#I went from having no social life because my world revolved around my thesis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I don't even have an excuse for not being here my friends have just decided we're doing things every other day

#* ✦ OOC ⁘ are the residents evil sir. )#I went from having no social life because my world revolved around my thesis#to finishing my thesis and having SO MUCH OF A SOCIAL LIFE ALL OF THE TIME#anyways . checking the dash every single day#I am online on mobile I am just not on my actual computer very often if ever#will write when the writing bug hits#but in between that I am definitely lurking lol#telling myself that tumblr is a hobby and its okay if I treat it as such

1 note

·

View note

Text

Charles Burnett

Charles Burnett (; born April 13, 1944) is an American film director, film producer, writer, editor, actor, photographer, and cinematographer. His most popular films include Killer of Sheep (1978), My Brother's Wedding (1983), To Sleep with Anger (1990), The Glass Shield (1994), and Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation (2007). He has been involved in other types of motion pictures including shorts, documentaries, and a TV series.

Called "one of America's very best filmmakers" by the Chicago Tribune and "the nation's least-known great filmmaker and most gifted black director" by The New York Times, Burnett has had a long, diverse career.

Background

Charles Burnett was born on April 13, 1944, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, to a nurse's aide and a military father. According to a DNA analysis, he is mainly descended from people from Sierra Leone.In 1947, Charles's family moved to Watts, a largely black neighborhood in South Los Angeles. Burnett was interested in expressing himself through art from a young age, but the economic pressure to maintain a stable job kept him from pursuing film or art in college.

Influence of Watts

Watts had a significant effect on Burnett's life and work. The community, which gained notoriety in 1965 when violent riots in the area caused the deaths of 34 people and injured more than 1,000, again made the news in 1992 when protestors turned to looting and arson following the acquittal of police officers tried for the beating of Rodney King. Burnett has said that the neighborhood had a strong Southern influence due to the large number of Southerners living in the area. Watts strongly influences his movies' subject matter, which often revolves around southern folklore mixed with modern themes. His film Killer of Sheep was set in Watts.

College

Burnett first enrolled at Los Angeles City College to study electronics in preparation for a career as an electrician. Dissatisfied, he took a writing class and decided that his earlier artistic ambitions needed to be explored and tested. He went on to earn a BA in writing and languages at the University of California, Los Angeles.

UCLA Film School and the Black Independent Movement

Burnett continued his education at the UCLA film school, earning a Master of Fine Arts degree in theater arts and film. His experiences at UCLA had a profound influence on his work, and the students and faculty he worked with became his mentors and friends. Some fellow students include filmmaking greats like Larry Clark, Julie Dash, Haile Gerima, and Billy Woodberry. The students' involvement in each other's films is highlighted by Burnett's work as a cinematographer for Haile Gerima's 1979 movie Bush Mama, as a crew member for Julie Dash's 1982 Illusions, and as a writer and cameraman for Billy Woodberry's Bless Their Little Hearts. His professors Elyseo Taylor, who created the department of Ethno-Communications, and Basil Wright, a British documentarian, also had a significant influence on his work. The turbulent social events of 1967 and 1968 were vital in establishing the UCLA filmmaking movement known as the "Black Independent Movement”, in which Burnett was highly involved. The films of this group of African and African American filmmakers had strong relevance to the politics and culture of the 1960s, yet stayed true to the history of their people. Their characters shifted from the middle class to the working class to highlight the tension caused by class conflict within African American families. The independent writers and directors strayed away from the mainstream and won critical approval for remaining faithful to African American history. Another accomplishment of the Black Independent Movement and Burnett was the creation of the Third World Film Club. The club joined with other organizations in a successful campaign to break the American boycott banning all forms of cultural exchange with Cuba. Many critics have compared the films of the Black Independent Movement to Italian neorealist films of the 1940s, Third World Cinema films of the late 1960s and 1970s, and the 1990s Iranian New Wave. At the time the movement flourished, many countries in the Third World were involved in a struggle for revolution, inspiring them to create films expressing their own indigenous views of their history and culture. In addition to staying true to history, many Black Independent Movement films have been considered a response to the White Hollywood and Blaxploitation films that were popular at the time.

Early career

Charles Burnett's earliest works include his UCLA student films made with friends, Several Friends (1969) and The Horse (1973), in which he was the director, producer, and editor.

Major films

Killer of Sheep (1978)

Burnett's first full-length feature film, Killer of Sheep, was his UCLA master's thesis. It took Burnett five years to finish, apparently due to the imprisonment of one of the film's actors, and was released to the public in 1978. The cast consisted mainly of his friends and film colleagues and it was filmed primarily with a handheld camera, seemingly in documentary style. The main character was played by Henry G. Sanders, a Vietnam veteran who had studied cinema at Los Angeles City College and was enrolled in several classes at UCLA. Sanders went on to a career in films and TV, including roles in Rocky Balboa, ER, Miami Vice, and The West Wing. The lead female character in Killer of Sheep was played by Kaycee Moore, who went on to act in former UCLA classmate Julie Dash's film Daughters of the Dust. The story follows the protagonist Stan, a slaughterhouse worker, who struggles to make enough money to support his family. According to the film's website, the movie “offers no solutions; it merely presents life”. Killer of Sheep revolves around rituals, in the family, childhood, oppression, and resistance to oppression. The soundtrack of ballads, jazz, and blues includes artists Faye Adams, Dinah Washington, Gershwin, Rachmaninov, Paul Robeson, and Earth Wind & Fire. The film was only screened occasionally because of its poor 16mm print quality and failed to find widespread distribution due to the cost and complexity of securing music rights. It was restored by the UCLA Film & Television archive in a new 35mm print of much higher quality. The re-released film won an array of awards including the critics' award at the Berlin International Film Festival, first place at the Sundance Film Festival in the 1980s, then called the USA Film Festival, and a Special Critics' Award from the 2007 New York Film Critics Circle. It was an inductee of the 1990 National Film Registry list. In addition, it was chosen as one of the 100 Essential Films of All Time by the National Society of Film Critics in 2002. Burnett was awarded a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in 1981, following the film's completion.

My Brother's Wedding (1983)

Burnett served as the director, producer, director of photography, and screenwriter for My Brother's Wedding. My Brother's Wedding was his second full-length film, but was not released because of a mixed review in The New York Times after playing at the New Directors/New Films Festival in 1983. As in Killer of Sheep, many of the film's actors were amateurs, including the costume designer's wife. The role of Pierce Mundy, the protagonist, was played by Everett Silas. Mundy struggles to choose between his brother's middle-class existence and his best friend's working-class world. The movie was the first feature Burnett shot on 35mm color film. Its cost was estimated at $80,000. The movie was acquired by Milestone Films, restored by the Pacific Film Archive at the University of California, Berkeley, and digitally reedited by Burnett.

To Sleep with Anger (1990)

To Sleep with Anger was Burnett's first higher-budget film, with an estimated cost of $1.4 million. The grant he received from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation helped Burnett support his family while working on the film. The $250,000 grant spread over the course of five years is awarded to gifted individuals to pursue personal projects. The movie was set in South Central LA and followed the same themes of family and southern folklore as most of his films. The story concerns a lower middle class Los Angeles family that welcomes a guest from the South who overstays his welcome and causes a major disturbance in the family. The family's instability seems to reflect the larger community's volatility. To Sleep with Anger was Burnett's first film to feature professional actors. The lead actors include Danny Glover, Paul Butler, Mary Alice, Carl Lumbly, and Vonetta McGee. Glover, who plays Harry Mention, agreed to a reduced fee and went on to invest in the production. A box-office favorite known for his role in the Lethal Weapon films, Glover continued to star in many successful productions including The Royal Tenenbaums, Dreamgirls, 2012, and Death at a Funeral. Although highly acclaimed by critics, To Sleep with Anger did poorly at the box office. Burnett attributes this to poor distribution and lack of good taste. The film won many awards, including best screenplay from the National Society of Film Critics (the first award of its kind given to an African American writer). Other awards include two Independent Spirit Awards for Best Director and Best Screenplay, the American Film Institute's Maya Deren Award, the Special Jury Recognition Award at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, a Special Award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and nominations for Burnett and Glover by the New York Film Critics Association.

The Glass Shield (1994)

The Glass Shield follows a story of corruption and racism in the Los Angeles Police Department. It was Burnett's first film catering to a wider audience, featuring Ice Cube, the rap artist, as a man wrongfully convicted of murder. The protagonist of the movie, JJ Johnson, is played by Michael Boatman. The movie's themes include a strong emphasis on the powerlessness of its African American characters and female characters. Johnson's female police officer, the first in the precinct, is forced to deal with sexism both within the police department and on the streets. The officer is played by Lori Petty, who went on to become a director in the 2008 movie The Poker House. The Glass Shield was nominated for a Golden Leopard award at the 1994 Festival del film Locarno. It grossed approximately $3,000,000 in the U.S.

Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation (2007)

Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation follows the story of Namibia's hardships while attempting to win independence from South African rule. The film is based loosely on the memoirs of Namibia's first president, Sam Nujoma, the former leader of the South West Africa People's Organization SWAPO. The script was based on Nujoma's autobiography, Where Others Wavered, and was reported to be a government-commissioned celebration of liberation. Both main actors in the movie, Carl Lumbly and Danny Glover, participated in Burnett's prior films, with Lumbly and Glover both appearing in To Sleep with Anger. The movie was filmed in Namibia and casting was especially difficult because the over 200 speaking parts were mostly given to local Namibians, many of whom had differing dialects. The film was an opening-night selection at the 2008 New York African Film Festival.

Documentaries

Burnett has made many documentaries including America Becoming (1991), Dr. Endesha Ida Mae Holland (1998), Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2003), For Reel? (2003), and Warming by the Devil's Fire (2003) which was part of a TV series called The Blues. America Becoming was a made-for-television documentary financed by the Ford Foundation. The documentary concentrated on ethnic diversity in America, especially the relations between recent immigrants and other racial groups. Dr. Endesha Ida Mae Holland was a short documentary about a civil rights activist, playwright, and professor that fought hard to overcome obstacles caused by racism and injustice. Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property featured Burnett's actor and friend Carl Lumbly. The movie won a Cinematography Award in 2003 from the Long Beach International Film Festival. Warming by the Devil's Fire was an episode for Martin Scorsese's six-part compilation PBS documentary. Burnett worked as a producer for the documentary For Reel?.

Shorts

Burnett was involved in many shorts that include Several Friends (1969), The Horse (1973), When It Rains (1995), Olivia's Story (2000), and Quiet as Kept (2007). When It Rains follows the story about a musician that tries to assist his friend with paying her rent. Quiet as Kept is a story about a relocated family after Hurricane Katrina.

Television films

Charles Burnett has directed many made-for-television movies, including Nightjohn (1996), Oprah Winfrey Presents: The Wedding (1998), Selma, Lord, Selma (1999), Finding Buck McHenry (2000), and Relative Stranger (2009). Nightjohn was adapted from a Gary Paulsen novel, and went on to premiere on the Disney Channel in 1996 to high praise. The story follows an escaped slave who learns to read and returns to his former home to teach others to read and write. Nightjohn was awarded the Vision Award of the NAMIC Vision Awards in 1997 and a Special Citation Award from the National Society of Film Critics in 1998, and was nominated for a Young Artist Award by the Young Artists Awards in 1997. Oprah Winfrey Presents: The Wedding was directed by Burnett, with Oprah Winfrey as an executive producer. Halle Berry and Carl Lumbly star in this drama surrounding the wedding of a wealthy African American woman and a poor white musician. Selma, Lord, Selma, a Disney movie, follows the story of a young girl inspired by Martin Luther King Jr. who decides to join the historic protest march from Selma to Montgomery. Selma, Lord, Selma was nominated for a Humanitas Prize in 1999 and an Image Award from Image Awards in 2000. Finding Buck McHenry is about a young boy who tries to discover whether his baseball coach is a former legend in baseball. Finding Buck McHenry won a Daytime Emmy in 2001, a Silver Award from WorldFest Houston in 2000, and a Young Artists Award in 2001, and was nominated for an Image Award in 2001. Relative Stranger was nominated for an Emmy in 2009, an Image Award in 2010, and a Vision Award from NAMIC Vision Awards in 2010.

Awards

In 1988 Burnett won a MacArthur Fellowship for his work as an independent filmmaker.

Burnett earned the Freedom in Film Award from the First Amendment Center and the Nashville Independent Film Festival. The award was given to Burnett to honor his commitment to presenting cultural and historical content that he felt needed to be discussed, rather than focusing on commercial success. Burnett was honored by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival in 1997. In addition, Burnett was presented grants by the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the J.P. Getty Foundation. The prestigious Howard University's Paul Robeson Award was given to Burnett for achievement in cinema. To honor his achievements, the mayor of Seattle declared February 20, 1997, Charles Burnett Day.

In September 2017 it was announced that Burnett was to receive a Governors Award – known as an "honorary Oscar" – from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Recurring themes

The recurring themes in Charles Burnett's work were primarily history's effect on the structure of family. He also strived to make films about working-class African-Americans that denounced stereotypes and clichés. Burnett has told critics that he makes films that deal with emotions coming out of real problems like maturity and self-identity. He also found a recurring theme in liberation and struggle perhaps after the influence from the UCLA's Third World Film Club that championed the revolutions occurring worldwide in the 1960s and 1970s.

Other projects

In 1999, Burnett directed a film called The Annihilation of Fish. The film is an interracial romance film starring James Earl Jones and Lynn Redgrave that won the Jury Award from the Newport Beach Film Festival in 2001, the Audience Award at the Sarasota Film Festival in 2001, and a Silver Award at WorldFest Houston in 2000. Burnett and two other directors, Barbara Martinez Jitner and Gregory Nava, directed the television series American Family. American Family was nominated for 2 Emmys and a Golden Globe Award and won many other awards. Burnett also acted in the documentary Pierre Rissient: Man of Cinema with Clint Eastwood. He is currently in pre-production on two films projects: The Emir Abd El-Kadir and 83 Days: The Murder of George Stinney.

In January 2019, it was announced that Burnett would direct the film Steal Away, based on Robert Smalls's escape from slavery.

Personal life

Charles Burnett is married to costume designer Gaye Shannon-Burnett. They have two sons, Steven and Jonathan.

Filmography

Several Friends (short, 1969)

The Horse (short, 1973)

Killer of Sheep (1978)

My Brother's Wedding (1983)

To Sleep with Anger (1990)

America Becoming (TV documentary, 1991)

The Glass Shield (1994)

When It Rains (short, 1995)

Nightjohn (television film, 1996)

The Final Insult (docufiction short, 1997)

The Wedding (TV, 1998)

Dr. Endesha Ida Mae Holland (documentary short, 1998)

Selma, Lord, Selma (television film, 1999)

The Annihilation of Fish (1999)

Olivia's Story (short, 2000)

Finding Buck McHenry (television film, 2000)

American Family (TV series, 2002)

Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (TV documentary, 2003)

For Reel? (TV, 2003)

The Blues: Warming by the Devil's Fire (TV documentary, 2003)

Namibia: The Struggle for Liberation (2007)

Quiet as Kept (short, 2007)

Relative Stranger (television film, 2009)

Power to Heal: Medicare and the Civil Rights Revolution (with Daniel Loewenthal, TV documentary, 2018)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writer’s Interview

Tagged by @galadrieljones! Her interview was fascinating and really informative; I would recommend you all check it out.

Tagging forward to @iarollane @charlatron @wardsarefunctioning @aban-asaara @thevikingwoman @athenril-of-kirkwall @fourletterepithet @oops-gingermoment @thunderheadfred @loquaciousquark @obvidalous@barddoc1992 and anyone else who wants to respond!

Q: What is your coffee order?

I don’t drink coffee. Tea for me, please!

Q: What is the coolest thing you’ve ever done?

The first thing that comes to mind is going to Iceland in 2016. Driving all around the island and seeing the fucking glacier lagoon Jökulsárlón was just.... breathtaking. I’ve never seen a place like that in my life.

Maybe another cool thing I did was finally find the balls to do a cosplay (a casual, lazy one, but a cosplay nonetheless) last year when I went to DragonCon in Atlanta.

Q: Who has been your biggest mentor?

Uhh, I don’t have any? But in terms of people who encourage me and help me keep my chin up in those moments of self-doubt (YA’LL KNOW THOSE MOMENTS), I would have to give thanks to @schoute, @viktuuri-fluff-saved-my-life @emileoutofit and @lylypuceonarchive, either for listening to my whining, leaving the most lovely comments and encouraging words, or both!

Q: What has been your most memorable writing project?

Stormbirds and Stalkers, my Aloy/Nil Horizon Zero Dawn fic, was probably the most memorable. I was OBSESSED with writing that thing to the point of putting out a chapter almost every day for the month it took to write. When I hear songs from the playlist I was listening to at the time of writing that fic, it takes me straight back to the feeling of loving that ship so much and being so into the writing that I was ignoring almost everything else (INCLUDING MY EXTREMELY PATIENT FIANCE). To this day, it’s my most popular fic.

