#Izvestiya

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

HAVANA TIMES / TASS: Russia - Cuba / Russland - Kuba

HAVANA TIMES / TASS: Russia – Cuba / Russland – Kuba Russia’s UAZ Opens a Vehicle Assembly Plant in Cuba / Russlands UAZ eröffnet ein Fahrzeugmontagewerk in Kuba The company was founded in 1941 to provide the USSR with vehicles to face the advance of German troops. (TASS/Izvestiya) Das Unternehmen wurde 1941 gegründet, um die UdSSR mit Fahrzeugen auszustatten, mit denen sie dem Vormarsch…

View On WordPress

#«Авиакомпания „Россия“#Варадеро#Ульяновск#Ульяновский автомобильный завод#Havana Times#Izvestiya#La Havana#Moscú#Rossiya Airlines#TASS#UAZ#Uliánovsk#Uliánovski Avtomobilny Zavod#Unión Soviética#Varadero

0 notes

Text

A group of policemen in body armour and helmets burst into a mosque during prayer, released tear gas and shoved men, women and children to the ground. This event in the Moscow suburb of Kotelniki in July was widely reported in the Russian press. The disturbing footage was first shared on a popular xenophobic Telegram channel.

It was one of dozens of raids targeting migrant workers in Russia this year. A large-scale campaign against illegal migrants known as ‘Nelegal-2023’ was carried out by law enforcement in two stages in June and October. Russia’s Interior Ministry told the newspaper Izvestiya last month that over 15,000 migrants have been deported from the country in the course of the campaign.

With the help of our interns, Bellingcat collected and analysed imagery of these raids and detentions shared on social media channels. We found 60 videos and photos depicting 50 raids between May and August, the chief period of focus of our research. This was a particularly active period which included the first stage of Nelegal-2023. We found 29 videos filmed during this time, 27 of which we were able to geolocate.

We also discovered extensive footage of subsequent events during and after the second stage of Nelegal-2023 in autumn, though this period was not monitored as closely by our researchers. Overall we found 14 videos which depict law enforcement committing violence against migrants between May and November, 13 of which could be geolocated. This is far from an exhaustive survey of the available open source evidence.

A key source of footage of these raids was a series of xenophobic Telegram channels, such as Многонационал (‘Multinational’), Русская Община (‘Russian Community’). The same footage also surfaced on other xenophobic channels including Северный Человек (‘Northern Man’) and smaller far-right groups. Bellingcat has chosen not to link to these channels to avoid amplification.

As their names suggest, these channels have strongly nationalist positions and have shared videos of police detentions of migrants since at least 2019. Similar examples could occasionally be found on smaller local interest Telegram channels focused on particular districts of large cities.

We also found indications that members of these channels don’t just comment approvingly on police raids against labour migrants in Russia – they are actively involved in instigating these raids. They regularly publicise events or the addresses of places where migrants – or those they perceive to be migrants – gather with a view to alerting law enforcement. When police raids follow, members of these xenophobic groups are on the scene with their smartphones to record detentions of migrants, which they share with their hundreds of thousands of approving followers. Russia’s Ministry of the Interior did not respond to Bellingcat’s requests for comment.

Far-right anti-migration activism has risen drastically since the start of 2023, states Vera Alperovich, an expert with the Moscow-based SOVA Centre, an NGO which monitors nationalism and racism in Russia. “No longer limiting themselves to the role of the critical observer, nationalists have started to create newsworthy events themselves, joining a battle in the name of local residents”, she wrote in a monitoring report for SOVA Centre in June.

Gyms, Mosques and Cafes

Apart from the aforementioned case of the raid on the mosque in Kotelniki, several other videos of detentions of migrants have surfaced on social media since the first stage of Nelegal-2023 began. Most of the raids analysed by Bellingcat took place in Moscow or cities in the surrounding Moscow Region. Still, there were also a few cases in Krasnodar, Samara, St Petersburg, Yekaterinburg and the Siberian cities of Chelyabinsk, Blagoveshchensk and Irkutsk. These raids have taken place at migrants’ places of work, such as construction sites and markets; their places of residence, such as apartments, hostels and dormitories; and , places for public gatherings, including a Central Asian cafe, gyms, and a football field. In several cases, the far-right Telegram channels appear to have played a role in inciting the raids. One such incident on May 28 was recorded extensively from the football field at School No.811 in Moscow’s Mozhaysky District (55.711889 37.400803). That morning, the ‘Russian Community’ Telegram channel shared a video compilation which began with schoolchildren complaining that a group of migrants had forced them off the playground and verbally abused them and their parents. In the same clip the men can later be seen playing football, as a woman can be heard complaining to the camera.

The clip includes close-up footage of men being led away by police, who lay some of the men on the ground and beat them with truncheons. It ends with representatives of the movement on the same football field talking about the successful operation and urging Russians to contact them if they encounter similar problems.

According to the text of the Telegram post, the parents had complained directly to ‘Russian Community’, which filed a complaint with the police with legal assistance. “While our guys on the front are beating the enemy, on the home front, the Russian Community is defending our families” it declares. A few hours later, the channel posted again to claim that 49 migrants had been detained during the event.

These arrests were celebrated by other xenophobic Telegram channels such as ‘Multinational’, which shared two of the same clips of police violence against the migrants at the football field it said was now “free from foreign occupiers”.

A further video shared by the Tajik YouTube channel Bomdod TV on June 1 shows a group of men sitting beside outdoor exercise equipment near the football field as police beat and kick them. The impact of the kicks is audible even though the cameraperson is filming from behind a fence several metres away from the scene.

A survey of the Telegram channel shows that this wasn’t the first time the ‘Russian Community’ had confronted migrants on football fields in Moscow, usually by sending members to ‘have chats’. However, it appears to be the first in which they successfully called on the authorities to help. Two months later, the channel decried ‘persecution’ of the police officers involved after revealing that a complaint had been filed against them.

