#Jacques Gaillard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

«KROKLOK», No. 4, Edited by Dom Sylvester Houédard, Writers Forum, London, ca. 1976 [room 3o2 books, Ottawa]

Contributors: Jeremy Adler, Aristophanes, Bill Bissett, Paula Claire, Thomas A Clark, Bob Cobbing, P. C. Fencott, John Furnival, Jean-Jacques Gaillard, Vasilisk Gnedov, Bill Griffiths, Sten Hanson, Raoul Hausmann, Dom Sylvester Houédard, Alexey Kruchenyk, Edward Lear, Anton Lotov, Kasimir Malevich, Steve McCaffery, Thomas More, bpNichol, Rabelais, Andrew Rawlinson, David Toop, Lawrence Upton, Charles Verey, J. P. Ward

#graphic design#art#poetry#concrete poetry#visual poetry#visual writing#magazine#cover#magazine cover#kroklok#dom sylvester houédard#dsh#writers forum#room 3o2 books#1970s

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

André Cros, Portrait du réalisateur Jacques Tati invité d'honneur de l'élection de la "Belle Gaillarde", accoudé à une table, fumant une cigarette, juillet 1961.

"La Belle Gaillarde" est une élection de miss qui a été créée à Noé (Haute-Garonne) durant l'été 1960 par Jacques Esterel, chansonnier et couturier, et Jean-Baptiste Doumeng, homme d'affaire et maire de Noé. L'élection de 1961 s'est déroulée du 8 au 10 juillet.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

André Cros, Portrait du réalisateur Jacques Tati invité d'honneur de l'élection de la "Belle Gaillarde", accoudé à une table, fumant une cigarette, juillet 1951.

"La Belle Gaillarde" es1951

t une éléction de miss qui a été créée à Noé (Haute-Garonne) durant l'été 1960 par Jacques Esterel, chansonnier et couturier, et Jean-Baptiste Doumeng, homme d'affaire et maire de Noé. L'élection de 1961 s'est déroulée du 8 au 10 juillet.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The next words he let out were 'pelargonium', 'goat's stable', 'Savoy cabbage' and 'Jacques Fearful' (the nickname of the assistant gardener at the nearby convent of the Women of Myrrhbearers, Madame Gaillard sometimes hired him for the hardest work, and he was notable for not washing himself once in his life)

(Das Parfum — Die Geschichte eines Mörders)

#artists on tumblr#the garden band#vada vada#vadavada#thegarden#art#digital art#cool art#рисование#drawing#fletcher shears#the garden#wyatt shears#the garden twins

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

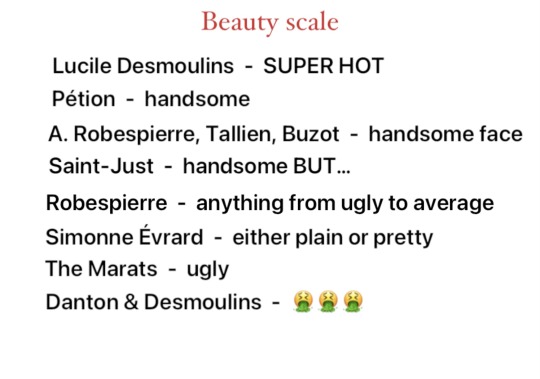

Georges Brassens (1953-1972)

Full titles: 1ère série : Georges Brassens chante les chansons poétiques (...et souvent gaillardes) de... Georges Brassens (1953), 2ème série [Le vent] (1954), No3 [Les sabots d'Hélène] (1955), No4 [Je me suis fait tout petit] (1956), No5 [Oncle Archibald] (1957), Volume 6 (1958), No7 [Les funérailles d'antan] (1960), 8 [Le temps ne fait rien à l'affaire] (1961), N° 9 [Les trompettes de la renommée] (1962), Les copains d'abord (1964), IX [Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète] (1966), 13 [Fernande] (1972)

Years ago, I went through all of Jacques Brel’s stuff – and to this day I regret not writing about it, at least in some form. Brel transformed so much of my musical taste, opening me up to pop traditionél and enlightening me as to how one man could dominate a stage, innately entrance hundreds, thousands, millions.

I won’t make that mistake again with Georges Brassens, another master of chanson who didn’t do so much lip-smacking or low-end belting but instead opted for wistful melodic innovation and high poetry. Brassens, too, was an extremely tall man and a captivating physical presence, and as much a poet as a conventional musician or performer.

In non-lyrical terms, it is Brassens’ melodic nimbleness, his restless and unwavering sailing through musical scales, that is most immediately endearing. One would like to think that even without understanding the lyrics, Brassens as man and personality is still perfectly graspable.

And yet it’s in lyrical terms that Brassens’ greatness truly lies. As poetry proper – poems put to music rather than music with poetic intent – his lyricism stands up to the finest written word (or at least of which I’ve cast an eye over). Appreciate this stuff best as an English-speaking listener by reading through translations, to realise how funny, cheeky, dark, lithe, poignant, conflicted, picturesque, interpretable it all is. I imagine much nuance and sophistication is still lost across linguistic boundaries – but even so, Brassens is masterful.

And there’s more. So much more, in fact, is there to be gleaned from Brassens and his context that I am not nearly knowledgeable enough that I cannot hope to engage with him with any satisfaction. Take his stratospheric popularity in France, for instance. This stuff, this beautiful, intricate, sophisticated poetry, had an extraordinarily huge audience. Is that not also fascinating? I’m no Francophile, but it becomes really quite understandable how the French, with the knowledge that this was their mass art, revel in an inflated sense of cultural superiority.

