#Jack Parlett

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

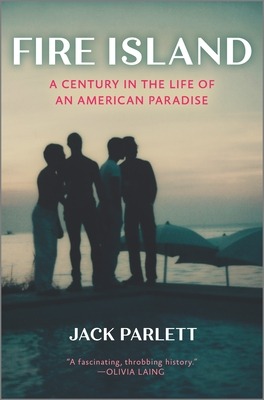

Fire Island: A Queer History by Jack Parlett

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Days of Literary Pride 2023 - June 1

Fire Island: A Century in the Life of an American Paradise - Jack Parlett

0 notes

Text

"Billy Bunter" art, Free Gift issues of top British comics in latest Phil-Comics auction

View On WordPress

#Airfix#Auction News#Billy Bunter#Captain Scarlet#Cracker#Dan Dare#Dinky Toys#downthetubes News#Eagle Days#Fantastic#Free Gifts#George and Lynne#Humour Comics#Jack Kirby#Josep Gual#Reg Parlett#SF Comics#The Hornet#Toby#Valiant

1 note

·

View note

Text

One night this past February, over drinks and moody bar lighting in Brooklyn, Eric Green and his friends were swapping stories of their recent hookups when one mentioned they’d used the app Sniffies to have public sex. A 30-year-old tattoo artist who works in Bushwick, Brooklyn, Green identifies as a bottom, is a frequent user of dating apps, and has an active sex life—only, he’d never heard of Sniffies.

It wasn’t long after that night out, Green was overtaken by “complete and total horniness” while at home, and decided to sign up himself. When he opened the app he was reminded of Google Maps, only instead of restaurants and shopping recommendations, he was inundated with nudes and suggestions for the nearest pump-and-dump. “I expected it to be like Grindr and Jack’d, but after I checked it out I realized it was super accessible,” Green says, referencing two other popular queer hookup platforms. “More accessible than any other app.”

Access is Sniffies’ main selling point. A map-based cruising platform for men of all sexual identifications (gay, bi, DL, and straight-curious—yes, you read that right), Sniffies has become something like an adults-only Disneyland for queer men interested in sex-positive, no-strings-attached casual encounters. “We really focus on in-the-moment connections,” says Eli Martin, the company’s chief marketing officer and creative director. “On other apps, it’s not always clear what people’s intentions are—some people want to find a boyfriend, others just want to look around—but on Sniffies, we try to make it clear that people are fulfilling their sexual desires and fetishes.”

Sniffies is not your typical dating app, or a dating app at all, really. In lieu of the typical song and dance on Tinder or Bumble, where conversations are bogged down in endless chatter that often never materializes into an IRL meeting, on Sniffies you can anonymously browse a map of guys looking for sex with other guys. Along with web-apps BKDR (short for backdoor), Motto, and Doublelist (think a more streamlined Craigslist personals), it has reignited an appeal in cruising culture that for so long had been taboo, even among certain queer circles, for fear of acceptance or health concerns.

“Destigmatizing casual sex has been our biggest hurdle in general,” says Martin. “It’s been ingrained in us to be monogamous, but we should have this sexual freedom. Cruising doesn’t have to be seedy or something that only happens in back alleys.” Thankfully, he says, that’s changing. “In the last couple of years, we’ve been able to enjoy it more without as much judgment, but it was still hard on day one, because I was like, how do we create an app that’s [not only cool] but going to continually push people to engage in?”

Launched in 2018, Sniffies was the brainchild of former Seattle-based architect Blake Gallagher. A problem-solver by nature, Gallagher was fascinated by the way urban environments influence sexual interactions. He wanted to better augment natural human connection in public spaces, and decided to implement a map feature and geolocation technology as the basis for Sniffies—tapping into what author Jack Parlett calls “the democratic potential of cruising.” Gallagher first tested his idea in Seattle and, with the help of his brother Grant, a programmer, slowly built Sniffies into what it is today—a “cruising app for the curious” with an increasing global reach.

“We really push for the physical aspect of getting off your phone and out and about,” Martin says. And it’s paying off. According to data shared with WIRED, the US cities that see the most action—that is, the horniest cities—are Los Angeles, New York, Dallas, Chicago, and Atlanta. (These figures are based on the highest number of sessions within a geographic area.) London saw a 475 percent growth in usership from 2022 to 2023, and Vancouver is Sniffies’ most discreet city.

Green says he uses the app twice a week “if I’m actually going to meet up with somebody, but I will go on there and scroll every so often.” (His last name was changed to protect his privacy.) According to the company, the average Sniffies user identifies as vers (25.6 percent of total users), has a penis size of 6.67 inches, prefers to cruise a park, restroom, or a residential tower of some sort, is into edging and cum play, and is most likely having sex on Mondays. Since joining, Green describes his time on Sniffies as “kinda calm,” compared to his friends. The encounters he has had, he says, have been “from apartment to apartment, nothing outside or in the gym.”

BKDR is another rising player among the burgeoning world of queer cruising apps. Eric Silverberg says users on Scruff and Jack’d—sister apps to BKDR (all three are owned by Perry Street Software)—were identifying “a clear desire for a platform that prioritized sexual expression and sex.” Cruising has occurred for centuries, he says, and an app like BKDR is a “direct, no-nonsense product that allows people to get on and get off in a very literal sense.”

The demand certainly seems to be there—and the potential for such apps is only growing. Although BKDR launched less than a year ago, it has already expanded to Latin America and Europe. “It’s early days for us, but over 1 million people have visited BKDR in the past month,” Silverberg tells me, adding, “We think it will be the biggest product in our portfolio.”

Growth brings its own set of problems, however. A recent Reddit post detailed how a more conservative kind of user now inhabits the Sniffies. “Now that [the app] is getting really popular in some places there are a ton of guys on the map in my area and most of them are just there to waste your time. I'm looking for [a] hookup right now,” user @curiousFriend2 wrote. “Sniffies used to cater to lowkey guys and even some cumdumps and the more sleezy side, but now the Grindr crowd [has] come in and a lot of them are not even into those things and publicly announce it.”

Sniffies took off following the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020, and Martin believes the isolation of the pandemic led to users being more open-minded about cruising. “People’s mindset changed to realize that they want to take advantage of the moment,” he says.

