—comprising over 150,000 negatives—was discovered in 2007 when Mr. John Maloof acquired the majority of her work at an auction. Fascinated by his discovery, Mr. Maloof became the driving force behind promoting her photographs, leading to the production of the Oscar-nominated documentary Finding Vivian Maier in 2013. Since then, interest in her extraordinary life and work has only grown. Following years of research, two comprehensive biographies have been published: Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife by Pamela Bannos in 2017 and Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny by Ann Marks in 2021.

In his renowned work On Liberty, John Stuart Mill reminds us: “Among the works of man, which human life is rightly devoted to perfecting and beautifying, the first in importance surely is man himself.” This observation aptly applies to the life and work of Miss Vivian Maier.

Anne Morin, curator of the exhibition Vivian Maier: A Photographic Revelation, shown across Europe, claims that Miss Maier is “one of the top street photographers, ever.” “Her story is definitely amazing, but I have to work hard to keep it separate from the physical reality of her photographs.” (Morin, as cited in Casper, 2014) [1] While I have no doubt about the sincerity of this intention, I fear such efforts may be in vain. Miss Maier’s most significant achievement is, indeed, her extraordinary life story. The art of photography forms the backbone of this narrative. It gave meaning to an otherwise unremarkable life—perhaps the highest gift art can bestow upon its creator.

“When we are involved in [creativity], we feel that we are living more fully than during the rest of life,” observes Professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, adding, “Even without success, creative persons find joy in a job well done.” [2] For an artist, separation from their art is a kind of torment, a confrontation with the meaninglessness of existence. When Miss Maier’s photographic walks ended in success, her daily duties as a nanny likely became less tedious and futile. The world’s imposed tasks could be viewed as necessary preparations for the next round of creation. A reasonable compromise.

Professor Csikszentmihalyi also suggests that no one can be both exceptional and normal at the same time. Miss Maier separated these two aspects of her life for the sake of survival—a creative compromise. For those around her, including the families she worked for, she presented herself as an unmarried yet proud modern woman, unusually interested in various aspects of contemporary life. “The personal accounts from people who knew Vivian are all very similar. She was eccentric, strong, heavily opinionated, highly intellectual, and intensely private. She wore a floppy hat, a long dress, wool coat, and men’s shoes and walked with a powerful stride.” [3]

Well-informed and empathetic toward the oppressed, she was diligent in imparting knowledge to her charges, often addressing challenging topics. Their walks included visits to impoverished parts of the city, with open discussions about current issues. Some audio recordings of these conversations, conducted in the form of interviews, were found among the artist's belongings. Similar efforts are confirmed by Mrs. Nancy Gensburg of Highland Park, whose three sons (John, Lane, and Matthew) were cared for by Miss Maier: “She wanted them to be very aware of what was going on in the world.” [4]

The artist’s identity intertwines significantly with her role as a caregiver, a profession that financially sustains both sides of her life. This unusual nanny finds ways to navigate the demands of daily life. At this stage, the dichotomy between her two personas isn’t yet fully expressed. It even seems that, in a harmonious blend, the creative personality might enrich the life and professional standing of the governess. As a photographer, she grants herself permission to dedicate valuable time, energy, and resources to a project that, at the very least, jeopardizes the practical survival of her career as a childcare provider. Always seeking knowledge and intellectual challenges, the artist approaches her vocation with both dedication and apparent detachment. “She captured politicians on the campaign trail (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, LBJ); celebrities at premieres or out in the wild (Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn); laborers and commuters; drunks, criminals, and down-and-outs; flâneurs [*] and well-coiffed women in furs”. [5]

The initial enthusiasm seems well-balanced and clearly directed. The financial support that Miss Maier manages to secure through her profession as a governess is apparently supplemented by a modest family inheritance. It appears that resources to fuel her creative spark are not lacking—quite the opposite. She frequently takes advantage of opportunities for extensive travel, during which she further broadens her intellectual horizons. These odysseys stand in stark contrast to the otherwise modest habits of the nanny. “Her thirst to be cultured led her around the globe. At this point we know of trips to Canada in 1951 and 1955, in 1957 to South America, in 1959 to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, in 1960 to Florida, in 1965 she’d travel to the Caribbean Islands, and so on. It is to be noted that she traveled alone and gravitated toward the less fortunate in society”. [3] The families she worked for generally viewed such excursions with leniency, tolerating the whims of their young, unmarried, and headstrong caregiver. “If she wanted to go, she’d just get up and go,” Nancy recalls. “The family would hire a temporary replacement while Maier was away; she never said where she was headed”. [4]

