#I just love the idea of john as an 80s gay anthems fan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

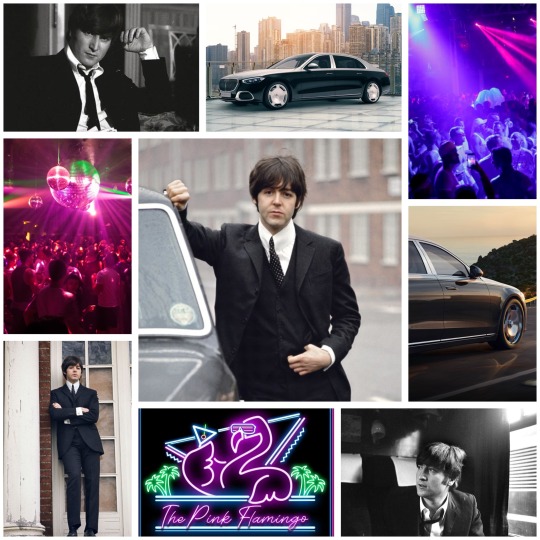

The Life of Riley

Modern AU based on @pie-of-flames's @beatleskinkmeme prompt

John is a terrible driver, but a broke one, so he lets his aunt get him a job as a chauffeur. His first passenger is Paul, the wealthy son of a successful businessman, whose father wants him to follow in his footsteps. It soon becomes clear that neither men are happy with their current situation in life.

Chapter 1 - Haven’t had a dream in a long time

Chapter 2 - The luck I’ve had could make a good man turn bad

Chapter 3 - I find I spend my time waiting on your call

Chapter 4 - Who’s gonna pay attention to your dreams?

Chapter 5 - You take my pride and throw it up against the wall

Chapter 6 - Why pamper life’s complexity when the leather runs smooth on the passenger seat?

Chapter 7 - Who needs a lover that can’t be a friend?

Chapter 8 - Is that the way we stand?

Chapter 9 - Turned over a new leaf and then tore right through it

Chapter 10 - Is my timing that flawed?

Chapter 11 - But to lose you would cut like a knife

Chapter 12 - Heaven knows I'm miserable now

Chapter 13 - Come on baby, we better make a start

#more shenanigans along the lines of double fantasy and brother dearest#insightful literary art it is not#but hopefully people will find it fun#hope you love these boys as much as I do#also I take back what I said about father and son#this might be my favourite playlist#I just love the idea of john as an 80s gay anthems fan#the life of riley#javelin��s playlists#javelin writes#fic:the life of riley#Spotify

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: A Decade of New York City Art and Disco in 10 Tracks

Jack Goldstein, “A Suite of 9 Seven-Inch Records” (1976) (image courtesy 1301PE, Los Angeles)

In July 2012, the artist John Baldessari resigned from the board of Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Then under the direction of Jeffrey Deitch, the museum was planning an exhibition that Baldessari cited as one of the reasons for his departure. “When I heard about that disco show I had to read it twice,” the artist told the Los Angeles Times. “At first I thought ‘this is a joke’ but I realized, no, this is serious.”

His comment was telling, but not surprising. The simple distinction of disco as a ‘joke,’ as opposed to something ‘serious,’ is one that has long held sway in the art world, and like all seemingly simple distinctions, it works hard to suppress its true intentions. It can be traced back at least as far as 1975, when David Mancuso — whose parties in his living space, called The Loft, mark the beginnings of what we now call disco — was moving his invite-only happenings to a new space at 99 Prince Street in Soho. Before Mancuso had even opened his doors, there was a vicious neighborhood campaign, promoted in the pages of the Soho Daily News, to stop his parties from happening. Complaints that the existence of The Loft in Soho would cause a spike in real estate values were articulated, but the campaign’s actual motives were strikingly clear. “This is the beginning of an invasion,” Charles Leslie of the SoHo Artists Association was quoted as saying in the Village Voice.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, disco music — associated with blackness, femininity, and homosexuality — was becoming mainstream via radio hits (The Village People) and successful films (Saturday Night Fever). Quickly, it was deemed threatening. In popular culture, this resentment toward the music, and what it represented, culminated in the ‘Disco Demolition Night,’ a promotional stunt gone awry organized by a local rock station on July 12, 1979, at Comiskey Park in Chicago. The destruction of a crate of disco records — many frisbeed into the pile by irate fans from the stands — between games of a double-header between the Chicago White Sox and Detroit Tigers resulted in a good portion of the crowd storming the field in jubilant rage. ‘Disco Sucks,’ the tagline for the event, became synonymous with reclamation for both mainstream rock and underground punk audiences.