On July 31, the ‘Russian Community’ turned its attention to two ‘migrant boxing clubs’ in Moscow. In a video shared on its Telegram channel, migrants are made to lie on the floor of the gym with their hands behind their necks. Several of them wear only underwear. They are made to do squat jumps in a line on the tarmac outside. The cameraperson accompanied police on the raid. However, the cameraperson can’t be seen in the video and at no point do they appear in a reflection or move in view of the lens, making it impossible to determine whether they were a civilian or a member of law enforcement.

In contrast to the incident on the football field, ‘Russian Community’ did not claim that any locals had complained about the migrants, simply asserting without evidence that such martial arts clubs attracted ‘criminal elements’. However, this concern about martial arts is only apparent when migrants or those perceived to be migrants are involved. One of the two gyms, in Moscow’s Tagansky District (55.738105,37.666178), is located in the same building as a knife fighting club with a Russian Imperial military coat of arms and the name ‘Patriot’. It did not attract the same scrutiny from the Telegram community.

The same post claimed without evidence that a half and a third of those whose documents were checked by police at the two gyms had violated migration law.

Open source information indicates that riot police raided at least a dozen Central Asian restaurants over June, July and August – during and in the months immediately after the first phase of Nelegal-2023. Most of them were in Kotelniki, 22 kilometres from Moscow. On July 13 the ‘Russian Community’ Telegram channel wrote of raids on four restaurants leading to the detention of 30 people, “one in five of whom was illegal!” A video shows the police forcing the clientele and staff of the Didor Restaurant (55.66047160167306, 37.85544956623931) onto the ground, some of whom they then beat and kick. Didor is a Central Asian restaurant; traditional flat bread can be seen on the tables and the word ‘Didor’ derives from a greeting in Tajik.

Once again, as in the case of the prayer room in the same town and the football field in Moscow, the ‘Russian Community’ claims that the raid took place after complaints by locals. Once again, the cameraman accompanies the police during the raid though they cannot be identified. These clips and others showing the same events were also shared by ‘Multinational’.

Raids also took place at construction sites. On May 21 a post appeared in the ‘Right View’ Telegram channel containing two videos showing what it said were police detentions of migrants in Kotelniki – one showed men fleeing a cafe during a raid, the other an altercation between migrant construction workers and police. This channel is explicitly far-right and proclaims its support for a ‘White Europe’.

The second of these two videos appeared later that day in the Overheard in the Police and National Guard Telegram channel. Geolocation reveals that this second scene in fact took place outside the Lakhta Centre in St Petersburg’s Primorsky District (59.988985, 30.174993).

Two police officers are seen kicking and beating a man as his fellow workers in hard hats and high-visibility jackets stand and watch. They may be construction workers at the nearby Lakhta Centre 2, which will become the tallest skyscraper in Russia upon completion. Soon afterwards the policemen shove him onto a bus packed with other workers as they check passports. The migrant is heard saying that he did not have his documents with him as he had stepped out for lunch, to which a person in civilian clothes replies, “have your lunch at work, not here”.

Two weeks later, the cameraman in a video posted by ‘Multinational’ walks around the same area and complains about a street market where dozens of construction workers are seen buying food. The post garnered over 100,000 views. The very next day, the same channel posted that riot police had raided the area and detained several migrants – a claim backed up in two videos showing the same street. In July, the channel complained about the same area. Raids in September followed; a police officer kicked over boxes of bread, which construction workers scurried to pick up off the ground.

On October 30, Russian police raided an Azerbaijani wedding in the Kurakina Dacha restaurant in St Petersburg and, according to Azerbaijani media, detained five men. CCTV footage from the event uploaded to Telegram shows police beating two of the guests.

More recently, on November 15, police burst into a birthday party at the Fort restaurant in the city of Voronezh and detained a number of Azerbaijani men who were reportedly then requested to attend the military recruitment office. The ‘Multinational’ Telegram channel celebrated both incidents — the post below notes that ‘we need to pay more attention to weddings and birthday parties’. It is not clear whether the channel helped organise the raids. However, there is no evidence that ‘Multinational’ has shown the same scrutiny towards mass events or celebrations by ethnic Russians.

Most of these incidents show some level of coordination between Russian law enforcement and several xenophobic, nationalist online communities that frequently claim to be addressing the concerns of local Russian residents. Bellingcat used reverse image searching of screenshots of these videos and specific keyword searches to establish the origin of these videos. In most cases, we were unable to find these particular pieces of footage shared online earlier than when the aforementioned Telegram channels first posted them. Bellingcat was also unable to find clear statements from police that they support or monitor these channels. However, the correlation between the xenophobic channels’ reports on ‘migrant activity’ followed by rapid police raids suggests that one exists. Detentions of migrant workers continue to take place at a large scale across Russia; these channels continue to post about them supportively.

‘Raids at the Request of the Russian Community’

In the first stage of Nelegal-2023 alone, Bellingcat found five instances where police raids immediately followed xenophobic channels posting the location of ‘migrants’. A large proportion of the videos showing Russian police detentions of migrants were taken from Russian nationalist Telegram channels. The two largest were ‘Russian Community’ and ‘Multinational’, which have 150,000 and 206,000 subscribers respectively. They also openly boast of their ‘coordination with law enforcement’, such as in a July 4 post by the former thanking the police for raids ‘at the request of the Russian community’.

Some closed nationalist Telegram channels also reportedly inform police about gatherings of labour migrants. According to Al Jazeera, the closed group ZOV is one of them and is run by a former staffer at Tsargrad TV, a nationalist media network funded by oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev. The group’s name translates as ‘call’ and refers to three Latin letters that have become symbols of the invasion of Ukraine.

A look at the posts on ‘Russian Community’ and ‘Multinational’ both before the start of Nelegal-2023 and at the time of writing shows that their members are staunch supporters of Russia’s war against Ukraine. For example, they collect donations for the military. ‘Russian Community’s main channel includes the phrase ZOV in its title; the group also runs a channel for occupied Mariupol in Ukraine.