Pick(s): ‘Le gorille’, ‘Le vent’, ‘P… De To19i’, ‘Je me suis fait tout petit’, ‘Oncle Archibald’, ‘Le pornographe’, ‘Pénélope’, ‘Le temps ne fait rien à l'affaire’, ‘Les trompettes de la renommée’, ‘Les copains d'abord’, ‘Supplique pour être à la plage de sète’, ‘Fernande’

#Georges Brassens#1ère série : Georges Brassens chante les chansons poétiques (...et souvent gaillardes) de... Georges Brassens#2ème série [Le vent]#No3 [Les sabots d'Hélène]#No4 [Je me suis fait tout petit]#No5 [Oncle Archibald]#Volume 6#No7 [Les funérailles d'antan]#8 [Le temps ne fait rien à l'affaire]#N° 9 [Les trompettes de la renommée]#Les copains d'abord#IX [Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète]#Fernande#1953-1972#chanson#Chanson à texte

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

Wednesday Wanderings and Wonderings - The Passage Edition

Passage Vero-Dodat (19, rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau – 2, rue du Bouloi, 75001 Paris)

1826, two investors, the Charcutier Véro and l Dodat, decided to build a gallery between the streets of Bouloi and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. They built a neo-classical gallery with copper and cast iron ornaments, mirrors, paintings, columns, and a floor paved with black and white marble and globes of light. The Galerie Véro-Dodat owes its success to the store of the "Messageries Laffitte et Gaillard", located in front of the entrance, on Jean-Jacques Rousseau street. While waiting for their stagecoaches, travelers would stroll among the fashionable stores.

The Second Empire and the disappearance of the "Messageries" marked the decline of the gallery. Even if the gallery's appeal diminished, it continues to offer the visitor an image of the Belle Époque. It was remarkably restored in 1997. One can admire the splendidly restored coffered ceilings and the richness of the decorations. It contains art galleries, fashion boutiques, a famous violin maker and a "period" brasserie. (source)

*** But what is a passage? It is a private road open to the public, a shortcut between several roads, whether covered or not. As a pedestrian space, the passage can house both commerce and housing. Only the abundant decoration and the luxury of the stores differentiate a gallery from a passage. It’s the ancestor of today's shopping malls, the unique charm of Parisian covered passages will immediately transport you to the 19th century (Previous Posts)***

#CelineIsNotAnExpatAnymore#France life#Paris#passages#CelineWandersAndWondersInParis#CelineAndPassagesInParis

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Depuis 2003, la Galerie Grâce a exposé plus de 30 artistes

Nous tenons a leur rendre grâce ici et à leur associer les amis, poètes, écrivains, philosophes, prêtres, théologiens, psychanalystes, cinéastes, apiculteurs, musiciens... qui ont soutenu, permis ou participé à nos expositions et à nos actions. Nous n'oublions pas les artistes de tous les temps et de tous les art, qui ont inspirés et nourris nos travaux et notre cheminement. Nous avons dédié aux auteurs, écrivains, philosophes etc, notre Blog Attention l'art peut ressusciter la Vie ! ; et aux artistes un autre site, lui aussi intitulé Attention, l'art peut ressusciter la Vie !

La plupart de ces artistes et amis sont vivants et en activité. Dans la liste qui suit, leurs noms sont soulignés et associés à un site ; quelques-uns sont récemment nés au Ciel où ils prient pour le salut de notre humanité ; d'autres semblent avoir suivis d'autres voies...

Catherine Caba, artiste ; + Thierry Berlanda , philosophe, romancier, poète ; Marc Carniel, artiste ; Alain Cavalier, cinéaste ; Guy Delrez, artiste + ; Eddy Devolder, écrivain, artiste, Annick de Souzenelle, théologienne ; Réjean Dorval, artiste, galeriste ; Flore Dumortier, artiste ; Charlotte Dunker, artiste, graphiste : Robert Empain, artiste, poète, Carine Lauwers, créatrice, galeriste ; Michel Farin, père jésuite, écrivain, réalisateur de films : Marcelle Gaillard +, poète ; Aurélie Gatet,artiste ; Clara Gassull Quer , artiste, photographe ; Viviane Guelfi, historienne de l'art ; Bernard Hubot, artiste ; Jolie Julien, artiste ; Elise Mols, violoniste ; Jean-Marie Mahieu, artiste : Yvon Munster, artiste ; Philippe Pavageau, photographe, poète ; Laurence Skivée, artiste ; Jean-Marie Stroobans, artiste, galeriste ; Virginie Stricane, artiste ; Denis Vasse, prêtre, médecin, psychanalyste ; Jacques Vanderbiest +, prêtre ; Bart Vonck, poète ; Saskia Weyts, artiste ; Alain Winance, artiste

#Alain Cavalier#Thierry Berlanda#Guy Delrez#Robert Empain#Galerie Grâce#Bernard Hubot#Yvon Mouster#Jean-Marie Mahieu#Philippe Pavageau#Virginie Stricane#Denis Vasse#Bart Vonck#Alain Winance#Saskia Weyts

0 notes

Text

After a cat bit her hand, this writer suffered a frightening infection - The Washington Post

https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2025/01/18/cat-bite-infection-health-emergency/

Cat bites look very benign,” said Jacques H. Hacquebord, chief of the division of hand surgery at NYU Langone Health. “They just look like these little puncture wounds. But their teeth are so sharp; they’re like little needles, with the tip of it being bacteria.” And when you’re bitten by a cat, the pin-size wound tends to seal up quickly, trapping the bacteria and making the tissue beneath the skin a “fertile” ground for infection, Gaillard said.

In one study by the Mayo Clinic, 1 in 3 cat bites to the hand required hospitalization and some required surgery to clean the wound. In comparison, almost all dog bite ER patients are treated and sent home, even though the bacteria Pasteurella multocida is usually the culprit in both.

