#INSTEAD OF BEING BASED ON WHATS EASIEST TO SALE AND STIFLING CREATIVITY OVER CAPITALISM

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

But, having just reread the stuff, some of it for the first time since the original publication, I'm mildly amazed at how cohesive it all is. It really does form a single, unified narrative—what today would be called a graphic novel. Does that mean that when we introduced Talia we knew that eventually her father would be presumed dead, and she and Batman would finally enjoy a walk into the sunset? No, certainly not. Rather, I'm sure, we understood the characters well enough to keep them from doing anything alien to them and, with that as a constant, the narrative grew organically, each incident suggesting others. The overall design was never imposed on the material; rather, it emerged gradually as we produced the individual episodes. We were guys sticking tiles up on a wall, just interested in covering the space, and after a while, Look at that! Darn if we didn't make a mosaic! This kind of process is denied to storytellers who create conventional plays, movies, novels-forms that demand structure with clearly defined beginnings, middles, and ends. It lets the writers and artists share, at least to some extent, in the audience's pleasure of anticipation, of being surprised by what happens next. It can be an absolute joy.

(full ID below cut)

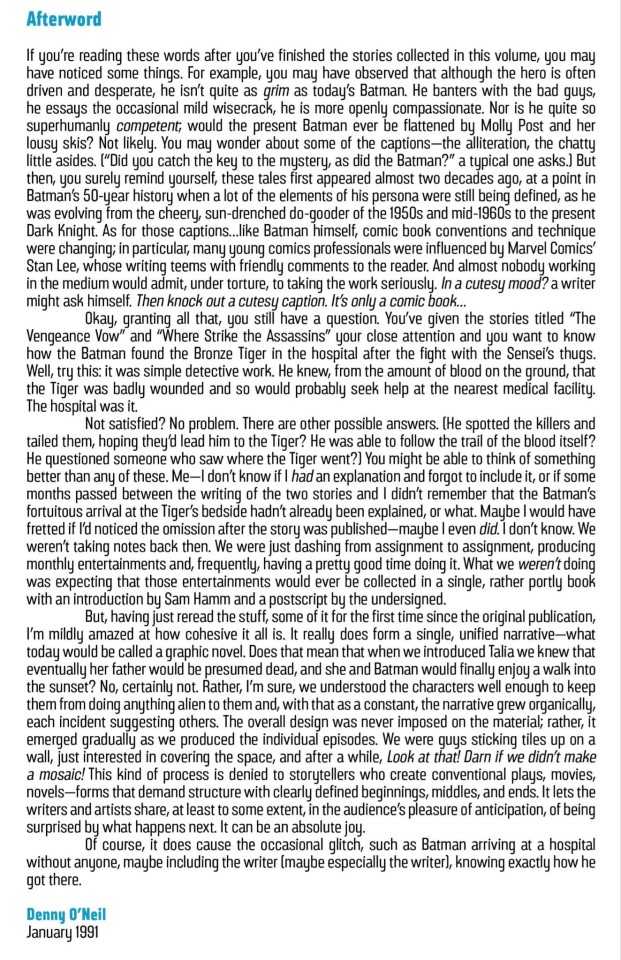

[ID: an afterword by Danny O'Neil on the collective comic ‘Batman: Tales of The Demon’ from 1991. Text reads:

If you're reading these words after you've finished the stories collected in this volume, you may have noticed some things. For example, you may have observed that although the hero is often driven and desperate, he isn't quite as grim as today's Batman. He banters with the bad guys, he essays the occasional mild wisecrack, he is more openly compassionate. Nor is he quite so superhumanly competent; would the present Batman ever be flattened by Molly Post and her lousy skis? Not likely. You may wonder about some of the captions—the alliteration, the chatty little asides. (“Did you catch the key to the mystery, as did the Batman?” a typical one asks.) But then, you surely remind yourself, these tales first appeared almost two decades ago, at a point in Batman's 50-year history when a lot of the elements of his persona were still being defined, as he was evolving from the cheery, sun-drenched do-gooder of the 1950s and mid-1960s to the present Dark Knight. As for those captions...like Batman himself, comic book conventions and technique were changing; in particular, many young comics professionals were influenced by Marvel Comics' Stan Lee, whose writing teems with friendly comments to the reader. And almost nobody working in the medium would admit, under torture, to taking the work seriously. In a cutesy mood? a writer might ask himself. Then knock out a cutesy caption. It's only a comic book...

Okay, granting all that, you still have a question. You've given the stories titled “The Vengeance Vow” and “Where Strike the Assassins” your close attention and you want to know how the Batman found the Bronze Tiger in the hospital after the fight with the Sensei's thugs. Well, try this: it was simple detective work. He knew, from the amount of blood on the ground, that the Tiger was badly wounded and so would probably seek help at the nearest medical facility. The hospital was it.

Not satisfied? No problem. There are other possible answers. (He spotted the killers and tailed them, hoping they'd lead him to the Tiger? He was able to follow the trail of the blood itself? He questioned someone who saw where the Tiger went?] You might be able to think of something better than any of these. Me—I don't know if I had an explanation and forgot to include it, or if some months passed between the writing of the two stories and I didn't remember that the Batman's fortuitous arrival at the Tiger's bedside hadn't already been explained, or what. Maybe I would have fretted if I'd noticed the omission after the story was published—maybe I even did. I don't know. We weren't taking notes back then. We were just dashing from assignment to assignment, producing monthly entertainments and, frequently, having a pretty good time doing it. What we weren't doing was expecting that those entertainments would ever be collected in a single, rather portly book with an introduction by Sam Hamm and a postscript by the undersigned.

But, having just reread the stuff, some of it for the first time since the original publication, I'm mildly amazed at how cohesive it all is. It really does form a single, unified narrative—what today would be called a graphic novel. Does that mean that when we introduced Talia we knew that eventually her father would be presumed dead, and she and Batman would finally enjoy a walk into the sunset? No, certainly not. Rather, I'm sure, we understood the characters well enough to keep them from doing anything alien to them and, with that as a constant, the narrative grew organically, each incident suggesting others. The overall design was never imposed on the material; rather, it emerged gradually as we produced the individual episodes. We were guys sticking tiles up on a wall, just interested in covering the space, and after a while, Look at that! Darn if we didn't make a mosaic! This kind of process is denied to storytellers who create conventional plays, movies, novels-forms that demand structure with clearly defined beginnings, middles, and ends. It lets the writers and artists share, at least to some extent, in the audience's pleasure of anticipation, of being surprised by what happens next. It can be an absolute joy.

Of course, it does cause the occasional glitch, such as Batman arriving at a hospital without anyone, maybe including the writer (maybe especially the writer), knowing exactly how he got there.]

#HEY REMEMBER WHEN COMICS WERE GOOD AND THE CHARACTERS HAD PERSONALITY AND STORIES WERE ALLOWED TO PROGRESS AND BUILD NATURALLY#REMEMBER WHEN COMICS WERE TREATED AS AN ARTFORM AND OPPORTUNITY TO DEVELOP A STORY IN THIS UNIQUE EXPERIENCE OF AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT#INSTEAD OF BEING BASED ON WHATS EASIEST TO SALE AND STIFLING CREATIVITY OVER CAPITALISM#CAUSE YEAH :/#c: batman: tales of the demon

20 notes

·

View notes