#I make either eclipse references with albus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

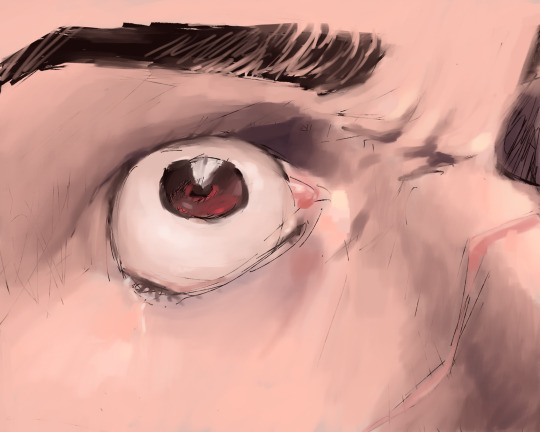

Thought it high time to give Albus the dramatic art treatment!

#I make either eclipse references with albus#or i really focus on his eyes#sometimes even both!#i'm annoyed at myself for at least not recording a timelapse of this one because i thought it came together really nicely at the end#nessart#digital art#digital artist#artists on tumblr#digital fanart#fanart#goodboyaudios#gba bastard warrior#gba bvz

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albus Dumbledore: The Religious Leader in Harry Potter

So, I have recently had a relatively old post reblogged by someone who decided to ask me what my ‘textual’ sources were for my statement that Dumbledore is a good example of a religious zealot that basically runs a group of fanatics who follow him. As I felt this to be a good thing to ask me, I was initially calm and considered this a reasonable thing to ask, until I reached the point where they specifically state that if I can’t provide such textual sources then they’re ‘going to assume that you build your opinion off of Tumblr posts and fanfiction and I’m gonna laugh at you for thinking those are reliable sources.’

Now, perhaps I may be a tad bit rude and impolite here but, unless they work on the assumption that everything is clearly shouted out very loudly and clearly in all fiction, then I’m afraid the explicit textual sources they’re demanding are likely to not exist; the art of understanding a novel lies in reading between the lines after all. However, I’m going to be polite and retain my modicum of mature reasoning and not laugh very loudly at such a sweeping statement – working on the assumption that fiction writers don’t think through what they create is, unfortunately, a common assumption in this world and one I have little time or respect for.

Now that’s been said, perhaps it’d be best to get onto the ‘textual’ sources I’ve been requested to provide.

Note: I am using the original Harry Potter books I had bought for me mere days or hours after each was released so page numbers may differ for each edition and where they were published (mine are UK publications). Just in case anyone thinks I’m making references up.

I’m going to approach this in much the same way I approach anything that is a multi-layered question: by breaking it down and tackling each section individually. First off – Albus Dumbledore’s background.

[Read More]

Who is Albus Dumbledore and What is His Background?

I am stating this outright now that I am making use of the HPwiki since it has the most consistent and referenced information about Dumbledore that won’t require me specifically hunting through Pottermore or the books just to give a general overview of one of the most well-known and popular characters in Rowling’s magical world. If this isn’t considered by some to be a reliable source then apologies, but this is what I’m using to give you a summary of Dumbledore’s background and his numerous achievements.

According to the HPwiki, Dumbledore officially held the titles of; Grand Sorcerer, Supreme Mugwump, Chief Warlock of the Wizengamot and Headmaster of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. In addition, he was also the leader and creator of the Order of the Phoenix. The son of Percival and Kendra Dumbledore, Albus was a half-blood (like the other two main characters in the trio of powerful wizards that the Harry Potter series revolves around; Harry and Voldemort). It is my assumption that, due to the imagery that Rowling evokes when Harry, Ron and Hermione visit Godric’s Hollow to see the grave of Harry’s parents and they discover a grave for the Dumbledore’s with an engraving of the Death Hallows (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, p.267), as well as the fact that Sirius states that all wizarding families are related in some way:

‘The pure-blood families are all interrelated…If you’re only going to let your sons and daughters marry pure-bloods your choice is very limited; there are hardly any of us left. Molly and I are cousins by marriage and Arthur’s something like my second cousin once removed. But there’s no point looking for them on here – if ever a family was a bunch of blood traitors it’s the Weasleys.’ (Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, p.105)