0 notes

Text

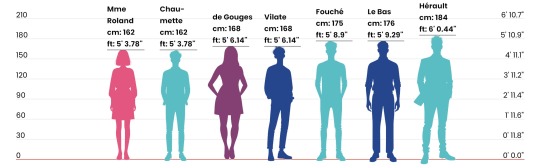

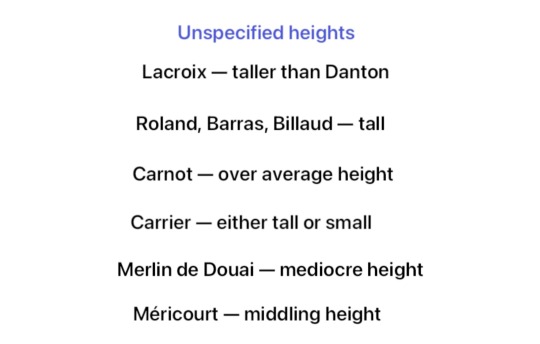

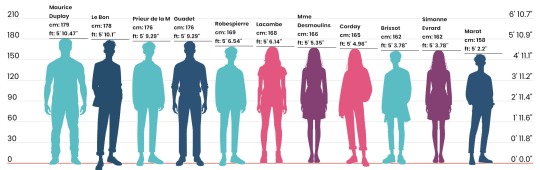

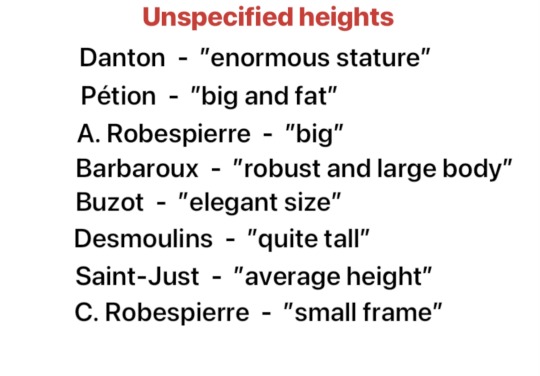

Philippe Le Bas — two passports from the year 1792 have been conserved, the first one stating ”height of five pieds five pouces (176 cm), brown (châtain) hair and eyebrows, gray-blue eyes, short and a bit snub nose, small mouth, round chin, big forehead, ovale face,” the other ”height of five pieds five pouces, brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, enlarged nose, middle sized mouth, long chin, ovale face, high forehead.” Cited in Le conventionnel Le Bas: d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1901) by Stéfane-Pol, page 26-27.

Élisabeth Le Bas — in Histoire de Robespierre et du coup d’état du 9 thermidor (1865) the historian Ernest Hamel describes Élisabeth in 1794 as ”one of the most charming blondes one could see.” Hamel is confirmed to have met Élisabeth’s son Philippe, but it is less clear if he also met Élisabeth herself. She had dark eyes according to Alphonse Esquiros, who on the other hand is confirmed to have met Élisabeth in her old age.

Lazare Carnot — According to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux: membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895) ”Carnot is of a height above mediocre. He’s not all that large, but his limbs are and indicate a strong frame; his face, quite well shaped, is slightly marked with smallpoxes. He has a big nose, small water-colored eyes; his hair is blond, thinning, and his forehead is bald; his complexion, a bland white one, does not offer any ruddy shade when he is calm. This pale color, combined with a dry and cunning look, gives him a false and cruel appearance, which repels at first and banishes confidence.”

Georges Couthon — Several contemporaries agree that Couthon looked cute. Pierre Paganel claimed in that he possessed ”a gentle look, a laughing mouth, a countenance which solicited tender affections and promised kindness. His eyes caressed you; his silence attracted you; each of his features expressed a kind feeling and invited you to love him. […] If you imagine this head which seemed to have been composed with a singular predilection, sadly leaning over a body half consumed by premature paralysis; if you consider that his look, marked with habitual pain, in some way accused Providence of having taken away his youth, by taking away the means to spend it happily, you have a fair idea of the keen interest that Couthon inspired in every sensitive man who saw him for the first time.” Barante, an enemy of Couthon, said that his face was ”gentle and pleasant,” his complexion ”dull,” features ”fine and firm,” his look ”gentle and passionate,” and his voice ”persuasive and emotional.” (cited in Georges Couthon (1983) by Albert Soboul). Maurice Gaillard, who met Couthon in May 1794, described his face as ”truly angelic” in a note written to Fouché somewhere during his time as Minister of Police, and in Souvernirs d’un sexagénarie (1833), Antoine Vincent Arnault called him ”the sweet Couthon,” even while describing his execution. In a letter dated September 29 1791 Couthon writes that he’s able to walk to the Legislative Assembly on foot. A year later, September 1792, he was however unable to use his legs and had to be carried, according to the testimony of Jacques-Antoine Dulaure (1794). When exactly Couthon got himself a wheelchair to get around appears to be unknown.

Hérault de Séchelles — A passport dated October 28 1793 documents the following: ”height of 5 pieds 8 pouces (184 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, medium sized nose, brown eyes, small mouth” (cited in Un épicurien sous la Terreur; Hérault de Séchelles (1759-1794); d'après des documents inédits (1907) by Emile Dard). In Mémoires sur les règnes de Louis XV et Louis XVI et sur la revolution (1886) Jean-Nicolas Dufort de Cheverny describes Hérault in early 1792 as ”big, well formed, with the most beautiful face possible,” and specifies in a footnote that Hérault ”was one of the most beautiful men in France.” Madame Roland too mentions that Hérault was good looking in her memoirs, noting that ”all these pretty boys seem to me to be poor patriots.” Hérault’s lover Suzanne Giroux de Morency wrote in Illyrine, ou l'écueil de l'inexpérience (1800) that Hérault was ”a beautiful man” and described his eyes as ”big” and ”superb.”

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette — a passport from 1784 states the following: ”height of five pieds, blond hair and eyebrows, blue eyes, a small hole under the left eye, somewhat large nose.” Cited in Mémoires de Chaumette sur la Révolution du 10 août 1792 (1893). According to Pierre Paganel, ”Chaumette was small, his waist thick and squat, his face broad and flat; he looked humble, his eyes were shy and delicate, and his countenance, if I may put it that way, was tearful. He possessed to the supreme degree the silent game of hypocrisy. Through modest and dreamy language one perceived a very resolute character. Long black [sic!] hair, coarse clothing, a more than slovenly outfit, hid a deep ambition from being seen.”

