#IT FUCKING MADE A STORY BASED OFF OF THE ERNEST HEMINGWAY LINE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

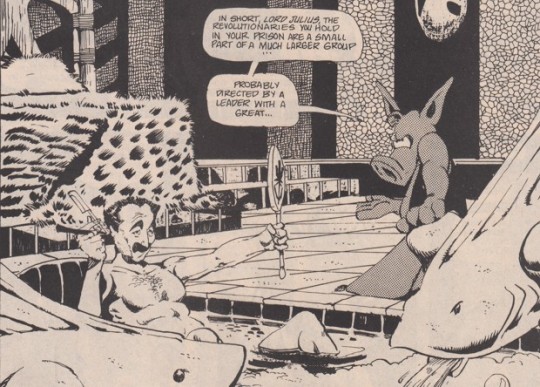

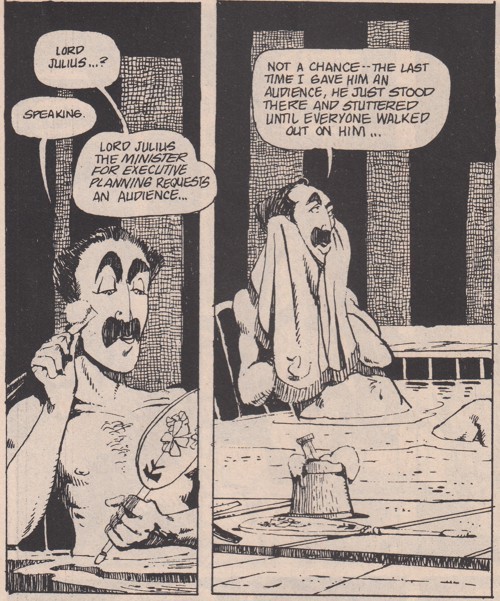

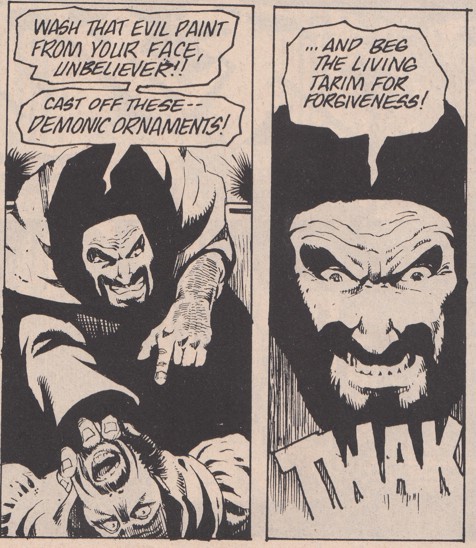

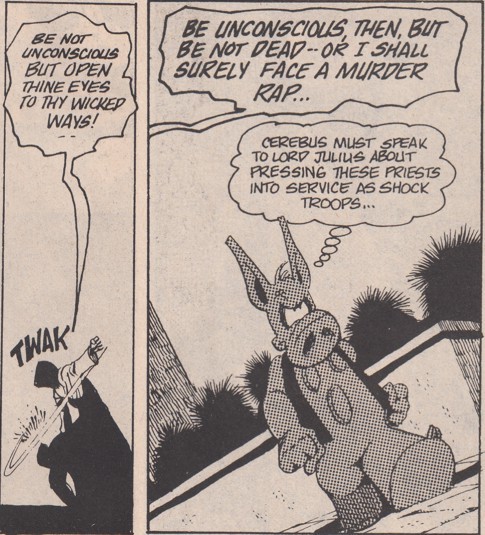

Cerebus #15 (1980)

If the story so far had revealed that Cerebus has a vagina, I could make a hentai joke here.