While this doesn’t necessarily cover families with muggle-born and muggle heritage, it does infer that Albus too was related to most other wizarding families. Adding the fact that Albus was obsessed with the Deathly Hallows from a relatively young age, and the sign of the Deathly Hallows on a Dumbledore grave, then you theoretically can argue that he could have theoretically been related to the Peverell family: a family that died out in the male line as Hermione states in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in chapter twenty-two:

‘The only place I’ve managed to find the name “Peverell” is Nature’s Nobility: A Wizarding Genealogy. I borrowed it from Kreacher…It lists the pure-blood families that are now extinct in the male line. Apparently the Peverells were one of the earliest families to vanish.’ (pp.346-7)

Note: Whether or not this is accurate and whether or not this is simply my own personal perception of Dumbledore’s lineage, the fact still remains that theoretically speaking, the Peverell family can be linked to at least some of the wizarding families of Britain as per Rowling’s own statements in her series.

Moving on from this potential relationship and the fact that these arguably provide some evidence for my initial comment about Dumbledore: ‘he comes into the Magical World from a long-standing magical family with age-old connections with a shit tonne of political power’. While I will agree that his family history doesn’t necessarily mean Dumbledore began with political power amassed by his family – unlike, for example, the Malfoy family or the Blacks – there is still the fact that his father, Percival Dumbledore, was either a pure-blood or a half-blood himself, thereby suggesting that he may have had some connection to the Ministry of Magic of Great Britain. Even if this were not the case, considering the fact that Dumbledore can at least be considered a half-blood with some magical lineage from pure-blood ancestors, he would have been in a more advantageous position, politically and social speaking, than muggle-borns in the magical world.

Continuing on, we are informed in The Deathly Hallows of Dumbledore’s connection with Gellert Grindelwald (pp.290-1). It is during this introduction that we also discover that, at one point, Dumbledore believed in much the same as Grindelwald in regards to the rights of wizards over muggles:

‘Your point about wizard dominance being FOR THE MUGGLES’ OWN GOOD – this, I think, is the crucial point. Yes, we have been given power and, yes, that power gives us the right to rule, but it also gives us responsibilities over the ruled. We must stress this point, it will be the foundation stone upon which we build. Where we are opposed, as we surely will be, this must be the basis of all our counter-arguments. We seize control FOR THE GREATER GOOD. And from this it follows that where we meet resistance, we must use only the force that is necessary and no more. (This was your mistake at Durmstrang! But I do not complain, because if you had not been expelled, we would never have met.)’ (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Letter to Gellert Grindelwald from Albus Dumbledore, p.291)

The above quotation lends support to my own statement in the original post that Dumbledore is ‘friends with a blood purist (Grindelwald)…[because] if you’re friends with someone like that then, on some level you agree with them.’

Ultimately, Dumbledore’s background lends itself to the initial starting blocks for the development of a saviour complex – most especially when we consider the fact that he ‘failed’ his sister and mother (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, p.292). While a ‘saviour complex’ (or messiah complex) is not a diagnosis nor a clinical term, it can however be connected to delusions of grandeur; it is quite obvious that in his correspondence with Grindelwald, Dumbledore seems to believe them both to be acting in a similar manner to those who feel that they have a duty to others, a responsibility, that means they must ‘save’ others – in this case, it can be argued that Dumbledore is functioning under the belief that he must save wizarding kind from muggles, and the muggles from themselves:

‘You cannot imagine how [Grindelwald’s] ideas caught me, Harry, inflamed me. Muggles forced into subservience. We wizards triumphant. Grindelwald and I, the glorious young leaders of the revolution.’ (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, p.573)

The attack on his younger sister Ariana by muggle children, and the subsequent imprisonment of his father for attacking them in retribution, provides Albus’ character with the beginning points to have a measure of hatred, or disdain towards muggles; it also provides a point where he can begin to perceive wizards are requiring protection from muggles and muggles of being unable to handle themselves – again this would be compounded if you consider that Albus was born at the end of the nineteenth century, on the cusp of the Great War and when colonialism was still at its peak.

For the Greater Good

Moving on, we come to the point where I state that Dumbledore takes on ‘an almost mythical status’ due to his ‘amazing magical power and the fact that he defeats a Dark Wizard without resorting to similar Dark Magic to do so’. While this isn’t precisely new information, nor an incorrect statement, it does bear some supporting evidence in order to reaffirm it:

‘In a matter of months, however, Albus’s own fame had begun to eclipse that of his father. By the end of his first year, he would never again be known as the son of a Muggle-hater, but as nothing more or less than the most brilliant student ever seen at the school.’

