#House of Capet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Women’s History Meme || Sibling Relationships (1/5) ↬ Berenguela, reina de Léon y de Castilla and Blanca de Castilla, reine de France

Queen Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) was, in her lifetime and for some time thereafter, a dominant figure on the political landscape of the kingdoms of Castile and Leon. She typified the medieval elite woman whose ordained role in life was to be a wife and mother. The political circumstances of her native Castile, however, complicated and even enhanced Berenguela’s reproductive responsibilities. As the eldest daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Leonor of England, Berenguela was at different points in her young life the presumed heir to the throne. The Castilians adhered to the Visigothic principle of partible inheritance. Although favoring sons, this principle meant that daughters had a claim to inheritance. Therefore, it was possible for a woman to inherit the throne when a male heir was lacking as had happened with Alfonso VI’s daughter Urraca in 1109 and with Berenguela in 1217. Berenguela’s awareness of and concern for her own lineage derived not only from a strong, involved identification with her natal family, based on her position as her father’s daughter, but also from her awareness of her own self as an element of that lineage. Her experiences and activities can be usefully contextualized by those of her numerous and important sisters, especially Urraca, Blanche, Leonor, and Constanza. They show ways in which Berenguela was like other elite women; indeed, her life could have turned out very much like one of theirs. Despite their individual circumstances, together they help demonstrate ways in which Berenguela was and was not alone in her experiences of family, marriage, motherhood, religion, and, above all, gender. Furthermore, the sisters were key elements of Berenguela’s family; throughout their lives, they remained in contact, if only for seemingly political reasons at times. Family visits, the fostering of children, and prayers for the dead suggest affective bonds as well as a deep sensibility of filial and sisterly piety among the members of this family. Berenguela’s sister Blanca (1188–1252) is better known as Blanche of Castile, queen of France, one of the most famous women of the Middle Ages. From the time of her marriage to the French heir Louis, Blanche was destined for significance, even if only as another female link in the seemingly miraculous chain of male inheritance that had secured the Capetian throne for generations. Three years after Blanche’s husband Louis became king, he was dead, and Blanche became regent both for her young son, Louis IX, and for the kingdom of France. Blanche became queen of France at a time when the institution of queenship seems to have undergone a shift, becoming increasingly relegated to the private, domestic world of the queen’s own household; at the very least, there is a change in the way documentation presented the queen’s activities at court. Although Blanche’s own political experiences were particular to her Capetian context, examining the several parallels between her experiences and those of her sister Berenguela points to certain consistencies in thirteenth-century royal motherhood and queenship. — Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) and Political Women in the High Middle Ages by Miriam Shadis [old version]

#women's history meme#berengaria of castile#blanche of castile#house of ivrea#house of capet#medieval#spanish history#french history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently reading : The Burgundians: A Vanished Empire by Bart Van Loos

#book photography#books#currently reading#history#medieval france#duchy of burgundy#non fiction#medieval history#house of capet#house of valois

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've said this before, but there's also a part where Dante meet Hugues Capet in hell, whom he portrays as the son of a butcher who usurped the French throne.

That is present because Dante hated Hugues' descendants, Philippe IV of France and Charles, count of Valois, for their constant meddling in Italian affairs. Their meddling was mostly the result of their great-uncle, Charles of Anjou, having become the king of Naples and Sicily with papal approval (though he later lost Sicily to the Aragonese House of Barcelona), but also because Philippe had a dispute with Pope Boniface VIII over his attempts to tax French bishops without papal approval.

Dante’s Inferno is the best piece of classical poetry because it’s the most petty thing you will ever read. Half of Hell is mythological or historical figures and the other half is Dante’s enemies. So the whole thing is like “I am Medea, who slew her own child to spite her husband.” “And I am Francisco di Vincezzino Fabriccia, who gets very talented and handsome poets kicked out of Florence, but I’m very sorry for it now because I’m burning in Hell and I suck.”

