#HubertvanEyck

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hubert van Eyck

The boldest claim for connoisseurship is that it can sometimes resurrect an artist from the version of death that is oblivion or neglect. There is one outstanding example of this, outstanding in both senses, because the artist was no mediocrity but a pioneering genius. His name is Hubert van Eyck, the bachelor brother of Jan van Eyck. Hubert died in 1426, at what age is unknown.

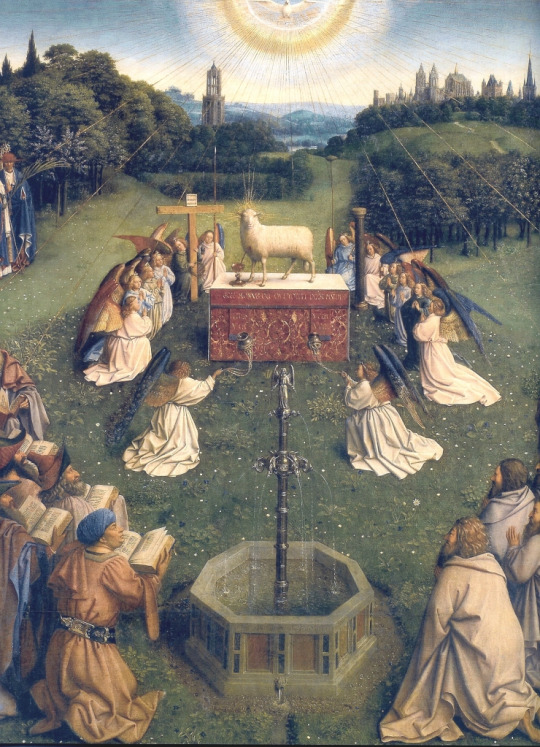

Apportioning work to Hubert and to Jan inevitably begins and ends with consideration of the famous Ghent Altarpiece, The Adoration of the Lamb, which was painted for St Bavo's Cathedral at Ghent and has remained there ever since, bar one stolen panel replaced with a replica.

The Ghent Altarpiece, open (St Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium)

The altarpiece, closed view

The division of labour for the altarpiece’s many panels

Hubert’s story is one of posthumous eclipse: Jan’s work simply covers over and obliterates his brother’s. When eminent scholars have wondered if Hubert’s hand is even discernible in the Altarpiece, his very existence begins to be questioned. Jan’s work, meanwhile, becomes so extensive that one can scarcely believe it possible that so much meticulous, labour-intensive painting could be done in one lifetime by one man. Accepting, as I do, that Hubert did exist and did paint parts of that Altarpiece, I need to say at the outset that I find no particular difficulty in recognising which parts are his and which parts are Jan’s. I believe that Hubert painted all the lower panels of the opened Altarpiece and the four arched panels of it closed. The rest, for me, is Jan’s. Did he take over, and complete, what Hubert had begun?

As we shall see later, another difference between the brothers is that Jan cares about individuals; it is he who paints the portraits of the donors on the Altarpiece and has left us a handful of other painted portraits. Hubert includes many people in his work, but they belong to a repertoire of types, chosen and combined according to need. Survival involves much accident, but i am not sure that he has left us more than one independent portrait.

Hubert’s panels from the opened altarpiece, including the Adoration of the Lamb

Hubert’s panels from the closed altarpiece

There are different elements involved in this distribution and in the distinction drawn by it between two brothers who were both miniaturist in their technique but very different in other ways. Jan’s vision of the world was monumental in the sense that he could create grand figures that occupy a space sculpturally, but the space that they occupy is typically an indoor one This is often quite confined, but even where it is not - say in a church - it is of a kind to make a backdrop to figures which have a looming foreground presence. Such figures serenely dominate the space in a manner that is regal, befitting the Queen of Heaven, Angels, Saints, Sometimes, like real sculptures, they fill niches. By contrast, Hubert’s essential identity as an artist is that of a landscapist The space between him and the horizon is a need of his spirit; he does not want to be confined by walls or to see what delights him only through windows.

The Brothers in side-by-side – Hubert’s talent for creating small forms in big spaces, like the Adoration of the Lamb, stands in contrast to Jan’s preference for setting big forms in small spaces. Both of the above images feature cities in the background, but Jan has set his Annunciation in an enclosed space.

