#Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

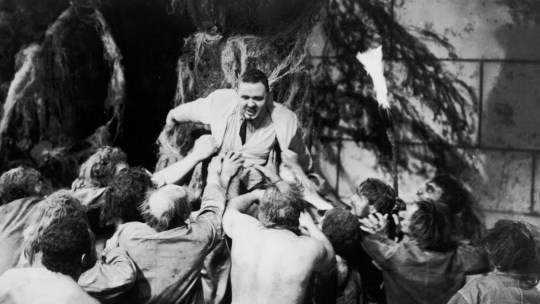

Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

L'île du docteur Moreau

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You! You made us in the house of pain! You made us… things!" Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton My Ko-fi

#Island of Lost Souls (1932)#Island of Lost Souls#Erle C. Kenton#American#science fiction#horror sci-fi#creature feature#my screenshots

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Arlen and Leila Hyams, Island of Lost Souls (dir. Erle C. Kenton, 1932).

#richard arlen#leila hyams#island of lost souls#pre code#1932#halloween films#my edits#mine#halloween

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sci-Fi Saturday: The Invisible Ray

Week 15: The Invisible Ray

Week 15:

Film(s): The Invisible Ray (Dir. Lambert Hillyer, 1936, USA)

Viewing Format: DVD

Date Watched: 2021-09-03

Rationale for Inclusion:

As may be evident by the way I gush over James Whale's films, I am a huge fan of classical era Hollywood horror films. Imagine my delight when I learned that icons of 1930s horror Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi appeared together in not one, but seven films, plus a joint cameo appearance. Seeking out these films is what eventually led me to The Invisible Ray (Dir. Lambert Hillyer, 1936, USA).

The Invisible Ray was the third time Karloff and Lugosi were paired together, not counting their cameo in Gift of Gab (Dir. Karl Freund, 1934, USA). Something I appreciate if you watch the films in chronological order is the horror stars alternating who's the baddie and who's the victimized colleague. Karloff tormented Lugosi in The Black Cat (Dir. Edgar G. Ulmer, 1934, USA), Lugosi tortures Karloff in The Raven (Dir. Lew Landers, 1935, USA), and in The Invisible Ray Karloff's antisocial Dr. Janos Rukh finds himself at odds with or dependent upon Lugosi's Dr. Felix Benet.

As can be surmised from both characters having the title of "doctor," The Invisible Ray like Frankenstein (Dir. James Whale, 1931, USA), Island of Lost Souls (Dir. Erle C. Kenton, 1932, USA), and the other mad scientist films thus far surveyed straddles the line between science fiction and horror. Since better examples of the archetype exist, I would have skipped over The Invisible Ray were it not for the film's plot revolving around a new kind of radiation from the element Radium X. An atomic sci-fi film almost two decades before they became the genre norm absolutely needed to be included in this survey.

Reactions:

Rewatching The Invisible Ray last year as part of a mini chronological survey of 1930s horror, I summed up the movie on microblogging sites as, "Boris Karloff's antisocial scientist pursues Radium X research to the point of self-destruction, but makes the mess he made of his reputation and relationships everyone else's problem." In retrospect, I could just as easily have described the plot with the "instead of going to therapy" meme.

As an early example of atomic sci-fi it presents the extremes that society associated with radiation and radium at the time: Radium X could be a cure-all that benefits society, or deadly poison. Janos Rukh, who previously studied astronomy in an isolated castle with only his mother (Violet Kemble Cooper) and young wife (Frances Drake), the daughter of his former associate, for company, ends up so irradiated whilst investigating the African meteor site source of Radium X that any living creature he touches instantly dies of radiation. His colleague Felix Benet helps Rukh develop a serum to keep the accumulated radiation from cooking him to death, but regular doses must be taken to prevent Rukh from killing himself or others.

In theory, having delayed death, Rukh should be able to continue his life and research without issue. Except all his time away from his wife Diana has alienated her onus based affections, which Rukh takes as a betrayal. Similarly, Benet building upon Rukh's research to develop Radium X into a blindness cure also strikes the irradiated scientist as a betrayal, despite Benet being sure to credit Rukh's work that led to the process. At this point Rukh fakes his own death and starts using his radiation powers to murder off everyone associated with the Radium X African expedition.

