#I was anxious about folks interpreting this in bad faith

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

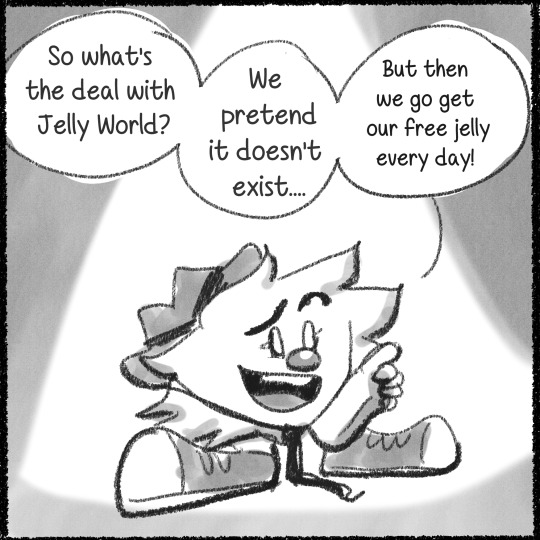

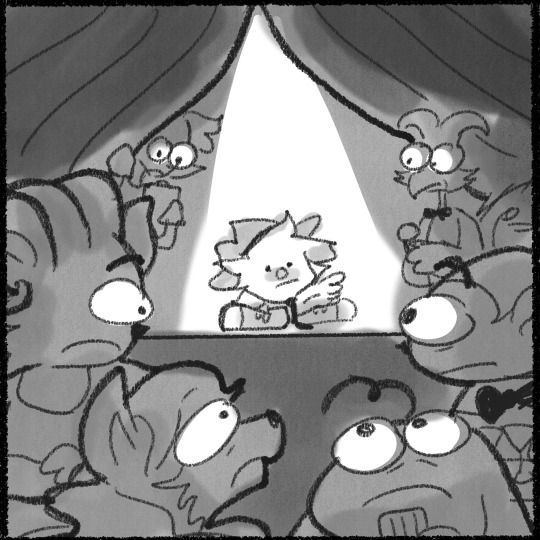

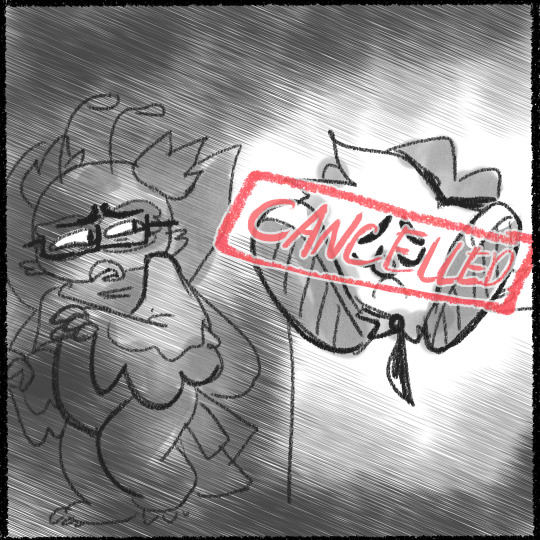

Okay so this comic came about because while looking up what fashion options existed on the site, I came across this 'cancelled' stamp. Apparently it's a reference to an April Fool's gag the site does, but I got it because nothing is funnier to me then my sweet looking JubJub having this stamped on top of her:

When sharing this discovery with others online, a question that kept popping up was 'man what did she do to get cancelled', and so this comic explaining how she could possibly get cancelled in the world of Neopets came about. After all, there's no such thing as Jelly World....

#Neopets#comic#comics#I was anxious about folks interpreting this in bad faith#but so far it seems that people have understood the intended tone and have found it enjoyable#so I'm deeply thankful for that#also for those who don't get the Jellyworld Stuff: it's a world that exists but the entire site pretends it doesn't#It's a inside joke for the site and one that has been upheld all this time....I love it#You can't make references to it in the Neopian Times unless you go 'this doesn't exist and it's ridiculous'#Or if the person shown as saying 'Jelly World exists' is treated as saying something ridiculous and no one believes them

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Defense of Fat Thor

I not only enjoyed Thor’s portrayal in Endgame, but found it to be a productive and well-developed(/acted, DAMN, Chris Hemsworth) characterization that has been steadily building up across each consecutive movie. Caveat: I do not fault anyone for being skeptical that the directors, etc. had it in them, considering the clunky nature of some of their previous creations, to say nothing of some of their interviews, etc. I am also not 100% surprised to see people maligning Fat Thor, and/or saying they don’t understand his trajectory and/or that they felt some of the humor at his expense took away from the legitimacy of having a fat, depressed, anxious character able to accomplish the same feats as when he had more physical prowess, etc. I disagree with this as well, in part because Fat Thor feels very personal to me, though not exclusively, and at the very least would like to propose a reading of many of the scenes in Endgame that offers a considerably more well-intentioned and good faith portrayal of Thor, with my own caveat that at least the anti-Ragnarok people using Fat Thor to further their agenda that Thor’s characterization sucks because Chris Hemsworth and Taika Waititi spent each day on set shaking Tom Hiddleston down for his lunch money and laughing at their own fart jokes are still wrong, which balances out everything else, because balance is still important, even if Thanos’ fuckboy interpretation of it is ridiculous. Anywho, apologies in advance for how messy this ends up being, I feel like my thoughts are very roundabout right now, but getting it out of my system will really help.

Thor has been ~emotionally fat~ for a while now, folks. As far back as Thor (2011), we see him disassociating, aka spending at least a few moments staring off into space in the midst of dealing with sudden upheaval, often because his angry outbursts have failed to be satisfying or get him what he wants/needs. One of the things that made me so excited to see a physical fallout to this in the MCU is that it actually ties into a bunch of other canons, too, including a recent spell in the comics leading up to the War of the Realms, wherein Odin sort of admits to his own role in breaking Thor, as far back as being “too drunk” to be there for his birth, as well as his being dubbed the God of Thunder because baby Thor used to wail whenever there was a storm, and Odin used to make fun of him for it because you don’t get a #4 Best All-Father coffee cup from your kids for nothing. @thishereanakinguy and I are even reworking parts of our Thorki paper for publication to put forth even more evidence that the pressure on Thor to be the Golden Child was too much, and that he’s been unraveling for a long time.

Again, none of these reactions to turmoil are new for Thor, though it’s fascinating that the conversation between Frigga and Thor in Endgame is largely focused on her assuring her son that it’s okay for him to fail, and/or for him to delegate tasks (there’s a recent comic that’s gone viral where Mister Rogers visits with Thor, and it has a similar bent), or realize that he has to shift his perspective on Who He Is. In part, it’s lowkey hilarious that Frigga, aka “send Loki some soup and some library books he’ll enjoy after our big fight because I still love that little asshole, never mind that he’ll probably receive them after she has been killed omfg,” is so blatantly ignoring Odin’s decrees to basically withhold basic affection from their children so that they’ll toughen up on their own, because fuck that noise. At the same time, Frigga imparts words that Thor (and Loki) should have heard and taken to heart a long time ago, and it’s painful to realize that Thor has felt as though he hasn’t been allowed to express his feelings, but so God damned great that that’s what Frigga hones in on. Notably, Thor isn’t trying to botch his trip to 2013 Asgard, either; he has a panic attack when he and Rocket arrive, and Frigga sneaks up on him because Frigga knows her babies no matter how much they are made of pizza or in Loki’s case magical artifacts. (Sarah read something saying that in households where the Golden Child and Black Sheep co-exist, statistically it’s common for the Golden Child to turn to alcohol and food, whereas the Black Sheep is more likely to turn to drugs/more illicit substances wherein they opt not to feel their feelings as much, and I was really floored by that because that really fits a couple of different scenarios that I’m familiar with for one reason or another.)

SO ANYWAY, we see Thor disassociating in previous movies. In TDW, even Odin comments on Thor’s confused heart, which Thor assures him has nothing to do with Jane Foster, even though it would be very easy for him to pretend he’s not actively thinking about Loki a thousand times a day and spending so much time stalking Heimdall and the broken Bifrost remnants that dude is like holy fuck please talk to your kid or I am going to commit treason again so hard. Thor reaches out to Odin for guidance/arguably comfort once Frigga dies, and his inability to provide either sends Thor immediately to Loki, who at the very least can help him properly realize the revenge he seeks, while also saving Jane. In Ragnarok, we get that great moment where Loki is talking directly to Thor, and Thor simply stares straight ahead; Loki doesn’t seem all that surprised by it either - he and Thor have different triggers and whatnot, but he knows the emo fuck who ends up at his cell in a fucking black poncho and handcuffs isn’t a new creation by any means, and he is into it fwiw. Even stuff like Korg admitting at the end of Ragnarok he carried around Miek’s presumably dead body because he felt so bad that he was dead warrants a little nod of understanding from Thor. Likewise, we see Thor stress-eating a bowl of bread at the beginning of Endgame, before the focus on his weight became a thing. Thor doesn’t run outside to see Tony Stark come home; whenever possible, he’s barely there, even before his five-year hiatus.