The first time I encountered hentai was at an anime convention at a Red Lion Inn in San Jose in 1994 or 1995. I went to the convention by myself because I had recently fallen in love with the cartoon Sailor Moon and wanted to get some Sailor Moon LaserDiscs unless it was actually Sailor Moon dolls I wanted. It was so long ago, how am I supposed to remember?! They had a room where they were showing movies and one of the movies I watched was Sailor Moon R: The Movie. It was subtitled which was great because then I had the story memorized for all the times I watched my non-subtitled LaserDisc. But that wasn't the pornographic anime I saw! I don't even remember what that was but I watched some tentacle fucking movie late at night in a dark room with a bunch of other sweaty nerds. I didn't know that was what was going to happen though so I didn't have my dick in my hands like the other guys probably did. I was as shocked as anybody when they first find out that cartoons where women get fucked by tentacles exist! I mean, how many penises does an alien need?! I grew up thinking the little gray aliens had zero! That Red Lion Inn was the same one where I played in a couple of Magic the Gathering tournaments. Being in a dark room with a bunch of horny anime fans was less awkward and uncomfortable than playing Magic the Gathering against Magic the Gathering fans. Most of them probably couldn't believe they were actually playing against such a cool and handsome dude. It really threw them off their game when I would say things like, "Yeah, I've touched a couple of boobs. I attack with my Serra Angel." I know what you're thinking: "Anime, comic books, and Magic the Gathering?! This awesome dude must have owned every single Stars Wars figure too!" Aw, you're too kind! I'm blushing! But obviously I never owned Yak Face. "A Note from the Publisher" is still being published so I guess Dave and Deni are still married. In his Swords of Cerebus essay, Dave Sim discusses "Why Groucho?" It seems to mostly come down to this: Dave Sim enjoyed the characters of Groucho Marx as a teenager and memorized a lot of their lines. He also mentions Kim Thompson's review of Cerebus in The Comic Journal (the first major review of the series) in which Kim praised Sim's ability to make his parody characters transcend the parody to become unique creations of their own. This review gave Sim the confidence to put Groucho in the role of Lord Julius. Which worked out so well that Sim later adds Oscar Wilde, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Margeret Thatcher, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Woody Allen, Dave Sim, and the Three Stooges into the story. I'm sure I'm missing some but I can't remember every aspect of this 6000 page story. Was The Judge also a parody of somebody? Was the Regency Elf based on Wendy Pini? I don't know! I'm sure I'm missing a lot of references in Cerebus simply because I haven't experienced all the same knowledge sources as Dave Sim. Just like I'm missing a super duper lot of references in Gravity's Rainbow because nobody in the history of ever has experienced all the same knowledge sources as Thomas Pynchon. I've been reading Gravity's Rainbow (for the first time but also the third time because I'm basically reading it three times at the same time. You'll understand when you read it) and I'm surprised by how funny it is. I don't think anybody ever described it as funny or else I'm sure I would never have stopped reading it multiple times prior to this time when I'm actually going to finish it. Although I suppose when I read Catch-22, I had done so on my own so nobody ever told me how funny that book was either. But for some reason, Catch-22 lets you know it's going to be a funny book pretty quickly. Gravity's Rainbow is all, "Here is a description of an evacuation of London which is just stage setting because, you know, the bombs have already blown up, but it makes people feel safe. And after that, how about a scene where this guy makes a bunch of banana recipes for breakfast. Is that funny enough for you?" Oh, sure, there are some funny moments like when that one guy pretends a banana is his cock and then some other guys tackle him and beat him with his own pretend cock. But there's a gravity to the scene that doesn't lend itself to the reader thinking, "Oh, this is a funny book!" But if you make it far enough, you start realizing, "Hey! I'm not understanding this!" So then you reread the section and you start realizing, "Hey! I'm laughing at this stuff! This is pretty funny!" Plus there are a lot of descriptions of sexy things that I'm assuming are really accurate because Pynchon is obsessed with details.

Anyway, I was supposed to be talking about Cerebus, wasn't I?

A Living Priest of Tarim crashes Lord Julius' bath to scold him about a party Julius is giving in a fortnight (which is the amount of time your kid has lost to a video game). I don't know why the priest has to declare he's a living priest. You can tell that by the way he's shouting and foaming at the mouth. Although this is a Swords & Sorcery book so I suppose there are many dead creatures that also shout and foam at the mouth. Sometimes I forget I'm reading a fictional book and wind up ranting and raving about stuff that I'm supposed to just assume is fine. Like when I read The Flash and nothing in it makes any sense at all because The Flash should never have any trouble stopping crime or saving people from natural disasters. The comic book should be over in two pages. Even the writers, at some point, realized how ridiculous Flash stories were and decided the only way to make them believable was to have The Flash battle other super fast people. But that just meant Flash stories basically became bar-room brawls. Two people with super speed fighting is the same as reading a story about two people without super speed fighting. Boring! Some writers even decided that maybe a telepathic monkey would make things more interesting and I suppose telepathic monkeys make everything more interesting so kudos to them. I was going to go on a long rant about telepathic monkeys but then I realized how much I love the idea of telepathic monkeys so why should I create an argument against them? More telepathic monkeys, please.