While near the end it is implied radiation sickness led to Rukh becoming a serial killer, at the climax his mother shows up to remind him that he was always not of the temperament to live outside of isolation. At which point he agrees with his mother and lets himself cook to death. The Invisible Ray serves up not only an example of an early atomic monster, but that being a mama's boy is tied with being a murderer. (For more on the latter see the filmography of Alfred Hitchcock.)

I typically try to avoid plot synopses in these posts, but the way radiation is shown to have a dual nature in The Invisible Ray makes it stand out compared to other mad scientist and atomic sci-fi. Typically whatever invention a mad scientist is working on comes from good intentions, only to prove disastrous for anyone who comes in contact with it. Radium X being both a cure and danger simultaneously is novel by comparison, and a less reactionary take than atomic sci-fi films made post-atom bomb.

Apart from the novelty of its attitude towards atomic energy, The Invisible Ray is overall forgettable and not very good as a film. Better atomic sci-fi films would follow, and better pairings of Karloff and Lugosi had been made before it and would be made after it (in the latter case specifically Son of Frankenstein (Dir. Rowland V. Lee, 1939, USA) and The Body Snatcher (Dir. Robert Wise, 1945, USA)).

Although, I would be remiss if I did not point out that another novelty in The Invisible Ray is Lugosi got to play a handsome, competent, sane scientist for a change. His filmography usually involves him being obscured by monster makeup or playing an outright villain. As much as I love seeing Lugosi play a monster, I am sorry he rarely got to play more normal, romantic parts like Felix Benet.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloween 2023 marathon: 19-21

The Hands of Orlac (dir. Robert Wiene, 1924)

Concert pianist Orlac (Conrad Veidt) is excited to return from touring to the arms of his loving wife Yvonne (Alexandra Sorina) right before he suffers injuries in a train crash. While the accident does not kill him, it destroys his hands. His hands being key to his livelihood, Orlac despairs, but the doctors are able to graft new ones onto his wrists. All well and good, with one problem: the hands were taken from the corpse of a guillotined murderer, Orlac is uncomfortable with them from the outset, and once he learns of their origins, Orlac is becoming paranoid that the hands will influence him to kill. Driven to madness by his fears, will Orlac resort to violence?

The Hands of Orlac has a great premise and a great lead actor in the compelling, expressive Conrad Veidt. The atmosphere, though not as surreal as Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, is decidedly nightmarish and suffocating as the protagonist's paranoia consumes him.

If only the pacing wasn't the worst.

Like, there's slow pacing and then there's submerging your movie in molasses. Orlac runs almost two hours long and much of it is just dedicated to Veidt's very deliberated mannerisms and reactions. I love Veidt-- he was one of the greatest actors of the silent era-- but the scenes of him staring in horror at his hands and whatnot just go on forever and to no real benefit to the story.

And that's unfortunate because this is a very mature, subdued psychological horror film, more about inner conflict than external monsters or psychopaths (though the movie does ultimately have a villain). In some ways, it's ahead of its time: the urban gloom on display here foreshadows the film noir movies of the 1940s and 1950s. However, it's so slow that I had a hard time getting into it.

The Island of Lost Souls (dir. Erle C. Kenton, 1932)

Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is having a bad week: his ship sank, the captain of the ship that rescued him doesn't like him, and now because of that he's been marooned on the Island of Dr. Moreau, a small bit of land not present on any sea chart. Dr. Moreau (Charles Laughton) seems an amiable, jovial fellow, but what is to be made of the tortured screams in the night or the cowering, abused "natives" who seem to view Moreau as a god? Turns out, Moreau is trying to speed up evolution with his experiments on animals and he hopes to prove his creations can mate with humans by offering Parker his sole female subject, Lota (Kathleen Burke).

The Island of Lost Souls is quintessential pre-code horror, right there with The Most Dangerous Game and the 1932 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. It's gruesome for 1932, dealing with vivisection, inter-species sex, and animal cruelty. Imagine any of THAT flying come the enforcement of the Code.

This is one of very few older horror movies I find genuinely unpleasant even if it doesn't outright show Dr. Moreau cutting up his experiments while they're still very much conscious. Screams are ever present on the soundtrack and they aren't cheesy horror movie yelps. The moans and screaming in this thing are chilling. The humid jungle atmosphere is also palpable, creating a sense of suffocating entrapment. As much as I love many of the classic Universal horror movies, they don't have that same sense of dread and evil this one still possesses.