Virgin and Child – ‘The Ince Hall Madonna’ (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne)

Jan, then, is a chamber artist, like Vermeer. Take his early Madonna Enthroned, a small picture at Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria. The light visits her through the window and illuminates particularly a bit of wall to her right: this passage is pure Vermeer, two hundred years before he, too, immortalised the female presence in an indoor space lit from without. Already in the illuminations of the Turin Hours which I follow Kenneth Clark in giving mainly to Hubert - he is evincing a totally different take on the world, one that revels in a storm at sea, a calm lakeside, or the long line of a coast. He can make us feel the cold salt air and see the waves rolling in onto a low shore where a Duke and his entourage have landed and ride up the dunes on their way to his castle. Faced with painting figures in a room or a church, however, and one immediately senses that Hubert, at that stage, is less at ease, his discomposure evident in a relative lack of both atmosphere and compositional unity.

Miniature illustrations from the Turin Hours. Clockwise from top left: Agony in the Garden; The Cavalcade (destroyed); Baptism; Office of the Dead; Miracle of Sts Julian and Martha. All surviving works Palazzo Madama, Turin

LANDSCAPE

The Crucifixion and The Last Judgement (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Further evidence of Hubert’s interest in landscape can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum in New York; here we find the Channel coast again, the rollers coming in onto long stretches of what are now Belgian beaches. The sea is a Prussian blue - a shade that Hubert particularly loves - with drowning souls in it pleading to be saved, like their luckier compatriots on land, from the horrors of Hell beneath. In the left-hand panel is an early version of a typical Hubert landscape: middle distance warmth of foothills and human habitation receding to a far range of blue mountains fading into blue sky, and all in clearest visibility (atmospheric sfumato still unborn). Both panels are crowded with people dead and alive, but the landscapes complement the crowdedness with an airiness and spatial largesse that is all-inclusive and ruffled only by some fretted cumulus and fretted waves. There are many colours, but they answer each other across the panels as might happen in a pair of stained-glass lancets. The correlations are not only chromatic but formal: the rising foothills of the left panel continue into the white lining of the Virgin’s blue robe in the right panel, and the darkness behind the arms of Death spread over into the left panel.

It is Hubert’s gift to give to crowded, jostling humanity so much space around it and so much air above it. As in the lake and coastal scenes of the Turin Hours there is conveyed to us the breathed atmosphere of a huge encompassing space that is beyond, yet all around, whatever is happening in the human world. He is very sensitive to this essentially calming influence of the natural world that is also, for him, a sacred one.

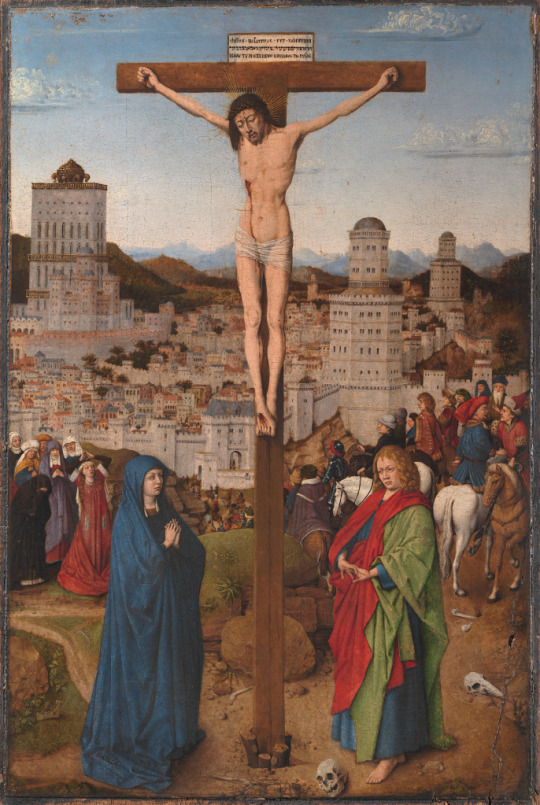

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and Saint John ( Gemäldegalerie, Berlin)

In Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie there is a small Crucifixion with just Mary and John either side of Christ, she downcast and resigned, clasped hands out-turned, John turned away, weeping. The lovely landscape behind seems wintry, echoing the elegiac mood with a tall bare-branched tree; a city lies low amid uneven, intractable terrain, with a backdrop of remote mountains. Close up to the picture plane, the human scene is emotionally near, the viewer forming a fourth witness to a Passion whose outpouring is visible blood, invisible tears. The suffering, with that much haemorrhage, must be over, and the end is a resignation that makes a kind of peace with the larger world, shorn and naked now, but assured of resurrection. The picture illustrates perfectly Hubert’s ability to match landscape with human drama and emotion.