In more recent memory, Damned Spot (the Fenris/Rynne Hawke bartender modern AU) is memorable because it has been incredible and inspiring to build the world with @schoute and to collaborate together with the fic and art. I’ve never worked together with someone on a project this way and it’s been so much fun.

Note, also, that I have a Master’s thesis and two published scientific articles under my belt, and those don’t even get an honourable mention in terms of memorable-ness. Fanfic writing defines who I am as a writer.

Q: What does your writing path look like, from the earliest days until now?

Uhh... Well, I guess I wanted to be a storyteller in some sense since I was a kid. I really used to love drawing, and the first thing I ever wanted to be was a comic strip artist. I used to make comic strips for myself from as early as I can remember until I was in high school. They largely revolved around stuff I wanted to happen in my real life (vacations I was looking forward to, boys I had crushes on in high school, etc.). REAL SCINTILLATING STUFF.

In terms of writing specifically, I’ve always been comfortable with writing. It was always just something I could do pretty easily without thinking much about it, but it was never really a creative thing or a thing I saw as a special talent. Friends in high school would ask me to edit their work, and I wrote an essay in grade 11 that a teacher said was “university level”. (I wish I still had that essay, actually. The thesis was that Sigmund Freud was a feminist. He really wasn’t, but I quite successfully argued that he was HAHAHAH.)

In university (undergrad and Master’s degrees), academic writing was just part of the work, so I just did it - again, without thinking much about it. Then I started working full-time and didn’t write anything really except for clinical notes and healthcare stuff for a couple years.

It wasn’t until I started writing fanfic in 2017 that writing became an actual creative process for me and something I recognized as a talent. It became a way that I could actually use my imagination - something I don’t feel like I had done since I was a kid. Fanfic has been the best and only way to express myself creatively; I never considered myself a creative person until I started doing this. So, I mean, I guess I’ve written things to some degree or another throughout my life, but I didn’t see myself as a writer until I started writing fanfic, and now it’s one of the skills I cherish most.

Q: What is your favourite part about writing?

Getting that perfect turn of phrase or dialogue between characters that encapsulates what I’m feeling or imagining for the scene. And when people comment and pick out those things that I was so proud of writing, that is just the cherry on the sundae.

Q: What does a typical day look like for you?

Wake up at 6:50am, eat breakfast, go to work and spend the day wishing I was at home writing. Go home, do a quick yoga session in my living room, WRITE WRITE WRITE until dinnertime which is anywhere between 8-10pm because my fiance and I are both Creative™ and thus Not Adherent To Regular Mealtimes™. Cook (or order in), eat dinner and watch a movie/show with the fiance, WRITE some more depending on the time, shower and bed around 1:30am. Rinse and repeat.

On weekends: wake up around 9-9:30am, yoga, breakfast, WRITE WRITE WRITE WRITE WRITE WRITE, with occasional irregular food breaks and poking around with the fiance to see what he’s up to (he’s a digital artist and filmmaker). Sometime around 8-10pm, cook (or order in), eat dinner and watch a movie/show with the fiance, WRITE some more depending on the time, shower and bed around 2-3am.

If we go out and do something during the day, or if I’m actively playing a video game, then obviously the writing time gets eaten into lol. Oh, I guess we clean sometimes too. Sometimes.

Q: What does your writing process look like?

I like to outline before I start a longfic; I like to know all the main points of the story and how it’s going to end before I get started. For individual chapters or oneshots, I also tend to outline the main points or main pieces of dialogue before getting into the meat of writing the chapter.

I listen to music CONSTANTLY. I actually can’t think unless there is music playing. I have playlists for all my ships. I often will pick one song that illustrates the feel of the chapter and listen to it on loop until the chapter is done.

Q: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten?

I’ve never really gotten any advice, so I’m going to paraphrase @galadrieljones‘ advice, since I naturally follow it and find it to be totally true: “Stay in the room. Once you’ve made the decision to write, don’t leave the room. If you leave the room, you’ll lose your momentum.” This is also the idea behind writing sprints - to force yourself to do nothing else but write for a set period of time, just to get those words out and stay in the moment of the writing. Yes, this might sometime mean I have spent 6 straight hours writing with only bathroom breaks, but those are often the days when I stop and feel like I’M THE MOST AMAZING HUMAN BEING IN THE WORLD because I got the damned chapter done.

Q: What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned?

Similar to @galadrieljones‘ response, I would say that the most important thing for me has been to keep the writing for the pleasure of it and not to monetize it. I have been asked before if I would consider writing fiction professionally, and my answer is a resounding ‘no’. If I wrote professionally, I couldn’t write exactly what I want to write on my own timeline, and I wouldn’t be able to share it immediately and garner the kinds of interactions and socializing with my readers that I really enjoy. Fanfic is the perfect medium that lets me write exactly what I want and to hang out with fun like-minded people while doing so.

Q: What advice would you give someone who wants to start writing?

DO IT! DO IT DO IT DO IT!! I have so many friends who have said they want to write and don’t have the time or think they would be shitty at it - and I always say to JUST DO IT!! This also calls back also to some of the questions from earlier: if you really want to write, you may have to carve out time for it. MAKE time for it if it’s something you really want to do. Force yourself to find an hour or two and to fill it with writing instead of some other activity. If you really want to do it, you can and will find time for it.

#tag meme#tumblr game#fanfic writer's life#thank you for the tag!#this was a fun one to fill out!#pikapeppa reflects#ask me anything

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Arnold!, and why it’s still important today

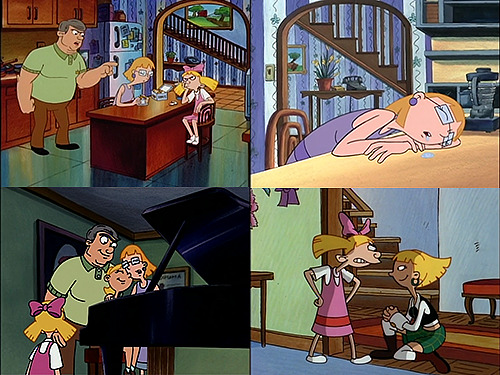

Less than a year ago my fiancee and I took to rewatching Hey Arnold! for the first time in YEARS to prep for The Jungle Movie. Having been obsessed with it when I was a kid, I knew the show like the back of my hand, so I went through and made a “best of” list of episodes, and we watched those.

Aaaand immediately went back to the beginning and watched ALL of them.

AAAAND went back AGAIN because revisiting this show has been so fun for me, and it just puts me in a good, good place. Since this (eternal) marathon began, I’ve wanted to do a big ol’ overview of the show itself, and why it’s important. It’s very diverse, and from a time when that really wasn’t what kids’ shows were striving for like they are today. There are tons of characters of color, different religions, sexualities, social classes, etc, and I kind of need this show to get the love and attention it so deserves. It’s really kinda gone unloved for a long while now (which is understandable, it’s been off the air since 2002), and I just know it’d be a huge deal if more people knew/remembered how inclusive it was. I’m kicking myself for not writing this sooner, but I’m holding out hope for Nick to greenlight a new series, and my dearest wish is that I can remind people of this wonderful, thoughtful show, and get it the attention it deserves.

Hey Arnold! is FULL of amazing characters and stories, so BUCKLE UP BUTTERCUP, THIS GON’ BE A LONG ONE.

| City life, poverty, & crime |

At it’s core, Hey Arnold! is a show about inner city kids, their school, and how they go about their daily lives. I did some research for this (believe it or not lmao), and besides Sesame Street, there is no other media geared toward kids that touch on this. That’s insane to me. And while Sesame Street is fantastic, it tends to steer on the positive side of city life. Which is great!! However, Hey Arnold!, being written for an older audience, isn’t afraid to show the not-so-pretty side of things as well. Violence, crime, theft, pollution, and poverty are ALL covered in more than just a few episodes. We saw a lot of this right off the bat in the first episode, “Downtown as Fruits”.

As for violence, in the episode “Mugged”, Arnold is jumped on his way home one evening, and takes self defense lessons from his Grandma.

And it’s not the last time Arnold, or other characters are mugged. It’s just something they deal with, something they have to learn to protect themselves from. And sometimes, they can’t.

They don’t shy away from poverty within the city, either. Multiple characters are shown to be very poor, and with the exception of two episodes in the whole series (Lila in her debut episode, “Ms. Perfect”, and Sid when he wants to impress a rich classmate and is too embarrassed to have him over at his own home, “Arnold’s Room”), it’s never really shown as a bad thing, or even as a defining character trait. It just is.