What those two groups had in common, for the most part, was their whiteness. This is rarely mentioned, of course, in relation to the backlash against disco, and that silence has significantly altered not just the history of popular music but also the history of art. At the same time that disco was, according to many, rising and falling in quick succession — a fashion that quickly went out of style — there was a loosely associated group of artists, most of them based around New York City, who we now, for lack of a better term besides postmodern, call the Pictures Generation. In the discussions of the milieu in which their work was created, what is most often referenced is the network of musicians that constituted the no wave scene. This is not a surprise. Disco, or even dancing, rarely factors into the equation.

Tim Lawrence, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980–1983 (courtesy Duke University Press)

This has changed recently. In Tim Lawrence’s Love and Death on the New York Dance Floor (Duke University Press), a historical account of the New York City club scene between the crucial years of 1980 and 1983, two things become readily apparent. The first is that disco, despite popular opinion, never truly died. It changed, as he describes, into a mutant form. It mixed with punk, funk, electro, art rock, and later hip-hop. The true extent of the music that emanated from this period in New York City is more expansive, and interesting, than what can be bundled together under the narrow definition of no wave. The second is that art and disco were decidedly interacting. Artists went to clubs — Keith Haring, Zoe Leonard, and David Wojnarowicz all even worked at Danceateria at one point — played in bands, even stepped behind the turntables. Everybody danced. The boundaries were more fluid, and more acceptable. People traveled between the Mudd Club, where Jean-Michel Basquiat might be spinning John Coltrane records much to the dismay of the dance floor, and the Paradise Garage, where Larry Levan was working up the young, black, and gay crowd into a frenzy, as if there was no difference between the two. They might stop at an opening at the Fun Gallery in between.

Douglas Crimp, Before Pictures (courtesy University of Chicago Press)

The connections between disco, dancing, and the Pictures Generation were further strengthened by Douglas Crimp in his memoir, Before Pictures (Dancing Foxes Press). After discussing an unpublished piece on his experience going to clubs like the Flamingo and 12 West, more diaristic than theoretical, he writes: “What all these places had in common are traits of pariah culture: they were located in out-of-the-way neighborhoods in quickly refurbished spaces with the palpable feeling of being susceptible to a bust at any moment.” Crimp’s use of “pariah culture,” specifically, made me think of the Pictures Generation artists, born of the same era, who utilized those similar fragments — what had been discarded as junk — as material for their work. Each placed an emphasis on the ideas of repurposing and remixing, repetition and movement, and, most importantly, of distance and community. At the same time, Crimp himself, after espousing the pleasures of the dance floor, makes clear his distance from it. “I resisted disinhibition probably because I was trying to get serious about being an art critic right at the time I became a disco bunny,” he writes. Again, that same old separation: seriousness and trivialness, art and disco.

What follows is not intended to be a definitive history of either disco or the Pictures Generation. Using the decade between 1975 and 1985 as a rubric, the idea is to trace the contours of these coexisting groups of artists. Their narratives don’t mirror each other exactly, but by placing the work side-by-side, their shared affinities can be explored and brought to the surface in ways only previously hinted at. Today more than ever, the kinds of marginalized spaces that birthed both disco and the Pictures Generation are under attack. Whether it be the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando or DIY spaces in the wake the tragic fire at Ghost Ship in Oakland, the threats to these communities remain frighteningly real. Hopefully, the result of a new way of looking at the past can be the beginning of new ways of thinking about the present.