#dante alighieri#divine comedy#house of capet#medieval#history#the salt and pettiness levels are off the scale

67K notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail showing the coronation of Queen Jeanne, from the Coronation Book of Charles V, France (Paris), 1365, Cotton Tiberius B. VIII, f. 68r.

#maison capét#house of capet#capet dynasty#reine de france#queen of france#charles v#consort#medieval France#manuscripts#royalty#french royalty#queen joan of france

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Margaret I (1310 – 9 May 1382) was a Capetian princess who ruled as Countess of Burgundy and Artois from 1361 until her death. She was also countess of Flanders, Nevers and Rethel by marriage to Louis I of Flanders, and regent of Flanders during the minority of her son, Louis II, in 1346.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The House of Capet. 987-1328

The Capetian dinasty was the first French dinasty resulting after the death of Louis V (c.967-987) last Frankish king of the Carolingian Empire. In my HC, this Frankish personification is father of both France and HRE, and also Austria. After the colapse of the Carolingian empire, the Kingdom of Francia disappeared and the empire was partitioned in three big territories; West Francia (France), East Francia (HRE) and Middle Francia (the territories that the both of them will be fighting for in the centuries to come, the Benelux spawned from those territorial wars in between them, as well and Switzerland and everything in between).

France and the Holy Roman Empire would become natural enemies, then, as Franco's inheritance would be the same as that of the Carolingian Empire; to become the next Roman Empire. And both kingdoms would spend the rest of the centuries until the World Wars trying to achieve that inherited goal. It has a name, in fact; Franco-German enmity.

Hence, then, the name Holy Roman Empire, from the intentions to become the next great empire uniting the three continents. France is the older son, by the way. The Frank had... a little favoritism towards the youngest, because it was identical to him. And more visibly German, of course. This fueled the competition between the two and the hereditary and historic animosity between the two "princes". It was the Franks that started the monarchical rule, feudalism and the hereditary rule for the sons in Europe. So France, HRE and Austria would be the first princes, haha.

#hetalia#aph fanart#aph france#francis bonnefoy#hws france#historical hetalia#myart#As always this are my HCs based on historical events#no one has to agree with them or anything

250 notes

·

View notes

Note

The split between the duchy and county came about because of a succession dispute. Otte, a younger brother of Hugues Capet, first became Duke of Burgundy by marrying Liutgarde of Chalon, a member of the House of Ivrea. Yet, he died without legitimate progeny and afterwards, most of the Burgundian nobles elected Otte’s younger brother, Henri. Henri then married another member of the House of Ivrea, Gerberge. Henri and Gerberge also had no children, but Gerberge had had a son, Otte-Guillaume, by her first husband.

After Henri’s death, a succession war broke out between Otte-Guillaume and Robert II of France, Henri’s fraternal nephew. The succession war ended with a partition; Robert II got the duchy, but Otte-Guillaume other lands that were later dubbed the Free County of Burgundy. One of Robert II’s younger sons, Robert Tête-Hardi, was then made the Duke of Burgundy by his older brother, Henri I of France, as a way to placate him and not fight for the French throne anymore.

Robert Tête-Hardi’s last agnatic male descendant was Philippe of Rouvres, who was also the heir to the Free County of Burgundy because his paternal grandmother was Jeanne III, Countess of Burgundy, one of the daughters of Philippe V of France and Jeanne II, Countess of Burgundy. Philippe, however, then died either of a horse-riding accident or bubonic plague. The county of Burgundy passed to his aunt, Marguerite, who was the mother of the Count of Flanders, Louis II. Meanwhile, the duchy of Burgundy was successfully claimed by Jean II of France, because his mother was Jeanne the Lame of Burgundy. He then gave the duchy of Burgundy to his favorite son, Philippe le Hardi and arranged for Philippe to marry the only daughter of Louis II of Flanders, Marguerite III.

