#I feel homophobes will either go with my birth name or chosen name to try to misgender me only to realize the bar is on the floor lol

Text

Heyo I'm Sonic/Matilda (he/dgeh/og jokers get blocked)

It's currently 4 am as of writing this so I'm more exhausted than usual (didn't know that could happen)

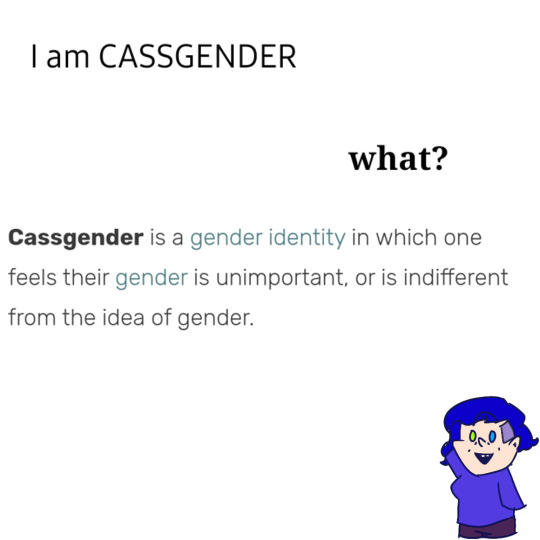

I wanted to make a little post about gender (sort of)

I do not enjoy explaining things at all so this is short and rushed

#tag 💤#fun fact this was gonna be a gender wheel joke but I thought 'hey I could do something with this' then did and wanted to go back right away#couldn't tho. don't care.#I'm something of human#cassgender#I feel homophobes will either go with my birth name or chosen name to try to misgender me only to realize the bar is on the floor lol#I physically cannot care less#also so random but you may (or may not) have noticed I have heterochromia#random but true#also I don't draw chibi much (at all. ever.) so it looks odd#artist tag 💤

0 notes

Text

No, I am not being a troll

As my url states, I have autogynephilia and by common definition I am transfem/TIM, but I also support radical feminism generally and its stance on trans people specifically (I know that a lot of you consider "TERF" a slur, but I picked it as more open, because a lot of people here are trying to make radical feminism trans-inclusive by removing sex-based oppression from it).

Why do I believe in sex-based oppression?

Because it obviously exists and you can see it in how transmasculine people are treated

Because it's the only meaningful explanation of emergence of patriarchy

Because sex of trans people still affects our lives and everyone recognizes it

I went through a brief period of detransition because of severe doubts, and it made me realize that attempts at describing patriarchy as "gender-based oppression" fail to address cases of detransitioners

My stance on trans people

(This has gotten long, but TL/DR: sex and gender are different, and both are valid in different contexts)

I don't think that trans people are purposefully being predatory and inherently wicked, don't come at me with this thing.

I don't think that gender identity is innate the way sexuality is, I do believe that it's constructed, but I don't think that it's not real altogether. It's real the same way ethnicity or religion are - there is nothing in your brain that makes you Swede or Catholic, but this identity has meaning to people and affects their lives. And I don't mean masculinity/femininity by it, I have masculine female friends who I am not trying to trans, and GNC trans people are real.

Some people are trans because of life-long physical dysphoria, some because they detest social expectations, some internalize homophobic or sexist stereotypes, some do it because of AGP/AHE (which is not some dirty perversion), some have culturally-specific reasons, and much more. Obviously, different groups of trans people have different needs, and some of them wouldn't be trans in different societies or won't be in the futue, but they are trans now and that's something you can't dismiss.

However, one's gender identity doesn't erase your sex (though a lot of trans people tend to emphasize with people of their gender rather than sex), and doesn't make you entitled to be included in someone's sexuality. Sexuality is about body as much as it's about personality, and it's bodies that we have innate attraction to. Existence of trans people and especially medically transitioning ones does complicate categorization, because some people may be only attracted to men in daily lives but also wouldn't mind transmasc partner who is on T but didn't have SRS, some would dislike even fully operated partner because other features or even because of their AGAB (and it's fine), and some people may have no preference in bodies but strong preference in gender identity, and so on. But in the end of the day, for a lot of people it's either birth sex that matters or they are bisexual, and it's completely fine.

This attitude is especially gross when it comes to gay people, because on top of trans people simply not being attractive to them it provokes their trauma response.

Why do I call myself AGP?

This is complicated and some of it is just for edginess.

But also I recognize that my physical dysphoria is pretty insignificant and incomplete, and I can't even prove that it won't go away. That's why I decided to not transition.

