#IV CIAM

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Das novas funções urbanas (e humanas)

Talvez a pandemia de covid-19 tenha colocado em definitiva obsolescência a Carta de Atenas ao deslocar os eixos principais da discussão sobre as funções humanas da cidade. Isso ocorre principalmente por adentrarmos em um novo período histórico no qual a discussão das localizações deixa de ser uma questão primordial de desenho urbano e passa a ganhar relevâncias de outras naturezas. Resultado do…

View On WordPress

#análise#arquiteto e urbanista#arquitetura e urbanismo#Carta de Atenas#CIAM#conceito#covid#desenho#desenho urbano#desenho urbano modernista#história#IV CIAM#Le Corbusier#pandemia#planejamento#planejamento urbano#projetos#questionamento de modelo urbano covid#questionamento urbano#Ricardo Trevisan#urban design#urban planning#urbanismo#urbano

0 notes

Link

The Fourth Congress of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM IV) in 1933 stands as a milestone in the history of modern architecture and urbanism. It was the culmination of a long process of discussions and debates among well-known modernist architects as to the position of architecture in regards to social housing, urban planning, and economic development. Far from being a simple academic or technical matter, the course and the aftermath of the Congress revealed that a series of crucial political and theoretical implications lay at the core of these debates, while bringing to light divergences within the modernist current, namely in relation to critiques of capitalism and fascism, the issue of socialism, or the vanguard role of the architect. As pointed out by Kenneth Frampton (1980), the Fourth Congress marked the rise to dominance of Swiss-French Le Corbusier. Whereas the first phase of the Congresses (1928-1933) was dominated by the German socialist tendency and the Neue Sachlichkeit, the second phase of the CIAM (1933-1947) signalled a less militant and critical urbanist model, under the influence of Le Corbusier and the French approach, which would reach its full potential in the third and last (“liberal idealist”) phase of the CIAM series, after 1947 (Frampton 1980). Interestingly, and not by chance, the 1933 Congress took place on the cruise ship “Patris II” that travelled from Marseilles to Athens and back, between 29 July - 14 August 1933. It was the first of a series of Congresses that were organised in a rather “theatric” or romantic atmosphere, away from the urban reality of typical industrial settings (Frampton 1980). The working sessions took place on the outward leg of the voyage (29-1 August), in Athens (2-4 August), and the return leg (10-13 August), with a closing session in Marseilles (14 August) (Gold 1998). The Congress has further been associated with Athens due to the fact that in later years, Le Corbusier published his own loose rendering of the Congress workings under the title La Charte d’Athènes (The Athens Charter, 1943), a very influential though strongly criticised text on urban planning.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

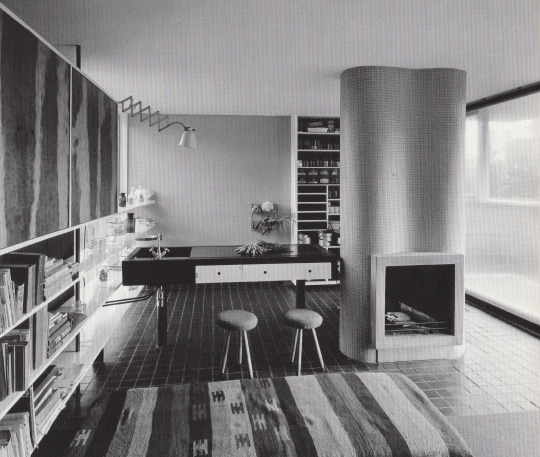

Charlotte Perriand

https://www.unadonnalgiorno.it/charlotte-perriand/

Charlotte Perriand, architetta e designer francese è stata una figura fondamentale della storia del moderno design. Ha creato pezzi iconici tuttora in produzione.

Nonostante abbia avuto una lunga e articolata carriera, troppo spesso viene ricordata soltanto per la sua fortunata collaborazione con Le Corbusier e Pierre Jeanneret, a cui a lungo sono stati attribuiti pezzi d’arredo concepiti invece da lei.

Si è occupata di design di mobili, arredo e architettura di interni, influenzando anche le forme architettoniche costruite.

Charlotte Perriand nacque a Parigi il 24 ottobre 1903, si è diplomata nel 1925 all’École de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs e, nello stesso anno, ha presentato una collezione di oggetti e arredi all’Esposizione parigina di Arti Decorative.

Dal 1927 al 1937, in maniera continuativa, ha lavorato nello studio di Le Corbusier realizzando mobili entrati nella storia del design e condividendo la visione dell’arredo come parte di un sistema che sfrutta le grandi potenzialità di nuovi materiali e tecniche di lavorazione e produzione in serie.

Uscita dal famoso atelier, ha continuato il suo sodalizio con Pierre Jeanneret e l’architetto giapponese Junzo Sakakura, mantenendo viva l’etica dello studio (l’interesse per il lavoro di gruppo e per l’integrazione tra architettura e progetto degli spazi interni).