Crucifixion, National Museum of Poznan, Poland

In another Crucifixion, at National Museum in Poznan, Poland, crowded onlookers react in their different ways to the anguish on the Crosses. Again the landscape is important; no mountains, but a backdrop of partly wooded hills below a sky of scudding cumulus moving along with an event that is still unfolding, a Passion not yet spent.

Crucifixion, Ca d’Oro, Venice (attrib Hubert v Eyck or school of J v Eyck)

A late Crucifixion at the Ca d’ora in Venice shows the same out-turned hands we saw in Berlin, this time on John. This Crucifixion represents a substantial departure from earlier ones. Christ seems lifted high above Mary and John, while the city has come alarmingly close, a threatening source of crowds who are standing around, a little down from the hill of Golgotha. A group of women on the left look up at the back of Christ, while men on the right, on horseback, look in other directions as if the show they came to see is finally over. As for the city, it encourages Hubert to flights of architectural fantasy. Three structures of Babel-like height and mass tower over the huddled houses, more out of scale than even the real-life cathedrals were in Hubert’s day or the skyscrapers in ours. Either side of lonely Pathos, Hubris is rising ever higher.The division of women to the left of the Cross, men to the right of it, signals a contrast, almost a contest, between compassion and indifference; but the triangle made by the feet of Christ and the hands of Mary and John - reversing that made by the arms of Christ and the crossbar of the Rood - marks the personal, almost private and familial nature of the event at this late stage when onlookers begin to look elsewhere.

St Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Detail of rocks

In the Johnson Collection at Philadelphia's Museum of Art we are with Saint Francis kneeling among rocks before his vision of the crucified Christ. The theme of wakefulness and sleeping that was there in the Gethsemane of the Turin Hours has returned with a difference. Here colour is used to suggest, not the contrast between people and their surroundings, but a Franciscan harmony between them. The Saint is clothed in the brown habit of the wilderness in which he prays, while his Brother, linked to him by the cords of their shared vows, is lost in sleep or meditation. What unites this image with the far cooler and more distanced Gethsemane is the treatment of rocks, well in advance of Leonardo’s studies, but no less beautifully observed.

Left: St Christopher Carrying the Infant Christ, Phildelphia Museum of Art; Right: Copy of a lost drawing attributed to J v Eyck of the same scene, Louvre Museum, Paris

Rocks bring us back to Philadelphia, to an exquisite small Saint Christopher carrying the Christchild through shallow water between towering cliffs sprouting trees and bushes. Behind the Child is a lake with distant mountains. Most notable here is the painting of the foreground water - a painterly achievement not attempted in the associated drawing at the Louvre. Such an understanding of water, its surface and depth, the way it moves under pressure of wind and current, is astonishing at so early a date, though we already saw it at Turin, in the Storm on Galilee. There seems to be nothing in the natural world of which Hubert has not made himself master, always on a small scale and with that miniaturist technique that he shared with his brother. We see a mediaeval inheritance being used to quite new ends, and taken to the height of realistic fidelity in a medium that we have to remind ourselves was still in its infancy, What he does is breathtaking in its virtuosity, but also very affecting in its sensitivity and delicacy of touch. he applies his brush as finely as the bow of the most accomplished string player.