That’s mainly what Green is after most days, though he says he tries not to use Sniffies as a crutch. “It’s cool to go on during my downtime—late at night or early in the morning,” he says, “because I actually have stuff to do, and I don’t want to throw my day looking for dudes,” he says, before adding that “if you’re solely looking for fun,” it’s unbeatable.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonfiction Thursday: LGBTQIA+ History Month

The LGBTQ+ History Book by DK Publishing

Exploring and explaining the most important ideas and events in LGBTQ+ history and culture, this book showcases the breadth of the LGBTQ+ experience. This diverse, global account explores the most important moments, movements, and phenomena, from the first known lesbian love poetry of Sappho to the Kinseys' modern sexuality studies, and features biographies of key figures from Anne Lister to Allen Ginsberg.

The LGBTQ+ History Book celebrates the victories and untold triumphs of LGBTQ+ people throughout history, such as the Stonewall Riots and first transgender surgeries, as well as commemorating moments of tragedy and persecution, from the Renaissance Italian “Night Police” to the 20th century “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy. The book also includes major cultural cornerstones - the secret language of polari, Black and Latinx ballroom culture, and the many flags of the community - and the history of LGBTQ+ spaces, from 18th-century “molly houses” to modern “gayborhoods.”

The Gay Revolution by Lillian Faderman

The fight for gay and lesbian civil rights - the years of outrageous injustice, the early battles, the heart-breaking defeats, and the victories beyond the dreams of the gay rights pioneers - is the most important civil rights issue of the present day. In “the most comprehensive history to date of America’s gay-rights movement” (The Economist), Lillian Faderman tells this unfinished story through the dramatic accounts of passionate struggles with sweep, depth, and feeling.

The Gay Revolution begins in the 1950s, when gays and lesbians were criminals, psychiatrists saw them as mentally ill, churches saw them as sinners, and society victimized them with hatred. Against this dark backdrop, a few brave people began to fight back, paving the way for the revolutionary changes of the 1960s and beyond. Faderman discusses the protests in the 1960s; the counter reaction of the 1970s and early eighties; the decimated but united community during the AIDS epidemic; and the current hurdles for the right to marriage equality.

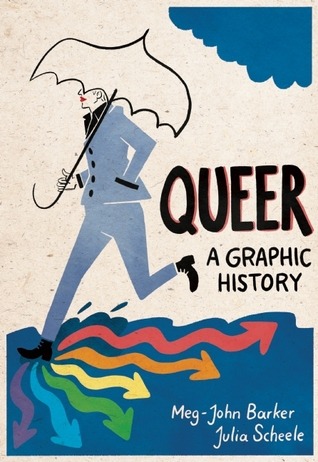

Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker & Jules Scheele

Activist-academic Meg John Barker and cartoonist Julia Scheele illuminate the histories of queer thought and LGBTQ+ action in this groundbreaking non-fiction graphic novel. A kaleidoscope of characters from the diverse worlds of pop-culture, film, activism and academia guide us on a journey through the ideas, people and events that have shaped 'queer theory'.

From identity politics and gender roles to privilege and exclusion, Queer explores how we came to view sex, gender and sexuality in the ways that we do; how these ideas get tangled up with our culture and our understanding of biology, psychology and sexology; and how these views have been disputed and challenged.

Along the way we look at key landmarks which shift our perspective of what's 'normal', such as Alfred Kinsey's view of sexuality as a spectrum between heterosexuality and homosexuality; Judith Butler's view of gendered behavior as a performance; the play Wicked, which reinterprets characters from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz; or moments in Casino Royale when we're invited to view James Bond with the kind of desiring gaze usually directed at female bodies in mainstream media.

Fire Island by Jack Parlett

Fire Island, a thin strip of beach off the Long Island coast, has long been a vital space in the queer history of America. Both utopian and exclusionary, healing and destructive, the island is a locus of contradictions, all of which coalesce against a stunning ocean backdrop.

Now, poet and scholar Jack Parlett tells the story of this iconic destination - its history, its meaning and its cultural significance - told through the lens of the artists and creators who sought refuge on its shores. Together, figures as divergent as Walt Whitman, Oscar Wilde, James Baldwin, Carson McCullers, Frank O'Hara, Patricia Highsmith and Jeremy O. Harris tell the story of a queer space in constant evolution.

Transporting, impeccably researched and gorgeously written, Fire Island is the definitive book on an iconic American destination and an essential contribution to queer history.

#lgbtqia history#nonfiction#nonfiction books#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 reads in 24

Hey @suseagull04 thanks for tagging me in this! You KNOW books are my favourite thing in the world, and I'm kind of into the idea of writing this list and giving myself a little accountability in tackling the massive TBR pile that lives by my bed 😬. Maybe I'll update it and tick off the ones I've finished as I go.

Here we go then, 24 books I want to read in 2024 (in no particular order):

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, by Silvia Moreno-Garcia (ok, I started this last night but I’m only 10 pages in, so it’s going on the list)

Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, by Benjamin Alire Sáenz

A Power Unbound, by Freya Marske

Fire Island, by Jack Parlett

News from Nowhere, by William Morris

A Darker Shade of Magic, by V. E. Schwab

Tipping the Velvet, by Sarah Waters

Wolfsong, by TJ Klune

Boyfriend Material, by Alexis Hall

The Testaments, by Margaret Atwood—which means rereading👇

The Handmaid’s Tale, by Margaret Atwood

The Silence of the Girls, by Pat Barker

Her Majesty’s Royal Coven, by Juno Dawson

Hunger, by Roxane Gay

Beautiful World, Where Are You?, by Sally Rooney

Love Marriage, by Monica Ali

Captive Prince, by C.S. Pascat

The Ruin of a Rake, by Cat Sebastian

Friday I’m in Love, by Camryn Garrett

Trouble, by Lex Croucher

Olive Kitteridge, by Elizabeth Strout

A Nobleman’s Guide to Seducing a Scoundrel, by KJ Charles

The Charm Offensive, by Alison Cochrun

Uprooted, by Naomi Novik

BONUS: The Pairing, by Casey McQuiston. It's not on the pile yet, but it will be.