This made me laugh out loud. Not as much as the chapter in Gravity's Rainbow where the old woman forces Slothrop to eat a bunch of terrible candies. But then it isn't a competition, is it? I mean, I guess it's a competition for my time which is why I haven't written a comic book review in a week or more. Blame Thomas Pynchon for being so entertaining (and also Apex).

Baskin, the Minister for Executive Planning, has come to let Lord Julius know what the revolutionaries have revealed while being tortured. The only bit of useful information was one prisoner's last words: "Revolution...the pits." Cerebus immediately assumes "the Pits" is a location and not a summation of the prisoner's feelings about revolution which led to torture which led to his death. Cerebus, being the Kitchen Staff Supervisor, begins an investigation into The Pits. His first step: threatening the Priest of the Living Tarim. Which makes me realize I transposed the word "living" in the previous encounter with the priest and went on a digression that makes no sense to anybody who has read and somehow remembers that particular panel. I'm sure they were scoffing and snorting and exclaiming to their pet rat, "What a stupid fool loser this Grunion Guy is! Living Priest of Tarim! HA! Ridiculous! What a moronic mistake! He has made a gigantic fool of himself!" I don't know that the almost certainly imaginary people who called me on my mistake as they read this have a pet rat but I do know there almost certainly isn't another imaginary sentient being in the room with them. Cerebus learns that The Pits are Old Palnu that lies under current Palnu. It was destroyed in a massive earthquake long ago and the new city built over the top of it. It's like a Dungeons & Dragons module but with a lot less treasure.

This scene reminded me that I need to finish rereading The Boomer Bible: A Testament for Our Times (which is what it was called in the 90s but is just as accurate for today).

Cerebus and Lord Julius engage in another typical misunderstanding (it's not hard when only half of the people in the conversation care about making sense) which ends up with Lord Julius deciding that the location for the Festival of Petunias will be The Pits. This complicates Cerebus' job of not allowing Lord Julius to be assassinated because the assassins are most likely housed in The Pits (along with their giant snakes (*see cover)). Lord Julius, Baskin, and Cerebus descend into The Pits to find a suitable location for the Festival of Petunias. In doing so, they wind up in a trap and confronted by a masked revolutionary of the "Eye of the Pyramid." Which is odd because you usually have to murder at least a dozen kobolds and several goblins before you reach the room with the boss in it.

Typical unbalanced beginning level module. A giant snake as the first encounter!

Cerebus manages to defeat the giant snake by crashing it headfirst into a wall. The wall winds up being a key support structure and the roof collapses. Everybody makes it out alive but the masked revolutionary evades capture. He will be back next issue to ruin the Festival of Petunias. Aardvark Comment is still just a mostly standard comic book letters page. I'll probably stop discussing it until people start criticizing Dave. Right now it's just "This comic book is great!" and "Keep writing, Dave, and I'll never think ill of anything idea you espouse!" while Dave replies, "I owe my fans everything! I can't wait until I can stop feeling that way and start jerking off onto my art boards and selling those as pages of Cerebus!" Cerebus #15 Rating: A. Good story, good Lord Julius dialogue, good Living Priest of the Living Tarim scenes. I wholeheartedly endorse this comic book and Dave Sim. No way a guy with a sense of humor like this is going to go off the rails, right?!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five books

My fave @writcraft / @writsgrimmyblog tagged me to “list five books that made a deep impression on me at different points in my life. Not necessarily your top five favourite books ever, nor even books you’d recommend to someone else now, but five books that were important at the time, whether you loved them or hated them." Thanks for the tag!

1. Vinciguerra by Elaine Castillo

I read this kid’s fic wayyyy wayyyy back in the day and it is one of the reasons I ever picked up a pen and started writing stuff of my own. A lot of my style and subject matter can be traced back to this kid’s writing. When she published this book of short stories, it FLOORED ME. It’s so wild and emotive and a fucking tour de force of poetic writing style and delicious, complex tension and cutting dialogue. I still re-read it every few years.

2. Harry Potter series

One of the main reasons I got into reading, writing and fandom in my teens. I found a home in these books and the communities around them that I hadn’t found anywhere else. I wouldn’t be me without these books.