When I say AGP I mean that I feel a thrill when I think of myself as a girl etc. I don't get hard from it and don't enjoy being degraded for femininity, as transphobic caricatures say, but I think that foundation of my AGP is at least partially in attraction to women.

It also highlights the fact that I am probably not a "true transsexual" or otherwise absolutely inborn woman, and I accept it. Whatever.

Some additional information:

My chosen name is Belle

This blog exists as my attempt to build bridges from transfem side (transmascs both do it themselves and some cis women reach out to them) and to provide insights both about lives of transfems and views of radical feminists to anyone who asks

I am into women, but I don't call myself a lesbian because it feels like too much of an intrusion. I won't describe my sexuality further here, but asks are open

DNI: misogynists, homophobes, racists (including antisemites and zionists)

If you feel uncomfortable about me - just block me, I won't feel bad

I admit being male, but I still dislike it. It's always fine to point how being socialized as a boy or being perceived as male changes my social life, and I recognize sexual dimorphism in reasonable (i.e. real) terms, but I would like you to not go out of your way to trigger my dysphoria. Thank you

#transgender#transfem#trans woman#radblr#radical feminists do interact#gender critical#radio belle#autogynephilia

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Additional Thoughts About My Birth Name, and Why It Was So Dysphoric

I’ve always hated my birth name. Always, always, always. (I wholeheartedly apologise in advance for anyone with the same name; I’m sure it’s a great name for you! I just didn’t like it for myself.)

The one and only reason I stuck with it and put up with it for so long was because I didn’t know what to change it to. It took me a long time to come up with “Ievan” and find that one elusive name I was totally comfortable with. But I wanted to try and delve into the reasons why I hated it so much; why it elicited that level of deep discomfort and dysphoria within me.

For those who don’t know, my birth name is “Stacey”. Not “Stacie”, as many people who know me may be more familiar with. Changing the spelling was something I did later on, to try and exert some sense of control over it. But I’ll come back to that.

As far back as I can remember, hearing or seeing my name provoked a generic, non-specific sense of dread and discomfort deep within me. For the most part, I didn’t really know why; it just did. I just didn’t like it. My loathing of my own name was a puzzle I wasn’t able to solve; but now, I have a few more of the pieces.

I think the first time I can remember feeling that discomfort came in the form of discovering that “Stacey” (or any variations/ derivatives thereof) could be a “boy’s name”, as well. I didn’t personally know any boy or man called “Stacey”; but I knew of men called Stacey, through friends of friends of family. When I, as a young child (this would have been primary school age, I think), first heard that Stacey could be a boy’s name too, I was mortified.

I was mortified to be associated with boys in the same sort of way that some of the worst homophobes are closeted homosexuals themselves; or that some of the worst sexists against women are women themselves. (I, too, was guilty of the latter.) I was mortified because I was insecure. I took the fact that “Stacey” could be a man’s name as an attack on my own femininity — a thing that was already under threat.

It’s not that I thought boys were inherently bad. It’s that I thought that being a girl who was like a boy was bad. Being like a boy, when you were not a boy, was bad; because as a girl, I had to be a girl. I had no problems with other boys being boys, or other girls being girls. My problem was with me, and not knowing where I fit in.

I was a “girl”, and thus, I was expected to be a “girl”; and as such, I already felt a lot of pressure to be “like a girl” and be “girly”. I was already struggling with trying to live up to expectations for my assigned gender, and already felt bad that my own behaviour was more boyish; like I wasn’t good enough the way I was, and was failing in some way, because “being a girl” wasn’t something I excelled at. Having a boyish name (even if it’s not actually that boyish; just unisex) felt a lot like yet another nail in the proverbial coffin: it was another thing I had to struggle against to try and prove that I was “feminine enough”; that I was good enough, the way I was. I saw it as another thing counting against me.

I couldn’t put those feelings into words, of course; it was not something I could identify or understand. There was just that unconscious association that being a “girl who was like a boy” was bad — that I should either be “a boy” or “a girl”, except that I couldn’t possibly be “a boy” because I wasn’t born male, and therefore I was stuck with being “a girl” instead.

My name being associated with masculinity in any way seemed to fly in the face of my already-laboured pursuit of the feminine. So that was one reason I hated it.

And it’s weird, because none of the beliefs I just referenced about what it means to be a boy/ a girl were actually mine. I had just internalised them. I don’t even know for sure that they belonged to any one person I knew in particular. But that is what I thought other people thought I should be like, and I censored myself accordingly. I didn’t have anyone to tell me that I was okay, the way I was.