The Penthouse (dir. Peter Collinson, 1967)

Crooked businessman Bruce (Terence Morgan) and his shopgirl mistress Barbara (Suzy Kendall) find themselves at the mercy of two thugs who break into the penthouse apartment they use for their adulterous liaisons. Tom (Tony Beckley) and Dick (Norman Rodway) are childlike yet ruthless, getting Barbara intoxicated while they tie Bruce up and make him watch. Or rather listen, because boy do these fellas love monologuing.... lots and lots and lots of monologuing.

Yes, the guy who directed The Italian Job made a home invasion movie. It also sucks. Like, oh my GOD, this was designed to torture me, I swear, and not in the way the filmmakers intended. It feels like a college assignment turned into a movie.

Okay, let me be nice first. Visually, this is of interest. Not the quality of the image-- the YouTube upload looks like it was dragged up from VHS hell-- but from what I can see of the compositions and the camerawork, this is a visually dynamic movie doing its hardest to make you forget the script is based on a stage play.

But that's impossible because this is one of those movies where the characters never shut the hell up. They monologue endlessly about Societal Ills and Important Class Themes, occasionally breaking up the lecturing with oddball criminal antics, pot smoking, and violence. It's like an attempt at a "hipper" (for 1967) and more intellectual version of The Desperate Hours, where an ordinary middle-class family is held hostage by criminals as motivated by class-based bitterness as they are by money or freedom. But holy crap, does. It. Drag. 100 minutes of dragging.

Admittedly, the dynamic between Tom and Dick is a little interesting. They're the types who finish each other's sentences and genuinely seem to relish each other's company as they bond over doing these terrible things. They were fascinating to watch when not burdened with pretentious monologues about how baby alligators being flushed down toilets represent society's outliers.

Martine Beswick shows up in the last section as the third accomplice "Harry." Other reviewers claim she brightens up the film, but her appearance is so brief and much ado about nothing at all that she didn't make watching this any more entertaining for me.

The Penthouse feels like a parody of the worst kind of "elevated horror," boring nonsense masquerading as a social statement. Parts of it are memorably bizarre, but there's not enough of that for me to recommend it.

#halloween 2023 marathon#thoughts#the hands of orlac#the island of lost souls#the penthouse#i feel so much of this is negative and i apologize#but man hands of orlac and the penthouse let me down

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

31 days of halloween (2/31)

Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

what is the law?

#bela lugosi#erle c kenton#1932#1930s#science fiction#sci-fi#pre-code#pre-code hollywood#charles laughton#dr moreau#oldhollywoodedit#horror#halloween2022#remember2022#halloween

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

#horroredit#cinemaspam#classicfilmblr#oldhollywoodedit#userhorroredits#classicfilmsource#filmgifs#filmedit#island of lost souls#criterion#1930s#film#gif

385 notes

·

View notes

Text

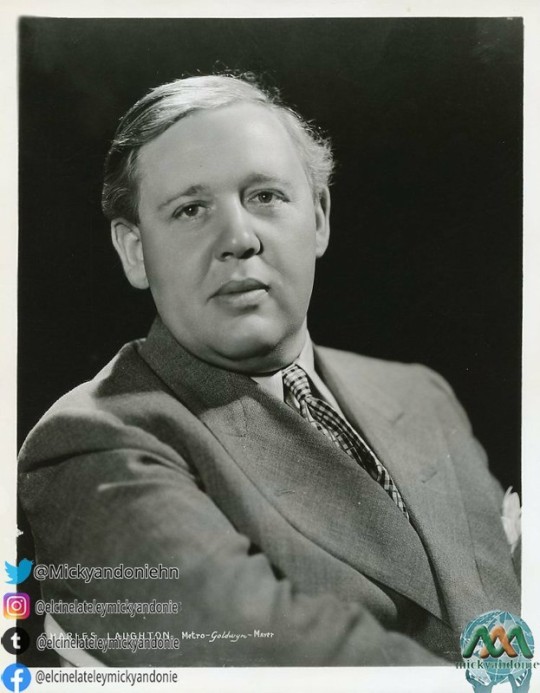

Charles Laughton.

Filmografía

Películas

- Bluebottles, The Tonic, Daydreams (1928) Dir.: Ivor Montagu

- Piccadilly (1929) Dir.: Ewald Andrea Dupont.

- Wolves (1930).