3. Crush by Richard Siken

Anyone that follows me on twitter or insta or knows me IRL will know I’m obsessed with these poems and the wild, beautiful, heartbreaking worlds contained within them. So much of my own writing has been inspired by turns of phrases or concepts in this book. I’m low key kind of working on a hospital amnesia Tomlinshaw AU based off of several poems in this book. The book is glorious and intensely personal to me, and I can’t read lines like, “These, our bodies, posessed by light / Tell me we’ll never get used to it,” or “But tell me you love this / tell me you’re not miserable,” or “For a while I thought I was the dragon / I guess I can tell you that now,” without clutching my heart.

4. A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

Another one of those books that I think taught me how to write, and how to hold back on exposition, and how to only include the things that are important, and not waste words on things that aren’t. I write a lot of short, sharp, heartbreaking stuff, and my affinity for that style came out of studying Hemingway when I was younger. This novel is especially close to my heart, because it shows how trauma fractures narration, how storytelling falls apart when your memories are too chaotic to make sense of. It’s beautiful, but I haven’t read it for a long time.

5. The Man Who Loved Yngve by Tore Renberg

This book was the first time I ever truly saw myself in a piece of writing - queer, confused, brave and terrified and struggling to make sense of growing up and living in this little bourgeois shit town in Norway. The protagonist in this is and his friends were very much me and my friends, and even though it’s set in the 90s and I grew up a decade later, it was very much telling my story, and the politics in this were very much the politics I had around me growing up. It’s truly gorgeous and heartbreaking, and will forever mean the world to me.

Thanks for the tag, love! I’ll tag @immoral-crow, @akamine-chan, @sommerfuglvinge & anyone else that wants to do it!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writer’s Block Is Bullshit -- Here's Why You're Stuck

For a substantial number of years, at the onset of my writing career, I absolutely believed in writer's block. The inability to breakthrough while writing an article, book or short story usually crept its ugly head at two precise moments — the seconds before sitting in front of a computer to get to work and the hours spent thinking about the task that needed to be completed.

Yeah, basically writer’s block happened all the damn time.

My form of writer's block always involves chasing the "feeling." Being overcome with the motivation or inspiration to write. To be in the mood, in my case, demanded this perfect scenario of setting, time of day, physical sensations and a hundred uncontrollable factors that must align.

Eventually, I came to a few realizations. First, nothing in life will ever be perfect. Second, I realized writer’s block is fictional, and I was just fucking scared. What if I put all my eggs in one basket and that basket is made of wet paper?

Now I know the truth.

Writer's block is a bunch of bullshit. Writer’s block doesn’t exist. As much as every working writer wishes it were an actual ailment, I repeat, writer’s block does not exist. Writer’s block is self-doubt. There's something you don't want to write, think you can't write or feel you're unqualified to write.

You don't have writer's block you're just scared of something. First, let’s figure out what…

The Common Fears That Cause Writer's Block

Here are some of the common issues that plague writers.

The “I Suck” Syndrome

Every writer, even the literary greats, begins the writing process with an awful first draft. No author vomits perfection all over the page every single time he or she sits down at a keyboard.

Most writer’s block issues can be traced back to personal feelings about yourself and your writing ability. You believe you haven’t written anything “great” in a while and have lost your mojo. The work on the page isn’t up to your often immeasurable standards, and it’s causing internal conflict. You don’t want to spend another minute sitting in front of a computer.

Here’s the bad news — you do suck. Here’s some fantastic news — every writer sucks (at some point). But you're in good company with every other writer ever. Welcome to the club!

“The first draft of anything is shit.” Ernest Hemingway

You Have “Nothing To Say”

One of the most prolific writers of the last 50 years is Robert Shields. You’ve likely never heard of him because he never published any work. Well, not really. He did, however, bang out an estimated 37.5 million words over a few decades.

“Starting in 1972, Shields was hit by the urge to document every moment of his life in his diary. It was estimated that he spent about four hours everyday typing, relaying the day’s most major events alongside the most brutally minute details while sitting on his back porch in his underwear.

He described what he had for every meal, what kind of heartburn he had (along with what he took for it and how long it lasted), who stopped by to visit him, and what he fed the cat. He was particularly precise about his bowel movements, documenting when they happened and every detail about what came out of him. (He even had a number of different ways for cataloging urination.)”

Everyone has a story. Everyone's life is interesting. Even though Robert Shields and his list of daily activities. Admit it — even though you don’t know Shields personally and every detail of his life sounds monotonous and crazy, you kinda want to see at least one of his journals.