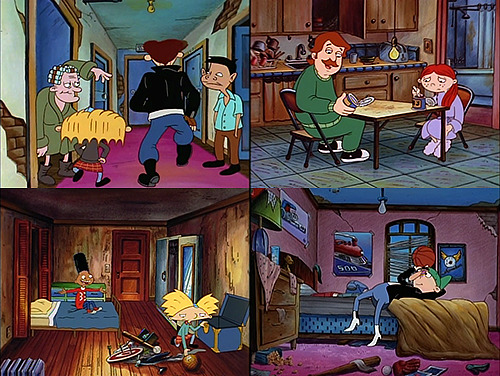

Even our title character lives in a boarding house run by his grandparents, inhabited by tenants of very little means. The building itself is always needing repairs, the tenants almost never have their rent on time, and they really don’t shy away from how dingy some of the rooms are there (pictured above, bottom left).

But again, all of this just is. It’s never portrayed as a bad thing, and none of the kids care much about it. Of course there’s Rhonda, the snooty, rich girl stereotype, but even she has a handful of episodes where she grows as a character and is repeatedly called out for having a classist attitude. In the end, all of these kids care about each other and never give a second’s thought to each others’ social class.

| Diversity & inclusiveness |

I’m putting the rest under a read more cut so no one murders me for clogging up their dashboards :’)

One of the most wonderful things about this show is how diverse the cast of characters is. Especially being that in the 90′s, it wasn’t something shows were expected to have, but they did it here anyway.

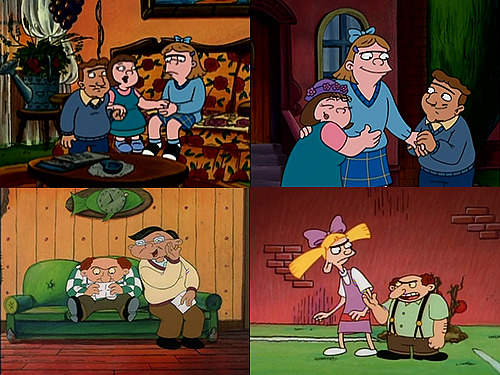

Our primary character of color is, of course, Gerald Johanssen, Arnold’s best friend and all-around cool dude. He’s the star of a good amount of episodes, and even when one focuses on Arnold, he’s almost always right there next to him. With Gerald comes his family as well, consisting of a little sister, older brother, his mom who cashiers at a corner store, and his father who’s a businessman and Vietnam veteran, ALL OF WHOM have distinct personalities and stories, and the lot of them are portrayed just like any other family on tv.

Next would be Phoebe Heyerdahl, the soft-spoken smartest girl in class, and Helga’s best friend. She’s half Japanese on her father’s side, and if you pay attention, her and Gerald have a thing going on, which is sO freaking cute.

Phoebe is also super important because she’s the only person in the show who really knows and understands Helga. She’s always there to support her, listen to her, and guide her when she can. However, Phoebe does have a handful of episodes to herself, and we even touch on how being the over-achiever in class isn’t always a good thing, and can be damaging to children if they feel like they need to be the best. It’s a super important lesson for kids to learn.

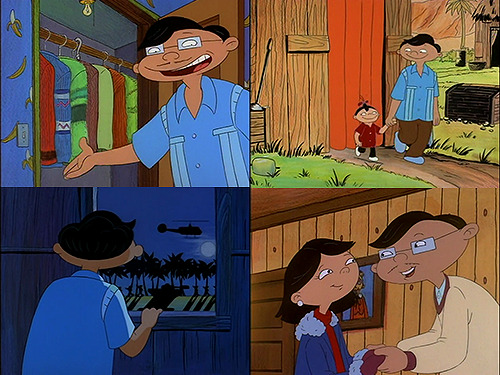

If I gave a paragraph to EVERY single character of color in this show we’d literally be here all day, so I’m gonna finish off with my personal favorite, Mr. Hyunh. A middle-aged Vietnamese man who resides in Arnold’s boarding house, Mr. Hyunh is one of the best adult characters in the show. In fact, one of the. single. best. episodes of the entire show, “Arnold’s Christmas” revolves entirely around him, and how he was separated from his only daughter during the Vietnam War. Holy shit, right? I could go on and on about that episode on its own (there’s a reason why it’s one of the most well known episodes), but I’ll put a cap on it there. Mr. Hyunh has the starring role in a number of other episodes, and he’s always great. He’s funny, cares deeply about Arnold and the other boarders, and is genuinely happy where he is.

But do we stop at diversity where race is concerned? NOPE. This is a show for literally everyone. Gosh, it’s hard just to even figure out where to start.

How about Harold? He’s not only Jewish, but there’s an entire episode it, (”Harold’s Bar Mitzvah”), and he’s shown to be very close with his mentor, Rabbi Goldberg.

We have three characters with dwarfism. Ernie Potts, a boarder at the Sunset Arms, and Big Patty’s mother and father. How freaking cool, right? Patty’s parents are scarce in the show, unfortunately, but are extremely caring and supportive of their daughter. And yet again, it’s never brought up, it’s not a defining trait, it’s not a big deal. They’re just regular people.

As far as LGBTQ representation, a little while after the show was cancelled, show creator Craig Bartlett revealed that the kids’ school teacher, Mr. Simmons, is gay. In “Arnold’s Thanksgiving”, we see his partner, Peter, and we see the two of them together in “The Jungle Movie” as well. And, though not explicitly shown onscreen, Craig has said that Eugene Horowitz, an overly optimistic classmate of Arnold’s, is gay as well.

| Helga Pataki, abusive households & mental health |

You may have noticed that I’ve gone this entire thing without breaking down sobbing about Helga. Ohh, don’t you worry, we’re almost there!

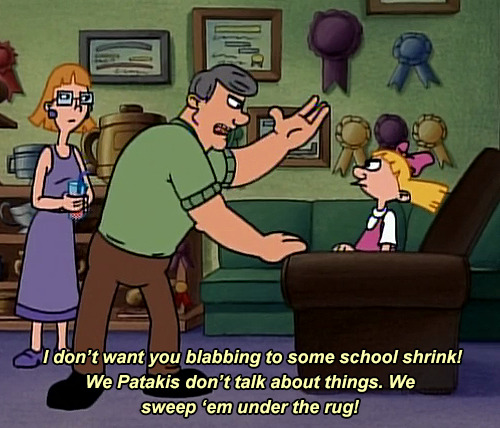

I could be wrong, but I think one of the most well remembered aspects of this show, even by people who haven’t seen it in years, is that Helga’s family is really messed up. Her mother, Miriam, is always passed out drunk on the kitchen counter or behind the sofa, and her father, Big Bob, is always calling her by the wrong name and forgets she even exists most of the time. Then of course there’s Olga, her “perfect” older sister who means well, and cares about Helga more than their parents do, but ultimately cares more about her self image.

Sure, each of them get a few episodes where they get called out on their behavior and they (kinda) redeem themselves, but at the end of the day, they’re always right back at it. If I had a talent for it, I could SERIOUSLY write an entire thesis on Helga’s family’s dynamic in this show, but I’m going to (try to) keep it brief.

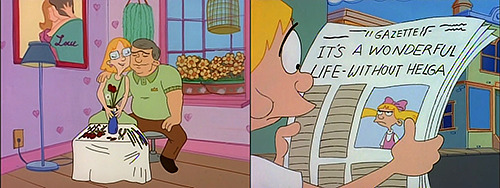

The Pataki household is a very real, very poignant depiction of emotional and mental abuse that we just do not see in cartoons, or anything geared towards a younger audience. Like I said, we have the odd episode or two where Helga will bond with one or both of her parents or her sister, but things never truly “get better”. Given the significant age gap between her and Olga (who’s in college while Helga is in the 4th grade), it’s suggested that Helga was probably an accident, and the catalyst of her parents’ unhappiness. In “Magic Show”, Helga goes through an “It’s A Wonderful Life”-type dream sequence, but backwards. Arnold makes her disappear forever in a magic trick, and the entire world is better off without her, including her parents, who are happy, fulfilled, and affectionate with each other. IT’S REALLY MESSED UP, GUYS.

And this, ALL of this, is one of two reasons why her crush on Arnold works. In a lesser show, Helga’s obsession with Arnold would be creepy, and her dependence on him would be a weakness to her character. However, we eventually find out that where her family failed her at every turn, Arnold was the first one to not only notice her, but show her kindness.