Paul Barras — According to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux: membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895) ”He was tall, strong, vigorous and very well built. He had quite handsome features, and was overall a very handsome man; but he looked harsh, his countenance was gloomy, his look sinister; serenity rarely appeared on his face. When he smiled, his smile, gracious in itself, resembled those rays of sunlight escaping through dark clouds which soon intercept them. He had a bad tone in society, and lacked distinction. He had neither that which comes from a noble soul and an elevated spirit, nor that which a careful education and association with good company gives. With a fine figure and a masculine face, he had no external dignity, and always retained something of that common and bold air that bad society gives.”

Sophie Momoro — Jean-Baptiste Laboureau, who met Sophie while they were both imprisoned in the Prison de Port-libre, wrote in his diary on March 19 1794 that she ”is very mundane; passable features, terrible teeth, the voice of a fishwife, an awkward appearance, that's what constitutes Madame Momoro.”

Théroigne de Mericourt — described as being of ”middling height” by former deputy Jacques-Antoine Dulaure in 1823 and psychiatrist Jean-Etienne-Dominique Esquirol in 1838, and ”somewhat above middle size of women” by English visitor John Moore in 1792. Dulaure writes she ”bore on her face the characteristics of vivacity and audacity,” Moore that she ”has a martial air, which in a man would not be disagreeable.” Théroigne was brown according to Dulaure, while Esquirol adds that she had brown (chátain) hair and big blue eyes. Moore describes her costume as ”a kind of English riding habit, but her jacket was the uniform of the national guards,” while Dulaure recalls ”with her blue cloth costume, her hat on her ear, her cane in her hand and sometimes pistols in her pockets, she appeared wherever trouble broke out.” Esquirol, who met Théroigne when she was hospitalized at the Pitié-Salpêtrière claims that she at the time was of ”mobile physiognomy, lively, clear, and even elegant gait.”

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti de Mirabeau — In Les Mirabeau: nouvelles etudes sur la societe francaise au XVIIIe siecle (1891) Louis de Loménie mentions a letter dated 1754, where Mirabeau’s uncle reported to his brother that ”your son is as ugly as Satan’s.” He’s five years old maybe chill a little? An equally unflattering descriptions is given by François René Chateaubriand, who in Mémoires d’Outre-tombe(1860) wrote that Danton was ”inferior in ugliness to Mirabeau,” and similar words can again be found in Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862): ”With Danton as with Mirabeau, speech was greatly aided by the gaze, the gesture and that energetic ugliness of the face.” In Considerations on the principal events of the French Revolution (1818) Germaine de Staël writes: ”The eye that was once fixed on [Mirabeau’s] countenance was not likely to be soon withdrawn: his immense head of hair distinguished him from amongst the rest, and suggested the idea that, like Samson, his strength depended on it; his countenance derived expression even from its ugliness; and his whole person conveyed the idea of irregular power, but still such power as we should expect to find in a tribune of the people.” A child who had seen Mirabeau during the procession that preceded the opening of the provincial Estates later recalled that he had ”thick hair, brushed up above his broad forehead, and ending in thick curls at the level of the ears” and again that ”there was something imposing about his ugliness.” (cited in Mirabeau(1973) by Antonia Vallentin). Finally, in a letter from 1770, Mirabeau’s uncle writes that ”I found him ugly, but he has not a bad physiognomy: and he has, behind the ravages of the smallpox, and features which are much changed, something graceful, intellectual and noble.” (cited in Mirabeau: A Life-history, in Four Books (1848) by John Stores Smith).

Merlin de Douai — according to Mémoires de Larevellière-Lépeaux : membre du Directoire executif de la République Française et de l'Institut national (1895): ”his size is mediocre; he is thin, dry and gaunt. The thinness of his face makes his large mouth, his big eyes and his long nose stand out rather unfavorably. He is devoid of grace and dignity in his deportment. When one hears him speak for the first time in a somewhat raised tone, one is singularly shocked by the strange character of his voice; it is false, sharp, uneven and has something wild about it.”

Olympe de Gouges — A police description cited on page 35 of Olympe de Gouges (1989) by Oliver Blanc gives the following information: ”height of 1,68 meters, oval face, brown hair and eyebrows, brown eyes, a slightly aquiline nose, an uncovered forehead, a round, full chin, a medium mouth.”

Joseph Fouché — According to Fouché: les silences de la pieuvre (2014) by Emmanuel de Waresquiel, measurements made of Fouché’s skeleton in 1873 show that he was 175 cm tall. He was meagre according to both Philippe-Paul de Ségur (in Mémoires du général comte de Ségur (1894-1895)), Charles Nodier (Souvenirs de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1850)), Mathieu Molé and Victorine de Chastenay (Mémoires de madame de Chastenay, 1771-1815: L'empire. La restauration. Les cent-jours(1897)), who also all agree that there was something piercing about Fouché’s eyes. Said eyes were small according to Chastenay (who also adds that they were very close together) and Ségur. Nodier writes that they were of a light blue colour, while Chastenay calls them ”very red,” and Ségur and Molé ”bloody.” Chastenay, Ségur and Nodier do also each call Fouché pale, the latter even writing that it was ”a particular pallor, which belonged only to him” noting that it was clearly different from someone with anemia or other illness. This, combined with the testimony of Fouché’s ”red eyes,” hint at the idea that he was albino. In his memoirs (1896), Barras does indeed outright call Fouché’s child ”an actual albino,” while Molé writes Fouché had ”the dry hair of an albino.” Speaking of his hair, Ségur writes that it was ”flat and rare” and that Fouché was towheaded (cheveux couleur de filasse). Chastenay too underlines that ”in his youth his hair had been or should have been a very bland blond.” According to Barras, both Fouché and his wife Bonne-Jeanne Coiquaud did however have red hair. According to the memoirs(1834) of Charlotte Robespierre, ”Fouché wasn’t handsome,” and according to those of Barras, Fouché and his wife were a ”hideous couple.” Molé instead writes that he had ”fine features,” and that ”something at once ferocious, elegant and agile makes him resemble a panther.” Ségur on the other hand likened Fouché’s physiognomy to that of ”an agitated weasel” and writes that he had a ”long and mobile” face. Fouché ”spoke with ease” according to Chastenay, had ”a dry voice” according to Molé, and had a ”brief and jerky speech, consistent with his restless and convulsive attitude” according to Ségur.