Philippe and Marguerite were the founders of the powerful Valois Duke of Burgundy who culminated in Charles the Bold.

Sorry if it's obvious, but I admit I'm a bit confused on there being both Dukes of Burgundy and also Counts of Burgundy and what's the difference?

Because the medieval border region between France and the HRE can't ever be straightforward and rational, there was both a Duchy and a County of Burgundy. And to make matters more confusing, they were right next to each other:

The most significant political difference between them is that the Duchy of Burgundy was part of the Kingdom of France (although they didn't always agree on that) and the County of Burgundy (better known as the Free County or the Franche-Comté) was part of the Holy Roman Empire.

However, and this is an example of how complicated medieval politics could get, both Burgundies were in personal union under the House of Valois-Burgundy, and thus were part of the Burgundian State that Charles the Bold very much wanted to make the core of his revived, independent, and coequal Kingdom of Burgundy. It didn't work out thanks to the Swiss pikemen and the treacherous Hapsburgs, but it came very close to becoming a thing.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of French Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list is composed of princesses of France until the end of the House of Bourbon; it does not include Bourbon claimants or descendants after 1792.

The average age at first marriage among these women was 15.

Judith of Flanders, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 12 when she married Æthelwulf, King of Wessex in 856 CE

Rothilde, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 19 when she married Roger, Count of Maine in 890 CE

Emma of France, daughter of Robert I: age 27 when she married Rudolph of France in 921 CE

Matilda of France, daughter of Louis IV: age 21 when she married Conrad I of Burgundy in 964 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Reginar IV of Hainault in 996 CE

Gisela of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Hugh of Ponthieu in 994 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Robert II: age 13 when she married Renauld I, Count of Nevers in 1016 CE

Adela of France, daughter of Robert II: age 18 when she married Richard III of Normandy in 1027 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Philip I: age 16 when she married Hugh I, Count of Troyes in 1094 CE

Cecile of France, daughter of Philip I: age 9 when she married Tancred, Prince of Galilee in 1106 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Louis VI: age 14 when she married Eustace IV, Count of Boulogne in 1140 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry I, Count of Champagne, in 1159 CE

Alice of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Theobald V, Count of Blois in 1164 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry the Young King in 1172 CE

Alys of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 35 when she married William IV of Ponthieu in 1195 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 8 when she married Alexios II Komnenos in 1180 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Philip II: age 13 when she married Philip I of Namur in 1211 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 14 when she married Theobald II of Navarre in 1255 CE

Blanche of France. daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married Ferdinand de la Cerda in 1269 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married John I, Duke of Brabant in 1270 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 19 when she married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy in 1279 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Philip III: age 22 when she married Rudolf III of Austria in 1300 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Philip III: age 20 when she married Edward I of England in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip IV: age 13 when she married Edward II of England in 1308 CE

Joan II of Navarre, daughter of Louis X: age 6 when she married Philip III of Navarre in 1318 CE

Joan III, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Odo IV, Duke of Burgundy in 1318 CE

Margaret I, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Louis I of Flanders in 1320 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip V: age 11 when she married Guigues VIII of Viennois in 1323 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Charles IV: age 17 when she married Philip, Duke of Orleans in 1345 CE

Joan of Valois, daughter of John II: age 9 when she married Charles II of Navarre in 1352 CE

Marie of France, daughter of John II: age 20 when she married Robert I, Duke of Bar in 1364 CE

Isabella, daughter of John II: age 12 when she married Gian Geleazzo Visconti in 1360 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles V: age 8 when she married John of Berry, Count of Montpensier in 1386 CE

Isabella of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 6 when she married Richard II of England in 1396 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VI: age 5 when she married John V, Duke of Brittany in 1396 CE

Michelle of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 14 when she married Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1409 CE

Catherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 19 when she married Henry V of England in 1420 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married Charles I, Duke of Burgundy in 1440 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married John II , Duke of Bourbon in 1447 CE