Ok, some of you I know are big readers but I'm not sure about everyone so tagging @cha-melodius @ships-to-sail @stereopticons @missgeevious @nontoxic-writes @kiwiana-writes @indomitable-love @14carrotghoul @zwiazdziarka @orchidscript but if I haven't tagged you and you also love reading PLEASE do this and tag me so we can chat books! 😘

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

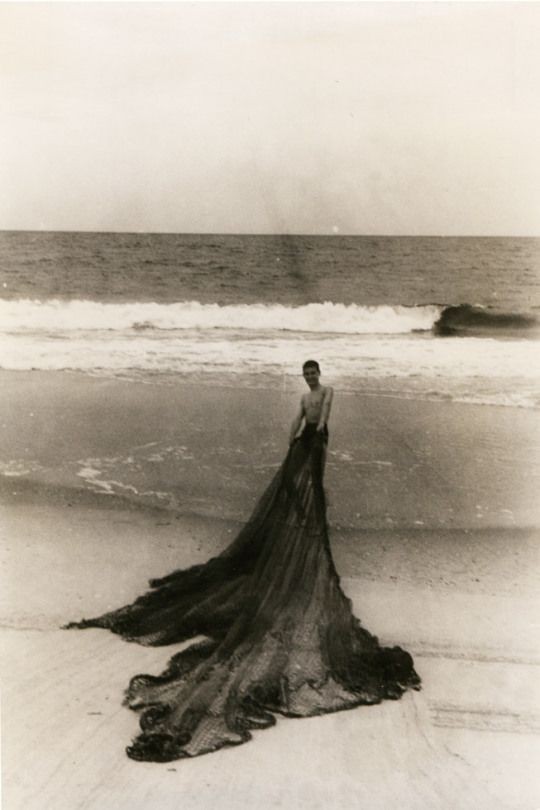

"But the Pines, in that era, had also become a graveyard of lost friendships, as gay men far younger than Windham were dying of AIDS at an alarming rate. The decimation of the island's gay community shed light on the fragility of the past, on how easily tales and stories could die with their protagonists. Whether consciously or not, Windham's deep dive into a past he shared with people who were now dead, a gay literary world that had now disappeared, was a political act, at a time when bearing witness and remembering had gained a new urgency."

Donald Windham photographed by Jared French, Fire Island 1942

Fire Island, A Queer History by Jack Parlett

#queer history#queer photography#queerness#gay history#fire island#donald windham#lgbtpride#lgbt#lgbtq community#lgbt history#lgbtq history

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

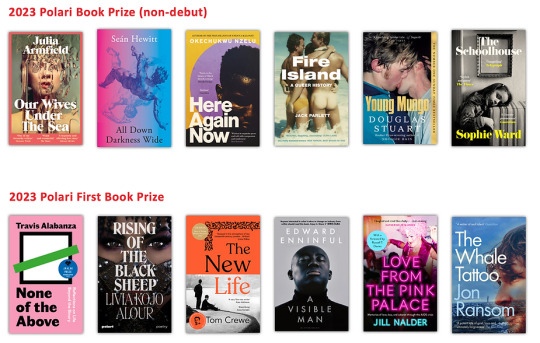

2023 POLARI PRIZE SHORTLISTS CELEBRATE QUEER STORIES THAT “ENTERTAIN, ENRICH AND INSPIRE”

Memoir, non-fiction, and critically acclaimed literary fiction from a mixture of independent presses and larger publishers dominate the dynamic shortlists for this year’s Polari Prize and Polari First Book Prize, the UK’s only dedicated awards for LGBTQ+ literature.

“The quality of long-listed titles this year was so exceptionally high, a number of much-loved titles didn’t make the shortlists” said Paul Burston, founder of the prizes. “Taken together, this year’s shortlists are a powerful testament to the quality and diversity of LGBTQ+ writing in the UK and Ireland today. From dazzling debuts to writers delivering on their earlier promise and really upping their game, these are books to entertain, enrich and inspire.”

Powerful stories of resilience and resistance are the focus of this year’s Polari First Book Prize. None

of the Above by Travis Alabanza (Canongate) is an electric memoir exploring life outside the gender boundaries imposed on us by society. Edward Enninful’s A Visible Man (Bloomsbury) also makes

the list, detailing how the man behind British Vogue has built an extraordinary life; more memoir makes an appearance with It’s A Sin’s Jill Nader and her heartbreaking and eye-opening memoir, Love from the Pink Palace (Wildfire). Fiction titles spotlighted in this category are Jon Ransom’s complex and transporting The Whale Tattoo (Muswell Press) and Tom Crewe’s historical debut novel, The New Life (Chatto & Windus). Rounding up the Polari First Book Prize is Livia Kojo Alour with Rising of the Black Sheep, the only poetry title in the shortlists.

Poet Sophia Blackwell, Polari First Book Prize judge, said:

“The shortlist is full of fearless, moving and original stories. Full of insights about how the authors came to occupy their particular places in the world, they also set out hopeful, ambitious visions for the future.”

Rachel Holmes, Polari First Book Prize judge, said: “Look no further for this year’s quintessential queer bookshelf to illuminate and inspire the approaching autumn evenings, winter weekends and festive season. There’s a beautiful, brilliant read here for all the queer family. Comfortably encompassing diverse genres and multiple points of view, fledgling emerging talent and celebrated household names, this year’s shortlist bravely re-empowers the past, interprets the present, and boldly imagines the future.”

Adam Zmith, Polari First Book Prize judge, said: “The titles on the shortlist for this year’s Polari First Book Prize wrestle with history and the present moment in engaging and empathetic ways. I loved reading these books, and feeling the queer power in them and their authors’ visions.”

Karen McLeod, Polari First Book Prize judge, said: “This shortlist is dynamic, expansive, moving and truly novel (is it too late to request a box of tissues as a rider?) I am proud we have such a diverse and emotionally intelligent set of queer voices being published today.”

Queer utopias, further memoir and exquisite prose feature in the Polari Book Prize shortlist with Jack Parlett’s Fire Island (Granta), a vivid hymn to an iconic destination, being selected and poet Seán Hewitt turns his hand to memoir in All Down Darkness Wide (Jonathan Cape). A varied spread of fiction completes the shortlist with Julia Armfield’s deep sea love story Our Wives Under the Sea, Okechukwu Nzelu’s tender study of family and grief Here Again Now (Dialogue Books), Sophie Ward’s gripping thriller The Schoolhouse (Corsair) and concluding the list is Douglas Stuart’s heartbreaking Young Mungo (Picador).

Joelle Taylor, Polari Book Prize judge, said: “This year’s Polari Prize shortlist reflects the complexities of contemporary LGBT+ lives in work that is nuanced, expansive, intimate and strange. History, futurism, crime, poetic memoir, and social commentary collide to create rich narratives that rewrite us even as we read.”

