#Irrigation Systems in Gold Coast

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

#Retaining Walls Gold Coast#Irrigation Systems in Gold Coast#Affordable Landscape Contractors Gold Coast

0 notes

Text

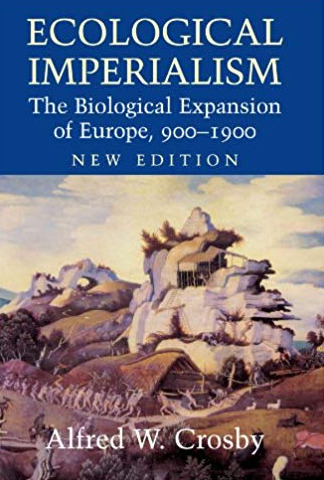

Open Veins of Latin America Ch. 1

...Exiled in their own land, condemned to an eternal exodus, Latin America’s native peoples were pushed into the poorest areas— arid mountains, the middle of deserts— as the dominant civilization extended its frontiers. The Indians have suffered, and continue to suffer, the curse of their own wealth, that is the drama of all Latin America. When placer gold was discovered in Nicaragua’s Rio Bluefields, the Carca Indians were quickly expelled far from their riparian lands, and the same happened with the Indians in all the fertile valleys and rich-subsoil lands south of the Rio Grande. (47)

...The conquest shattered the foundations of these civilizations. The installation of a mining economy had direr consequences than the fire and sword of war. The mines required a great displacement of people and dislocated agricultural communities; they not only took countless lives through forced labor, but also indirectly destroyed the collective farming system. The Indians were taken to the mines, were forced to submit to the service of the encomenderos, and were made to surrender for nothing the lands which they had to leave or neglect. On the Pacific coast the Spaniards destroyed or let die out the enormous plantations of corn, yucca, kidney and white beans, peanuts, and sweet potato; the desert quickly devoured great tracts of land which the Inca irrigation network had made abundant. Four and a half centuries after the Conquest only rocks and briars remain where roads had once united an empire. Although the Incas’ great public works were for the most part destroyed by time or the usurper’s hand, one may still see across the Andean cordillera traces of the endless terraces which permitted, and still permit, cultivation of the mountainsides. A U.S. technician estimated in 1936 that if the Inca terraces had been built by modern methods at 1936 wage rates they would have cost some $30,000 per acre. In that empire which did not know the wheel, the horse, or iron, the terraces and aqueducts were made possible by prodigious organization and technical perfection achieved through wise distribution of labor, as well as by the religious force that ruled man’s relation with the soil—which was sacred and thus always alive. (43)

1 note

·

View note

Text

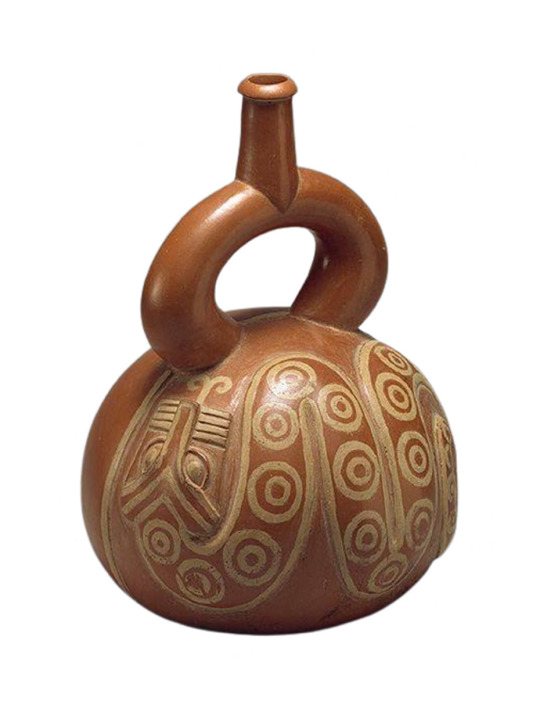

@edisonblog The Moche Culture, also known as the Mochica Culture, was an ancient pre-Columbian civilization that flourished on the northern coast of Peru between AD 100 and 800. Its territory covered what is now part of the departments of La Libertad and Lambayeque. The Mochicas were an advanced people who made great advances in various fields, leaving behind a significant cultural and archaeological legacy.

Among the most outstanding characteristics of the Moche Culture are:

Exceptional ceramics: The Mochicas were masters of ceramics. They created beautiful decorative and utilitarian pieces, often representing scenes from daily life, religious ceremonies, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures, and portraits of important people. Their ability to sculpt in clay allowed them to capture realistic and expressive details.

Complex engineering works: The Mochicas built irrigation systems to take advantage of the water from the rivers and ensure the irrigation of their agricultural fields. This allowed them to develop an economy based on agriculture and fishing.

Art and religion: Religion played an important role in the life of the Mochicas. Their art was heavily influenced by their beliefs, and they represented their gods, priests, warriors, and mythological beings in their ceramics and murals.

Hierarchical society: Mochica society was structured into social classes, with a ruling elite that held political, religious, and military power. The rulers were considered demigods and their authority was centralized.

Advances in metallurgy: The Mochicas were also expert metallurists and worked with gold, silver, and copper. They created ornaments, jewelry and ceremonial objects with great skill.

Funeral complexes: The Mochicas built adobe pyramids known as "huacas" that served as funerary complexes and ceremonial centers. In these huacas, they buried their rulers and elite, accompanying them with rich treasures and offerings.

Although the Moche Culture disappeared more than a thousand years ago, its cultural legacy has been rediscovered and studied by modern archaeologists and historians. Its impressive artistic and technological achievements continue to amaze the world and provide valuable insights into the region's rich pre-Columbian history.

#edisonmariotti Edison Mariotti Edison Mariotti by by Alejandro A Mendoza link: https://shre.ink/aF6Z

.br

A Cultura Moche, também conhecida como Cultura Mochica, foi uma antiga civilização pré-colombiana que floresceu na costa norte do Peru entre 100 e 800 DC. Seu território cobria o que hoje faz parte dos departamentos de La Libertad e Lambayeque. Os Mochicas foram um povo avançado que fez grandes avanços em vários campos, deixando um legado cultural e arqueológico significativo.

Entre as características mais marcantes da Cultura Moche estão:

Cerâmica excepcional: Os Mochicas eram mestres da cerâmica. Eles criaram belas peças decorativas e utilitárias, muitas vezes representando cenas da vida cotidiana, cerimônias religiosas, figuras antropomórficas e zoomórficas e retratos de pessoas importantes. Sua capacidade de esculpir em argila permitiu-lhes capturar detalhes realistas e expressivos.

Complexas obras de engenharia: Os mochicas construíram sistemas de irrigação para aproveitar a água dos rios e garantir a irrigação de seus campos agrícolas. Isso lhes permitiu desenvolver uma economia baseada na agricultura e na pesca.

Arte e religião: A religião desempenhou um papel importante na vida dos Mochicas. Sua arte foi fortemente influenciada por suas crenças, e eles representavam seus deuses, sacerdotes, guerreiros e seres mitológicos em suas cerâmicas e murais.

Sociedade hierárquica: A sociedade mochica era estruturada em classes sociais, com uma elite dirigente que detinha o poder político, religioso e militar. Os governantes eram considerados semideuses e sua autoridade era centralizada.

Avanços na metalurgia: Os Mochicas também eram metalúrgicos especializados e trabalhavam com ouro, prata e cobre. Eles criaram ornamentos, joias e objetos cerimoniais com grande habilidade.

Complexos funerários: Os Mochicas construíram pirâmides de adobe conhecidas como "huacas" que serviam como complexos funerários e centros cerimoniais. Nessas huacas enterraram seus governantes e elites, acompanhando-os com ricos tesouros e oferendas.

Embora a Cultura Moche tenha desaparecido há mais de mil anos, seu legado cultural foi redescoberto e estudado por arqueólogos e historiadores modernos. Suas impressionantes realizações artísticas e tecnológicas continuam a surpreender o mundo e fornecem informações valiosas sobre a rica história pré-colombiana da região.