1975

Peter Hujar, Hudson River, 1975 David Mancuso’s The Loft (opened in 1970; moved to Soho in 1975)

The photographer Peter Hujar’s images are essential to the structure of Crimp’s Before Pictures in that they present the open spaces of downtown New York as well as capture the sense of community formed around the personalities involved. (Even Zoe Leonard’s pictures , which begin each chapter, bare some kind of resemblance to Hujar’s photographs.) There is a sense in Hujar’s work from the period that everything was connected: terror and joy, straight and gay, loneliness and togetherness. This utopian vision was also built into the ethos at David Mancuso’s aforementioned The Loft. Mancuso, who passed away on November 14, moved his invite-only parties a few blocks down from Broadway to Prince Street in Soho in 1975. Hujar, along with other artists, were frequent visitors. But not all the artists were friends: some, as mentioned earlier, wanted nothing less than the mixed-race gay crowd out of their neighborhood. But Mancuso prevailed, and other clubs opened in the area in the wake of The Loft.

1976

Jack Goldstein, “A Suite of Nine 7-Inch Records with Sound Effects,” 1976 Double Exposure, “Ten Percent” (Walter Gibbons Remix)

Walter Gibbons is said to have discovered the effect of extending the “break” in funk and soul records at the same as DJ Kool Herc in the Bronx. But his legacy is much less cemented due to his alliance with disco, despite his massive contributions to the art of DJ-ing and dance music more generally. His mix of Double Exposure’s “Ten Percent” was the first commercially released 12-inch single, changing the way music was manipulated and presented. Like the artist Jack Goldstein, Gibbons went through a period of total obscurity, and only recently has received recognition. Goldstein’s “A Suite of Nine 7-Inch Records with Sound Effects,” consists of a series of 7-inch singles, created by the artist and pressed in different colors, which contain sound effects he created as the start points for film ideas. Goldstein, much like Gibbons, presents vinyl as material, a household object turned into a creative tool.

1977

Cindy Sherman, “Untitled Film Still #6” (1977), gelatin silver print, 9 7/16 x 6 1/2 in, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, acquired through the generosity of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder in memory of Eugene M. Schwartz (© Cindy Sherman)

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills, 1977–80 Donna Summer, “I Feel Love”

There is a haunted quality to both “I Feel Love” and the Untitled Film Stills that is a result of the tension between the old and the new. Donna Summer’s bionic-disco anthem, produced by Giorgio Moroder, sends the vocalist gliding through a stripped-down web of rhythmic, synthesized pulses. It was as genre-defining as Cindy Sherman’s photographs, produced between 1977 and 1980, which recast the artist as a series of B-movie clichés. Both works explore terror and pleasure through a combination of repetition and artifice to scramble codes of femininity.

1978

Faith Ringgold, Harlem ’78 series, 1978 TV Party

Faith Ringgold’s Harlem ’78 series of soft sculptures are not the artist’s most well known work. But the life-sized dolls that formed the installation were part of Ringgold’s attempt to “capture the spirit of Harlem,” as she writes in her memoir, a community of recognizable objects that resembled the “familiar faces I pass on the street.” The backdrop to the installation was a large canvas that viewers were encouraged to write on, like a graffiti mural. A similar sense of community building was happening downtown that same year with TV Party, the public access television show created by Interview Magazine editor Glenn O’Brien and Blondie guitarist Chris Stein. “It was a declaration that we were here and were about to lay down what culture in New York City was going to be at the time,” Fab Five Freddy, a regular guest of the show, is quoted as saying in Lawrence’s book. “Downtown was just an energy at that moment. There was this sense of commonality and reciprocity, this idea that different things could happen and were possible.”