VG Lee, Polari Book Prize judge, said: “We have a strong and diverse shortlist for the Polari Prize. These are books that will appeal to many. They are that odd word, “keepers”- books to return to.”

Suzi Feay, Polari Book Prize judge, said: “This year’s shortlist highlights the sheer range and power of LGBTQ+ writing across all genres. Passionate, stylish and outspoken, these are voices to haunt and seduce. Our six choices deserve the widest readership.”

Chris Gribble, Polari Book Prize judge, said: “This year’s Polari Prize shortlist lays out the joys, challenges and complexities of contemporary and historical LGBTQ+ lives in a brilliant array of fiction and non-fiction that will leave no one in any doubt that our stories are worthy of their places on every book shelf and in every library. These writers are working at the peak of their powers and if you haven’t read their work yet, you have a real treat in store.”

2023 Polari Book Prize (non-debut)

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield (Picador)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt (Jonathan Cape)

Here Again Now by Okechukwu Nzelu (Dialogue Books) Fire Island by Jack Parlett (Granta Books)

Young Mungo by Douglas Stuart (Picador)

The Schoolhouse by Sophie Ward (Corsair)

2023 Polari First Book Prize

None of the Above by Travis Alabanza (Canongate Books)

Rising of the Black Sheep by Livia Kojo Alour (Polari Press)

The New Life by Tom Crewe (Chatto & Windus)

A Visible Man by Edward Enninful (Bloomsbury)

Love from the Pink Palace by Jill Nalder (Wildfire)

The Whale Tattoo by Jon Ransom (Muswell Press)

Established in 2011, The Polari First Book Prize is awarded annually to a debut book that explores the LGBTQ+ experience, and has previously been won by writers including Kirsty Logan, Amrou Al-Kadhi, Mohsin Zaidi and last year’s winner Adam Zmith, for his keenly-researched history of poppers, Deep Sniff.

Established in 2019, The Polari Book Prize awards an overall book of the year, excluding debuts, and previous winners include Andrew McMillan (Playtime), Kate Davies (In At the Deep End), Diana Souhami (No Modernism Without Lesbians) and last year’s winner Joelle Taylor for her remarkable collection C+nto & Othered Poems which explores butch lesbian counterculture in London.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

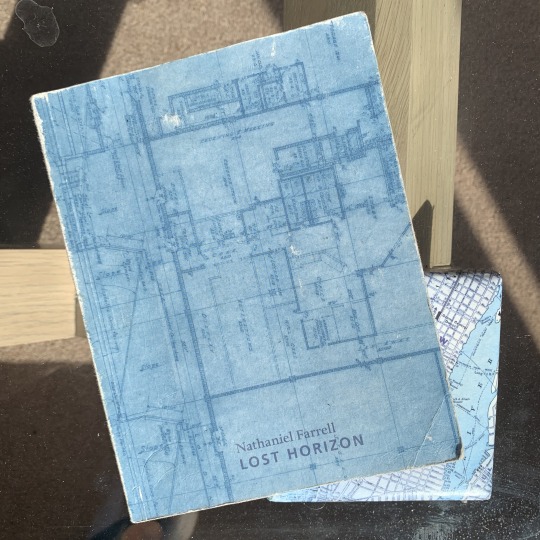

(REVIEW) Lost Horizon by Nathaniel Farrell

In this review, Jack Parlett ventures through the avenues, grooves and colliding landscapes, fantasies and libidinal economies of Nathaniel Farrell’s Lost Horizon (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019).

> Nathaniel Farrell’s long poem Lost Horizon (2019), which takes as its subject the space of the retail utopia, makes me think of a lot of things. Which is to say that its sense of breadth and abundance – packed full of things and images, traversing vast distances across different landscapes – had me grasping for other reference points, for affinities that might suggest ways of reading it. The pile-up of the opening lines, scattered across the page, offers a glimpse into the ways this poem can get you lost:

The fountain full of coins the smell of pretzels, print, perfume

formaldehyde in fabrics

brass rails down stairwells rebar in the pillars

the underground parking structure – Roman alphabet

Arabic numerals –

(Farrell 2019: 1)

> The mall, scented with the churn of Auntie Anne’s pretzels (say) and the potent fragrances of a nearby department store, is rendered throughout the poem as an archaeological surface, as though the poet’s task were one of excavation. Lost Horizon reminds me, in this sense, of an Anselm Kiefer painting; a maximalist collage blending the industrial and the pastoral, foregrounding the dimensionality of objects that appear ‘found’ within the landscape of the work, like the unsettling use of spindly wires and sticks the painter is known for. Farrell, too, is interested in exteriorising the subterranean, the things that glimmer and protrude, like the ‘coins’ emanating from beneath the water of the fountain, like the chemical compounds found in our clothes. His is a multi-storeyed work, finding ancient linguistic systems in car parks, conferring the quotidian spaces of late capitalism with the dignity of the palimpsest.

> But Farrell’s poem does not settle upon one groove. It unfolds in strange and wrong-footing ways. Although this opening passage would seem to suggest a logic of succession, a list of things you might expect to find in a shopping mall, with an associative momentum driven forward by alliteration, the poem’s larger scheme is one of randomness, a yoking together of any number of images and textures. (My personal favourite: ‘Avocado. TV as diorama or diocese catfish farm trout hatchery.’) (27). This fragmented structure speaks back to the form of the Surrealist catalogue, or to experiments in automatic writing, and renders them in a distinctly American vernacular, like the New York melee of Frank O’Hara’s long 1953 poem Second Avenue or, more recently, Geoffrey G. O’Brien’s 2011 work Metropole (minus the strict iambic rules.)

> Yet where Second Avenue seems to stage a representational gag – in what sense is this poem, characterised by lines like ‘Butter. Lotions. Cries. A glass of ice’ (O’Hara 1995: 149) ‘about’ Second Avenue itself? – the abstraction of Farrell’s purview is already made explicit in his title. Lost Horizon is a work in search of a potentiality that has already been lost, and it goes looking for it in all kinds of places: shopping malls, forests, multiplexes, highways, locales suspended in the poem’s veering between the vitality of the artificial and the natural realm to which it shall one day return. Where a ‘rebarbative’ work like Second Avenue, in Andrea Brady’s words, recoils ‘from sentimentality but also from the reader’ (Brady 2010: 60), Farrell’s poem does the opposite. It homes in upon the way that sentiment might inhere in the spaces and materials of consumption and the faded spectacles of capital. Perhaps this is why, beyond any of the more high-minded comparisons it invites, Lost Horizon makes me think most of all of the town I grew up in.