0 notes

Text

The Martuwarra (Fitzroy) River system winds its way through Western Australia’s Kimberley region, along deep troughs and shallow rivulets, nourishing a complex and finely tuned ecosystem as well as the culture and cosmology of the local traditional owners.

The river is fed by 20 tributaries and flows through three shires across the lands of seven different Indigenous nations, before emptying into the Indian Ocean at King Sound.

For Dr Anne Poelina, a Nyikina Warrwa Indigenous academic and researcher who advocates to protect the river, the Martuwarra is home, and a living ancestor.

“It’s the construction of our whole identity,” Poelina says. “It’s the river of life.”

Last Tuesday, the Western Australian State Government closed the public submission period for decision-making on the Martuwarra’s hydrological future. The submissions were canvassed in response to the State Government’s November 2020 paper, Managing Water in the Fitzroy River Catchment, that outlined its proposals for the future of the river system. [...]

Some have expressed fears that under the auspices of government, and pushed by bastions of industry, the river could go the way of the Murray-Darling Basin, drained of water and lifeblood thanks to overzealous irrigation practices. [...]

Among the pastoralists and landholders vying for access to the Fitzroy’s aquatic gold is Australia’s richest person, multi-billionaire Gina Rinehart, who wants to divert water from the river for her Liveringa cattle station.

But the Fitzroy river, like all river systems in the arid, monsoonal Kimberley, is seasonal and unpredictable: in a given year it may flood, filling the entire system, but it also may not. In these in-between times, local species rely on remnant pools to survive until the next flood event, leaving these ecosystems in a precarious balancing act. [...]

The Martuwarra is home to several vulnerable and unique species, including the endangered sawfish, one of Western Australia’s iconic species, which relies on wet-season deluges and which is already imperilled by the prospect of more frequent droughts and climate change. David Morgan is a researcher in aquatic ecosystems at Murdoch University, and a specialist in the unique fish life of the Martuwarra. “A lot of people think ‘oh, it’s just a river’, but they don’t understand the importance of this river to these globally threatened species,” Morgan says. Because the Martuwarra is seasonal, the fish in its waterways rely on periodic deluges for their survival. [...]

Many of those expressing concerns about developments to the Martuwarra point to the Murray-Darling Basin catastrophe as a lesson in what not to do. Blighted by a cocktail of factors including extreme drought, decades of irrigation and – some argue – poor management practices, the basin no longer has the water required to support itself. The basin, which produces a third of Australia’s food, has in recent years suffered from mass fish kills, prolonged periods of utter dryness, and the depletion of its ecosystems. [...]

-------

Adam Rose is a specialist in water systems and water ecology at Central Queensland University. While his research focuses on the tropical water systems of the Queensland coast, Rose says Australia’s water systems share fundamental similarities that make working with them unique and complex.

“Australia is the driest inhabited continent on Earth,” Rose says. “Years ago, before colonisation, everything was different – the soils were different, we didn’t have hard-hooved animals, and so when it would rain it would soak into the environment and filter through these soils and get to our creeks and rivers.

“All of our plants and animals have evolved under these conditions, and then the white fella arrives and brings these two traditional European farming methods, clearing all of the trees and introducing animals.

“Just in that we changed that water cycle.”

Rose says proper management of our embattled water systems requires relying on traditional knowledge systems, rather than top-down governance.

“I want to know some of the old stories about what plants and what fish were where in the traditional stories,” he says. “Instead of having Canberra tell us what to do, I think we should be joining forces with the traditional owners, getting the farmers and the scientists to actually do the research in that catchment together and start to make local decisions for the catchment.” [...]

“The Bureau of Meteorology is saying we need to learn to live with less water, and yet the approach (being proposed) is to look at how do we swallow up as much water from the system as possible,” Poelina says. Traditional owners, on the other hand, “live under a law of the river, a law of obligation to protect the river because it is the river of life”. From her perspective, the Martuwarra has vital importance not just to its traditional custodians but to the nation and the planet, too. “It’s a national heritage site, and it’s the largest listed Western Australian Aboriginal cultural heritage site, so it belongs to our fellow Australians and it belongs to the world, too. We don’t want a repeat of Juukan Gorge in the destruction of our sacred site.”

-------

Headline, image, caption, and text published by: Amalyah Hart. “The fight for the Martuwarra.” Cosmos. 2 September 2021.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ev’s Homeland Lore

Trivia

Zadith - the country’s name might be a reference to Egyptian alchemist known in Latin as Senior Zadith. [tumblr likes to delete my external links but it’s on wiki]

Language - Zadithi, but demonym and adjective - Zadithian. No, I don’t know why

Cyrenice - the city’s name is created by combining names of two Ancient Greek and later Roman cities located in North Africa- Cyrene (modern day eastern Libya) and Berenice (modern day Egypt).

Some visuals are here.

Zadith

Zadith is a relatively large country bordered by the vast mountain ranges from the north to south-east and the sea on another side. It includes a dozen of islands (most of which are too small to be marked on the map below) off its south-western coast.

The population seems to concentrate in the western and southern areas, with the rest of the country’s territory being covered by Fenekh Desert and difficult terrain of highlands where human settlements are very sparse. Although the conditions there are harsh and not suitable for agriculture (except few oases), the area is rich in natural resources: with salt lakes and rich deposits of ores, such as gold, iron, copper, silver, as well as gems, limestone and marble.

Most of the south-west of the country benefits from the mild meditarenian climate with hot, dry summers and short and rainy winters. Wild olive trees are abundant, and large areas of oak and cyprus savanna provide pasture to the flocks and herds of the local farmers. Various fruit trees, almonds, grapes, wheat and barley are historically grown in the region.

The country has five main cities which also function as capitals of the provinces:

Zoar - the official capital of the country and its political centre which lies in a lush river valley;

Cyrenice - ancient seaside city and port known as academic and cultural centre;

Admah - remote mystic city on the step of the Clouded Mountains;

El-Kochab - eight angled star-shaped city hidden behind tall stone walls, home to the largest market in the country;

Tarut - capital of the island Thera and the biggest port on Zadithian islands.

Although it is not as multicultural as Vesuvia, Zadith was formed by the union of the formerly independent countries and later expanded further absorbing other city states and tribes, all being quite diverse culturally and ethnically. (Ev’s and Asra’s families have completely different backgrounds). The administrative regions of the country seem to broadly reflect those differences.

Zadithi is a common and official language, however the secondary native languages are still widely used in informal settings in certain areas.

The country is ruled by two equal Viziers (monarchs coming from two unrelated dynasties), each holding a veto over the other’s actions. The powers of Viziers are held in check by Ephors (form of parliament with 5 representatives of 5 provinces, the way those representatives are chosen varies by province). Each province is ruled by local governor and Zadithian history knows many instances in which the governors acted independently, and even in opposition to the rulers.

Zadith is considered a technologically advanced nation: there are complex irrigation and water supply systems, firearms are available to elite military, medicine is well developed, great strides have been made in the fields of chemistry and metallurgy. Due to the local conditions and farming not being predominant, the country is unable to export much of its agricultural produce (with exception to oil, cotton, linen). Zadith is most known for its luxury goods and crafts, such as fine fabrics, clocks, ceramics, spices, glassware, iron, jewelry and raw precious metals and gems. In many countries the word Zadithian is synonymous with innovative design and intricate craftsmanship. Zadith is also a well known place for headhunting when foreign nobility or royalty require teachers, scholars or any other skilled professionals.

Magic and mysticism are very common in Zadith: almost every household’s door has a protective charm on it and magical rituals are an essential part of the country’s festivals and celebrations. Magical creatures such as genies and phoenixes still live in the rural areas and some of them serve the most powerful magicians coming from Fenekh Desert and Clouded Mountains.

Both magic and science are highly respected in Zadith, but ‘intellectuals’ as a class still stand below nobility, religious leaders, who hold the political power in the country, and are not as wealthy as most of the merchants and landowners. Although knowledge and education is highly praised in Zadith, academic institutions are not that well developed. Most people study through private home tuition and apprenticeships. Popular and well developed academic disciplines as mathematics, physics, chemistry, geography, history and languages.

