#Jo Fuku

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

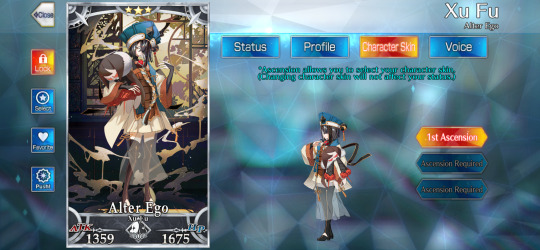

Summoned a new Alter Ego-class Servant:

☯️ Xu Fu! ☯️

#fgo#fate grand order#Fate/Grand Order Xu Fu#Fate/Grand Order Jo Fuku#FGO Xu Fu#FGO Jo Fuku#Xu Fu#Jo Fuku#Fuku Jo#徐福#Anime#fate go#fate/grand order#heroic spirit#fgo usa#taoist#sorcerer#Chinese sorcerer#fate/grand order: cosmos in the lostbelt#type-moon#type moon#lasengle#Alter Ego-Class#Alter Ego Class#Alter Ego#Fate/GO USA#Traum Singularity#Realm of the Thanatos Impulse Traum Life and Death of an Illusion#female heroic spirit#female servant

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

NAMES OF SIBLINGS: CLASS E

NOTE: doesn’t include Kurahashi and Mimura’s retconned (mentioned in one extra material, then not) brother(s).

Please credit me if you use my name ideas! I'd love to see what content you do with it :)

Hope you like it! I am open to feedback, questions if any, (about the themes™ or something else) and opinions. I'd love to talk more about my work.

Click on "ref." to see what the name is, well, referencing! it's a lot of Wikipedia nods and research from me.

ISOGAI (磯貝) Yuuma (悠馬)

Mother: Yukie (幸栄 "happiness, prosperous")

Younger brother, 6: Yutaka (裕 “affluence”)

Sister, 6 (twins): Yuko (裕子, latter meaning “abundance”)

OKAJIMA (岡島) Taiga (大河)

Older brother, 16: Takumi (匠海 “sea, craftsman” as Taiga means “river”)

OKANO (岡野) Hinata (ひなた)

Older brother, 17: Sora (そら “blue sky”, as Hinata means "sunny place")

Younger brother, 10: Haruki (はるき “spring, radiance” to keep up the theme)

KATAOKA (片岡) Megu (メグ)

Father: Ken (健 “strength” versatility in both Japanese and English)

Mother: Valérie (ヴァレリ “valuable, strong”) Durack (デュラック ref.)

Older brother, 24ish: Jo (譲 “transfer” as Megu is also a JPN/ENG name)

KANZAKI (神崎) Yukiko (有希子)

Older brother, 19ish: Nobushige “Nobu” (陳重, “Father of japanese civil law” ref.)

(or Nobuyoshi 信義 “faith, justice” ref.)

KIMURA (木村) Masayoshi (正義)

Younger brother, 11: Brave (勇気) (canon name)

SUGAYA (菅谷) “Sosuke” (創介)

Father, 65: Isamu (勇 ref.)

Mother, 60: Setsuko (節子 ref.)

Sister, 30: Fuku (譜矩 “music sheet”, “carpenters square” ref.)

Chosen name: Aya (彩 “coloring”)

SUGINO (杉野) Tomohito (友人)

Younger brother, 10: Ichirou (朗 ref. who is mentioned by Tomohito in this)

TAKEBAYASHI (竹林) Kotarou (孝太郎)

Oldest brother, 25: Kohei (孝��, “filial piety”, like Kotarou, “flat”)

Older brother, 22: Koichi (耕, “cultivate” same “Ko” syllable as his brothers)

CHIBA (千葉) Ryuunosuke (龍之介) name credits from @fumiko-matsubara post!

Older sister, 18: Rena (れな “beautiful”)

Younger sister, 12: Kohaku (琥珀 “amber, jewelled”)

Youngest sister, 7: Yuko (優子 “tender, child”)

TERASAKA (寺坂) Ryouma (竜馬)

Younger sister, 5ish: Ryoko (竜子 “dragon” (like her brother) “child”)

NAKAMURA (中村) Rio (莉桜)

Older brother, 20: Ren (蓮 “lotus” as Rio means "jasmine" and "cherry blossom")

HARA (原) Sumire (寿美鈴)

Father: Suzuo (鈴雄 “bell” (same kanji as Sumire), “male”)

Mother, from Shimane: Emiko (恵美子 “blessing, beauty (same kanji as Sumire), child”)

Younger brother, 9ish: Toshiki (寿樹 “longevity” (same kanji as Sumire), “trees”)

(or Susumu (進 “advance”))

Youngest brother, 6ish: Kazuma (寿馬 “longevity” (same kanji as Sumire) “horse”)

FUWA (不破) Yuzuki (優月) (from @xx0social-anxiety0xx)

Older brother: Minato (湊, ref.)

MAEHARA (前原) Hiroto (陽斗) (names from @maeiso-trash post, i just picked the kanji)

Oldest sister, 19: Mizuki (美月 “moon, beautiful” as Hiroto means sun)

Older sister, 17: Kiyoko (喜洋子 “rejoice, ocean child” as her siblings mean sun/moon)

MIMURA (三村) Kouki (航輝)

Mother: Wakana/ (和可女 “harmony, capable, woman”)

or Tomoe (知永 “eternity, wisdom”)

MIYAKE (三宅 “three house”, from Okayama prefecture)

MURAMATSU (村松) Takuya (拓哉) ref.

Younger brother, 12: Sho (翔 ref., keeping the “JOHNNY oshi” theme)

YADA (矢田) Touka (桃花)

Younger brother, 9: Kentaro (健太朗 “healthy/strength, plump, cheerful”)

YOSHIDA (吉田) Taisei (大成) ref.

Mother: Sokhna (ソクナ “woman, wife”) N’Diaye (ンジャイ)

Father: Shigeo (重夫 “ ref.)

Older Sister, 20: Tomoko (とも子 “friend, child” ref.)

RITSU (律)

Older sister/prototype: Første Artillerimodell (F.A.Mo)

#assassination classroom#ansatsu kyoushitsu#assassination classroom headcanons#yuuma isogai#hinata okano#megu kataoka#yukiko kanzaki#sugaya sousuke#sugino tomohito#chiba ryuunosuke#terasaka ryoma#rio nakamura#hiroto maehara#touka yada#taisei yoshida#hara sumire#takuya muramatsu#fuwa yuzuki#kotarou takebayashi#okajima taiga#masayoshi kimura#assassination classroom families#ritsu assassination classroom

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm actually somewhat disappointed that Dave the Diver doesn't have a bunch of different kinds of sushi.

A lot of it is just called "sushi." Though, it generally looks specifically like Nigiri.

Which, don't get me wrong. I love Nigiri, but it'd be nice to see Sashimi, Maki, Uramaki, Temaki, Chirashi, Usuzukuri, Gunkan, Futomaki, Tataki, Hako, Fuku-Kimo, Kan Jang Geh Jang (Raw Crab Marinated in Soy Sauce) too. Possibly others too, but I'm just not well-versed in sushi knowledge.

Unagizushi, Fukahire Sūpu (Shark Fin Soup), Fukahone Shuon Sūpu, Sae Woo Tui Kim (Korean Fried Shrimp), Oh Jing Oe Tui Kim (Korean Fried Squid), Jo Gae Gook (Korean Clam Soup), Mae Un Tang (Spicy Fish Stew), Hong Hap Tang (Mussel Soup), Book Eo Gook (Dried Pollack Soup), Kimbap, & even Hawaiian Hiu Punia & Musubi would've also been cool. I mean, it's also possible that they were in the game, they just weren't named like that, but still.

Also, Gumbo, Jambalaya, & Bouillabaisse!

I also noticed that there weren't any Dolphinfish or Blackthroated Perch or Flying Fish or Opah or Surmai, which is a bit disappointing, but whatever ya know. Like, we get to take a picture of a pair of Opah in the game, but it would've been cool to catch some too.

I mean, I hear that Dolphinfish isn't really the best sushi ingredient & that it's best fried, but it isn't like Bancho's got tunnel vision about it or anything, right?

He cooks other stuff.

Ooo... Imagine a crab boil... Or tempura... Mmm...

Like all different kinds of tempura. Ending with a full crustacean tempura feast.

Maybe seafood ramen & saimin?

At the same time, I hear that Blackthroated Perch, Flying Fish, Opah, & Surmai are actually very delicious as sushi. Opah specifically having 7 different textures of meat depending on the area of its body, which could be used to make a whole sushi set.