And in the end, no matter how much she teases him and bugs the shit out of him (which are just defense mechanisms to begin with), she always, always puts him first. Every single chance she gets, she does the right thing for him. Helga’s feelings for Arnold work so well because she truly cares for him. Of course her closet shrine and dozens of books of poetry are over the top, but so is Helga. She’s loud, abrasive, crude, but above all else, she’s fiercely loyal, passionate, and intelligent. And, more than anything, she just wants Arnold to be happy. That’s real love, folks.

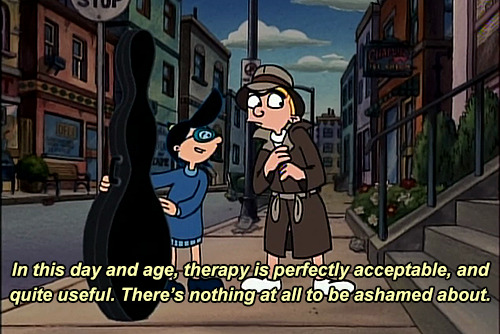

My personal favorite episode of the entire show is “Helga On the Couch”, where Helga goes to see a psychologist due to her abrasive behavior. This episode is so so so important, you guys. It was really the first piece of media I saw as a kid that not only explained what therapy even was, but painted it in an extremely positive light. At first, Helga is mortified to have to go, and her parents don’t help the situation at all. Not only do they disapprove, but Big Bob is angry with her for being selected for therapy. He says that it’s embarrassing, and actually warns Helga not to tell the psychologist anything that might out them as abusive.

However, Phoebe assures Helga that therapy is not only good, but perfectly normal, even for kids their age.

And throughout the session, Helga opens up about her family, why she’s so defensive, how she feels about Arnold and why, and feels so much better at the end of the episode. I hate that the show had to end after this season because I would die for more episodes about Helga and her sessions with Dr. Bliss.

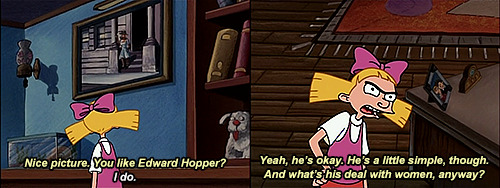

Not to mention we get one of the best bits of dialogue in the entire series omfg:

Again, this is SUPER IMPORTANT for kids to see. This episode told us that mental health is JUST as crucial as physical health, and took every bad opinion about therapy and stuck a boot in its ass. It’s GOOD, it’s NORMAL. I can’t say enough about how much this episode meant to me as a kid, and still means to me today.

I seriously have to stop myself from going on for 500 years about Helga and why she’s not only the best character on the show by a fuckin’ landslide, but one of the THE best female characters in anything. Ever. I think I’m going to put a pin in that, and hopefully get to writing a post just about her. The point is, she is an exceptionally written character, and super important for kids to see, to be able to relate to. She’s heavily flawed, but is infinitely loyal for those she cares about. She’s extremely complex, hilarious, interesting, and deeply sympathetic. I LOVE HELGA PATAKI SO MUCH DON’T TOUCH ME, GOD.

| Criticisms & wrap-up |

I’m gonna try and end this here before it turns into a novel, but there is still SO MUCH going on in this show that I could talk about. If anyone wants to add to this post, please do!! I honestly just need to end this sometime lmaoo.

Now, the show isn’t perfect. Rewatching it in our current social climate turned up a (notedly small) few problematic things. Mostly fat jokes about Harold, and some of the boys will tease the girls, saying they can’t do certain things bc they’re girls, etc. Normally these are small, throwaway lines, but they’re still there, and stand out nowadays. Just a warning!

The only other criticism I have for the show as a whole is actually the entire plot line with Arnold’s parents, “The Journal”, and most of “The Jungle Movie”. Now, don’t get me wrong, I do enjoy it, I think there’s enough heart and depth to make up for, well, how fuckin’ silly it is, but it’s still just that. Silly. This show that spent five full seasons in an urban setting, dealing with very real characters and situations, suddenly veered off into heavy fantasy. It’s jarring, and a little weird. We find out not only that Arnold’s parents were basically Indiana Jones and Lara Croft, but also Arnold was a miracle baby whos birth silenced an erupting volcano, and now he’s seen as some “chosen one” to entire tribe of people living in the jungles of South America.

LMAO WHAT.

No, it’s kind of insane. I think I personally don’t mind it so much because I have a lasting fondness for it from when I was a kid, and like I said, it does have a lot of heart behind it, but it’s very apparent as an adult how ridiculous it is. However, in the show’s defense, its always had episodes about ghosts and all matter of supernatural creatures that just exist and are real in this universe, so it’s not totally out of left field. It’s just odd to have it at the forefront, and I can understand if people don’t care for it.

BUT! The show, at its heart, has always been about kids, their families, and the city they live in. I know if the show was brought back, that’s what they’d get back to.

Also, it’s kind of hilarious if you think about it this way; Arnold is BASICALLY a magical girl who’s super power is solving everyone else’s problems. That’s the show.

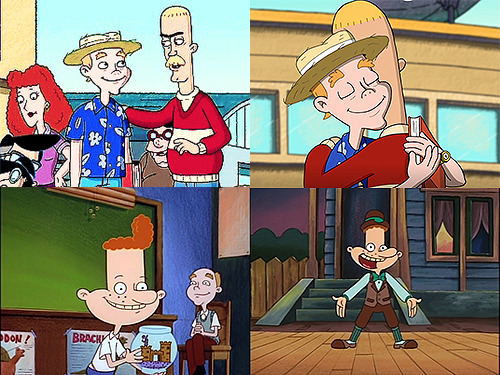

And holy cow, speaking of Arnold, I haven’t talked about him at all. SHIT. UH, real quick. Arnold is a good, good, good, gOOD, GOOD BOY. To be extremely honest, Arnold would be boring as hell in a lesser show. He really doesn’t have many flaws, he’s always doing The Right Thing(TM), he’s always optimistic... you get it. But somehow, miraculously, he’s still interesting and fun to watch. He’s just so goddamn good. Like, cinnamon roll levels of good. And he does fuck up once in a great while, but of course, learns from it. He’s definitely your standard male, pre-teen, main character in a world where we have way too many of those, but he’s just so pure that you can’t help but love him.

He honestly works best as a counterpart to Helga, which we tragically get so little of in the show (and why we need a new series dear god Nickelodeon PLEASE), but that’s a whoooole other post for me to write.

Goddamn okay, I’m wrapping it up. If you haven’t noticed by now, this show means a lot to me. It really touched me as a kid, it was my first fandom before I even knew what fandom was, and revisiting it has been so fun. It’s honestly been helping me get through an extremely rough patch in my life right now. The show more holds up after all these years, and I think it’s even more important now than it ever was. We need more shows like this.

If you’re interested, the entire series is on Hulu!

#hey arnold#nickelodeon#diversity#mental health#long post#DEAR GOD THIS TOOK TWO DAYS TO PUT TOGETHER#pls read i am begging :')#also I have zero writing talent so this is just me babbling#it's not meant to be like an actual essay or anything#just me shouting with visual references#LONG POST DID I MENTION

866 notes

·

View notes

Text

2017 in review, at last.

It's been awhile since I logged out and never logged back in to this blog. The first and foremost reason was that I was really trying to get myself focused on academic matters, such as my thesis, and... Well, only my thesis basically. The particular thing around which my life currently revolves. Secondly, I had to be honest that: I just had nothing good to write about. Something that I was very shameful to admit about, but feels like I want to just purposely profess right now. Because I really, really want to write something (that people could actually read as well) at the moment, and if the only materials I had in my mind are not so good ones, so be it.

But let me try to shape it in a more uplifting tone, rather than an utter downfall.

It's going to be a review about 2017. The year that seems to be very much likely will be remembered about the most by myself, despite myself already knowing that I really do not want to remember the majority part of it. I really don't. It's one heck of a scary year, where things that I could never imagine happened to me actually do happen (in both good and not-so-good ways), and I lost control, and I had to struggle more than ever to grip back onto anything. And many other terrible, awful details that I'm very much thankful to be over (not necessarily bigger picture-wise over, but at least those smaller sequences ended). Most people don't know about it, and I would very much rather they stay that way, but somehow I end up typing this post knowing that the opposite would happen. See, my brain is a complicated logic machine indeed. But I'll try to stay in a lane where people who read this, like you, could actually learn something from what I experienced, and the last thing you would do is maybe empathizing me.