‘He not only won every prize of note that the school offered, he was soon in regular correspondence with the most notable magical names of the day, including Nicolas Flamel, the celebrated alchemist, Bathilda Bagshot, the noted historian, and Adalbert Waffling, the magical theoretician. Several of his papers found their way into learned publications such as Transfiguration Today, Challenges in Charming and The Practical Potioneer. Dumbledore’s future career seemed likely to be meteoric, and the only question that remained was when he would become Minister for Magic. Though it was often predicted in later years, that he was on the point of taking the job, however, he never had Ministerial ambitions.’

‘Other quills will describe the triumphs of the following years. Dumbledore’s innumerable contributions to the store of wizarding knowledge, including his discovery of the twelve uses of dragon’s blood, will benefit generations to come, as will the wisdom he displayed in the many judgements he made while Chief Warlock of the Wizengamot.’

‘They say, still, that no wizarding duel ever matched that between Dumbledore and Grindelwald in 1945. Those who witnessed it have written of the terror and the awe they felt as they watched these two extraordinary wizards do battle. Dumbledore’s triumph, and its consequences for the wizarding world, are considered a turning point in magical history to match the introduction of the International Statute of Secrecy or the downfall of He Who Must Not Be Named.’

(Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, pp.22-24)

Each of these quotations support the initial statement I made as to the strength of Dumbledore’s magical ability and the fact that his defeat of Grindelwald enabled him to attain an ‘Otherworldly status’. There are numerous characters throughout Harry Potter who treat Dumbledore’s word as law – inadvertently echoing Christian parallels that Rowling herself has stated the series has; one popular concept is that Dumbledore is a metaphor for God or Death (MTV, 2007).

I state, at one point, that the members of the Order, place Dumbledore ‘above them to such a degree that his every action is revered and accepted as “for the greater good” or because he “knows best”’ and this is something I strongly stand by. In truth, however, not every action undertook by Dumbledore is revered or accepted willingly, there is a growing measure of bitterness in Sirius Black’s opinion on Dumbledore’s decisions in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, but, for the vast majority, they generally accept Dumbledore’s word and do not truly act to question or undermine it in any way (Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, p.84). This could be construed as faith or trust in someone who has earned such respect, but there is the matter of the way in which Dumbledore is presented throughout the series up to the point of Voldemort’s return – after which the Ministry of Magic, led by Cornelius Fudge, seeks to undermine his authority through a combination of public smears and the stripping of official positions within the Ministry itself:

‘“They’re trying to discredit him,” said Lupin. “Didn’t you see the Daily Prophet last week? They reported that he’d been voted out of the Chairmanship of the International Confederation of Wizards because he’s getting old and losing his grip, but it’s not true; he was voted out by Ministry wizards after he made a speech announcing Voldemort’s return. They’ve demoted him from Chief Warlock on the Wizengamot – that’s the Wizard High Court – and they’re talking about taking away his Order of Merlin, First Class too.”’ (Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, p.90)

Contrary to the belief that there is only one reference to ‘the greater good’ in regards to Dumbledore’s actions, there are, at least three. These three references are present in the last book of the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows:

‘He died as he lived, working always for the greater good and, to his last house, as willing to stretch out a hand to a small boy with dragon pox as he was on the day that I met him.’ (p.24)

‘Your point about wizard dominance being FOR THE MUGGLES’ OWN GOOD – this, I think, is the crucial point… We seize control FOR THE GREATER GOOD. And from this it follows that where we meet resistance, we must use only the force that is necessary and no more. (p.291)

‘I assuaged my conscience with empty words. It would all be for the greater good, and any harm done would be repaid a hundredfold in benefits for wizards.’ (p.573)

In an interview with Evan Solomon (2000), Rowling stated that she enjoyed writing Dumbledore’s character because he ‘is the epitome of goodness’ which, in my personal opinion, suggests that perhaps Rowling is unaware of the duplicity and the dichotomy present in her portrayal of Dumbledore. It is obvious that she planned for Dumbledore to be a figure worthy of sympathy and pity in the final book, but also one that was highly complex and multi-faceted – both marks of skilled writing and character development. However, this does not preclude the reality that Dumbledore’s actions and the way he is viewed by numerous characters in the series, do correspond with more fanatic actions and behaviours of religious leaders.