Yolande of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy in 1452 CE

Magdalena of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Gaston, Prince of Viana in 1461 CE

Anne of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Peter of Bourbon in 1473 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Louis XII in 1476 CE

Claude of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 15 when she married Francis I in 1514 CE

Renée of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 18 when she married Ercole II d'Este in 1528 CE

Madeleine of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 17 when she married James V of Scotland in 1537 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 36 when she married Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy in 1559 CE

Elisabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 13 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1559 CE

Claude of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Charles III, Duke of Lorraine in 1559 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 19 when she married Henry IV in 1572 CE

Elisabeth of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Philip IV of Spain in 1615 CE

Christine of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy in 1619 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 16 when she married Charles I of England in 1625 CE

Louise Élisabeth of France, daughter of Louis XV: age 12 when she married Philip, Duke of Parma in 1739 CE

Marie-Thérèse, daughter of Louis XVI: age 21 when she married Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême in 1799 CE

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

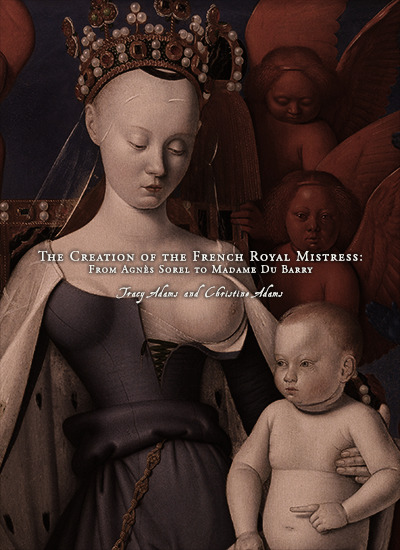

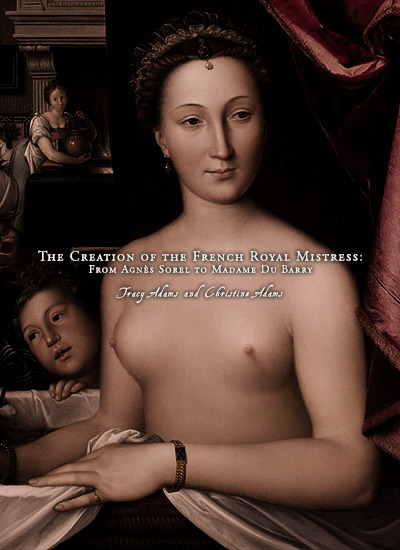

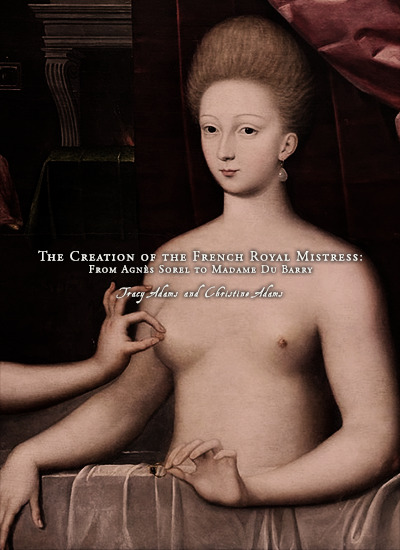

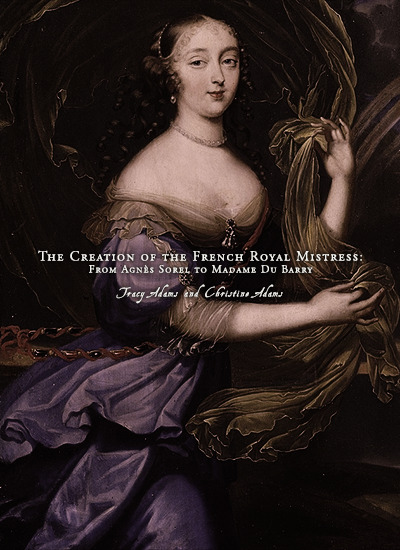

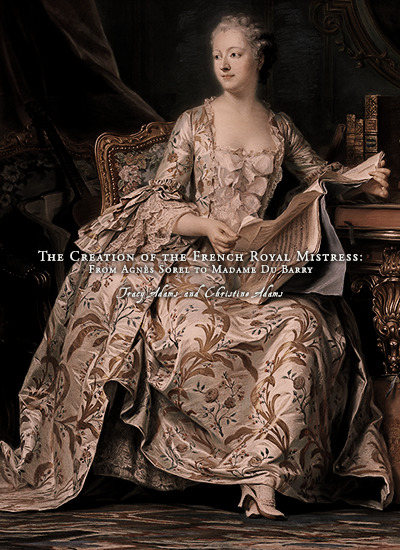

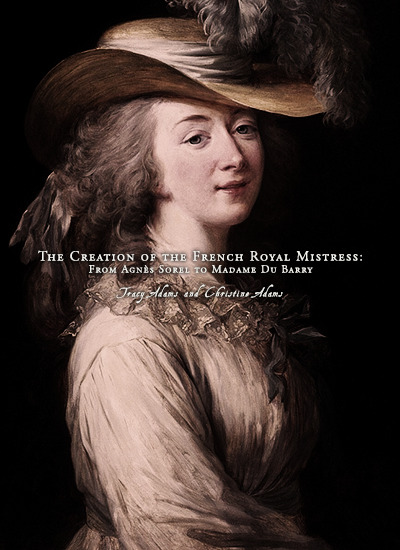

Favorite History Books || The Creation of the French Royal Mistress: From Agnès Sorel to Madame Du Barry by Tracy Adams and Christine Adams ★★★★☆

This study explores the sociogenesis and development of the position in France, examining the careers of nine of its most significant holders: Agnès Sorel, Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, Diane de Poitiers, Gabrielle d’Estrées, Françoise Louise de La Baume Le Blanc, Françoise Athénaïs de Rochechouart de Mortemart, Françoise