The use of well-placed humor in a three-hour sob fest does not seem all that weird to me. Shakespeare does it in all of his tragedies; and to continue this egregious metaphor, a lot of his comedies contain tragic bits, aka loss of family identity, which is arguably something that underpins how good Ragnarok is, as well. Being able to laugh at stuff has always been very important for me personally, though I realize it’s not for everyone. Still, I think there’s an additional caveat with Endgame regarding who the ‘fat jokes’ are coming from, aka arguably all of the Avengers have their own significant traumas to work through even before The Snap, and are also just trying to survive, even if they seem to fare physically better than Thor at this particular point in time. So Tony Stark calls him “Lebowski”; but as soon as the musical cues and Hemsworth’s amazing acting switches over into Thor being triggered by thoughts of all that he’s lost only minutes later, we see Tony, who canonically has major issues with being touched, putting his hand on Thor’s shoulder and allowing himself to be grabbed and held because he knows that is what Thor needs from him. Bruce, too, has to set a boundary for his own personal safety about being grabbed, but still gives in to Thor’s need for physical touch. One of the tragic touchstones of Ragnarok is that Thor doesn’t touch Loki once, even though in the first two Thor films and Avengers 1, he is constantly pawing at him. Thor wants to make a point in Ragnarok that he has decided he must let Loki go if that’s what Loki truly wants, and so he withholds his own instinct for physical contact - which Loki gives back to him, however briefly, in Infinity War by knocking Thor out of the way of Thanos and the Tesseract, to say nothing of how all Thor can do when he arrives at Loki’s corpse is to mewl and cling and bury his head and wait for everything to explode, himself included.

In any case, the other 'fat jokes’ come from Rocket, well established as being caustic in the face of personal tragedy, and having been put in the position even back in Infinity War of sort of making sure Thor keeps going, and Rhodey, who is probably just trying to deal with all these new people hanging around, and the fact that all of the structure in his life pretty much has been upended in a really short amount of time. Regarding Frigga’s “eat a salad” remark, as his mom, she seems to understand how much his physicality comes into play for him, and how devastating it is for him to see how others react to him seeming both physically and emotionally diminished. This is why it’s so powerful for him to still be 'worthy’ of Mjolnir, I think, and why that moment book-ended Frigga’s admonishment. Likewise, we don’t get a suspiciously fast glow-up wherein Thor’s all muscley again. He has to hold his own against Thanos in his current form, and he fucking does. Sometimes, life happens, and you have to respond to it as you are because you don’t have the time or energy to get everything in order first, and so you do the best you can. IMO, Thor did a pretty fucking good job.

I also find it completely understandable that Thor went off with the Guardians at the end of the film. (P.S.: Peter Quill is still absolutely intimidated by Fat Thor.) For one thing, I don’t think he’s going to stop trying to find a way to bring Loki back, regardless of what Clint said about the Soul Stone’s magic not being able to be reversed. For another, Valkyrie deserves her own glow-up into becoming Queen of New Asgard, as much as Sam deserves to be the new Cap. I’m of the mindset that Steve likely wouldn’t have gone back in time to be with Peggy if Tony had lived, and that doing so was him honoring Tony’s legacy by taking the advice that he gives several times in the film to go and live life while you have it. Likewise, as sad as it is for Tony to have died, I’m not sure he would have been able to rest, post-Thanos. You also can’t tell me for a second he hasn’t left all sorts of little messages and trinkets and whatnot around for his loved ones to find, cough AI Tony in Peter’s next suit or something cough.

Overall, I thought Endgame was a good send-off. It was well-acted, well-scripted, beautifully scored (Thor’s Pink Panther-esque theme when he’s trying to explain the Aether is amazeballs, as well as the theme that plays when everybody gets to the battlefield), and really just surprisingly, suspiciously good. I am glad that if we have to see this leg of the MCU end that it did so in such a way as to leave character arcs open to further interpretation, and I’m legitimately excited for a lot of them. While I don’t think everybody is required to be fake-positive all of the time, I do think that in fandom spaces, if one’s sole focus is how disappointing something is all the time, it’s not a productive or soul-enhancing use of one’s energy, and it makes me sad to see it. Nuance is important; the MCU has more of it than it’s given credit for having, and I hope more people realize that as it continues into Phase 4, or at the very least, that they find something they enjoy and keep coming along for the ride.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Destiel Season 13: A catalog of Supernatural episodes

A catalog of each episode in Supernatural that features scenes related to Destiel. This includes scenes between Dean and Castiel, scenes with other characters that address their relationship with each other, and scenes that allude to Dean’s bisexuality.

Season 13 Summary Analysis

Dean is destroyed by Castiel’s death at the hands of Lucifer, and he is hard on Jack at first because he believes Jack is partially to blame. Dean has lost hope and given up on life, and not even Sam is able to snap him out of it. When Cas returns, Dean’s attitude takes a 180 degree shift, and he becomes softer with Jack after learning that he’s the one who brought Cas back. Dean, Cas, and Sam become highly protective co-parents to Jack. Dean and Cas establish a much more domestic relationship and are better than ever at communicating and apologizing to each other.

My interpretation: Dean has trouble adjusting to life without Cas, and he takes it out on Jack because he feels like Jack is the reason Cas pulled away from him in Season 12. When The Empty tries to intimidate Cas into going back to sleep, Cas fights back because he knows that Dean and Sam need him. He is no longer paralyzed by his past mistakes because Dean showed him unconditional love in Season 12. When Cas returns, Dean and Cas are ready to accept their true feelings and commit to each other for real—they have each finally worked past their periods of self-loathing and are ready to accept each other’s affection. Although we never see Dean and Cas explicitly state that they are in a romantic relationship, they repeatedly exhibit loving behavior toward one another and allude to time they have spent together off screen. Dean and Cas are both significantly happier, and even Sam is glad that they’ve finally set aside their self-hatred and baggage to finally be together.

13.01 Lost and Found

Dean cannot bring himself to say out loud that Cas is dead: “Let’s see, Crowley’s dead, Kelly’s dead, Cas is... Mom’s gone, and apparently, the Devil’s kid hit puberty in 30 seconds flat. Oh, and almost killed us.”

Dean prays to God to bring Cas back and punches a wooden sign out of frustration: “Okay, Chuck, or God or whatever, I... I need your help. See, you left us. You LEFT us. You went off, you said the Earth would be fine because it had me and it had Sam, but it’s NOT, and WE’RE not. We’ve lost everything, and now you’re gonna bring him back, k? You’re gonna bring back Cas, you’re gonna bring back Mom, you’re gonna bring ‘em all back. All of them. Even Crowley. ‘Cause after everything that you’ve done, you OWE us, you son of a bitch. So you get your ass down here, and you make this right, right here, and right now!”

Dean can barely look at Castiel’s dead body. He struggles with his emotions while wrapping Cas up with care and preparing the funeral pyre.

13.03 Patience

Dean explains that he associates Jack with the loss of Cas and can’t let it go: “I can hardly look at the kid. ‘Cause when I do, all I see is everybody we’ve lost.” “Mom chose to take that shot at Lucifer. That is not on Jack.” “And what about Cas?” “What ABOUT Cas?” “He manipulated him. He made him promises. Said ‘Paradise on Earth,’ and Cas bought it. And you know what that got him? It got him dead! Now, you might be able to forget about that, but I can’t!

13.04 The Big Empty

When Cas tries to convince The Empty to send him back to Earth, The Empty intimidates him with his fears and failings: “Sam and Dean need me.” “Oh, save it. I have tiptoed through all your little tulips. Your memories, your little feelings, yes. I know what you hate. I know who you love, what you fear. There is nothing for you back there, no.”

Dean admits to Sam that he’s broken: “I need you to keep the faith for both of us. ‘Cause right now I... Right now, I don’t believe in a damn thing.”

13.05 Advanced Thanatology

Sam makes an effort to be extra nice to Dean to try to help him get through his rough patch: “I’m fine.” “No, you’re not, Dean. You said you don’t believe in anything, and that’s not true, that’s not you. You DO believe in things. You believe in people. That’s who you are, that’s what you do. I know you’re in a dark place, and I just wanna help.” “Okay. Look, I’ve been down this road before, and I fought my way back. I will fight my way back again.” “How?” “Same way I always do—bullets, bacon, and booze. A lotta booze.”