- Down River (1931) Dir. Peter Godfrey

-El caserón de las sombras (The Old Dark - House, 1932) Dir. James Whale

- Entre la espada y la pared (The Devil and the Deep, 1932) Dir. Marion Gering

- Justicia divina/El asesino de Mr. Medland (Payment Deferred, 1932) Dir. Lothar Mendes

- El signo de la cruz (The Sign of the Cross, 1932) Dir. Cecil B. De Mille

- Si yo tuviera un millón (If I Had a Million, 1932) Dirs. Ernst Lubitsch, Norman Taurog, Stephen Roberts, Norman McLeod, James Cruse, William A. - Seiter y H. Bruce Humberstone

- La isla de las almas perdidas (Island of Lost Souls, 1932) Dir. Erle C. Kenton

- La vida privada de Enrique VIII (The Private Life of Henry VIII, 1933) Dir. Alexander Korda

- White Woman (1933) Dir. Stuart Walker

- The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934) Dir. Sidney Franklin

- Nobleza obliga (Ruggles of Red Gap, 1935) Dir. Leo McCarey

- Los miserables (Les Misérables, 1935) Dir. Richard Boleslawsky

- Rebelión a bordo (Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) Dir. Frank Lloyd

- Rembrandt (Rembrandt, 1936) Dir. Alexander Korda

- Yo, Claudio (I, Claudius, 1937) Dir. Joseph von Sternberg.

- Bandera amarilla (Vessel of Wrath, 1938) Dir. Eric Pommer (Laughton es actor y coproductor de esta película).

- Las calles de Londres (St. Martin's Lane, 1938) Dir. Tim Whelan (Laughton es actor y coproductor de esta película).

- La posada de Jamaica (Jamaica Inn, 1939) Dir. Alfred Hitchcock (Laughton es actor y coproductor de esta película).

- Esmeralda, la zíngara (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1939) Dir. William Dieterle

- Laughton en la película Ellos sabían lo que querían (1940), con Carole Lombard y Frank Fay.

- They Knew What They Wanted (1940) Dir. Garson Kanin

- Casi un ángel (It Started with Eve, 1941) Dir. Henry Koster

- Se acabó la gasolina (The Tuttles of Tahiti, 1942) Dir. Charles Vidor

- Seis destinos (Tales of Manhattan, 1942) Dir. Julien Duvivier

- Stand by for Action (1943) Dir. Robert Z. Leonard

- Forever and a Day (1943) Dirs. René Clair, Edmund Goulding, Cedric Hardwicke, Frank Lloyd, Victor Saville.

-Esta tierra es mía (This Land Is Mine, 1943) Dir. Jean Renoir

- The Man from Down Under (1943) Dir. Robert Z. Leonard

- The Canterville Ghost (1944) Dir. Jules Dassin

- El sospechoso (The Suspect, 1944) Dir. Robert Siodmak

- El capitán Kidd (Captain Kidd, 1945) Dir. Rowland V. Lee

- Su primera noche (Because of Him, 1946) Dir. Richard Wallace

- Arco de triunfo (Arch of Triumph, 1947) Dir. Lewis Milestone

- El reloj asesino (The Big Clock, 1947) Dir. John Farrow

- El proceso Paradine (The Paradine Case, 1948) Dir. Alfred Hitchcock

- On our Merry way/A Miracle can Happen (1948) Dirs. King Vidor, Leslie Fenton, John Huston, George Stevens.

- The Girl from Manhattan (1948) Alfred E. Green

- Soborno (The Bribe, 1949) Dir. Robert Z. Leonard

- El hombre de la torre Eiffel (The Man on the Eiffel Tower, 1949) Dir. Burgess Meredith (codirectores no acreditados: Charles Laughton y Franchot Tone).

- No estoy sola (The Blue Veil, 1951) Dir. Curtis Bernhardt

- The Strange Door (1951) Dir. Joseph Pevney

- Cuatro páginas de la vida (O. Henry's Full House, 1952) Dir. Henry Koster

- Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd (1952) Dir. Charles Lamont

- Salomé (Salome, 1953) Dir. William Dieterle

- La reina virgen (Young Bess, 1953) Dir. George Sidney

- El déspota (Hobson's Choice, 1954) Dir. David Lean

- La noche del cazador (The Night of the Hunter, 1954) Dir. Charles Laughton (no aparece como actor en la película).

T- estigo de cargo (Witness for the Prosecution, 1957) Dir. Billy Wilder

- Bajo diez banderas (Sotto dieci bandiere, 1960) Dir. Diulio Colletti

Espartaco (Spartacus, 1960) Dir, Stanley Kubrick

- Tempestad sobre Washington (Advise and Consent, 1962) Dir. Otto Preminger.