d’Aubigné, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, and Jeanne Bécu. Although kings had always had extraconjugal sexual partners—some of them powerful, such as Alice Perrers or Jane Shore—only in France did the royal mistress become a tradition, a quasi-institutionalized political position, generally accepted if always vaguely scandalous. And yet the position has been studied only in popular narrative histories intended to titillate. Other powerful female roles central to royal family life, such as the queen, the queen’s entourage, and the female regent, an unofficial role once considered somewhat illegitimate, have received serious attention in recent years, as have individual mistresses. However, the important and enduring position of French royal mistress per se has not been explored.

The study’s point of departure is a simple question: What was it about France? We would like to be very specific about our approach to this question. The creation of the role could be examined from any number of valid and enlightening perspectives. For example, it could be approached through a psychoanalytic lens, to hypothesize about the hidden emotional reasons why the role emerged when it did. Or it could be examined within the context of the Querelle des femmes, that long-term debate over the merits and faults of women, which corresponds, chronologically, to the appearance of the powerful royal mistress in France. However, given our own critical inclinations, we have opted to examine the intellectual, emotional, and physical environment that made emergence of the role possible.

We take as the basis of our analysis Fernand Braudel’s three-part schema of history, which differentiates long- from medium-term structures and both of these from short-term events, and, in this introduction, we initiate the study by applying the schema to the period between 1450 and 1540. Agnès Sorel, often considered to be the first significant French royal mistress, died in 1450; around 1540 Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, the Duchess of Étampes (1508–1580), begins to appear in ambassador reports as a central figure in court politics. As we will see in chapter 1, although indirect evidence attests to Agnès’ political influence, it was not widely recognized during her own time. In contrast, no one doubted Anne de Pisseleu’s power. Between these two dates, then, something occurs that makes it possible for the king’s mistress to be taken seriously as a political adviser.