Three Maries at the Tomb, Boijmans Museum, Rotterdam

In connection with landscape the last work I want to consider before the Ghent Altarpiece is his painting at Rotterdam's Boijmans Museum, the Three Maries at the Sepulchre.Here, more than ever, we see him using landscape and sky to reinforce a human story. It is not so much a nocturne as an aubade, an evocation of night becoming dawn, well before the sun is up; the sky begins to lighten but night still pervades. The soldiers are asleep, the women are awake; the Angel. like Aurora, female, winged. It is a ghostly hour. The weapons of day, the active life of men, are laid aside as diagonals around the rectangle of the Sepulchre. Beyond that is the still-slumbering city, its towers pushing up into the sky like pinnacles of rock, the bedrock on which the whole scene rests. Like the magician that he is, Hubert can cast a spell of nocturnal obliviousness over what in daylight would be local colours, leaving only certain reserved accents of white in the middle band of the composition - the women’s headdresses, Angel’s robe, a man’s socks - to denote the wakefulness heralded by the whitening sky and a Resurrection on Earth within the Resurrection of Light.

Drapery details from Ghent’s altar of the lamb can be compared with those of the angel’s robes in the Three Maries

We have arrived now at that heavenly vision that is Hubert’s contribution to the Ghent Altarpiece.The daisies around the feet of Saint Francis, at Philadelphia, return in the grassy bank around the Altar of the Lamb, and there too the drapery of those angels falls in folds like those of the Angel on the Sepulchre at Rotterdam. As in the panels in New York, we find groups crowded together but here transformed into outdoor choirs in a landscape that holds them generously; there is ample space between them in which our eye can move around freely, like a bee, alighting on ever more extraordinary detail. The landscape is idealised, yet recognisably a northern one, of rolling hills and woods between prosperous, aspiring towns, all transformed into a Paradise Garden where every leaf and petal counts and towns become Jerusalems, Cities on the Hill.

On Hubert’s landscape sensibility I have surely said enough to convey how exceptional I think it was and to highlight especially (since landscape was not yet an independent genre) his ability to make it echo sympathetically the pathos of a Crucifixion or other human enactment. His brother also had very considerable gifts when landscape was required, but this particular marriage of mood is not evident in his work; his forte is indoors. If Jan could not have painted The Women at the Sepulchre, Hubert could not have painted the Arnolfini picture. If Hubert’s favourite subject was the Crucifixion in a landscape, Jan’s was the Enthroned Madonna in a room, The contrast between their powers is what my division of labour in the Ghent Altarpiece makes eloquent, There exist some polyptychs, later and elsewhere, that are a mixture of two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture. The Ghent Altarpiece is all painting, but something of that difference is there: Jan’s large figures possess the physicality of sculpture in the round, while Hubert shows himself as more purely a painter. Nothing in Hubert’s contribution reminds one of that; it consummates his love of space and landscape, while the figures, of which there are many, exhibit a variety of facial types significantly different from Jan’s.It is to these that I now turn.

LANDSCAPE WITH FIGURES

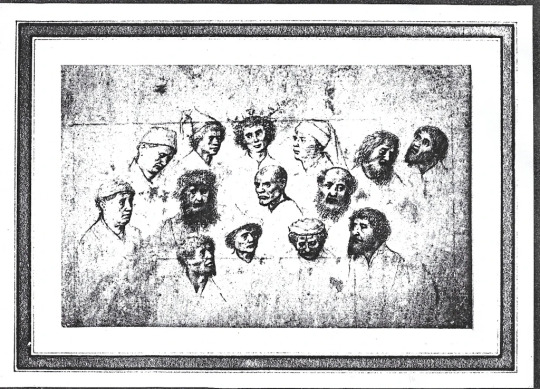

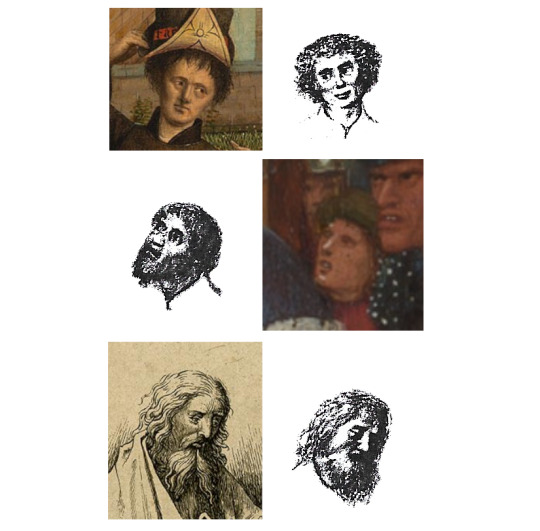

A series of studies of fourteen heads of men, some thought to be for ‘The Adoration of the Shepherds’, variously attributed to J v Eyck and Gerard David