Affascinata dalla cultura industriale, utilizzava i nuovi materiali (acciaio, alluminio, vetro) per forme e prodotti messi al servizio del miglioramento della vita quotidiana.

Nel 1929 è stata co-fondatrice dell’U.A.M. (Union des Artistes Modernes) e nel 1933 è stata una delle rare donne al IV Congresso del CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) di Atene.

Ha svolto un ruolo da protagonista nel movimento di rinnovamento dell’architettura e della cultura del secolo scorso.

Ad arricchire e ispirare la sua grande creatività furono sicuramente anche le importanti esperienze in giro per il mondo.

Ha lavorato in Unione Sovietica, in Giappone, in Vietnam, in Brasile, vantando prestigiose collaborazioni con commesse private e pubbliche, compresi gli uffici di Air France nel mondo, le residenze diplomatiche franco-nipponiche, e la riprogettazione degli interni del Palazzo delle Nazioni Unite a Ginevra nel 1961.

È stata sempre affascinata dall’Oriente e dal Giappone, in particolare, dove rimase per tutto il periodo della Seconda Guerra Mondiale, perché impossibilitata a rientrare in patria, e di cui studiò tradizioni e materiali adattandoli a vari pezzi di design suoi e di altri. Tenne varie esposizioni nell’impero del Sol Levante e, nel 1942, scrisse anche il libro Contatto con il Giappone.Vi fece ritorno più volte, creando occasioni di incontro e di scambio, scrivendo e traducendo una parte dello spirito giapponese nel proprio modo di progettare e interpretare le cose del mondo.Cinquanta anni più tardi, nel 1993, ebbe anche l’occasione di realizzare una Casa del Tè all’interno del Festival Culturale del Giappone organizzato a Parigi dall’UNESCO per sviluppare il dialogo tra culture al fine di creare un luogo universale di scambio. Un invito a celebrare il rito dell’ospitalità, il piacere della creatività, la ricchezza del dialogo multiculturale. Tra le numerose opere di design e di architettura di Charlotte Perriand si ricorda anche la stazione sciistica Les Arcs in Alta Savoia (1967-1982), che la vide coordinatrice di un team composto da architetti, ingegneri e urbanisti. Il progetto nacque con l’inetnto di offrire in tempi brevi e a costi accettabili strutture adeguate per il tempo libero e lo sport di massa. Un omaggio ben riuscito all’altra sua grande passione, la montagna.

Charlotte

Perriand

è stata una professionista che è riuscita a emanciparsi in un ambiente quasi esclusivamente maschile, come ha raccontato nella sua autobiografia

Io Charlotte, tra Le Corbusier, Léger e Jeanneret

del 1998.Le sue scelte e il suo stile di vita andarono di pari passo con la sua pratica progettuale, capelli tagliati a zero, gioielli fatti con cuscinetti a sfera così come l’investimento personale nello sport e nei viaggi. Nell’ultima parte della vita rallentò l’attività ma mantenne sempre aperto il suo atelier. Ha Ricevuto numerose onorificenze e le sono state dedicate diverse mostre retrospettive.Si è spenta a Parigi il 27 ottobre 1999.

Responsabile dell’archivio di Charlotte Perriand a Parigi è oggi Pernette Perriand, sua figlia che per più di 20 anni le ha fatto da assistente.

1 note

·

View note

Text

FOMA 9: Radical Open Architecture

Our ninth edition of Forgotten Masterpieces focuses on two Dutch architects from the period between 1950’s until the 1970’s, Herman Haan and Frank van Klingeren, which are relatively unknown outside the Netherlands. Although they differ in their architecture, what connects them is their position towards an open society, which was – sometimes quite literally – realized in their work. Besides that, they were both media (television mainly) personalities in an era when this was not common among architects.

Materiality of the Haan’s House. | Photo by Violette Cornelius

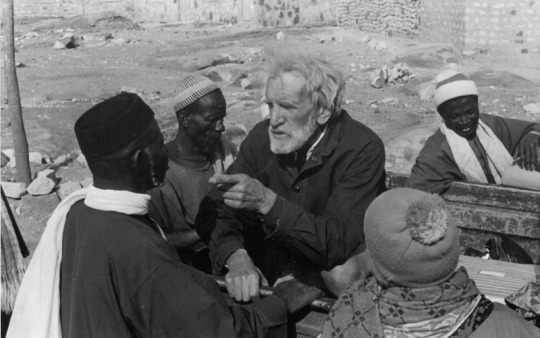

Herman Haan (1914-1996), a typical architect’s architect, was admired among colleagues, but hardly known by the general public. In his case it must be noted that he was very well-known in the 1960’s outside the profession because of the media attention (television, newspapers, books) he received for his travels and explorations in and around the Sahara and Mali. In Mali he documented the life and artefacts of the Dogon people and he was leader and initiator of an expedition that discovered the remains of the forefathers of the Dogon: the Tellem people. In fact, he had travelled to Africa on a yearly basis (mainly in and around the Sahara) since he was a young boy, and one could say that he lived two full lives; one of an adventurer/ explorer/ archaeologist and another life as an architect in the Netherlands. He was a sort of an architect Indiana Jones.