Though, I'm still trying to figure out why there are no Swordfish in the game...

And the fact that you can collect all these Clam Shells, but no clams is strange.

Ah, dude! Lancetfish or Oarfish paella & nikogori! But make it clear that you're not supposed to use the actual meat because the texture's no good. Too gelatinous.

You gotta heat the fish up so that the fats render & use that to flavor your food.

Maybe bagels & lox too. Fudge, I love bagels & lox.

I also wish that the sushi bar served sake & umeshu & shochu & stuff like that. Or! It'd be amazing if you could use Buckbeans to make your own beer & ale! Which you can do irl. Apparently, it takes fewer Buckbeans to do so than you would using hops! Which, cool! It's called gruit & grut ale, though you're not limited to just bogbeans. You can use any sort of bitter herb.

Also, you can make a type of wine outta Seagrapes.

Also, more recipes that use seagrapes! And maybe add sea asparagus & marine rice?

Either way, if there's ever a DLC or a sequel, I hope this sort of stuff gets added.

Random Stuff Masterlist

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (33): [For] Two Portions [of Koicha], Two Bowls are Displayed.

33) Ni fuku・ni wan kazari nari [二服・��碗飾也]¹.

[The writing (between the ten-ita and the ji-ita) reads: jo-jō (如常)².]

The kaki-ire [書入]³:

① [The utensils] may also be arranged in the manner shown⁴.

When [the host] is going to lower this tray [to the mat], first, the chawan in which the chasen has been prepared⁵ should be placed temporarily on the upper level, to the tray's left⁶. The chaire is then placed into the chawan that remains [on the tray], and [this chawan] is then moved to the very center of the tray⁷. Next, the chawan in which [the chasen] has been arranged is lowered [to the mat] in front of the furo⁸. After righting his posture, the [second] chawan, together with the chaire that is inside it, are picked up, and temporarily placed on the upper level⁹. Next the habōki is taken up and placed diagonally on the tray¹⁰. And then the chawan containing the chaire is picked up, and lowered into the place shown in the sketch¹¹.

[Finally] the nagabon is lowered [in front of the host's knees]¹², and immediately purified with the feather¹³. Then [the host] continues into the temae¹⁴.

The chawan in which the chasen had been arranged should be used later¹⁵.

② When the chawan are stacked together, it is best if a dry chakin is inserted between them [to protect the lower bowl from the foot of the upper one]¹⁶.

③ In general, when a chaire [that is displayed] without its covering, or a temmoku without its covering, is displayed on a tray, it is better if a fukusa-mono is placed underneath [to protect the tray]¹⁷. However, in the case of the shaku-naga[bon] and other [trays that are not lowered to the mat] like that, not placing anything underneath is also not a problem¹⁸.

[Alternately,] maybe a [piece of] white toweling, or perhaps a folded piece of tatō-shi [= kaishi], should be placed down¹⁹ -- but which of these depends on the utensil²⁰. In the case of things like the chaire, ordinarily [its] fukuro is put down [underneath]: this is the case with the taikai, sasa-mimi, and [other utensils] of that sort²¹.

_________________________

◎ This is another machi-shū temae from the early sixteenth century; and the contents of this entry make it extremely difficult to reconcile the sketch with the reality of the utensils that are supposed to be used -- indeed, it is impossible to perform the temae as narrated in the kaki-ire if one uses a tsune-no-nagabon [常ノ長盆], even though that is the tray that is named in the same kaki-ire. This entry (inadvertently) illustrates the pitfalls of trying to understand and interpret the Nampō Roku by only looking at the drawings, without an actual understanding of the real sizes of the objects that are being taken under consideration.

The sketch shows the kasane-chawan overlapping the second kane on the left by one-third, while the chaire also overlaps the central kane by one-third in the same direction. Furthermore, the habōki is, in the original sketch, shown to be associated with the end-most kane on the left; and, in the kaki-ire, the habōki is also described as being used to clean the tray. While it is possible to show all of these things in a sketch drawn freehand (such as the one found in the manuscript copies of Book Five of the the Nampō Roku), it is not possible to execute these arrangements using actual utensils -- as a consequence of the size of the utensils.

Because the kaki-ire states that the tray should be cleaned with the habōki, this (should) mean that the tray is an ordinary nagabon. But if the chawan and chaire are oriented as shown, and the tray is centered around them, the rim of an ordinary nagabon would extend fully to the first kane (as shown below), making it impossible for the habōki to contact that kane. Thus, the habōki would have to be centered between the tray and the left edge of the ten-ita, as I have shown.

This, indeed, is essentially how the arrangement is depicted in Shibayama Fugen's commentary (though he has the kasane-chawan resting atop their kane, but not as a mine-suri [峰摺り] -- which allows the objects displayed on the tray to fill it in a more visually pleasing way).

Unfortunately, if the habōki is not associated with a kane, the kane-wari count for the daisu will be chō [調], rather than han [半] (as it should be at the beginning of the goza). While the host could naturally compensate for this by the way he arranges the objects in the tokonoma, this would still be an anomaly among the arrangements that constitute Book Five of the Nampō Roku.

Another (and, in my opinion, the more likely) possibility is that, rather than an ordinary nagabon, perhaps it was intended that this temae be performed with a naka hō-bon [中方盆], the square tray that measures 1-shaku square (in the original sketchs, the tray is actually represented in the manner that is used elsewhere in Book Five to depict this smaller tray; and the relative size of the tray, when compared with the chawan and chaire, and the way it fits in between the kane, is also consistent with how things would be if a naka hō-bon were being used).

Additionally, the naka hō-bon is also the only way that the initial steps of the temae -- that are narrated in the first kaki-ire -- could be performed as described, because if one chawan is placed directly in front of the furo, and the other on the right side of the mat, but naturally not overlapping the heri, a tsune-no-nagabon could never be lowered between them safely, since the host’s hands naturally project beyond the rims of the tray on both sides. Consequently, it is this form of the temae that will be discussed below, in the “analysis of the arrangement” section.

Unfortunately, if this is the case, the traditional rule that trays smaller than the tsune-no-nagabon are supposed to be cleaned with the host’s fukusa, rather than the habōki, cannot be followed -- though, because we are dealing with a machi-shū temae (rather than one that was handed down from Nōami and Yoshimasa), we really cannot say how the machi-shū cleaned their trays during the early sixteenth century, with any degree of certainty. It is entirely possible (and, indeed, might even seem to coincide with the way they were doing things) that this group of chajin may have used a habōki to clean every tray, regardless of its size (the modern schools, for example, explicitly use the fukusa to clean only the chaire-bon, and even then they handle it in the same manner as the habōki was used; and this methodology appears to predate Sōtan, even though it is inconsistent with Rikyū’s teachings). We also cannot say to what extent the machi-shū chajin were following -- or even aware of -- the teachings of kane-wari. (Accounts of Jōō’s usages, however, suggest that while he was aware of the concept of kane-wari, he was not well informed about the details -- and, indeed, this would appear to be why he reached out to Kitamuki Dōchin, which ultimately brought about his acquaintance with the young Rikyū.)

There is, of course, a third possibility: that this arrangement (and, perhaps, the complete series of machi-shū temae) was interpolated from a source that had no connection with Jōō or his collection of daisu-temae, perhaps in the early decades of the Edo period when the (Imai Sōkyū-affiliated) machi-shū were asserting their hegemony over not only the contemporary practice of chanoyu, but the right to dictate its history as well. The inconsistencies in this temae, when compared with the details of the rest of the collection, easily leads us to this conclusion. This is the only arrangement in Book Five, for example, were apparently ordinary chawan are handled on a tray, and this alone should raise certain doubts -- if the temae is simply as it appears to be (as was mentioned above, in his commentary Tanaka Senshō expresses the belief that this temae was not used when serving noblemen, but, rather, on ordinary occasions -- because a dai-temmoku is not present). Yet these apparent departurs from the norm are not inherently inconsistent if we consider that the trays originally took the place of the shiki-shi [敷き紙] (even if, by the early sixteenth century, the shiki-shi had long been forgotten).

¹Ni fuku ・ ni wan kazari nari [二服・二碗飾也].

Two portions・two bowls are displayed.

Ni fuku [二服]: fuku [服] is the counting word for portions of koicha. Thus, two portions of koicha (that is, one portion is prepared in each of the chawan).

Nothing is said overtly, in this entry, with respect to the guests. But the beginning of the first kaki-ire implies* that, as in the previous instances, they might, once again, be noblemen. Perhaps this arrangement was intended for use by wabi-chajin -- persons unable to acquire things like the imported temmoku and other utensils -- when circumstances compelled them to serve tea to such noble individuals. On the other hand, Tanaka Senshō states that this temae was used when offering tea among equals (because a dai-temmoku is not used) -- albeit when observing the pre-modern convention of serving each guest an individual bowl of koicha (which would be consistent with the practices of Jōō’s day)†.