Zadith has complex currency and measurement systems, public holidays and customs vary by province which does not make trade with the country very straightforward. It is also known for not the most effective administration and tedious bureaucracy: if a foreigner wants to open business or pay taxes in Zadith, they are most inevitable going to go through at least 5 officials, fill in 15 forms and wait long time because the office that they need is either closed for the afternoon break (it’s hot country, they have siesta) or all the right people are off work celebrating something in their hometowns.

Cyrenice

Pronounced as Ki-re-nay-is in Zadithi.

One of the oldest cities in Zadith, sometimes called the city of thousand statues: all built from the light coloured stone with a large commercial harbor overlooked by a walled tower. The city’s heart is the central district known as Agora which is the area of markets, public squares and plazas, where the people can formally assemble or gather for festivals, religious temples and shrines and the location of the main municipal buildings. Much smaller artistic and academic districts are also part of Agora. Residential districts are wrapped around the city centre from the north to south east. It looks like there is not much vegetation in the city with most of the gardens being hidden ininternal courtyards.

Cyrenice is known for holding many of the country’s artistic treasures and its vast ancient libraries which are open to the public. Throughout history those libraries attracted many scholars and academics, which allowed Cyrene to contribute to the intellectual life of the Zadithians, mostly through its famous historians, philosophers and mathematicians. One of the city’s attractions is the annual festival when the scholars finally leave the walls of the libraries and their faculties and compete in sports.

Alchemy

The concept of transmutation of base materials into noble metals is not central in Zadithian alchemy - they have plenty of gold without it. Alchemy is not focused on any particular type of science or magic, it is rather broad concept of combining both in various proportions: there are alchemists focused on medicine, physics, mechanics, chemistry, geology and astronomy and so on. Various enhanced crafting like creating magical items for practical use, also sometimes being considered as part of the alchemy.

It is not a new concept is Zadith and there is an ongoing debate on how it originated. Some say that alchemy was developed out of the practical necessity with magicians applying scientific principles to enhance their spells and scientists using magic to achieve faster results, some say it was purely academic discipline which found its practical application.

Much like scientists, alchemists are very proud and protective of their work. They use secret languages and codes to protect their research and notes and some are in the fierce competition with each other.

Alchemy is generally considered to be niche and complex discipline and there are way less alchemists than magicians.

#now the big question is why did I do write all of these#and how do I tag it#the arcana#evpanopolis#the arcana worldbuilding#fan apprentice#worldbuilding#disclaimer: this is intentionally vague and is not supposed to be a representation of any place or culture in the real world

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Art of the Day: Head Effigy Bead

The Moche developed the first state-level political system in the ancient Andes during the Early Intermediate Period (200 BCE-500 CE) in response to wide-ranging events throughout the northern coast. The region's growing populations and occasional droughts of years' duration heightened competition for arable land and precious water. A new elite class, the kuraka, arose to meet the challenges of effective survival by exerting control over coastal resources, from land and water allocations to the human labor needed for such crucial construction projects as large-scale irrigation systems and monumental architecture conveying socio-political and spiritual power. The kuraka also controlled the all-important local and long-distance exchange networks that ensured the availability of both basic commodities and luxury goods. The authority of the kuraka was based on an ideology that claimed their descent from mythic founders. Thus, although the gods were the ultimate source of power, mythical human figures became principal kingpins in the Moche politico-religious schematic. The five major river valleys of the northern coast were united, to varying degrees, under the commanding kuraka socio-political framework. They not only administered all manner of subsistence, social, and religious affairs, but also sponsored the production of prodigious amounts of artworks that denoted high status and underscored the ideological basis of sociopolitical hierarchy Members of the kuraka were adorned with finely crafted jewelry made of silver and gold and often embellished with precious shell and stone inlays. Noblemen buried in the royal tombs of Sipán, an important Moche center, were festooned in all manner of precious metal adornments whose imagery indicated their political office and specified their ceremonial roles during enactments of the Sacrifice Ceremony, which frequently was represented on Moche pottery. This large silver bead may be the head of the so-called Decapitator, a key supernatural being associated with human sacrifice and warrior power. The lord buried in Sipán Tomb 1 was dressed as the Warrior Priest of the Sacrifice Ceremony. He was adorned with jewelry depicting this fearsome being, which thereby connected him to ritual warfare and decapitation sacrifice. Similar gold, copper, and silver effigy bead necklaces bedecked the individuals in Tombs 2 and 3, some beads having the fanged teeth of the deity, whereas others feature humanlike teeth. In this example, the hair, face, and large earflares recall human portrayals, whereas the shape of the mouth, which likely makes reference to the snarl of a feline predator, is more typical of the Decapitator supernatural being. As such, this large silver bead may have alluded to the wearer's spiritual power. Learn more about this object in our art site: http://bit.ly/2N4J9wy

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Increasing Trend of Hyderabadi Professionals Taking Up Farming

Like with the rest of India, farming has historically been one of the major economic activities in Telangana. The region mainly depends on rain-fed water sources for the irrigation system with crops ranging from rice to others like cotton, sugar cane, mango, and tobacco. Recently, crops used for vegetable oil production like sunflower and peanuts, have also gained favour.

Hyderabad its capital, also known as the ‘City of Pearls’ is a place that offers both traditional culture and modernity. It is one of India's fastest growing cities, with rapidly expanding industries and a home to some of the country's most innovative companies. As a major IT hub, it attracts professionals from across the country.

As the city becomes more prosperous and expands in all directions, there has been a growth in the infrastructure of the city, with skyscrapers and new developments being constructed in every direction. This has however come at the cost of green spaces, which have resulted in city residents yearning for them. Moreover, with numerous lakes being filled up and being replaced by physical structures, the city has been facing an increasing flooding problem during the monsoons. Climatic changes and global warming are also making their impact felt.

In recent times, with the proliferation of lifestyle diseases, there has been an Increasing awareness among people about wanting to lead a healthier life, find work life balance, spend time outdoors and on the quality of food consumed. The mushrooming of organic food stores, mandis and healthy food brands are a testament to this.

With the experience of restrictions on movement during the pandemic, people have also wanted to escape city dwellings and move to wider open spaces. There has been a strong need to return to their roots and have green spaces to call their own. This interest has also been inspired by the several farming, gardening and natural food related workshops that have been gaining traction over the last few years.

These have led to several people wanting to own farm plots, farmhouses or buy agricultural land. However, several people wanting to do so are often intimidated by thought of the various steps involved in owning a farm plot – from selecting the right plot to ensuring it has a water and power source, its potential to grow crops, security, maintenance and various other unforeseeable challenges. This thought often drives them away from doing the plunge.

To cater to this rising demand, several agri-asset management companies have come up in the city offering managed farmlands. These managed farmlands vary from dairy farms to organic farming, wood plantations to greenhouses to mix use farm plots.

Besides a personal green space, managed farmlands are also a great option for those who want to build up their wealth and prosperity through agri-businesses and a hedge against other asset classes like equity, debt, gold, and fixed income.

Building long-term wealth with managed farmlands near Hyderabad is a great idea for those looking for a second home near the city. With managed farmlands, you do not have to worry about maintenance or security/surveillance involved after the land acquisition.

The burden of maintenance, safety and security of the farmland is taken up fully, thereby making the farm land always ready for joyful use. This also ensures that the land is insured from any trespass and access by unauthorized persons. This helps customers to do away with the hassle of development, maintenance and security/surveillance involved after the land acquisition.

Suhail Bagdadi is the Marketing & Communications Head of Beforest Lifestyle Solutions. He holds an Advanced Permaculture Design Certificate from Aranya Agricultural Alternatives and runs a 15-acre alphonso mango orchard along the Konkan coast, which he is converting into a food forest.