> It feels a little parochial to compare the scale of Farrell’s Americana with a single town in Buckinghamshire. (He writes in the Acknowledgments that the project ‘emerged from road travel’ and draws upon the imagery of places including ‘St. Louis and Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit, Minneapolis, Cleveland, Kansas City, Pittsburgh, and Fort Wayne’.) Yet shopping malls trade, the poem suggests, in incongruity; they flatten space and time, incorporate the urban, the pastoral and the global, as if the whole world might be incorporated under their ceilings. I realised in navigating this poem that so much of my sense of America, and Americanness as a kind of distant and glamorous imaginary, was mediated through my childhood in Milton Keynes. Milton Keynes was, after all, developed with reference to the layout of American cities.

> The area known as Central Milton Keynes (or ‘CMK’) was conceived in the mid-seventies as part of the recently created ‘new town’ in Buckinghamshire, and was officially opened by Margaret Thatcher in 1979. Although ‘CMK’ is a municipal designation – a name for the central zone of the larger Milton Keynes area – it is predominantly a business and retail district. Laid out on a grid, CMK sits somewhere between the ‘downtown’ area of an American city and the out-of-town shopping mall; an assemblage of shopping centres, office buildings and industrial parks, characterised by its distinctive glass-and-steel buildings and an infamous number of roundabouts. Like many British ‘new towns’, Milton Keynes was created with both pragmatic and idealistic aims in mind. On the one hand, it was an overspill project providing an outlet for London’s rising and congested population. On the other, it was to be a new frontier both socially and architecturally; an automobile haven merging green space with the imposing surfaces of the modern city. Today, it looks both futuristic and dated. Or rather, it looks like what the future was once supposed to look like.

> When I tell people I grew up in and around Milton Keynes, it usually prompts one of two responses. The first, most frequent and predictable, is a kind of apologetic nod, a nod to MK’s associations in the national imaginary as a uniquely naff, soulless place. The other (more generous) reaction is a kind of keen and outsize enthusiasm, prompting a conversation about the town’s architectural significance or its peculiar place in British local history as an experiment of urban planning. (There’s also, sometimes, outright judgment, as when on my first day of university a private schoolboy told me that ‘when I think of Milton Keynes I think of scum.’). My feelings about the place fall somewhere in the middle – I’m defensive of it in the face of snobbery, but I also think that the people who find it an area of intellectual interest probably didn’t grow up there. Until the opening of the recently re-developed Milton Keynes Gallery, which was reported widely in the national press, CMK lacked a culture of its own, and it still remains best known as a cornucopia of brand names and chain restaurants.

> And yet I can’t pretend that some part of me doesn’t kind of love it. Farrell’s work pays attention to the embarrassment one might feel about being from a place like Milton Keynes, or rather the embarrassment in our attachments to such a place. I still desire to rediscover the uniquely artificial pleasures of the shopping mall. Against my better judgments, I find myself beguiled again by CMK’s performance of grandeur, its strange radiance. Or perhaps its that my memories of childhood and adolescence are shot through, like an off-brand Lorde song, with its suburban framework, its constellation of uniquely named places like The Point, a red steel pyramid housing the UK’s first multiplex cinema when it opened in 1985, or the pastoral-sounding Midsummer Place, an extension of the shopping centre built around an oak tree, which people still refer to today as the ‘new bit.’ (It was opened at the start of the millennium and has been bought out by the Intu franchise. The tree is no more.)

> The speaker of Lost Horizon similarly figures the retail landscape as a site of affective and libidinal attachments, less a utopic horizon than a space where experience is packaged and backlit, where material capitalism might dupe us into utopic thinking, where you can hear ‘the beat of an unmoored heart in the duty-free shop’ (Farrell: 70). (The term retail therapy is particularly apt.) This speaker has a mobile erotic attention; reflects on the bulge of a male model, spots ‘a sign for Hooter’s at the Colonial Williamsburg exit / the owl’s eyes made to look like nipples’ (24) and appears to cruise, ‘wait[ing] at the bathrooms; / they smell of feces and orange cleanser / Yankee Candle’ (23). Nature, after all, will make its return, and the most pristine spaces must co-mingle with muck, human and otherwise. An ominous refrain towards the beginning of the poem - ‘A cellphone glows in a back pocket’ (9) - signals the mall’s impending obsolescence, its succumbing to the space of the virtual, and this in turn informs the poem’s ecological fixation, its avalanche of natural elements and catastrophic tableaux. Because this is what happens to shopping malls, eventually, as shown in the work of photojournalist Seph Lawless. Lawless’s portraits of abandoned shopping malls in economically precarious parts of America, malls now overgrown with vegetation, look post-apocalyptic, like a contemporary sci-fi iteration of the way Walter Benjamin conceptualised the Parisian arcades of the nineteenth century; as repositories, in part, for the lost dreams of prosperity.

> The shopping area of Central Milton Keynes is now Grade II-listed by Historic England, and it is renowned for its extensive greenery, its line of trees that populate the grid. (The area as a whole boasts 22 million trees and shrubs.) The integration of the green and sub(urban) landscape is something that makes the centre of Milton Keynes more desirable and sustainable, a nod to the land’s past. But you could look at it another way; not as a symbol of origin, but of man-made transience. Whatever shiny promises the retail utopia makes, it is built, Farrell’s dizzying poem suggests, to one day succumb to an unknowable horizon, where the trees will be ‘all that remain of home’ (3).

References:

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press)

Brady, Andrea. 2011. ‘Distraction and Absorption on Second Avenue.’ Frank O’Hara Now: New Essays on the New York Poet (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press). 59-70

Farrell, Nathaniel. 2019. Lost Horizon (Ugly Duckling Presse)

O’Brien, Geoffrey G. 2011. Metropole (Berkeley: University of California Press)

O’Hara, Frank. 1995. Collected Poems (Berkeley: University of California Press)

~

Lost Horizon is now available via Ugly Duckling Presse.

