#I need to see it again in theaters the score was like the social network score on STEROIDS

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

still thinking about challengers that shit changed my brain chemistry

#literally has everything I could ever want in a movie#sports homoerotic friendship breakups zendaya trent reznor atticus ross techno score bisexuality insane camera work non linear chronicling#people's relationships over 10+ years#I need to see it again in theaters the score was like the social network score on STEROIDS#I can not express how much I was into this movie I left the theater feeling like I had just taken hard drugs#I LOVE MOVIES WE HAVE NEVER BEEN SO BACK!!!!!!!!!!!#enigma musings#film

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Down to Earth With Tyler Blackburn

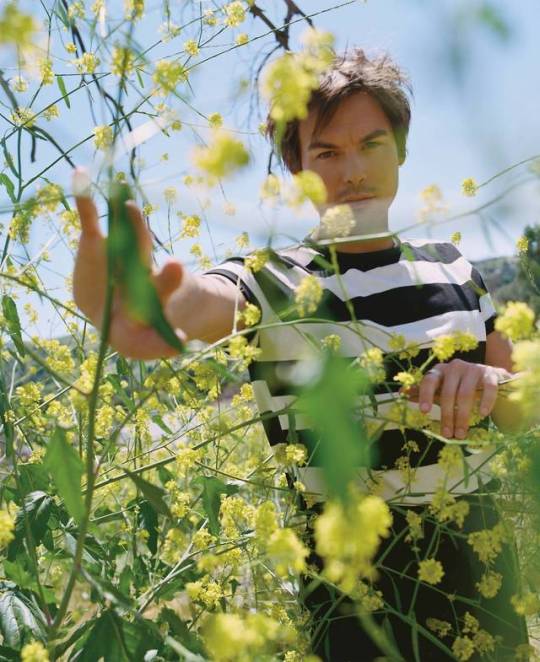

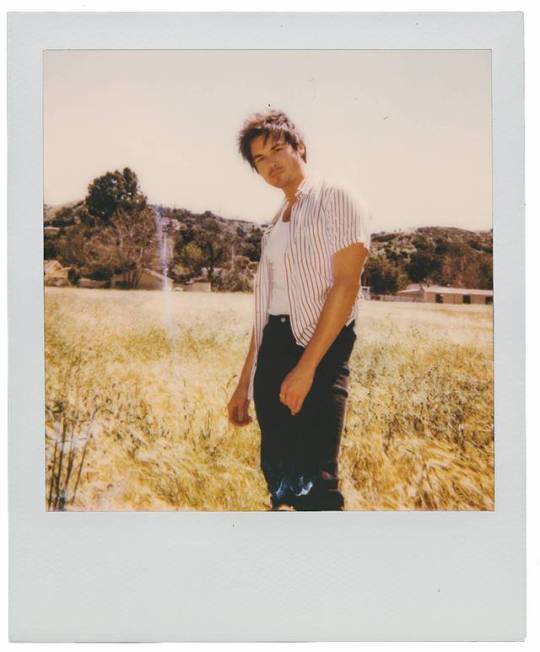

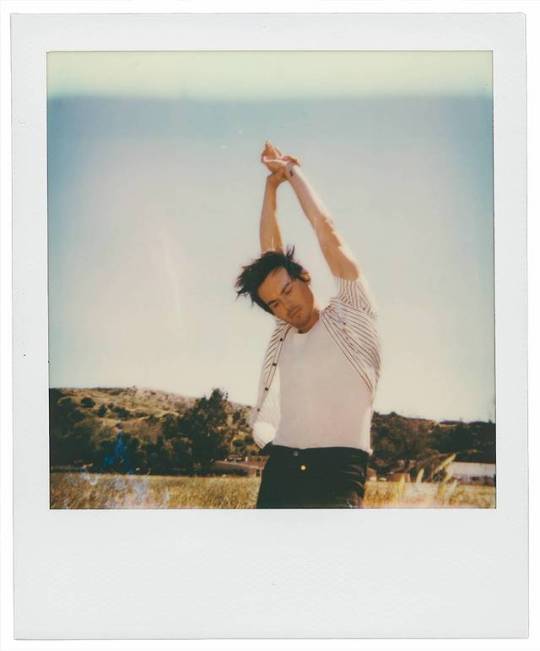

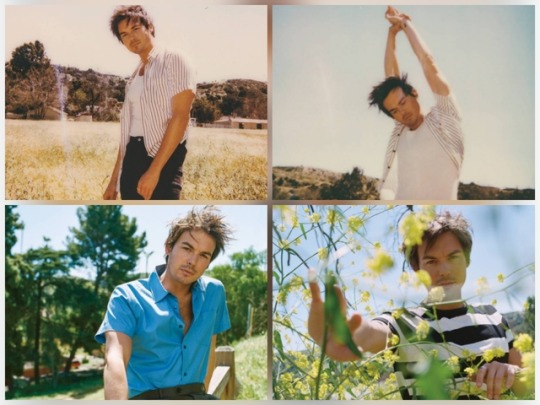

I‘ve never met Tyler Blackburn before—except that I have. Maybe it would be more accurate to say I’ve met versions of Tyler Blackburn. I’ve spent time with the actor on multiple occasions while covering his TV series Pretty Little Liars, the soapy teen-centered murder mystery that regularly generated more than a million tweets throughout its seven-season run. Just two weeks ago I reconnected with him in a lush meadow of flowering mustard outside Angeles National Forest, the site of his PLAYBOY photo shoot. But the Tyler Blackburn I’m meeting today at his home in the Atwater Village neighborhood of Los Angeles is in many ways an entirely different man.

When he greets me at the front door, Blackburn is relaxed, barefoot and still wearing what appears to be bed head. His disposition is unmistakably freer—lighter—than it’s been during our previous encounters. Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised by this. Six days earlier the 32-year-old actor came out publicly as bisexual in an online interview with The Advocate.

The announcement is clearly at the forefront of his mind as we sit down at his dining room table.

Almost immediately he starts to gush about the positive, and at times overwhelming, feedback he has received over the past few days. Within minutes he’s in tears. He tries to lighten the mood with a self-effacing quip, but now I’m in tears too. Then he tells me he can’t remember my question.

I haven’t even asked one yet, I reply.

“It just makes me feel, Wow, the world’s a little bit safer than I thought it was,” Blackburn says.

The most affecting response he’s received thus far has been from his father, whom Blackburn didn’t meet until he was five years old. Although he avoids offering any more details about that early chapter, he says, “Feeling like I’m a little bit different always made me wonder if he likes me, approves of me, loves me. He called, and it was just every single thing you would want to hear from your dad: ‘That was a bold move. I’m so proud of you.’ It was wild.”

Blackburn can’t pinpoint the exact moment he knew he was bisexual but says he was curious from the age of 16. It wasn’t until two years ago, though, that he decided to approach his publicity team about coming out publicly. At that point, Pretty Little Liars had wrapped, and the actor was without a job. So Blackburn and his team agreed they needed to hold off on making an announcement until his career was stable again. The lack of resolution weighed on him. “A year ago I was in a very bad place,” he says, adding that he has struggled with depression and anxiety. “I didn’t know what my career was going to be or where it was going. My personal life—my relationship with myself—was in a really bad place.” His casting on the CW’s Roswell, New Mexico, adapted from the same Melinda Metz book series as the WB’s 1999 cult favorite Roswell, seems to have come at the right time. Blackburn portrays Alex, a gay Army veteran whose relationship with Michael, a bisexual alien, has attracted legions of “Malex” devotees since the show’s January debut. Roswell, New Mexico has already been renewed for a second season—a feat for any series in this era of streaming, let alone one involving gay exophilia. Playing a character whose queerness has been so widely embraced by fans no doubt nudged Blackburn closer to revealing his truth for the first time since becoming an actor 15 years ago. (As he told The Advocate, “I’m so tired of caring so much. I just want to…feel okay with experiencing love and experiencing self-love.”) Still, he was somewhat reluctant. His hesitation was rooted in the fact that he wouldn’t be able to control what came next: the social pressures that often come with being one of the first—in his case, one of the first openly bisexual male actors to lead a prime-time television series. “If you stand for this thing, and you say it publicly, there’s suddenly the expectation of ‘Now your job is this,’ ” he says. “Even if someone’s like, ‘Now you’re going to go be the spokesperson’—well, no. If I don’t want to, I don’t want to. And that doesn’t mean I’m a half-assed queer.” Full disclosure: I previously wrote for a Pretty Little Liars fan site. In 2012 I published a listicle that ranked the show’s hottest male characters. Blackburn cracks up when I tell him this and wants to know whether he bested Ian Harding, his former co-star. After I inform him that his character (hacker with a heart of gold Caleb Rivers) finished second behind Harding’s (Ezra Fitz, a student-dating teacher) I promise to organize a recount. The always-modest Blackburn concedes that Harding is the rightful winner. (If anyone ever compiles a BuzzFeed article titled “Most Embarrassing Moments for Former Bloggers,” I’ll be offended if I’m not in the mix.)