You’re putting something off because you feel like you don’t anything original to say or add to the topic. You’re wrong. Every person adds their own unique angle to a story, and other people are interested in reading those opinions.

Famous Writers (Who Are Also My Friends) Give Advice About Writer’s Block

In case you’re thinking “who’s this idiot saying writer’s block doesn’t exist?” Well, first off, my name is at the top of this website. That’s who I am. Second, I’m not the only writer that’ll say bluntly that writer’s block is BS.

I reached out to fellow freelancers, writers, editors, authors and a few people who write just for the fun of putting pencil to pad (or digits to keys). I gave them one prompt. “Writer’s Block. Go!” They shared the first thoughts that sprung to mind.

“Anyone who says they have writer's block isn't writing...THAT is the problem. Writer's block is an excuse for distraction. Write until it's not there.” - Jason Donnelly, author, Gripped

“Some people think writer's block is like a dam, where all the ideas just get backed up and will start flowing again eventually. Others think it's a drought, and eventually, the rain will come. Writer's block is when the river is still flowing as usual, but the water's turned to piss. The flow is still there, but there's nothing worth drinking.” - Daniel Coffman, author, Four From Below

“Writer's Block is a funny thing. I think it comes from trying to come up with something perfect. The perfect topic. The perfect opening sentence. The perfect follow-up sentence. The perfect closing sentence. And for the most part, we overthink it. We end up blocking ourselves from thinking of what to do next because we just want to get the damn thing right.” - Rey Moralde, writer, The No-Look Pass

"My writer’s block generally stems from self-doubt, when I start wondering why the hell anyone might care what I have to say about a subject. I'm usually working on multiple projects at the same time, and I often find that if I'm struggling with one, it cripples my other writing because it starts occupying all my thoughts and I'll set aside time to work on it, then spend all that time thinking about how stupid it is and what a colossal waste of time it has been and how if I actually practiced what I believe about sunk costs I would scrap it altogether and move on. Being in the news business sort of forces you to get over writer's block when it comes, since sometimes you simply have to cover something, and even if you suspect all your words are dumb and bad, you need to be willing publish them to ensure future paychecks. And after writing professionally in some form for the past 10 years, I've come to understand that there's not always a correlation between the stuff I write that I think is good and the stuff people seem to enjoy reading.” — Ted Berg, sports columnist, USA Today

“The first thing that comes to mind when you say Writer's Block is a scene from the best running moving ever: Run Fat Boy Run. He hits the wall in running his first marathon, and it's a wall. No really, a wall. I think that's what writer's block is like. I don't want to spoil the end of the movie, but he gets through it, just like I do in writing life.” — Jen Miller, author, Running: A Love Story

“Writer’s block is the unavoidable flu of writing. It must be pushed through, survived, repeated, and conquered.” - Elysia Regina, writer

How To Break Writer’s Block

I’ll humor you for a few minutes and pretend writer’s block does exist but I won’t call it writer’s block. Instead, I’ll say you’re stuck. Here are some ideas and items to get the gerbils in your head back up and running on those wheels.

The first method is one of my own creation, named after one of my favorite professional wrestlers.

The Lie, Cheat and Steal Method

Eddie Guerrero is a former world champion and a member of one of the most revered families in professional wrestling. Right before his untimely passing in 2005, Guerrero was one of the most popular wrestlers in the WWE. During the height of his heel run (that’s wrestling speak for a “bad guy,” Guerrero preached the three tenants of getting ahead in wrestling or any walk of life. Lie. Cheat. Steal.

Guerrero’s advice isn’t practical or sound for any profession other than the fictitious world of professional wrestling, but it’s solid advice for a writer. Here’s how it work…

Lie: Sit down with a blank piece of paper and conjuring up the biggest bullshit lie ever. It can be about yourself or even your subject. Write a lie so massive it would be impossible for anyone to ever believe. Now, prove that lie to be true. Make your prose convince you, a family member or total stranger that this massive lie is a stone cold truth. I’m certain that by the time you’re done either a new story, new article idea or angle to a project you’ve been putting off for months will emerge.

Cheat: Go back into your archives and find a finished article or story. Now take the opposite argument. If it’s fiction, write the story in a new direction. If the story was about a man, make it about a woman. If the article was about donating time to shelter animals, take the opposite stance. (Yes, that’s a jerk thing to write about, but this is an exercise in breaking writer’s block). Find the piece you’re most proud of and turn it on its god damn head.