On the other hand, the reference to previous arrangement(s)‡ (particularly in the absence of any mention of concessions made to accommodate a specific kind of guest) could mean that this arrangement has been inserted here from some other source**. __________ *The first kaki-ire begins with the phrase kaku no gotoki mo kazaru [如此モカサル], “it may also be displayed as shown here.” The particle mo [モ] suggests that this is another in the same series -- and the previous several arrangements were specifically concerned with the service of tea to guests of noble standing.

†We must not forget that these temae date from a time when the daisu (or a tana built into a recess that resembled an o-chanoyu-dana -- such as Shukō seems to have installed in his two-mat residential cell) was always used for chanoyu.

As a result, even persons with extreme wabi inclinations (whether by preference, or necessity) would have done things in basically the same manner as those whose finances and inclinations allowed them to own a daisu.

‡While the phrasing of the first sentence suggests that this is yet another variation on the same theme (where two noblemen, of equal rank, were being served individual portions of koicha during the same temae), nothing is actually stated. Thus, this arrangement could have been interpolated from virtually anywhere.

**The language is somewhat anomalous, possibly suggesting that this entry was not originally part of Jōō's original collection. Of course, as has been mentioned before, we cannot be sure exactly when the kaki-ire were added to the sketches; or, indeed, whether they were all added at the same time, or on different occasions -- possibly separated from each other by years or decades.

The small collection of machi-shū arrangements that were inserted between the historical arrangements of the Higashiyama period and the series of cha・kō [茶・香] arrangements that Jōō seems to have borrowed from the Shino family’s usages, could have been added to Book Five of the Nampō Roku in order to validate the machi-shū’s practices by making it seem that these temae had been acknowledged (if not created) by Jōō. One thing that might support this assessment is that (in addition to the anachronistic quality of the language), in the case of these several temae, while it might be possible to perform them using Jōō’s chaire-bon, they would certainly be much easier to perform if the smaller trays preferred by Sōtan were used (coupled with the less-than-careful observence of the rules of kane-wari that characterized his -- and the machi-shū’s -- approach to chanoyu).

²Jo-jō [如常].

“The same as usual.”

The utensils placed on the ji-ita of the daisu are arranged as usual.

³The complete Japanese text of the kaki-ire read:

① Kaku no gotoki mo kazaru, kono bon shita [h]e kakae-orosu toki, saki chasen shikomi-taru chawan wo, bon yori hidari no kata jōdan ni kari ni oki, chaire wo ima hitotsu nokori-taru chawan [h]e iru, bon no mannaka [h]e yari, sate shikomi-taru chawan wo furo mae [h]e oroshi, tachi-agarite chaire tomo ni chawan torite, kari ni jōdan ni oki, habōki wo motte, bon no naka ni sujikai ni oku, chaire tomo ni chawan wo mochi-oroshi, zu no tokoro ni oki-tate nagabon kakae-orosu, sugu ni hane ni te kiyome, temae ni tori-tsugu beshi, chasen wo shikomi-taru chawan ha, ato ni tateru nari

[如此モカサル、此盆下ヘカヽヘヲロス時、先茶筌仕込タル茶碗ヲ、盆ヨリ左ノ方上段ニカリニヲキ、茶入ヲ今一ツ殘タル茶碗ヘ入、盆ノ眞中ヘヤリ、サテ仕込タル茶碗ヲ風爐前ヘヲロシ、立アカリテ茶入トモニ茶碗取テ、カリニ上段ニ置、羽帚ヲ以テ、盆ノ中ニスヂカイニ置、茶入トモニ茶碗ヲ持ヲロシ、圖ノ所ニヲキ立テ長盆カヽヘヲロス、スグニ羽ニテキヨメ、手前ニ取ツクヘシ、茶筌ヲ仕込タル茶碗ハ、後ニ立ル也].

② Kasane-chawan no toki ha, aida ni kawaki-chakin tatamite shiki-taru ga yoshi

[カサネ茶碗ノ時ハ、間ニカハキ茶巾タヽミテ敷タルカヨシ].

③ Sōjite hadaka chaire, hadaka temmoku bon uchi ni kazaru, fukusa-mono wo tatamite shiku ga yoshi, shaku-naga nado ha shikanu mo kurushikarazu, arui ha shiro-fukin wo shiki, arui ha tatō-shi wo shiku nari, dōgu sabetsu ari, chaire-rui ha oyoso ha fukuro wo shiku-beshi, taikai・sasa-mimi nado ni aru koto nari

[惣而ハダカ茶入、ハタカ天目盆内ニカサル、フクサモノヲタヽミテシクガヨシ、尺長ナトハシカヌモ不苦、アルイハ白布巾ヲシキ、アルイハタヽウ紙ヲシク也、道具差別アリ、茶入類ハ凡ハ袋ヲシクヘシ、大海・サヽ耳等ニアルコト也].

⁴Kaku no gotoki mo kazaru [如此モカサル].

As mentioned above, the present arrangement relies on previous ones for many of its details.

⁵Chasen shikomi-taru chawan [茶筌仕込タル茶碗].

Shikomu [仕込む] means “to prepare,” “to ready (something).”

In other words, this is the chawan in which the two chakin*, chasen, and chashaku have been placed.

Subsequently, in this kaki-ire, the reference to this bowl is abbreviated to shikomi-taru chawan [仕込タル茶碗], “the chawan that has been prepared.” __________ *One chakin is used to wipe the larger bowl (that is used to serve the first portion of koicha), and the second chakin is used to wipe this smaller bowl (which will be used second).

Using one chakin to clean both bowls would imply that this smaller bowl is inferior to the other, which would be insulting to the ji-kyaku.

⁶Saki chasen shikomi-taru chawan wo, bon yori hidari no kata jōdan ni kari ni oki [先茶筌仕込タル茶碗ヲ、盆ヨリ左ノ方上段ニカリニヲキ].

“At the beginning, the chawan in which the chasen has been prepared is temporarily placed on the jōdan, on the tray's left side.”

Bon yori hidari no kata [盆ヨリ左ノ方]: this potentially confusing statement seems to be following the usual practice of thinking about the objects on the daisu as if they were facing toward the host. Thus, “on the tray's left side” would mean on the right side of the ten-ita -- when things are viewed from our perspective. Indeed, this is the only place where there is room, since the left side of the ten-ita, between the tray and the edge of the shelf, is occupied by the habōki (whether it is associated with the first kane or not).

Jōdan ni [上段ニ]: on the upper level. Jōdan means the ten-ita, the upper shelf of the daisu. This is an anachronistic idiom, if we consider that these arrangements date from Jōō’s middle period.

⁷Chaire wo ima hitotsu nokori-taru chawan [h]e iru, bon no mannaka [h]e yari [茶入ヲ今一ツ殘タル茶碗ヘ入、盆ノ眞中ヘヤリ].

“The chaire is put into the single chawan that currently remains [on the tray], and [this assembly] is sent to the very center of the tray.”

Yaru [遣る] means to send to, dispatch. This is another word that is not typically used in this way in the rest of the Nampō Roku, and should be considered an anachronism.

⁸Sate shikomi-taru chawan wo furo mae [h]e oroshi [サテ仕込タル茶碗ヲ風爐前ヘヲロシ].

“Then the ‘prepared chawan’ is lowered [to the mat] in front of the furo.”

Since this chawan is functioning as a kae-chawan at this point in the temae, it is initially unclear why it is not simply placed on the left side of the mat, as is usual for this kind of bowl. Perhaps the reason is so as not to give the impression that this chawan is inferior to the other (though such considerations would be of greater importance if we consider that this temae is for the service of two noblemen of equal rank, rather than among equals -- when the shōkyaku would naturally take a sort of precedence over the ji-kyaku: this is the concession on which the ordinary kasane-chawan temae, where the second chawan is placed on the left side of the mat near the host’s knee, is based).

At any rate, it seems that this chawan remains in front of the furo during the first part of the temae, while the first portion of koicha is being prepared.

⁹Tachi-agarite chaire tomo ni chawan torite, kari ni jōdan ni oki [立アカリテ茶入トモニ茶碗取テ、カリニ上段ニ置].

“After righting [his] posture, the chaire that is standing on [the chawan], together with the chawan, are taken up, and temporarily placed on the upper level.”

Tachi-agarite [立ち上りて] would mean that after* the host rights his body (in order to be able to access the ten-ita), he can procede to execute (the following actions).