During her creative expeditions across the globe, Miss Maier photographed tirelessly. It is likely that during this period of intense travel and creative freedom, a strong artistic personality fully took shape. The desire for unrestricted movement and an independent choice of vocation remained powerful even upon her return to the role of governess. The families she worked for began to sense a shift in her approach to daily duties; unfortunately, the other Miss Maier—sensitive, original, and above all, productive—became inaccessible, even to those closest to her. “She really wasn’t interested in being a nanny at all,” Nancy Gensburg says. “But she didn’t know how to do anything else.” [4] The second part of this statement now seems both untrue and harsh. Many creative individuals who were not recognized in their own time face similar misconceptions. In Miss Maier’s case, we ask ourselves to what extent the artist herself is responsible for hiding her achievements from public view.

Based on the relatively sparse evidence currently available, we conclude that Miss Maier’s early creative work was far more visible and accessible, at least to those in her immediate surroundings. “There’s one family in New York that has hundreds of vintage Vivian photographs. In Chicago, she’d give people like two at the most. So she was much more generous and open with her photography in New York.” (Marks, as cited in Reid, 2021) [6]

It is evident that the pressures of daily life grew stronger with time. The creative personality would occasionally retreat, and the artist often made concessions. For example, in her creative process, she gradually abandoned post-production. The selection and processing of photographs, printing reproductions, and even developing negatives became increasingly unavailable luxuries. “In 1956, when Maier moved to Chicago, she enjoyed the luxury of a darkroom as well as a private bathroom. This allowed her to process her prints and develop her own rolls of B&W film.” [3] This convenience extended her control over the creative process—from capturing the image to developing the prints. The initiative of transforming her bathroom and sacrificing personal comfort demonstrates her deep commitment to accessing resources scarce for an artist in the social role of a nanny. Miss Maier consistently exhibited an undeniable dedication to learning, refining her artistic methods, and perfecting her technique. It wasn’t merely an exploration of her own vision of the world through the lens, but a sincere effort to realize, materialize, and ultimately present that vision to the people around her.

The seriousness of her intention to make some income from photography is evident in the fact that a number of her works were prepared for sale during post-production. “If you wanted a picture,” Nancy says, “you had to buy it. But Maier wasn’t selling her photography for profit. Someone had to want it more than she wanted it. It’s like an artist who would paint something and then hate to get rid of it. She loved everything she did.” [4] I doubt the comparison to a painter is quite fitting. We know that photographs can be reproduced an unlimited number of times. For similar reasons, visual artists create graphic works. Each print is authentic because it bears the artist's signature and a unique serial number from a limited edition. It’s likely that behind this apparent reluctance to sell her work lay different motivations. Perhaps Miss Maier wasn’t yet ready for this form of commerce—without an official representative, gallery, or agent who could properly assess the specific value. If that’s the case, maybe she was still waiting for the right opportunity to present herself to the world ‘the proper way.’ Perhaps the value she sought to achieve in the eyes of her contemporaries wasn’t financial. She was aware of her talent but lacked recognition.

Unfortunately, her working conditions during the later period were not as favorable. "As she would move from family to family, her rolls of undeveloped, unprinted work began to collect." [3] The creative process was diminished. From this period, the stereotype of the artist who creates out of an inner necessity, without any clear intention of sharing their work with the world, began to emerge. This complex dynamic between dedication to the art and neglect of the result creates the popular narrative about Miss Maier’s rich and self-sufficient inner world. Sophie Wright, the New York museum’s director, tells CNN: “There’s no audience in mind. There is no evidence that Maier wondered about her viewers—or that she ever imagined having viewers in the first place.” (Wright, as cited in Wexler, 2024) [7]

Professor Csikszentmihalyi reminds us that creative people are often intelligent but, at the same time, extremely naive. It is likely that the refined cultural habits she developed played a role in shaping and protecting her creative self. However, these habits also created a clear separation between her artistic identity and her social persona. This unintentional division left her vulnerable, deprived of understanding and support from the ‘ordinary’ world. “I once saw her taking a picture inside a refuse can,” talk show host Phil Donahue, who employed Maier as a nanny for less than a year, told Chicago magazine. “I never remotely thought that what she was doing would have some special artistic value.” (Donahue, as cited in Wexler, 2024) [7]

However, Miss Maier did not allow people or circumstances to take away her initial creative spark and authentic raison d’être. The boundary was clearly drawn on that front. “Her relationship with the world occurred through the camera, through the process of photographing/filming her surroundings,” comments Anne Morin, adding, “But once the recording was finished, she wasn’t as interested in looking at the result.” (Morin, as cited in Casper, 2014) [1]

The truth is, we will never know how painful the concessions to reality were. Was the act of photographing alone enough for Miss Maier? Could she truly choose? Or were choices made on her behalf by social and economic circumstances, as well as her marginalized position? While she carefully observed the world, no one saw her work after the photographs were taken—not even the artist herself.