Getting into it more specifically, there were lots of little things I didn’t like about my name. I didn’t like the way it looked. I didn’t like the way it sounded. I didn’t like the letter “y”. (Again, my apologies to anyone who has a “y” in their name!)

I didn’t like the fact that my name didn’t hold any specific meaning or emotional significance to my parents when they picked it for me. My parents simply couldn’t decide what to call me; they couldn’t settle on one single name they loved. So they both wrote a list of several names they liked well enough, and cross-referenced their lists for names that appeared on both. I guess that does still count as a story behind the name; just not one rooted in sentiment. It’s almost as if my parents knew; as if they experienced some portent or some foresight that I would be difficult to define, and that doing so was beyond their capability. And how could I fault them for that? Before I came to terms with my identity and realised I was non-binary, it had been beyond my capability as well. I had been looking at it the wrong way — not only the wrong way, but focusing on the wrong thing. But I digress.

I didn’t like the way there were so many different names which all sounded similar to Stacey. I didn’t like the way that no-one ever knew how to spell it, and people always spelled it wrong. (Contrast this to “Ievan”, where the freedom and flexibility in playing around with the spelling and the derivatives thereof is something I enjoy.) And that’s because, being a socially anxious child, I didn’t like how I had to have repeat conversations with adults about my name; especially when conversation was something that I hated, and my name was something that I hated, too. (Whereas now, I like my new name, and thus, like talking about it.)

It was humiliating and embarrassing that adults insisted on engaging with me, and yet repeatedly failed to understand me. It was frustrating, and demoralising, too.

I remember this conversation with one of the supervisors at playscheme, when I was signing in for the day:

Adult: Hi! What’s your name?

Awkward and shy child me, in a whisper: Stacey.

Adult: What’s that? Tracy?

Awkward and shy child me, trying to raise my voice and feeling very uncomfortable: No, Stacey.

Adult: I’m sorry? I still didn’t catch that. Did you say Daisy?

Awkward and shy child me, on the verge of tears: No, Stacey!

Adult: Oh, Stacey! Well, why didn’t you say so? *Proceeds to write it down incorrectly.*

Awkward and shy child me: But that’s not — That’s not how you —oh, nevermind… *trails off miserably*

That was one specific exchange, but I have had to have many similar ones; all variations upon the theme of, “Let’s all talk about the name ‘Stacey’ for five minutes, despite the fact I hate the name ‘Stacey’ and would rather not be talking about it at all.”

Eventually, something happened to at least shift some of the discomfort I felt with my name. In 2003, singer and songwriter Stacie Orrico released a song called More to Life. I was 12 at the time, and in my second year of high school. I was obsessed with this song. It spoke to me on so many levels, capturing the melancholy and despair that I was feeling at that time; resonating with me with the idea that surely, there has to be more to it than this. If there isn’t, then what’s the point? Looking back at the lyrics now as an adult, it seems to be about drugs and a battle with addiction, depending on substance abuse as a means of distraction from an otherwise-empty life. That is not how I interpreted at the time, though: I interpreted it as being about how life was empty and devoid of meaning; about the endless questioning about why life was the way it was and trying to make sense of it; trying to make it better.

It was also the first time I had seen a celebrity with the same name as me. It was the first time I had heard of anyone except family-friend-Stacey-who-was-a-boy who had the same name as me. Immediately, I wanted to change the way I spelled my name from “Stacey” to “Stacie”, to be more like Stacie Orrico. And doing that helped; a bit. I got rid of the “y” I didn’t like, and the “ie” combination looked far more visibly appealing to me. (That “ie” combination is found in “Ievan”, too! That is the one tie between my old name and my new name, and adds another level of significance to the name “Ievan” and why I like it.) I felt like I got some control back over my own name, by at least choosing how it was spelled.

But it didn’t alleviate much. After all, how my name sounded was no different. It remained a name I had not chosen for myself, but one my parents had picked for me and thrust upon me. Additionally, changing my spelling presented a new problem. I knew how I wanted to spell it: but when and where and how could I actually do so?

At school, even if I said I preferred to spell it as “Stacie”, all my records and legal paperwork would still read “Stacey”. I became incredibly anxious about the potential confusion it might cause; that it would just lead to more conversations about my name, or about the correct spelling of my name, if I turned in a piece of work to my teachers with the name “Stacie” when the official record said otherwise.