Blackburn makes it clear that he has not always been comfortable with his status as a teen heartthrob. Knowing he was queer made it “hard to embrace it and enjoy it.” Growing up, he was bullied for being perceived as effeminate and was frequently subjected to slurs and homophobic jokes. He describes himself as a late bloomer who took longer than usual to shed his baby fat. He didn’t have many friends, nor did he date much in high school. A lifelong fan of musical theater and the performing arts, Blackburn signed with a Hollywood management company at the age of 17. His team at the time warned him that projecting femininity would hinder his success. An especially painful moment came after he’d auditioned for a role as a soldier and the producers wrote back that Blackburn had seemed “a little gay.” “Those two managers were so twisted in their advice to me,” Blackburn says. “They just said, ‘We don’t care if you are, but no one can know. You can’t walk into these rooms and seem gay. It’s not gonna work.’ I remember the shame, because I’ve been dealing with the feeling that I’m not a normal boy for my entire life.” After landing a recurring role on Days of Our Lives in 2010, Blackburn scored his big break when he appeared midway through the first season of Pretty Little Liars. “I was in Tyler’s first scene, so I got to be one of the first to work with him,” Shay Mitchell, who starred opposite Blackburn, tells PLAYBOY. “Right away, I knew he was special. Since the day I met him, Tyler always struck me as very authentic and very true to himself.” Fans instantly adored his on-screen love affair with Hanna Marin, played by Ashley Benson. The pair became known as “Haleb,” and Blackburn went on to win three Teen Choice Awards—surfboard trophies that solidify one’s status as a teen idol—in categories including Choice TV: Chemistry.

According to Blackburn, during the show’s seven years on the air, he and Benson bonded over their mutual distaste for the tabloid stardom that comes with headlining a TV phenomenon lapped up by teens. Today he fondly reflects on their on-camera chemistry. “It felt good,” he says. “It felt real.” Of course, rumors swirled that the pair’s romance was actually quite real. “We never officially dated,” he tells me. “In navigating our relationship—as co-workers but also as friends—sometimes the lines blurred a little. We had periods when we felt more for each other, but ultimately we’re good buds. For the most part, those rumors made us laugh. But then sometimes we’d be like, ‘Did someone see us hugging the other night?’ She was a huge part of a huge change in my life, so I’ll always hold her dear.” Blackburn also shares a unique connection with Mitchell outside their friendship. Similar to what Blackburn is now experiencing with Roswell, Mitchell was embraced by the LGBTQ community for playing a lesbian character, Emily Fields, whose same-sex romances on Pretty Little Liars were among the first on ABC Family (the former name of the Freeform network). Over the years, Blackburn had come out to select members of the Pretty Little Liars cast and crew, including creator I. Marlene King. But as the show approached its swan song, he started to recognize how hiding a part of himself was negatively affecting his life. He entered his first serious relationship with a man while filming the show’s final season. Not knowing how to tell co-workers—or whether to, say, invite his boyfriend to an afterparty—caused him to “go into a little bit of a shell” on the set.

“My boyfriend was hanging out with me at a Pretty Little Liars convention, and some of the fans were like, ‘Are you Tyler’s brother?’ ” Blackburn says. “He was very patient, but then afterward he was like, ‘That kind of hurt me.’ It was a big part of why we didn’t work out, just because he was at a different place than I was. Unfortunately, we don’t really talk anymore, but if he reads this, I hope he knows that he helped me so much in so many ways.” At that, Blackburn tearfully excuses himself and takes a private moment to regain his composure. “I never remember a time when I didn’t enjoy being with him,” says Harding, Blackburn’s former co-star. He says he saw the actor “start to become the person he is now when we worked together” but believes Blackburn needed to first come to terms with the idea that he could become “the face” of bisexuality. “Tyler’s discovering a way to bring real meaning with his presence in the world,” Harding says, “as an actor and as a whole human.”

Once the teenage Blackburn realized he was attracted to guys, he began “experimenting” with men while taking care not to become too emotionally attached. “I just didn’t feel I had the inner strength or the certainty that it was okay,” he says. It wasn’t until a decade later, at the age of 26, that he began to “actively embrace my bisexuality and start dating men, or at least open myself up to the idea.” He says he’s been in love with two women and had great relationships with both, but he “just knew that wasn’t the whole story.”

He was able to enjoy being single in his 20s in part because he wasn’t confident enough in his identity to commit to any one person in a relationship. “I had to really be patient with myself—and more so with men,” he says. “Certain things are much easier with women, just anatomically, and there’s a freedom in that.” He came out of that period with an appreciation for romance and intimacy. Sex without an emotional component, he discovered, didn’t have much appeal. “As I got older, I realized good sex is when you really have something between the two of you,” says Blackburn, who’s now dating an “amazing” guy. “It’s not just a body. The more I’ve realized that, the more able I am to be settled in my sexuality. I’m freer in my sexuality now. I’m very sexual; it’s a beautiful aspect of life.” Blackburn has, however, felt resistance from the LGBTQ community, particularly when bisexual women have questioned his orientation. “Once I decided to date men, I was like, Please just let me be gay and be okay with that, because it would be a lot fucking easier. At times, bisexuality feels like a big gray zone,” he says. (For example, Blackburn knows his sexuality may complicate how he becomes a father.) “I’ve had to check myself and say, I know how I felt when I was in love with women and when I slept with women. That was true and real. Don’t discredit that, because you’re feeding into what other people think about bisexuality.” He clearly isn't the first rising star who's had to deal with outside opinions of how to handle his Hollywood coming-out. I spoke to Brianna Hildebrand just before the release of 2018's smash hit Deadpool 2, and she explained that she had previously met with publicists who had offered to keep her sexuality under wraps, even though the actress herself had never suggested this. Meanwhile, ahead of the launch of last fall's Fantastic Beasts sequel, Ezra Miller told me that he's "been in audition situations where sexuality was totally being leveraged."

Fortunately for Blackburn, his recent experiences with colleagues have largely been supportive ones. He came out to Roswell, New Mexico showrunner Carina Adly Mackenzie when he first arrived in N.M. to shoot the pilot but after he had earned the role of Alex, which for him was the ideal sequence. "I think he takes the responsibility of being queer in the public eye very seriously, and waiting to come out was just about waiting until he was ready to share a private matter—not about being dishonest to his fans," Mackenzie tells PLAYBOY. "I have always known how important Alex is to Tyler, and I know that Tyler trusts me to do right by him, ultimately, and that’s really special." Blackburn finds it funny that he’s known for young-skewing TV shows; the question is, What might define him next? He’s grateful for his career, but he grew up wanting to make edgy dramas like the young Leonardo DiCaprio. He also cites an admiration for Miller, the queer actor who plays the Flash. “I most definitely want to be a fucking superhero one day,” Blackburn says a bit wistfully. His path to cape wearing does look more tenable. The day before his Advocate interview was posted, he booked a lead role in a fact-based disaster-survival film opposite Josh Duhamel. Blackburn jokes that his movie career was previously nonexistent, though his résumé features such thoughtful indie fare as 2017’s vignette-driven Hello Again. There, he plays a love interest to T.R. Knight, who tells PLAYBOY that Blackburn “embraces the challenge to stretch and not choose the easy path.” For now, Blackburn’s path appears to be just where he needs it to be. “I may never want to be a spokesperson in a huge way, but honestly, being truthful and authentic sets a great example,” he says. “To continue on a path of fulfillment and happiness is going to make people feel like they too can have that and it doesn’t need to be some spectacle.” As it turns out, he may already be a superhero.