Andrey Tkachuk, the coordinator of Russian Community, set out his vision for Russian migration policy in a video in July. He demanded the institution of a visa regime with Central Asian and South Caucasus states, an end to ‘easy’ acquisition of Russian citizenship after permanent residency and spoke against the existence of informal community organisations for migrants. Tkachuk, who stated that his was not a fascist or far-right movement, said in the same video that ‘there is no such thing as Ukraine’.

Bellingcat found several posts from these groups criticising even small attempts by Russian officials to improve relations with migrant communities.

These groups have also developed conspiracy theories to justify their xenophobia. In an April 23 post on ‘Russian Community’s Telegram account, the movement blamed ‘western security services’ for trying to create a ‘new proletariat’ in Russia to act in their interests: ‘millions of migrants, called by somebody to Russia’. This portrayal of migrants as a ‘fifth column’ can be found in older posts on these Telegram channels.

It is clear from these channels’ posts that they attempt to direct police towards areas where ‘migrants’ congregate – including, as shown above, areas which may be frequented by Russian citizens with origins in Central Asia or the Caucasus, such as mosques and certain restaurants.

For example, on June 21 the Russian Community Telegram channel stated that they were responsible for enforcement discovering two apartments full of ‘migrants’. When some migrants resisted arrest, ‘our guys’ fought them off, claims the channel. However, it is not clear whether ‘our guys’ refers to the police or members of the channel.

And the police appear to be watching. As mentioned earlier, the majority of videos of police raids against migrants occurred in the Moscow suburb of Kotelniki. Here, a Russian Community Telegram post from June 14 claims that ‘according to local activists, the chat is regularly monitored by representatives of the Kotelniki district police’.

The ‘Russian Community’ have also claimed to carry out their own ‘raids’. In some cases they have tried to incite police raids in person, not merely by posting addresses online. One such example can be seen outside the central market of Novosibirsk (55.042847, 82.923846), which was uploaded to the group’s Telegram channel on June 23.

A group of men surround a fruit seller on the street and demand that he show them his documents to prove that he is there legally on the grounds that they are customers. His requests to not be filmed are ignored. They ask him who gave him permission to be there, then accuse him of evading taxes and selling food without a licence.

The leader of the group then takes out his telephone and calls the police on the scene, telling them to come to the spot where he has registered a ‘case of illegal trading’. The accompanying post states that the police did not arrive on the scene at Russian Community’s request – which they cite as evidence that the ‘illegal traders’ have some kind of protection.

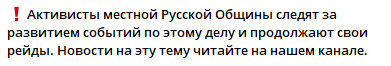

The same post containing the video ends with a statement that Russian Community continues to monitor the situation and to carry out ‘our own raids’:

These communities also appear to eager to see their members within the ranks of law enforcement. On September 3, ‘Multinational’ posted a link to two job vacancies in a Moscow police department, promoting it as an opportunity ‘to fight against criminality, including ethnic criminality, and to take part in raids’.

Bellingcat was also unable to find any statements from Russia’s police or Ministry of the Interior about these channels nor whether their employees monitor them. Russia’s Ministry of the Interior, which is responsible for law enforcement, did not respond to Bellingcat’s requests for comment about whether police used information from the aforementioned Telegram channels or allowed their members to accompany police on raids. ‘Russian Community’ did not respond to Bellingcat’s request for comment. However, an administrator of the ‘Multinational’ Telegram channel called us ‘enemies of Russia’ and said that he refused answer our questions, only to then answer two of them. “We carry out our activities independently from any state structures and there are no employees of any law enforcement agencies among our leadership”, he answered in a Telegram message.

Old Trends, New Alliances

This wave of arrests is far from the first in Russia, which has a history of violent police arrests of labour migrants. However, speculation about the motivation for recent raids abounds, given that they occur against the backdrop of Russia’s war on Ukraine. The Russian journalist Andrei Soldatov writes that ongoing arrests may be a further attempt by the Russian military to replenish its depleted ranks without resorting to a general mobilisation. New decrees in 2022 permit foreign citizens to sign contracts to serve in the Russian military.

In the case of some channels, the motivation to send ‘migrants’ to fight in Ukraine is more explicit. Below, a flyer circulated by the ‘Northern Man’ Telegram channel repurposes ‘The Motherland Calls’, a famous Soviet propaganda poster from 1941. The poster reads ‘If your neighbour is a migrant, call the military recruitment office!’ Although the text of the Telegram post announces an ‘initiative of the residents of the Moscow region to help the military enlistment office search for illegal migrants‘, the text on the scroll in the poster urges supporters to look for ‘newly-minted citizens of the Russian Federation… who have forgotten to sign up’.

However, Valentina Chupik, an activist and lawyer from Uzbekistan whose NGO defends the rights of labour migrants in Russia, told Bellingcat in an interview that she did not believe conscription was the primary goal for the latest wave of police raids on labour migrants — whatever may motivate such xenophobic channels.

Most labour migrants from Central Asia, she explained, are not Russian citizens. Those men detained during police raids who then receive military summons may be Russian citizens of Central Asian descent or domestic migrants from majority-Muslim areas of Russia, said Chupik. The xenophobic channels’ assumption that those present at Central Asian restaurants or mosques must be ‘illegal immigrants’ suggests that anti-migrant activists do not distinguish between these two groups, she continued.

“What makes this year different is the lower number of migrants in Russia, more violence, and more coordination with the Nazis”, she said. Based on the number of migrants who have appealed to her colleagues for assistance, Chupik says that she knows of around 18,000 detentions of migrants in Russia this year so far — a scale, she says, much lower than the average of 25,000 detentions in the early to mid-2010s. This she attributes in part to the lower number of labour migrants in Russia following the Covid-19 pandemic and the economic disruption following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Yes, there’s coordination”, Chupik remarked. “But the leading role here isn’t played by the Nazi organisations. The police use them to track those places where migrants can be found. The police are lazy; the Nazis are the dependent side here… They are prepared to work with these people for as long as it profits them”, she concluded.