Death (aka Billie) recognizes that Dean has lost his zeal for life: “You have changed, and you tell people it’s not a big deal. You tell people you’ll work through it, but you know you won’t, you can’t, and that scares the hell outta you. Or am I wrong?” “What do you want me to say? Doesn’t matter. I don’t matter.” “Don’t you?” “I couldn’t save Mom. I could save Cas. I can’t even save a scared little kid. Sam keeps tryin’ to fix it, but I just keep draggin’ him down. So I’m not gonna beg, okay? If it’s my time, it’s my time.” “You really believe that. You wanna die.”

Dean admits to Sam that he is not okay: “You know, my whole life, I always believed that what we do was important. No matter the cost, no matter who we lost, whether it was Dad, or Bobby, or... And I would take the hit, but I kept on fighting because I believed that we were makin’ the world a better place. And now Mom, and Cas, and I don’t know... I don’t know.” “So now you don’t believe anymore.” “I just need a win. I just need a damn win.”

As Dean learns that Cas is alive, the song “Never Too Late” by Steppenwolf plays, and the camera cuts between Cas and Dean (not Sam): “Your eyes are moist, you scream and shout, as though you were a man possessed. From deep inside comes rushing forth all the anguish you suppressed. Upon your wall hangs your degree, your parents craved so much for you. And though you’re trained to make your mark, you still don’t quite know what to do. It’s never too late to start all over again. To love the people you caused the pain, and help them learn your name. ... You say you've only got one life to live, and when you're dead you're gone. Your family comes to your grave, and with tears in their eyes, they tell you you did something wrong. ‘You left us alone!’ Tell me who's to say after all is done and you're finally gone, you won't be back again. You can find a way to change today, you don't have to wait 'til then. It's never too late to start all over again.”

13.06 Tombstone

Dean gives Cas a big hug when he sees him: “Welcome home, pal.” “How long was I gone?” “Too damn long.”

Dean, who was borderline suicidal in the previous episode, does a complete 180 mood shift and gets excited to go on a hunt in Dodge City: “Alright, well, two salty hunters, one half-angel kid, and dude who just came back from the dead, again. Team Free Will 2.0. Here we go!”

When the gang enters the Wild Bill Suite, Dean nerds out about the historical figures hanging on the walls, and Cas is knowingly resigned to it: “He really likes cowboys.” “Yes. Yes, he does.”

Sam recognizes how happy Dean is: “You’re in a good mood, huh?” “Yeah, and?” “Nothin’. I just, uh... you’ve been havin’ a rough go, so it’s good to see you smile.” “Well, I said I needed a big win. We got Cas back. That’s a pretty damn big win.” “Yeah, fair enough.”

When Jack goes to wake up Dean, Cas tries to stop him, knowing how badly Dean will react to being woken up. Cas later comments on Dean’s sleeping habits: “I told you. He’s an angry sleeper. Like a bear.”

When Cas gets up to leave, Dean lifts his finger and points at his coffee. Cas understands the gesture to mean he should wait until Dean has finished his coffee and sits back down.

Cas reluctantly goes along with Dean’s insistence that he should act like a cowboy, and they reference a movie night that they’ve had at some point in the past: “Alright, listen, these Dodge City cops aren’t likely to trust big city folks, so we’re gonna have to blend.” “Which is why you’re making me wear this absurd hat.” “It’s not that bad. Well, actually, yeah, it kinda is. Hang on. [Dean removes the band from Castiel’s cowboy hat.] Alright, that’s better.” “Is it?” “Yeah. Look, just act like you’re from Tombstone, k?” “The city?” “The movie! With Kurt Russel? I made you watch it.” “Yeah, yeah. Yeah. The one with the guns and tuberculosis. ‘I’m your Huckleberry.’” “Yeah, exactly. It’s good to have you back, Cas. Alright, follow my lead. We’ll fit right in.”

When Jack shows remorse for accidentally killing someone, Dean tries to make him feel better, demonstrating that his view of Jack has shifted: “Maybe you’re right. Maybe I’m just another monster.” “No, you’re not. I thought you were. I did, but, like Sam said, we’ve all done bad. We all have blood on our hands. So if you’re a monster, we’re all monsters.”

13.07 War of the Worlds

Cas says he’s going to ask the angels for help finding Jack, and Dean insists on going with him. Dean reluctantly agrees to let Cas go alone and tells him not to get in into any trouble: “Dean, you can’t accompany me. My contact is already anxious about meeting and won’t speak in the presence of a stranger.” “So introduce me. Then I’m not a stranger. I’ll bring a six pack.” “Dean, I swore I would protect this boy. Let me do this.” “Don’t do anything stupid.”

When Lucifer catches Cas talking to Dean on the phone, Cas tries to play off the conversation as casual by speaking lovingly toward Dean: “Yes, I would like to see you, too. The sooner, the better.”

Sam recognizes that Dean is worried about Cas: “Don’t worry. You did tell him not to do anything stupid.” “Right. When’s the last time that’s worked?”

13.08 The Scorpion and the Frog

Sam recognizes that Dean believes in himself and his purpose again: “We’ll figure somethin’ else out. And if that doesn’t work, then we’ll move on to the next, and then whatever’s after that. We just keep working, ‘cause that’s what we do.” “It feels really good to hear you talk like that again.” “I’ll drink to that.”

13.11 Various & Sundry Villains

When Dean shows up saying he’s in love and “full on twitter-pated”, Sam is amused and surprised that Dean would express emotion like that so openly, until he realizes Dean is under a spell.

13.13 Devil’s Bargain

When Dean scolds Cas for talking with Lucifer, Cas defends himself: “Cas, I specifically told you not to do anything stupid.” “Well, he was weak, and given the context of our imminent annihilation, it didn’t seem stupid.“

Dean apologizes to Cas for not realizing that Asmodeus was posing as him while he was captured, and Cas forgives him immediately: “Cas, I’m sorry. All that time you were with Asmodeus, I... We should’ve known it wasn’t you.” “Well he’s a shape-shifter. Besides, I was the one who got myself captured.” “Yeah, but if Sam and I knew, you know, we would’ve...” “Yeah, I know, I know. You would’ve tried another long shot. I’m fine, Dean.”

Dean expresses concern for Castiel’s well-being, and Cas expresses concern for the safety of their shared family: “I’m fine, Dean.” “You sure about that?” “Right now, all that matters is getting Jack and your mother out of that place, okay? Look, I promised Kelly that I would protect her son. I intend to keep that promise.”

Cas understands Dean’s colloquialism: “We’re boned.” “Epically.”

When the boys encounter Ketch, Cas looks over at Dean and instinctively knows that Dean wants him to put Ketch to sleep.

Cas loathes Ketch on Dean’s behalf, agreeing with Dean’s plan to kill him: “I say we take dick bag here back to the bunker, find out what he knows and put a bullet in him, burn his bones, and flush the ashes.” “I like that plan.”

While the boys are talking about whether they can trust Ketch, Cas rolls his eyes at Dean’s predictable penchant for violence.

13.14 Good Intentions

Dean volunteers to accompany Cas to go fight Gog and Magog.

Dean shows concern for Castiel’s emotional well-being and considers his wants and needs. Cas is open about his worries for the future, and Dean shows him support: “How’re you holdin’ up, Cas?” “I’m fine.” “No, I just mean with, you know, everything you’ve been through, and I know you really wanna find Lucifer.” “No, it’s not that. It’s about... Well, it is that, but it’s also, I... Dean, I was dead.” “Temporarily.” “And I have to believe that I was brought back for a reason.” “You were, k? Jack brought you back because we needed you back.” “Right. And how have I repaid him? I promised his mother that I would protect him, but now he’s trapped in that place while Lucifer is here, who’s... he’s getting stronger and more powerful by the day. And if Michael really is coming, maybe I was brought back to help prepare.” “Prepare for what?” “War. War, is what Michael does.” “Well, then we do what we do, whatever it takes.”

Dean rolls his eyes at Castiel’s predictable seriousness: “Well, Enochian’s kinda tough. Maybe you got a word wrong.” “I don’t get words wrong.” *eyeroll*

After Donatello tries to hurt Dean by casting a spell on him, Cas gets angry and disregards Donatello’s safety, forcefully extracting the information they need from his mind: “I’m sorry, but I’m not going to let you or anyone hurt the people I love, not again.”

Dean is angry at Cas for making Donatello braindead, but Cas convinces him it was necessary due to their dire circumstances.

13.16 ScoobyNatural

Dean is antagonistic toward Fred for most of the episode, but it seems to be based in jealously, and perhaps a certain level of attraction: “Hey, why do you hate Fred so much?” “He thinks he’s so cool, with his perfect hair, his can-do attitude, that stupid ascot.”