~

Text and Image: Jack Parlett

Published: 19/6/20

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I'd consumed enough gay literature and gallows humor to think that my issues were merely part of a package deal. A problem drinker with disordered eating habits? So far, so gay, I though. I looked at myself in the mirror, a man in his early twenties, and saw an identity defined by a lack, and a need to fill it. Drinking gave me a unique kind of confidence in nightlife spaces, numbing and sharpening simultaneously. It seemed to stave off whatever alienation I felt in bars or on dance floors (or inhibitions at the prospect of dark back rooms).

Jack Parlett from Fire Island: A Century Of An American Paradise

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blackjack History

The current popularity of blackjack arose from the tempting possibility that players can gain an advantage and cheat the casino. From Dr. Edward O. Thorp's bestselling book, Beat the Dealer, dramatically increased the skill level and the number of blackjack players in the casino. Blackjack has been, for almost 50 years, one of the favorite casino games of mathematicians and analysts. More has been written about blackjack than any other casino game. Before the expansion of online poker, blackjack was a much more popular topic for analysis than poker.

Despite all the analysis, most of those who write about blackjack have paid little attention to the history of blackjack. In 2006, the main blackjack expert Arnold Snyder, in "The Big Book of Blackjack" (The Big Book of Blackjack) by Cardoza Publishing, investigated the origins and games that preceded blackjack. David Parlett, a British author and inventor of games, also made numerous online and book publications about the history of blackjack.

Blackjack includes the following features: deck of cards, player versus dealer, winner determined by the numerical value of the cards. You can play Blackjack at our official site right now.

Blackjack history: early years The first game with those elements was the Spanish game called Blackjack (21). Miguel de Cervantes, better known as Don Quijote, wrote Rinconete y Cortadillo, which was published as one of his twelve exemplary novels in 1613. A gambling game called "Ventiuna" appears in written works dating back to approximately 1440 (although there are several unrelated games that are called the same).

In England, there was a variant of this game called bone ace during the 17th century. In the history of Cervantes and in "bone ace", as described by Charles Cotton in The Complete Gamester (1674), an ace can be worth one or eleven. A French predecessor of blackjack called quinze (15) first appeared in the sixteenth century and was popular in the casinos of France in the early nineteenth century. An Italian card game called sette e mezzo (seven and a half) was played at the beginning of the 17th century. The "sette and mezzo" included a deck of 40 cards (not including the eight, nine or ten). The remaining cards corresponded to their numerical value; the figures were worth half.

In Belgium, another French game, trente-et-quarante (30 and 40), was also played at the Spa Casino in 1780. Unlike most of these early games, in the "Trente-et-quarante", the house it was banking, that is, the casino played against the players, winning or paying the bets they made. This game was also the first version that offered an insurance bet.

The rules of modern blackjack came together in the French game vingt-un (or Vingt-et-un "21") in the mid-18th century. Among the enthusiasts who promoted the game in France in the late 1700s and early 1800s were Madame Du Barry and Napoleon Bonaparte.

Blackjack history: from the 19th to the 21st century. In the United States in the 19th century, the casinos finally adopted two rules that made the game more favorable for players: they could see one of the cards of the dealer, and the dealer had to get hands of 16 or less and stand with 17 or more At the beginning of the 20th century, the game became better known as blackjack due to a promotion (which was briefly tested and discarded in the long run) that consisted of paying a bonus if the player added 21 with the ace of spades and a black jack (jacks of clover or spades).

Following the popular academic research of Dr. Thorp and subsequent players and analysts, blackjack became the most popular board game in casinos. Although the casinos benefited from the development of the basic strategy and card counting, they have generally advised against the practice. Although numerous court rulings have established that counting cards is not a way of cheating, casinos in most jurisdictions have the right to prohibit the entry of players for any reason. Private casinos also modify the rules of blackjack (which sometimes differ from one table to another): different amounts of decks, different decks of decks, the house asks for a card or is planted with a soft 17, limits to divide or fold, and possibility or inability to give up.

In books like "The Big Player" (The Big Player, 1977) by Ken Uston and Bringing Down the House (2002) by Ben Mezrich, the fortunes that won (and sometimes lost) teams of card counters in blackjack are described. Mezrich's book became the famous movie 21.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Comic art by "Scream Inn" creator Brian Walker and other humour comic greats set to go under the hammer

Comic art by “Scream Inn” creator Brian Walker and other humour comic greats set to go under the hammer

The Interiors auction at Bristol’s Clevedon Salerooms is a regular and eclectic sale featuring a great range of items – and among those on offer this week is a selection of art from the estate of comic artist Brian Walker, who died last year, best known for his work on Beano, The Dandy, and Whizzer and Chips. One of his best-known and most loved strips was “Scream Inn” which first appeared…

View On WordPress

#Auction News#Big Daddy#Black Bob#Brian Walker#Buster#Camberwick Green#Clevedon Salerooms#downthetubes News#Fantasia#Figures#Frankie Stein#Humour Comics#Jack Prout#Mike Lacey#Reg Parlett#Robert Harrop#Robert Nixon#Roy Wilson

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gin Rummy - Two Player Card Games

Gin Rummy is one of the most popular forms of rummy. The game is generally played by two players, each receiving ten cards. Here is an article by David Parlett on the History of Gin Rummy, which was originally published on the Game Account site.

Note: I have been told that among some players the name Gin Rummy in fact refers to not to the game described below, but to the game which is called 500 Rum on this web site.

We would like to thank the following partner sites for their support:

Adda52 Rummy offers live, multiplayer 13 and 21 Card Indian Rummy on the web and Android phones and tablets. It is owned by Gaussian Networks and was registered in 2012.

The affiliate company Raketech was founded in 2010 by professional poker players Erik Skarp and Johan Svensson. They acquired Casinofeber.se in 2018 which is a leading casino comparison portal in Sweden. It is now edited by Daniel Stenlök in Gothenburg, Sweden.

The Deck One standard deck of 52 cards is used. Cards in each suit rank, from low to high:

Ace 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jack Queen King. The cards have values as follows:

Face cards (K,Q,J) 10 points Ace 1 point Number cards are worth their spot (index) value. The Deal The first dealer is chosen randomly by drawing cards from the shuffled pack - the player who draws the lower card deals. Subsequently, the dealer is the loser of the previous hand (but see variations). In a serious game, both players should shuffle, the non-dealer shuffling last, and the non-dealer must then cut.