The activities of groups like the ‘Russian Community’ are a good example of the Russian far-right’s adaptation to new political realities, wrote Alperovich, the SOVA Centre expert, in the same report from June. “They position themselves as social, not political movements and declare that they are not interested in fighting for power. They defend conservative morals and Orthodox values but most of their activity is directed at the fight against migrants”.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Impact of Solidarity in Poland on Eastern Europe

The Solidarity Union in Poland, formed in the autumn of 1980, became a significant source of inspiration for human rights movements throughout Eastern Europe. Its success led workers in other countries to follow suit. In Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics, workers began to strike, pushing for more rights and better conditions. Even in Bulgaria, voices of discontent grew stronger, and subversive ideas began to emerge.

The Bulgarian Secret Service Response

In September 1980, the Bulgarian Secret Service (Directorate Six), tasked with monitoring political enemies, was assigned to prevent any organized anti-socialist activities linked to the Solidarity movement in Poland. Their job was to stop any influence from the Polish unions and counter-revolutionary ideas from spreading into Bulgaria. Directorate Six focused on the intelligentsia, young people, and anyone suspected of being opposed to the government Customized Tour Istanbul.

By the end of 1980, Directorate Six conducted operations targeting intellectuals, students, and those who were seen as a threat to the regime. They attempted to stop any movement that could lead to unrest, particularly from the Polish influence. This led to the imposition of strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and all types of Polish propaganda materials that were seen as promoting ideas contrary to the communist system.

Concerns Over Polish Influence

In the summer of 1980, many Polish tourists visited Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, which raised concerns within the State Security. The authorities were worried that these tourists could spread pro-democracy ideas and encourage the Bulgarian people to challenge the regime.

To counteract this, the Bulgarian press began to publish propaganda that misrepresented the situation in Poland. The goal was to create a false image of the Polish trade unions, portraying them as being influenced by Western powers. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, published numerous articles from the Soviet newspapers Pravda and Izvestiya, which attacked the Solidarity movement and its supporters. These articles aimed to show that Poland’s internal problems were caused by foreign interference.

Growing Discontent in Bulgaria

On 14 October 1981, Todor Zhivkov, the leader of Bulgaria, submitted a memorandum to the Politburo expressing his concern that the Polish movement might inspire similar protests in Bulgaria. The State Security continued to monitor the growing discontent, especially among young people. Directorate Six noticed an increase in anonymous leaflets and small gatherings in private homes where people discussed the situation in Poland.

In particular, a group of young people in Bulgaria began to work on a “Declaration-80”, a document that expressed support for the Polish struggle for democracy. The authorities saw this as a threat to the regime and quickly classified it as a “menace to the rule of law”.

The Solidarity Union in Poland sparked a wave of protests and uprisings across Eastern Europe, and Bulgaria was not immune to this growing demand for change. However, the Bulgarian government, led by Todor Zhivkov, responded with intense repression, including strict censorship and surveillance of its citizens. Despite these efforts, the spirit of democratization that emerged in Poland began to inspire more people in Bulgaria, particularly the younger generation, who increasingly questioned the totalitarian regime under which they lived.

0 notes

Photo

The Impact of Solidarity in Poland on Eastern Europe

The Solidarity Union in Poland, formed in the autumn of 1980, became a significant source of inspiration for human rights movements throughout Eastern Europe. Its success led workers in other countries to follow suit. In Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics, workers began to strike, pushing for more rights and better conditions. Even in Bulgaria, voices of discontent grew stronger, and subversive ideas began to emerge.

The Bulgarian Secret Service Response

In September 1980, the Bulgarian Secret Service (Directorate Six), tasked with monitoring political enemies, was assigned to prevent any organized anti-socialist activities linked to the Solidarity movement in Poland. Their job was to stop any influence from the Polish unions and counter-revolutionary ideas from spreading into Bulgaria. Directorate Six focused on the intelligentsia, young people, and anyone suspected of being opposed to the government Customized Tour Istanbul.

By the end of 1980, Directorate Six conducted operations targeting intellectuals, students, and those who were seen as a threat to the regime. They attempted to stop any movement that could lead to unrest, particularly from the Polish influence. This led to the imposition of strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and all types of Polish propaganda materials that were seen as promoting ideas contrary to the communist system.

Concerns Over Polish Influence

In the summer of 1980, many Polish tourists visited Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, which raised concerns within the State Security. The authorities were worried that these tourists could spread pro-democracy ideas and encourage the Bulgarian people to challenge the regime.

To counteract this, the Bulgarian press began to publish propaganda that misrepresented the situation in Poland. The goal was to create a false image of the Polish trade unions, portraying them as being influenced by Western powers. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, published numerous articles from the Soviet newspapers Pravda and Izvestiya, which attacked the Solidarity movement and its supporters. These articles aimed to show that Poland’s internal problems were caused by foreign interference.

Growing Discontent in Bulgaria

On 14 October 1981, Todor Zhivkov, the leader of Bulgaria, submitted a memorandum to the Politburo expressing his concern that the Polish movement might inspire similar protests in Bulgaria. The State Security continued to monitor the growing discontent, especially among young people. Directorate Six noticed an increase in anonymous leaflets and small gatherings in private homes where people discussed the situation in Poland.

In particular, a group of young people in Bulgaria began to work on a “Declaration-80”, a document that expressed support for the Polish struggle for democracy. The authorities saw this as a threat to the regime and quickly classified it as a “menace to the rule of law”.

The Solidarity Union in Poland sparked a wave of protests and uprisings across Eastern Europe, and Bulgaria was not immune to this growing demand for change. However, the Bulgarian government, led by Todor Zhivkov, responded with intense repression, including strict censorship and surveillance of its citizens. Despite these efforts, the spirit of democratization that emerged in Poland began to inspire more people in Bulgaria, particularly the younger generation, who increasingly questioned the totalitarian regime under which they lived.