- Playboy

#tyler blackburn#playboy 2019#tjb interviews#rnm cast#roswell new mexico#happy pride 🌈#god i love him

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

I absolutely love Tyler Blackburn

New article today

He is such a gem ❤

So genuine. Deserves all the love and support!

You can tell how much Alex means to him.

Please don't destroy this amazing character or this wonderful ship Carina!

It's a long read but well worth it

https://www.playboy.com/read/down-to-earth

❤

Down to Earth With Tyler Blackburn

The star of the CW's 'Roswell' reboot isn't a poster child of anything but his own path

Written by Ryan Gajewski

Photography by Graham Dunn

Published onJune 11, 2019

I’ve never met Tyler Blackburn before—except that I have. Maybe it would be more accurate to say I’ve met versions of Tyler Blackburn. I’ve spent time with the actor on multiple occasions while covering his TV series Pretty Little Liars, the soapy teen-centered murder mystery that regularly generated more than a million tweets throughout its seven-season run. Just two weeks ago I reconnected with him in a lush meadow of flowering mustard outside Angeles National Forest, the site of his PLAYBOY photo shoot. But the Tyler Blackburn I’m meeting today at his home in the Atwater Village neighborhood of Los Angeles is in many ways an entirely different man.

When he greets me at the front door, Blackburn is relaxed, barefoot and still wearing what appears to be bed head. His disposition is unmistakably freer—lighter—than it’s been during our previous encounters. Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised by this. Six days earlier the 32-year-old actor came out publicly as bisexual in an online interview with The Advocate. The announcement is clearly at the forefront of his mind as we sit down at his dining room table.

Almost immediately he starts to gush about the positive, and at times overwhelming, feedback he has received over the past few days. Within minutes he’s in tears. He tries to lighten the mood with a self-effacing quip, but now I’m in tears too. Then he tells me he can’t remember my question.

I haven’t even asked one yet, I reply.

“It just makes me feel, Wow, the world’s a little bit safer than I thought it was,” Blackburn says.

The most affecting response he’s received thus far has been from his father, whom Blackburn didn’t meet until he was five years old. Although he avoids offering any more details about that early chapter, he says, “Feeling like I’m a little bit different always made me wonder if he likes me, approves of me, loves me. He called, and it was just every single thing you would want to hear from your dad: ‘That was a bold move. I’m so proud of you.’ It was wild.”

Blackburn can’t pinpoint the exact moment he knew he was bisexual but says he was curious from the age of 16. It wasn’t until two years ago, though, that he decided to approach his publicity team about coming out publicly. At that point, Pretty Little Liarshad wrapped, and the actor was without a job. So Blackburn and his team agreed they needed to hold off on making an announcement until his career was stable again. The lack of resolution weighed on him.

“A year ago I was in a very bad place,” he says, adding that he has struggled with depression and anxiety. “I didn’t know what my career was going to be or where it was going. My personal life—my relationship with myself—was in a really bad place.”

His casting on the CW’s Roswell, New Mexico, adapted from the same Melinda Metz book series as the WB’s 1999 cult favorite Roswell, seems to have come at the right time. Blackburn portrays Alex, a gay Army veteran whose relationship with Michael, a bisexual alien, has attracted legions of “Malex” devotees since the show’s January debut. Roswell, New Mexico has already been renewed for a second season—a feat for any series in this era of streaming, let alone one involving gay exophilia.

Playing a character whose queerness has been so widely embraced by fans no doubt nudged Blackburn closer to revealing his truth for the first time since becoming an actor 15 years ago. (As he told The Advocate, “I’m so tired of caring so much. I just want to…feel okay with experiencing love and experiencing self-love.”) Still, he was somewhat reluctant. His hesitation was rooted in the fact that he wouldn’t be able to control what came next: the social pressures that often come with being one of the first—in his case, one of the first openly bisexual male actors to lead a prime-time television series.

“If you stand for this thing, and you say it publicly, there’s suddenly the expectation of ‘Now your job is this,’ ” he says. “Even if someone’s like, ‘Now you’re going to go be the spokesperson’—well, no. If I don’t want to, I don’t want to. And that doesn’t mean I’m a half-assed queer.”

Full disclosure: I previously wrote for a Pretty Little Liars fan site. In 2012 I published a listicle that ranked the show’s hottest male characters. Blackburn cracks up when I tell him this and wants to know whether he bested Ian Harding, his former co-star. After I inform him that his character (hacker with a heart of gold Caleb Rivers) finished second behind Harding’s (Ezra Fitz, a student-dating teacher) I promise to organize a recount. The always-modest Blackburn concedes that Harding is the rightful winner. (If anyone ever compiles a BuzzFeed article titled “Most Embarrassing Moments for Former Bloggers,” I’ll be offended if I’m not in the mix.)

Blackburn makes it clear that he has not always been comfortable with his status as a teen heartthrob. Knowing he was queer made it “hard to embrace it and enjoy it.” Growing up, he was bullied for being perceived as effeminate and was frequently subjected to slurs and homophobic jokes. He describes himself as a late bloomer who took longer than usual to shed his baby fat. He didn’t have many friends, nor did he date much in high school.

A lifelong fan of musical theater and the performing arts, Blackburn signed with a Hollywood management company at the age of 17. His team at the time warned him that projecting femininity would hinder his success. An especially painful moment came after he’d auditioned for a role as a soldier and the producers wrote back that Blackburn had seemed “a little gay.”

“Those two managers were so twisted in their advice to me,” Blackburn says. “They just said, ‘We don’t care if you are, but no one can know. You can’t walk into these rooms and seem gay. It’s not gonna work.’ I remember the shame, because I’ve been dealing with the feeling that I’m not a normal boy for my entire life.”

After landing a recurring role on Days of Our Lives in 2010, Blackburn scored his big break when he appeared midway through the first season of Pretty Little Liars. “I was in Tyler’s first scene, so I got to be one of the first to work with him,” Shay Mitchell, who starred opposite Blackburn, tells PLAYBOY. “Right away, I knew he was special. Since the day I met him, Tyler always struck me as very authentic and very true to himself.”

Fans instantly adored his on-screen love affair with Hanna Marin, played by Ashley Benson. The pair became known as “Haleb,” and Blackburn went on to win three Teen Choice Awards—surfboard trophies that solidify one’s status as a teen idol—in categories including Choice TV: Chemistry.

According to Blackburn, during the show’s seven years on the air, he and Benson bonded over their mutual distaste for the tabloid stardom that comes with headlining a TV phenomenon lapped up by teens. Today he fondly reflects on their on-camera chemistry. “It felt good,” he says. “It felt real.”

Of course, rumors swirled that the pair’s romance was actually quite real. “We never officially dated,” he tells me. “In navigating our relationship—as co-workers but also as friends—sometimes the lines blurred a little. We had periods when we felt more for each other, but ultimately we’re good buds. For the most part, those rumors made us laugh. But then sometimes we’d be like, ‘Did someone see us hugging the other night?’ She was a huge part of a huge change in my life, so I’ll always hold her dear.”

Blackburn also shares a unique connection with Mitchell outside their friendship. Similar to what Blackburn is now experiencing with Roswell, Mitchell was embraced by the LGBTQ community for playing a lesbian character, Emily Fields, whose same-sex romances on Pretty Little Liars were among the first on ABC Family (the former name of the Freeform network).

Over the years, Blackburn had come out to select members of the Pretty Little Liars cast and crew, including creator I. Marlene King. But as the show approached its swan song, he started to recognize how hiding a part of himself was negatively affecting his life. He entered his first serious relationship with a man while filming the show’s final season. Not knowing how to tell co-workers—or whether to, say, invite his boyfriend to an afterparty—caused him to “go into a little bit of a shell” on the set.