Herman Haan among the Dogon. | Source via Partners Pays-Dogon

As an architect he was one of the incidental participants of the Team 10 family and he brought Aldo van Eyck into contact with the Dogon people. He was also one of the Team 10 members that attended the famous CIAM meeting in Otterlo (NL) in 1959, that caused CIAM to break up definitely. His work consists mainly of private houses. It is very much within the post-war, modernist tradition of Team 10, but with a special open brutality and a humanist twist. He was one of the first modern architects that re-used building materials in his designs.

Herman Haan’s house in Rotterdam, 1951-53. | Photo by Violette Cornelius

Haan build the radically open house for himself and his wife Hansje on a piece of land at the edge of Rotterdam, where the debris of the demolished city centre during a bombardment in 1940 was collected. It consists of two elongated volumes: an elevated, floating open volume with the living room above and a small architect’s studio underneath half of this volume, and a second, closed volume with garage and two small bedrooms. In-between is a double height open space that connects both volumes as an entrance lobby.

The main feature of the living room volume is the set of four glass sliding doors, that can all be opened at the same time, thus literally opening the living room to the outdoors and the view over one of the main entrance roads of the city (and Haan did not believe in the use of curtains either). Another feature is the open kitchen, if not one of the first in architecture, then certainly of one the most radical open kitchens ever. It consists of a simple, small cooking table with a floating kitchen sink that stands in the middle of the living room and is connected to the open fire chimney only. Cooking is a social activity, so Haan had learned in Africa.

Open space and open kitchen. | Photo by Violette Cornelius

The bricks of the closed bedroom volume used in the interior are re-used pavement bricks from the quays of the Rotterdam harbor. An old poplar tree that stood on the site was cut into veneer and used as a finishing layer of cupboards all around the house. Parts of the stone flooring was salvaged from the rubble heap on which the house is build. The house is still standing, but the radical openness proved to be too much for the current owners. It is today surrounded by a wall of conifers, and parts of the glass facades are closed off.

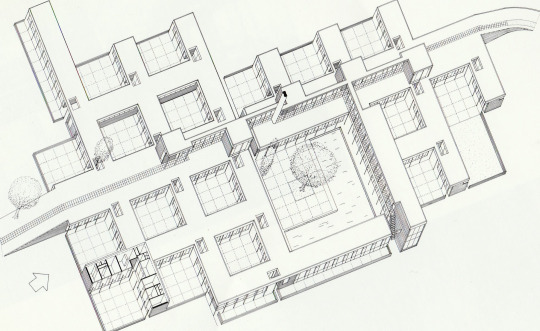

Patio Student Housing, Drienerlo Enschede, 1964-65. | Source Rijksdient voor het Cultureel Erfgoed

Herman Haan was asked by his mentor Willem Van Tijen (a first generation functionalist modernist) to build a batch of student housing for the campus of a new technical university in Enschede. It is unquestionably his most African project. The concept was based on the Matmata cave dwellings of southern Tunesia, famous for being the home of Luke Skywalker in Star Wars IV. It is also his most structuralist design, a so called mat-building based on a continuous square configuration, that was also one of the Team 10 tropes. The design consists of seventeen square units, joined in a larger configuration. Each unit consists of a patio with student rooms on two sides. Eight students live in such a patio unit (six one-person rooms, one two-person). Access to the rooms is from the patio, so each student room has his own front-door. Access to these patio’s themselves is mainly from the roof of the one - storey complex. A foot-path and bicycle road crosses the roof of the complex. The roof itself was one of the first green roofs in the Netherlands, sowed in with grasses. In the middle of the complex a larger central square and pool serves as a meeting place for the student community. The same pavement bricks from the quays of Rotterdam harbor, that he used in his own house and other projects, were used extensively in this one too. The project was recently fully restored and established as a National Monument of post-war architecture.

Frank van Klingeren selling his open architecture. | Source via Nieuwlanderfgoed

Frank van Klingeren (1919-1999), a Provo in a business suit was, unlike Herman Haan, a real outsider in the Dutch architecture scene of the 1960’s and 1970’s. Trained as a construction engineer, he was a self-taught architect that kept away from architecture gatherings or cliques. He was more at home among people from avant-garde theatre of the period, than among ‘Forum’ architects like Van Eyck, Bakema and Hertzberger, although he shared a lot of his ideas with the latter. They even received the Fritz-Schumacher-Preis in 1974 together, Hertzberger for his Centraal Beheer office in Apeldoorn, and Van Klingeren for ‘t Karregat in Eindhoven. Both buildings celebrating multi-functionality and an openness towards change.