It seems that the transition to color photography finally marked the quiet abandonment of any plan to enter the artistic scene, if such an intention ever existed. “Her color photographs focus on the musicality of the image, the forms, the density of the colors. She was really working in the medium of color when she took color photographs. In her black-and-white work, her focus seems to be on her subjects, the people pictured.” (Morin, as cited in Kasper, 2014) [1]

During this later period, faces gradually disappear from her photographs, giving way to abstract compositions in vibrant colors. Their artistic value is not diminished, but the sensibility has changed. If she had failed to connect with her contemporaries by skillfully capturing their portraits in scenes from everyday life familiar to everyone, that chance was certainly reduced by her prevailing choice of new subjects. In the bustling urban environment, there were plenty of themes, and Miss Maier gave due attention to each, despite the evident divergence from popular taste. “She cataloged the textures and cast-offs of the urban environment: graffiti, fire escapes, signs, garbage, shadows, abandoned newspapers, half-demolished buildings. She easily switched between registers.” [5]

We sense that an antagonism has always existed between Miss Maier’s creative self and her social mask, occasionally softened by fortunate circumstances. Finally, at some mysterious crossroads in her life, these two constructs tragically diverged. Instead of complementing and supporting each other, they grew apart. The artist gradually became a practical burden for the nanny. “When she interviewed with Zalman, a math professor at the University of Chicago, and Karen, a textbook editor, she made one thing clear: ‘I have to tell you, I come with my life, and my life is in boxes.’ No problem, they replied. They had a spacious garage. ‘We had no idea what we were in for,’ Zalman recalled. ‘She showed up with 200 boxes.’” [4]

Without the ability to bring her creative passion into the open, the “normal” nanny Maier was forced to endure. Proud and independent, she gradually retreated into a form of self-imposed exile toward the end of her life, relying on the goodwill of others. The rent for her final apartment was paid by the three brothers she once cared for, who remained deeply fond of her. Even they were unaware of her massive body of work. She rented storage lockers where she kept an enormous collection of negatives, photographic equipment, and numerous audio and video recordings. After a severe head injury from falling on ice around Christmas in 2008, she spent her last days in an emergency room. The three boys from Highland Park visited her daily. Their mother, Nenny Gensburg, noted: “She really was a unique person, but she didn’t think anything of herself.” [4]

When the rent on her storage lockers was not renewed, Miss Maier’s artistic legacy was auctioned off while she was still alive. No one in her circle knew anything about it. The secret was kept.

Why didn’t she confide in the people who embraced her? Would the world have collapsed? Yes. Her world would have. The carefully built facade would have crumbled irreversibly. She didn’t allow that, even when the remedy finally turned into poison. Her insecurity about her place in the world, perhaps rooted in her dysfunctional childhood, led to distrust and withdrawal from others. The world didn’t recognize the artist. It tolerated the well-read but eccentric persona. For the nanny, that was enough.

On the other hand, we wonder: during those fruitful decades, did the controlled “schizophrenia” between her private and public selves drive the engines of her vibrant and original creativity? Did the friction between these strange poles of existence generate the spark of creation? I believe this is beyond doubt.

The artist and the nanny courageously carried out their mission to the end. It is now up to the world to embrace and reconcile them, and finally display with pride the photographs from an unparalleled time capsule.

I'm an independent writer, and any contribution counts! If you enjoyed my work, you can buy me a coffee @ Ko-fi →

[1] Casper, J. (2014, July). Vivian Maier: Street photographer, revelation. LensCulture. Retrieved from:

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/vivian-maier-vivian-maier-street-photographer-revelation

[2] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperCollins.

