#I would like trisolaris because the ocean sunfish would not survive there

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Real Life Biology of the Three Body Problem Series

In the first book of Liu Ci Xin's Three Body Problem series, we are introduced to our main antagonists, the Trisolarans. Whilst we never get to see them directly, we are shown some of their biology via the game that our protagonist plays.

ID: A grand domed palace in a chinese style sits in the background of the image. The foreground has hundreds of ancient Chinese soldiers holding white placards on sticks. Two people dressed in Chinese armour can be seen riding horses towards the palace.

In the game it is revealed that Trisolaris, the planet in the Alpha Centauri system on which the aliens reside, revolves around not one, but three suns. As such, the system is subject to the classic physics conundrum of the three body problem (after which the first book in the series is named), which states that for most initial conditions the trajectories of three celestial bodies is chaotic and difficult to predict.

This means that Trisolaris experiences very extreme, unpredictable conditions, divided into "stable eras" and "chaotic eras". Stable eras come about when Trisolaris settles into orbit around one of its three suns, bringing relative prosperity to the planet. However, chaotic eras result in disasters, such as extreme droughts, seemingly endless nights, and even changes in gravity. The first novel partially revolves around the Trisolarans attempting to see if humans could collectively solve the three body problem and bring some level of predictability to their planet.

During the course of the game, it is revealed to the protagonist (and us, the readers), that in order to cope with the devastation and unpredictability of chaotic eras, the Trisolarans can dehydrate themselves and enter a spore-like state, hibernating until the next stable era comes. This allows them to bypass some of the extreme conditions and ensures the survival of the species as a whole.

Believe it or not, we have our very own Trisolarans here on Earth. In fact, there's loads of examples, from bacteria to triops, to my favourite of the bunch, Bdelloid Rotifers.

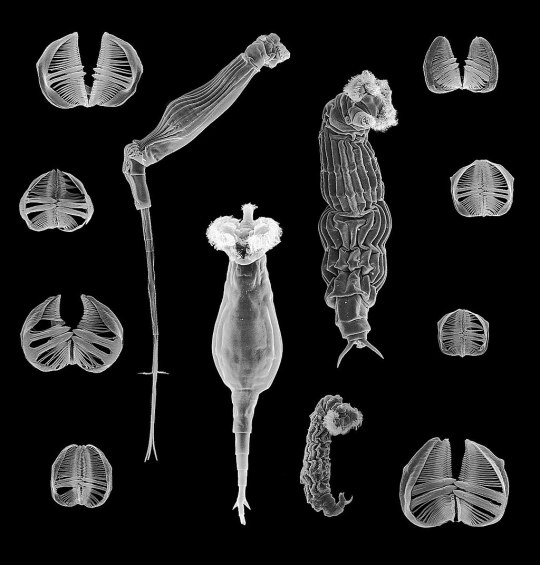

ID: An electron micrograph of some Bdelloid Rotifers and their mouthparts. They are long and slender, with a distinct mouth and tail section. Their mouthparts look like two semicircles lined with a comb-like structure.

These microscopic animals look freaky, because they are. If you've got any media literacy you've probably picked up by now that I am segueing here because they are somewhat similar to the aliens in the Three Body Problem, except this time they are very much real. Like the Trisolarans, Bdelloids live in very ephemeral environments: their usual haunts are the very thin film of water on moss and lichen. As you can imagine, these do not last all that long, and thus when they dry up, so do the Bdelloid Rotifers; in biology, we call this process anhydrobiosis.

"Ok, that's all well and good Ocean Sunfish Hater, but why do you like these guys more than the other anhydrobiotic creatures that roam our good, green Earth?" I hear you ask.

So you know how things that reproduce asexually don't have all that much genetic variation, and how sexual reproduction gives you an edge over asexual populations since you can keep that genetic variation fun and funky fresh, and how that has been the cornerstone for eukaryotic reproduction? Well. Well. Just like me, Bdelloid Rotifers have been completely celibate for 35-40 million years, with some people even bringing that number up to 100 million years, when they diverged from their sister clade. So how do these turbo-virgins not go extinct, racking up tonnes of deleterious mutations, not having any advantageous innovations, and eventually exploding into a genetic soup?

The secret lies in their ability to dehydrate. Not only is it a really handy dandy way to stay alive when your only source of water is gone, it literally rips apart their cells and genes! And why! Why the fuck does that help? It sounds like the opposite of helping!

ID: An electron micrograph of the foot of a Bdelloid Rotifer. It has been shaded a light green. The structure looks almost like a face, with a smile and two stalk-like structures that could be mistaken for eyes. But this is not a face.

Having this mild-to-moderate level of cell membrane and chromosomal damage enables the Bdelloids to take up genetic material from their environment, mostly via their digestive systems, where their last meals are slowly being broken down to reveal that juicy DNA inside. When the water returns and the Bdelloids rehydrate, this genetic material gets incorporated into their chromosomes as their cells get back to work repairing themselves. And they sure ain't picky. In fact, it has been shown that in some species of Bdelloids, up to 8% of their genetic material has non-animal origins. How cool is that?

This is probably what has allowed them to continue adapting and evolving, even when they have been reproducing asexually for so long. This strategy has been so successful that the Bdelloids have managed to diversify into over 450 species. Pretty impressive for a class of animals that haven't had sex in over 40 million years.

Perhaps the Trisolarans might have a similar mechanism as part of their biology (even if they do reproduce sexually as stated in the book). Maybe they've managed to survive for this long because they have been able to absorb useful genes from their home planet, just like Bdelloids have been doing here on Earth. I don't know if these are what Liu Ci Xin had in mind when he wrote the Three Body Problem, but they sure were what I was thinking of when I read the book.

If you're still here, thanks for reading! I know this was a bit of a longer post, but I just wanted to use the new Netflix show to talk about one of my favourite books and one of the weirdest, most underappreciated animals.

#I would like trisolaris because the ocean sunfish would not survive there#bdelloid rotifers are so fucking cool and i think more people need to know about them#biology#ecology#Trisolaris#three body problem

102 notes

·

View notes