Although Van Klingeren was quite productive as an architect from the late ‘50’s to the mid ‘70’s, his main claim to fame was established with the design of three consecutive multi-cultural community buildings or Agora as he called them; De Meerpaal in Dronten, Agora in Lelystad and ‘t Karregat in Eindhoven. But his media presence was broader than that. Especially after finishing De Meerpaal, he evolved towards a counterculture societal critic and television personality, while keeping his distance from direct involvement in flower power, hippie or provo movements. He was in that sense a Provo(cateur) in a business suit.

De Meerpaal, Dronten, 1965-1967 | Photo by Jan Versnel

Asked for a simple multipurpose community building with provisions for amateur theatre and music, sports and a small café for new inhabitants of the pioneer-village Dronten that was being built in the new polder Flevoland, Van Klingeren did much more than that, and in a sense also much less. He gave more space, more functionalities and more possibilities, but less stuff (walls, floors) and in a way less architecture. Van Klingeren was inspired by the village squares or agora of the Mediterranean that functioned as meeting places, open-air theaters and playground, while showing a generic, in fact absent, architecture. In this sense his agora can be seen as a sort of architectural urbanism.

De Meerpaal is in fact nothing more than a covered village square, protected from the northern climate by glass walls. It is a large glass-and-steel box measuring 50x70 meters with a couple of smaller brick boxes (some art and exhibition rooms, a tilted box with restaurant/ café, and a small staff office) added along the edges. In the middle of the covered space an oval open-air theatre - soon dubbed ‘The Egg’ - is the main architectural gesture. There are hardly any walls inside, neither are there many spaces for any specific function. All functions mix, sometimes causing hindrance. According to Van Klingeren, hindrance leads to conversation and mutual understanding. De Meerpaal was used for many different functions; the weekly market, agricultural exhibitions, sports, parties, large scale meetings etcetera. The oval theatre with its central stage (the setting of audience and use could be changed easily, anything was possible except a traditional proscenium set-up), became a place where alternative theatre groups loved to perform.

De Meerpaal was also the main stage for large size, live national television productions and games, until large-scale studios were built in Hilversum. Besides this television attention for Dronten, it was also equipped with a (rotating) film screen on which, besides normal movies, live television could be screened of the so-called Eidophor technique. Thus, the whole village could watch the news or football matches together from the indoor terrace of the café. De Meerpaal has, with some merit, been compared to Cedric Prices (unbuild) Fun Factory of the same time. But while Fun Factory can be called a machine for multi functionality, full of specific intentionality, De Meerpaal is more like a generic square where the intentionality of use and meeting is not outspoken, but nevertheless - maybe more so than in Fun Factory - more open to chance and unpredictable uses.

Agora Lelystad, 1966-1972 | Photo by Jan Versnel

While construction work for De Meerpaal was still going on, Van Klingeren was commissioned to design a similar multifunctional building for Lelystad, the second new town to be built in Flevoland. It was planned to become the largest city and capital of the new polder province. The first design elaborated further on the open concept and mix of functions of De Meerpaal. In this case the scale was larger and Van Klingeren managed to lure in the churches (three different denominations) into the collective. Although each church would have its own space, it was to be open like the open-air theatre and - as Van Klingeren argued - since these spaces would only be used on Sundays, they could double as extra theatre and meeting spaces for the rest of the week.

Meanwhile it was decided that not Lelystad but a newer town Almere to be built closer to Amsterdam would be more important and bigger, and construction of Lelystad was delayed. This meant that the scale and budget of Van Klingeren’s Lelystad Agora diminished too. Instead Van Klingeren proposed the opposite; to enlarge the program with shops and housing facilities (hotel, boarding house), but to do this within the limited budget (to do more with less, was one of his favorite slogans). He proposed a U-shaped steel post-and-beam structure of three storeys, to be left open and to be colonized over time by the people and by entrepreneurs. The ground floor would still be like De Meerpaal, only a swimming pool was added. This open ground floor would be connected to the adjoining park so that Van Klingeren started to title the different zones in the lay-out as if they were landscapes: theatre landscape, youth-cave, swimming and undressing landscape. All in an open ‘wall-less’ setting. While De Meerpaal could be called urbanism (realised with architectural means), this last design for Lelystad would have been a landscape design instead, growing over time. The proposal proved to be too radical for Lelystad and a toned down. Conventional Agora was built in the city centre by one of Van Klingeren former employees.

‘t Karregat Eindhoven, 1970-1973 | Photo by Jan Versnel

Van Klingerens attention had already shifted towards Eindhoven. There he was given the opportunity to build another multifunctional community building for a new experimental housing project. This time it would include – besides the cultural and sports facilities – a small shopping mall (bakery, greengrocer, a small supermarket) and a health facility with general practice (the café serving as a waiting room) and a pharmacy. But the real experiment was the inclusion of two elementary schools and a nursery school. These too would be built without any internal walls to speak of, one organic whole with the rest of the spaces and facilities, a field of communal activity. Children, according to Van Klingeren, would learn their arithmetic next to the supermarket cash desk, mothers could meet each other at the café bar after bringing their kids to school.