“My boyfriend was hanging out with me at a Pretty Little Liars convention, and some of the fans were like, ‘Are you Tyler’s brother?’ ” Blackburn says. “He was very patient, but then afterward he was like, ‘That kind of hurt me.’ It was a big part of why we didn’t work out, just because he was at a different place than I was. Unfortunately, we don’t really talk anymore, but if he reads this, I hope he knows that he helped me so much in so many ways.” At that, Blackburn tearfully excuses himself and takes a private moment to regain his composure.

“I never remember a time when I didn’t enjoy being with him,” says Harding, Blackburn’s former co-star. He says he saw the actor “start to become the person he is now when we worked together” but believes Blackburn needed to first come to terms with the idea that he could become “the face” of bisexuality. “Tyler’s discovering a way to bring real meaning with his presence in the world,” Harding says, “as an actor and as a whole human.”

Once the teenage Blackburn realized he was attracted to guys, he began “experimenting” with men while taking care not to become too emotionally attached. “I just didn’t feel I had the inner strength or the certainty that it was okay,” he says. It wasn’t until a decade later, at the age of 26, that he began to “actively embrace my bisexuality and start dating men, or at least open myself up to the idea.” He says he’s been in love with two women and had great relationships with both, but he “just knew that wasn’t the whole story.”

He was able to enjoy being single in his 20s in part because he wasn’t confident enough in his identity to commit to any one person in a relationship. “I had to really be patient with myself—and more so with men,” he says. “Certain things are much easier with women, just anatomically, and there’s a freedom in that.” He came out of that period with an appreciation for romance and intimacy. Sex without an emotional component, he discovered, didn’t have much appeal.

“As I got older, I realized good sex is when you really have something between the two of you,” says Blackburn, who’s now dating an “amazing” guy. “It’s not just a body. The more I’ve realized that, the more able I am to be settled in my sexuality. I’m freer in my sexuality now. I’m very sexual; it’s a beautiful aspect of life.”

Blackburn has, however, felt resistance from the LGBTQ community, particularly when bisexual women have questioned his orientation. “Once I decided to date men, I was like, Please just let me be gay and be okay with that, because it would be a lot fucking easier. At times, bisexuality feels like a big gray zone,” he says. (For example, Blackburn knows his sexuality may complicate how he becomes a father.) “I’ve had to check myself and say, I know how I felt when I was in love with women and when I slept with women. That was true and real. Don’t discredit that, because you’re feeding into what other people think about bisexuality.”

He clearly isn't the first rising star who's had to deal with outside opinions of how to handle his Hollywood coming-out. I spoke to Brianna Hildebrand just before the release of 2018's smash hit Deadpool 2, and she explained that she had previously met with publicists who had offered to keep her sexuality under wraps, even though the actress herself had never suggested this. Meanwhile, ahead of the launch of last fall's Fantastic Beasts sequel, Ezra Miller told methat he's "been in audition situations where sexuality was totally being leveraged."

Fortunately for Blackburn, his recent experiences with colleagues have largely been supportive ones. He came out to Roswell, New Mexico showrunner Carina Adly Mackenzie when he first arrived in N.M. to shoot the pilot but after he had earned the role of Alex, which for him was the ideal sequence. "I think he takes the responsibility of being queer in the public eye very seriously, and waiting to come out was just about waiting until he was ready to share a private matter—not about being dishonest to his fans," Mackenzie tells PLAYBOY. "I have always known how important Alex is to Tyler, and I know that Tyler trusts me to do right by him, ultimately, and that’s really special."

Blackburn finds it funny that he’s known for young-skewing TV shows; the question is, What might define him next? He’s grateful for his career, but he grew up wanting to make edgy dramas like the young Leonardo DiCaprio. He also cites an admiration for Miller, the queer actor who plays the Flash. “I most definitely want to be a fucking superhero one day,” Blackburn says a bit wistfully.

His path to cape wearing does look more tenable. The day before his Advocateinterview was posted, he booked a lead role in a fact-based disaster-survival film opposite Josh Duhamel. Blackburn jokes that his movie career was previously nonexistent, though his résumé features such thoughtful indie fare as 2017’s vignette-driven Hello Again. There, he plays a love interest to T.R. Knight, who tells PLAYBOY that Blackburn “embraces the challenge to stretch and not choose the easy path.”

For now, Blackburn’s path appears to be just where he needs it to be. “I may never want to be a spokesperson in a huge way, but honestly, being truthful and authentic sets a great example,” he says. “To continue on a path of fulfillment and happiness is going to make people feel like they too can have that and it doesn’t need to be some spectacle.” As it turns out, he may already be a superhero.

#tyler blackburn#roswell cast#roswell nm#alex manes#roswell new mexico#malex#roswell alex and michael

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

SCORE - research notes

SCORE: A FILM MUSIC DOCUMENTARY

Marco Beltrami - PIANO TUNES WITH THE WIND - MALIBU (LOOK INTO): Sound travels through the wire faster than the air, results in a reverse echo - no effect needed (find film used for) - The gunman - columba (instrument), intrigue - following a mystery,

ROCKY

Jon Burlingham, film music historian - Leonard something or other Bill Field, organist - Wurlitzer

MAX STEINER - king kong - orchestra music in a movie?? It completely changed the movie - what was before unexciting and studied became terrifying with the addition of music

ALFRED NEWMAN - horns and woodwinds - 20th century fox logo

David Newman - a flow, like speaking: it fluctuates

John Debney

James Cameron - spot session, trying to communicate the sound they hear in their heads, etc. - most directors don't know how to convert emotions into music, so the composer has to act as a 'therapist and go through the mish-mash

BEAR MCCREARY - try to figure out what their insecurities are first,

MERVYN WARREN

MYCHAEL DANNA

HANS ZIMMER - always the blank page,

RACHEL PORTMAN - change in the direction in the scene, often a prompt for when music will come in (quote);

CHRISTOPHE BECK -

Joseph Trapanese - invent a clever way of introducing something familiar

Motif - group of notes that might highlight what a film is (close encounters)

Beethoven - took a motif/theme, spin it out : 5th symphony

Simple hooks, feels like a pop song, casting them in different lights

HOWARD SHORE: "by using motifs, it helps you to understand the relationships in the story - when you hear a certain motif, you connect it, and it actually helps you follow the story." LOTR AS AN EXAMPLE "By the time you get to the end of the film, when you play that music in its full glory, it's already familiar to the audience. We're kind of building our way up to that main course."

ALEX NORTH - a streetcar named desire (background of ballets and shows - first film score incorporating jazz in writing)

The Pink panther,

JOHN BARRY - James Bond. Came from a band - band sensibility to movies,

big band was cool, swung, felt like a guy that could do anything - no spy/secret services without a reference to James Bond, just like Morricone with spaghetti westerns

ENNIO MORRICONE - Kill you with a melody - The good the bad and the ugly: guitar into the western environment - still the sounds of westerns 50/60 years later

BERNARD HERRMANN - THEME FROM VERTIGO: mystery - little phrases that circular madness to them that worked really well - everything driving you forward in a sick, disastrous way

psycho - tricked you into thinking you saw way more of the violent acts in the scene that actually occurred

TOM HOLKENBURG -

HEITOR PEREIRA

MARK MOTHERSBURG - rugrats on a toy piano

Any instrument is valid if it improves the music

Anything can be music

hurdygurdy - instrument

DARIO MARIANELLI

PARTICK DOYLLE

TRY TO FIND THE GENERAL RHYTHM IN THE SCENE - SEVEN MONTHS PRODUCING THE SCORE, DIFFERENT TYPES OF DRUMS (MAD MAX) - DRUMS UNIQUELY RECORDED, COMBINING TRACKS, AGGRESSIVE, - " don't care what it is, if I make a track, it has to i’ve me goosebumps myself"

"Goosebumps"

