#I have to hand in an assignment about an archeological site of my choice

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Just signed up for an online course on Ancient Greek and Roman archeology!

#aahh#I have to hand in an assignment about an archeological site of my choice#@the temple of Artemis Brauronia: there I go!!#the course is organized by Udima (Spain)#personal

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences - Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star

This has been an important book for my project, returning me to the topic of classification. The book explores the role of categories and standards in shaping the modern world. It investigates a variety of classification systems, including the classification of diseases, the Nursing Interventions Classification, race classification under apartheid in South Africa, and the classification of viruses. The book touches on points covered in my dissertation such as information black-boxes, and the issues raised by Haraway around objectivity. The book also takes a similar archeological approach to my dissertation. It’s quite surprising and depressing that this book was written in 1999. It feels like very little has progressed in terms of people’s wariness of classification - which is especially concerning in light of ongoing AI developments.

I began transcribing important moments in the book...the list got rather long!

Remarkably for such a central part of our lives, we stand for the most part in formal ignorance of the social and moral order created by these invisible, potent entities. p.3

Information scientists work every day on the design, delegation, and choice of classification systems and standards, yet few see them as artefacts embodying moral and aesthetic choices that in turn craft people’s identities, aspirations, and dignity. p.4

Foucault’s (1970; 1982) work comes the closest to a thoroughgoing examination in his arguments that an archaeological dig is necessary to find the origins and consequences of a range of social categories and practices. p.5

No one, including Foucault, has systematically tackled the question of how these properties inform social and moral order via the new technological and electronic infrastructures. Few have looked at the creation and maintenance of complex classifications as a kind of work practice, with its attendant financial, skill and moral dimensions. p.5

Every link in hypertext creates a category. That is, it reflects some judgment about two ore more objects: they are the same, or alike, or functionally linked, or linked as part of an unfolding series. p.7

In this, a cross-disciplinary approach is critical. Any information systems design that neglects use and user semantics is bound for trouble down the line - it will become either oppressive or irrelevant. p.7

- Who does what work? We explore the fact that all this magic involves much work: there is a lot of hard labor in effortless ease. Such invisible work is often not only underpaid, it is severely underrepresented in theoretical literature (Star and Strauss 1999). We will discuss where all the “missing work” that makes things look magical goes. p.9

Classification: A classification is a spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal segmentation of the world. A “classification system” is a set of boxes (metaphorical or literal) into which things can be put to then do some kind of work - bureaucratic or knowledge production p.10

The system is not complete. With respect to the items, actions, or areas under its consideration, the ideal classification system provides total coverage of the world it describes. So, for example, a botanical classifier would not simply ignore a newly discovered plant, but would always strive to name it. A physician using a diagnostic classification must enter something into the patient’s record where a category is called for; where unknown, the possibility exists of a medical discovery, to be absorbed into the complete system of classifying. No real-world working classification system that we have looked at meets these “simple” requirements and we doubt that any ever could. p.11

It is a struggle to step back from this complexity and think about the issue of ubiquity rather than try to trace the myriad connections in any one case. The ubiquity of classifications and standards is curiously difficult to see, as we are quite schooled in ignoring both, for a variety of interesting reasons. We also need concepts for understanding movements, textures, and shifts that will grasp patterns within the ubiquitous larger phenomenon. The distribution of residual categories (“not elsewhere classified” or “other”) is one such concept. “Others” are everywhere, structuring social order. pp.38-39

An Aristotelian classification works according to a set of binary characteristics that the object being classified either presents or does not present. At each level of classification, enough binary features are adduced to place any member of a given population into one and only one class. p.62

Goodwin (1996) provides an elegant description of working student archaeologists matching patches of earth against a standard set of colour patches in the Munsell colour charts. He argues that earlier cognitive anthropological work on colour assumed a universal genetic origin for colour recognition, but failed to examine the kinds of practices that informed the ways in which colour tests were designed and carried out in the course of this research. p.65

The classification system that is the ICD does more than provide a series of boxes into which diseases can be put; it also encapsulates a series of stories that are the preferred narratives of the ICD’s designers. pp.77-78

One of this book’s central arguments is that classification systems are often sites of political and social struggles, but that these sites are difficult to approach. Politically and socially charged agendas are often first presented as purely technical and they are difficult even to see. As layers of classification system become enfolded into a working infrastructure, the original political intervention becomes more and more firmly entrenched. p.196