#managed farmlands near Hyderabad#managed farmlands near Hyderabad for sale#Farming#Farmlands#agriculture

1 note

·

View note

Text

BACK WATER RIPPLES OF KERALA

The Kerala backwaters are a network of brackish lagoons and lakes along to the Arabian Sea coast of Kerala state in southern India (also known as the Malabar Coast), as well as interconnecting canals, rivers, and inlets. The system is labyrinthine and has likened to American bayous. The network consists of five sizable lakes connected by both man-made and natural canals, fed by 38 rivers, and covering over half of Kerala state. The numerous rivers that flowed down from the Western Ghats range created low barrier islands across their mouths, which in turn formed the backwaters. There are several villages and localities scattered across this environment that act as the embarkation and disembarkation places for backwater cruises. In Kerala, there are 34 backwaters. Out of it, 27 situated either parallel to or closer to the Arabian Sea. Inland navigation routes make up the remaining 7.Due to the interaction of freshwater from the rivers and seawater from the Arabian Sea, the backwaters have a special environment. Near Thanneermukkom, a barrage has constructed to protect saline water from the sea from penetrating the interior, preserving the fresh water. This clean water frequently used for irrigation. The backwaters are home to a wide variety of unusual aquatic creatures, including turtles, otters, and mudskippers, as well as terns, kingfishers, darters, and other water birds. Alongside the backwaters, a variety of leafy plants and bushes, palm trees, and pandanus shrubs flourish, giving the area a lush green appearance.The 205 km (127 mi) National Waterway 3 from Kollam to Kottapuram runs nearly parallel to southern Kerala’s coastline, facilitating both cargo movement and backwater tourism. The largest lake, Vembanad, has an area of 2,033 square kilometres (785 sq mi). The Kuttanad region traversed by the lake’s extensive network of canals. Valapattanam is 110 kilometres (68 miles) long, Chaliyar is 169 kilometres (105 miles), Kadalundipuzha is 130 kilometres (81 miles), Bharathappuzha is 209 kilometres (130 miles), Chalakudy is 130 kilometres (81 miles), Periyar is 244 kilometres (152 miles), Pamba is 176 kilometres (109 miles), Achankovil is 128 kilometres (80 miles), Meenachil is 75 kilometres (47 miles), and Kalla (75 mi).The 205 km (127 mi) National Waterway 3 from Kollam to Kottapuram runs nearly parallel to southern Kerala’s coastline, facilitating both cargo movement and backwater tourism. The largest lake, Vembanad, has an area of 2,033 square kilometres (785 sq mi).

One of the main tourist attractions in Kerala are the kettuvallams, or Kerala houseboats, in the backwaters. The backwaters travelled by almost 2000 kettuvallams. The tourist houseboats divided into platinum, gold, and silver categories by the Keralan government.

The rice grown in the lush fields next to the backwaters historically transported using the kettuvallams as grain barges. 100 feet (30 metres) long wooden hulls covered with a thatched covering to provide protection from the weather. The royal family once lived aboard the boats for a period of time. The houseboats have transformed into floating cottages with a sleeping area, western-style bathrooms, an eating area, and a sit-out on the deck in order to welcome tourists. The majority of visitors stay the night on a houseboat.The once-sleepy Ashtamudi Lake has transformed into a bustling tourist destination with opulent resorts lining the lake and its backwaters.In the Indian state of Kerala, the region known as Kuttanadu includes the districts of Alappuzha and Kottayam. It noted for its sizable rice fields and unique geological features. The area one of the few in the world where farming practised between 1.2 and 3.0 metres (4 to 10 feet) below sea level and the lowest altitude in all of India. The Pamba, Meenachil, Achankovil, and Manimala are four of Kerala’s major rivers that enter the area. The state’s top rice grower and a significant location in South India’s ancient history is Kuttanadu. It renowned for its boat races as well.Travelers like Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo praised Kollam (formerly known as Quilon), one of the major commerce hubs of the ancient world. It is also where the backwater waterways begin. About 30% of Kollam covered by the Ashtamudi Kayal, also referred to as the entrance to the backwaters. [6] Kollam city is 28.5 kilometres away from Sasthamcotta Kayal, a sizable freshwater lake.

It is one of Kerala’s freshwater lakes. It situated in Thiruvananthapuram, which serves as the administrative centre for Kerala. The Kovalam beach is closer by.

The state capital of Thiruvananthapuram is around 6 kilometres away from the Thiruvallam backwaters. Thiruvallam, a tourist destination known for its canoe trips, is gaining popularity. At Thiruvallam, the Killi and the Karamana rivers converge. The Veli Lagoon, which is close to Thiruvallam, has a waterfront park, a floating bridge, and amenities for participating in water sports. Another well-liked tourist destination close to Thiruvallam is the Akkulam Boat Club, which provides boating excursions on Akkulam Lake and a kids’ park.Pookode Lake, one of the state’s freshwater lakes, is located in Wayanad. It is also one of Kerala’s seven inland waterways for navigation. The Pookode lake is the source of Panamaram, a torrent that eventually feeds the Kabani River. It has a maximum depth of 6.5 metres and covers an area of 8.5 hectares.In the district of Kannur, tucked away close to Payyannur, is the breathtakingly picturesque backwater getaway of Kavvayi. The largest wetland in north Kerala formed by the Kavvayi Backwaters. The Kavvayi River, along with its five tributaries (Kankol, Vannathichal, Kuppithodu, and Kuniyan), forms the Kavvayi Kayal. The ideal approach to take in the captivating greenery of the surroundings to take a leisurely boat trip in these waterways, which adorned with numerous little islands.Kasargod, a backwater resort in northern Kerala, bordered by the sea to the west, the Western Ghats to the north and east, and noted for its rice farming, coir manufacturing, and beautiful environment. Near Kavvayi Backwater, there are two cruise options: Chandragiri and Valiyaparamba. The old Chandragiri fort is accessible from Chandragiri, which is located 4 km southeast of Kasargod town. A beautiful backwater area can found close to Kasargod. Near Kasargod, there are four rivers that enter the backwaters; along these backwater stretches, there numerous small islands where birds can sighted.Backwaters in Kozhikode, popularly known as Calicut, remain virtually untouched by throngs of tourists. Boaters and cruisers frequently visit Elathur, the Canoly Canal, and the Kallayi River. The Korapuzha Jalotsavam held in this well-liked water sports destination.

Backwaters like Biyyam, Manoor, Veliyankode, and Kodinhi can found in Malappuram’s coastline region. The largest of them is the Biyyam backwater, which is located south of the Bharathappuzha river, which is also Kerala’s second-longest river. Near Puthuponnani Promontary, the Biyyam Backwater and Conolly Canal combine to empty into the Arabian Sea.

Click to know about Google algorithm.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Civilizations from Antiquity we should learn more about

This post is an appreciation to those cultures who are not usually taught at school, or even study at academic levels. It is intended to cause curiosity overall, rather than give many details. What are those civilizations we know little (or anything) about? There are dozens, but here you have only five, as a fresh start.

Urartu (860–590 BCE)

Let’s start with this iron age kingdom. Urartu occupied much of what today is Armenia and part of southern Georgia. For a considerable time, these people were able to confront the great Assyrian Empire, which is a lot to say. After they were finally conquered, it still caused may problems to their rival. We know that a single dynasty ruled the kingdom through its history. The capital city was Tushpa (also, Van). It was a fortress, that assured regional control and defense from the enemies (photo)

According to our sources, Urartu was famous for its metalworks, which were highly appreciated at that time.

Kingdom of Aksum (100– c. 940 CE)

Covering parts of what is now northern Ethiopia and southern and eastern Eritrea, Aksum was deeply involved in the trade network between India and the Mediterranean (Rome, later Byzantium), exporting ivory, tortoiseshell, gold, and emeralds, and importing silk and spices. Aksum remained a strong, though weakened, empire and trading power until the rise of Islam in the 7th century.

We can count many achievements from this culture. They developed their own alphabet (Ge'ez script) which was used to write a vast ecclesiastical literature. Aksum is also famous for the enormous obelisks, used to indicate the presence of underground tombs (see picture). To this day, the Aksumite stelae still stand in the deserts.