0 notes

Photo

The Impact of Solidarity in Poland on Eastern Europe

The Solidarity Union in Poland, formed in the autumn of 1980, became a significant source of inspiration for human rights movements throughout Eastern Europe. Its success led workers in other countries to follow suit. In Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics, workers began to strike, pushing for more rights and better conditions. Even in Bulgaria, voices of discontent grew stronger, and subversive ideas began to emerge.

The Bulgarian Secret Service Response

In September 1980, the Bulgarian Secret Service (Directorate Six), tasked with monitoring political enemies, was assigned to prevent any organized anti-socialist activities linked to the Solidarity movement in Poland. Their job was to stop any influence from the Polish unions and counter-revolutionary ideas from spreading into Bulgaria. Directorate Six focused on the intelligentsia, young people, and anyone suspected of being opposed to the government Customized Tour Istanbul.

By the end of 1980, Directorate Six conducted operations targeting intellectuals, students, and those who were seen as a threat to the regime. They attempted to stop any movement that could lead to unrest, particularly from the Polish influence. This led to the imposition of strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and all types of Polish propaganda materials that were seen as promoting ideas contrary to the communist system.

Concerns Over Polish Influence

In the summer of 1980, many Polish tourists visited Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, which raised concerns within the State Security. The authorities were worried that these tourists could spread pro-democracy ideas and encourage the Bulgarian people to challenge the regime.

To counteract this, the Bulgarian press began to publish propaganda that misrepresented the situation in Poland. The goal was to create a false image of the Polish trade unions, portraying them as being influenced by Western powers. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, published numerous articles from the Soviet newspapers Pravda and Izvestiya, which attacked the Solidarity movement and its supporters. These articles aimed to show that Poland’s internal problems were caused by foreign interference.

Growing Discontent in Bulgaria

On 14 October 1981, Todor Zhivkov, the leader of Bulgaria, submitted a memorandum to the Politburo expressing his concern that the Polish movement might inspire similar protests in Bulgaria. The State Security continued to monitor the growing discontent, especially among young people. Directorate Six noticed an increase in anonymous leaflets and small gatherings in private homes where people discussed the situation in Poland.

In particular, a group of young people in Bulgaria began to work on a “Declaration-80”, a document that expressed support for the Polish struggle for democracy. The authorities saw this as a threat to the regime and quickly classified it as a “menace to the rule of law”.

The Solidarity Union in Poland sparked a wave of protests and uprisings across Eastern Europe, and Bulgaria was not immune to this growing demand for change. However, the Bulgarian government, led by Todor Zhivkov, responded with intense repression, including strict censorship and surveillance of its citizens. Despite these efforts, the spirit of democratization that emerged in Poland began to inspire more people in Bulgaria, particularly the younger generation, who increasingly questioned the totalitarian regime under which they lived.

0 notes

Text

just wanted to add that the video footage does not show the breach of the dam itself. it is from nov 2022 when russian forces destroyed the road and rail bridge:

apparently the dam itself remained structurally intact at the time.

but yes, like op said, russia was already suspected of planning a false flag attack on the dam in october 2022 when it was confirmed that they had mined the dam:

Yes, they have done it, the act of ecocide. It was predicted almost a year ago when it was first reported that the Russians had mined the dam. They've been preparing for it. Over the past few months, they have been draining the reservoir while simultaneously filling all reservoirs in Crimea, because blowing up this dam means no more fresh water supply to Crimea. So everyone who claimed that Russia invaded Ukraine to secure fresh water for Crimea can now go fuck themselves.

Of course they first claimed it was Ukraine's doing. Although some occupiers already happily admit that it was russia who blew it up, and call for blowing up more of Ukraine's infrastructure.

UPDATE: video evidence that the russians did in fact blew it up, and it wasn't destroyed due to any shelling from the Ukrainian side

It's typical russian scorched earth tactics. Blowing up the dam can possibly prevent the Ukrainian army landing on the left bank of the Dnipro, and it frees russian troops from the left bank, meaning they can be sent as reinforcement to other front lines, for example, in the Donetsk region.

It is probably the greatest ecological catastrophe since Chornobyl, with thousands of people affected, left homeless, entire villages destroyed probably forever. But the russians don't give two fucks about that. They don't care about any life. Their main objective is not necessarily to claim the land for themselves, but rather to ensure it is not Ukrainian. If they cannot have it, they want to leave it uninhabitable.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Georgian president said there was no evidence of Russian interference in the election

Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili told Reuters she had no evidence of any Russian interference in the last parliamentary elections, but considered the links between the country's ruling party and Moscow ‘obvious’.

‘We don't have precise evidence, but the obvious ties that the ruling party has with Moscow have been confirmed by numerous reports,’ she said in an interview, a recording of which was published on 28th October on the agency's YouTube channel.

Zourabichvili expressed the opinion that she should not provide any evidence of vote rigging. According to the Georgian president, there was enough information from local observers in this regard, while international observers do not always react to violations in time.

She added that if the newly convened Georgian parliament decides to hold a session regardless of her disagreement with the election results, the country's citizens will come out in protests on the same day.

Zourabichvili also suggested that opposition parties may demand an investigation into reports of irregularities and a new round of voting with the support of Tbilisi's European partners.

Voting in Georgia's parliamentary elections took place on 26th October. According to the CEC, the ruling Georgian Dream party won with more than 50 per cent of the vote. Three opposition parties - United National Movement, Coalition for Change and Strong Georgia - did not recognise the election results. One of the leaders of the Coalition, Elene Khoshtaria, announced the start of protests from 27th October.

Zourabichvili expressed her disagreement with the election results at the same time, calling the results a total fraud. As Izvestiya's correspondent reported, several people with Ukrainian and European flags marched to the Georgian parliament building at the same time.

On 28th October, Kremlin spokesman Dmitriy Peskov described the Georgian election as an internal affair of the country in which the Russian side does not interfere. He pointed out that the Russian Federation strongly rejects any unsubstantiated accusations in this regard, which are already standard for many countries.