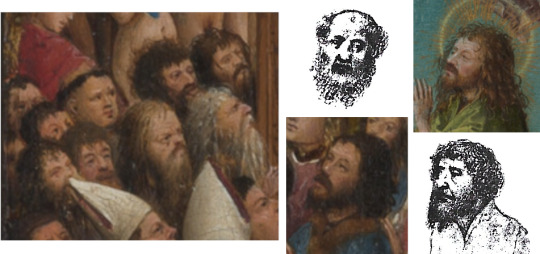

It is fortunate that in the Berlin Print Room there is a sheet of drawn heads that provides exactly what we need. Given the similarities which I shall illustrate, there is no doubt in my mind that this sheet is by Hubert and not by Gerard David or any later artist.

It is helpful to number these heads, so that we can refer to them individually in relation to paintings. Head number 4, for example, reappears as the central figure in a panel at the Boijmans Museum at Rotterdam depicting Saint Catherine led away to her Martyrdom.

in one of a pair of panels at Rotterdam attributed to the ‘Southern Netherlands School’ but much more convincingly to Hubert, albeit in a relatively early phase of his career as a painter of individual panels. This is one of a pair, the companion being Saint Catherine preaching to the Emperor, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Already in these panels we encounter certain Hubertian traits, elaborate metallic tiaras and complicated headgear, the beginning of that fascination with flowered lawn, the springing leaves of grass touched in with the fine tip of the brush, and also hand gestures, witness the left hand of the Saint in the other panel at Rotterdam and the right hand of the Virgin Annunciate in Washington.

Left: St Catherine Preaching to the Emperor, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and its apparent pair, Right: St Catherine Carried Away to be Beheaded, Boijmans Museum, Rotterdam

Comparing the hands of the Virgin the Annunciation at Washington with the hands of the Emperor

Heads numbers 10 and 14 are basically the same head at different angles, and he is a character who appears, wearing dark prussian blue, above the sea in the righthand panel at New York, in the head of Saint John (in green), and several times on the opposite side of the same panel, above the bishops. Number 7, the central head of the drawing, appears on the left panel, on the extreme right, below the left leg of the righthand thief on his cross.

The heads from the earlier chalk study appear in the Crucifixion and Last Judgement panels

These correspondences suggest to me that the Berlin drawing may be contemporary with the New York panels, but the types, which are not Jan’s, recur in different contexts later, which is why I regard the drawing as a helpful index to Hubert’s characterisation.It only represents a few types (or ‘tronies’); the full repertoire, as demonstrated at Ghent, is more extensive. Number 9, to mention another that is very common in Hubert’s work, is well represented at the Albertina in Vienna by the drawing of Saint Andrew holding his Cross.

More heads can be found in St Catherine Carried Away, the Last Judgement and in a drawing depicting St Andrew

All this is not to say that Hubert only did landscapes and Jan only interiors, as we can see in these two examples: the first is Hubert’s tall Annunciation in the Mellon Collection at the National Gallery of Washington and on Jan’s side the Louvre Madonna with Chancellor Rolin.

The Annunciation, attrib Jan van Eyck, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Madonna of Chancellor Rollin, Jan van Eyck, Louvre

Neither Hubert’s smiling Angel nor his Virgin is as Jan would have painted them. The general brownness of the cathedral’s architecture and pavement (reminiscent of the ‘pensive’ brown of the Saint Francis) beautifully conveys the dim stillness of the lofty church, the privacy of reflection, and how revelation, in that ambience, is a matter of inward illumination. The Virgin does not face the Angel nor us, she tilts her head and looks to our right, her gaze on the axis of the dove’s silent swoop. The illumination is in the robe and wings of the Angel, the same colours that are in the stained glass of the window above the Virgin’s head. As in the landscapes, the dim, airy interior of the church matches exactly the mood and moment of the scene enacted; natural and supernatural , visible and invisible, fuse into one.