1979

Installation view of Robert Longo’s “Men in the Cities – Men Trapped in Ice” at the Rubell Family Collection (photo by Hrag Vartanian for Hyperallergic)

Robert Longo, Men in the Cities, 1979 Blondie, “Heart of Glass”

Are the figures in Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities drawing having seizures, or are they dancing? In his large, black-and-white images of suited men, there is a celebration, it seems, of the nervous energy of movement, bound and wound with tension and ready for release. But they are undercut by the technical perfection of the drawings, much like Blondie’s “Heart of Glass,” a song that came out the same year. Coming out of the punk scene that formed around CBGB, Blondie was one of the first groups (even before the Talking Heads) to embrace dance floor rhythms, including disco and later hip-hop. “Heart of Glass” used its slickness to frame its fragility — the shattering love of the lyrics — and opened up a new direction for musicians to travel following punk’s decline.

1980

Downtown ’81 Loose Joints, “Is It All Over My Face?”

Further embrace of the mainstream, with a bump and a twirl: Downtown ’81 (originally titled New York Beat) stars Jean-Michel Basquiat as himself, wandering around the ruins of downtown Manhattan attempting to sell a painting after getting evicted. On his journey he encounters artists, musicians, and other assorted street folk, all connected by the maze of blocks they call home. The film was meant to be a translation of downtown energy for the masses, but wasn’t released for over 20 years due to a scandal involving its Italian backer, who pulled out of the project before it was finished. (Wild Style, a hip-hop focused narrative film that came out three years later, would achieve what Downtown ’81 could not.) At the same time, Arthur Russell, an avant-garde musician and former music director at the Kitchen, was becoming more invested in making records for the dance floor. After discovering the pleasures of disco at the Gallery, he began making records under a variety of aliases and with different collaborators. Loose Joints, a joint effort with Steve D’Acquisto, produced what is arguably one of his greatest songs, “Is It All Over My Face?” The song got major play at the Paradise Garage, via a remix by the club’s resident DJ, Larry Levan, and would later be in regular rotation on New York City’s WBLS. The song echoed Russell’s feeling “that dance music needed to abandon its slick, streamlined incarnation in order to reconnect with the floor,” Lawrence writes, “and exemplified the ‘anything goes’ philosophy of the post–disco sucks era.”

1981

Barbara Kruger, “Untitled (Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face)” (1981), gelatin silver print, 66 x 48 in (courtesy Sprüth Magers)

Barbara Kruger, “Untitled (Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face),” 1981 Grandmaster Flash & the Furious 5, “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel”

The brash photomontages of Barbara Kruger have become, for better of worse, one of the defining stylistic remnants of the Pictures Generation, and find their mirror in “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel.” Produced entirely of other people’s records, the song popularized the scratching and beat juggling that was already happening in park jams in the Bronx (not to mention in disco clubs), and highlighted the combination of sounds that formed early hip-hop. Its defiant mashup of different styles was as bold, aggressive, and playful in its communication as Kruger’s cut-ups.

1982

Untitled Keith Haring subway drawings from 1982 at Tony Shafrazi Gallery in 2010 (photo by Hrag Vartanian for Hyperallergic)

Keith Haring, Subway Drawings, 1982–83 Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force, “Planet Rock”

“The studio and the subway started growing together, and the subway became like a drawing workshop to develop ideas and for the vocabulary to expand,” Keith Haring wrote of his Subway Drawings, which he began producing more regularly around 1982. The simple figures that adorned poster advertisements in train stations across the city — Haring would draw them quickly, then call his friend Tseng Kwong Chi so he could follow and photograph them — were timed, as Lawrence notes, to the exact period when then New York City Mayor Ed Koch began dispatching dogs to subway yards to curb vandalism. The Subway Drawings also marked a greater emphasis in Haring’s work on the rhythms of the street. Jeffrey Deitch, in an early essay about Haring’s work, noted that the artist “liked to work to the accompaniment of a boom box, to the point where it seemed as though he worked like he was a dancer, with his work a visualization of the music.” Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock,” released the same year, fused the burgeoning sounds of hip-hop rhyming with an elevated form of synthetic funk. The song, writes Lawrence, “shredded the categories that had defined the 1970s — disco, dub reggae, rock, punk, and new wave — and in so doing revealed how, for all their radicalness, they had fallen short of capturing the complexity of New York.” Haring and Bambaataa frequently crossed paths, and the latter’s explorations of space in his music undoubtedly influenced the UFO imagery that became a centerpiece to the moving bodies of the Subway Drawings.