Moche (100–700 CE)

This civilization flourished in northern Peru many centuries before the well-know Incas arose. The technical and economic advances surpass those others from the region, and many scholars think that the Inca Empire owes a lot to this previous culture. A highly complex irrigation system, a central religion role in the zone and an amazing development of ceramics, textiles, and metalworks, all that reveals us an extraordinary ability to organize society. By the way, they weren’t an empire or a single state. On the contrary, it is believed that elite culture was formed by many cities that shared a common ideology and religion.

If there is something I must insist on is the quality of their art. Just look at these beautiful gold earrings.

Bosporan Kingdom (438 BCE–c. 370 CE)

This was probably the first “Hellenistic state”, as long as we understand Hellenistic as a mixture of Greek culture and another one (in this case, Scythes). During the 7th and 6th the first Greek colonies were settled in the south of today’s Ukraine, and after some centuries of convivence with the tribes of the steppes, Satyrus (431 – 387 BC) established his rule over the whole region and created a true kingdom. This State survived for a long time, and finally, it became a client state of the Roman Empire, protected by Roman garrisons.

The citizens appear to have lived in a culturally diverse society with free mixing and mingling and cross-fertilization, opposite to the opinion of outposts of Hellenism in a hostile, uncivilized region. Despite this, little is known about this kingdom, situated just in the limits between the classical world and the northern nomads. (Picture: Plaque ‘Head of Medusa Gorgon’)

Chavín culture (900–250 BCE)

Finally, Chavín de Huantar culture. It is not properly a state or any political entity. More probably, we are talking about a number of peoples gathered around a religious center because of a shared ideology. And so, even when its origin is the northern Andean highlands of Peru, it extended its influence on other civilizations along the coast.

Warfare does not seem to have been a significant element in Chavín culture. The archaeological evidence shows a lack of basic defensive structures in Chavín centers, and warriors are not depicted in art. In fact, effective social control may have been exercised by religious pressure, and the ability to exclude dissidents from managed water resources.

Religion was central in Chavín culture, so we found its presence in every single aspect of this civilization, from a sacerdotal elite controlling the whole society to the exclusivity of religious figures in gold-works. (Picture: a gold figure of a condor)

#history#ancient history#ancient civilization#civilization#moche#chavin#bosporan kingdom#aksum#urartu

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Helpful Tips on How to Become a Professional Arborist

Do you like taking care of trees? And do you share the passion too for protecting the environment, and for keeping our forests and nature reserves in tiptop shape? Perhaps you should learn to become an arborist, and at the same time learn the various tree climbing training courses Gold Coast too!

Learn the Applicable Skills & Knowledge

In the Australian setting (and I guess in the overall Commonwealth setting perhaps), arborists are referred to as “tree doctors” who have quite specialized skill set. This allows or enables them to tend and plant trees, as well as examine them for any problems like underlying diseases, nutritional deficits and structural issues.

Now, to be able to do all this, as well as have the ability to maintain different tree species, arborists need to learn certain skills, as well as obtain certain qualifications, to prove that they are indeed competent in this field.

Down Under, an arborist needs a certain qualification to enable them to operate legally. The requirements though vary from state to state, although the first step to certification is by ensuring that you have the relevant education, like the ones included in The Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF), which offers many professional programs on arboricultural training.

The AQF also covers tree climbing training courses Gold Coast which teach the aspiring arborist how to implement biosecurity measures like tree pruning and maintenance, installing irrigation systems, traffic management, aerial rigging, aerial rescue, complex tree climbing, preparing and applying chemicals and power source safety.

Find a Training School or Organization

The next step would be to enhance your career opportunities via practical training. And, the best avenue for this would be to join Registered Training Organizations (RTO) that can help with your certification. And of course, the practical training also includes lectures and hands-on training on various tree climbing training courses Gold Coast.

Register With an Industry Body

Industry bodies or organizations provide budding arborists with a wide array of associated services such as support and training resources, information and programs which ensure that the arborists meet the standards.

A good example of this national industry body would be Arboriculture Australia, which is a national industry body that aims to help arborists through a number of initiatives and programs. Other examples include the Queensland Arboricultural Association Inc. and the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA). And of course, these industry bodies also offer basic and advanced tree climbing training courses Gold Coast , if only to further sharpen your skills as an arborist!

Get Licensed

There's a newly-launched accreditation which recognizes arborists Down Under, and it's the Australian Arborist Industry License. This allows employers to confirm that the individual is a licensed and qualified arborist, which should boost his or her career opportunities.

The tree climbing training courses Gold Coast that are part and parcel of an arborist's training also helps ensure that the individual avoids practices which violates industry standards like using climbing spikes on trees, topping a tree, or removing trees without probable cause.

0 notes

Text

The fight for the Martuwarra

The Martuwarra (Fitzroy) River system winds its way through Western Australia’s Kimberley region, along deep troughs and shallow rivulets, nourishing a complex and finely tuned ecosystem as well as the culture and cosmology of the local traditional owners.

The river is fed by 20 tributaries and flows through three shires across the lands of seven different Indigenous nations, before emptying into the Indian Ocean at King Sound.

For Dr Anne Poelina, a Nyikina Warrwa Indigenous academic and researcher who advocates to protect the river, the Martuwarra is home, and a living ancestor.

“It’s the construction of our whole identity,” Poelina says. “It’s the river of life.”

Last Tuesday, the Western Australian State Government closed the public submission period for decision-making on the Martuwarra’s hydrological future.

The submissions were canvassed in response to the State Government’s November 2020 paper, Managing Water in the Fitzroy River Catchment, that outlined its proposals for the future of the river system. While the proposal ruled out aboveground damming, it advocated taking groundwater from underground aquifers in the system.

Read more: Does nature have rights?

Some have expressed fears that under the auspices of government, and pushed by bastions of industry, the river could go the way of the Murray-Darling Basin, drained of water and lifeblood thanks to overzealous irrigation practices.

The McGowan government finds itself in a balancing act between people who want to preserve the river as it is, and local landholders who demand economic opportunity.

Among the pastoralists and landholders vying for access to the Fitzroy’s aquatic gold is Australia’s richest person, multi-billionaire Gina Rinehart, who wants to divert water from the river for her Liveringa cattle station. Murray-Darling cotton farmers the Harris family are also looking to divert water from the river. [find source]

But the Fitzroy river, like all river systems in the arid, monsoonal Kimberley, is seasonal and unpredictable: in a given year it may flood, filling the entire system, but it also may not. In these in-between times, local species rely on remnant pools to survive until the next flood event, leaving these ecosystems in a precarious balancing act.

In response to the State Government paper, Poelina and the other members of the Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council produced a submission emphasising the importance of foregrounding the Traditional Owners in decision-making, and preventing the extraction of water from culturally and ecologically important tributaries and aquifers. The Council expressed concern about the many unknowns of water extraction in the region and how it may affect local water-flows, including these below-ground aquifers.

“Even at the policy and decision-making processes, we don’t have all of the science to make informed decisions about how we should be taking water from these stressed systems,” Poelina says. “And we don’t appear to be seeing from the state government how they’re going to balance this take against climate science.”

A delicately balanced ecosystem

The Martuwarra is home to several vulnerable and unique species, including the endangered sawfish, one of Western Australia’s iconic species, which relies on wet-season deluges and which is already imperilled by the prospect of more frequent droughts and climate change.

David Morgan is a researcher in aquatic ecosystems at Murdoch University, and a specialist in the unique fish life of the Martuwarra.

“A lot of people think ‘oh, it’s just a river’, but they don’t understand the importance of this river to these globally threatened species,” Morgan says.

Because the Martuwarra is seasonal, the fish in its waterways rely on periodic deluges for their survival.

“There’s only been four years in the last 20 that we’ve had really good recruitment of freshwater sawfish,” Morgan says. “So, we know that the flow is critical, and with reduced flow we know that it can be very drastic.”

Morgan says the fish species that depend on the Martuwarra are already vulnerable to the ravages of climate change, which will push the Kimberley’s already dramatic temperatures upwards.

“When it’s hot, there’s less dissolved oxygen available for fish to access,” he says. “So, you can end up with these massive densities of fish, and then, as we’ve seen in the Murray-Darling, you get lots of fish kills, and that’s going to happen more and more.”