Manon Roland — In her memoirs, Manon gives the following detailed description of herself: ”At fourteen, like today, I was about five pieds (162 cm) tall; my size had acquired all its growth; the leg well shaped, the foot well placed, the hips very raised, the chest broad, the shoulders effaced, the attitude firm and graceful, the walk rapid and light; this is what first hit the eye. There was nothing striking about my face, only great freshness, a lot of softness and expression. By detailing each of the features, one can ask oneself: Where is the beauty? Nothing is regular, everything pleases. The mouth is a little big; there are a thousand prettier ones; not one has a more tender and seductive smile. The eyes, on the contrary, are not very large, their iris is a grey-chestnut; but placed not very deep in the sockets, with an open, frank, lively and gentle gaze, crowned with brown eyebrows the same colour as the hair, and well defined, they vary in their expression, like the affectionate soul whose movements they paint; serious and proud, they sometimes surprise; but they caress much more, and always wakes you up. My nose was causing me some pain, I found it a little big at the tip; however, I considered that overall, and especially in profile, it did not spoil anything else. The broad, bare forehead, little covered at that age, supported by the very high orbit of the eye, and in the middle of which veins in Greek vanished at the slightest emotion, was far from the the insignificance that one finds on so many faces. As for the fairly upturned chin, it has precisely the characteristics that the physiognomies indicate for those of voluptuousness; when I bring them together with everything that is particular to me, I doubt that anyone was ever more made for it, and enjoyed it less. Bright rather than very white complexion, dazzling colors, frequently enhanced by the sudden redness of boiling blood, excited by the most sensitive nerves; the soft skin, the rounded arm, the pleasant hand, without being small, because its elongated and slender fingers announce skill and retain grace; fresh, tidy teeth; the plumpness of perfect health: such are the treasures that nature had given me. I have lost many, especially those who are plump and fresh; those who remain with me still hide, without me using any art, five to six of my years; and the very people who see me every day need me to tell them my age, to believe that I am over thirty-two or thirty-three. […] My portrait has been drawn several times, painted and engraved: none of these imitations gives the idea of my person; it is difficult to grasp because I have more soul than face, more expression than features. […] Camille Desmoulins was right to be surprised that at my age, and with so little beauty, I had what he calls admirers.” Interestingly though, despite describing herself as only 162 cm tall, Manon gets called tall by both her friend Helen Maria Williams in Memoirs Of The Reign Of Robespierre (1795), as well as by Honoré Riouffe (who claimed to have seen her at the Conciergerie prison) in Mémoires d’un détenu pour servir à l’histoire de la tyrannie de Robespierre(1795).

Jean Marie Roland — in 1792, John Moore described Roland as ”about fifty years of age, tall, thin, of a mild countenance and pale complexion. His drefs, every time I have seen him, has been the same, a drab-coloured suit lined with green silk, his grey hair hanging loose” and that his ”manner is unassuming and modest” in his diary. According to Mémoires du marquis de Ferrières: avec une notice sur sa vie, des notes et des éclaircissemens historiques (1821) ”Roland looked like Plutarch or a Quaker in his Sunday best. Flat hair, little powder, a black coat, shoes with cords instead of buckles, made him look like a rhinoceros. However, he had a decent and pleasant face.”

Charles Alexis Brûlart de Genlis, the marquis de Sillery — in Memoirs Of The Reign Of Robespierre(1795) Helen Maria Williams writes Sillery had white hair by the time of his execution in October 1793.

Jean Baptiste Carrier — According to Pierre Paganel, ”Carrier was taller than the ordinary. He had an unpleasant face, but it was not very sinister.” At the time of his trial, a witness did instead describe him as "small, thick, stocky, he had black, frizzy hair and a swarthy complexion, his enormous, hanging lower lip gave him the vague appearance of a Negro" (cited in Carrier et la Terreur nantaise (1987) by Jean-Joël Brégeon).

Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varennes — Jacques Bernard, who met Billaud in 1800, wrote that ”he was tall, his broad, pale face did not reveal, by any external sign, a very energetic soul. His countenance was full of gentleness, he wore a wig of red hair, in the Jacobin style. His accent, his manners announced affability and a distinction that his costume, more than simple, could not erase. Trousers, a coarse canvas jacket, a wide-brimmed hat, large shoes, such was the costume of this Spartan.” Cited in Billaud-Varenne, membre du Comité de salut public : mémoires inédits et correspondance / accompagnés de notices biographiques sur Billaud-Varenne et Collot-d'Herbois par Alfred Bégis(1893)

Jean-François Lacroix — According to the memoirs (1913) of Théodore de Lameth, Lacroix was ”of a frightening size and eloquence.” J.G Millingen agrees, writing in his Recollections of Republican France 1791-1801 (1848) that Lacroix was a man of ”colossal stature.” Millingen also attributes the following words to Lacroix, said at the foot of the scaffold: ”Do you see that axe, Danton? Well, even when my head is struck off I shall be taller than you!”

Joachim Vilate — height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm), brown (châtains) hair and eyebrows. Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les derniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ”the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ”thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728)

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#round 2!#frev#fouché#théroigne de méricourt#philippe le bas#élisabeth le bas#carnot#mirabeau#billaud varenne#carrier#manon roland#jean marie roland#olympe de gouges#couthon#paul barras#included vilate only in case anyone ever wants to make a super detailed dramatization of camille throwing himself in his arms#following the girondins getting sentenced to death#or robespierre smashing a plate in front of him

301 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jacques Monestier, Le Défenseur du Temps, 1979, reactivated by Cyprien Gaillard, 2022. Soundtrack composition, Hit by Cyprien Gaillard, Joe Williams, and Heal by Laraaji. Brass, lead, steel, speakers, microswitches and transducers. Pictured below, Palais de la Découverte 2022, created using vitrified sbestos

(via Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and Paris in transition | Wallpaper)