The chaire is standing within the chawan. This assembly is picked up and moved onto the ten-ita -- presumably to the same place recently vacated by the chawan in which the chasen had been prepared -- that is, to the right of the tray. (As mentioned above, it could not really be placed anywhere else, since the habōki is resting on the ten-ita on the other side of the tray.) ___________ *This phrase is in the past tense.

¹⁰Habōki wo motte, bon no naka ni sujikai ni oku [羽帚ヲ以テ、盆ノ中ニスヂカイニ置].

“When the habōki has been taken into the hand, it is placed on the tray, [oriented] on a diagonal.”

Motte [以テ] seems to be a mistake. The word should be motte [持って], meaning “has been grasped,” “has been taken into the hand.”

Sujikai [筋違い] means diagonally, obliquely.

Placing the habōki on an angle is both the natural way to place it on the tray*, and this orientation will allow the habōki to rest flat on the face of the tray (even if the tray is a naka hō-bon), without touching the sides. __________ *Held in the fingers of the right hand, the habōki is naturally oriented at an angle -- neither parallel to the chest, nor projecting straight forward (both of which require deliberate flexion or abduction of the wrist muscles).

¹¹Chaire tomo ni chawan wo mochi-oroshi, zu no tokoro ni oki-tate [茶入トモニ茶碗ヲ持ヲロシ、圖ノ所ニヲキ立テ長盆カヽヘヲロス].

“The chaire together with the chawan are brought down [from the ten-ita], and stood in the place indicated in the diagram.”

Chaire tomo ni chawan [茶入トモニ茶碗 = 茶入共に茶碗] designates the bowl that is now resting on the ten-ita, with the chaire inside.

Mochi-orosu [持ち下ろす] means to bring down [to the mat].

Zu no tokoro [圖の所], “the place in the diagram,” refers to the place in front of the daisu, where a chawan has been drawn in red, toward the right side of the mat. The chawan (with the chaire inside) should be far enough away so there is no danger of their being knocked over by the tray when it is lowered from the ten-ita.

¹²Nagabon kakae-orosu [長盆カヽヘヲロス].

“The nagabon is lowered by gathering it into the arms.”

Kakae-orosu [抱え下ろす], meaning “to gather something into the arms and then lower it (to the floor),” is an expression that is used nowhere else in the Nampō Roku*.

Usually this kind of idea is expressed, in the Nampō Roku, by ryō-te ni tori-oroshi [兩手に取り下ろし], or words to that effect.

This is also the only place where the word nagabon is found in the entire text of this entry†. Apart from this, everything (including the sketch) could just as easily refer to the naka hō-bon -- and, indeed, using that tray would allow everything to conform much better with what is shown in the sketch, in every detail. __________ *Anachronisms, and other unprecedented usages such as this, suggest that this entry is spurious, since the language of the Nampō Roku is generally very conservative. As I have mentioned before, this particular usage is confined to the kaki-ire associated with this small collection of machi-shū temae.

†As has been mentioned before, the kaki-ire were all added long after the sketches were made; and, in this case, either reflect the opinion of the Enkaku-ji scholars (which, in turn, would have been influenced by the arrangements that came before, and which follow, this one), or (more likely -- since the language is distinctly different from that associated with the Enkaku-ji scholars) the purposes of the person who was responsible for adding these several drawings to the collection. Because most of the other arrangements in this set use a nagabon (albeit in some the tsune-no-nagabon, while others employ the shaku-nagabon), the assumption seems to have been taken that this one uses a nagabon as well and so someone added this word to the kaki-ire.

In fact, none of the classical nagabon could be aligned with the kane as shown in the sketch (while a naka hō-bon could), so the issue would seem to boil down to an ignorance of the actual size of the objects used in the kazari, and “seeing what one wants to see” in the sketches.

¹³Sugu ni hane ni te kiyome [スグニ羽ニテキヨメ].

“Immediately it is purified with the feather.”

Sugu ni [直ぐに] means immediately, right away, at once, instantly.

Hane [羽], feather, is an abbreviation for habōki [羽帚 = 羽箒].

Kiyome [清め] means purification, cleansing.

¹⁴Temae ni tori-tsugu beshi [手前ニ取ツクヘシ].

“[And from this point, the host] should usher in [his] temae.”

Tori-tsugu [取り次ぐ] means to continue, pass on, transmit, convey, usher in, and so forth. Another unfamiliar usage, in so far as the Nampō Roku, taken as a whole, is concerned.

¹⁵Chasen wo shikomi-taru chawan ha, ato ni tateru nari [茶筌ヲ仕込タル茶碗ハ、後ニ立ル也].

“With respect to the chawan in which the chasen is prepared, subsequently [tea] is prepared [in it].”

In other words, this chawan (which is functioning as a kae-chawan during the first part of the temae*) is used to prepare the second portion of koicha, which will be offered to the ji-kyaku. ___________ *According to Rikyū’s writings, the smaller chawan is considered to be the kae-chawan. The point here is that a deliberate effort is being made to avoid characterizing this bowl as a kae-chawan on account of the inferior status that that name implies (as has been mentioned before, in the early days the omo-chawan [主茶碗] was used to serve the nobleman, while the kae-chawan was used to serve his attendants). This, in turn, argues that the present temae is indeed a part of the same series that began with entry 31 (Nampō Roku, Book 5 (31): the Display of Two Bowls when a Pair of Noble Guests [will be Served]), where two chawan are being used to serve two noblemen -- of equal rank -- in succession. It would hardly be necessary to say anything if the temae were simply a case of serving the shōkyaku, and then the ji-kyaku, during an ordinary gathering of equals, since, in such a setting, using the kae-chawan for the ji-kyaku during the kasane-chawan temae is done as a matter of course -- again, according to the interpretation voiced in Rikyū’s own writings.

¹⁶Kasane-chawan no toki ha, aida ni kawaki-chakin tatamite shiki-taru ga yoshi [カサネ茶碗ノ時ハ、間ニカハキ茶巾タヽミテ敷タルカヨシ].

“When stacked chawan are present, it is good if a folded dry chakin is spread between them.”

Kawaki-chakin [乾き茶巾] means a dry chakin -- that is, a new chakin that has never been dampened.

Tatamu [畳む] means to fold something. In this case, the dry chakin would probably be folded in half, since that would provide enough protection.

This piece of cloth protects the lower chawan from being scratched by the foot of the upper one. In the present day, a fukusa or ko-bukusa is often used in this way; but, since protection is the important point of the exercise, there is no reason why such a valuable piece of cloth* should be used, when an ordinary chakin, folded in half, will suffice. __________ *In the sixteenth century, cloth imported from the continent was still very rare -- and costly.

¹⁷Sōjite hadaka chaire, hadaka temmoku bon uchi ni kazaru, fukusa-mono wo tatamite shiku ga yoshi [惣而ハダカ茶入、ハタカ天目盆内ニカサル、フクサモノヲタヽミテシクガヨシ].

“On the whole, when a naked chaire, [or] naked temmoku, is displayed on a tray, it is better if a fukusa-mono is folded up and placed underneath.”

Sōjite [惣而 = 総じて] introduces a generalization.

Fukusa-mono [袱紗物] means a piece of (usually) imported cloth, cut from a bolt, folded in half, and with the open sides stitched with internal hems.

Given that the size was usually determined by the native width of the cloth from which it was made, when placed under a smaller object -- such as a chaire or a temmoku-chawan -- the fukusa-mono would probably be folded into quarters (as is usually done today).

The fukusa-mono protects the face of the tray from being scratched by the foot of the chaire or chawan.

¹⁸Shaku-naga nado ha shikanu mo kurushikarazu [尺長ナトハシカヌモ不苦].

“In the case of [trays] like the shaku-naga, there will be no problem if nothing is placed underneath [such utensils].”

The shaku-nagabon was placed on the ten-ita, and not lowered to the mat during the temae. Thus, the only time that the guests saw it (and even then, what they could see would be limited) was when it was displayed above eye level.

Since this kind of tray* was not used during the temae, slight scratches on the face would not be as much of a problem as if the tray were lowered to the mat (and then offered to the guests for haiken at the end of the temae, together with the other utensils, as described previously). __________ *This means any tray that is only placed on the ten-ita of the daisu, and never lowered to the mat during the temae. While the shaku-nagabon was the tray of this sort from Yoshimasa’s Higashiyama collection, other trays were made and used by the machi-shū for similar purposes (for example, in the present day, elongated trays of this sort are often used to hold the pair of chawan resting on dai, and the two containers of tea, that will be prepared during kencha [献茶] ceremonies -- when tea is offered to the Buddha, and so forth).