Steal: Grab your absolute favorite novel off the bookshelf. Open it to a random page and begin reading. Find the first sentence that really grabs you by the genitals and copy it, word for word, into a new document. Start typing a brand new story based on that one line. When you get far enough, go back and change that first line to your own words. I’m not telling you to literally steal another writer’s work, just temporarily channel their mojo for prose.

Take A Runner’s Approach To Writing

Jen Miller alluded to this approach in her quote earlier in this text but one of the best approaches to writing is similar to how people tackle the task of training for long distance runs. A runner doesn’t always feel like running, especially those long distant athletes who have to log miles and miles every single day to stay in top performing condition.

So what’s their secret to running on the days when they just don’t feel like it? They just start running. It’s that damn simple. They lace up the sneakers and hit the road. The same goes for writing. What should you do when you don’t feel like writing? Sit down and write. Every mile is a step towards running farther. Every sentence is a step towards something, even if it’s absolute gibberish.

Buy A Writer’s Block Book

There are countless apps and websites dedicated to breaking writer’s block through writing prompts. I’ve tried a few, mostly just for inspiration, and my far and away favorite is 642 Things To Write About.

“This collection of 642 outrageous and witty writing prompts will get the creative juices flowing in no time. From crafting your own obituary to penning an ode to an onion, each page of this playful journal invites inspiration and provides plenty of space to write.”

Buy A New Notebook

Five-and-dime stores were crack to me as a kid. If you’re unfamiliar, or not as ancient, a five and dime store was a step above a dollar store but not quite a Walmart. Places like Murphy’s and McCrory’s littered the land in my youth, and I loved every single one of them. What I loved most about these stores was that they sold just about everything. Toys, clothes, games, housewares, tires, magazines, records. I’d get lost in the aisles and never want to leave.

A similar feeling overcomes me each time I step foot in a stationary store. Just staring at all of the journals, pens, and accessories for writing and I GET SO FIRED UP!

How Other Writers Bust The Block

“It's like anything else: Ask for help. Sweeten the deal with cookies if you have to. It also helps to take a walk Or just physically move. I get my best ideas when I'm driving or in the shower or boxing, so basically never when I am in a situation where I can actually write something down.” - Jessica Sager, writer

"The best way to conquer writer's block is to engage your brain that can mean anything from listening music, watching a favorite show, or sometimes I find a good walk gets things moving. Failing that, sometimes it helps just to write and I mean write anything, even if it doesn't make sense. Sometimes just the act of putting words on paper, even if it's putting words on virtual paper, can get the juices flowing." — Karl Smith, editor and former newspaper columnist

“The best cure I've found for writer's block is pushing forward through something even when I think it sucks, because I'm not going to get anything else done until I'm finished with it anyway and because there's a non-zero chance the dreck I burp out when the words aren't flowing will prove more popular than the stuff I write when I feel great and invincible and dope.” - Ted Berg

“I'm a big fan of music, usually a good instrumental track works. I mix it up between jazz and new stuff like Tycho. Wine also works really well” -- Andrew Ward, writer & strategist

“Step away from it and do something else. Something out of your norm. Whatever you need to concentrate on it. Then take a nap. Or just fuck off for as long as you want to like George R.R. Martin.” — Carl Ceposki, writer

The End Of Writer’s Block (For Now)

If you still believe in writer’s block, there could be something deeper behind the inability to sit down and get work done. It’s up to you to figure out the issue and fix it. None of these problems ever go away. You’ll still have doubt, think you’ve got nothing to say or continuously chase the perfect “time” to put out a best seller or finish a work project. In the end, the only way to break through is to literally break through.

If worse comes to worse, and the words don’t come, just write about what you know. As Charles Bukowski put it “Writing about a writer's block is better than not writing at all.”

Chris Illuminati is the author of five books, countless articles, a billion post-it notes and a 323 million incomplete works of fiction.