Morgan says that, from his perspective, the extraction of aquifer groundwater is likely to be less risky than surface water extraction – but there are still unknowns.

The below-ground aquifers, some of which are being eyed off for extraction, are also vastly important to the river system in its totality. A 2020 study in Hydrobiologia found that groundwater along the Fitzroy River was intimately related to the biomass and resilience of local benthic algae. Writing online about the research, lead author Ryan Burrows, formerly of Griffith University, warned that reductions in groundwater could influence the productivity of the river and interrupt local food-webs.

Murray-Darling 2.0?

Many of those expressing concerns about developments to the Martuwarra point to the Murray-Darling Basin catastrophe as a lesson in what not to do. Blighted by a cocktail of factors including extreme drought, decades of irrigation and – some argue – poor management practices, the basin no longer has the water required to support itself.

The basin, which produces a third of Australia’s food, has in recent years suffered from mass fish kills, prolonged periods of utter dryness, and the depletion of its ecosystems.

The Australian Government’s Murray-Darling Basin Plan, signed into law in 2012, was designed to establish how much water could be taken from the Basin each year while leaving enough for its local ecosystem. This was meant to be achieved through a system of water rights: the commodification of the Basin’s water into tradeable units that could be regulated. But the plan is controversial, unpopular with agriculturalists who believe they’ve been deprived of the irrigation water they need during droughts, and unpopular with environmentalists who believe it hasn’t done enough to protect and sustain the Basin’s natural flow, which has slowed to a trickle.

Poelina says Traditional Owners from the Martuwarra continue to share their learnings with Traditional Owners from the Murray-Darling about how to protect their waters from going the same way.

“We are learning a lot from the Murray-Darling Basin,” Poelina says. “We are sharing the experience of how these Traditional Owners had this amazing system, resulting in ecocide and incremental genocide with the changes they’ve seen in that system over time.”

Who owns the Martuwarra’s water?

Poelina and the Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council believe a legislative framework is paramount to enable the Traditional Custodians to be involved in river governance, before any allocations or water trading can begin.

“What we’re asking of government is a way that we can have a Fitzroy River management plan that brings everybody to the table, and is grounded in good science and the wellbeing of everything and everyone connected to this globally unique river.”

One of the proposed mechanisms for sharing water with Aboriginal people has been the concept of a Strategic Aboriginal Reserve, a legal framework that allocates a measure of the available water for purchase by Indigenous landholders. But the Council believes there are important conversations to be had about whether water should be a right or a purchasable interest for Aboriginal people.

“A strategic Aboriginal reserve requires Aboriginal people to have a water license, with the capacity and capital to purchase a water license. Aboriginal people will need to partner with someone or have at least several million dollars to be able to do all your studies to apply for a water license to get into the water market, and we think that is definitely unfair and unjust.

“As Indigenous people who have been managing and looking after these systems, particularly the Fitzroy River, since the dawn of time, how come we still have to go through the same processes and have the same level of capital to be able to profit from that water?”

Moreover, she says that allocation of water rights to industry and agriculture should be parked until safe drinking water is available and affordable for Aboriginal communities in the region.

“We have multiple Aboriginal communities in the Kimberley who don’t even have water fit for human consumption,” Poelina says. “So, we’re here fast-tracking and investing in water infrastructure for agriculture when we have not attended to our duty of care to ensure Aboriginal communities have access to clean drinking water.”

Protecting water on a drying continent

Adam Rose is a specialist in water systems and water ecology at Central Queensland University. While his research focuses on the tropical water systems of the Queensland coast, Rose says Australia’s water systems share fundamental similarities that make working with them unique and complex.

“Australia is the driest inhabited continent on Earth,” Rose says. “Years ago, before colonisation, everything was different – the soils were different, we didn’t have hard-hooved animals, and so when it would rain it would soak into the environment and filter through these soils and get to our creeks and rivers.

“All of our plants and animals have evolved under these conditions, and then the white fella arrives and brings these two traditional European farming methods, clearing all of the trees and introducing animals.

“Just in that we changed that water cycle.”

Rose says proper management of our embattled water systems requires relying on traditional knowledge systems, rather than top-down governance.

“I want to know some of the old stories about what plants and what fish were where in the traditional stories,” he says. “Instead of having Canberra tell us what to do, I think we should be joining forces with the traditional owners, getting the farmers and the scientists to actually do the research in that catchment together and start to make local decisions for the catchment.”

Poelina points out that in a warming world, where water tables are shifting south, water governance and management is paramount.

“The Bureau of Meteorology is saying we need to learn to live with less water, and yet the approach (being proposed) is to look at how do we swallow up as much water from the system as possible,” Poelina says. Traditional owners, on the other hand, “live under a law of the river, a law of obligation to protect the river because it is the river of life”.

From her perspective, the Martuwarra has vital importance not just to its traditional custodians but to the nation and the planet, too.

“It’s a national heritage site, and it’s the largest listed Western Australian Aboriginal cultural heritage site, so it belongs to our fellow Australians and it belongs to the world, too. We don’t want a repeat of Juukan Gorge in the destruction of our sacred site.”

The fight for the Martuwarra published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

On soil degradation and the use of non-native plants as weapons to change landscapes and sever cultural relationships to land; and on the dramatically under-reported but massive scale of anthropogenic environmental change wrought by early empires and “civilizations” in the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and ancient world (including the Fertile Crescent, Rome, and early China): I didn’t want to add to an already long post.

This is a Roman mosaic, from when Rome controlled Syria, depicting an elephant (presumably the Asian species, Elephas maximus) interacting with a tiger (the Caspian tiger, a distinct subspecies of tiger, lived in Mesopotamia, the shores of the Black Sea, and Anatolia up until the mid-1900s). This mosaic is striking to me, because I guess you could say that this is clear evidence of the higher biodiversity and more-dynamic ecology of the Fertile Crescent in the recent past, until expanding militarism and empire led to extensive devegetation. After all, does the popular consciousness really associate elephants and tigers with the modern-day eastern Mediterranean and Anatolia? Not really. But for the majority of human existence, lions, tigers, elephants, and cheetah were all living alongside each other in Mesopotamia. Pretty cool.

Anyway, I wanted to respond to this:

Which was in response to a thing I posted:

Pina: Thanks for the addition! I don’t know much about the technicality Rome’s devegetation of the Mediterranean periphery, but - like you - I’ve read some cool articles about it, and then forgotten to bookmark them. (I know that I have at least one good article in print form, about Roman devegetation; I’m going to try to find it.) I’m glad you mentioned it!

The first image is in the public domain and depicts a rhino-shaped ritual wine vessel made of bronze, from about 1100 to 1050 BC, during the Shang era. (The piece is housed at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.) The second image is another bronze wine vessel from a site in Shaanxi Province, this time inlaid with gold and hailing from later in history during the Western Han period, about 205 BC to 10 AD. (Photo by Wikimedia user Babel/Stone.) The rhinos in both of these pieces are depicted with two horns, meaning that they likely depict the Sumatran rhinoceros; this is corroborated by the existence of fossil remains of Sumatran rhinos from across China prior to 1000 AD.

On devegetation in the ancient world:

Yes, it feels like the ecological effects of empires prior to the Middle Ages are not just “under-discussed,” but dramatically overlooked. Some “quintessential and iconic African fauna” like lions and cheetahs lived throughout the Fertile Crescent, until devegetation during the late Bronze Age and, a few centuries later, the ascent of Rome. Caspian tigers (a distinct subspecies of tiger) also lived nearby, in Anatolia, the Caucasus, the shores of the Black Sea, and Persia - right up until the 20th century, in fact! (Other iconic species present on the periphery of ancient Mesopotamia were Asian elephants; leopards are still present.) Aside from the devegetation of the Fertile Crescent and the later landscape modifications of Rome, I also don’t see a lot of popular discussion (there is academic discussion, though, obviously) of ecological change in Zhou-era and early imperial China, either. While early Mesopotamia is famous for the amount of social prestige ascribed to irrigators and engineers, who were evidently essential to maintaining the domesticated crops so important to “hydraulic civilization,” early China (apparently) also revered irrigators and engineers. At least according to folklore and written histories, before the Han period, seasonal floods, especially in the Yangtze watershed, would regularly destroy human settlements. Also, there far more tigers, leopards, rhinos, and elephants present; rhinos and elephants lived as far north as the Yellow River until empire really expanded, and the animals lived as far north as the Yangtze River into the European Renaissance era. So, those people with the technical expertise to “tame the wilderness” by damming rivers or calming floodwaters were given prestige and sometimes treated as folk heroes. [Chinese history is not a subject that I really know a lot about. I’m just relaying the observations made in one of the better books on environmental history in East Asia, which is Mark Elvin’s The Retreat of the Elephants - 2006.]