¹⁹Arui ha shiro-fukin wo shiki, arui ha tatō-shi wo shiku nari [アルイハ白布巾ヲシキ、アルイハタヽウ紙ヲシク也].

“Or possibly a white towel will be placed underneath; or maybe a folded piece of tatō-shi will be placed underneath.”

Tatō-shi [タヽウ 紙 = たとう 紙 = 畳紙]* literally means a folded piece of paper; but at the time when this kaki-ire was written, the term was used as an alternate name for the kaishi [懐紙]†. ___________ *This kanji compound can also be pronounced tatami-gami [たたみがみ], tatan-gami [たたんがみ], and tatō-gami [たとうがみ].

Tatō-shi -- or, according to Tanaka Senshō, simply tatō (as the reading for the entire compound タヽウ紙 = 畳紙) -- appears to be the form preferred in chanoyu (especially when referring to kaishi).

It will be recalled that a shiki-kami [敷紙] (to use the term found in Rikyū’s writings) is placed under a shin-nakatsugi [眞中次], when that tea container is displayed on a tana without a shifuku.

According to the Chanoyu san-byak’ka jō [茶湯三百箇條], the shiki-kami is made from several pieces of kaishi, folded together and then cut to the proper size (which is based on the diameter of the nakatsugi).

†This, nevertheless, is an anachronism, if we consider that the collection was assembled by Jōō, during his middle period.

²⁰Dōgu sabetsu ari [道具差別アリ].

“[One must] determine this based on the utensils.”

In other words, whether a fukusa-mono (meaning a piece of silk cloth, perhaps folded and shaped, with internal hems, and often made from imported cloth), a piece of white toweling*, or a piece of paper is placed under the utensil, depends on the utensil. ___________ *A shiro fukin [白布巾], a white towel, was made from the same cloth as a chakin -- but using a piece of cloth three times as long as it was wide, rather than half of the width as when making a chakin.

²¹Chaire-rui ha oyoso ha fukuro wo shiku-beshi, taikai・sasa-mimi nado ni aru koto nari [茶入類ハ凡ハ袋ヲシクヘシ、大海・サヽ耳等ニアルコト也].

“As a class, chaire should ordinarily have their fukuro spread out underneath: this is the case with the taikai, sasa-mimi, and others of that sort.”

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

As the only way to perform the temae that is described in the kaki-ire (or, indeed, distribute the utensils correctly on the ten-ita, according to what is shown in the original sketch) is with a naka hō-bon [中方盆], this is how the temae will be illustrated below.

The important details of the kazari itself are that:

◦ two chakin, a chasen, and the chashaku should be arranged in the smaller chawan, which is stacked inside the larger bowl (with a new, dry chakin, folded to fit, in between);

◦ the kasane-chawan and chaire should overlap their respective kane by one-third;

◦ the habōki should, likewise, overlap the left-most kane, with which it is associated.

The naka hō-bon being a kuguri-bon [潜り盆], the arrangement yields a kane-wari count of 5 (the naka hō-bon, habōki, furo, mizusashi, and koboshi all are in contact with a kane), which is han [半]. This is the correct count for the daisu when tea is served during the daytime*.

A fukusa-mono [袱紗物]† is placed under the kasane-chawan, to protect the tray from being scratched by the foot of the lower chawan.

The temae itself resembles the way the rai-bon [雷盆] is used when the temmoku and chaire are displayed on it‡ -- which was probably the source used by the machi-shū chajin when creating this temae.

1) When the host enters the room, at the beginning of the goza, he approaches the daisu and immediately lifts the smaller chawan out of the larger bowl, and rests it temporarily on the ten-ita, to the right of the tray.

2) Then he lifts the chaire into the larger bowl, picks up the chawan together with the fukusa-mono that has been placed underneath it, and moves that bowl to the center of the tray.

3) Then the smaller chawan is lowered from the ten-ita, and stood on the mat in front of the furo.

4) Then the large chawan (with the chaire inside it) is moved onto the ten-ita**, to the right of the tray.

5) Then the habōki is picked up and placed flat on the face of the tray. The habōki must be oriented on a diagonal, since it should not lean against the rims of the tray.

6) Then the large chawan, with the chaire still inside, is lowered to the mat, and stood near the right heri.

7) Then, using both hands, the naka hō-bon is lowered to the mat, and placed in between the two chawan (with the far rim touching the front edge of the daisu)††.

After cleaning the naka hō-bon, the habōki would presumably be placed on the go-sun-ita until the end of the temae.

==============================================

During the service of tea, both the chawan and the chaire are handled on the naka hō-bon. The disposition of the various utensils would be as shown below.

When preparing the first bowl of tea, the chakin that was used to dry the larger chawan should be placed on the ji-ita, in front of the furo, as usual: it should not seem that the smaller chawan is being used as a kae-chawan‡‡.

The second chakin remains in the smaller bowl until it is being used to prepare the second bowl of koicha. Then it, too, is placed on the ji-ita. ___________ *At night, when a chō [調] value is preferred, this is achieved by moving the habōki toward the left, so that it is no longer in contact with its kane.

†The word fukusa-mono [袱紗物] means a piece of silk cloth that is folded and sewn like a fukusa. However, unlike a temae-fukusa, this piece of cloth would be tailored to fit the purpose for which it was made. Usually imported cloth, such as donsu [緞子], was used for the fukusa-mono.

‡The rai-bon temae [雷盆手前] is described in the posts entitled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (19, 20): the Shin [眞] Arrangement of Two Utensils on the Rai-bon [雷盆]; and the Details of the Rai-bon Temae (Part 1), and Nampō Roku, Book 5 (21): the Details of the Rai-bon Temae (Part 2). The URL for these two posts are:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/623108862521851904/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-19-20-the-shin-%E7%9C%9E

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/623380671547801600/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-21-the-details-of-the

**After moving the chawan onto the ten-ita, the fukusa-mono is folded in half and inserted into the futokoro of the host’s kimono.

††The naka hō-bon should be 14-me from the right heri.

‡‡Because doing so would make it seem that the smaller chawan is inferior to the larger one. In the early days, the nobleman was served with the temmoku, and his attendants were subsequently served using the kae-chawan.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

avtomat

ko vem, da bom seksal,

si vzravnam hrbet,

pretvarjam se, da sem čaplja,

ki z lahkoto ulovi črvička

in s svojimi koraki izžareva prefinjenost

vsakič upam,

da je tudi meni erotika vtisnjena v kožo,

da volkovi komaj čakajo,

da me prelistajo

a moji sklepi se spremenijo v zobnike,

moji premiki v mehanično pornografijo,

da postanem le orodje

želja po ljubljenju je moja le do trenutka,

ko se njegove ustnice srečajo z mojimi,

ker takrat se mi organi strdijo v kovino,

ki si jo je prilastil, misleč da tudi zaslužil,

in sila postane gon po fuku

jaz mu to pustim

1 note

·

View note

Photo

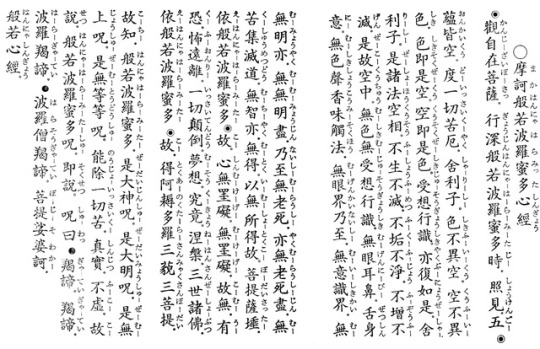

摩訶般若波羅蜜 Maka hannya-haramitashu (Japanese Heart Sutra)