Dean starts out pursuing Daphne, but her disinterest toward him and commitment to Fred help Dean see Fred’s value. Dean develops more respect for Fred as the episode progresses, and he even seems to develop a particular fondness for Fred himself, emulating his style by wearing an ascot.

When Cas asks Dean what happened with the Cartwright twins, he evades the question.

13.18 Bring ‘Em Back Alive

Cas is upset that Sam let Dean go to Apocalypse World on his own: “Dean is in Apocalypse World alone?” “No, he’s with Ketch, so he’s not alone.” “Because that makes it so much better.” “Cas, he wanted to go solo.” “And you let him?” “I... He didn’t give me much of a choice. Anyways, Dean’s right. As long as he’s over there and we’re here, we need to be taking care of Gabriel, getting him right again.”

Dean makes a joke to Ketch about his own sexuality: “You don’t look good.” “Yeah, well, you’re not my type, either.”

When Dean gets upset about losing Gabriel, Cas tries to calm him down and make him feel better: “Dean, we will find Gabriel. We will.” “We better.”

13.19 Funeralla

When Rowena flirts with Cas, Dean is visibly annoyed and Cas is awkward about it.

Dean asks Cas if he wants a beer. Cas says no, but Dean gets one for him anyway.

Cas makes a sports reference and Dean is impressed. Then Cas makes it awkward and Dean resists the urge to tell a dirty joke: “This would be something of a Hail Mary.” “Hmm!” “It’s a sports term, like slam dunk or, uh... ball handler.” “That’s uh... mnh-mnh.”

Dean and Cas talk through a disagreement without being accusatory or disrespectful: “I don’t think that’s a good idea.” “Well, Dean, we don’t have any good ideas.” “Okay, let’s just not barrel through with that like, uh, you know, like the Donatello thing.” “We had our disagreement, but we got results.” “That didn’t make it okay.” “I hear your concerns. And yes, the angels, they loathe me, and there’s going to be dangers, but heaven doesn’t want the world to end any more than we do. This is something that I have to try.”

Dean reluctantly supports Castiel’s idea after realizing how important it is to him: “Cas, you wanna try this angel thing, then go for it. Just don’t get dead again.”

13.21 Beat the Devil

When the gang goes through the portal, Gabriel stumbles and ends up with his face in Castiel’s crotch, which makes Dean visibly uncomfortable.

When Sam is mortally wounded and taken by vampires, Cas protectively stops Dean from going after him.

13.23 Let the Good Times Roll

Cas tries to stop Dean from letting Michael possess him: “Dean, you can’t.” “Lucifer has Sam. He has Jack. Cas, I don’t have a choice!”

Cas is visibly grief-stricken at losing Dean to Michael.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've been doing a lot of growing in my christianity lately, and I have found this blog soooooo helpful, especially as bi christian going to a conservative christian high school. In my school they talk a lot about original sin as a result of The Fall, and that concept seems wrong to me, but I can't really intelligently describe why. Do you have any resources or links that deal with the issue of original sin and could help me understand why some Christians reject the concept?

Hey there!

For anyone reading this who isn’t sure what Original Sin is, it’s the belief held by many Christian traditions that after Adam and Eve ate the fruit of knowledge of good and evil, all humans after them have been corrupted with sin – you might think of it as sinfulness being passed down in our DNA, so that even newborns are tainted by sin.

This concept was first proposed by Saint Augustine, who developed it from Paul’s statement that “Therefore just as through one man sin entered into the world, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men, because all sinned…” (Romans 5:12).

I’m with you on pondering whether the traditional concept of original sin is quite right – I still have not discerned for sure what I think on the subject, but I can say that the concept of Original Blessing strikes a much richer chord in my spirit.

“Original blessing reminds us that we are in a relationship with God, and God started it, and God is sticking with it.” The above article is sort of long, so see this post for my favorite quotes from it if you don’t have time for the whole thing.

I am torn when it comes to this idea of original sin because on the one hand, it is true that all human beings do some or many bad things in their lives – no one but Jesus (and if you believe as I and Catholics do, Mary) has ever lived a sinless life, perfectly in line with God’s will.But on the other hand, do our sins mean we are evil at the core? or are we good at the heart of ourselves, underneath whatever sins we’ve committed (or, says original sin, we are born with)?

Original sin implies that humans are bad at their core (look up the concept of “total depravity” or “inherent evil”) – but one of God’s first descriptions of human beings was to call us (and all Creation) “very good” (Genesis 1:31). It is as the above article on original blessing says – how can we dare to consider that any human action, such as Adam and Eve eating the fruit, could “undo what God has ordained”?

Rabbi Avner Zarmi agrees (as Judaism rejects the concept of original sin): “At every stage of the world’s creation, G-d pronounced it tov [good] before proceeding to the next stage. On the creation of mankind, He pronounced it tov me’od (‘very good’), and there is no indication thereafter that He changed his mind.”

Moreover, Genesis does not have any point where it explicitly states that Adam and Eve brought sin into the world with their actions (it does not even say that before “the Fall” they were incapable of sinning, though I do think “then their eyes were opened” in 3:7 can be interpreted as implying that).

In the end, whether or not original sin is a real thing does not change what God has called us to do: to love God and neighbor, to act with justice and love mercy, to glorify God with our lives. So I think it’s okay to be unsure on the matter – to keep pondering it but not to become too anxious about the answer. We can have faith that whether or not original sin is real, God is with us, God calls us good, God liberates us from sin.

I also have found for myself that it is better to think of human beings as capable of good, rather than to think of them as inherently evil. When I focus on the former, I am inspired to do good, and I am able to see the good others have done; when I focus on the latter, I tend to become cynical and bitter towards myself and my fellow human beings.

I do believe that all goodness comes from God and so we rely on God for any goodness we can do; but as we are in God’s image, and as God has declared us good, that goodness is inside us, at the heart of us – not evil.

Do other folks have good resources describing original sin, whether they support or reject the concept?

#original sin#original blessing#sin#mostlyvoid stars#queerly christian asks#i've worded everything so poorly here lmao#this is one of those posts where i'll look at it again in a year and be like why. why did i write that

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Artist: Conor Oberst Author: Conor Oberst Album: Ruminations Year: 2016 Genre: alternative/folk/anti-folk

TITLE

A “next of kin” (NOK) is a person’s closest living blood relative or relatives. It is a legal definition in the United States (where Conor lives). According to legal systems, in cases of medical emergency, the next of kin may participate in medical decisions when their relative is incapable of such. This term is not used anywhere in the song itself, except for the title. Its nature, related to legal issues (jargon), may indicate that the author wants to separate himself from the issues presented in the song (death, loss, hopelessness) by using a term which doesn’t necessarily have any emotional connotations in order not to feel sadness himself. He may also use it ironically to point out that people, when in difficult, life-challenging situations (such as death of a beloved person), are limited to the system and its bureaucratic procedures, having no room left for sentiment, nostalgia and pain.

VERSE 1

The speaker admits to seeing a (supposedly) car crash on the interstate highway which moved him deeply to the point he couldn’t get rid of the feeling. The crash must’ve been fatal, with certain person(s) dead as a result, since he ironically points out that the dead person’s relative (next of kin?) must be notified, as restricted in a database. The speaker now reveals that he is, in fact, to notify the relative. He again admits that he feels uneasy as he doesn’t want to call that person nor inform them. Did he know the deceased? Does he know the relative? Or is he just as empathetic? He tells the relative that he has bad news and asks them to sit down to not fall unconscious (possibly). It’s worth to notice that the mentioned “interstate” sounds similar when pronounced to “intestate” which refers to the condition of the estate of a person who dies without having made a will or other declaration.

VERSE 2

We now switch to a different scenery. We’re presented with an image of a bathrobe hanging on somebody’s bedroom door. It belonged to a woman who’s clearly a year gone by the time. Her closest one, possibly a relative, a man (a husband? partner? father? brother? A partner more than anyone else, given the image of a shared bedroom) buried her body by a sycamore, a tree which in Catholicism symbolizes clarity (Zacchaeus climbing it to see Jesus clearly among a crowd of people). The tree is a symbol of place in the lives of Catholics where they’re able to have a clear vision of Jesus, their savior. In Egyptian Texts, two sycamore trees stood at the eastern gate of Heaven. Between the trees the Sun God, Ra, showed himself each morning. It is believed that a sycamore tree and its valuable wood (often used to carve sarcophagi, or coffins) was a symbol of protection for the Egyptians during the journey from life to death. I think it’s safe to say that the author could’ve had both symbolic connotations in mind. He tells us that the man, grieving his wife’s death, buried her under the sycamore. By “the” & the following line we know it’s not a random one, but possibly a tree growing in their garden or somewhere near home, since the man wants to “keep his wife/partner close”, aka wants to have “the best view” to visit her grave often and to have it protected, near. We’re later told that “it”, the man’s partner’s death was devastating to him both emotionally and physically. It “made him old” which may refer to him changing physically (people’s hair, for example, can turn gray within seconds of a traumatic experience) or/and mentally (loss of a loved one is a life-changing experience which provides people with both trauma and knowledge). The man tries to “rebuild” something. His heart? His body? His life? His faith? but he can’t do it, because it deteriorates instead. He’s told by people that that’s the routine of life, that’s what happens - death is real and will affect you, everyone experiences loss, you can’t do anything about it, but he doesn’t want to deal with it that way, he’s unable to come to terms with it.