I honestly don’t remember how I first broached the subject with my high school teachers. I do remember that I did end up having to have a lot of conversations, about how “it’s spelled ‘Stacey’ on my passport, but I prefer to spell it ‘Stacie’.” But eventually, everyone in my high school got used to it. There had been a discrepancy at first; but by the end, they knew that “Stacie” was me, and I was “Stacie”. That was fine. That worked great. However…

When I left high school and started university, I had to go through the whole process again. I was moving to a different country; I was registering as a citizen in another land; and I needed to send across photocopies of my birth certificate and my passport. Even on a day-to-day basis, using my passport as my ID was frequently necessary. So when I was signing up as a student and getting my student ID, I felt compelled to revert back to the name “Stacey”, so that it was spelled the same way as it was on all my legal documents.

Unlike high school — where all my teachers knew me personally and got used to me and my preferred spelling — university was highly impersonal. There was little to no interaction actually with the teachers. I sat in a lecture hall of 300 people, taking notes. All our coursework was online. Everything was processed digitally. I didn’t think the system would take very kindly to the idea of me spelling my name in a way that was different from all of my identification, both online and in paper.

So, reluctantly, I went back to spelling my name “the legal way”; not just in university, but in my day-to-day life, as well. I got so used to spelling it that way whenever it came to do with university or immigration, it spilled over to other aspects of life as well. I changed my Facebook page, which I created under “Stacie”, to read “Stacey” instead. Otherwise, the friends I met at university might have been confused and not recognise me when I added them online.

I never actually had a conversation with anyone else about what I should do about spelling my name a different way. I never actually had a conversation with my university or with legal authorities about what approach I should take, or if there was a way to operate under a “preferred name” instead of my legal name. Again, I was censoring myself. I was the one who assumed it would be a problem or cause issues. It was due to my own anxiety and my own internalised pressure to conform — to not inconvenience anyone else — that I tried to just blend in, be “normal”, and get by with as little fuss as possible.

Luckily, reverting to “Stacey” didn’t last very long. As soon as I was out of university, I switched back to “Stacie” and continued using it once more. I still didn’t like “Stacie”; but I liked it more than “Stacey”. In that one small way, I did want to stand up for myself, now there was no longer the need to use “Stacey” on a daily basis in the form of signing in to university. (And yes; a lot of confusion was caused along the way.)

At around this time, one of my friends from high school announced that she wanted to change her name. For privacy reasons, I won’t name her. But she, as a person, is an incredibly girly-girl kind of girl. She loves make-up and fashion and cute, frilly clothes and she is obsessed with pink. (Seriously, you should see her bedroom! It’s wall-to-wall awash in pink and very many pink and cutesy things!) She is a girly girl, and loves it. And that’s okay! I say this not to pass judgment; we are very different people, and while the whole girly-girl aesthetic isn’t for me, it suits her very well. Rather, I tell you this for context.

See, this incredibly girly girl had a “boy’s name”. Not in the same way that “Stacey” could be a boy’s name, but wasn’t often used as one; no, her birth name was ubiquitously “boy”.

I, as an outsider, thought that was so cool. I thought it was so cool, to be a girl with a boy’s name. I absolutely loved the idea. (Yes, this does seem contradictory to what I said before, about viewing having a name that could be in any way associated with a boy as an attack on my own femininity — but remember that I only felt that way due to being insecure in my own femininity to begin with. And also remember that I tend not to apply the same tolerance, love and acceptance to myself as I do to others. Hence why, as a child, I didn’t like that my name smeared me as “less than” in regards to being “a girl”; but as a more mature adult, I actively envied the possibility of having what was more typically a boy’s name.)

But my friend herself didn’t like her own name. She wanted to change it to one which sounded more feminine. I respected that; I respected her right to change her own name for her own reasons. Though I did personally like her birth name, I felt it was important to be respectful of her choices and show my support, and so I switched over to using her new preferred name straight away. I still slipped up sometimes, of course; but I caught myself, corrected myself and apologised, and she didn’t mind because she knew that I was generally on board with the idea. Now, a few years down the line, it’s actively more difficult to use her birth name, because I’ve become so used to using her preferred name. That is who she is now, and I can’t imagine thinking otherwise.

At the time when she first made the change, I applauded her courage and her conviction. I thought, wow! That’s so cool. I wish I could do that.

But even while rooting my friend on as she changed her name, I didn’t know what to do about my own name. I knew I didn’t like “Stacey” or “Stacie”, though the latter was still better — or, I should say, not as bad. But I didn’t know what I did like.