まかはんにゃはらみたしんぎょう。かんじざいぼさつ。ぎょうじんはんにゃはらみたじ。しょうけんごうんかいくう。どいっさいくやく。しゃりし。しきふいくう。くうふいしき。しきそくぜくう。くうそくぜしき。じゅそうぎょうしきやくぶにょぜ。しゃりし。ぜしょほうくうそう。ふしょうふめつ。ふくふじょう。ふぞうふげん。ぜこくうちゅう。むしき. むじゅそうぎょうしき。むげんにびぜっしんい。むしきしょうこうみそくほう。むげんかい。ないしむいしきかい。むむみょう。やくむむみょうじん。ないしむろうし。やくむろうしじん。むくしゅうめつどう。むちやくむとく。いむしょとくこ。ぼだいさった。えはんにゃはらみたこ。しんむけいげ。 むけいげこ。むうくふ。 おんりいっさいてんどうむそう。くきょうねはん。さんぜしょうぶつ。えはんにゃはらみたこ。とくあのくたらさんみゃくさんぼだい。こちはんにゃはらみた。ぜだいじんしゅ。ぜだいみょうしゅ。ぜむじょうしゅ。ぜむとうどうしゅ。のうじょいっさいく。しんじつふここせつ。はんにゃはらみたしゅ。そくせつしゅわつ。 [ ぎゃていぎゃてい。はらぎゃてい。はらそうぎゃてい。ぼじそわか。] はんにゃしんぎょう。

maka-han nya haramita shin gyō. kan jizai bo-satsu. gyōjin hannya haramitaji. shō kengo un kaikū. doissaiku yaku. shari shi. shiki fuikū. kū fui shiki. shi kisoku ze kū. kūso Kuze shiki. ju sōgyō shiki yakubu nyo ze. sharishi. ze sho hō kū sō. fu shō fumetsu. fuku fujō. fuzō fugen. ze ko kūchū. mushiki. mu ju sōgyō shiki. mugenni bi zesshini. mu shiki shōkō miso ku hō. mugen kai. naishi mu ishiki kai. mumu myō. yaku mumu myō-jin. naishi mu rō shi. yaku mu rō shijin. muku shu umetsudou. muchi ya kumutoku. imu shotoku-ko. bodai satta. e hannya haramita ko. shin mu kei-ge. mu kei-ge ko. mū ku-fu. on Riissaite n dō musō. ku kyō ne han. sanze shō-butsu. e hannya haramita ko. toku ano ku tara-san myaku-san bo dai. kochi-han nya haramita. ze daijin shu. ze daimyō-shu. ze mujō-shu. ze mu to u dō shu. nō jo issaiku. Shinji tsu fuko kosetsu. hannya haramita shu. sokuse tsu shuwa tsu;

[ gya tei gya tei. hara gyatei. harasō gyatei. boji sowa ka. ] hannya shin gyō.

When Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva was practicing the profound Prajna Paramita she illuminated the Five Skandhas and saw that they are all empty and she crossed beyond all suffering and difficulty. Shariputra form does not differ from emptiness; emptiness does not differ from form. Form itself is emptiness, emptiness itself is form. So too are feeling, cognition, formation, and consciousness. Shariputra, all Dharmas are empty of characteristics. They are not produced, not destroyed, not defiled, not pure; and they neither increase nor diminish. Therefore, in emptiness there is no form, feeling, cognition, formation, or consciousness. No eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, or mind. No sights, sounds, smells, tastes, objects of touch, or Dharmas. No field of the eyes up to and including no field of mind consciousness and no ignorance or ending of ignorance. Up to and including no old age and death or ending of old age and death. There is no suffering, no accumulating, no extinction, and no way and no understanding and no attaining. Because nothing is attained, the Bodhisattva through reliance on Prajna Paramita is unimpeded in his mind. Because there is no impediment, he is not afraid, and he leaves distorted dream-thinking far behind. Ultimately Nirvana! All Buddhas of the three periods of time attain Anuttara-samyak-sambodhi through reliance on Prajna Paramita. Therefore know that Prajna Paramita is a Great Spiritual Mantra Therefore know that Prajna Paramita is a Great Spiritual Mantra. A Great Bright Mantra. A Supreme Mantra, an Unequalled Mantra. It can remove all suffering. It is genuine and not false. That is why the Mantra of Prajna Paramita was spoken. Recite it like this:

[Gaté Gaté Paragaté Parasamgaté Bodhi Svaha!]

Explanation

As a prajnaparamita (prajñāpāramitā 般若波羅蜜多) text, the Heart Sutra reveals the fundamental doctrine of Buddhism, that all phenomena are empty of any independent, substantial or eternal existence. In his first discourse to five ascetics in Deer Park at Sarnath, the Buddha revealed the most basic understanding necessary for the cessation of suffering, that a sentient being has no essential self, but is actually the momentary coalescence of the five skandhas (pañca-skandha 五蘊). form 色, sensation 受, perception 想, volition 行 and consciousness 識, and it is the misunderstanding of their coming together and falling apart that creates an illusion of self. As Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara realizes in the Sutra, all five skandhas are empty, In other words, not only is the Self devoid of any real, objective existence, so are the very skandhas that combine to create the illusion of a Self. It’s through this realization of emptiness, rather than impermanence, that the Bodhisattva overcomes all suffering.

This doctrine of emptiness is called sunyata (śūnyatā 空), and is the ultimate conclusion of the Buddha’s teaching that all things depend upon causes and conditions to arise and, therefore, lack any intrinsic nature. This revelation of impermanence set into motion the turning of the Wheel of the Law, as it is called in Buddhist tradition, and represents the beginning of the Buddha’s forty-five years of teaching.

Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara continues to apply this truth to all the basic components of the abhidharma thinking that Shariputra (Śāriputra 舍利子) represents in the text, including the eighteen bases of perceptual activity (dhātu 界) which include the six sense faculties (eye 眼, ear 耳, nose 鼻, tongue 舌, body 身, and mind 意), the six sensory objects (sight 色, sound 聲, scent 香, taste 味, touch 觸, and thought 法), and the the twelve links in the chain of causation, and the six perceptual awarenesses that arise from the contact between the sense faculty and its corresponding sensory object (e.g., visual 眼界 and mental awareness 意識界) and the Four Noble Truths.

Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara explains that even prajna, the very wisdom that arises through this penetratingly deep understanding of emptiness, is also empty, and that ultimately nothing is attained in the practice of prajnaparamita because there is nothing to attain and no one to attain it. This paradox of non-attainment is at the very heart of the prajnaparamita literature and is nowhere more clearly presented than in the Heart Sutra.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

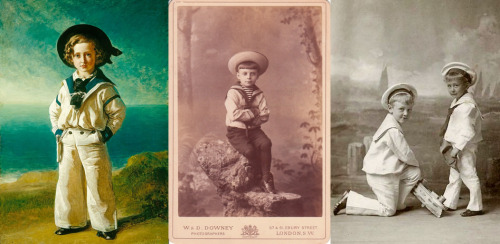

Style: Sailor Lolita

photo: pastelpeggy

Aujourd’hui nous allons parler de l’un des nombreux sous-styles de la mode lolita. Nous referons peut-être un point plus général sur le lolita, en attendant le sujet est traité dans tous les sens et tous les formats un peu partout. Si vous n’en connaissez pas bien les bases, nous vous invitons à faire une rapide recherche avant de continuer à lire cet article.

Le sailor lolita, qu’est-ce que c’est?

C’est tout simplement du lolita qui incorpore des éléments issus de l’esthétique de la navigation et des marins (sailor en anglais). Voilà c’est tout pour moi merci d’avoir lu et à bientôt.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

désolée j’étais obligée de faire cette blague.

Commençons par le commencement:

Pourquoi le sailor lolita?

Ce n’est qu’une hypothèse personnelle, mais il n’aura échappé à personne que l’uniforme marin et surtout son col iconique est très populaire au Japon, de par son adaptation en uniforme scolaire (sailor fuku, seifuku). Il est devenu un symbole de jeunesse et d’innocence appuyé par l’utilisation en masse dans la pop culture, notamment dans les manga et animes qui mettent souvent en scène des personnages encore scolarisés.

J’ai lutté pour ne pas mettre une image de Sailor Moon. Il est porté même en dehors de l’école, et peut être à la fois source de fierté (sentiment d’appartenance, car chaque école à un uniforme différent), costume de scène ou simple déguisement et -malheureusement- source de fantasmes plus ou moins avouables.

youtube

Video: Sailor Fuku wo Nugasanaide par Onyanko Club, 1985, qui compile tout le côté mignon et ambigu de l’uniforme scolaire, repris par AKB48 plus récemment.

Fun fact: le sailor fuku fut aussi porté dans d’autres modes, comme par exemple les Kogals (sous-style Gyaru, à gauche), avec des jupes raccourcies et chaussettes démesurées, customisation très moyennement appréciée par les écoles. A l’inverse, les sukeban (membres de gangs féminins, à droite) portaient les jupes très longues.

Mais je m’égare.

De nos jours ce style d’uniforme tend à disparaître pour quelque chose de plus moderne, un peu comme les uniformes anglais.

Mais au fait, comment en est-on arrivé à porter des costumes de marins dans les écoles japonaises?