The one storey building (or rather the enclosed and climate controlled landscape) is situated underneath a flat roof with an open steel structure, that is supported by steel umbrellas; pyramid shaped skylights on open steel columns. All services (air-conditioning, electricity, rainwater drainage and ventilation) are positioned in sight within the steel roof structure, and can be accessed (and changed when the floor configuration is changed) from below. The perimeter facade is built-up out of off-the-rack components (mainly from the glass-house industry). In general, there is a certain high-tech feel to the architecture, albeit with the informal sloppiness of a self-built community house. Named ‘t Karregat (cart-sink after the shopping carts that would gather there) it was opened in 1973 without hardly any change in the original concept. After a couple of years, the schools without walls proved to be too much for the teachers, that went into the experiment without any primary experience whatsoever in new schooling methods. Glass partitions were applied, but besides that the openness was maintained and ‘t Karregat became an overnight success, also because the community ran the cultural facilities for themselves.

Afterlife

Both De Meerpaal and ‘t Karregat were highly successful until the 1990’s. When De Meerpaal, formerly publicly owned, was privatized in the 1980’s the open space was divided into smaller areas, and finally plans were made to demolish it around the year 2000. Protests from the architecture community and the State Architect managed to save the structure, especially the roof and The Egg. But several theatre spaces and a public library (all very much enclosed) were added so that the new Meerpaal can hardly be called open anymore, at least not in the sense that it was open in the 1960’s, both architecturally and functionally. More or less the same fate came over ‘t Karregat. After a successful period of a couple of decades, plans for demolishment were halted, and it is now restored; but a smooth false ceiling has killed the informal sloppiness of the original, partition walls have been added, patios are cut into the roof. Operation succeeded, patient died.

One may wonder whether this open architecture of De Meerpaal and ‘t Karregat was not so much geared towards it’s own time, and so much part of the open society, that it failed to be open towards societal change in the 1990’s. It very well may be the case, but then so is the architecture of the renewal. One of the protesting architects against demolishing De Meerpaal, Kas Oosterhuis, proposed to wrap the building up in plastic and to wait until society and technology would have been advanced towards a new phase fitting the original intentions of De Meerpaal. This would actually have been a great solution, and one has the feeling that now, only fifteen years after, the new Meerpaal feels old, and the old Meerpaal would fit much better in our current times, which are media driven, semi-virtual, but also with a longing for the open society of 50 years ago. The plastic could have been wrapped of already.

---

#FOMA 9: Piet Vollaard

Piet Vollaard is an architect and architectural critic working in Rotterdam. Besides monographs on both featured architects; ‘Herman Haan, architect’, Rotterdam (1995) and ‘Hinder en ontklonteren, architectuur en maatschappij in het werk van Frank van Klingeren’ with Marina van den Bergen, Rotterdam (2003), his publications include several Architectural guides to the Netherlands with Paul Groenendijk, Smart Architecture with Jacques Vink and Ed van Hinte, Rotterdam (2003); Positions, six Dutch architecture photographers with Simon Franke and Allard Jolles, Rotterdam (2010); Making Urban Nature with Jacques Vink and Niels de Zwarte, Rotterdam (2017), on nature-inclusive design in an urban context. He was founder and editor in chief of ArchiNed (1996-2013), and visiting teacher at several architecture schools in the Netherlands. His current activities focus on urban nature in a designer and ecologists collective The Natural City, and Stad in de Maak / City in the Making a collective of architects, designers and artists working in the field of commoning and activating empty buildings and related urban activism.

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carta de Ateneas. CIAM Congreso internacional de arquitectura moderna. 1933

A. Generalidades.

1. La ciudad es un conjunto económico, social y político, que construye la región.

2. Yuxtapuesto, valores de orden psicológico y fisiológico, individuales y colectivos.

3. Influencia en el medio por constantes psicológicas y biológicas.

4. Geografía y topografía.

5. Recursos de la región.

6. Sistema administrativo

7. Circunstancias particulares históricas.

8. El desarrollo de la ciudad tiene cambios continuos.

B. Estado crítico actual de las ciudades.

I Habitación/Hay que exigir

10. Población densa.

11. Falta de espacio, superficies verdes, y manutención en edificios.

12. Desorden de higiene.

14 y 15. Mala distribución de zonas

17. Largas vías de comunicación, perjudican.

18. Mala orientación.

20. Escuelas lejanas y mal sitiadas.

21. Barrios suburbanos.

24. Mejor topografía, asoleamiento y áreas verdes. }

26. Razonar en base a la naturaleza del terreno.

29. Recursos técnicos modernos para construir

II Esparcimiento/ Hay que exigir

31. Áreas libre suficientes.