FOLLOW CHRIS ON: FACEBOOK | TWITTER | INSTAGRAM | TUMBLR

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like Most Americans, I Was Raised to Be A White Man

Like most Americans, I was raised to be a white man: I read William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. I read F. Scott Fitzgerald and Charles Bukowski. I came to identify with the emotionally disengaged characters, the staccato sentences, the irreverent dirty old man voice. The books I read asked me to imagine the power I might have. I got women pregnant and then worried that they wouldn’t get an abortion, tying me down forever when all I wanted to do was continue experiencing my freedom. I wrote poems about the absurdity of writing poems, enjoying the decadence of imagining my readers drinking in my disregard for them. Being likeable, explaining oneself to others, were not prerequisites of protagonism. I watched women move—their hips in dresses, their lips on glasses, their breasts heaving. All of it offered up to me, to enjoy, to consume. The fact that I was a brown woman was not something that seemed immediately relevant when I was younger.

I moved through the world with this sense that I would have access to the same kind of power as the protagonists of the books I read and movies I watched. Of course we all identify with white protagonists—they’re almost always the heroes, the ones with the power to change things, to affect things rather than simply be affected.

As James Baldwin put it,

You go to white movies and, like everybody else, you fall in love with Joan Crawford, and you root for the Good Guys who are killing off the Indians. It comes as a great psychological collision when you realize all of these things are really metaphors for your oppression, and will lead into a kind of psychological warfare in which you may perish.

Article continues after advertisement

And whether it be because you are female, brown, queer, or in any other way visibly other from white, able-bodied, cisgender, heterosexual men, it feels like a kind of violence when you suddenly have to reckon with the differences of the body you’re in. Not because of some innate qualities embedded in those differences, but because of all the assumptions made about the body you’re in that you have to confront.

Coming of age in particular constitutes a jarring emergence of double-consciousness—of being forced to see yourself through the eyes of others even as you’re still trying to form a sense of self.

During a summer trip to Florida to visit relatives, my aunt, poolside, remarked upon my 14-year-old form in a bathing suit: When did you get breasts? How big are those things? I felt ashamed—and not just because my body was suddenly a spectacle. I already knew it was. How big are those things was precisely how I felt about the strange lumps of flesh that had sprouted from my body. They were separate from me.

While I was deeply embarrassed by my aunt’s commentary, there was an element of identification, of relating to her perspective. It seemed more of a farce to me that people could look at me and assume that this newly hatched female form was somehow me instead of something that had happened to me.

And yet, that is the presumption: that the general shape you come to take imbues you with certain “female” traits—to be accommodating, empathetic, emotional, sexual (but not too sexual!). Our bodies become shorthand for a grab-bag of assumptions, some of which we grow into, some of which we bristle against.

Article continues after advertisement

My femaleness has always been something that seemed to fit me poorly—at turns an oversized garment I could not fill, or some skimpy rag out of which I spilled.

I’ve already made a mistake by calling the femaleness “mine.” It’s never felt like a thing I owned so much as a general shape I grew into that seemed to offer me up for public consumption.

“I moved through the world with this sense that I would have access to the same kind of power as the protagonists of the books I read and movies I watched.“

The phrase “gender is a construct” might strike some as academic claptrap, but ask any woman how they were treated before and after puberty, and you’re well on your way to understanding not just the truth, but how fucked up that truth is—the extent to which the entire world, and the way you must navigate it, is irrevocably changed.

Also at 14, I remember walking down the street with K. and H., my closest friends, in the North Carolina college town where I grew up. We flinched when three men started catcalling us. Yeah, baby. Look at that ass. I remember feeling bewildered and disarmed. Having a reputation as being the outspoken one, I felt vaguely responsible for doing something about it. But I did nothing.

One of the most humiliating aspects of that moment was that in doing nothing, it felt like I had allowed them to do something to us. This is one of the most nefarious aspects of predatory behavior: it makes the target of the behavior feel complicit. You might be going about your business, and then someone who has more power than you demands engagement—the kind in which even your refusal does not always free you, forcing you to play a part in a scene you had no interest in even auditioning for.

A couple hours after the encounter with those men, my friends and I piled back into the car and started our drive home. That’s when I spotted the men, still roving the sidewalk not far from where we’d encountered them. Wait! I told H., who was driving. Slow down. I rolled down the window, started shouting at them the very same things they had lobbed at us: Yeah, baby. Look at that ass. It was a humbling and educational moment because, of course, they loved it. I was startled in my naïveté: I had turned the tables, but the tables had not turned.

I didn’t have the language for it then, but this was one of the first times I experienced how my words would always be shaped by my appearance—how they would be heard differently. How they would often weigh less. How the expectations of my femaleness would become a thing I would repeatedly have to explain, justify, respond to, contradict.