La réponse est assez simple finalement: La modernisation et l’occidentalisation du Japon après la première Guerre Mondiale. Au début du XXe siècle en Europe, le costume marin était très populaire pour les enfants riches. Pourquoi? Parce que c’est mignon, eh. Non, et oui: en 1846, la reine Victoria fit confectionner pour son fils, le prince de Galles, âgé de 4 ans, une version miniature de l’uniforme réglementaire de la marine anglaise. L’uniforme fut porté, gravures et portraits furent créés (image de gauche). Plus efficace qu’un influenceur le jeune prince lança malgré lui la tendance: à la fin du XIXe siècle, on voyait des costumes marins partout, et ça se fait encore de nos jours.

Le vêtement étant populaire et relativement facile à coudre, il fut adopté par quelques écoles de filles japonaises en 1920 qui laissèrent tomber le kimono et le hakama que les élèves portaient jusqu’alors, sur l’initiative d’une principale ayant étudié au Royaume Uni (Elizabeth Lee, de l’université Fukuoka Jo Gakuin) La version masculine de l’uniforme scolaire est quant à elle basé sur la veste de l’armée de Prusse.

D’où vient le fameux col?

J’étais curieuse alors j’ai cherché.

Certains affirment qu’il était détachable et servait en premier lieu à protéger la chemise blanche de la saleté, notamment des cheveux longs que les marins enduisaient de substances diverses et variées. Il s’agit d’une légende.

Quand l’uniforme avec le col tel que nous le connaissons a commencé à se généraliser dans les années 1820-1850, les marins portaient déjà les cheveux courts par mesure d’hygiène (depuis environ 1800).

Avant ça, il n’y avait pas d’uniforme, les marins portaient des chemises simples. Le col a été agrandi graduellement au cours des années permettant d’évacuer la chaleur et la transpiration quand on l’ouvre en grand.

La partie arrière sert à protéger les épaules et le dos des éléments (vent, pluie, soleil...)

Le foulard de soie noué autour sert à la fois à tenir le col fermé, à la fois de chiffon, et peut aussi être utilisé autour du cou pour se protéger du froid et absorber la transpiration.

De nos jours les bateaux sont plus confortables et cet uniforme est toujours d’actualité surtout pour l’apparat et la tradition.

Revenons à nos lolitas

Il est de notoriété publique que l’époque victorienne est l’une des inspirations de la mode lolita, il est tout à fait possible que les multiples photos d’enfants victoriens en costume aient contribué à amener le thème marin dans le lolita mais j’en doute. En revanche le traditionnel uniforme d’école et la pop culture y sont surement pour beaucoup. Je ne peux pas l’affirmer avec certitude, je n’ai pas trouvé de sources quant aux débuts du sailor lolita...

Concrètement, ça ressemble à quoi?

C’est peut être par là que l’article aurait dû commencer, mais il n’y a pas tant de choses à dire...

La silhouette peut être aussi diversifiée que dans tous les sous-styles lolita: OP (robe) complète, JSK+blouse, blouse+jupe, à la taille classique, babydoll, empire...

Les couleurs sont pratiquement toujours le bleu marine et le blanc, parfois noir ou gris, avec des touches de rouge. Mais concrètement toutes les couleurs peuvent être utilisée, y compris les pastels et les palettes plus naturelles de beige et marron.

La tenue comporte pratiquement toujours le fameux col en V, celui-ci peut cependant prendre des formes différentes: parfois pointu, carré, arrondi, parfois remplacé par un col bateau. Il comporte souvent des lignes et parfois de la dentelle, rappelées sur la jupe.

Il peut être agrémenté d’un foulard, d’un nœud ou d’un ruban.

On y retrouve aussi d’autres éléments qui font référence au monde de la marine: _ bérets, casquettes voire chapeaux de paille, _ marinières et rayures _ motifs, broderies ou ornements avec ancres, boussoles, roues, cordes, blasons et drapeaux, bateaux/phares... _ Mais aussi des motifs relatifs à la mer: poissons et coquillages, sirènes etc.

photo: Lunie chan

Le style est très facilement adaptable en Ouji, il suffit de remplacer la jupe par un short! On voit souvent des bretelles de chaussettes et parfois un côté un peu plus militaire, rappelant un peu Ciel dans Black Butler ou Donald dans Kingdom Hearts

Le sailor lolita peut être facilement mélangé avec d’autres styles et thèmes pour donner une ambiance différente à la tenue. On va avoir deux axes: le côté scolaire/étudiant et le côté mer et navigation. Par exemple:

Uchuu Kei: certaines collection de Angelic Pretty par exemple, s’y prêtent très bien, comme Cosmic ou Dreamy Planetarium

Mahou Kei et éléments magical girl pour un look à la Sailor Moon ou école de sorcellerie

Sirène: evidemment!

Pin up: Les lolitas peuvent avoir une relation conflictuelle avec le pin up, mais le fait est qu’adapté correctement ça peut donner des choses très intéressantes! Les thèmes marins sont très populaires dans la mode rockabilly.

Pour conclure

Le sailor lolita est un style assez ancien mais facilement adaptable pour suivre les évolutions et les mélanges. Il a des règles qui semblent assez rigides mais finalement on peut en faire pas mal de choses et s’amuser.

De plus on peut trouver des vêtements qui conviennent à prix très abordable et il est facile de se lancer dans une coordination conventionnelle sans trop de risque.

Le sailor lolita convient aux néophytes comme aux plus expérimentés. Ca vaut vraiment le coup de se laisser tenter.

J’espère que cet article vous aura plu. Je n’avais pas beaucoup de chose à dire alors j’ai essayé de trouver des informations intéressantes autour du thème du jour. L’histoire de la mode est fascinante et on peut remonter loin et avoir des surprises quand on cherche pourquoi tel ou tel vêtement a pris cette forme ou est porté par telle catégories de personnes.

A bientôt pour un prochain article.

Sources:

http://www.victoriana.com/Victorian-Fashion/boysclothing-1890.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/School_uniforms_in_Japan https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sailor_suit https://www.quora.com/Why-do-sailor-s-shirts-have-the-big-flap-behind-the-collar http://www.landsailor.org/uniform-lore---myths.html https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/2pdr6j/how_did_the_sailor_suit_develop/ http://www.lolitaguidebook.com/lolita-substyles/sailor-lolita/

#street japan style#article#japanese style#japanese fashion#harajuku girl#harajuku boy#harajuku#fairy kei#aomoji kei#lolita fashion#sailor lolita#decorative#pastel goth#gyaru#mori kei#fashion#harajuku style#harajuku fashion#hadeko#uchuu kei#larme kei

1 note

·

View note

Text

{trans} TBS - WINGS TOUR ESPECIAL EN JAPÓN pt1.

¡El grupo de 7 miembros de hip hop que debutó en 2013, BTS!

Actuaciones de bailes increíbles.

Canciones que los miembros se escribieron.

Y canciones que son casi adictivas, su popularidad es la ebullición.

No sólo se limitó a Corea, sino que han clasificado al 1ro puesto en singles y álbumes semanales en Japón.

Para rematar, en América, ganaron el premio superior “Top Social Artist” en los BBMA 2017 de la música.

¡El mundo tiene sus ojos en ellos!

Aparte de su popularidad, el miembro de la banda que tiene el mayor poder en este momento

El líder de múltiples talentos, Rap Monster.

Rapero con carisma, Suga.

El mundo reconoció lo guapo que era, Jin

La esperanza de Bangtan, J-hope

La encantadora sonrisa, Jimin

4D actor e ídolo, V

El maknae de oro, Jungkook

¡La banda se formó en sus veinte años que han impactado el mundo, BTS!

Y el 10 de mayo en Roppongi Hills

En el evento de lanzamiento del álbum BTS ese día,

A los 2.500 aficionados que asistieron.

Realizaron sus dos nuevas canciones, "Blood, Sweat, and Tears" y "Spring Day"

Les preguntamos a los miembros sobre el encanto de su nueva canción.

NJ: Nuestro tema es sobre ser encontrado con la tentación, pero para la juventud, creo que hay preocupaciones y queremos ver eso como crecimiento e hicimos un montón de canciones sobre ello. Este es nuestro segundo álbum completo. Ahora, vamos a ver qué está pasando en su evento de lanzamiento.

OT7: Hola, somos BTS

Q: ¿Cómo va el evento?

NJ: Fue el mejor, no hemos actuado en Japón desde noviembre del año pasado. Así que estábamos todos un poco nerviosos. Pero muchos de ustedes vinieron hoy así que realmente pudimos disfrutar de la actuación, muchas gracias.

Q: ¿Cuál es el punto culminante de "Blood, Sweat, and Tears"

JH: Mi parte que tanta gente ha dicho que les ha gustado.”mani, mani” Las letras son las mismas que en coreano, por eso los fans son capaces de disfrutar de un tipo diferente de diversión.

Q: ¿Cuál es el punto de baile en "Blood, Sweat, and Tears"?