There was only one thing I did like about my birth name: its meaning of “resurrection”. The theme of resurrection and rebirth was an important one to me; especially in my teenage years as I fought my way through a difficult place, struggling every day for my survival. Eventually, I came out the other side even stronger. But it was particularly relevant for me at that time of my life when I was dealing with death and thoughts of destruction. It became a central theme for my stories; the idea that I, too, could make a new life for myself and be reborn, just as my name suggested. The importance of this can be seen in Chapter One of my story, Evani’s Awakening (also known as Headstory, under its working title):

Evani took a deep breath. “If you know everything, then…” She hesitated, nervously twisting the material of her skirt in her hands before continuing. “Please tell me why I am here. Why was I not sent to the Seventh Circle like the others…?”

“Ah. Well, you are part of a prophecy,” Lucifer replied. “‘The wayward son will fall into the darkness, but the Lord will raise him; and from the darkness, he will bring new light. His physical body will be raised again a spiritual body, and he will return to the world of man a Saviour.’ That is your role. You will not be punished for your suicide, for you will return to Earth to realise your true purpose […] That is why I said the name ‘Stacie’ was fitting, for it means ‘resurrection’.”

—Excerpt from Chapter One of Evani’s Awakening

That emotional significance was the reason why, when I was searching for a new name, I also searched for names with a similar meaning. But I hit many dead ends. There are many names which mean “new day”, “new life”, or convey a sense of “new beginnings”; but none of those names appealed to me. None of them hit home.

Luckily, I had a good friend to talk to about it and bat ideas around with. I told him I had looked up names which also meant “resurrection” or “rebirth”, and he agreed that it was a perfect sentiment. His response was, “Omg, that’s perfect! Look at it and your situation!”; but he also agreed that finding names which meant the same and still sounded right was hard. So then he came up with the idea of “What about redemption instead of resurrection? I think you already resurrected, no?”

I liked that idea, because it seemed apt. I had gone through a period of darkness and rebirth. I had come out on the other side. That was now in the past. I had no need of resurrection anymore; it had already happened.

Together, we cycled through some more ideas where nothing stood out to us; and came back around to the idea of doing something with “Evan” or “Evani”, given that those were already names for myself I did use and did like. He said that he liked “Evani”, and that it suited me: but he also asked if it felt perfect for me; whether it called me; whether I felt it in my soul.

I answered with, “It's more my name than anything else”; and that it could very well be that nothing else seemed to fit because I already had “Evani”. We talked about names some more and he talked about online names and character names he had come up with for himself. When I said how much I liked his name because of how it suited him and the symbolism/ associations I had with it, he said, “You make it sound prettier than its origin story! You’re great at stuff like that [finding symbolism], so I’m sure you’ll find yourself a great name.”

We ended up talking about names for a long time, but he gave me a lot to think about and a lot of inspiration. Thanks to him, I stopped looking for names which were like “Stacey”. I stopped looking for names which meant “resurrection”. I stopped looking for names which tied me to the past, and instead looked forward to the present. I looked at the names I had already chosen for myself at various points in my life, and what they represented for me and the symbolism they held.

And all that led me to picking “Ievan”, a rearranging of “Evani” — the name I used as my online handle. I liked the name “Ievan” because it could be paired with “Evani”, and either be used separately as a counterpart or put together to form “Ievani”, creating an amalgamation which incorporated both distinct names wholly and completely and yet could be read separately, which featured a lot of overlap between two separate-but-similar personas.

Now I am very happy with “Ievan”, in a way I never was with “Stacey”. Now, I smile when people use my name where I used to cringe.

My friend who changed her name had to go from a “boy’s name” to a “girl’s name” to find happiness. For me, it was the opposite: I had to change from what was typically a girl’s name (with some masculine connotations), to what is typically a boy’s name (with some feminine connotations — ie, the extra ‘i’, which I consider to make the name appear more feminine than it would without it.)

Before I could find my name, I had to find myself. Now I know I would never have been happy with “a girl’s name”, because I am not a girl. I had to accept myself, proudly and fully, as non-binary, so that I could find the right name for me not as a woman, but as a person. To lessen the dysphoria, what I needed was something that was neither exclusively feminine or masculine, but a blend of both. “Ievan” is an unconventional name for an unconventional person; and that is why it fits me perfectly. It replaces all the dysphoria I had previously felt with euphoria instead.

I just had to open my mind and actually allow myself those possibilities.

2 notes

·

View notes