0 notes

Text

The wife of an American doctor suddenly vanishes in Paris and, to find her, he navigates a puzzling web of language, locale, laissez-faire cops, triplicate-form filling bureaucrats and a defiant, mysterious waif who knows more than she tells. Credits: TheMovieDb. Film Cast: Dr. Richard Walker: Harrison Ford Michelle: Emmanuelle Seigner Sondra Walker: Betty Buckley Wino: Dominique Pinon Le Grand Hotel Manager: Jacques Ciron Williams: John Mahoney Shaap: Jimmie Ray Weeks Peter: David Huddleston Edie: Alexandra Stewart Kidnapper: Yorgo Voyagis Taxi Driver: Djiby Soumare Bellboy 2: Roch Leibovici Desk Clerk: Dominique Virton Gaillard: Gérard Klein Bellboy: Stéphane D’Audeville Hall Porter: Laurent Spielvogel Hall Porter: Alain Doutey Tourist: Louise Vincent Hotel Detective Le Grand Hotel: Patrice Melennec Restroom Attendant: Ella Jaroszewicz Florist: Joëlle Lagneau Florist: Jean-Pierre Delage Cafe Owner: Marc Dudicourt Waiter: Artus de Penguern Desk Cop: Richard Dieux Inspector: Yves Rénier U.S. Security Officer: Robert Ground Marine Guard: Bruce Lester-Johnson U.S. Embassy Clerk: Michael Morris U.S. Embassy Clerk: Claude Doineau Blue Parrot Barman: André Quiqui Rastafarian: Thomas M. Pollard Dede Martin: Böll Boyer TWA Clerk: Tina Sportolaro Extra (uncredited): Angela Featherstone Taxi Driver Who Hands Over the Matches to Dr. Walker (uncred: Roman Polanski Bellboy 3: Alan Ladd Film Crew: Casting: Bonnie Timmermann Original Music Composer: Ennio Morricone Assistant Art Director: Gérard Viard Writer: Gérard Brach Writer: Roman Polanski Producer: Thom Mount Director of Photography: Witold Sobociński Costume Design: Anthony Powell Casting: Margot Capelier Editor: Sam O’Steen Additional Writing: Robert Towne Stunt Double: Vic Armstrong Production Design: Pierre Guffroy Production Sound Mixer: Jean-Pierre Ruh Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Jean-François Auger Sound Editor: Jean Goudier Hairstylist: Jean-Max Guérin Makeup Artist: Didier Lavergne Supervising Sound Editor: Laurent Quaglio Producer: Tim Hampton Additional Writing: Jeff Gross Sound Effects: Jean-Pierre Lelong Sound Re-Recording Mixer: Dean Humphreys Assistant Art Director: Albert Rajau Choreographer: Derf La Chapelle Stunt Double: Wendy Leech Movie Reviews: JPV852: Movie starts off well enough with the mystery element but afterward tonally felt a bit off (veered into moderate comedy at points). Ford is fine as was Emmanuelle Seigner, though I wonder if this could’ve used the eye of Brian De Palma rather than Polanski. **3.25/5** kevin2019: “Frantic” is an engrossing and well made film that easily builds up a genuine sense of mystery and intrigue from the very beginning. It is incredibly well crafted throughout with an immediately interesting opening gambit and Roman Polanski is a seasoned director and he knows precisely how to create a natural and rhythmic momentum to the proceedings and to then successfully maintain it at a certain level without any evidence of indecision on his part in terms of how the film ought to proceed in order to achieve its maximum potential and effectiveness. This results in a splendid film that effortlessly retains a compelling quality until the very end and it provides the perfect showcase for the romantic city of Paris even though it also makes you pause for thought about visiting there on Valentine’s Day.

#doctor#espionage#france#hotel room#husband wife relationship#intrigue#man looking for wife#man woman relationship#married couple#missing wife#neo-noir#Paris#Top Rated Movies#wife

0 notes

Text

Hubert Selby Jr, deux ou trois choses

Extrait du film : Hubert Selby Jr, deux ou trois choses – 1999 Réalisation : Ludovic Cantais Image : Florence Levasseur Son : Jacques Sans Montage : Yvan Gaillard

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

PARTITIONS, NOTES (Hiver-Printemps 2024)

Dimanche 4 février 2024, Opéra de Lyon, grande salle : Barbe Bleue de Jacques Offenbach (reprise), mise en scène Laurent Pelly, vif plaisir de légèreté et d'intelligence. Mise en scène d'un spécialiste de la finesse parodique, Laurent Pelly vers qui je cours dès qu'il entreprend Offenbach, depuis sa Belle Hélène du Châtelet (Paris) (Décembre 2001), impeccable réussite.

La scène se passe à la ferme, un peu, puis à...

...l'Élysée à la foule de conseillers aux costumes ajustés, humiliés par cet histrion de Roi Bobèche, dangereux, despotique, parfaitement comique et agité. À la cour de Bobèche, ils n'obéissent qu'à un seul devoir : courber l'échine, à quoi s'emploie bientôt tout le plateau, hilarant jeu de scène et pantomime. Le public, bien sûr, pige et rigole de bon coeur à ce qui devient la rengaine de la pièce : '...qu'un bon courtisan s'incline, 'zan s'incline, 'zan s'incline', tout comme comme il y avait dans La Belle Hélène, ce 'roi barbu qui s'avance, bu qui s'avance, bu qui s'avance, bu qui s'avance', sortes de galop entraînants et de rythmes niais, déglingages joyeux, charges sans concession.

Tout tourne avec bonheur autour du tempérament sensuel et amoureux de Boulotte, du monde au balcon, gouaille emballante, à qui rien ne résiste. Les amoureux sont gentils et innocents, ils vont finir par joliment gagner la partie (rebondissements, et mariage), mais Boulotte a un autre projet dramatique, exposé d'entrée : 'Mais saperlotte mais saperlotte, y'en a pas un' pour égaler la p'tit' Boulotte Dès qu'il s'agit de batifoler.' Et Barbe Bleue n'est pas le dernier à apprécier, qui s'enthousiasme : 'c'est un Rubens, c'est un Rubens, ce qu'on appelle une gaillarde'. Un connaisseur, un amateur, dans le genre d'une observation simple, un trait de crayon, qui écrase la critique d'art.