JK: Cuando cantamos, " Blood, Sweat, and Tears ", la ráfaga de cámara lenta tiene que ser controlada con el tiempo, por lo que es importante.

JH: ¡Control! ¿cómo? ¿cómo?

JN: Hemos preparado mucho para que podamos mostrar a todos un lado bueno de nosotros. ¿Cómo fue para todos ustedes?

Con el fin de ver a los fans japoneses de nuevo, preparado entre horarios ocupados es su nuevo álbum en japonés

¿Sus pensamientos sobre este evento?

YG: Fue nuestra primera vez en Roppongi. Esta vez hubo un montón de novedades para nosotros, me sorprendió mucho porque estaba lloviendo ese día. Pero un montón de fans se reunieron para divertirse junto a nosotros.

BTS llegó a Japón en medio de su gira mundial

Las cámaras de TBS vinieron a filmar el concierto de Osaka, el segundo día.

JH: Hola, mucho tiempo sin verte

Q: ¿Cómo es su condición?

TH: Estoy bien, ayer fue el primer día del concierto de Osaka. Y estoy realmente ansioso por el concierto de hoy, así que tengo muchas ganas de hacerlo.

JH: Ayer fue muy emocionante, así que estoy deseando hoy también.

Q: ¿Cómo te sientes hoy?

JH: El mejor

JK: Estoy deseando que llegue

JH: Hemos estado aquí mucho.

JK: Tienes razón

JH: Esta vez estamos haciendo 3 conciertos,3 días. Estoy realmente deseando que llegue.

TH: Hola, mucho tiempo sin verte ¿Cómo estás? Ser capaz de volver de nuevo con todo el mundo me hace muy feliz.

JIN: ¡Buenos días!

¿Al primer lugar que fueron cuando llegaron al lugar es...?

NJ: Hola, es una mañana refrescante, ¿no?

Q: ¿A dónde vas? Ensayos

NJ: Nuestra condición no está mal todavía, así que estamos que llegue mañana.

Incluso en el caótico horario de su gira mundial, los miembros estudiaron japonés para sus fans japoneses ¡impresionante!

JH: Vamos al ensayo

Siendo esta la tercera vez en este lugar, los miembros se relajan y se dirigen al ensayo

Q: Te gustaría poner cinta adhesiva

NJ: ¿Qué? ¿cinta? estoy bien. Para hacer los ensayos, necesitamos un equipo, no sé la palabra "equipo" en japonés.

Jimin está en medio de los preparativos

JK: Es como el mundo de la danza. Mundo de Danza.

STAFF: Vamos a comenzar con "Lie" para la gente que este en el escenario, por favor, baje.

El ensayo de hoy comienza con la etapa en solitario de Jimin.

¿Qué está haciendo el otro miembro durante el ensayo en solitario?

Mirando desde cerca, en medio de la filmación y concentrado en el baile.

Incluso durante los ensayos en solitario, los miembros disfrutan del performance y monitorean, es decir es BTS.

Jin mostrando las imágenes que tomó

JK: ¿Qué es esto?

JM: Eres malo en esto.

JN: Lo tomé desde al frente.

JM: Gracias

JN: ¿No es genial? En realidad me filmé, mira, en donde tus ojos están ocultos

Se aprecian mutuamente, una vista muy alentadora.

Empezando "I NEED U"

JM: Jungkook, estás muy adelante

JK: ¿De Verdad? eso es raro.

JM: Tanto para la introducción como para la parte principal, la banda es fuerte y causa confusión. ¿Puede bajar el volumen, por favor?

¿Cuál es la próxima canción de ensayo?

Rapmonster quién está bebiendo agua

JM: ¿Qué pasa?

Rapmonster de repente se ahogó con su bebida.

Y los miembros están preocupados en molestarlo.

JN. Pensé que eras un personaje de juego

JH: Fue un buen sonido

YG: ¿Por qué lo lanzaste?

NJ: No lo arrojé, me atraganté.

JK: ¿Qué opinas Jhope?

JN: ¿Estás bien?

JN: En realidad, sólo está Jhope para esto. (Para aligerar el estado de ánimo)

JH: ¿Hay algún problema?

STAFF: Estamos bien.

JH: Es una buena canción

TH: Demasiado interesante, fue realmente bueno.

Incluso con el cansancio de un viaje por todo el mundo, terminan el ensayo con una nota de diversión.

Mientras tanto, frente a la sala Osaka-jo que tiene 16.000 personas, están los fans que vinieron a apoyar.

Q: ¿Qué preparaste para la gira?

JM: Preparé mi dialecto de Osaka

JH: Por favor muéstranos un poco

JM: Solo un poco “Maido” “¡Maido!” Es todo por hoy.

JH: Eso es bueno

JK: Yo.. también, es algo que todos los miembros prepararon. Está preparado el lanzamiento de la canción en japonés, y queremos ser capaces de cantar muchas de las canciones en japonés. Y estudiar para poder memorizar el guión en japonés, hemos trabajado duro en muchas cosas.

YG: Este concierto es diferente a lo que usualmente hacemos, hemos estado estudiando japonés poco a poco, y también he memorizado palabras japonesas duras como, "reflejo condicionado" He memorizado palabras hasta ese momento ¿Sabes qué es un "extraño triángulo amoroso" en japonés? Así es como lo dices Y otros como "los humanos son ..."

JH: Memorizaste palabras que en su mayoría sonaban iguales que "preparadas".

NJ: Eso está mal.

YG: De hecho memoricé muchas palabras muy duras, palabras que tal vez no necesito saber.

JK: De seguro algún día las llegarás a usar.

YG: No sé por qué memoricé "reflejo condicionado"

NJ: Eres inteligente

TH: Preparé mi garganta para que pueda cantar correctamente

JN: Preparé el evento, rodos los días hice un evento de corazón y todos los fans los disfrutaron.

JH: ¿Por qué tan repentino?

JM: Muy lindo

JN: Se supone que debemos decir lo que preparamos

Q: ¿Preparaste corazones?

JN: Evento del corazón.

NJ: Las habilidades japonesas de todos avanzaron tan lentamente a través del estudio, por favor, envíen buenos pensamientos. Y cómo Suga mencionó, las letras y canciones son un poco diferentes. Nuestro nuevo álbum "Blood, Sweat, and Tears" es bueno y con sentimientos de gratitud. Hemos preparado un evento especial y canciones.

JH: Preparé mi energía ¡Todo el mundo ~ te mostraré ~!

NJ: Su energía es una locura

P: ¿Alguna anécdota durante los preparativos de la gira?

JN: Uno fue durante una preparación de rendimiento,

Rapmonster y yo somos lentos en aprender coreografía, así que tenemos que practicar fuera. Pero no hay espejo, así que éramos el espejo del otro y así es como lo practicamos.

NJ: Tal vez ese fue el problema.

JN: ¿Oh enserio? Eso parece

JH: Tal vez por eso no mejoras.

NJ: Quiero usar un buen espejo, Jungkook, por favor sea mi espejo.

JN: Jhope, vamos.

YG: El Tour en Japón tiene canciones japonesas así que tenemos que ser capaces de cambiar rápidamente. Hay canciones en las que las letras japonesas y coreanas se mezclan entre sí. Durante los ensayos, íbamos a coreano o japonés por lo que era difícil. Pero durante el concierto real pudimos hacerlo con éxito.

NJ: Taehyung, por favor. ¿Cómo estaban los fans de Osaka?

TH: Muy apasionados, Tokio. Nos escucharon seriamente

JH: Recordé un episodio en Nagoya, los fans hicieron un evento para mi cumpleaños .Fue el momento de "Episode II. The red bullet" Era mi cumpleaños así que prepararon un evento para mí, para los fans de Nagoya que hicieron eso por mí /hizo un corazón con las manos/

NJ: Dependiendo de la región, los colores de los fans son diferentes. Es la la pronunciación de la región.

Para Osaka, "Osaka ~" Un sentimiento de calor.

Tokio es un sentimiento más tranquilo.

Para Nagoya, "Nekkota", /la pronunciación de “mío” en coreano es similiar/ Son sentimientos de amor.

Q: ¿Qué pasa con Kobe?

JM/NJ/JH: ¡Ir! ¡Vaya! /pronunciación de “ir” es similar/

TH: ¿Sapporo?

TH/NJ: Sapporo ~ nieve

TH: Sa-poroporo (es el sonido para el goteo)

TH: ¡Fukuoka!

JM: Fuku! /Significa ropa/

TH: Fuku es fufuku

NJ: Significa ponerse caliente, ¿no?

2 notes

·

View notes