------

On empires’ use of soil degradation to “sever connections to land” and “indirectly” destroy alternative or resisting cultures:

Seems that empire uses ecological degradation to enact a “severing of relations” (in Zoe Todd’s words). Basically: If you destroy somebody’s gardens, then they have to come to you to buy food. Furthermore, destroying someone’s connection to land will also harm their cultural traditions rooted in that land, eliminating a threat to the imperial cultural hegemony and erasing “alternative possibilities and futures” from the collective imaginary. (And destroying the imagination doesn’t just harm the invaded cultures, it also prevents the relatively privileged people living in the metropole or imperial core from “achieving consciousness” or whatever, wherein someone living in 150 AD Rome or 1890s New York City might imagine an alternative system and potentially dismantle the empire from within.)

It’s violence; destroying soil, cutting forests, it’s violence. But when empires destroy soil, they get to maintain a little bit of plausible deniability: “Ohhh, it’s not like we outright killed anybody, we just accidentally degraded the soil and now you can’t grow your own food. Damn, guess you have to rely on our market now, which also means you have to assimilate/integrate into our culture.”

Europe, the US, and the World Bank did this in West Africa after “independence.” They said “oh, yea, sure, we’ll formally liberate you from colonial rule.” But since the palm and sugar plantations were already installed, and many of the ungulate herds of the savanna had already been killed, what were new West African nations supposed to do? Miraculously resurrect the complex web of microorganism lifeforms in the soil? So what the US and its proxies are essentially doing is saying: “If you want loans, you have to keep the plantations and also install supermarkets to sell Coca-Cola.”

Todd: “The Anthropocene as the extension and enactment of colonial logic systematically erases difference, by way of genocide and forced integration and through projects of climate change that imply the radical transformation of the biosphere. Colonialism, especially settler colonialism – which in the Americas simultaneously employed the twinned processes of dispossession and chattel slavery – was always about changing the land, transforming the earth itself, including the creatures, the plants, the soil composition and the atmosphere.” [Heather Davis and Zoe Todd. “On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene.” ACME An International Journal for Critical Geographies. December 2017.]

-----

On the use of non-native plants as a sort of “biological weapon”:

The use of non-native plants and agriculture to enforce colonization and empire is the whole focus of this influential book from Alfred Crosby. (I have some issues/criticisms of some of his work/theories, but his work is generally interesting.) Crosby popularized the term “neo-Europes,” and he proposes that European empires attempted to subjugate the native ecology of landscapes in Turtle Island, Latin America, Australia, etc., while attempting to introduce European species, cattle ranches, pastures, dairy farms, gardens, etc. in an effort to “recreate” a European landscape.

-----

Speaking of Rome’s devegetation of the Mediterranean: One of the famous cases of Roman devegetation that made the rounds recently was that of silphium. A couple of excerpts:

[From: The Original Seed Pod That May Have Inspired the Heart Shape This historical botanical theory has its roots in ancient contraceptive practices.” Cara Giaimo for Atlas Obscure, 13 February 2017.]

Silphium, which once grew rampant in the ancient Greek city of Cyrene, in North Africa, was likely a type of giant fennel, with crunchy stalks and small clumps of yellow flowers. From its stem and roots, it emitted a pungent sap that Pliny the Elder called “among the most precious gifts presented to us by Nature.”

According to the numismatist T.V. Buttrey, exports of the plant and its resins made Cyrene the richest city on the continent at the time. It was so valuable, in fact, that Cyrenians began printing it on their money. Silver coins from the 6th century B.C. are imprinted with images of the plant’s stalk -- a thick column with flowers on top and leaves sticking out -- and its seed pods, which look pretty familiar:

[End of excerpt.]

Silphium is extinct now. There is a lot of conjecture about what, specifically, caused the extinction. But it looks like the expansion of Rome across the North African coast of the Mediterranean, and Rome’s development leading to soil degradation, is a likely cause.

-----

Thanks @pinabutterjam :3

The scale of ecological imperialism’s effects ... planetary, no escape. It’s exhausting.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

World's driest desert was once transformed into a fertile oasis by bird poop

https://sciencespies.com/humans/worlds-driest-desert-was-once-transformed-into-a-fertile-oasis-by-bird-poop/

World's driest desert was once transformed into a fertile oasis by bird poop

The Atacama Desert has a fearsome reputation. The world’s driest non-polar desert, located along the Pacific coast of northern Chile, constitutes a hyperarid, Mars-like environment – one so extreme that when it rains in this parched place, it can bring death instead of life.

Yet life, even in the Atacama Desert, finds a way. The archaeological record shows that this hyperarid region supported agriculture many hundreds of years ago – crops that somehow thrived to feed the pre-Columbian and pre-Inca peoples who once lived here.

“The transition to agriculture began here around 1000 BCE and eventually supported permanent villages and a sizeable regional population,” a team of researchers, led by bioarchaeologist Francisca Santana-Sagredo from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, writes in a new study.

“How was this development possible, given the extreme environmental conditions?”

Thanks to Santana-Sagredo and her team, we have a solution to the mystery. It was already known that part of the puzzle could have been the use of ancient irrigation techniques, but water availability by itself wouldn’t be the only prerequisite for a successful agricultural system in the Atacama Desert, the researchers say.

Based on previous research by some of the same team – analysing chemical isotopes preserved in human bones and dental remains of pre-Inca peoples – the researchers suspected fertiliser was also used to help the plants grow.

Now, in their new work, there’s fresh evidence to back up the hypothesis.

“We set out to collect and analyse hundreds of archaeological crops and wild fruits from different archaeological sites of the valleys and oases of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile,” Santana-Sagredo and some of her co-authors explain in a perspective article on the research.

In total, 246 ancient plants were analysed – the specimens being conveniently well-preserved by Atacama’s dryness – including maize, chilli pepper, gourd, beans, and quinoa, among others.

(UC Anthropology)

Using radiocarbon dating, and also testing for isotopic composition, the results showed a dramatic increase in nitrogen isotope composition beginning around 1000 CE – a reading so high, in fact, it’s never been seen before in plants, with the exception of certain plants on Antarctic nunataks where seabirds nest.

Amongst the plants tested, maize was the most affected, and at the same time (around 1000 CE), it also became the most widely consumed crop, based on a separate analysis of archaeological human bone and dental remains from the region, which also showed high readings of the nitrogen isotope.

According to the researchers, the “most parsimonious explanation” for the surge in nitrogen values is ancient bird poop – technically known as guano, which has a history of usage as a fertiliser in pre-modern times, including most likely in the Atacama Desert, as a growth enhancer for pre-Inca crops.

While the fertilisation capabilities of seabird guano (aka ‘white gold’) might have taken this ancient culture’s agriculture to a new level, securing the manure wouldn’t have been an easy – nor pleasant – job.

“Before [1000 CE] populations perhaps used other types of local fertilisers such as llama dung, but the introduction of guano, we believe, triggered a considerable intensification of agricultural practices, a step-change that increased production of crops, particularly maize, which rapidly became one of the central foods for human subsistence,” the researchers explain.

“This shift is remarkable also considering the costs in human (and llama) labour involved – guano had to be painstakingly collected at the coast and transported ~100 km [about 60 miles] inland.”