Fanaticism: What is it and How does it apply to Dumbledore?

The philosopher George Santayana (1905) provides a definition of fanaticism that I find quite apt and amusing in its presentation; fanaticism is the ‘redoubling [of] your effort when you have forgotten your aim’ – to be a fanatic is to belief quite stridently but to lack an accurate direction for that belief to travel.

Lehtsaar (1997) defines fanaticism as ‘the pursuit or defence of something in an extreme and passionate way that goes beyond normality’ with religious fanaticism further defined by ‘blind faith, the persecution of dissents and the absence of reality’ (p.9). It could be argued that this definition is in a way, inaccurate to apply to Dumbledore however, in an abstract manner it is not.

As Postman (1976) states, ‘the key to all fanatical beliefs is that they are self-confirming… (some beliefs are) fanatical not because they are “false”, but because they are expressed in such a way that they can never be shown to be false’ (pp.104-112).

In regards to historical events of religious fanaticism, one doesn’t need to look much further than the vast majority of European history – most especially in regards to Christianity. As Selengut (2008) in Sacred Fury: Understanding Religious Violence, points out that the Spanish Inquisition was largely the monarchy’s attempt to maintain Catholic Christianity as the dominant religion: ‘The inquisitions were attempts at self-protection and targeted primarily “internal enemies” of the church’ (p.66). What is of significance in regards to their entire discussion, can be explained in the following quotation from Selengut (2008):

‘The inquisitors generally saw themselves as educators helping people maintain correct beliefs by pointing out errors in knowledge and judgement’ (p.66, italics added)

It is this that characterises much of the fanaticism seen in regards to Dumbledore and his Order of the Phoenix. At the end of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Dumbledore is faced with the knowledge that Voldemort has returned to his former strength; this knowledge is rejected by the Minister for Magic, Cornelius Fudge, and Dumbledore’s response to contact Order members from the last war immediately. The Order then is in a similar position to the inquisitors in Selengut’s description – they see themselves as individuals who must correct incorrect beliefs with their knowledge and judgement, guided by Dumbledore.

Gall, Charbonneau and Florack (2011) in a recent study found that individuals who were the most committed to attending church found it the most difficult to cope through being tested for breast cancer (a stressful, trying experience even when a diagnosis is not given). In regards to church attendance, in most cases this includes inclusionary activities such as the community-aspect of church attendance, and often correlates with adherence to religious rules and laws. Utilising this research as support for the behaviour of Molly Weasley in the Order of the Phoenix, it is quite clear that her ability to cope successfully with the highly stressful experience of being part of the Order – which her children attempt to join repeatedly, in some cases succeeding – is highly dependent on how the degree of faith she has in the Order and Dumbledore specifically:

‘“Well,” said Mrs Weasley, breathing deeply and looking around the table for support that did not come, “well…I can see I’m going to be overruled. I’ll just say this: Dumbledore must have had his reasons for not wanting Harry to know too much”’ (Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, p. 85)

Of course, the reverse is also true in respects to church attendance. Dukes (1964) found that church attendance correlated strongly with increased responsiveness to placebos, and in a study by Walters (1957) it was found that those who were highly dependent on alcohol were significantly more likely to have a religious background, thus suggesting that religious individuals are dependent not only on social values but external agents as well. Therefore, it could conversely be argued that Molly Weasley isn’t necessarily an example of religious fanaticism – although she does repeatedly express intense faith and trust toward Dumbledore – but rather a more general example of a woman who relies on her faith in others in order to function, including in her support system external systems of control and regulation that, when they directly counter her faith in Dumbledore, results in an extreme stress response.

Dumbledore is an Addict: The Fanaticism of the Deathly Hallows

In the final instalment of the Harry Potter series, we are introduced to the Deathly Hallows; three magical artefacts are incontestable strength and ability, which are sought after by some wizards in order to obtain ‘mastery’ over Death.

Peele and Brodsky (1975) provide a definition of what addiction is: ‘a person’s attachment to a sensation, an object, or another person…such as to lessen his appreciation of and ability to deal with other things in his environment, or in himself, so that he has become increasingly dependent on that experience as his only source of gratification’ (p.168). While it can obviously be pointed out that Dumbledore does not spend every moment of his life obsessing about the Deathly Hallows, there is textual evidence that he spent at least a significant amount of time interested in them:

‘The Hallows, the Hallows…a desperate man’s dream!’