Ce soir-là, le Rubens est très belle, parfaite dans le genre batifoleur , très bien distribuée, donc : Hélène Mas. Les couplets qui prolongent le dialogue entre le choeur et Barbe Bleue sont absurdement répétitifs, mais bien calés, joyeux : 'c'est un Rubens', repris sans se fatiguer, qui devient l'autre tube de la soirée.

Sourire à un beau moment, comme une incidente, sur le pouvoir des belles voix : Popolani, le sorcier du roi, savant fou julevernien qui concède, face à un Barbe Bleue qui se réjouit de toutes ces femmes empoisonnées : 'il faut lui rendre justice, il prend tout ça très gaiment...Et puis il a une belle voix'. Ah, alors, c'est bien ça, la morale d'Offenbach (et du IInd Empire) si le ténor a une belle voix, alors, on pardonne à Barbe Bleue, on pardonne ses crimes au tyran.

[Nota : les soutiens institutionnels de l'Opéra de Lyon rechignent depuis peu à leur subvention, de Wauquiez aux écolos de la mairie de Lyon, d'accord là-dessus, irresponsables (et les courtisans s'inclinent, z'an s'inclinent..) La reprise de Barbe Bleue, dans ce cadre, est une recette sûre, dans tous les sens du terme, qui amortit la difficulté présente, l'opérette à succès qui remplit les caisses. Pour ce Barbe Bleue, on souscrit volontiers. Laurent Pelly, une affaire qui marche.]

Vendredi 9 février 2024, Opéra de Paris, Béatrice di Tenda, de Bellini (entrée au répertoire), mise en scène Peter Sellars, ratée et plate, sans élan, pour une partition à tunnels, parcourue cependant d'éclairs bel cantistes que la mise en scène ne parvient pas à fluidifier, ni à justifier. Soirée de déception. C'est un drame de cour et dictature, voyez-vous, alors, on va voir défiler, mouvements de foule sur scène, des troupes en simili cuir et pistolets d'assaut, en avant, en arrière, en avant, pan pan, en arrière, c'est ridicule. L'oppression, comme des allers-retour de soldatesque. Et Béatrice est moche, mal sapée et engoncée de vert : comment comprendre qu'elle suscite passion (jusqu'à la mort) d'Orombello et crime de jalousie de son époux le tyran.

Vite déçu, je prends peu de notes pendant le spectacle : attiré cependant par les premières mesures d'Agnese, amoureuse et jeune soprano à la voix très claire, mais qu'on perd bientôt dans un jeu de scène idiot (isolée dans les cintres, devant sa télé, où elle suit les événements à quoi, nous, on assiste sur scène. Lourdeur qui écrase le personnage, pourtant bien chanté et émouvant au début) je me souviens ensuite que Tamara Wilson (Béatrice) réussit tout de même, vers la fin, à bien supplier et apitoyer, marquée tout de même par son allure de wagnérienne, peu mobile et accablée par la mise en scène qui en fait une victime ensanglantée, sans gloire ni transcendance. Pareil pour Orombello, torturé dès le deuxième acte, effondré, rendu à la seule adultère, dont Peter Sellars oublie qu'il est aussi (et surtout) à la tête d'une insurrection qui gronde.

Dimanche 24 mars 2024, à l'Opéra de Lyon, grande salle : La dame de pique , de Tchaïkovski, mise en scène Timoféi Kouliabine. Direction Daniele Rustioni, très à l'aise avec l'onction et la rondeur romantique de Tchaïkovski, ça s'entend dès l'ouverture où on comprend par la musique tous les contrastes et les antagonismes qui vont faire la pièce : bien/mal, folie de l'amour/enfer du jeu et du calcul social. Direction qui passe très bien, sans rupture, de la lenteur au tumulte : tout au long, et qui sert bien le personnage (ténor, Dmitry Golovnin) d'Hermann pris entre mélancolie et vigueur destructrice. Mais Hermann est, disons, mal présenté : trop vieux, mal attifé, pas séduisant et on ne comprend pas pourquoi la jeune première se prend de passion pour cet homme mur, en proie à sa furie du jeu. Trop vieux également pour croire à la fable romantique des 'trois cartes', secret qui doit lui permettre de triompher au jeu. Mais voix (russe ?) ferme, aux belles notes graves.

Réussite de la mise en scène qui ne cherche pas à tordre le bras au drame historique en costumes ; Saint-Petersbourg, ses bals, ses concerts, ses cafés, est classiquement figuré, sans excès ni parodie. La scène est 'ancien régime', soit tsariste, soit soviétique renvoyés à égalité de regrets : le temps de la légèreté. La nostalgie soviétique, par exemple est rendue par un décor de salle des fêtes d'une maison du peuple, où les jeunesses communistes chantent et dansent, où on projette des portraits avenants du petit père des peuples. Ça se moque, évidemment, mais sans dénaturer ce goût du passé, ni le caricaturer. La clé du bonheur, son secret fabuleux est en effet dans le passé, dans ce très beau personnage (chant de douleur et de regret, peut-être le plus beau moment de la soirée) de la Comtesse (Elena Zaramba) : 'ah ce monde est détestable, quelle époque. On ne sait plus s'amuser.' La comtesse fait entendre avec une grande tristesse, cette mélancolie funèbre qui emporte la Russie moderne [sans insister, on rappelle de Timoféi Kouliabine s'est exilé de Russie dès février 2022, au moment de l'invasion de l'Ukraine...], nostalgie qu'elle chante pour partie en français, ce qui ajoute au trouble (quiconque n'a pas connu l'ancien régime ne sait pas ce qu'est le bonheur, comme on disait...)

Vendredi 15 mars, à la Comédie de Saint-Étienne, salle Jean Dasté, soirée avec Anna, pour Edelweis [France Fascisme], de Sylvain Creuzevault, montage de textes des pires collabos vichystes et pro-allemands, Brasillach, Rebattet, Drieu, Doriot etc...enquillés dans une sorte de farce bouffonne très bien vue, délirante mais grave. Très belle soirée de théâtre, avec Anna, qui est ravie.