PROF. SIU-LAN TAN: different aspects of music are processed by systems in the brain - multifaceted - melody pitch, tempo and rhythm, -- physiological reaction - reward center, dopamine, react to music. Film music and orchestral music is of great interest to scientists because of it's ability to emote: film music isn’t something we pay conscious attention to and yet it has such a powerful impact on us - an audience's eyes can be drawn to different parts of the screen with music that matches certain characteristics being shown on the screen - for example a rising pitch with something that's rising: UP - first time we see the balloons - important visual motif and theme - interesting to see that music can be part of the choreography of our eye movements ET - Vast expansive music with the taking off of the space ship - go from big music to small - reminding us who's going into the spaceship, it's very sad, these are farewells - this fanfare that's very triumphant, saying we're looking at it from Elliot's view point, it's not a loss, it's almost like saying "Mission accomplished" - film music, so powerful, so un-captureable to scientists

QUINCY JONES - everything you see, you here (used to be) - eyes doing the same things the ear was doing

JERRY GOLDSMITH - planet of the apes: using modern techniques, reapplied it into drama - rubber balls being bounced in bowls, metal bowls, CHINATOWN - four pianos, etc. - ballsy

RANDY NEWMAN

JOHN WILLIAMS - jazz pianist - JAWS - crazy experiment - engine, accelerate - if we didn’t have that theme, we wouldn't know what was happening - spots and places music in the movie - only wanted music to announce the arrival of the shark STAR WARS - huge impact - theme - symphonic score, rediscovered the classical orchestral film score, good and bad, beautiful themes for romance and heroes, the Darth Vader theme - so marshal and broad - "oh boy there’s something not good here"; helps discern characters SUPERMAN theme - krypton theme: mysterious, av-ante garde, way of surrounding pieces with other pieces INDIANA JONES raiders of the lost ark - spends more time on those small bits of musical grammar so they seem inevitable - plethora of parts ET - film music has changed because film has changed, what it needs to do - end of ET - wide space of just music, JURASSIC PARK -

air studios - pick a studio ‘cus it's appropriate to the sort of sound you want to make - churches - haunted, etc. DAVID ARNOLD. - CASINO ROYALE - acoustics, choice - hundreds of mics - how close/how far you wanna feel from the music.

ABBEY ROAD STUDIOS - live sound, less absorbent material on the walls - great reverb, Beatles, Return of the Jedi, lord of the rings, mission impossible - different layouts for different sounds - Rogue Nation, changing music at different cuts to fix problems/change it up

film making styles have changed, so has film music

19702 - synthesizers and punk

DANNY ELFMAN - short musical ideas that become big musical ideas - Tim Burton, batman - only one rule: there are no rules -

THOMAS NEWMAN - difficult to develop what the sound it - like Danny elf man, developed his own sound - Shaw shank Redemption. American Beauty - marimba, sets the tone of the film, sets you a little off balance, captured the way of ding uncertainty - establish a key center, things will then weave in and around that baseline - creates a texture that lives behind the orchestra, yes could write orchestral scores, but sometimes a film needs something more intimate. prevailing mood, slap it on an image and let it sit for 2 minutes - cold, emotive piano

HANS ZIMMER: unconventional rock swagger to film screen - GLADIATOR - brutality, violence where the notes are placed, intensity - woman's vocals over the orchestra - shaped cinema - took the string section and made it like a guitar - they're playing rhythm - PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN - like led zepplin payed by an orchestra; DARK KNIGHT - blurred the line between giant symphonic and orchestral - constant pulse - powerful, exciting - INCEPTION - it's like a new morning, washes over you in waves, music just piles up - left with a big question.

People who aren't film composers being asked to make film scores - can bring so much authenticity to sound music - sounds are extremely contemporary - SOCIAL NETWORK - disturbing lyrical piano - human and technical, emotionally dark, - ATTICUS ROSS and TRENT RIZZLER

unconventional image and unconventional sound - so much greater than the sum of their arts beautiful chaos far more experimentation, freedom, Technology has made it possible for every composer to be a producer - at the core of it is the tune

STEVE JABLONSKY - Lockdown theme - first introduces french horns into the score, mixing them up a bit, bringing texture to the piece, you want your intention to be clear - the horns give it more of an emotional weight - you want to make sure the emotions you mean to grab the audience are strong enough, make bold statement

ALEXANDER BELSPATT

FOX STUDIOS - LA, stronger sound, London, softer sound -

HARRY GREGSON-WILLIAMS -

WARNER BROS. STUDIOS - JOHN (PAUL??) DEBNY -

music - the most human and emotive thing we have

ELLIOT GOLDENTHAL

BRIAN TYLER - if everything was perfect in music, everything would sound terrible - fast and furious 6 - you can feel when a cue is working the audience - goes to watch audience reactions when watching the movie, helps him for future films - get a sense of how did this work, do they scenes move people - will run into a bathroom stall, will see if anyone is humming or whistling the theme - feels like he affected them on a level they're not aware of -

TYLER BATES

MOBY - the one art form that doesn't technically exist - you can't put your finger on music - it's just air waves moving a little differently

Film music being used outside of film - Remember the Titans - Obama, whatever the audience felt in the theater was resonant again

HANS ZIMMER - LAST PEOPLE ON EARTH THAT FREQUENTLY COMMISSION ORCHESTRAL PIECES - WITHOUT THEM, ORCHESTRAL MUSIC WOULD DISAPPEAR, WOULD BE A CULTURAL LOSS TO HUMANITY, - we all have fragility, when i play you a piece of music, i completely expose myself, and that's a very scary moment - i love i love i love what I do -

music plays such an important role in a film

film music i one of the great art form of the 20th and 21st century

RYAN TAUBERT - SCORE

James Horner - titanic - sketch out on synthesizer

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exclusive: Greta Gerwig Talks Damsels in Distress, Personal Reinvention

By Brent Simon, April 21, 201.

source: http://www.shockya.com/news/2012/04/21/exclusive-greta-gerwig-talks-damsels-in-distress-personal-reinvention/

It’s no great knock on most actors and actresses to say that conversations with them, even when exceedingly pleasant, are often of the same genus, broadly speaking. After all, unless it’s a grand cover story for a print publication (a dwindling breed, it seems) such interviews are typically prescribed and tightly scheduled affairs, with the promotion of a specific project chiefly in mind. And if you don’t have much time, it can certainly be difficult to leave feeling that you’ve glimpsed a bit of who the interview subject really is.

But chatting with Greta Gerwig is an expansive experience, full of rich anecdotes, asides and pockets of intrigue. It helps, certainly, that she’s formally educated, having graduated from New York City’s Barnard College, where she studied English and philosophy. But it’s also in large part because of her easygoing nature, her lack of emotional or social guise. Her voice has a lilting quality that exudes thoughtfulness; Gerwig is not of the canned-answer clan, mindlessly reciting soundbite-friendly talking points. That her name is an anagram of great is no small surprise; it’s a fact that just seems right.

Gerwig’s latest film is writer-director Whit Stillman’s “Damsels in Distress,” in which she plays Violet, the quirky yet focused leader of a dynamic group of girls who set out to rescue fellow college students from depression through an on-campus suicide prevention center that peddles a combination of dance, donuts and hygiene improvement. Over breadsticks and iced tea, amidst sidebar discussions about college life and Andrew Jackson biographies, ShockYa recently had the chance to speak to Gerwig one-on-one, about “Damsels,” Stillman’s unique authorial voice, the Internet, personal reinvention, her thoughts on future life as a multi-hyphenate and why she’s still a certified aerobics instructor. The conversation is excerpted below:

ShockYa: So what was your first contact with Whit’s script?