Each player is dealt ten cards, one at a time. The twenty-first card is turned face up to start the discard pile and the remainder of the deck is placed face down beside it to form the stock. The players look at and sort their cards.

Object of the Game The object of the game is to collect a hand where most or all of the cards can be combined into sets and runs and the point value of the remaining unmatched cards is low.

a run or sequence consists of three or more cards of the same suit in consecutive order, such as club4, club5, club6 or heart7, heart8, heart9, heart10, heartJ. a set or group is three or four cards of the same rank, such as diamond7, heart7, spade7. A card can belong to only one combination at a time - you cannot use the same card as part of both a set of equal cards and a sequence of consecutive cards at the same time. For example if you have diamond7, spade7, heart7, heart8, heart9 you can use the heart7 either to make a set of three sevens or a heart sequence, but not both at once. To form a set and a sequence you would need a sixth card - either a club7 or a heart10.

Note that in Gin Rummy the Ace is always low. A-2-3 is a valid sequence but A-K-Q is not.

Play A normal turn consists of two parts:

The Draw. You must begin by taking one card from either the top of the stock pile or the top card on the discard pile, and adding it to your hand. The discard pile is face up, so you can see in advance what you are getting. The stock is face down, so if you choose to draw from the stock you do not see the card until after you have committed yourself to take it. If you draw from the stock, you add the card to your hand without showing it to the other players. The Discard To complete your turn, one card must be discarded from your hand and placed on top of the discard pile face up. If you took the top card from the discard pile, you must discard a different card - taking the top discard and putting the same card back in the same turn is not permitted. It is however legal to discard a card that you took from the discard pile in an earlier turn. For the first turn of the hand, the draw is done in a special way. First, the person who did not deal chooses whether to take the turned up-card. If the non-dealer declines it, the dealer may take the card. If both players refuse the turned-up card, the non-dealer draws the top card from the stock pile. Whichever player took a card completes their turn by discarding and then it is the other player's turn to play.

Knocking You can end the play at your turn if, after drawing a card, you can form sufficient of your cards into valid combinations: sets and runs. This is done by discarding one card face down on the discard pile and exposing your whole hand, arranging it as far as possible into sets (groups of equal cards) and runs (sequences). Any remaining cards from your hand which are not part of a valid combination are called unmatched cards or deadwood. and the total value of your deadwood must be 10 points or less. Ending the play in this way is known as knocking, presumably because it used to be signalled by the player knocking on the table, though nowadays it is usual just to discard face down. Knocking with no unmatched cards at all is called going gin, and earns a special bonus. (Note. Although most hands that go gin have three combinations of 4, 3 and 3 cards, it is possible and perfectly legal to go gin with two 5-card sequences.)

A player who can meet the requirement of not more than 10 deadwood can knock on any turn, including the first. A player is never forced to knock if able to, but may choose instead to carry on playing, to try to get a better score.

The opponent of the player who knocked must spread their cards face-up, arranging them into sets and runs where possible. Provided that the knocker did not go gin, the opponent is also allowed to lay off any unmatched cards by using them to extend the sets and runs laid down by the knocker - by adding a fourth card of the same rank to a group of three, or further consecutive cards of the same suit to either end of a sequence. (Note. Cards cannot be laid off on deadwood. For example if the knocker has a pair of twos as deadwood and the opponent has a third two, this cannot be laid off on the twos to make a set.)

If a player goes gin, the opponent is not allowed to lay off any cards.

Note that the knocker is never allowed to lay off cards on the opponent's sets or runs.

The play also ends if the stock pile is reduced to two cards, and the player who took the third last card discards without knocking. In this case the hand is cancelled, there is no score, and the same dealer deals again. Some play that after the player who took the third last stock card discards, the other player can take this discard for the purpose of going gin or knocking after discarding a different card, but if the other player does neither of these the hand is cancelled.

Scoring Each player counts the total value of their unmatched cards. If the knocker's count is lower, the knocker scores the difference between the two counts.

If the knocker did not go gin, and the counts are equal, or the knocker's count is greater than that of the opponent, the knocker has been undercut. In this case the knocker's opponent scores the difference between the counts plus a 10 point bonus.

A player who goes gin scores a bonus 20 points, plus the opponent's count in unmatched cards, if any. A player who goes gin can never be undercut. Even if the other player has no unmatched cards at all, the person going gin gets the 20 point bonus the other player scores nothing.

The game continues with further deals until one player's cumulative score reaches 100 points or more. This player then receives an additional bonus of 100 points. If the loser failed to score anything at all during the game, then the winner's bonus is 200 points rather than 100.

In addition, each player adds a further 20 points for each hand they won. This is called the line bonus or box bonus. These additional points cannot be counted as part of the 100 needed to win the game.

After the bonuses have been added, the player with the lower score pays the player with the higher score an amount proportional to the difference between their scores.

Variations Many books give the rule that the winner of each hand deals the next. Some play that the turn to deal alternates.

Some players begin the game differently: the non-dealer receives 11 cards and the dealer 10, and no card is turned up. The non-dealer's first turn is simply to discard a card, after which the dealer takes a normal turn, drawing the discard or from the stock, and play alternates as usual.

Although the traditional rules prohibit a player from taking the previous player's discard and discarding the same card, it is hard to think of a situation where it would be advantageous to do this if it were allowed. The Gin Rummy Association Rules do explicitly allow this play, but the player who originally discarded the card is then not allowed to retake it unless knocking on that turn. The Game Colony Rules allow it in one specific situation - "action on the 50th card". When a player takes the third last card of the stock and discards without knocking, leaving two cards in the stock, the other player has one final chance to take the discard and knock. In this position, this same card can be discarded - if it does not improve his hand, the player simply turns it over on the pile to knock.

Some people play that the bonus for going gin is 25 (rather than 20) and the bonus for an undercut is 20 (rather than 10). Some play that the bonus for an undercut, the bonus for going gin, and the box bonus for each game won are all 25 points.

Some play that if the loser failed to score during the whole game, the winner's entire score is doubled (rather than just doubling the 100 game bonus to 200).

A collection of variations submitted by readers can be found on the Gin Rummy Variations page.

Oklahoma Gin In this popular variation the value of the original face up card determines the maximum count of unmatched cards with which it is possible to knock. Pictures denote 10 as usual. So if a seven is turned up, in order to knock you must reduce your count to 7 or fewer.