Source: iz.ru

Picture: illustrative

Video: iz.ru

#news#russia#georgia#voting#salome zourabichvili#dmitriy peskov#kremlin#russian federation#khoshtaria#eu#europe

0 notes

Photo

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The signing of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975 brought hope to the nations of the Eastern bloc. This document reaffirmed human rights as a fundamental principle, inspiring people living under totalitarian regimes to seek freedom and justice. It became a powerful tool for those wanting to challenge their governments.

Rise of New Opposition

With the Final Act as a backdrop, a new type of opposition began to emerge across Eastern Europe. More citizens started to openly protest against the restrictions on their rights, demanding that these rights be respected by the communist authorities. The activities of the Solidarity Union in Poland became particularly influential, energizing human rights movements throughout the region.

In the autumn of 1980, inspired by the Polish workers’ struggle for their rights, workers in Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics also began to strike. In Bulgaria, discontent started to surface as well. The government recognized the growing unrest, leading Directorate Six of the Secret Service, which monitored political enemies, to take action. Their task was to prevent any organized opposition that might be influenced by the anti-socialist forces in Poland Rose Festival Tour.

Government Response

By the end of 1980, the Directorate was conducting targeted operations aimed at the intelligentsia, youth, and perceived counter-revolutionaries. The authorities imposed strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and any propaganda materials coming from Poland. This censorship aimed to control the narrative and prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas.

The influx of Polish tourists to Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast during the summer raised alarms for the State Security. The government worried that these visitors might share ideas of dissent with local citizens, further stirring unrest.

Propaganda and Misinformation

To combat the growing influence of Polish movements, the Bulgarian press became a tool for propaganda. The media published distorted accounts of the situation in Poland to mislead the public about the goals of Polish trade unions and the desire of Polish people for democracy. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, frequently reprinted articles from Soviet publications like Pravda and Izvestiya. These articles claimed that Western powers were interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, painting a picture of external threats to justify the regime’s actions.

In conclusion, the signing of the Final Act in 1975 catalyzed a wave of hope and resistance in Eastern Europe. The emergence of new opposition movements, particularly inspired by Poland’s Solidarity Union, marked a significant shift in the struggle for human rights. However, the response from communist authorities was one of increased repression and propaganda. The government’s efforts to control information and maintain their power ultimately demonstrated the deep fear of change that existed within these totalitarian regimes. As people continued to push for their rights, the foundations for future movements were being laid.

0 notes

Photo

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The signing of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975 brought hope to the nations of the Eastern bloc. This document reaffirmed human rights as a fundamental principle, inspiring people living under totalitarian regimes to seek freedom and justice. It became a powerful tool for those wanting to challenge their governments.

Rise of New Opposition

With the Final Act as a backdrop, a new type of opposition began to emerge across Eastern Europe. More citizens started to openly protest against the restrictions on their rights, demanding that these rights be respected by the communist authorities. The activities of the Solidarity Union in Poland became particularly influential, energizing human rights movements throughout the region.

In the autumn of 1980, inspired by the Polish workers’ struggle for their rights, workers in Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics also began to strike. In Bulgaria, discontent started to surface as well. The government recognized the growing unrest, leading Directorate Six of the Secret Service, which monitored political enemies, to take action. Their task was to prevent any organized opposition that might be influenced by the anti-socialist forces in Poland Rose Festival Tour.

Government Response

By the end of 1980, the Directorate was conducting targeted operations aimed at the intelligentsia, youth, and perceived counter-revolutionaries. The authorities imposed strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and any propaganda materials coming from Poland. This censorship aimed to control the narrative and prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas.

The influx of Polish tourists to Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast during the summer raised alarms for the State Security. The government worried that these visitors might share ideas of dissent with local citizens, further stirring unrest.

Propaganda and Misinformation

To combat the growing influence of Polish movements, the Bulgarian press became a tool for propaganda. The media published distorted accounts of the situation in Poland to mislead the public about the goals of Polish trade unions and the desire of Polish people for democracy. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, frequently reprinted articles from Soviet publications like Pravda and Izvestiya. These articles claimed that Western powers were interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, painting a picture of external threats to justify the regime’s actions.

In conclusion, the signing of the Final Act in 1975 catalyzed a wave of hope and resistance in Eastern Europe. The emergence of new opposition movements, particularly inspired by Poland’s Solidarity Union, marked a significant shift in the struggle for human rights. However, the response from communist authorities was one of increased repression and propaganda. The government’s efforts to control information and maintain their power ultimately demonstrated the deep fear of change that existed within these totalitarian regimes. As people continued to push for their rights, the foundations for future movements were being laid.

0 notes

Photo

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The signing of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975 brought hope to the nations of the Eastern bloc. This document reaffirmed human rights as a fundamental principle, inspiring people living under totalitarian regimes to seek freedom and justice. It became a powerful tool for those wanting to challenge their governments.

Rise of New Opposition

With the Final Act as a backdrop, a new type of opposition began to emerge across Eastern Europe. More citizens started to openly protest against the restrictions on their rights, demanding that these rights be respected by the communist authorities. The activities of the Solidarity Union in Poland became particularly influential, energizing human rights movements throughout the region.

In the autumn of 1980, inspired by the Polish workers’ struggle for their rights, workers in Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics also began to strike. In Bulgaria, discontent started to surface as well. The government recognized the growing unrest, leading Directorate Six of the Secret Service, which monitored political enemies, to take action. Their task was to prevent any organized opposition that might be influenced by the anti-socialist forces in Poland Rose Festival Tour.

Government Response

By the end of 1980, the Directorate was conducting targeted operations aimed at the intelligentsia, youth, and perceived counter-revolutionaries. The authorities imposed strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and any propaganda materials coming from Poland. This censorship aimed to control the narrative and prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas.

The influx of Polish tourists to Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast during the summer raised alarms for the State Security. The government worried that these visitors might share ideas of dissent with local citizens, further stirring unrest.