VERSE 3

Now the speaker addresses the listener/reader. He tells us - “you” - that you can’t perform onstage when you drink too much. When a “star” is born something needs to die - he paraphrases the issue presented e.g. in Andersen’s tale “The Little Match Girl” where the protagonist is told by her grandmother that when somebody dies - a star falls from the sky. The speaker, possibly the author himself, knows the difficulty of being a known artist - drinking problems, the possible loss of one’s true identity which needs to “die” in order for their new image - “a star” to emerge, to please the audience. It doesn’t only need to refer to a musician/artist’s fate though, because one doesn’t need to be a singer to “perform” aka present, carry out, fulfill or accomplish anything. This verb may refer to any actions one can take, including the most basic ones. “Get too drunk” = make yourself unstable so you can’t do anything right. One thing also has to end in order for something else (sometimes better) to start. For us, for the speaker, for the author. For everyone. Later, the speaker clearly shows us his own perspective on the issues as he admits to having “spread his anger like Agent Orange”. Now, Agent Orange is a defoliant, most notably used by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War which caused major health problems for anybody who was exposed to it. By “spreading his anger” like a chemical the speaker confesses that he was open with his negative emotion in a toxic, contaminating and damaging way, to himself and other people, probably. He then admits that he did randomly, against the better judgment, as being “indiscriminate”, just like Agent Orange affecting the lives of Vietnamese people. He talks about how he met Lou Reed and Patti Smith (both valid counter-culture icons of the 70s, musicians and poets, self-taught and independent, charismatic) which didn’t have any crucial impact on him anyway. He thinks that yet another loss - of innocence, made him indifferent already. Also, you should never meet your heroes.

VERSE 4

Who’s a “she” mentioned at the beginning of the first line? That’s possibly the trickiest line of them all. A partner? A girlfriend? A mother? The aforementioned Innocence? She’s definitely known to the speaker and has the edge over him by “winning the fight”, possibly an argument or a game (like poker) by “calling his bluff” i.e. challenging the speaker to reveal his real intentions (like a card) to unmask him and show his weakness. “She” is smart and skilled. The speaker, as a result, runs away and notices the night has already begun. It is hot, too which can be unusual to some of the listeners since there’s no more sun at night thus the heat decreases. He points out that he has a lighter which doesn’t seem to work and admits that he shouldn’t smoke anyway. The lighter may symbolize the urge or possibility to do nasty things which never seem to work thus it’s better for the speaker to not continue on this path. He says he’s already on his way, “free to leave” as though he can go away already, not restrained nor limited anymore. He walks down the Bowery, fast. The Bowery is a street and neighborhood in New York City. The area was infamous for the number of low-brow concert halls, brothels, pawn shops and flophouses, welcoming all those considered outcasts or degenerates. This line can make the “she”-problem clearer then by adding more possible interpretations . A “she” can be a prostitute, an opponent in illegal poker game, maybe. The speaker cries and through his tears, yet another obstacle, he can’t see the road/path/way before him but he admits and assures us that he managed to get back home; to what’s familiar, close, near, comfortable and considered safe, known.

SUMMARY:

Conor Oberst’s “Next of Kin” tells a story of loss and acknowledgement of it. A story of feeling lost and inadequate, nervous and anxious. A story of failing at living with pain. A story of losing innocence, purity and dignity. A story of understanding loss, facing up to it and finding a way to what is always there, sometimes abandoned and neglected - home. Our own sensible selves.

#Conor Oberst#Bright Eyes#Ruminations#Conor Oberst lyrics#Lyrics analysis#Lyrics interpretation#Poetic analysis#Poetry interpretation#Poetry analysis#Poetic interpretation#2016#Song analysis#Song interpretation

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vayera

7 November 2020

18:5 Who is Avraham a servant to, strangers? Sounds a lot like the description of primitive societies where men gain power by either being physically violent, hospitable, or both. Avraham isn’t being hospitable because he’s a nice, moral guy—he’s being hospitable because he thinks the three strangers are going to build his power, and they are.

18:6 Who’s Sarah to be baking pitas when there are over three hundred people in Avraham’s household?

18:8 Not very kosher I see.

18:12 “Am I to have enjoyment with my husband so old?” Don’t you know that old folks are the horniest?

18:15 Sarah continuing the long tradition by now of straight-out lying to G-d? First Adam and Chava “we didn’t eat anything” to Cain “am I my brother’s keeper?” to now Sarah “I didn’t laugh”. What’s similar here, what’s different? And why do people keep doing it when they supposedly have faith in G-d?

18:17 G-d just monologuing like a cartoon villain here.

18:23 And Avraham arguing, as if G-d doesn’t know that he only cares about Lot being spared! Avraham couldn’t care less if a “righteous” person is saved, he just wants Lot to get out.

19:8 But okay, what? Both of Lot’s daughters are married... to men. Is Lot just lying to the Sodomites? Does he know that they won’t accept natives of Sodom to torture, but rather want to torture the strangers? Also, did Avraham warn Lot that angels were coming, so he had to treat them nicely, like he did? Or is Lot also such a good judge of character, like Avraham, that he can tell?

Brief tangent: in case anyone is unaware, Sodom and Gomorrah were not destroyed because of butt sex! For fuck’s sake. They were destroyed for being the most inhospitable, low-down, crooked scammers there ever were. Reference: the story of Hidod, the most absurd scammer in history.

Additionally, the crime of stinginess, wherein Ezekiel is quoted as saying “This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: arrogance! She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility, yet she did not support the poor and needy.”

19:14 Why could Lot’s sons-in-law not have just believed him? Why were they cursed, too? God promised to save ten people from Sodom, I’m only counting four!

19:19 Why does Lot not flee to the hills? Don’t you think that Zoar would be targeted before the hills, since it’s presumably nearer to Sodom than the hill country? Why does Lot say that “the bad” would overtake him in the hills? Is this a premonition of his daughters? They are 100% “the bad”!

19:31 These are like, super important and problematic women. Why don’t they have names?

19:34 There’s persuasion and lack of consent happening here, just like Chava and Adam with the fruit, and like Avram enslaving Sarai in Egypt. Avram, for instance, just proposed this plan and Sarai carried it out, but didn’t say “yes” to it ever.

20:2 You would think that Avraham would have fucking learned from the shit they pulled in Egypt would you not? Also, isn’t Sarah advanced in years and isn’t about to have sex with even Avraham? What’s the deal with that?

20:4 Yeah, this is really twisted. On the one hand, G-d is testing Avimelech, like he subsequently does with Avraham. Does that mean that G-d favors Avimelech? Well, clearly not like Avraham, because the penalty for failing the test isn’t spelled out as death for Avraham even beforehand.

20:9 But that’s the other hand: G-d is just going around threatening people for the entirely blameless things they’re doing just because Avraham is a fucking trickster and a scammer—the only difference between Avraham and the Sodomites is that the Sodomites are settled and mistreat the nomads, and Avraham is a nomad and mistreats the settlers!

20:12 “And besides, she is in truth my sister, my father’s daughter though not my mother’s; and she became my wife.”

20:14 Avraham is literally getting away with blackmail, and G-d literally just aided and abet him. G-d just has Avraham’s back, and Avraham knows it, and will just totally abuse and misuse that power.

21:9 “Playing” is the same word as “laughter”, which Sarah uses in 21:6... to literally name Yitzchak. There are interpretations of “metzahek” as committing sexual immorality, doing violence, or worshiping idols (the absurdity of which is the topic for another post) but it could also mean simply “mi-” (in) “yitzchak” (Isaac)! Sarah saw Yishmael’s influence on Yitzchak—possibly not even seeing Yishmael at all, but seeing Yitzchak—and got jealous. And her reaction to her jealousy was destructive and inhuman.

21:12 In which Avraham almost thinks a nice thought but G-d tells him to listen to his racist wife instead.