36. Todo barrio habitacional debe contar con áreas verdes necesarias para el desarrollo racional.

39. Horas libres semanales se pasen en lugares favorablemente preparados

III Trabajo/ Hay que exigir

41. Sitios de trabajo fuera del conjunto urbano

42. Dejar de normalizar la ligación entre la habitación y trabajo

46. Reducir al mínimo las distancias de trabajo y habitación.

IV Circulación/ Hay que exigir

51. Red actual de vías antigua.

52. En la actualidad ya no responden correctamente las vías.

53. Dimensionamiento de vías.

59. Análisis útil de los nuevos parámetros.

60. Clasificación de vías de circulación.

62. Relación peatón, automóvil.

63. Calles diferenciadas según su destino.

V Patrimonio histórico de las ciudades.

65. Valores arquitectónicos conservados.

66. Conservar siendo de cultura anterior o de interés general.

68. Presencia perjudicial remediada con medidas radicales.

69. Crear áreas verdes.

C. Puntos de doctrina

77. Las bases del urbanismo son cuatro funciones: habitar, Trabajar, Recrearse y circular.

79. El ciclo de funciones cotidianas será reglamentado por el urbanismo

82. El urbanismo es una ciencia de tres dimensiones.

87. Para el arquitecto, la escala será la humana.

90. Utilizar recursos de técnica moderna.

0 notes

Text

Projekty urbanistyczne i architektoniczne Oskara Hansena realizowane w latach 1948–1981

1948 - Osiedle Dębiec pod Poznaniem.

1948/1949 - Aluminiowe wille: osiedle w Ville Neuve St. Georges we Francji w pracowni Pierre'a Jeannereta.

1949 - Projekt osiedla dla 5 tys. mieszkańców International Summer School of Architecture, CIAM, Londyn (jedna lokata w dziale mieszkalnictwa).

1951 - Udział w konkursie na odbudowę Cedergrenu (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

1951/1952 - Projekt wnętrza na torach wyścigowych na Służewcu w Warszawie (współautor: Jerzy Sołtan).

1952 - Projekt wnętrza tymczasowego ratusza w Warszawie, w dawnym kinie „Świat” (współautor: Lechosław Rosiński).

1954 - Inwalidzki Kiosk Ruchu.

1955

Wnętrza własnego mieszkania w Warszawie (współautor: Zofia Hansen),

Projekt pawilonu o powłoce wypełnionej gazem lotnym na Międzynarodowe Targi w Izmirze (Turcja).

1955/1956 - Pawilon Polski, Międzynarodowe Targi, Izmir, (współautor: Lech Tomaszewski).

1956 - Stoisko wydawnictw lekarskich na Targach Książki w Warszawie.

1957 - Projekt stoiska wydawnictwa „Arkady”, Warszawa.

1958

– Osiedle Rakowiec dla WSM – budynek 12, 13 (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

– projekt konkursowy pawilonu polskiego na EXPO 58 w Brukseli (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Zofia Antosik, Witold Janowski, Jan Kosiński, Jan Meissner, Lechosław Rosiński).

– projekt konkursowy centrum kulturalnego w Montevideo (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Lech Tomaszewski).

– projekt rozbudowy gmachu wystawowego CBWA Zachęta w Warszawie (współautorzy: Lech Tomaszewski, Stanisław Zamecznik).

– projekt pawilonu na Festiwal Muzyki Współczesnej w Warszawie (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

1959

– Centrum handlowe, Pułtusk, (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

– Pawilon Polski, Międzynarodowe Targi, Sao Paulo, (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Lech Tomaszewski).

1960 - Studio Eksperymentalne Polskiego Radia (muzyka elektroakustyczna), Warszawa (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Jerzy Dowgiałło, Zbigniew Lebecki, Krzysztof Szlifirski, Józef Patkowski, Edmund Jaroszewicz, Witold Straszewicz).

1961 - Osiedle Lubelskiej Spółdzielni Mieszkaniowej im. J. Słowackiego (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Jerzy Dowigałło oraz zespół).

1962

– Teatr Formy Otwartej w plenerze, Lublin, (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Marek Konieczny).

– Osiedle Energetyka, Torwar, Warszawa, (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, współpraca: Bohdan Ufnalewski).

1963

– Projekt 24-kondygnacyjnego budynku dla osiedla Torwar (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

– Osiedle Przyczółek Grochowski dla Spółdzielni Młodych, Warszawa, (współautor: Zofia Hansen, współpraca: Marek Konieczny).

– Studium Pedagogiczne, Lublin, (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Jacek Wolski, współpraca: Marek Konieczny).

– Opracowanie plastyczne stopnia wodnego, Dębe pod Warszawą, (współautor: Emil Cieślar).