Propaganda and Misinformation

To combat the growing influence of Polish movements, the Bulgarian press became a tool for propaganda. The media published distorted accounts of the situation in Poland to mislead the public about the goals of Polish trade unions and the desire of Polish people for democracy. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, frequently reprinted articles from Soviet publications like Pravda and Izvestiya. These articles claimed that Western powers were interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, painting a picture of external threats to justify the regime’s actions.

In conclusion, the signing of the Final Act in 1975 catalyzed a wave of hope and resistance in Eastern Europe. The emergence of new opposition movements, particularly inspired by Poland’s Solidarity Union, marked a significant shift in the struggle for human rights. However, the response from communist authorities was one of increased repression and propaganda. The government’s efforts to control information and maintain their power ultimately demonstrated the deep fear of change that existed within these totalitarian regimes. As people continued to push for their rights, the foundations for future movements were being laid.

0 notes

Text

Russia is planning to build a permanent naval base on the Black Sea coast in the breakaway Georgian region of Abkhazia, the region’s leader said.

Abkhazia and Russia have already signed an agreement and the new base will be in the Ochamchira district “in the near future,” Aslan Bzhania, the leader of the occupied Moscow-backed region, told the Izvestiya newspaper in an interview published Thursday.

“All this is aimed at increasing the level of defense capability of both Russia and Abkhazia, and this kind of cooperation will continue, because it ensures the fundamental interests of both Abkhazia and Russia, and security is above all,” he said. “There are also things I can’t talk about.”

News of the new naval base comes a day after the Wall Street Journal reported the Kremlin has withdrawn the bulk of its Black Sea Fleet from its main base in occupied Crimea. Citing Western officials and satellite images, the newspaper wrote that Russia had moved its vessels from Sevastopol — which has been targeted by Ukrainian missiles — to other ports that “offer better protection.”

Abkhazia is one of two breakaway regions in Georgia — the other is South Ossetia — that Moscow unilaterally recognized as independent states in 2008, following a brief war during which Russian forces occupied nearly 20 percent of Georgia’s territory.

The Kremlin’s influence over the region has long been a contentious issue, with thousands of Russian troops still stationed within the territory and along the border with Georgia, which has repeatedly expressed interest in joining both NATO and the EU over the years.

While Abkhazia remains firm in its commitment as an ally of Russia, it has rejected the idea it could be annexed by Russia and insists that it maintains sovereignty.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The signing of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975 brought hope to the nations of the Eastern bloc. This document reaffirmed human rights as a fundamental principle, inspiring people living under totalitarian regimes to seek freedom and justice. It became a powerful tool for those wanting to challenge their governments.

Rise of New Opposition

With the Final Act as a backdrop, a new type of opposition began to emerge across Eastern Europe. More citizens started to openly protest against the restrictions on their rights, demanding that these rights be respected by the communist authorities. The activities of the Solidarity Union in Poland became particularly influential, energizing human rights movements throughout the region.

In the autumn of 1980, inspired by the Polish workers’ struggle for their rights, workers in Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics also began to strike. In Bulgaria, discontent started to surface as well. The government recognized the growing unrest, leading Directorate Six of the Secret Service, which monitored political enemies, to take action. Their task was to prevent any organized opposition that might be influenced by the anti-socialist forces in Poland Rose Festival Tour.

Government Response

By the end of 1980, the Directorate was conducting targeted operations aimed at the intelligentsia, youth, and perceived counter-revolutionaries. The authorities imposed strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and any propaganda materials coming from Poland. This censorship aimed to control the narrative and prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas.

The influx of Polish tourists to Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast during the summer raised alarms for the State Security. The government worried that these visitors might share ideas of dissent with local citizens, further stirring unrest.

Propaganda and Misinformation

To combat the growing influence of Polish movements, the Bulgarian press became a tool for propaganda. The media published distorted accounts of the situation in Poland to mislead the public about the goals of Polish trade unions and the desire of Polish people for democracy. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, frequently reprinted articles from Soviet publications like Pravda and Izvestiya. These articles claimed that Western powers were interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, painting a picture of external threats to justify the regime’s actions.

In conclusion, the signing of the Final Act in 1975 catalyzed a wave of hope and resistance in Eastern Europe. The emergence of new opposition movements, particularly inspired by Poland’s Solidarity Union, marked a significant shift in the struggle for human rights. However, the response from communist authorities was one of increased repression and propaganda. The government’s efforts to control information and maintain their power ultimately demonstrated the deep fear of change that existed within these totalitarian regimes. As people continued to push for their rights, the foundations for future movements were being laid.

0 notes

Photo

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The signing of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975 brought hope to the nations of the Eastern bloc. This document reaffirmed human rights as a fundamental principle, inspiring people living under totalitarian regimes to seek freedom and justice. It became a powerful tool for those wanting to challenge their governments.

Rise of New Opposition

With the Final Act as a backdrop, a new type of opposition began to emerge across Eastern Europe. More citizens started to openly protest against the restrictions on their rights, demanding that these rights be respected by the communist authorities. The activities of the Solidarity Union in Poland became particularly influential, energizing human rights movements throughout the region.

In the autumn of 1980, inspired by the Polish workers’ struggle for their rights, workers in Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics also began to strike. In Bulgaria, discontent started to surface as well. The government recognized the growing unrest, leading Directorate Six of the Secret Service, which monitored political enemies, to take action. Their task was to prevent any organized opposition that might be influenced by the anti-socialist forces in Poland Rose Festival Tour.

Government Response

By the end of 1980, the Directorate was conducting targeted operations aimed at the intelligentsia, youth, and perceived counter-revolutionaries. The authorities imposed strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and any propaganda materials coming from Poland. This censorship aimed to control the narrative and prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas.

The influx of Polish tourists to Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast during the summer raised alarms for the State Security. The government worried that these visitors might share ideas of dissent with local citizens, further stirring unrest.