The same was true of my brownness. Growing up in the South, I quickly learned how to translate the questions “What are you?” and “Where are you from?” Obviously, “human” and “North Carolina by way of Connecticut and California” didn’t cut it. What they wanted was for me to explain the parts of me that weren’t white. I came to accept the question, and as I got older, played around with responses. Sometimes I’d say I was “half white” (and in response to “What’s the other half?” I’d add “half non-white”). Sometimes I’d say I was “mostly human.” I played dumb, and answered as literally as possible in an attempt to force people to examine what they were saying, what they actually wanted to know, and whether it was a reasonable thing to ask of a virtual stranger.

This was hardly unique to my experience of growing up in the South. When I was in my twenties, I spoke to a literary agent in New York about a collection of short stories I had written. She was excited by my writing, but concerned that there wasn’t enough of an “overarching emotional arc or theme” to connect the stories. “For instance,” she wrote,

Jhumpa Lahiri’s short stories have something larger to say about first generation Indian-Americans—about marriage, family dynamics, adjusting to a new country, etc., and I’m not quite sure what you’re trying to say here . . . I’d like to see more of your background woven into the stories.

Better yet, one of the stories in the collection I had shared with her included a protagonist who was an Indian writer in conversation with her agent:

“Nobody biting yet,” the agent writes, suggesting that I start something new—something that “takes advantage of your heritage. . . . How about a novel with an Indian-in-America theme? Sort of Jhumpa Lahiri-ish?”

It was darkly comical that the real-life agent was echoing the fictional situation I had written. At the time, I took her feedback to heart. Yet I found myself wondering about what she meant by my “background.” My primary identity is not as a first-generation Indian-American. I identify more as an ambiguously brown American—one who decided to learn Spanish in part because so many people assume I’m Latina, that I figured I should be able to at least say, “No soy Latina. Mi padre es de India y mi madre es blanca—de Estados Unidos.” The unifying theme in the stories I gave the agent was precisely this: my characters were shape-shifters whose appearances were often in tension with their self-identification.

I abandoned those stories, and it wasn’t until almost a decade after my conversation with that agent that I thought: Would she ever have said “I’d like to see more of your background woven into the stories” to a white male writer?

“I didn’t have the language for it then, but this was one of the first times I experienced how my words would always be shaped by my appearance—how they would be heard differently.”

When you ask what terrain a white male fiction writer might explore, the sky is generally the limit. (In fact, it’s rare to even see that question posed.) But if you’re queer, brown, female, differently abled, etc., it’s expected that you’ll discuss that. More than discuss it, you’re often tasked with explaining it—what happened, why you look the way you do, why you identify the way you do in contrast to the expectations projected on you based on your appearance. The conversation you’re supposed to have is the conversation white folks would like to have based on what they see. They’re the kinds of questions we almost never think to ask white folks themselves—particularly white men.

As an “other,” the complex human you are ends up being reduced to a handful of visible traits. It’s a kind of censorship: the world’s questions shape how you define yourself, how you explain yourself. Even individuals and organizations with good intentions end up reinforcing this heavily policed line: there are a number of scholarship and funding initiatives for marginalized individuals, but to be eligible or to have a real chance of being selected, you usually have to prove that this identity is core to who you are and the work you do.

To move beyond the perceived notions of your identity can be destabilizing for other people. As a teenager, I recall a drunken frat boy who, after seeing me teaching a friend basic dance steps, ambled over to ask what kind of dancing we were doing. I told him it was salsa. His brow furrowed. Then he asked, “What are you?” I translated his question, replied that I was half Indian. I watched his face travel a journey of utter bewilderment. There were about eight long seconds of silence before he came out with: “Then . . . shouldn’t you be Indian dancing?” Despite the offensiveness of the question, I laugh when I think about it. In the moment, I recall telling him that I knew he had had a lot to drink, but that I wanted him to try to remember the conversation when he woke up the next morning, and to think about what he’d assumed and why it was problematic. He nodded, a little confused, the effort of earnestly trying to follow my instructions written on his face.

I sometimes get nostalgic about the transparent way that boy responded to me. I knew exactly where he stood. He felt like less of a threat than so many of the folks who count themselves as allies while their bigotry goes unexamined, closeted behind a veneer of progressive cred or good intentions. This outright confusion or even straightforward bigotry and sexism can be easier to navigate than the more veiled way so many Americans—particularly those on the Left—deal with their confusion about, and fear of, otherness.

__________________________________

Good read found on the Lithub

0 notes