Despite the challenges, the new findings suggest that’s just what Chile’s desert-dwellers did, and historical accounts from centuries later suggest the practice continued well into the era of European contact – it’s just we never had any evidence to suggest the custom began an entire millennium ago.

“Ethnohistorical records from the 16th to 19th centuries describe how local people travelled in small watercraft to obtain guano from rocky islets off the Pacific shore, from southern Peru to the Tarapacá coast in northern Chile, and how seabird guano was extracted, transported inland and applied in small amounts to obtain successful harvests,” the authors write in their paper.

“Although guano was said in early historical accounts to be equitably distributed to each village, the same sources state that access to guano was strictly regulated, warranting the death penalty for those who extracted more than authorised or entered their neighbour’s guano territory, emphasising its high value.”

The findings are reported in Nature Plants.

#Humans

0 notes

Link

Figures dressed in elaborate garments and headdresses process from right to left across the face of one of the pillars of the Temple of the Painted Pillars at the site of Pañamarca in northwest Peru. The figures hold typical Moche objects, including a plate with three purple goblets, a multicolored stirrup-spout bottle, and a feather fan.

The cover of the Autumn 1951 issue of ARCHAEOLOGY features a dramatic scene of close combat between two men, teeth bared, faces bright red with exertion, garments flying, pulling each other’s hair so violently that each grips the ripped-out forelock of his foe. Created by the artist Pedro Azabache, this cover is a replica of a wall painting at the site of Pañamarca on the northwest coast of Peru, done very shortly after the work’s rediscovery. Mural A depicts a contest between Ai-Apaec, the mythological hero worshiped by the Moche culture, which flourished in this region between about A.D. 200 and 900, and his twin or double. Although Pañamarca’s impressive ruins on a granite outcropping in the lower Nepeña River Valley were well known in the first half of the twentieth century, and had been described by travelers in the late nineteenth century, only a few articles about the site had been published and very little had been said about its wall paintings. Thus, when American archaeologist Richard Schaedel arrived there in 1950, he believed that any paintings he might find would be fragmentary at best. Once there, however, he soon found that Pañamarca’s adobe structures had been completely covered in polychrome murals. In a single week—originally planned for five days, the trip was extended when more murals and a group of burials were discovered—Schaedel and his five-person team not only recorded the combat scene, but also discovered new murals of what he identified as a large cat-demon and an anthropomorphic bird. On the walls of a large plaza, they documented a 30-foot-long composition showing a procession of warriors and priests wearing a costume with knife-shaped backflaps known to have been part of Moche sacrificial rituals.

Though in less than pristine condition after more than 1,000 years, the abundance and unexpected state of preservation of Pañamarca’s murals surprised and delighted Schaedel. But it also concerned him. In his article about the site for Archaeology, he writes, “We hope that this description [of the paintings] will serve as a timely note and warning to lovers of art and archaeology in Peru and elsewhere that this rich source of vivid mural decoration, which today only awaits the patience of the archaeologist to reveal, may tomorrow be irrevocably destroyed. If these still unrevealed documents of the human spirit are not to be forever lost to us, we must constantly keep in mind two ideals: as archaeologists, to devote our attention first and foremost to the adequate documentation of fragile paintings; and to create among the public in general an awareness of their aesthetic as well as their documentary value, so that the present apathy towards their preservation may be replaced by a sense of obligation to their protection.”

Over the more than 65 years since Schaedel’s work at Pañamarca, it was widely assumed that his admonitions had been ignored or forgotten, and that the surviving murals had fallen into ruin. Very little fieldwork was conducted after Schaedel’s excavations and work by Duccio Bonavia later in the 1950s, and only a few new paintings were discovered. When archaeologist and art historian Lisa Trever of the University of California, Berkeley, chose to work in Pañamarca in 2010 along with her Peruvian colleagues Jorge Gamboa, Ricardo Toribio, and Ricardo Morales, she wasn’t very hopeful. “I was pessimistic when we began, figuring that most of the murals that had been discovered before had been destroyed, so we set out to map where the paintings had been and to contextualize what remained,” she says. “But when we began to dig, we were shocked that so much had survived from the earlier excavations.” What was even more surprising was that so much more remained in situ, intact, and unexcavated. “We were soon looking at things that no one had seen since A.D. 780, when parts of the site were deliberately buried,” says Trever. “We went in with a sense that Pañamarca was a site of lost monuments and lost masterpieces of the ancient Peruvian past, and were amazed to find out that not everything was lost at all.”

A 1950 photograph taken at Pañamarca shows Mural C shortly after it was exposed by American archaeologist Richard Schaedel. The painting depicts eight figures—likely warriors and priests—standing as much as five feet tall.

The name “Moche” or “Mochica” comes not from any ancient source, but was given to the culture in the 1930s because the region’s ancient center was located near the modern town of Moche. Rather than being a single political entity or state, the Moche culture was a loose system of chiefdoms situated in multiple irrigated valleys, linked by shared practices and common beliefs. Their territory encompassed more than 400 miles along the coast of northern Peru. While not exactly a political capital, the cultural and artistic homeland of the Moche world was located in the Chicama and Moche Valleys, near the city of Trujillo. At some point, Pañamarca, which was about 100 miles to the south, grew in religious and cultural importance.

The Moche were skilled builders and artists. At some sites they demonstrated this by undertaking large construction projects. Other locations were peopled with accomplished metalsmiths or expert ceramicists, and still others boasted gifted mural painters. “There is an interesting view developing among scholars about a world of different accomplishments in different places that breaks down the monolithic view of Moche culture,” says Trever. Moche potters created evocative ceramics depicting daily life, the natural world, religious sacrifices, and deformed and even skeletal figures, as well as an extraordinary panoply of hybrid monsters, mythological creatures, and gods in many forms. Gold and silver earspools, necklaces, and rings, some of which are inlaid with semiprecious stones, have been found at many Moche sites. Early Moche artists sculpted clay bas reliefs and covered them with mineral-based pigments at sacred locations such as Huacas de Moche, with its highly decorated Huaca de la Luna, and at with its parade of naked captives and intricate geometric patterns. Later, they abandoned the relief style and replaced it with the flat narratives that cover the smooth adobe walls of their temples and public buildings. These paintings reveal much not only about the Moche in general, but also about how Moche rulers chose particular ways of expressing their local identity in a world where heterogeneity reigned.

A newly excavated figure (left) and a watercolor of the figure (right) at Pañamarca show one of a pair of supernatural combatants. The second figure is likely hidden behind the adobe bricks visible at the left of the image.

According to the German linguist Ernst Middendorf, who visited the ruins of Pañamarca in 1886, the Quechua name for the site, “Panamarquilla,” means “little fortress on the right bank of the river.” Trever, however, suggests a different, and more evocative, reading of the name: “little fortress of the paintings.” Pañamarca’s artists were deeply invested in painting, and the murals that cover their monumental temples, including the Temple of the Painted Pillars, reference a Moche ideology focused on either supernatural beings engaging in mythological acts or on human beings performing ritual acts, explains Trever. But adobe is ultimately not permanent—it is eroded and damaged by rain, wind, and time in a way that stone is not. “Because they are building fast, they are constantly remaking their built environment. This gives an immediate sense of their ongoing engagement with the living world,” says Trever. “And because Moche architecture, like Mesoamerican architecture, is renovated and not knocked down, what you end up with is like a set of architectural nesting dolls or onion skins.”

Furthermore, at Pañamarca, Trever sees a localized expression of identity reflected in the murals that is very different from what can be seen at other Moche sites. She believes there was an anxiety about being in the hinterland, 100 miles from the Moche epicenter, that may have led to an increased sense of orthodoxy in the imagery. “What is striking here is that we don’t see a hybrid form of Moche at all, but an even more conservative, even more explicit, Moche ideology expressed,” she says. “It’s almost like they have doubled down on the canon because they are in a more remote location intermingling with peoples of other cultures who aren’t like them.”

The Mural of the Fish adorns one of the walls of a ceremonial platform at Pañamarca. The sea creatures depicted include (clockwise from left) a ray painted using blue-gray paint over red pigment, a long red, white and blue fish, and a small red fish with blue fins.