‘Master of death, Harry, master of Death! Was I better, ultimately, than Voldemort?’

‘I, too, sought a way to conquer death, Harry’ (Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, p.571)

‘It was the thing, above all, that dew us together [the Hallows]… two clever, arrogant boys with a shared obsession. He wanted to come to Godric’s Hollow, as I am sure you have grasped, because of the grave of Ignotus Peverell. He wanted to explore the place the third brother had died.’

‘I could hardly believe what I was seeing. I asked to borrow it, to examine it. I had long since given up my dream of uniting the Hallows, but I could not resist, could not help taking a closer look…It was a Cloak the likes of which I had never seen, immensely old, perfect in every respect…and then your father died, and I had two Hallows at last, all to myself!’ (p.572)

‘At the heart of our schemes, the Deathly Hallows! How they fascinated him, how they fascinated both of us! The unbeatable wand, the weapon that would lead us to power! The Resurrection Stone – to him, though I pretended not to know it, it meant an army of Inferi! To me, I confess, it meant the return of my parents, and the lifting of all responsibility from my shoulders… Invincible masters of death, Grindelwald and Dumbledore! Two months of insanity, of cruel dreams, and neglect of the only two members of my family left to me.’ (p.574)

While the above quotations do not overtly suggest addiction, they do imply an overwhelming, constant obsession with unattainable objects, to the point where responsibilities to others is discarded in favour of promoting the obsession. The ‘reality check’ Dumbledore received, which ultimately acted as a traumatic wake-up call, was the death of his sister in a three-way duel between Albus, his brother Aberforth and Grindelwald:

‘Reality returned, in the form of my rough, unlettered, and infinitely more admirable brother. I did not want to hear the truths he shouted at me. I did not want to hear that I could not set forth to seek Hallows with a fragile and unstable sister in tow.

‘The argument became a fight. Grindelwald lost control. That which I had always sensed in him, though I pretended not to, now sprang into terrible being. And Ariana…after all my mother’s care and caution…lay dead upon the floor.’ (p.574)

Throughout much of this commentary I have been quite disparaging towards Dumbledore, focusing intensely on his behaviour from the perspective of viewing it as religious fanaticism or addiction. However, there is one last point I’d like to make as to Dumbledore’s behaviour, something which is supported by textual evidence and underscores the concept of Dumbledore having been addicted to the idea of the Deathly Hallows – a metaphor for absolute power. That point pertains to the following quotation in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in King’s Cross station while Harry is between life and death:

‘I…was offered the post of Minister for Magic, not once, but several times. Naturally I refused, I had learned that I was not to be trusted with power.’ (p.575)

This single statement from Dumbledore – whether he is a figment or Harry’s mind or not – is incredibly important overall for it shows an awareness of one’s character defects and a desire not to fall into them again. This sort of mindset can be seen in cases of ex-alcoholics and other such addicts who desire not to be given the temptation such easy access would provide them; Dumbledore reflects the same reluctance to accept a position of great authority such as that of Minister for Magic even though, prior to this, he greatly desired such power and influence.

In Conclusion

Ultimately, while I can disparage Dumbledore and happily despise him for willingly leaving a child in an abusive home, I cannot, in good faith, ignore the development of his own character and the strength of his own will in overcoming what he perceived as the greatest flaw of his person. I also, cannot disregard the reality that Dumbledore amassed plenty of influential power, through the belief and faith of individuals in magical Britain, but he did not actively utilise much of this influence until it became absolutely necessary.

I still stand by my initial statement that Dumbledore is a decent example of religious fanaticism, of a religious leader who is capable of manipulating others to his view, but I do draw the line on the idea that he does this maliciously; he is meant to act as a mirror to Voldemort in Harry Potter, with Harry himself becoming the ideal.

Dumbledore has been likened to God and to Death in some discussions of his place in the narrative of Harry Potter; I can accept this metaphor when considering his mirrorlike nature to Voldemort – after all, the Devil is a mirror to God with Jesus Christ acting as the ideal. God is capable of great wonder and great horror, much as Dumbledore is capable.

This has been a post of epic proportion, providing textual evidence for much of my original post on which I was questioned. Hopefully it has been educational and somewhat illuminating.

#HP#Harry Potter#Dumbledore#Albus Dumbledore#Wank for ts#Meta#I fucking wrote you a damned essay#Enfuckingjoy

191 notes

·

View notes