Greta Gerwig: Well, I loved, loved, loved Whit’s movies. My friends and I from college used to do what we called the Chloe Sevigny from “Last Days of Disco” dance, where she just moved her shoulders. It’s not really a dance, I guess, but just a way she moved that looked really cool that we tried to emulate. So he was on that list of filmmakers that I would do anything to work with and for, and I was just so excited that there was a script and that he was going to make something. I thought that maybe he just had made three perfect films and was done. Along with everyone else, I had no idea what he was doing. It was like that feeling you get at the end of a movie that you just adore, where you just wish there was more of it — you want to keep living in that world, and you wish someone would say, “There’s another one right here.” Or [it’s the same] way I feel about writers I really love, where I’ll read a book and say, “Thank God, they have seven other books, I’m occupied.” It was that feeling of (excitement) over him having more characters and ideas, so I was enthralled and taken in by that at the outset. I don’t even really remember reading it with a particular character in mind, although I know that when we met he saw me as Lily. But I just read it like a book or a play that I was studying, I wasn’t reading it to see if I could play a certain part, necessarily.

ShockYa: Whit’s films are so urbane and particular that feel like they should come with footnotes, so I was surprised to learn that he doesn’t really like to have rhapsodic discussions about historical or philosophical or social commentary in his films.

GG: Whit doesn’t really encourage any sort of intellectualizing or mythologizing of his own work, especially on set. He’s very dismissive about all of that, he’s very quick to say, “Oh, I’m stupid,” which is obviously not true. I mean, I think… well, we didn’t specifically talk about them with Whit, but the ideas that he puts forth, as you learn the script and say the lines, you come to think that they make a lot of sense and are really rational. The process of getting inside a character and why they say these things, you inevitably believe all of the things that they’re espousing on some level. At least I do, I don’t know if everyone does. (laughs) When I first read the script I thought, “Oh, what a funny and ridiculous idea,” but by the end of shooting I thought, “No, that’s totally reasonable, people actually are happier when they’re dancing.” Even though he didn’t specifically sit down and talk about the decline of decadence and all of that, it all works its way in there if you just say it enough.

ShockYa: He also has a very specific pitch and meter to his dialogue. Did he talk about that a lot?

GG: Not per se. He wouldn’t give us specific direction regarding sound, but I would say the big thing for me, because I had such an idea of other people doing his dialogue, was getting those voices out of my head — like getting Chris Eigeman out of my head, or Kate Beckinsale out of my head. I didn’t want to be doing an imitation of the way they sounded when they did his dialogue, which is what I think what happens a lot with writer-directors with a very strong voice. In their later films, when people know what they’re doing, it’s what happens in Woody Allen films where they do an imitation of him. But when he was making films in the 1970s people weren’t doing imitations of what they thought it was. I think sometimes when things become iconic, the rhythms get set in a way that’s hard to break out of. The big thing for me was that I tried to come at it internally. It’s so tempting when you get a big monologue to score it almost like a musical score, and say, “Here’s the first thought, here’s the next,” to block it off and underline operative words and really prepare it because it’s a large chunk of text. But I tried to almost memorize it without meaning beforehand, and then find the meaning as I’m making my point to another person, so that I didn’t do this intellectual rhythmic process before, which would have been based on what his other actors had done. I tried to find the words spontaneously based on the thought pattern, if that makes sense. (laughs) Other people may do other things.

ShockYa: You mentioned Woody Allen, [and you’re in his] next film (“To Rome With Love”). Other films have proxy Woody Allens; is that part of your segment in “To Rome With Love” at all?

GG: Not in my role. I don’t think the female characters are usually written as a proxy for him, so there’s less of a trap to fall into. I’m with Jesse Eisenberg, Alec Baldwin and Ellen Page. It was great, and a lot of fun. It’s really funny, and definitely one of his comedies — less along the lines of “Match Point” or “Vicky Christina” and more like “Midnight in Paris.”

ShockYa: One of the things that struck me about “Damsels” was its idea of radical conceptual reinvention, and that we accept that in artists, like Madonna or Lady Gaga or whomever, but less so in everyday life, from our friends and peers. Did you ever experience that feeling as you moved out of adolescence, a desire to shed a skin, if you will?

GG: I’ve always had the desire to get to the most authentic version of myself, whatever that means, and I’ve harbored some misplaced belief that there is an authentic version and I’m not there. I think it’s now more popularly accepted in psychology that we have many selves that are true selves, and depending on the occasion you’re one way at work and another way at home. You are adaptable and they’re all you. But I find the time that I have felt most pulled toward reinvention has been more with the stuff that happens outside of acting — dressing up for the premieres or doing that kind of stuff. That all feels like I need to transform Greta into something else, and I don’t feel that I’ve been successful at doing that, nor does it make me very comfortable.

ShockYa: Does that feel like a need?

GG: No. I used to (even) be worried about things like drinking too much coffee because I thought it altered my personality, so the Madonna transformation or something like that makes me nervous. I don’t have that architect’s view of myself. I think some filmmakers have that, actually — they design themselves and their lives, and look a certain way. They want to change or invent a persona as a way of protection.

ShockYa: I think Hollywood is like that in a lot of respects. A big part of it is the entertainment industry, yes, but it’s also a destination city with so many people constantly moving in and out.

GG: Not to get too heady about it, but it feels like everyone is famous now, in the sense that everyone is documenting themselves really heavily. When I was in college, which was from 2002 to 2006, Facebook happened and I was at Columbia and we all joined because it was exclusive. Like, that montage in “The Social Network”? That totally happened to me! It was really funny to watch it, because it was my life being dramatized in a (David) Fincher movie, and I didn’t even have to go through a serial killer experience. But for me I think the most extreme version of reinvention I’ve gone through is just a honing of tastes. In college it was (about discovering) good movies, music, books and theater, and feeling a little bit ashamed about your high school CD collection and hiding it, but then in your mid-20s owning it again. That’s a whole process. Now I think that people are so aware of their persona and what they’re putting out there, and have a need to micromanage their own image. Even if you’re not a so-called public person it’s so part of life now, I think everyone is their own Madonna.

ShockYa: I do sometimes think that social networking and the ubiquitousness of connection is re-wiring the human brain a bit, because it’s depriving it [of needed] downtime.

GG: I read this article about Facebook where Zadie Smith had written a piece in the “New York Review,” and it was her musings on stuff technological, and she said that all these things that we take for granted have a mind and a creator behind them, and the key thing to know about Facebook is that it was basically made by an adolescent boy — these are [the things] that he thought was important. So then you filter your entire identity into the categories that an adolescent boy thought were important at one time — like, a smart adolescent boy, but one nonetheless. There’s another example that I thought was really cool. It’s not quite as poignant, but I thought how it’s hard to imagine how a computer would work if there weren’t folders. That’s such a part of how we think about and use computers — but that’s not the way it has to be, that’s just the way it is. These things become invisible because they’re so accepted. But I think the whole idea of invention depends on a viewer, and someone looking at you and setting up a situation where people are looking at you. I mean, I love it — I think it’s so strange and extreme and great — and I think Whit loves artifice too. I mean, I know he does; I don’t feel uncomfortable saying that. I think he would appreciate the well-told lie, I don’t think it’s something that he finds upsetting. It’s almost like this enjoyment of the surface, but that doesn’t have to be shallow or trite. It just is this sincere enjoyment of the surface.

ShockYa: Are you big on social media, then?

GG: No, I’m not on Facebook or any of that stuff. But I do think about it a lot. I’m very interested in it. I don’t think anyone has really written anything great about it yet, in an academic way that’s also accessible to a lot of people. Like, I re-read “On Photography,” this (Susan) Sontag book recently, and I don’t think there’s an equivalent for the Internet and what’s happening now. She’s so smart about photographs and the way they’re utilized. She points out such smart things, about how you can’t imagine a modern family without photographs, and how photography is a part of the family, part of what that glue is. It’s part of the government, and it’s hard to imagine being on vacation anymore without photography. I just feel like someone needs to take a really intellectual look at the Internet. I feel like some people have written really smart things about it, but almost from a scientific point-of-view — like what is this in relationship to your brain? [There hasn’t been] a look at the paradigm shift that’s happening. I think there are things that have been touched upon — I read that (Nicholas Carr) book “The Shallows,” which was pretty good but didn’t go far enough, I thought — and someone needs to do it. You could really make some statements about some stuff. It’s odd — I participate so little in that world, and yet I’m so interested in what somebody will say about it because I think it’s huge. And I also think it’s funny that with “Damsels” we made this movie about college which basically has none of that stuff at all. I think it’s because Whit doesn’t really use [social media] either.