Documentales

- The Epic That Never Was (1965). Dirigido por Bill Duncalf y presentado por Dirk Bogarde. Documental de la BBC sobre el rodaje de I, Claudius con diversas escenas acabadas. (VHS, DVD).

- Callow's Laughton (1987). Documental de la Yorkshire TV-ITV dirigido por Nick Gray y presentado por Simon Callow sobre Charles Laughton.

- Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter (2002). Documental dirigido por Robert Gitt a partir de tomas descartadas de la Película.

Teatro

Debut teatral (1913). Stonyhurst College, Reino Unido

- The Private Secretary per Charles Hawtrey

Teatro amateur (hasta 1925). Scarborough, Reino Unido

- The Dear Departed por Stanley Houghton

- Trelawney of The Wells por Arthur Wing Pinero

- Hobson's Choice por Harold Brighouse

1926

- The Government Inspector. por Nicolai Gogol. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Los puntales de la sociedad por Henrik Ibsen. Dir. Sybil Arundale

- El jardín de los cerezos por Antón Chéjov. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Las tres hermanas por Antón Chéjov. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Liliom por Ferencz Molnar. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

1927

- The Greater Love por James B. Fagan. Dir. James B. Fagan y Lewis Casson

- Angela por Lady Bell. Dir. Lewis Casson

Vestire gli ignudi por Luigi Pirandello. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Medea por Eurípides. Dir. Lewis Casson

- The Happy Husband por Harrison Owen. Dir. Basil Dean

- Paul Y por Dimitri Merejovski. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Mr. Prohack por Arnold Bennet y Edward Knoblock. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

1928

- A Man with Red Hair por Benn W. Levy, a partir de la novela de Hugh Walpole. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- The Making of an Immortal por George Moore. Dir. Robert Atkins

- Riverside Nights por Nigel Playfair y A.P. Herbert. Dir. Nigel Playfair

- Alibi per Michael Morton, a partir de la novela de Agatha Christie. Dir. Gerald duMaurier

- Mr. Pickwick por Cosmo Hamilton y Frank C. Reilly, a partir de la novela de Charles Dickens. Dir. Basil Dean

1929

- Beauty por Jacques Deval (adapt. inglesa: Michael Morton). Dir. Felix Edwardes

- The Silver Tassie por Sean O'Casey. Dir. Raymond Massey

1930

- French Leave por Reginald Berkeley. Dir. Eille Norwood

- On the Spot por Edgar Wallace. Dir. Edgar Wallace

1930

- Payment Deferred por Jeffrey Dell, a partir de la novela de C.S. Forrester. Dir. H.K. Ailiff

1931

-Gira americana (Chicago y Nueva York) de Payment Deferred y Alibi (esta última retítulada The Fatal Alibi y dirigida por Jed Harris).

Old Vic: temporada 1933-34. Londres. Reino Unido. Todas las obras dirigidas por Tyrone Guthrie.

El jardín de los cerezos por Antón Chéjov. Dir. Charles Laughton

1951-52 Estados Unidos y Reino Unido (Gira).

Don Juan in Hell de Man and Superman por George Bernard Shaw. Dir. Charles Laughton.

1953 Estados Unidos (Gira).

John Brown's Body por Stephen Vincent Benet. Dir. y Adaptación: Charles Laughton (no apareció como actor).

1954 Estados Unidos (Gira).

The Caine Mutiny Court Martial por Herman Wouk, a partir de su novela. Dir. Charles Laughton (no apareció como actor).

1956 Nueva York, Estados Unidos.

Major Barbara por George Bernard Shaw. Dir. Charles Laughton

1956 Londres, Reino Unido

The Party por Jane Arden. Dir. Charles Laughton

1959 Stratford-upon-Avon, Reino Unido

El sueño de una noche de verano por William Shakespeare. Dir. Peter Hall

El rey Lear por William Shakespeare. Dir. Glen Byam Shaw.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Laughton

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

island of lost souls (1932) dir. erle c kenton

chinese odyssey 2002 (2002) dir. jeffrey lau

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Island of Lost Souls (1932) dir. Erle C. Kenton

#island of lost souls#erle c kenton#kathleen burke#horrorstills#horroredit#1930s#horror#caps#*#*iols

247 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alternatives to Modern Horror (the slasher…)

Nosferatu (1922)

Dir. F. W. Murnau

Starring: Max Schrek, Gustav von Wangenheim, and Greta Schröder

The Bela Lugosi Dracula is iconic and Gary Oldman’s interpretation is also amazing, but to me the definitive vampire is Nosferatu “Count Orlok”. Max Schrek is absolutely terrifying and Murnau’s usage of shadows is heightened by the almost ethereal lighting of these old prints.