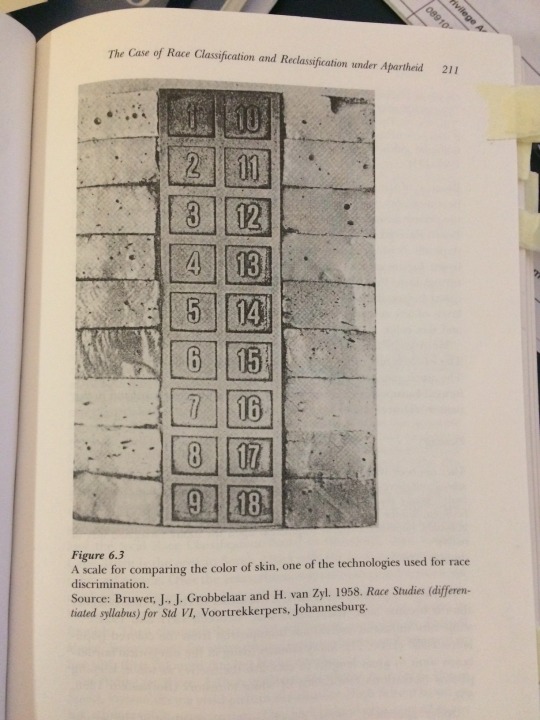

“If you’re black and pretend you’re Coloured, the police has the pencil test.” “The pencil test?” “Oh, yes, sir. They sticks a pencil in your hair and you has to bend down, and if your hair holds the pencil, that shows it’s too woolly, too thick. You can’t be Coloured with woolly hair like that. You go to stay black, you see.” (Sowden 1968, 184) p.212

In the early pre-apartheid days, it was easier to change race category than it became later. Kahn notes that “between 1911 and 1921… some fifty thousand individuals disappeared from the coloured population rolls” (1966, 51). Many families living in the categorical borderlands went to great length to establish themselves as white, keeping photos (sometimes fabricated) of white ancestors (Boronstein 1988, 55).

Language and Race as Conflicting Categories: There are thousands of ironic and tragic cases where classification and reclassification separated families, disrupted biographies, and damaged individuals beyond repair. The rigid boxes of race disregarded, among other things, important linguistic differences, especially among African tribal languages. p.218

The Case of Sandra Laing - “Ten-year-old Sandra Laing slipped unnoticed into the school cloakroom. She made sure she was alone, then picked up a can of white scouring powder and hastily sprinkled her face, arms and hands. Remembering the teasing she had just endured in the schoolyard during recess, she began scrubbing vigorously, trying to wash off the natural brown colour of her skin.” (Ebony 1968, 85)m - p.221

Invisible Categories - an anecdote related to literary critic Alice Deck: In the 1930s, an African-American woman travels to South Africa. In the Captetown airport, she looks around for a toilet. She finds four, labeled: “White Women”, “Colored Women,” “White Men,” and “Colored Men.” (Colored in this context means Asian.) She is uncertain what to do; there are no toilets for “Black Women” or “Black Men,” since black Africans under the apartheid regime are not expected to travel, and she is among the first African Americans to visit South Africa. She is forced to make a decision that will cause her embarrassment or even police harassment. p.245

Three social institutions, more than any others, claim perfect memory: the institutions of science, the law, and religion. p.275

Scientific professionals, thought, have often claimed that by its very nature science displays perfect memory. p. 275

Information, in Bateson’s famous definition, is about differences that make a difference. Designers of classification schemes constantly have to decide what really makes a difference; along the way they develop an economy of knowledge that articulates clearance and erasure and ensure that all and only relevant features of the object (a disease, a body, a nursing intervention) being classified are remembered. In this case, the classification system can be incorporated into an information infrastructure that is delegated the role of paying due attention. A corollary of the “if it moves, count it” theory is the proposition “if you can’t see it moving, forget it.” The nurses we looked at tried to guarantee that they would not be forgotten (wiped from the record) by insisting that the information infrastructure pay due attention to their activities. p. 281

This final part of the book attempts to weave the threads from each of the chapters into a broader theoretical fabric. Thought the book we have demonstrated that categories are tied to the things that people do; to the worlds to which they belong. In large-scale systems those worlds often come into conflict. The conflicts are resolved in a variety of ways. Sometimes boundary objects are created that allow for cooperation across borders. At other times, such as in the case of apartheid, voices are stifled and violence obtains. p.283