1964 - Projekt zagospodarowania Ogrodu Botanicznego dla Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

1965–1966 - Kolorystyka i centrum handlowe dla osiedla im. J. Słowackiego LSM w Lublinie oraz projekt drugiej części osiedla (współautorzy: Zofia Hansen, Jerzy Dowigałło oraz zespół).

1966

– opracowania modelowe Linearnego Systemu Ciągłego i jego I konkretyzacja (współautor: Zofia Hansen, współpraca: Marek Konieczny, T. Kujawa, G. Marczak, H. Rzenca).

– Projekt Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, Skopje, Jugosławia, (współautorzy: Sveln Hatloy, Barbara Cybulska, Lars Fasting).

1967 - Projekt centrum handlowego dla osiedla Przyczółek Grochowski w Warszawie (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

1968

– Własny dom na wsi, Szumin, (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

– II projekt konkretyzacji LSC dla 16 tys. mieszkańców Warszawy: Ursynów – Lasy Kabackie, tzw. fragment Pasma Mazowieckiego (współpraca: Jerzy Dowigałło, Witold Chróścicki, Arwid Hansen, Grzegorz Kowalski, Bohdan Urbanowicz, Stanisław Zych, Henryk Jurkowski, Tadeusz Michalak, Teresa Pietkiewicz, J. Sibiga).

1969 - III projekt konkretyzacji LSC i projekt osiedla mieszkaniowego dla terenów sejsmicznych w Limie (Peru) wykonany na zlecenie ONZ, w ramach międzynarodowego konkursu na projekty taniego budownictwa, częściowo zrealizowany, (współautor: Svein Hatloy, współpraca: Jerzy Dowigałło, Józef Kozierski, Jan Goots, Grzegorz Kowalski).

1970 - Projekty „Światowit” i „Autoteatr”, Sympozjum Plastyczne, Wrocław '70.

1971 - Projekt zagospodarowania starego koryta rzeki Warty (współpraca: Jan Berdyszak, Jerzy Buszkiewicz, Ryszard Semka, Magdalena Więcek).

1972

– Opracowanie prognostyczne zagospodarowania kraju w oparciu o LSC (współautor: Svein Hatloy).

– Projekt modernizacji Teatru „Studio”, PKiN, Warszawa, (współpraca: Piotr Damięcki, Henryk Górka, Stanisław Górski, Adolf Szczepiński, Włodzimierz Witkowski).

– IV projekt konkretyzacji LSC dla 6 tys. mieszkańców Poznań-Piątkowo, tzw. fragment Pasma Wielkopolskiego.

1973

– Projekt konkursowy na budynek ambasady polskiej w Waszyngtonie (współautorzy: Piotr Damięcki, Bohdan Dzierżawski).

– Projekt adaptacji gotyckiego kościoła św. Jerzego w Gdańsku do współczesnych potrzeb kulturowych (współautor: Zofia Hansen).

– Adaptacja lokalu ASP na Wybrzeżu Kościuszkowskim do dydaktyki w konwencji Formy Otwartej.

1974 - V projekt konkretyzacji LSC dla 5 tys. mieszkańców Przemyśla, tzw. fragment Pasma Wschodniego (współautorzy: Svein Hatloy, Zofia Hansen, Piotr Damięcki, Mieczysław Czernicki).

1975 - Studium humanizacji miasta Lubina (współautorzy: Edward Bartman, Piotr Damięcki, Hanna Szmalenberg, Henryk Górka, Ewa Kun, współpraca: Piotr Piwowarczyk, Witold Chróścicki, Tamas Banovich).

1976 - VI projekt konkretyzacji LSC dla Legnicy, Lubina, Głogowa; tzw. fragment Pasma Zachodniego (współautorzy: Edward Bartman, Mieczysław Czernicki, Henryk Górka, Piotr Piwowarczyk).

1977/1979 - Studium Fabryki Automatów Tokarskich w Chocianowie (współautorzy: Edward Bartman, Henryk Górka, Ewa Kun, Hanna Szmalenberg, Piotr Damięcki, współpraca: Jolanta Kłyszcz, Elżbieta Myjak, Anna Osóbka, Marcin Świetlik).

1979 - Studium Humanizacji Zakładów Naprawczych Taboru Kolejowego w Pruszkowie (współautorzy: Edward Bartman, Henryk Górka, Hanna Szmalenberg, Elżbieta Myjak, Irena Baszkowska, Barbara Cybulska, współpraca: Andrzej Borcz, Jerzy Dowigałło, Marek Karkoszka, Władysław Klamerus, Konrad Kosiński, Mariusz Simiński, Barbara Śmigulska).

1981 - Studium humanizacji i rozwoju miasta Montreal (współautor: Henryk Górka).