[3] Maloof Collection, Ltd (n.d.). About Vivian Maier. Vivian Maier. Retrieved from:

https://www.vivianmaier.com/about-vivian-maier/

[4] O'Donnell, N. (2010, December 14). The life and work of street photographer Vivian Maier. Chicago Magazine. Retrieved from:

https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/January-2011/Vivian-Maier-Street-Photographer/

[5] Lybarge, J. (2021, Dec 21). The Trouble With Writing About Vivian Maier. The New Republic. Retrieved from:

https://newrepublic.com/article/164770/vivian-maier-photographer-biography-review

[6] Reid, K. (2021, Dec 7). Writing the True Story of Vivian Maier’s Life. Chicago Magazine. Retrieved from:

https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/december-2021/writing-the-true-story-of-vivian-maiers-life/

[7] Wexler, E. (2024, July 9). Meet Vivian Maier, the reclusive nanny who secretly became one of the best street photographers of the 20th century. Smithsonian Magazine. Preuzeto sa:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/meet-vivian-maier-reclusive-nanny-street-photographer-20th-century-180984665/

[*] Flâneur is a French term that refers to a person who strolls leisurely through urban spaces, observing and experiencing the surroundings without a specific destination or purpose. This concept embodies the idea of leisurely exploration, allowing the flâneur to engage with the environment in a reflective manner. Often associated with 19th-century Parisian culture, the flâneur is viewed as a detached observer of city life, embodying the spirit of modernity and the complexities of urban existence.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vivian Maier: Nanny With a Rolleiflex

Spread over two floors in the Fotografiska building in New York’s Flatiron District, the exhibition Vivian Maier: Unseen Work (which runs through September 29) reveals a trove of surprises. The late, great street photographer was also an evocative portraitist: Maier, a notorious loner, liked to click with people. The urban documentarian of humdrum life had a knack for humor and an eye for drama.

“The scenes she photographed are often anecdotes, coincidences, lapses of reality, the residual moments of life to which no one pays attention,” notes Anne Morin, director of DiChroma Photography in Madrid and the curator of the show. “Each of her images are situated in a place where the ordinary sheds its skin and becomes extraordinary.”

Unknown Legends

The Maier scenes range widely: from newspaper headlines peeking out from piles of debris to abstracted closeups of found objects; from candid surprised faces to random odd shots of homeless people sleeping on benches. Her Super 8 films explore waves of Chicago pedestrians, a detached swarm of humanity.

As the largest Maier retrospective yet shown in America, Unseen Work bears earmarks of completism. “Some of the newest images are quite aesthetic—but many leave you wondering the intentions,” opined the Phoblographer. “They leave me wondering why these images needed to be in a museum in the first place.”

By all indications, Maier’s photographs were not intended for museum walls. In her career as a nanny, she obsessively chronicled her life and times, but rarely shared her images with others—or even developed them into prints. Her pack-rat mentality preserved the negatives, hundreds of thousands of them stowed in boxes until the end of Maier’s life (at age 83) in 2009.

It was only afterward—when photo collectors including John Maloff and Jeff Goldstein brought her work into the art world, chronicled in Maloff’s fascinating 2013 documentary Finding Vivian Maier—that she became a photography star.

Lights Out

And Fotografiska New York is no ordinary museum. Founded in 2019 as a stateside installment in a global cadre of photography venues—in cities including Berlin, Stockholm, Tallinn, and Shanghai—the Manhattan locale has sported six floors of exhibition space and launched some 49 ambitious and far-ranging displays, from the eccentric to the mainstream. (Showing concurrently with Maier: Brooklyn street photographer Bruce Gilden and a bevy of People magazine’s iconic portraits.)

Fotografiska has been one of the few U.S. museums devoted to photography with the space and vision for shows usually found overseas in places like Madrid’s PhotoEspaña or Arles’s Les Rencontres de la Photographie. Sadly, having survived Covid, Fotografiska New York will close its doors on September 29, at the end of its exhibitions on Maier and Gilden. While tight-lipped about the future, the museum, a for-profit business, claims it will relocate somewhere in Manhattan with a broader floorspace.

“We’ve been having ongoing challenges with regard to the exhibition spaces,” executive director Sophie Wright told the New York Times about the move—which happens as the building changes owners. “The verticality of that building is not easy to manage. Our audience has been given a bumpy experience.”

Fotografiska hopes to announce a new temporary home soon. (Yet one can’t help thinking of restaurants closing “for renovation” and wondering whether they’ll ever reopen.) It’s somehow fitting that this venue’s swan song is a vast survey of a lonesome photographer who was unknown in her lifetime, rediscovered in the internet era, and somehow became emblematic of how we see one another in the world now.

The Art of the Selfie

According to the 2021 biography Vivian Maier Developed, by genealogist Ann Marks—which meticulously traces the artist’s life, with help from photo archives in the John Maloof Collection—Maier took up photography in earnest in her mid-20s after buying a top-viewing Rolleiflex camera. “It was designed to be held at the waist, facilitating inconspicuous picture taking,” Marks notes. “With its square format, there was no need to shift from horizontal to vertical positioning. … Soon she began to compose self-portraits while cradling her camera, presenting herself as a serious photographer.”