21:14 Shmot Rabbah is very anxious about how nice Avraham was to Yishmael and blames him for how wild Yishmael was despite the fact that it was literally foretold in prophecy. I’m very anxious about how “nice” Avraham was to Hagar because for fuck’s sake!

Also quick midrash break again—same Sefer HaYashar says that decades later, Avraham swung by Yishmael’s place to tell him to divorce his rude Egyptian wife for not giving him water and bread and marry a Canaanite instead.

0 notes

Text

Lamenting and Responding (and More)

Haven't written much in while, but I am repurposing this email/letter I sent Saturday to folks in the Christian Political Response group that I started back in 2017. It's audience is intended to be Christians, but it's non-exclusive and reveals some of my thinking.

How to process what we’re seeing in Minneapolis and elsewhere:

· Jonathan Walton and his Experiential Discipleship team at InterVarsity have put together a collection of foundational resources, including a Liturgy for the Lament of Racial Injustice and a document to help us process and respond to the murder of Ahmaud Arbery (sadly, tragically and infuriatingly, we’ve seen multiple more examples since).

· New Life Fellowship Church in Queens is hosting a Grace & Race Webinar on Thursday, June 4, from 6-8p ET. You can register here.

· Redeemer members and attenders may be interested in Redeemer’s Grace and Race Ministry’s statement on this subject here.

Reflections: I haven’t done a lot of reflective writing recently due to work and school commitments (and some laziness), but I wanted to put some things down on paper, so feel free to read or not, but these are my own thoughts, ideas and opinions on topics related to faith and politics. These are a bit hodgepodge, so I apologize in advance.

Qualified immunity: If there is a legislative or judicial policy change that could come out of the continued evidence of police brutality (often race-based), then it might be a roll back on qualified immunity protections. Though this wouldn’t do the heart transformation of the gospel, it would change incentives in a way that could save lives and protect civil rights. Qualified immunity is judge-made law that provides legal privilege for certain types of government officials (including police officers), which often makes it very difficult for victims of civil rights abuses at the hands of these protected officials to receive justice.

You can find calls to end qualified immunity from publications as politically diverse at The New Republic and National Review and two very different Supreme Court justices – Sonia Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas – have expressed problems with this legal doctrine. The Supreme Court is considering 13 different cases that involved qualified immunity and could announce as early as Monday that it will take up one or more of the cases (9 of the 13 cases involve police violation of civil rights, often violently, some lethally). Let’s pray the Supreme Court grants cert for these cases and considers them in good faith.

Putting yourself in scripture: In the Ahmaud Arbery link from Jonathan Walton above is an activity where we write ourselves into scripture, for instance, through psalms of lament. Related, The Park Forum published a devotional yesterday (recalling another post from 2018) called “How to Read Prophetic Judgment.” In it, John Tillman notes that we like to be the subject of comforting prophecy, but we put others in the path of afflicting prophecy. From Isaiah 30:12-13:

Because you have rejected this message,

relied on oppression

and depended on deceit,

this sin will become for you

like a high wall, cracked and bulging,

that collapses suddenly, in an instant.

It’s easy to interpret this passage in our time as judgment on the United States, judgment for the nation’s original sins and the inability of its espoused tenants (often built on lies) to overcome the sin that dwells deeply within it (book plug for 12 Lies That Hold America Captive by Jonathan Walton). That all may be true, but I fail to be transformed by the gospel when I refuse to admit that that I am the “you” in that scripture, that I have rejected this message and that my sin is like a high wall, cracked and bulging, that collapses in an instant.

I pray that we make sincere efforts to not assume that it’s all the bad people who are “you” – that they’re the ones being judged. G.K. Chesterton once was said have responding to the question, “What’s wrong with the world?” with the answer “I am.” This is the sort of humility that our discourse needs right now, and Christians are uniquely situated to provide it, but we fail so often.

On hypocrisy: Speaking of failing to live up to our standards or possibilities, I want to put in a good word for hypocrisy. I am well aware that Jesus makes a point of calling out the hypocrisy of the Pharisees (see Matthew 23). The Pharisees were espousing one set of virtues and then intentionally using those espoused virtues as a cudgel to oppress the poor and profit at their expense. That kind of hypocrisy is definitely bad, and even the hypocrisy I’m about to describe is certainly not good, but let me explain.

A hypocrite is someone who proclaims moral virtues while living a life that doesn’t match those proclamations. By that standard, we are all hypocrites. As Christians – and as humans – we all have deeply held beliefs about what’s good and right, and we all daily fail to live up to those virtues. Max Scheler was both an ethicist and a womanizer, and, when questioned about this hypocrisy, he argued that “the sign that shows the way to Boston doesn’t have to go there in order to do something useful for the rest of us.”

Obviously, the calling for a Christian is higher than the calling for a German ethicist. It’s not just good enough to say what’s right and to point to Jesus as the ultimate fulfillment of virtue and truth. We are also called to testify to our changed lives and the power of the gospel to do so. I fear, though, in this age when “authenticity” is considered superior to righteousness, that we who are wrapped up in our culture are too fearful to proclaim gospel virtues because we can’t live up to them. But when we mix our proclamation of virtue in the public square (and with friends, family and co-workers) with a humble testimony of failure and sinfulness, we can start to transform our culture. We see this powerfully modeled by Paul in Romans 7, and he was never one to shrink from the public square.

On news, disruption and truth: In an age of instantaneous reactions and viral videos (some of which give a one-sided depiction of events intended to provoke and enflame), I encourage us (and myself especially) to eschew the 24-hour news cycle, particularly if you’re finding that news reports are not driving you to scripture and prayer. Sometimes I obsess over being informed but just end up anxious and, while being anxious, getting a very shallow perspective of reality via social media.

This summer, our small group is reading a book by Alan Noble called Disruptive Witness, “disruption” being having a double meaning in reference to our disrupted, distracted lives and also the way we need to witness disruptively due to the post-Christian culture that many of our secular friends grew up in and have been hardened by. Saying no to a culture of disruption by avoiding the social media-driven news cycle is one way to be counter-cultural and also to bring your household some peace and calm.

There is one new outlet that I think demonstrates how to cover politics and current events without forsaking depth or succumbing to the pull of click-bait content. It’s called The Dispatch, and for those of you looking for some dissonance in your news (without the bad faith of FOX News), the conservative Dispatch might be a good place for you to find news analysis and political/legal podcasts. It’s run by men and women of good faith in a world where there are plenty of trolls and bad-faith actors, and I think it’s important that we have outlets like this, even if your politics don’t align with it. For instance:

· In his newsletters, David French gives a nuanced perspective on the complicated history of evangelicalism and abortion rights;

· French debunks some of the legal fallacies that led far-right Twitter to say that Ahmaud Arbery was killed in self-defense;

· In a podcast episode, foreign policy expert Thomas Joscelyn discusses U.S. foreign policy (especially in relation to China) with hosts Sarah Isgur and Steve Hayes.

Final words: If you made it this far, well, that’s surprising. I pray for safety for you and your family, for your transformation daily via the gospel and scripture, and I pray for our institutions – the family, the church, the government, the media, the academy and more – to be restored as formative places that seek the public good rather than self-serving platforms for personal aggrandizement. We’re very far from there. Lord help us!

0 notes

Link

KAIA SAND’S “Tiny Arctic Ice” is a wasteful poem: one line of poetry appears on each of the first 18 pages of her 2016 collection, A Tale of Magicians Who Puffed Up Money That Lost Its Puff. The poem’s paper-inefficiency makes its depiction of ecological crisis all the more unsettling. The poem begins:

Inhale, exhale 7.4 billion people breathing Some of us in captivity Our crops far-flung Prison is a place where children sometimes visit Jetted from Japan, edamame is eaten in England Airplane air is hard to share I breathe in what you breathe out, stranger

Breathing, an intimacy between strangers, guides an investigation of incarceration, agriculture and food transportation, and overpopulation on a plane or the planet. “Tiny Arctic Ice” diagnoses a planetary condition. It draws connections between the environmental, economic, and political systems. It makes the structural mundane, and the mundane structural. It blurs the line between human beings’ complicity with environmental destruction and their absorption of its consequences. “Tiny Arctic Ice” exemplifies a contemporary ecopoetics that articulates the sensorial and affective life of planetary disaster.