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

Dir. Rupert Julian

Starring: Lon Chaney, Mary Philbin, and Norman Kerry

Popularized of late by the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, this original adaption of the novel is much closer to the novel I am told and far more thrilling. Lon Chaney “the man of a thousand faces” is at the height of his skill here crafting one of the best makeup jobs for the phantom I have seen. Something about the black and white filming helps heighten the terror for many of these films.

The Island of Lost Souls (1932)

Dir. Erle C. Kenton

Starring: Charles Laughton, Bela Lugosi, Richard Arlen, and Kathleen Burke

One of the first adaptions of The Island of Dr. Moreau, this is my favorite version because it does not get too bogged down in the philosophical themes. It is fairly straight forward and still a bit creepy and chilling. Made before the Hays Code it was considered shocking at the time and was originally banned in the UK.

Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954)

Dir. Jack Arnold

Starring: Richard Carlson, Julie Adams, and Richard Denning

Can be counted among the classic movie monsters of Universal along with Dracula, The Wolf Man, and The Invisible Man, this monster film is unique for its underwater sequences and incredible creature suit. Not quite as terrifying as the others on this list, but more a fun monster film in the vein of The Wolf Man (1941) also one to watch if you have not seen it.

#Nosferau#Halloween#The Phantom of the Opera#The Island of Lost Souls#Creature from the Black Lagoon

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

365 Day Movie Challenge (2017) - #325: Island of Lost Souls (1932) - dir. Erle C. Kenton

My literary pursuits aren’t what they used to be when I was a teenager, so I’m not actually familiar with H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreau. Sure, I had heard of it, and I knew that there was a legendarily weird film version from 1996 that was directed by John Frankenheimer and starred Marlon Brando, but the extent of my Wells knowledge comes from watching cinematic adaptations of his work and from knowing a few facts about his personal life, like that he had an affair with the writer Rebecca West (please read The Return of the Soldier if you haven’t!) and that they had a son out of wedlock, Anthony West, who became an acclaimed author in his own right.

I’m glad, therefore, that Island of Lost Souls turned out to be a highly entertaining horror film. I shouldn’t have expected anything less; the cast includes Charles Laughton, Bela Lugosi, Kathleen Burke (the beguiling actress who intrigued me with her work in 1933′s Murders in the Zoo) and Arthur Hohl, as well as less compelling but still basically dependable performers Richard Arlen and Leila Hyams. Like another horror-adventure film that came out in 1932, The Most Dangerous Game, the plot of Island of Lost Souls concerns a young man (Arlen) who is stranded on an island ruled by a madman (Laughton). Swap out human-hunting for experimentation on human beings, and that’s Island of Lost Souls.

Laughton is, as always, deliciously hammy here. The man knew the precise way to deliver a line so that it walked right on the edge of wit and silliness, always knowing how to wring the maximum impact out of each word and syllable. His towering performance cannot be matched by the rest of the cast - Arlen is a bland hero and Hyams barely registers at all as his love interest - but Bela Lugosi’s small role as the island’s “Sayer of the Law” is certainly memorable. Besides repeatedly reciting the famous line “Are we not men?” (familiar to anyone who likes Devo), Lugosi delivers an impassioned speech at the end of the film in one of the best dramatic moments that he ever committed to film. Island of Lost Souls also benefits from luminous black-and-white cinematography by Karl Struss, the DP who lit Sunrise, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Sign of the Cross, The Story of Temple Drake, The Great Dictator, Limelight and the original 1958 version of The Fly.

#365 day movie challenge 2017#island of lost souls#1932#1930s#30s#erle c. kenton#old hollywood#pre-code#pre code#precode#horror cinema#horror film#horror films#horror movies#charles laughton#bela lugosi#lugosi#kathleen burke#arthur hohl#richard arlen#leila hyams#karl struss

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sci-Fi Saturday: The Invisible Man

Week 12:

Film(s): The Invisible Man (Dir. James Whale, 1933, USA)

Viewing Format: DVD

Date Watched: August 13, 2021

Rationale for Inclusion:

After a diversion into aeronautic sci-fi and a post-apocalyptic narrative, our survey returns for one last example of a Pre-Code horror hybrid: The Invisible Man (Dir. James Whale, 1933, USA).