I started off 2017 coming back from one of the most remarkable trips I've ever had in my life (but that was before I went here and there). Nevertheless, instead of feeling happy and energized coming back to my residence in Edmonton, I felt more homesick than ever. The feelings of spending time with people you do like and make you feel that you do belong in their circle remind me of the comfort of home, something I was craving too much for. Something that I just realized, that I might not find here in this city. I could write an entire essay explaining my feelings and situations regarding that particular situation, (in fact I did, but I then cut-pasted all the texts into another (upcoming) post,) so I would just be brief here.

At the same time, a couple closest friends of mine happened to drift away as well because of some reasons that I couldn't explain here either. Hint: it involves some of them finding a new society which I clearly can never fit in any way possible even if I want to, some of them changing into the kind of people they never were before and it also falls into the same category of the previous group, and some of them finding... love. My mistake was probably that I stayed the same while everyone else changed, but I just couldn't change into what they have become. Long story short, that was the end of our previously-meaningful friendships. And just like that, it was the first time in my entire life that I thought that it's not worth it to chase those people. It was the first time in my life I let friends go, and decided not to stick around anymore. It was the time I broke the lifetime record of me keeping close to everyone that I was once close with. And no, it didn't feel good at all, it still does not, although maybe necessary.

The same time they occurred, I started discovering new phase of difficulty in my academic phase. I had the firsthand experience of a rather discriminating story, where people believed that I was really incapable of something that I had to gain a credit for. And I fought back, in a way where I tried not to hurt them back, because I knew I was capable of doing that, although I failed in convincing them initially. And it was the first time I cried uncontrollably in the middle of the night that I had to knock on my neighbor's door to disturb their sleep just because I was literally losing my mind at that moment. Just thinking that people could let you down that way is just... terrifying. But thankfully, I crawled back, I pushed back, and eventually I got what I knew I deserved to have. Wasn't easy at all, but the fight was worth every teardrop.

And along the Winter term 2017, I filled my days going to social gatherings, signing up for new clubs and volunteering activities, for the sake of looking for a new circle where I could fit in. All by myself, hoping that the casual conversation I tried to build with people in the room was going to lead me to a new lasting friendship with anybody on campus. Spoiler alert: never found it even until today, lol. Although, I did meet two early-20's Indonesian ladies that I clicked with and surely we immediately became friends. Kudos to Chacha and Suzi for saving me during those hardship. Also, I finally began to attend the Indonesian Muslim community's halaqah, and even though 90% of them were adults with the other 9% being babies and toddlers, at least I was happy to find people that speak my mother language again.

Springtime was when I began to gather my thesis data. I had an accident where suddenly, all the money that I had in my bank account was literally stolen and left zero and it took a week for the bank to process and recover all my savings. I was just arriving in Calgary at the time to do my thesis work, about to pay for hotel room rent when I realized that I had nothing in my savings and my credit card didn't even have enough balance. So all I could do was for sure, crying on the phone. Thankfully, an Indonesian family that I know in Edmonton was able to help me out by lending me some money to cover the hotel rent. That day was when I realized that I missed home way too much, because my family kept calling me to check if the situation got better, and they also sent me money rightaway to cover the loss temporarily. Needless to say, I then cried even more crazily because of how homesick I had been, and how I had realized that I had the best family in the world I would never replace even with the Kardashians (well, of course).

However, of course the feeling of social inclusion didn't stop there, because when I spent 1.5 months in Calgary, I had nobody around. I was just working with my cores, on my table, every single day. I was just too shy to talk to strangers across the table (who might be some gentlemen from a huge O&G company... Well if I were socially more extraverted I could've networked and been less stressed at the same time!), so I was just by myself all the time. But can you imagine though, being the only hijabi, with legit Asian face, brown skin, and short body, among all those Caucasian people? I mean, do you not know how terrifying it was?

But then, Summertime was the happiest time of the year, because, heck yeah, it's flippin' summer! Sunshine's in the air! That's already one good reason. But other than that, I also got lucky to be able to get one of the VIA Canada 150 pass, where basically I got a pass to travel to anywhere in Canada by VIA Rail train for the whole month of July of only 150$. Isn't that the best thing in the world? (jk, I've come to realize that the best thing in the world is the presence of family and loved ones :).) So of course, that's what I did. Traveling across southern border of Canada, coast to coast, for 38 days.

And I thought life's going to get better. I might have been wrong though.

In the Fall, I realized that I missed home way too much. All the accumulating ache I've felt since the beginning of the year is on a new level. I thought I'd become numb after some time, that I'd finally be okay with having no meaningful relationships with fellow human beings and just learn to be a lone wolf because none of my effort to change the situation seems to work, that I'd be overwhelmed with work and forget to miss home at last. Well, I was wrong. Having no more classes, only thesis, basically means that I now have more flexibility and freedom, in terms of work schedule, as well as social life. I no longer meet people in regular basis, because I was technically almost always the only person working in the office room (some people choose to work in their labs, I do not, just because the room setting). And after it went after some time, the bad thoughts after subconsciously constantly isolating myself finally caught me. All that I can confess is that it's the worst, scariest, most intense, most aggravating feeling I've ever experienced.

At some point, I realized I have become the worst version of myself that I never was before. I lost track on my responsibilities, I disappointed myself and other people related to my work a couple times although thankfully it wasn't something too major, but it made me even sadder than before. All the homesickness and alienation I've felt for the entire year, I thought I could still handle them because at least it didn't seem to affect my academic performance... Yet. But this time, it became real.

But He is good. He gave me the chance to feel happy for a bit. I was able to do one my lifetime dreams to solo travel to Peru. (Wasn't something I was going to do if not because I booked the ticket back in Winter, though.) It was a week where I was reminded how nice it feels to be able to the person that we know we are, that radiate positive energy into things that we choose to do, and just to be able to be the best version of yourself, amidst the overall tough situation that we're in. I made new foreign friends, stayed at a friend's friend's place which made me regret, "Why haven't we been friends since you were still at the U of A?!" and most of all, I became that bold, brave, fearless person that I always knew I could've become. And maybe... It's just a matter of time until I get to discover that side of me here, in Edmonton.

Nevertheless, after I came back, the pain became real again. I became familiar with counselling services, and many articles or videos regarding self-help, mental health, self isolation and/or inclusion, and so forth. Although, I was, and I am grateful for that as well, for it made me able to sit back and think about who I really was, what I want to become, what things actually matter to me, and make me want to build a closer, more meaningful relationship with my creator.

The pain still lingers, but I know I'm not alone. I am grateful that I, at least, have never had any thoughts about harming myself, because imagining the pain that my loved ones will have to go through to see me suffer even more is just... Unbearable. I can't handle that much of pain. And thinking about gratitude, I think I'd like to close this post with things that I'm thankful for in 2017, despite all the distress that I constantly mentioned about:

That I still have a supportive family, and I realize how much they mean to me, and how much I've taken them for granted all these years,

That I also have a supportive boyfriend and we're going through our fifth year together. That he's doing well with his studies in the Netherlands, and while many people around our age might still have insecurities about marriage and seeking for future spouse and everything, we might not have to worry about that,

That I still get to maintain my friendship with my best friends back home, and that they seem to be going through a good, deserving life,

All my traveling opportunities,

That I have the willingness to be a better servant for my creator, that my pain makes me feel that I want and I try to get closer to Him, that the only thing I want to do in 2018 (other than getting that MSc degree and reuniting with my loved ones) is becoming a better servant for Him.

Well, January 2018 clearly wasn't a turning point for the dark maze I was journeying into in 2017, but maybe we could try in February?

0 notes

Link

(Via: Hacker News)

Sapiens and Collective Fictions

Recently I read Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Harari. The basic thesis of the book is that humans require ‘collective fictions’ so that we can collaborate in larger numbers than the 150 or so our brains are big enough to cope with by default. Collective fictions are things that don’t describe solid objects in the real world we can see and touch. Things like religions, nationalism, liberal democracy, or Popperian falsifiability in science. Things that don’t exist, but when we act like they do, we easily forget that they don’t.

Collective Fictions in IT – Waterfall

This got me thinking about some of the things that bother me today about the world of software engineering. When I started in software 20 years ago, God was waterfall. I joined a consultancy (ca. 400 people) that wrote very long specs which were honed to within an inch of their life, down to the individual Java classes and attributes. These specs were submitted to the customer (God knows what they made of it), who signed it off. This was then built, delivered, and monies were received soon after. Life was simpler then and everyone was happy.

Except there were gaps in the story – customers complained that the spec didn’t match the delivery, and often the product delivered would not match the spec, as ‘things’ changed while the project went on. In other words, the waterfall process was a ‘collective fiction’ that gave us enough stability and coherence to collaborate, get something out of the door, and get paid.