Facial features in Veronica’s Veil at the Phildelphia Museum of Art can be compared with those of the Virgin from the Annunciation at the National Gallery in Washington

Before leaving this Annunciation it is pertinent to mention a Head of Christ, presented as a Veronica Veil, in the Johnson Collection at Philadelphia, which I give to Hubert. I leave the eyes of the reader to match its features with those of the Virgin.

Drapery is something connoisseurs have to get to know in all its rhythmic convolutions, and nowhere more so than in Netherlandish art where the representation of it reaches astonishing levels of virtuosity in some artists and is always subtly different through whatever hand it is expressed. The ridges and valleys of falling and spreading drapery begin to constitute a landscape in themselves. It is important, therefore to consider Hubert’s own treatment of it which is not greatly different from his brother’s, but subtly so.

Left: Lost illustration of the Virgin and Child from the Turin Hours; Right: The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine, Germanisches National Museum, Nuremberg

Back at Turin, one of the illuminations in the Hours is this one of the Virgin with her Child surrounded by female Saints. The drapery, spreading like foam on a beach onto the flowery meadow, is archetypical of Hubert: very fluent and supple with quite wide spaces between the ridges. We can see this more confidently expressed in a splendid drawing from Nuremberg, of the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine.The sparse folds and rhythms are more pronounced because much later, perhaps even contemporary with his work on the Ghent Altarpiece; the types, female and male, that flank the central group in the drawing are recognisable in the various groups of its painted figures. In the Ince Hall Madonna at Melbourne Jan comes closest to Hubert in the fall of folds that swirl about her, but his drapery later on becomes much more like the painted equivalent of lime wood carving as in the large figures at Ghent.This reflects the difference already noted: Jan tending increasingly towards sculptural monumentality, Hubert remaining more essentially a painter.

Left: Madonna at the Fountain, Hubert van Eyck; Right: Madonna at the Fountain, Jan van Eyck, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

I have made the point that Hubert was more interested in landscape, Jan in the indoor world. This is nicely illustrated by each of them painting a version of the same subject, the Virgin and Child standing by a Fountain. Hubert places Mother and Child wholly outdoors, grass and flowers at her feet and a bosky background of trees and shrubbery behind a low brick wall. Jan has the Virgin stood on a rich backdrop of brocade that is held up by angels. Yes, there is a rose hedge, low wall, flower-spangled lawn, but it is noticeable how the gold foliage on the brocade is assimilated to the real foliage and real flowers behind and below. Similarly at the top there is assimilation of the angels’ red and gold to the red and gold of the brocade whose edging continues into the edging of their wings. In other words an indoor prop, the brocade, signals that the Virgin and her Child are only half outdoors.

The Annunciation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A picture that may well belong to the period of the Hubert Madonna at the Fountain is the Annunciation at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, with Mary standing at the doorstep of a lofty portal. Notice the similar treatment in both cases of trees, wall, plants and lawn, as well as the heavy-looking drapery folds in the figure of Mary.

Left: Queen Isabel (St Elizabeth) of Portugal (attrib Massys et al), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; Right: Cumaen Sibyl from the Ghent Altar

At the beginning of this Study I proposed a very simple division of Hubert’s and Jan’s contributions to the Ghent Altarpiece: all the lower tier of the opened polyptych is Hubert’s, plus, when it is closed, the four arched panels at the top. The latter are interesting because at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin there is a little-known, little-discussed panel of the Holy Elizabeth of Portugal, attributed at times to Quentin Massys and also, vaguely, to a Portuguese-Spanish master, and dated around 1500. To my eye it belongs in an earlier period and its rightful home is in the work of Hubert van Eyck. The head should be compared with that of the Cumaean Sibyl, the lettering with that of her scroll (or any of the scrolls), the tiara with that on the Angel of the Annunciation, the radiance of the aureole with Hubert’s radiances throughout his career.

Portraiture features prominently in the work of Jan van Eyck. We have five separate portraits as well as those of Arnolfini in the London Marriage picture and Chancellor Rolin in the painting of him and the Virgin at the Louvre. It is not apparent from extant work that the same is true of Hubert. The Berlin drawing of heads is a drawing of types, some the same seen from two angles, and as such it represents part of a repertoire of visualised characters who can be introduced into crowd scenes. I may be wrong, but I doubt if many of the heads in the Ghent Altarpiece are portraits. There is, however, one independent portrait that seems different from the Jan portraits and that is the Man in the Blue Cap at the Brukenthal National Museum in Romania. The closest comparison is probably with the heads of the nearest banner-holders on horseback in the Ghent Altarpiece. The vivid Prussian blue is a staple of Hubert’s palette at least as far back as the panels in New York.