As with Island of Lost Souls (Dir. Erle C. Kenton, 1932, USA), The Invisible Man is based on an H.G. Wells novel. Unlike when Paramount Pictures bought the rights to adapt The Island of Dr. Moreau, however, Wells demanded script approval as part of the deal with Universal Studios for them to adapt The Invisible Man. Wells had hated the adaptation of The Island of Dr. Moreau, finding its emphasis on horror and lack of imagination miserable, and was not going to let a similar fate befall another one of his novels.

Although the rights were secured by Universal not long after the success of Dracula in 1931, it would take two years for the studio to assemble a satisfactory crew, script and cast. James Whale signed onto the project in 1931, but after the huge success of Frankenstein (1931, USA) left the project, not wanting to be associated as a horror director. However, after his return to romance with The Impatient Maiden (1932, USA) failed at the boxoffice, Whale returned to horror, first with The Old Dark House (1932, USA), which reunited him with Boris Karloff, and then signing back on to The Invisible Man. During Whale's absence from the project many screenwriters and drafts of screenplays, some of which used elements from another novel that Universal bought the rights to, The Murderer Invisible by Philip Wylie, had come and gone and failed to meet with Wells' approval.

In June of 1933, a script that finally met with Wells' approval was produced by R. C. Sherriff, who had written the play Journey's End, which sent Whale's star on the rise. This screenplay originated the idea that the experimental monocane serum that Dr. Jack Griffin (Claude Rains) produces not only makes him invisible, but slowly destroys his sanity. Similar to the lab setup and lightning power in Whale's Frankenstein, insanity as a byproduct of the invisibility would inform later adaptations of the Wells novel, including the early 2000s television series, which also featured a clip from the 1933 film in its opening credits sequence.

Reactions:

As resistant as Whale initially was to making horror films after Frankenstein, he proved with each subsequent one that he made how good he was at it. With the help of a group of repertory creatives both on and off screen, Whale put a pathos and humor into his horror films in a way that no other director working in the genre in the 1930s did. It's why over 90 years later Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Invisible Man, and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, USA) are some of the best horror films of their era and amongst the most influential of all time.

Yet, the horror genre aspects in The Invisible Man are not as prominent as its science fiction categorization. Griffin is a mad scientist, that is an otherwise average person, whose hubris and curiosity makes a monster out of him. My partner noted that he considers The Invisible Man to definitely be a monster movie, but more of a suspense or mystery film than a horror film. Any movie that features a serial killer is at least partially horror in my reckoning, but the way the narrative of The Invisible Man unfolds, it is closer to a suspense film like M (Dir. Fritz Lang, 1931, Germany) than an unquestioned horror film with a fantasy monster like Dracula (Dir. Tod Browning, 1931), despite all three having narratives that boil down to "what is the mystery surrounding this man" then "this man is a monster and must be destroyed for the greater good."

The mystery and monstrosity around Griffin is rendered possible through the performance of Claude Rains and some inventive special effects. As with Whale's casting of Karloff in Frankenstein, his role as the title character in The Invisible Man was a star-making role for theater actor Rains. Having to rely on his voice and physicality, but not his face, gave Rains some trouble during production, but he ultimately created a character that oscillates between aloofly mysterious and a madcap lunatic.

A combination of post-production optical work, clever blocking, and use of wires rendered Griffin invisible. The special effects used would remain the standard way of conveying an invisible entity prior to computer generated imagery and post-production work becoming dominant in the industry. As silly as it may feel knowing that Griffin unwraps his head revealing nothing beneath is achieved by something as simple as Rains wearing his shirt and jacket above his head as he removes the bandages it remains visually iconic.

My only issue with the practical special effects comes at the film's climax when Griffin exits the cabin where he is hiding out and he leaves shoe prints in the snow, despite it being previously established that to be fully invisible (as he is in the scene) he must be totally naked. What baffles me if the use of shoe prints instead of footprints was a question of deliberate censorship or thoughtless oversight. I usually don't get nitpicky about these types of goofs in movies, but it stands out sharply in an otherwise carefully engineered film.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kathleen Burke in: Island of Lost Souls (Dir. Erle C. Kenton, 1932). Source

111 notes

·

View notes