This consultancy went out of business soon after I joined. No conclusions can be drawn from this.

Collective Fictions in IT – Startups ca. 2000

I got a job at another software development company that had a niche with lots of work in the pipe. I was employee #39. There was no waterfall. In fact, there was nothing in the way of methodology I could see at all. Specs were agreed with a phone call. Design, prototype and build were indistinguishable. In fact it felt like total chaos; it was against all of the precepts of my training. There was more work than we could handle, and we got on with it.

The fact was, we were small enough not to need a collective fiction we had to name. Relationships and facts could be kept in our heads, and if you needed help, you literally called out to the room. The tone was like this, basically:

Of course there were collective fictions, we just didn’t name them:

We will never have a mission statement

We don’t need HR or corporate communications, we have the pub (tough luck if you have a family)

We only hire the best

We got slightly bigger, and customers started asking us what our software methodology was. We guessed it wasn’t acceptable to say ‘we just write the code’ (legend had it our C-based application server – still in use and blazingly fast – was written before my time in a fit of pique with a stash of amphetamines over a weekend. It’s still in use.)

Turns out there was this thing called ‘Rapid Application Development’ that emphasized prototyping. We told customers we did RAD, and they seemed happy, as it was A Thing. It sounded to me like ‘hacking’, but to be honest I’m not sure anyone among us really properly understood it or read up on it.

As a collective fiction it worked, because it kept customers off our backs while we wrote the software.

Soon we doubled in size, moved out of our cramped little office into a much bigger one with bigger desks, and multiple floors. You couldn’t shout out your question to the room anymore. Teams got bigger, and these things called ‘project managers’ started appearing everywhere talking about ‘specs’ and ‘requirements gathering’. We tried and failed to rewrite our entire platform from scratch.

Yes, we were back to waterfall again, but this time the working cycles were faster and smaller, and the same problems of changing requirements and disputes with customers as before. So was it waterfall? We didn’t really know.

Collective Fictions in IT – Agile

I started hearing the word ‘Agile’ about 2003. Again, I don’t think I properly read up on it… ever, actually. I got snippets here and there from various websites I visited and occasionally from customers or evangelists that talked about it. When I quizzed people who claimed to know about it their explanations almost invariably lost coherence quickly. The few that really had read up on it seemed incapable of actually dealing with the very real pressures we faced when delivering software to non-sprint-friendly customers, timescales, and blockers. So we carried on delivering software with our specs, and some sprinkling of agile terminology. Meetings were called ‘scrums’ now, but otherwise it felt very similar to what went on before.

As a collective fiction it worked, because it kept customers and project managers off our backs while we wrote the software.

Since then I’ve worked in a company that grew to 700 people, and now work in a corporation of 100K+ employees, but the pattern is essentially the same: which incantation of the liturgy will satisfy this congregation before me?

Don’t You Believe?

I’m not going to beat up on any of these paradigms, because what’s the point? If software methodologies didn’t exist we’d have to invent them, because how else would we work together effectively? You need these fictions in order to function at scale. It’s no coincidence that the Agile paradigm has such a quasi-religious hold over a workforce that is immensely fluid and mobile. (If you want to know what I really think about software development methodologies, read this because it lays it out much better than I ever could.)

One of many interesting arguments in Sapiens is that because these collective fictions can’t adequately explain the world, and often conflict with each other, the interesting parts of a culture are those where these tensions are felt. Often, humour derives from these tensions.

‘The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.’ F. Scott Fitzgerald

I don’t know about you, but I often feel this tension when discussion of Agile goes beyond a small team. When I’m told in a motivational poster written by someone I’ve never met and who knows nothing about my job that I should ‘obliterate my blockers’, and those blockers are both external and non-negotiable, what else can I do but laugh at it?

How can you be agile when there are blockers outside your control at every turn? Infrastructure, audit, security, financial planning, financial structures all militate against the ability to quickly deliver meaningful iterations of products. And who is the customer here, anyway? We’re talking about the square of despair:

When I see diagrams like this representing Agile I can only respond with black humour shared with my colleagues, like kids giggling at the back of a church.

When within a smaller and well-functioning functioning team, the totems of Agile often fly out of the window and what you’re left with (when it’s good) is a team that trusts each other, is open about its trials, and has a clear structure (formal or informal) in which agreement and solutions can be found and co-operation is productive. Google recently articulated this (reported briefly here, and more in-depth here).

So Why Not Tell It Like It Is?

You might think the answer is to come up with a new methodology that’s better. It’s not like we haven’t tried:

It’s just not that easy, like the book says:

‘Telling effective stories is not easy. The difficulty lies not in telling the story, but in convincing everyone else to believe it. Much of history revolves around this question: how does one convince millions of people to believe particular stories about gods, or nations, or limited liability companies? Yet when it succeeds, it gives Sapiens immense power, because it enables millions of strangers to cooperate and work towards common goals. Just try to imagine how difficult it would have been to create states, or churches, or legal systems if we could speak only about things that really exist, such as rivers, trees and lions.’

Let’s rephrase that:

‘Coming up with useful software methodologies is not easy. The difficulty lies not in defining them, but in convincing others to follow it. Much of the history of software development revolves around this question: how does one convince engineers to believe particular stories about the effectiveness of requirements gathering, story points, burndown charts or backlog grooming? Yet when adopted, it gives organisations immense power, because it enables distributed teams to cooperate and work towards delivery. Just try to images how difficult it would have been to create Microsoft, Google, or IBM if we could only speak about specific technical challenges.’

Anyway, does the world need more methodologies? It’s not like some very smart people haven’t already thought about this.

Acceptance

So I’m cool with it. Lean, Agile, Waterfall, whatever, the fact is we need some kind of common ideology to co-operate in large numbers. None of them are evil, so it’s not like you’re picking racism over socialism or something. Whichever one you pick is not going to reflect the reality, but if you expect perfection you will be disappointed. And watch yourself for unspoken or unarticulated collective fictions. Your life is full of them. Like that your opinion is important. I can’t resist quoting this passage from Sapiens about our relationship with wheat:

‘The body of Homo sapiens had not evolved for [farming wheat]. It was adapted to climbing apple trees and running after gazelles, not to clearing rocks and carrying water buckets. Human spines, knees, necks and arches paid the price. Studies of ancient skeletons indicate that the transition to agriculture brought about a plethora of ailments, such as slipped discs, arthritis and hernias. Moreover, the new agricultural tasks demanded so much time that people were forced to settle permanently next to their wheat fields. This completely changed their way of life. We did not domesticate wheat. It domesticated us. The word ‘domesticate’ comes from the Latin domus, which means ‘house’. Who’s the one living in a house? Not the wheat. It’s the Sapiens.’

Maybe we’re not here to direct the code, but the code is directing us. Who’s the one compromising reason and logic to grow code? Not the code. It’s the Sapiens.

Currently co-authoring a book on Docker:

0 notes

Text

Diminishing city: hope, despair and Whyalla

This piece is republished with permission from State of Hope, the 55th edition of Griffith Review. Articles are a little longer than most published on The Conversation, presenting an in-depth analysis of the economic, social, environmental and cultural challenges facing South Australia, and the possibilities of renewal and revitalisation.

Exactly 50 years ago, in the spring of 1966, my family left Pennington Migrant Hostel in Adelaide to drive up Highway 1 to Whyalla. Our destination, BHP’s Milpara hostel, was a full day’s journey away in a second-hand faded blue Ford Zephyr.

As recently arrived migrants from Britain, the drive would take us into an utterly unfamiliar landscape: the red-soil and saltbush country of South Australia’s upper Eyre Peninsula.

We were not alone. Whyalla was booming. BHP’s steelworks had opened the year before, the shipyard’s orders book was healthy, while ore from Iron Knob was being shipped from Whyalla in increasing quantities – my father was to work in BHP’s diesel locomotive repair shop.

The Stanleys – like many of Whyalla’s newcomers, working-class Britons (in our case Liverpudlians) – were optimistic about our future in a brand-new Housing Trust semi-detached in a dirt-pavement street on the city’s expanding western fringe: this was the new start in a new, sunny country for which we had left rainy, grey Liverpool.

We were surely not alone. Thousands of other migrants were arriving in the city. In our first year there the Housing Trust constructed over 600 houses. In the decade of the 1960s, Whyalla’s population doubled from 14,000 to 30,000.