Left: Detail of riders from the Ghent panel; Right: Man in a Blue Cap (attrib J v Eyck), Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu, Romania

Naturally, much more could be said (and by others has been) about that complex masterpiece. My concern has been to mark the difference in style and scale between the contributions of the two brothers. They worked in the miniaturist tradition, but they applied their miniaturism - their technical ability to represent very fine detail- in quite different areas. The paradox in Jan’s work is that he actually thought big, not small, in the sense that he conceived large, monumental figures first, and then bestowed on them a wealth of pin-sharp, jewel-like detail. He liked them to fill and dominate the space he gives them, even to the point of making them seem too small for it, as in the Angel and the Virgin in the Ghent Annunciation, both of them large presences in a low-ceilinged room.

Left: Detail from the Ghent Annunciation; Centre: The Virgin of Canon van der Paele, Groeningemuseum, Bruges; Lucca Madonna, Frankfurt

Hubert is the converse of Jan: his figurative scale is smaller, as befits a landscapist, but his spatial scale is vast, as we have seen. Along with the Limbourg brothers and Jean Fouquet, Hubert stands at the beginning of the long story of European landscape art. Part of what distinguishes Hubert in this tradition is what I would call his sympathetic landscape, one that reinforces the human story. When landscape eventually, but gradually, becomes an independent genre, this accord gets lost; not entirely because Poussin is a master of it. In a Claude landscape Aeneas seems an introduced character, adding an extra mythological element to an idealised pastoral; the same is true of Hannibal or Polyphemus in a Turner. In Hubert’s day Man and Nature could be seen together in a vision that sacralises both. That vision involved huge distances, great depth of aerial perspective. After the flatness and abstraction of the twentieth century we have difficulty, pictorially, giving expression to such spatial awareness; a nostalgia can creep into our appreciation of Hubert’s art. We must find new ways.

In view of Hubert’s prodigious talent it is fairly shocking that his art has been so eclipsed by Jan's, so comprehensively overlooked. There should be as many monographs and picture books, articles and exhibitions about him as there are about Jan, but there are not. Ask any person of average visual culture about Jan and the name and some works - probably the Arnolfini picture - will be familiar. Ask about Hubert and the response is a mystified, interrogative ‘Hubert?’ The essential purpose of this Study has been to remove that question mark. Like the remarkable Master of the Pieta de Villeneuve (at the Louvre) Hubert is a great artist whose fate has been to have his work confused with that of another great artist, in the Master’s case with Enguerrand Quarton, in Hubert’s case with his brother. It is in this sense that I claimed for connoisseurship the power, sometimes, to resurrect. The resurrection, however, is not instant or miraculous but a patient, collective process that, once begun, must continue.

Cityscape from the Ghent Altarpiece

Just to scroll back through the coloured illustrations of this Study is to be reminded of medieval illuminations, their bright, unfaded, undarkened colours, and of course their miniaturism. Yet in other ways Hubert looks forward, not backward, moving clear-sightedly out of the Middle Ages into the humanism of the Renaissance and on towards all that followed in our European landscape art. We owe him, I think, a huge debt.

On the subject of debt, I wish to acknowledge here what I owe to Emily Wetherell who has helped me so much, and so tactfully, with this Study and many of its predecessors. Not only has she been the technical assistant to a technophobe, she has done a great deal of picture research, checking the locations and current attributions of pictures and drawings, as well as making numerous suggestions about how to improve the text. Crucial to the visual argument of all these Studies, however, is the juxtaposition of images, and she has contributed materially to making clearer those comparisons and connections that are at the heart of any serious connoisseurship.

#studies in connoisseurship#hubertvaneyck#vaneyck#jan van eck#hubert van eyck#art history#connoisseurship#miniatures#turin hours#illumination

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#hubertvaneyck #pierretombale #gand #surarteencemoment https://www.instagram.com/p/CBLuqpzBCau/?igshid=14oax7s9a46f4

0 notes