If the original face up card is a spade, the final score for that deal (including any undercut or gin bonus) is doubled.

The target score for winning Oklahoma Gin is generally set at 150 rather than 100.

Some play that if an ace is turned up you may only knock if you can go gin.

Some play that a player who undercuts the knocker scores an extra box in addition to the undercut bonus. Also a player who goes gin scores two extra boxes. These extra boxes are recorded on the scorepad; they do not count towards winning the game, but at the end of the game they translate into 20 or 25 points each, along with the normal boxes for hands won. If the up-card was a spade, you get two extra boxes for an undercut and four extra boxes for going gin.

Playing with 3 or 4 Players. When three people play gin rummy, the dealer deals to the other two players but does not take part in the play. The loser of each hand deals the next, which is therefore played between the winner and the dealer of the previous hand.

Four people can play as two partnerships. In this case, each player in a team plays a separate game with one of the opposing pair. Players alternate opponents, but stay in the same teams. At the end of each hand, if both players on a team won, the team scores the total of their points. If one player from each team won, the team with the higher score scores the difference. The first team whose cumulative score reaches 125 points or more wins.

Other Gin Rummy pages The Gin Rummy Association's Gin Rummy Tournaments page has information about forthcoming Gin Rummy events, including regular live tournaments in Las Vegas, and the site includes a summary of the rules used in these tournaments.

The Gin Rummy pages of Rummy-Games.com give rules for many Gin Rummy variants, plus reviews of Gin Rummy software and online games.

Several variants of Gin Rummy are described on Howard Fosdick's page (archive copy).

Gin Rummy rules are also available on the Card Games Heaven web site.

A comprehensive set of rules for Gin Rummy in German can be found on Roland Scheicher's Gin Rummy page.

Rummy.ch is a German language site offering rules for Gin Rummy and many other rummy games, plus strategy articles and reviews of online rummy sites and a forum.

Software and Servers Gin Rummy software: Malcolm Bain's classic Gin Rummy program for Windows is available from Card Games Galore. A shareware Gin Rummy program can be downloaded from Meggiesoft Games. A free trial version is available. The collection HOYLE Card Games for Windows or Mac OS X includes a Gin Rummy program, along with many other popular card games. The Gin Rummy Pro computer program is available from Recreasoft. Special K Software has software to play the game of Gin Rummy. This software is available at www.specialksoftware.com. Best Gin Rummy by KuralSoft is a program for iOS with which you can play Gin Rummy against a computer opponent. Games4All has published a free Gin Rummy app for the Android platform. Blyts have published Gin Rummy Free in versions for iOS, Android and web browser. Servers for playing Gin Rummy on-line: Gin Rummy League is a free iPhone/iPad app for online Gin Rummy. Game Colony offers head to head Gin Rummy games and multi-player tournaments, which can be played free or for cash prizes. Net Gin Rummy, which allows you to play against a computer opponent or with a human opponent over the Internet, LAN, modem or direct connection, is available from NetIntellGames. Mystic Island AOL games (formerly games.com / Masque publishing) offers Gin Rummy and Oklahoma Gin Gaming Safari Ludopoli (Italian language) PlayOK Online Games (formerly known as Kurnik) World of Card Games Cardzmania Yimmaw Gameslush.com offers an online Gin Rummy game against live opponents or computer players. Rubl.com Cowboy Gin Rummy is an idiosycratic version of Gin played online against the computer, in which the object is to win as many hands in succession as possible in the minimum time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skat card game

#SKAT CARD GAME PLUS#

Then follow the remaining seven cards of the chosen suit, making eleven trumps in all, ranking from highest to lowest: Irrespective of the suit chosen as trumps, the four jacks are the top four trumps, ranking in the fixed order. The ranking of the cards depends on the game the declarer chooses to play. In this article French suits are assumed, but in case you are using German suited cards the correspondence is as follows: 32 cards are used: A K Q J 10 9 8 7 in each suit. Elsewhere, Skat is played with French suited cards. Skat was originally played with German suited cards, and these are still in general use in South and East Germany, including Altenburg. In is important to realise that in Skat the card points, which generally determine whether the declarer wins or loses, are quite separate from the game points, which determine how much is won or lost. Declarer generally wins the value of the game if successful, and loses the twice the game value The value of the game, in game points, depends on the trumps chosen, the location of the top trumps ( matadors) and whether the declarer used the skat. Instead of naming a trump suit the declarer can choose to play Grand (jacks are the only trumps) or Null (no trumps and the declarer's object is to lose all the tricks).

#SKAT CARD GAME PLUS#

To win, the declarer has to take at least 61 card points in tricks plus skat the opponents win if their combined tricks contain at least 60 card points. Some cards have point values, and the total number of card points in the pack is 120. The declarer has the right to use the two skat cards to make a better hand, and to choose the trump suit. The winner of the bidding becomes the declarer, and plays alone against the other two players in partnership. Each active player is dealt 10 cards and the remaining two form the skat. It is also quite often played by four people, but there are still only 3 active players in each hand the dealer sits out. Skat is a three-handed trick taking game. In parts of the USA other versions of Skat survive: Texas Skat is fairly close to the German game but in Wisconsin they play a significantly different game: Tournée Skat, which was brought by immigrants from Germany in the 19th century and reflects the form of Skat which was played in Germany at that time. In Skat clubs in Germany, the game is generally played as described here, though often with tournament scoring. In social games many variations will be encountered. The main description on this page is based on the current version of the official German and International rules (which were revised on 1st January 1999). Note: Skat is not to be confused with the American game Scat - a simple draw and discard game in which players try to collect 31 points in a three card hand. Altenburg is still considered the home of Skat and has a fountain dedicated to the game. They adapted the existing local game Schafkopf by adding features of the then popular games Tarok and l'Hombre. It was invented around 1810 in the town of Altenburg, about 40km south of Leipzig, Germany, by the members of the Brommesche Tarok-Gesellschaft. Skat is the national card game of Germany, and one of the best card games for 3 players.

Other sites for Skat information and discussion.

Tournament Scoring - Kontra and Rekontra - Ramsch - Bockrounds and Ramschrounds - Schenken - Spitze - Scoring and Contract variations - Open Contracts - Rum - Playing with a Pot Please send e-mail to Mike Tobias at if you are interested in hearing about future events. Association, founded by David Parlett, holds regular tournaments in the UK.

0 notes