Propaganda and Misinformation

To combat the growing influence of Polish movements, the Bulgarian press became a tool for propaganda. The media published distorted accounts of the situation in Poland to mislead the public about the goals of Polish trade unions and the desire of Polish people for democracy. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, frequently reprinted articles from Soviet publications like Pravda and Izvestiya. These articles claimed that Western powers were interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, painting a picture of external threats to justify the regime’s actions.

In conclusion, the signing of the Final Act in 1975 catalyzed a wave of hope and resistance in Eastern Europe. The emergence of new opposition movements, particularly inspired by Poland’s Solidarity Union, marked a significant shift in the struggle for human rights. However, the response from communist authorities was one of increased repression and propaganda. The government’s efforts to control information and maintain their power ultimately demonstrated the deep fear of change that existed within these totalitarian regimes. As people continued to push for their rights, the foundations for future movements were being laid.

0 notes

Photo

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

The signing of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975 brought hope to the nations of the Eastern bloc. This document reaffirmed human rights as a fundamental principle, inspiring people living under totalitarian regimes to seek freedom and justice. It became a powerful tool for those wanting to challenge their governments.

Rise of New Opposition

With the Final Act as a backdrop, a new type of opposition began to emerge across Eastern Europe. More citizens started to openly protest against the restrictions on their rights, demanding that these rights be respected by the communist authorities. The activities of the Solidarity Union in Poland became particularly influential, energizing human rights movements throughout the region.

In the autumn of 1980, inspired by the Polish workers’ struggle for their rights, workers in Romania, Georgia, and the Soviet Baltic Republics also began to strike. In Bulgaria, discontent started to surface as well. The government recognized the growing unrest, leading Directorate Six of the Secret Service, which monitored political enemies, to take action. Their task was to prevent any organized opposition that might be influenced by the anti-socialist forces in Poland Rose Festival Tour.

Government Response

By the end of 1980, the Directorate was conducting targeted operations aimed at the intelligentsia, youth, and perceived counter-revolutionaries. The authorities imposed strict censorship on books, newspapers, films, and any propaganda materials coming from Poland. This censorship aimed to control the narrative and prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas.

The influx of Polish tourists to Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast during the summer raised alarms for the State Security. The government worried that these visitors might share ideas of dissent with local citizens, further stirring unrest.

Propaganda and Misinformation

To combat the growing influence of Polish movements, the Bulgarian press became a tool for propaganda. The media published distorted accounts of the situation in Poland to mislead the public about the goals of Polish trade unions and the desire of Polish people for democracy. The official daily newspaper, Rabotnichesko Delo, frequently reprinted articles from Soviet publications like Pravda and Izvestiya. These articles claimed that Western powers were interfering in Poland’s internal affairs, painting a picture of external threats to justify the regime’s actions.

In conclusion, the signing of the Final Act in 1975 catalyzed a wave of hope and resistance in Eastern Europe. The emergence of new opposition movements, particularly inspired by Poland’s Solidarity Union, marked a significant shift in the struggle for human rights. However, the response from communist authorities was one of increased repression and propaganda. The government’s efforts to control information and maintain their power ultimately demonstrated the deep fear of change that existed within these totalitarian regimes. As people continued to push for their rights, the foundations for future movements were being laid.

0 notes

Photo

Bulgaria's Attempt at Peace and the Soviet Declaration of War

Peace Negotiations Begin

On September 2, 1944, the BBC reported that the Bulgarian government had sent a delegation to Cairo to negotiate peace with the Allies. However, despite their efforts, the Bulgarian representatives remained in Cairo, awaiting the armistice terms, which had not yet been provided to them.

A New Government and Continued Efforts for Peace

On the same day, September 2, 1944, a new Bulgarian government was appointed, led by Prime Minister Konstantin Muraviev. This new administration continued the efforts to pull Bulgaria out of the war with the United Kingdom and the United States. The Muraviev government accelerated the peace negotiations and took significant steps toward disengagement from the conflict. They issued an “Amnesty Ordinance,” which granted full amnesty to those who had been persecuted for their political activities. Additionally, the government dissolved the 25th National Assembly and declared Bulgaria’s absolute neutrality in the war Istanbul Tour Guides.

The Soviet Declaration of War

Despite Bulgaria’s attempts to exit the war and maintain neutrality, on September 5, 1944, at 7 p.m., the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria. This declaration came without any provocation from Bulgaria, which had until that point maintained regular diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. Importantly, not a single Bulgarian soldier had participated in any military action on the Eastern Front. The Bulgarian Army’s involvement in the war had been limited to strategic missions in Southeast Europe, anticipating the possibility of a new front. The only Bulgarian forces sent north of the Danube River had been a Red Cross mission, underlining Bulgaria’s limited engagement in the conflict.

International Reactions

The Soviet declaration of war on Bulgaria was met with mixed reactions internationally. On September 5, 1944, Reuters’ diplomatic correspondent Randall Neal commented that the British government had been informed in advance of the Soviet Union’s intentions. Neal suggested that this “realistic step” by the Soviets would help Bulgarians realize the gravity of their situation and possibly expedite the signing of an armistice. He also noted that this move would end Bulgaria’s attempts to avoid paying a significant price for its alliance with Germany. Neal predicted that a new Bulgarian government would need to be formed, likely including left-wing parties and communists, to align with the shifting political landscape.

Soviet Perspective

On September 7, 1944, the Moscow daily Izvestiya commented on the situation, criticizing the Bulgarian authorities for their attempt to maintain ties with Germany while playing with the concept of neutrality. The article warned that such actions could lead Bulgaria into an even deeper crisis.

Bulgaria’s Struggle in a Shifting War

In summary, Bulgaria’s efforts to extricate itself from World War II and establish neutrality were complicated by the broader geopolitical forces at play. Despite attempts to negotiate peace and withdraw from the conflict, Bulgaria found itself the target of a Soviet declaration of war, driven by the complex alliances and strategic interests of the time. The events of early September 1944 marked a critical turning point in Bulgaria’s wartime history, as the nation was forced to confront the harsh realities of its position in the conflict and the consequences of its past alliances.

0 notes