0 notes

Text

Brasilia: ¿Una gran máquina para habitar o una utopía hecha de realidad? [III] | Cristina García-Rosales

El siglo XX y el Movimiento Moderno. ¿Qué ocurrió con la llegada del siglo XX? La necesidad de implantar una fórmula higienista y humanista dentro de un concepto igualitario de fondo, sobre todo, a partir del final de la guerras mundiales, hizo que arquitectos y urbanistas tuvieran el afán de comenzar desde el principio, -entre otras cosas tenían que reconstruir lo derribado- y se reunieran en distintos Congresos Internacionales de Arquitectura Moderna (CIAM) entre 1929 y 1941. Necesitaban establecer las bases para transformar la manera de habitar las ciudades, donde los ciudadanos, antes y durante las guerras, se hacinaban en lúgubres habitaciones dentro de edificios poco ventilados, sin servicios higiénicos y con escasa luz natural. Ciudades que carecían de parques y de arbolado y cuyos habitantes sufrían los estragos de numerosas enfermedades debido a la suciedad del entorno y a la escasez de infraestructuras urbanas. Hablo de la llamada “ciudad industrial”, polucionada e insalubre que hacía urgente la creación de una ciudad nueva para un ser humano nuevo. Se establecieron entonces los postulados de la “Carta de Atenas” (1933) en el IV Congreso de la CIAM, firmada, entre otros, por Le Corbusier que más tarde los utilizó para su ciudad ideal “La Ville Radieux”.

#brasilia#cristina garcía-rosales#IV CIAM#Juscelino Kubitschek#Le Corbusier#lucio costa#movimiento moderno#Óscar Niemeyer#roberto burle marx#urbanismo#ville radieux#artículos

0 notes

Text

Pioneer Architects IV

The forth edition of Pioneer Architects will bring to you a generation of women from the 1930s. Spending their youth in wartime affected on their functionality. Check what is so special about Gaetana Aulenti (Italy, 1927-2012), Denise Scott Brown (USA, 1931), Alena Šrámková (Czech Republic, 1929), Alison Smithson (England, 1928-1993) and Iskra Grabuloska (Macedonia. 1936).

Denise Scott Brown and her husband and partner Robert Venturi are regarded among the most influential architects of the twentieth century.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in the desert outside Las Vegas (1965) | Photo by D. Scott Brown and R. Venturi

When Robert Venturi was named as winner of the 1991 Pritzker Architecture Prize, Denise Scott Brown did not attend the award ceremony in protest. The prize organization, the Hyatt Foundation stated that it honored only individual architects. A practice that changed in 2001 with the selection of Herzog & de Meuron has much to say about the topic.

Alison Smithson was the leading figure in the British Brutalsim movement with her partner Peter | photo by Nigel Henderson Estate

Alison Smithson formed an architectural partnership with Peter Smithson in 1950. They were arguably among the leaders of the British school of the New Brutalism. They were strongly associated with the Team X and its 1953 revolt against ideas of Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) philosophies of high modernism.

The House of the Future was designed for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition (1956), held in the Olympia Exhibition Centre. It was never intended for actual production but only for theoretical discussion.

Designed around a courtyard garden that supplied natural lighting and private outdoor space, there were few windows on the exterior walls allowing the houses to be placed directly side-by-side. For viewing purposes, there was no roof but an elevated platform so exhibition goers could look inside the house from above.

Among early contributions of Alison and Peter Smithson is as well "Streets in the Sky" a popular theme in the 1960s in which the traffic and pedestrian circulation were rigorously separated.

Streets in the Sky by Alison and Peter Smithson.

From the west direct to the east, where slavic architecture language talks in favor of the czech minimalism. Alena Šrámková is known as the first lady of Czech architecture and a pioneer of its minimalism. She has received the Medal for Merit from the Czech president, and the State Award for her contribution in architecture. There has always been controversy surrounding her style of architecture, mostly due to its extreme simplicity.

Alena Šrámková has been active since the 1950s | Photo by Petr Jedinák

Faculty of architecture of Prague Technical University is Šrámková’s building opened in 2010 | Photo by Ivan Němec

In Eastern Europe was not so easy to succeed as architect which didn’t had connection to either a husband or relative powerful in architectural or political field. Iskra Grabuloska was exposed to politics and activism at a young age, as her father was famed Macedonian politician Dr. Boris Spirov, leader of the Macedonian Anti-Fascist Assembly and second president of the Macedonian Parliament. Her masterpiece Makedonium was constructed in collaboration with her husband and sculptor Jordan Grabul.

Makedonium memorial at Kruševo, Macedonia | Photo by Jan Kempenaers

Finishing the presentation with Italian Gae Aulenti graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Polytechnic of Milan (1954). Aulenti conducted extensive cooperation in drafting the magazine Casabella under the direction of Ernesto Nathan Rogers from 1955 to 1965.

Throughout her 60-year career she worked independently in architectural projects, industrial design, interior design and theatrical scenery and as a professor at the School of Architecture of Venice (1960-1962) and the School of Architecture of Milan (1964-1967).

Table on routes - Design in movimento by Gae Aulenti. | Photo via Italianways

59 notes

·

View notes