BHP helped its employees to build substantial ‘staff’ houses as Whyalla expanded during the war years. These are in Bean Street, named after the compliant SA parliamentary draughtsman who produced the bill that met the needs of ‘The Company’ in developing Whyalla. BHP Archives, Author provided

The newcomers reflected an extraordinary ethnic diversity – booklets promoting the city to migrants spoke of 45 or more ethnic groups living there. The largest groups in the late 1960s came from the British Isles, from elsewhere in Australia and from Europe (mainly Germany, the Netherlands, Yugoslavia, Spain and Poland).

BHP and the City Commission aggressively promoted the city’s advantages. A 1964 BHP promotional booklet extolling its climate, facilities, community amenities and lifestyle (one my family almost certainly read) ended:

This, then, is Whyalla: a place where a young community leads a busy, sunlit life, a city which is growing, always growing.

But the growth of the 1960s stopped in the following decade, when the population had reached around 34,000. In 1978, BHP launched the last of the 64 ships built in Whyalla, bringing to an end the 20-year boom begun with the construction of the steelworks. Between 1977 and 1983, the Housing Trust built only 120 houses. Whyalla began a gradual contraction, one that continues still.

Construction of the blast furnace and associated wharf just before the second world war drew thousands of workers and later their families from the depressed Eyre Peninsula and the Mid North. Author provided

In 1980, sociologist Roy Kriegler published Working for the Company, an analysis of “work and control” informed by his time as a labourer in the shipyard’s final years. He identified what he saw as an intractable dynamic of alienation among those who worked for BHP, a malaise of lack of commitment that infected the city as well as its industrial workplaces.

Kriegler, writing in the wake of the shipyard’s closure, ended his final chapter with a prediction: “Company Town to Ghost Town”. Reports of Whyalla’s demise were premature, but he was not alone in his pessimism.

The first of 64 vessels built at the shipyard before it closed is now the centrepiece of Whyalla Maritime Museum. Wayne Thomas/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

The shipyard’s closure coincided with the growth to maturity of the children of the migrant generation of the 1960s like me. It became usual for young people to leave Whyalla. Among the 75 or so members of my own, very large matriculation class of 1974 many left Whyalla for work or study (as did I). At the 30-year reunion in 2004, no more than two or three still lived in Whyalla.

Many of those remaining found limited opportunities for work and little sense of fulfilment. A survey of drug problems in Whyalla by the Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia in 1985 found “no positive community feeling about Whyalla”, and that “the entire social life of Whyalla revolves around alcohol”.

Not surprisingly, one-quarter of the young people interviewed said they drank “because there is nothing better to do in Whyalla”.

Living through times of hope and despair

I came to know several of Whyalla’s incarnations. I had grown up there in the boom years, had worked at the steelworks in vacations, and while driving taxis became closely acquainted with Whyalla’s pub and clubs. I also wrote a Litt.B. thesis about the town’s voluntary war effort during the second world war, which the council published.

Through that research I gained an understanding of both the earlier wartime boom and of the insular little community it had disrupted. And because I continued to visit the city, over the ensuing 40 years I saw it diminish.

The shipyard’s closure hit Whyalla hard, but it went down fighting. Community workshops cast about for ideas to generate a sustainable economy. Ideas to diversify the city’s economy included rabbit farming, a ferry (or even a bridge!) across Spencer Gulf and exploiting the ever-elusive tourist dollar. None came to much.

Looking up Patterson Street, the main street of ‘old’ Whyalla, to the second world war defence emplacements, one of the city’s many features that the council attempted to turn into tourist attractions. Peter Stanley, Author provided

From the 1980s, Whyalla became better known for providing a home for welfare recipients than for producing ships and steel – its Housing Trust stock allegedly enabled beneficiaries in Adelaide to be offered accommodation if they were willing to move to Whyalla.

With the arrival of Indo-Chinese, South American and East African refugees in successive decades, Whyalla maintained its ethnic diversity. This included a small community of Indigenous people, some Barngala, the region’s original inhabitants.

Looking back over the century since BHP renamed the little ore-shipping port of Hummock Hill Whyalla in 1914, we can identify cycles of hope and despair against the larger rhythm of expansion and then contraction.

For at least 50 years Whyalla has seen optimism and idealism but also, if not despair, then its close neighbours, alienation and apathy. The city has seen repeated contests between hope and pessimism. Both seem to be embedded in the city’s culture, in its people’s repeated responses to the challenges of their situation.

Postwar boom upset the old stability

Whyalla had been a tiny company town until the late 1930s. It was simply an ore jetty and a railway workshop, loading iron ore from Iron Knob, 50 kilometres away in the Middleback Ranges.

In its first incarnation as a small ore-shipping port, Whyalla had been remarkably stable. The 1934 federal electoral roll, for example, listed some 800 voters, but the surnames of five families accounted for a tenth of residents. Whyalla seemed free of the sectarianism endemic to Australia 80 years ago – the town’s Catholic and Anglican ministers played in the town’s orchestra.

Premier Thomas Playford opens the Morgan-Whyalla pipeline in 1944, ending years of water shortages and enabling residents to plant gardens to make the town more pleasant. As the Murray River’s salinity rose, the water quality declined, becoming virtually undrinkable. SA Water/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

In the late 1930s, the Playford state government persuaded (and subsidised) BHP to build a blast furnace, and a shipyard followed in 1940.

The town’s expansion upset the old stability. During the second world war the town grew from fewer than a thousand inhabitants to nearly 7,000, most drawn from the economically depressed Eyre Peninsula and Mid North.

The war years brought hardship – many families attracted to the town by war work lived in tents and shacks in what was called “Siberia” – but also a sense of hope after years of worldwide, national and local economic depression. People built their own houses, bought them under the company’s scheme or sought Housing Trust homes – small, but well-built and secure after the rural poverty many had known.

These Housing Trust homes in Goodman Street were built to house the many people who migrated to Whyalla to work in the shipyard and the blast furnace in the early 1940s. Residents’ groups agitated to have the streets sealed, the cost of which was a factor in BHP accepting calls for elected local government in 1945. BHP Archives, Author provided

Houses in the same area of Whyalla South 60 years later show how Murray water helped ‘green’ the city. What will happen as the wartime housing stock ages is a pressing question. Peter Stanley, Author provided

But the war also saw tensions between old residents and new. Established residents dominated the town’s social organisations, especially its voluntary war effort. Newcomers were, however, active in pressing for civic improvements and for improved working conditions in the company’s shipyard and blast furnace.

Under the leadership of trade unions and groups such as the Housewives’ Association, newcomers pressed for price controls, new schools, bread and postal deliveries, telephone and bus services, cheaper water and better housing. They expressed a powerful idealism characteristic of a generation that fought and worked for a better world.

While established residents accepted the company’s paternalism, newcomers (almost all from rural South Australia) pressed for representative local government. BHP, reluctant to pay for the larger, more expensive town services but equally loath to relinquish control, engineered a compromise in the form of a town commission.

The commission, established by the state government in 1944, comprised three representatives each of company and residents, chaired by an independent commissioner, Charles Ryan (who held the position from 1945 to 1970).

BHP was ‘not very pleased with the results’ of the first town commission election – it later sacked an employee, Eric Stead, who had been elected as a residents’ representative. Trove/National Library of Australia

The commission reflected idealism, pragmatism and paternalism. The elections for the first town commission in 1945 revealed the extent to which many of Whyalla’s newcomers yearned for a better society. The three ratepayers’ representatives included Eric Stead, a member of the Communist Party and an embodiment of the “progressive” movements in the town.

“Naturally, we are not very pleased with the results,” the company’s director in Whyalla reported to head office in Melbourne.

Stead’s election reflected, of course, the Communist Party’s popularity generally at the end of the war. But it also disclosed the deep yearning for a better life among a generation traumatised by economic depression and war; Whyalla’s new houses and company-subsidised services could provide that life.

Many of those attracted in wartime moved on after 1945, but those who stayed formed an enlarged “old Whyalla” – notably loyal to the paternalist BHP (naturally, known to residents simply as “the company”). That stability was disrupted once more from the late 1950s. Again supported by a state government (still Playford’s), BHP built a steelworks at Whyalla. This created the boom that brought the Stanleys and tens of thousands of other newcomers to the city.

A city of contradictions

Whyalla’s sense of itself as a community – as distinct from the dismal catalogue of deprivation on a range of socio-economic indicators – has never been clearer than in the Australian Frontier report of 1973, at the height of the second boom.

Produced by a Melbourne social research consultant in response to a request by the new Whyalla City Council (which supplanted the commission in 1970), the report investigated the “Factors Influencing the Stability of Whyalla”. It drew on a “Community Self Survey” co-ordinated by a Congregational Church social worker, Don Sarre, notable because it reflected the views of residents rather than planners.