Le texte est une enfilade de discours, documentés ou en tous cas qui citent leurs références, et présentés comme tels, à plat, crûment. On passe de l'un à l'autre des ultra collabos, genre passage en revue de l'ignominie. Bien vu du point de vue historique, présenté comme un formidable délire, qui ne cherche pas à expliquer raisonnablement les raisons des uns et des autres : c'est la grande réussite de ce spectacle, bien joué, en se marrant, à fond, dans une sorte de danse macabre. Les comédiens tiennent plusieurs rôles, rassemblant la collaboration dans un seul portrait, un seul ton, uniformisé par leurs éructations. Très bien et rare : la mère de Rebatet, absente de l'histoire d'ordinaire, à la racine 'Action Française' de tout ça. Et, pour les régionaux dans le public, madame Rebatet, odieuse, assure la présence de Moras-en-Valoire, berceau des Rebatet, notaires, etc... Charlotte Issaly joue un Brasillach faussement tranchant et sûr de lui, faible au bout du compte, trouble. Rebatet aussi est joué par une femme. Un effet 'petite gouape' dans les deux cas, efficace.

Peut-être préservé plus que les autres : Céline, joué très toubib de dispensaire, qui les met tous à distance. Il chie sur scène : leur merde. Pour tous : une justification des meurtres à quoi ils appellent, sur fond d'argumentation idéologique : bien obligés, nous luttons contre la décadence et ses agents, juifs bien sûr, mais aussi gaullistes, pétainistes, tous lâches et finalement traitres à l'ordre allemand si nécessaire pour libérer l'Europe. Leur trouille, bien montrée, hurlée : la décadence du beau pays de France.

Très bon théâtre donc, vivant. Dur, cauchemar et grotesque.

[Je dors sur un coin de canapé chez Anna. Levé très tôt et train du retour, parfait bonheur du petit matin, après bon théâtre.]

0 notes

Text

Jean-Claude Brialy and Gérard Blain in Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1959)

Cast: Gérard Blain, Jean-Claude Brialy, Juliette Mayniel, Guy Decomble, Geneviève Cluny, Michèle Méritz, Corrado Guarducci, Stéphane Audran, Paul Bisciglia. Screenplay: Claude Chabrol, Paul Gégauff. Cinematography: Henri Decaë. Production design: Bernard Evein, Jacques Saulnier. Film editing: Jacques Gaillard. Music: Paul MIsraki.

Chekhov's gun plays a major role in Les Cousins, heightening the suspense about who will use it on whom. But the film isn't a suspense thriller, despite Chabrol's admiration for Hitchcock, so much as a deliciously perverse adaption of some classic fables: the country mouse and the city mouse, and the ant and the grasshopper. It also resonates ironically with Balzac's Lost Illusions, the novel that a bookseller (Guy Decomble) allows Charles (Gérard Blain) to "steal" from his shop. In the Balzac novel, a young man from the provinces goes to Paris to seek fame, fortune, and love, and his misadventures wreak havoc on himself and the people he loves. In Les Cousins, country mouse/ant Charles goes to Paris to share an apartment with his cousin, Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy), the city mouse/grasshopper, while both study law. Paul is a somewhat decadent hedonist, who tries to introduce the straiter-laced Charles, who is very much dedicated to his mother back home, to the delights of the city. One of these delights is the promiscuous Florence (Juliette Mayniel), with whom Charles falls in love, only to have things end badly when she chooses to live with Paul instead. Chabrol fills the movie with quirky, somewhat sinister characters, though never turns the film into a clear-cut tale of good vs. evil. Innocence doesn't triumph over cynicism here, though cynicism pays a price, which is what makes Chabrol's film such a grandly satisfying one to watch and to think about afterward. Blain and Brialy (in a suitably Mephistophelean mustache and beard) are brilliant, and the cinematographer, Henri Decaë, gives us a grand evocation of Paris in the 1950s.

0 notes

Photo

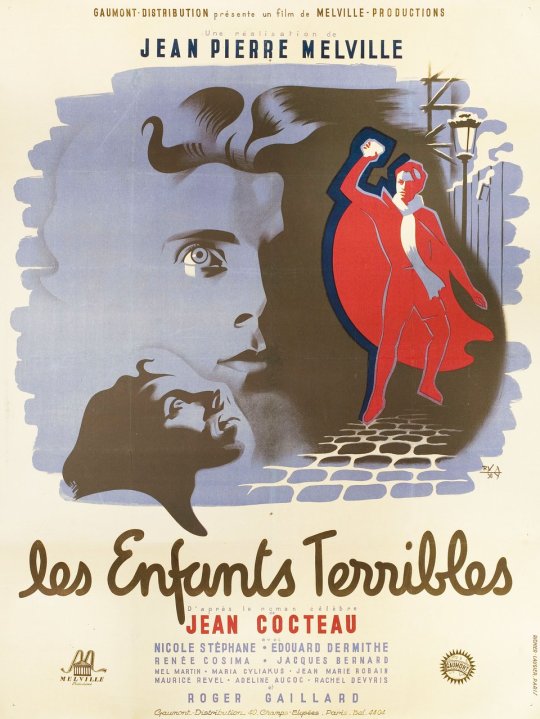

Les enfants terribles (The Terrible Children) (1950) Jean-Pierre Melville

October 3rd 2022

#les enfants terribles#the terrible children#1950#jean-pierre melville#nicole stephane#edouard dermithe#jacques bernard#renee cosima#maurice revel#roger gaillard#adeline aucoc#melvyn martin#jean cocteau#jean cocteau's les enfants terribles

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roger Carel en bonne compagnie

Roger Henri Élie Bancharel dit Roger Carel (1927-2020)

#photo#RIP#roger carel#roger dumas#jean louis trintignant#jean rochefort#Jacques Dufilho#michel galabru#jacqueline maillan#andré gaillard#pierre tornade#michel serrault#benny hill#gérard hernandez#kermit#kermit la grenouille#kermit the frog

19 notes

·

View notes