The reclusive Maier, who routinely hid her past and inner identity from people she met, had an affinity for selfies and left behind hundreds of them. “Vivian Maier is such a big phenomenon nowadays because this problem of [the] self-portrait resonates with the selfie culture we see today,” curator Morin told artsy.net. “All that crisis of identity we are viewing on social media, with tons of selfies, finds an echo in the work of Maier. Perhaps 30 years ago, she would not have been so famous or so interesting because the selfie was not so important at that time.”

Maier’s artful self-portraits, ranging from geometric mirror shots to peekaboo shadows, seem to reflect her evolving artistic personae: the confident young New Yorker who held professional photography aspirations; the adventurous, self-sufficient world traveler; the contented nanny in the Chicago suburbs who took her charges on photo trips around the city; and, later, the oft-uprooted worker who struck a lone pose against scenes of desolation and decay.

The Kids are Alright

Throughout her adult life, Maier worked as a nanny to support her creative calling as a photographer. Her stints of employment, and relationships with families who hired her, varied widely. (One gig with talk-show host Phil Donahue lasted just a few months.) By all accounts, she was most comfortable during the 11 years she spent with the Gensburg family in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, Illinois.

“She was like a real, live Mary Poppins,” Lane Gensburg later said of Maier. (However, Marks notes that Maier, a serious film buff, “wholeheartedly despised” the movie about the fictional nanny: “Her angry notes describe it as ‘outdated,’ ‘a real fiasco.’ and portraying a servant-child type of relationship.”)

In her years with the Gensburgs (1956–67), Maier bonded with the three brothers while documenting both their suburban lives and the cultural mosaic of the nearby Windy City. She left the family when the boys grew up but remained friendly. She never again found such a great fit.

Four decades later, at the end of her life, the Gensburg brothers helped Maier secure an apartment and then, after a head injury caused by a sidewalk fall, a live-in care facility. By then destitute, demented, and very delinquent on payments to a storage-locker company, Vivian Maier lost most of her possessions when the company auctioned them off.

Photo collectors John Maloof and Jeffrey Goldstein were among several bidders who claimed her photographs, negatives, and undeveloped film rolls (amid voluminous boxes of newspapers, books, broken cameras, and bric-a-brac, most of which was tossed or donated).

Maier never recovered from the fall. When she passed away in 2009, the Gensburgs held a memorial and published an obituary, which helped Maloof track down and identify the mysterious photographer whose images were, after appearing on Flickr and eBay, going viral and selling like pricey hotcakes in cyberspace.

Isolation and Empathy

Part of the paradox of Maier’s life and work is the disconnect between them. What the Gensburgs—or any of her employers—didn’t know about was her tangled family background, which she kept under wraps. She had her reasons: “She clearly concluded that no one would want to learn their nanny had an unstable, narcissistic mother; a violent, alcoholic father; and a drug-addicted, schizophrenic brother,” Marks explains. “It can safely be assumed that Vivian did not have DNA on her side.”

Long estranged from her nuclear family, Maier battled demons of her own: a severe and debilitating hoarding habit; and a condition that in Marks’ account, posthumously, experts term a “schizoid disorder.” The former wreaked plenty of havoc in Maier’s life, but also compelled her to preserve her trove of unpublished images. The latter strained her human interactions, yet may well have intensified her work.

Maier possessed a drive to document all her movements in the world, yet lacked any sense of follow-through in sharing them. She shunned close human contact (no hugs!) but found fascination in people she witnessed. She was detached enough to invade her subjects’ privacy, yet connected enough to see their lives. She expressed her inner self in outward reflections. She was of the last century, but it could’ve been ours.

Unlikely Legacy

After it was discovered by the art world, Maier’s body of work set off a feeding frenzy among collectors, curators, fellow photographers, critics, historians, photo aficionados … and capitalist venturers. With no direct heirs, the contents of her estate sparked disputes, lawsuits, and deal-making, with John Maloof emerging as the owner of the lion’s share of the archive and New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery as its U.S. rep. The work found its way to walls in dozens of museums around the world before landing at Fotografiska.

Who knows what Maier would say about all this? “Nothing is meant to last forever,” she once told an employer. “You have to make room for other people. It’s a wheel. You get on, you have to go to the end, and then someone else has the same opportunity.”

Through September 29, this body of work sits in a grand photo-exhibition venue that will soon be shuttered. Through the magic of the camera, reflections from the eyes of Vivian Maier have attained a sort of permanence.

~ Jack Crage · Jul 31, 2024.

1 note

·

View note