ShockYa: Because your route to acting was a little bit different than a lot of other younger actors, which is something I think comes through regardless of which movies someone might have seen you in —

GG: (laughs, interrupting) OK! That’s great. (laughs) It’s funny, because I just wanted people to see me as an actor at one time, I was so sad that I (thought it) would never (happen). I love writing and doing those things, I’m totally happy. But it was that moment of identity (crisis) where I was like, “I wish I could just be an actor and have everyone see that.”

ShockYa: What age was that?

GG: Twenty-five. (laughs)

ShockYa: See, that’s what I’m saying — that’s relatively late. Regardless of skill or attributes, I think there’s a particular thing — and I’m not knocking it, because it’s understandable for actors raised on pilot season auditions or television shows — that often comes through in performers who have a few more years of life experience, or who aren’t thrust into a bunch of studio films at a very young age.

GG: I wouldn’t trade college for anything, it changed my life. And I also think it’s an opportunity to exist — well, it’s not outside of the economy, because it is very expensive — but the work you do there is outside of the economic world. Most of your life is spent doing things that are directly engaged with a consumer economy. You’re either making something for consumption or buying shit, or your life is formed around that. It’s idealized, and it costs money to be there, so it doesn’t totally work (as an example), but spending 18 to 21 or 22 not doing anything that’s actually useful — or making, buying and selling at that moment — is I think spiritually rich and important. Even though it’s not religious, I think the time spent reading books because they’re great and talking about them because they’re great is valuable, because there’s more to life than utility. And that’s probably a reason why I love Whit’s movies so, because he’s so a part of that mindset and the way that he views the world. And even though he makes fun of pseudo-intellectual characters, they still are so smart and funny — like in “Metropolitan,” with the reading of the book reviews and what not. (pause) If I could be only an actress and that be that work then I would do it, but it doesn’t really work for me. (laughs) I hate saying “just an actor,” I don’t like that implication, but… it’s just not the whole thing for me.

ShockYa: Do you think you’ll end up back behind the camera? {note: Gerwig co-directed 2008’s “Nights and Weekends”}

GG: Yeah, I think that’s totally where I’ll end up. And I’m satisfied knowing that it may not ever be one thing. It may be a combination of things. I might be happiest doing lots of stuff.

ShockYa: I remember on a certain level having a profound jealousy of the founding fathers, because of this idea of [their very] scattered intellectual interests.

GG: Yes! It’s the best. I always think of them, and the issues of people who did everything. Not to sound like a communist, but because everything is so monetized today and everyone is so trained for what they do that I feel like it’s hard to elegantly take something up. Because there’s always a school for it, or whatever — a specialty. The ability to be a dabbler and an amateur takes a lot more…

ShockYa: Because people always want to know: to what end?

GG: Yeah, to what end. Like, why does that matter? But I love people who dabble. I read a lot, and spend a lot of time trying to learn foreign languages, which I’m not good at. I’m not a natural, but I really love them and also I got this idea in my head since Kristin Scott Thomas acts in French films and speaks French really well. I thought, “Oh, how brilliant!” and because I really like Arnaud Desplechin, (I thought) maybe if I become really good at French I can be in one of his films. But I also like a lot of Korean films right now, and Korean is so hard! (laughs) So I have tons of those audio programs. I download them — they’re the Pimsleur method, where it’s listen-and-repeat. I also try to play the trumpet. And I also write scripts. But I’m not a good cook, even though I want to be — I think that’s a nice thing to know how to do, in theory. But the hilarious thing about the founding fathers is that they were, like, amateur architects! (laughs) Do you know what I mean? That’s some serious dabbling: “I just picked up draftsmanship.”

ShockYa: Right. “I’ll just design my own home.”

GG: Oh, and I’m also certified in a lot of weird jobs, because in high school I had an idea that I wanted to be an actor or writer, and that I might not get paid, so I thought I’d become good at all these lower-level jobs that I wouldn’t have to take all that seriously. So I’m a certified aerobics instructor and I’m a certified paralegal, and also one other thing… (pauses) what was it?

ShockYa: Not taxidermy?

GG: (laughs) No, not that. But I got good at jobs that weren’t mentally taxing or intense, because I was a bad waitress. I realized I was really terrible, and figured out there were other jobs that I needed to learn how to do. I think it’s at the end of “David Copperfield,” where he learns shorthand (laughs) — that’s like the thing that makes his life works out. I always thought that was such a funny detail in that book, like that the shorthand allowed him to go to night school or something. I feel like characters in (Charles) Dickens books always make me feel lazy. (laughs) They work so hard. I don’t see myself designing a house anytime soon, but… maybe. I’m only 28, I guess there’s still time.

0 notes

Text

Opening titles: commercials that sell a series

The art of the opening title sequence is flourishing like never before. The best ones contain clues, “Easter eggs,” as to the theme of path of the series. I’ve collected some examples below.

I’m constantly on the lookout for new and interesting TV series. We live in a golden age, where I’d rather stay home and watch ten hours of deeply-plotted long form television than go to a movie theater and watch two hours of made-for-the-masses light entertainment. TV networks are trying to outdo each other in making niche content that new customers can discover over time, and a lot of that niche content appeals to me. It’s smart, it’s complex, and it’s very, very human.

Recently I found myself watching the Starz series The Missing. There are two series of ten episodes each, and I plowed through both of them within a couple of weeks. Each series is told non-sequentially, jumping forward and backward in time, and a lot of the drama comes from seeing how “before” differs to “after” but not knowing how the differences came to be. Over time, though, each of the differences is explained as the mystery slowly unravels.

Initially I thought the opening title sequence was a melange of arbitrary images, but as the series progressed I realized that each image was a clue as to where the story was going.

Beyond that… well, before I go any further, you should watch some footage. Here’s the series two trailer:

Both series are about child abductions, and combine family drama (how families function after such a loss) with a complex mystery that has many intertwining threads.

Here’s the series two opening title sequence:

Not only is each image a clue to what happens later in the series, but most are displayed as visual memories held by the abducted child. They capture hints of the emotional highs and lows of someone torn from their family environment and thrust into a new dynamic that, for them, becomes completely normal. The style in which this sequence is shot is not at all like that of the series itself, but it’s completely appropriate to set the stage for what’s to come. And, if you watch carefully, you’ll see some elements from the trailer that are presented in the title sequence, but from a child’s point of view.

As the threads of the mystery come together the opening titles become more and more satisfying to watch.

(The Missing is available on Amazon Prime Video.)

Another series I’ve written about lately is Patriot. This Amazon Prime original series is one of my favorite shows of all time. It’s very dark, very funny, very emotional, and very complex, with some action tossed in for good measure. It took me a few episodes to figure it out, but the title sequence takes on new meaning once one gets the gist of the series:

Patriot is ultimately a story about family. Dad works in a very shady position within the U.S. intelligence community, taking on jobs that need doing but require official deniability. One son, who isn’t quite as worldly as his brother and, while lovable, is a bit goofy and naive, is a U.S. congressman. The other son, the one with a wild side, has been groomed to be a deniable asset: he gets his hands dirty, often with blood. Both effectively work for their father, but out of family obligation rather than official obligation.

Maybe I’m reading more into this than I should, but as the series went on I got the feeling that the title sequence was about the father grooming his sons to become what they became, especially the wilder of the two. This makes perfect sense, as—by the end of the series—it’s clear that dad is using this son without much concern for his health or safety, although he has complete confidence in his skills.

Best of all, the actual “Patriot” title card changes to reflect some aspect of the upcoming episode. I love touches like that: they assume that the audience is bright enough to catch on, and will get some additional satisfaction out of connecting the dots that fall beyond the most obvious dots.

Here’s another opening title sequence, from one of my favorite series, that sums up the subject matter very well:

The show is officially about a traveling carnival during the Great Depression, where the supernatural is simply a part of everyday life and everyone seems to have a destiny to fulfill, for good or evil. There were certain elements that felt familiar, though, and it became clear when reading a retrospective of the series where the executive producer/creator said that it was the Book of Revelations played out in the 1930s Dust Bowl.