Angela Hume and Gillian Osborne, the editors of Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field (2018), theorize ecopoetics as both a critical practice and the poetic archive to which it attends. Ecopoetics, the corpus of poetry, can be grasped as an offshoot of midcentury US avant-garde movements (objectivism, Black Mountain poetry, New American poetry) that promote techniques like free verse, experiential aesthetics, and mixed-media pursuits. Although its trajectory periodically merges with that of ecological literary criticism or ecocriticism, ecopoetics, the critical practice, specifically resists a Romantic focus on pastoral and wildness in poetry criticism. This resistance intensifies in the last two decades of the 20th century, as ecopoetics evolves into an intersectional paradigm for evaluating the unevenly distributed effects of environmental degradation. Both creative and critical branches of ecopoetics depart from nature writing. Ecopoetics trades an Emersonian or Thoreauvian attention to sublime, untouched nature for sites of extraction, chemical spills, and other manifestations of ecosystemic violence.

In Recomposing Ecopoetics: North American Poetry of the Self-Conscious Anthropocene (2018), Lynn Keller locates ecopoetics in a period where human beings are aware of their impact on the nonhuman world. The Anthropocene, a geological era in which human activity has left an indelible planetary trace, may have begun centuries ago. By contrast, Keller argues that the “self-conscious Anthropocene” corresponds to a shorter period in which human beings have actively recognized the consequences of their actions on the Earth’s life-supporting infrastructure. The accession of a climate change denier to the US presidency and the defunding of the Environmental Protection Agency raise the question: How is the notion of the self-conscious Anthropocene altered when human beings refuse to recognize the planetary consequences of their actions? Keller’s periodization demands that we either see climate change deniers as self-conscious Anthropocene dwellers acting in bad faith, or count only some people’s — and really, poets’ — consciousness of human-caused climate change.

Keller’s initiative is in essence curatorial. Recomposing Ecopoetics might best be consumed as a series of attentive readings shedding light on the challenges of writing the Anthropocene. Juliana Spahr, Forrest Gander, and Ed Roberson, for example, show up in an illuminating essay on the problem of writing across experiential and phenomenal scales. Keller identifies two approaches to this problem. An aspirational approach jumps between molecular and planetary scales in a bid to think through intricate phenomena whose present-day manifestations recapitulate and reroute multimillion-year processes. For example, the project of visualization set up in the title of Roberson’s To See the Earth Before the End of the World (2010) relies on human beings’ existing ability to adapt to new scales of perception. Our current mental images of the Earth are the products of adjustments to technological innovations that include plane travel and space exploration. In awe of human beings’ perceptual flexibility, the speaker of Roberson’s “Topoi” asks,

… at what point did we become so familiar with

such long perspective we could look down and recognize the pile of Denver by the drop off and crumble of the plate up into the Rockies, or say That’s Detroit! by the link of lakes by

Lake St. Clair some thirty-thousand feet above Lake Eerie…?

Thinking across scales constitutes for Roberson an ability that must be cultivated and extended. The second approach to the problem of scale that Keller identifies is more skeptical. We cannot meet environmental challenges, the approach goes, simply by thinking at once about their small- and large-scale implications. Spahr’s “Unnamed Dragonfly Species,” from the collection Well Then There Now (2011), juxtaposes two complex environmental issues, global warming and species extinction:

Unnamed Dragonfly Species They were anxious and they were paralyzed by the largeness and the connectedness of systems, a largeness of relation that they liked to think about and often celebrated but now seemed unbearably tragic. Upland Sandpiper The connected relationship between water and land seemed deeply damaged, perhaps beyond repair in numerous places.

The poem goes back and forth between endangered species (in bold) and a quest for knowledge about climate change attributed to an obsessive “they.” Thinking across scales represents in Spahr’s poetry a locus of dissonance and alienation in the face of insurmountable environmental challenges.

Keller recruits poets such as Adam Dickinson, Jody Gladding, Jorie Graham, Jena Osman, Evelyn Reilly, and Angela Rawlings to tackle the long temporality of plastic degradation, interactions between human and nonhuman beings, apocalyptic discourse and its discontents, and the transformed sense of place of the self-conscious Anthropocene. One of the pleasures of reading Recomposing Ecopoetics comes from periodically revisiting poets, like Gander, Reilly, and Spahr, who recur throughout the chapters. Keller’s willingness to return to familiar figures suggests that neither their poetry nor its ecological significance is exhausted by her readings. Keller constructs, rather than extracts, a corpus.

¤

A narrower definition of ecopoetics appears near the conclusion of Margaret Ronda’s Remainders: American Poetry at Nature’s End (2018). For Ronda, the term designates a poetic sensibility that emerges in North American poetry in the early 2000s. This sensibility mobilizes figures of address, like apostrophe or prosopopeia, to configure human beings’ obligations to the nonhuman world — the paradoxical senses of intimacy and estrangement that characterize “differential responsibility” in the face of environmental destruction. A major item in Ronda’s microhistory of ecopoetics is the journal ecopoetics (2001–2009). The editor, Jonathan Skinner, imagined the publication as an antidote to avant-garde poetry’s “overall silence” on environmental issues. Whereas Language poetry had presumed that readers demonstrated agency by interpreting resistant or opaque texts, the journal ecopoetics asked how agency was compromised amid ecological turmoil.

The term “ecopoetics” designates only the most recent cluster of texts in a larger archive that Ronda frames as the poetry of the Great Acceleration. The Great Acceleration begins in 1945 with rapid, deleterious planetary changes, including a spike in CO2 emissions, biodiversity loss, and ocean acidification. Though many environmental shifts associated with the Great Acceleration precede 1945, the year marks the start of scaled-up capitalist extraction and expansion. Ronda further divides the Great Acceleration into three moments, investigated in the chronologically ordered chapters. The 1950s’ “Golden Age of Capitalism” occasions new kinds and scales of post-consumer waste as well as uneven urban and rural development. The 1960s and 1970s witness economic destabilization and the rise of a revolutionary politics that comprises an ecological agenda. And in the 2000s discourses of the Anthropocene prevail.

Paralleling Keller’s interest in an ecopoetics that considers nature writing now unsustainable, Ronda tracks adaptations to the obsolescence of an external concept of nature — nature that’s out there, beyond our reach. The end of nature doesn’t imply its wholesale disappearance. Nature is converted into traces or, in Ronda’s idiom, remainders. Adapted from Benjamin and Adorno, the concept of the remainder traffics between ecology, history, and form to capture remnants of capitalist circuits of production, circulation, and consumption. The remainder designates phenomena that range from the expected (emissions, toxic waste, and melting glaciers) to the more surprising (life in segregated neighborhoods, poetry itself).

Ronda’s expansive rubric of the remainder has the advantage of accentuating the ecological resonance of poems by figures not traditionally situated within ecological circles. Gwendolyn Brooks’s poetry, for instance, Ronda argues, “details how black lives in the postwar period were dictated by […] the ‘involuntary plan’ — urban restructuring and geographical circumscription of black neighborhoods, along with their accompanying environmental effects.” Yet Ronda absorbs all dynamics of inequality and oppression under economics. Brooks’s “poems, with their folk forms, detail an emergent history of racism and impoverishment as environmental conditions, a key dimension of the Great Acceleration,” she writes, subordinating anti-racism and environmentalism to a critique of capitalism. Ronda’s framing attenuates the intersectional potential of the environmental justice paradigm. Intersectionality reveals the concurrent operation of oppressive dynamics without claiming any given one as more significant, or worthier of our attention, than the others.

Though Remainders is more clearly driven by a literary-historical argument than Recomposing Ecopoetics, Ronda’s precise interpretations, above all else, dazzle. A member of Keller’s troupe, Juliana Spahr, also plays a principal role in Remainders. As Ronda puts it, Spahr’s 2004 poem “Gentle Now, Don’t Add to Heartache,” in which the word “nature” doesn’t once appear, unfolds as a meditation on the impossibility and unthinkability of nature in the 21st century. The speaker of the elegy embodies a tension between authorial agency and a negativity that lets everything in — nourishing resources as well as debris. The elegy derives its force from this unresolvable tension, from the “assertion of wishful and impossible reciprocity, expressed in the language of ineffable ‘heartache.’” Ronda doesn’t stop there: the author traces the evolution of Spahr’s mourning of nature since the 2000s. Spahr’s 2015 book That Winter the Wolf Came calls for a new poetics in response to the forms of communal intimacy that emerge, voluntarily or not, in the context of oil spills or state-sponsored violence. And “#Misanthropocene: 24 Theses,” a 2014 collaboration with Joshua Clover, is an exercise in self-critique. “#Misanthropocene” rebukes the “west melancholy” that anchors “Gentle Now.” It exposes the limited political reach of feeling bad about environmental destruction.