Assigning things, people, or their actions to categories is a ubiquitous part of work in the modern, bureaucratic state. Categories in this sense arise from work and from other kinds of organised activity, including the conflicts over meaning that occur when multiple groups fight over the nature of a classification system and its categories. p.285

One of the interesting features of communication is that, broadly speaking, to be perceived, information must reside in more than one context. We know what something is by contrast with what it is not. Silence makes musical notes perceivable; conversation is understood as a contrast of contexts, speaker and hearer, wonders, breaks and breaths. In turn, in order to be meaningful, these contexts of information must be relinked through some sort of judgement of equivalence or comparability. This occurs at all levels of scale, and we all do it routinely as part of everyday life. pp.290-291

Consider, for example, the design of a computer system to support collaborative writing. Eevi Beck (1995, 53) studied the evolution of one such system where “how two authors, who were in different places, wrote an academic publication together making use of computers. The work they were doing and the way in which they did it was inseparable from their immediate environment and the culture which it was part of.” To make the whole system work, they had to juggle time zones, spouses’ schedules, and sensitivities about parts of work practice such as finishing each other’s sentences as well as manipulating the technical aspects of writing software and hardware. p.291

The marginal person, who is for example of mixed race, is portrayed as the troubled outsider; just as the thing that does not fit into one bin or another gets put into a “residual” category. p.300

The myriad of classifications and standards that surround and support the modern world, however, often blind people to the importance of the “other” category as constitutive of the whole social architecture (Derrida 1980).

Such “marginal” people have long been of interest to social scientists and novelists alike. Marginality as a technical term in sociology refers to human membership in more than one community of practice. p.302

Marginality is an interesting paradoxical concept for people and things. On the one hand, membership means the naturalisation of objects that mediate action. On the other, everyone is a member of multiple communities of practice. p.302

“I am an East Ender therefore I must talk like this; and I must drink such and such a brand of beer.” Aided by bureaucratic institutions, such cultural features take on a real social weight. If official documents force an Anglo-Australian to choose one identity or the other - and if friends and colleagues encourage that person, for the convenience of small talk, to make a choice - then they are likely to become ever more Australian, suffering alongside his or her now fellow country people if new immigration measures are introduced in America or if “we” lose a cricket test. The same process occurs with objects - once a film has been thrown into the x-rated bin, then there is a strong incentive for the director to make it really x-rated; once a house has been posted as condemned, then people will feel free to trash it. p.311

“Similarity is an institution” Mary Douglas (1986, 55) p.312

In this book we demonstrate that classifications should be recognised as the significant site of political and ethical work that they are. p.319

In the past 100 years, people in all lines of work have jointly constructed and incredible, interlocking set of categories, standards, and means for interoperating infrastructural technologies. We hardly know what we have built. p.319

The moral questions arise when the categories of the powerful become the taken for granted; when policy decisions are layered into inaccessible technological structures; when one group’s visibility comes at the expense of another’s suffering. p.320

The importance lies in a fundamental rethinking of the nature of information systems. We need to recognise political values, modulated by local administrative procedures. These systems are active creators of categories in the world as well as simulators of existing categories. p.321

Often using innovative techniques such as imaginary devices, but not traditional formulaic means, they achieved the right answer the wrong way. One child called this “the dirt way.” p.321

We have suggested one design aid here - long-term and detailed ethnographic and historical studies of information systems in use - so that we can build up an analytic vocabulary appropriate to the task. p.323

- Rendering voice retrievable. As classification systems get ever more deeply embedded into working infrastructures, they risk getting black boxed and thence made both potent and invisible. By keeping the voice of classifiers and their constituents present, the system can retain maximum political flexibility. This includes the key ability to be able to change with changing natural, organisational, and political imperatives. p.325

This integration began roughly in the 1850s, coming to maturity in the late nineteenth century with the flourishing of systems of standardisation for international trade and epidemiology. p.326

On a pessimistic view, we are taking a series of increasingly irreversible steps toward a given set of highly limited and problematic descriptions of what the world is and how we are in the world. p.326

We have argued that a key for the future is to produce flexible classifications whose users are aware of their political and organisational dimensions and which explicitly retain traces of their construction. In the best of all possible worlds, at any given moment, the past could be reordered to better reflect multiple constituencies now and then. p.326

In this same optimal world, we could tune our classifications to reflect new institutional arrangements or personal trajectories - reconfigure the world on the fly. The only good classification is a living classification. p.326

1 note

·

View note