What a crazy and original premise for a series, but it worked amazingly well. It’s one of the creepiest series around, with great performances by all concerned, and rich, deeply emotional story lines. Unfortunately it only lasted for two years out of a planned five, as the production costs were quite high and it never really found an audience. (It was truly ahead of its time, as it was riding the transition between factory television and the new wave of niche television.) HBO agreed to renew the series in return for budget cuts, but the show had an ensemble cast and there was no one to cut.

This sequence clearly sets the stage for a series about destiny (the tarot cards) and the battle between good and evil, as shown through various stock footage clips that demonstrate that this battle isn’t as abstract as we might like. Best of all, the camera leads us to each clip by traveling through an appropriate tarot card.

Continuing the theme of HBO creating great series with amazing title sequences, one of my favorites is from The Leftovers. This series, which examines the social, political and spiritual repercussions of an event in which 2% of the world’s population disappears without a trace or explanation, is really about loss, and the idea that anyone could lose anyone at any time. It’s also about the risks of falling in love, knowing that what happened before could always happen again.

The series one opener had a somewhat religious and mythological slant, but the series two opener was simple, brilliant and summed up the theme of the series perfectly:

I don’t know who thought about snipping people out of photos, but it’s both insidious and brilliant all at the same time. It’s a great metaphor for the series, which is not an upper by any stretch of the imagination but is one of the best dramas I’ve ever seen on television.

Lastly, a bit of fun. The BBC series Neverwhere doesn’t hold up terribly well after 20 years, and even at the time it was clear it didn’t have a terribly big budget, but the opening titles hold the distinction of being scored by Brian Eno. The sequence doesn’t reveal much about the series other than to see the stage for high weirdness, as it is about a magical London that exists underneath and adjacent to modern London, that the modern residents can’t (or don’t want to) see. (It was inspired when the author, Neil Gaiman, noticed that people ignored the city’s homeless population as if they were invisible.)

Every title sequence is effectively a commercial for the content that follows, and the best of them present us with riddles to solve, or reveal underlying themes that we only become aware of as the stories progress. I find that astoundingly satisfying, and I encourage the better series to keep up the great work and the others to step up their game.

Art Adams Director of Photography

The post Opening titles: commercials that sell a series appeared first on ProVideo Coalition.

First Found At: Opening titles: commercials that sell a series

0 notes

Text

R. Creative Investigation – collated quotes

Style.

“my aesthetic has always-sort of been tied to…the story became the context for the lighting and the lighting became the context for the story at the same time.” (Film school commentaries, 2013)

“Finchers sleek, symmetrical symmetry [in the girl with the dragon tattoo] echoes the work of one of his idols, Stanley Kubrick. Here, the camera glides forward, in the style of the shinning.” (Vice, 2016)

“The shooting of [The Girl with The Dragon Tattoo] in full frame, and the later addition of a wide screen matte in post production, is a testament to Fincher’s need for control, this method allows him to compose the fram exactly as he wants.” (Beyl, 2015)

“I just love the idea of omniscience the camera goes over here perfectly, and it goes over there kinda perfectly and it doesn’t have any personality to it, it’s very much like what’s happening was doomed to happen. - David Fincher” (Zhou, 2014)

“Every Ime you go to a close-up the audience knows: “Look at this, this is important.” You have to be very, very cauIous and careful about when you choose to do it. - David Fincher” (Zhou, 2014)

“I wanted to present, in as wide a frame, and in as unloaded a situaIon as possible, as much of a kinda simple proscenium way, this is what’s going on, this is what this guy sees. -David Fincher” (Zhou, 2014)

‘First proposed by Francois Truffaut in the 1950′s…the auteur theory set out to provide such a critical tool…acknowledging that film is a collaborative art, then goes on to argue that when a film reveals a thematic and stylistic coherence, that coherence can usually be attributed to the guidance vision of a single artist.’ (Grant, 2008)

“Fincher’s signature is immediately apparent [in The Social Network], once again utilising high contrast lightning and using pracIcal lamps which make for dark…interiors.” (Beyl, 2015)

“For one thing, handheld. Fincher is a locked-down put-it-on-a-tripod filmmaker. He hates handheld and does it maybe once per film. Dragon Tattoo has two scenes, while Zodiac has one, and The Social Network has only [one] shot. Se7en has the most handheld of any Fincher film: five scenes.” (Zhou, 2014)

Themes

“The film’s portrayal of an entirely corporatized world devoid of alternatives to entrepreneurial life, in which the Secretary of the Treasury acts as the President of Harvard and starting a business is the main point of college life, is pointed. (During the three-week rehearsals that predated shooting, in which Fincher, Sorkin, and the principals sat under a quotation from a critic excoriating Fight Club for being “anticapitalist” and “anti-society,” Fincher opined: “This college experience is not about ‘it’s all open to you be- cause you got into Harvard’—that was all a lie.”)” (Tyree, 2011)

‘before we accuse David Fincher of sexism himself, note that the director shows Nick slamming Amy’s head against the wall after she tells him she’s pregnant, a scene which drew an audible gasp from the theater I was in even though Affleck calling her a “bitch” drew laughs minutes before.’ (Dockterman, 2014)

“Fincher and Sorkin pack this masterly film with layers of sly ironies: as the technology of communication flourishes” (Sandhu, 2010)

“Aside from Aaron Sorkin’s dialogue fireworks, i would say that its appeal is down to the narrative’s gripping relationship to something we all worry about” (BFI, 2011)

Collaborations

“the red one is 9lbs when you put a lens on it, 14lbs…on the social network i have to film these tiny boats…i cant add 13lbs a camera on the side, it’ll topple the boat...you’ve gutta take one, you’ve gutta bore it out, what ever you have to do, you’ve gutta figure out a way, you’ve gutta give me the indy car version of the RED one” (side by side, 2012)

Aaron Sorkin’s fast-paced, witty screenplay works through flashbacks, using as its frame the conflicting court-room testimonies from the law-suits which besiege Zuckerberg once Facebook has become a success.” (Sandhu, 2010)

“Reznor, Ross, and Fincher have culIvated a symbioIc relaIonship that…elevates any project they undertake into a darkly sublime experience.” (Beyl, 2014)

“in this scene [of the social network] fincher uses tight close ups to turn Aaron Sorkin’s dialogue heavy script into a claustrophobic thriller” (Vice, 2016)

“Fincher understands the power of images, and he has a repetition of pushing his collaborators to the limit in order to create them - ‘David has the taste of an artist and a mind of an engineer’ - Ben Affleck” (Vice, 2016)

‘Very few writers are creating complex, evil female characters with interesting motivations. Gillian Flynn is. It seems sexist to assert that female characters ought to be, at their core, loving and good.’ (Dockertman, 2014)

‘I think Flynn likes that complication: she and Fincher have constructed a movie that forces the audience to debate and pick apart its gender dynamics. There’s no question that Amy is a monster’ (Dockertman, 2014)

‘At times carrying echoes of their work on “Social Network,” Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ score blends dread with driving momentum, establishing a richly unsettling mood with recurring dissonances, eerie wind chimes and pulsating reverb effects.’ (Chang, 2011)

‘With the outstanding assistance of d.p. Jeff Cronenweth and production designer Donald Graham Burt, Fincher has rendered a gray, vividly creepy world in keeping with Larsson’s cynical vision’ (Chang, 2011)

‘The position of the camera was chosen by the director…and by the cinematographer. The action was designed in the first place by a team of screenwriters. The editor juxtaposed the shot with others that enhances the impact.’ (Grant, 2008)

“Unlike Anderson, Tarantino, and Nolan, Fincher has never been credited with writing any of his films, forgoing the more hands-on method of catering a project to one’s own tastes.” (Simonpillai, 2014)

“his entire body of work is consistent with the development of an auteur. While Fincher’s new hotly anticipated, best-seller adaptation has Gillian Flynn as its author and screenwriter, it seems as though she wrote it in a David Fincher state-of-mind.” (Simonpillai, 2014)

0 notes