1983

Adrian Piper, “Funk Lessons,” 1983 K-Rob vs. Rammellzee, “Beat Bop”

Rammellzee had already exhibited work at the historic New York/New Wave show at PS1 in 1981, when he made a record with his friend K-Rob and Jean-Michel Basquiat called “Beat Bop.” Produced by Basquiat and featuring his artwork on the cover, the song ushered in a “space-conscious, experimental, often surreal aesthetic into a new downtown-meets-the-Bronx amalgam,” Lawrence writes, with the song’s streetwise lyrics, penned by the two rappers (after they rejected what Basquait had written for them), bumping up against the effect-heavy instrumentation. Like “Beat Bop,” there is a confrontation embedded in the fabric of Adrian Piper’s performance “Funk Lessons,” produced for the first time that same year. One of the few works of the period to directly address disco music and dance, Piper’s filmed “lessons” deconstruct the racial discrimination inherent in the public perception of the dance floor and highlight the mutations Lawrence keenly explores in his book.

1984

vimeo

Dan Graham, “Rock My Religion” (1983–84) Run-DMC, “Rock Box”

One of the first combinations of rap and rock on record, “Rock Box” by Run-DMC also began to signal hip-hop’s move away from its dance music roots. The song put a greater emphasis on simplicity, with a harder edge and a focus on guitars. This was music meant for the boom box, the car radio, to be played out in the street. Dan Graham’s video “Rock My Religion,” finished in 1984, doesn’t explicitly focus on disco or hip-hop, but in its slice-and-dice construction and multiplicity of influences — shaker dances, post-punk guitar noise, the jittery ramblings of Patti Smith — mirrors contemporary music’s embrace of contradictory forms.

1985

Nan Goldin, “The Parents’ Wedding Photo, Swampscott, Massachusetts” (1985), from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, silver dye bleach print, printed 2006, 15 1/2 x 23 1/8 in, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, acquired through the generosity of Richard O. Rieger (© 2016 Nan Goldin)

Nan Goldin, The Battle of Sexual Dependency Phuture, “Acid Tracks”

“Acid Tracks,” produced in Chicago by DJ Pierre, Earl “Spanky” Smith, and Herbert Jackson (collaborating under the name Phuture), sounds like “[t]welve minutes of a machine eating its own wires,” writes Michaelangelo Matos in his book, The Underground Is Massive, and represents the next mutation of disco music following hip-hop’s sideways departure. Disco had been spawning different forms all over the country, including Chicago House and Detroit Techno, and “Acid Tracks” helped define what was called Acid House, which spread to even more popularity in the UK and whose influence can be felt in all forms of electronic (and even pop) music that followed. Here were sounds, once again, meant for the club, and movement, and the joining of collective energies. Nan Goldin’s The Battle of Sexual Dependency, has been just as important a founding document. The slideshow, set to music and featuring startlingly personal images, represented an extension of the Pictures Generation’s interest in the material object. Goldin’s candid photos are presented by way of the family ritual of the slide projector, but are meticulously shaped into splintering narratives accompanied by a jukebox assortment of songs. The images look inward but were presented, in their earliest stages, at clubs and in performance spaces. Goldin’s reframing of the quotidian as something more meaningful, her celebration of collective gathering and its expression of catharsis, has its antecedent in disco.

The post A Decade of New York City Art and Disco in 10 Tracks appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2jEcV8X via IFTTT

0 notes