Ronda posits nature as a remaindered category of poetic thinking. A non-dominant cultural form, poetry might best represent what capitalism has spoiled. The analogy between poetic and natural remainders that determines Ronda’s choice of texts is original. Less convincing are the allusions to narrative’s representational inadequacy that show up in the book’s introduction. The author indicates, for instance, that the book’s objective is to attend “more fully to the forms and figures of ecological calamity […] than to narratives of sustainability and hope.” This claim fashions narrative into a straw man for teleology and affective homogeneity. It implies that atmosphere, ambience, and ambivalence are most fully realized in poetry and poetics — a provocation that more than a few experimental narratives of ecological calamity would complicate: Karen Tei Yamashita’s Through the Arc of the Rain Forest (1990), a magical-realist soap opera on the devastation of an Amazonian community; Richard Powers’s Gain (1998), a story of ovarian cancer in the shadow of the expansion of the soap corporation that might have caused the illness; and Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy (2014), a kaleidoscopic look at an unexplained ecological cataclysm. The list could go on.

One of Ronda’s crucial interventions is to recalibrate the political stakes of ecocriticism. “‘Green’ readings” have tended to stress environmental awareness and ethical actions. The poems Ronda considers, on the other hand, show the obstacles that environmental degradation poses to individual perception and ethical response. Take Barry Commoner’s invocations of air pollution in The Closing Circle (1971). As Ronda argues, they afford an index for the uncertainties involved in comprehending the exact causes and reach of environmental crisis. Keller also qualifies the political valence of the poems assembled in Recomposing Ecopoetics. “None of these writers imagine that poetry will save the world,” Keller specifies, “but their writing suggests a belief that poets have significant responsibility and a meaningful role to play in both considering and determining ‘what kind of world we will shape.’”

The writers who populate Keller’s and Ronda’s monographs don’t presume their authority or power in the project of reshaping the world. Keller and Ronda nonetheless teach us that an environmentally or ecologically attuned poetic practice, one that refuses to externalize nature, constitutes an expertise that this project can’t ignore. For decades, poets have tested out strategies for giving shape to the experience of mutated and mutilated ecologies and reflected on the stakes of doing so. As the path toward an ecologically sustainable future gets bumpier, poetic rhythm might at least afford environmental justice advocates some thrust.

¤

Jean-Thomas Tremblay holds a PhD from the University of Chicago. In the fall of 2018, they will serve as assistant professor of 20th- and 21st-century American fiction and film at New Mexico State University. Their writing has appeared in Criticism, Post-45 Peer-Reviewed, New Review of Film and Television Studies, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, Critical Inquiry, Public Books, Arcade, and Review 31.

The post No More Nature: On Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2K4dt9L

0 notes

Text

Red River Dialect Interview: Orange Blobs, Growing Together

Photo by Hannah Rose Whittle

BY JORDAN MAINZER

The recent story of folk band Red River Dialect is linear, but what story doesn’t have flashbacks or overarching themes? In May 2014, band leader David Morris started putting together what would become Tender Gold & Gentle Blue, an album inspired by both the loss of his father and, as he puts it, “things disappearing or not going my way.” The songs were developed over a long period and were acoustic guitar tracks that weren’t even supposed to be a Red River Dialect album. He asked his friend Robin Stratton, not in the band, to play bongos on some of the tracks. It sounded awful. Stratton suggested to try putting piano on the songs. It sounded great. Stratton joined the band, and Tender Gold & Gentle Blue was finally released over a year later when the various band members, all living in different places, had time to record.

Fast-forward to October the year after. Morris is trying to write a concept album about bells (what would become Broken Stay Open Sky). But the losses and disappointments that inspired Tender Gold were still populating Morris’ mind. So the album took a different shape, not born from a failure but instead a growth. And Red River Dialect continues to grow. When I spoke to Morris over Skype at the tail end of last year, he was at Stratton’s parents’ place, eating mince pies and jamming out new songs on a baby grand piano. “The album after [Broken Stay] is going to be more edgy and uptempo,” Morris said. “I feel like it’s going to be kind of different.”

Of course, Red River Dialect is very much also a product of its wide array of included instruments. Ed Sanders plays guitar, violin, banjo, and dulcimer. Simon Drinkwater plays guitar, harp, and electric guitar. Kiran Bhatt plays drums and various percussion. Coral Kindred-Boothby plays bass and cello. “Everyone’s got a peculiar style,” said Morris. In fact, some members have branched out from Red River Dialect. Kindred-Boothby has a solo record coming out later this year that Morris describes as one with “tape loops, singing, and strange, layered sounds.” And apparently Drinkwater’s a pretty incredible singer and songwriter himself. “He hasn’t released anything,” Morris said of his band-mate who he met at open mic nights. “But he’s got four of the best songwriter albums you could imagine on a hard drive.”

If you’re lucky enough to live in the UK, you can catch all of Red River Dialect at the Sea Change and End of the Road Festivals in August and September. This is their first time really touring with a full band, “even though we can’t afford it,” said Drinkwater. Since Broken Stay was recorded live, this will be the most faithful live adaptation of the songs yet, the main difference being that Morris will be playing electric guitar rather than acoustic guitar. Is there any chance the band might come stateside? “It’s hard to get 50 pounds per gig in England,” Morris said. “So coming to America is not realistic yet.” It costs 2500 pounds to just apply for a Visa, and bands have to prove that there’s a need for their music in America, according to Morris. “Hollywood Bowl haven’t called yet,” he said. “Neither has Pitchfork Music Festival.”

Read my interview with Morris, during which he breaks down Broken Stay Open Sky, below, edited for length and clarity.

Since I Less You: Did the sense of loss you experienced making Tender Gold & Gentle Blue resurface when your concept album “failed?”

David Morris: Yeah. It was more like having an idea of where you’re going, and then you set out on a journey towards that place, and other interesting things happen and you end up going somewhere else. Rather than, “I have to get there,” other ideas come in front of you in your reach.

I never held the idea of the themes really tightly. It was more that those images kept on coming up from what I was writing rather than the other way around. Obviously, when that process kept happening and I was aware of it, I wanted to follow and amplify it.

As I wrote in the [press release], I did decide that the Tender Gold album was the grieving album--done. I have to do something else. When writing the new songs on the new album, I was feeling like I’ve done that and have to do something different. But some of that stuff was still there, and I wasn’t as moved on as I thought.

In a sense, it was a case of not trying to make the songs conform to a pre-determined idea, but allowing them to come out the way they were. Which results in some stuff similar to the Tender Gold album.

SILY: So writing songs helped you realize your level of continual grieving. But it’s interesting to hear you talk about it as if you have zero semblance of disappointment that your original idea didn’t work out.

DM: No, there’s no disappointment. I think that for us to be able to make albums, it always feels like a triumph just to turn up in the same room together. It always feels like we pulled it off.

We all met a long time ago down in Cornwall. Now, we all live in somewhat different parts of the UK, so we don’t have the luxury of being able to play together as regularly as we would like. Those songs, I had been working on them, and the ideas were coming together. It always feels fortuitous that the songs end up turning into something at all and not just ideas or sketches. Sometimes, the idea of what you’re trying to make turns into something else. It’s better than having your expectations completely matched.

SILY: Why did you decide to open the album with an extended instrumental?

DM: I almost regretted that after the album was ready to go, because in a way, it’s like a connecting strand to Tender Gold & Gentle Blue. It’s almost a hint or a taste of the previous album. I think maybe it was an instrumental guitar piece before we added other things to it. I think opening with that is partly a connection or bridge, and then the other thing would be that it was like a little ceremony. Gathering the energy together before the songs start. There’s a sense that it kind of draws down the different instruments. It starts off quite fragile and then develops some kind of body. It’s a herald. Like the trumpets before something starts. Like someone’s arrived. It always went together with the song that follows it, “The View”, which is a song that could be played separately without the instrumental, but they always go together for me. It’s not like a palette cleanser, where someone gives you lemon sorbet in between courses. It creates a mood. Playing that puts me in a certain space of mind and makes me feel a certain way. It centers me, locates me, and brings my attention.

SILY: On “The View”, you sing, “I'm gaining confidence in the view now / The goodness of myself and others.” Is this you talking? In today’s world, that confidence can be pretty hard to come by. What does give you confidence?

DM: These [words] are from me. It’s definitely connected with meditation, for me. Through practicing meditation, there’s an aspect of beginning to experience that goodness rather than a conceptual evaluation. Rather than good vs. bad, touching in with the fundamental goodness of being. There being some kind of underlying connection in my own experience of the world. It’s possible to connect with that and develop my connection with that, and that makes it more possible to connect with other beings--not just humans--and society in general. Putting this song out there at the front--I find it provocative. I feel that I wanted to acknowledge that experience and that view without also engaging with the incredibly troubling aspects of our world. It would be quite false and delusional. That song is a bit of a proclamation. The statement of the chorus, when I get to the choruses, it’s like the fruition of what’s been in the verses before. It’s the compost of images from which the thoughts grow.