#historyedit#house of valois#house of capet#french history#european history#women's history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-Portrait – Joachim Wtewael // Self-Portrait – George Frederic Watts // Self-Portrait – Hans Baldung Grien // Self-Portrait – François Grenier de Saint-Martin // Self-Portrait - Anthony Van Dyck // Self-Portrait with Lace Jabot – Maurice Quentin de La Tour // Self-Portrait – Pierre-Auguste Renoir // House on the Shore – Pierre-Auguste Renoir // Self-Portrait – Amanda Sidvall // Self-Portrait – Marie-Gabrielle Capet // Self-Portrait with Palette – Alice Pike Barney // Self-Portrait – Angelica Kauffmann // Self-Portrait with Apron and Brushes – Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowicz // Self-Portrait – Theresa Concordia Mengs // Self-Portrait at an Easel – Sofonisba Anguissola // Alice Roosevelt Longworth – Alice Pike Barney

#amanda sidvall#marie gabrielle capet#alice pike barney#angelica kauffmann#anna bilińska bohdanowicz#theresa concordia mengs#sofonisba anguissola#you're just a boy (and i'm kinda the man)#yjabaiktm#the good witch#the good witch maisie peters#maisie peters the good witch#maisie peters#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

isabelle of the house of capet. the tender. the cruel. the eternal.

dossier. connections. plots. starters. aesthetic.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France"

The hour that struck the death of Louis VIII was arguably the most critical in the history of the Capetian family. The new king, one day to be St Louis, was still a child. The trend of events in the previous two reigns had brought the higher nobility to realise that its independence would soon be seriously threatened. But a unique opportunity was raised to the regency of the queen-mother, Blanche of Castile, on the pretext that she was a woman and a foreigner. Yet this was not the first occasion on which the king's widow had acted as regent, nor the first on which a queen had played a part in politics. Philip Augustus had been the first Capetian not to involve his wife in the government of his realm. Before his time the queens of France had often intervened in affairs of state. Constance of Arles, not content with making married life difficult for Robert the Pious, had wanted to change the order of succession to the throne. She had led the opposition to Henri I, provoking and upholding his brothers against him, and she was perhaps responsible for the separation of Burgundy from the royal domain, to which Robert the Pious had joined it. Anna of Kiev, after the death of her husband Henri I, had been one of the regents, and it was only her second marriage, to Raoul de Crépy, that took her out of politics. Bertrada de Montfort's influence over Philip I had been notorious, and so had her hostility to the heir to the throne, whom she had even been accused of trying to poison. Adelaide of Maurienne, despite a physical personality before which Count Baldwin III of Hainault is said to have recoiled, had held considerable sway over Louis VI, procuring the disgrace of the chancellor, Etienne de Garlande, and egging on Louis to the Flemish adventure from which her brother-in-law, William Clito, was to profit so much. Eleanor of Aquitaine- as St Bernard had complained- had more power than anyone else over Louis VII as long as their marriage lasted. Louis VII's third wife, Adela of Champagne, had appealed to the king of England for help against her son Philip Augustus when he had sought to free himself of the tutelage of her brothers of Champagne. Later, reconciled with Philip, Adela had been regent during his absence from France on crusade. From the beginnings of Capet rule, the queens of France had enjoyed substantial influence over their husbands and over royal policy.

But Blanche of Castile was to play a greater role than any of her predecessors. To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France. For from 1226 until her death in 1252 she governed the kingdom. Twice she was regent: from 1226 to 1234, while Louis IX was a minor, and from 1248 to 1252 during his first absence on crusade. Between 1234 and 1248 Blanche bore no official title, but her power was no less effective. Severe in personality, heroic in stature, this Spanish princess took control of the fortunes of the dynasty and the kingdom in outstandingly difficult circumstances. For in 1226 there arose the most redoubtable coalition of great barons which the House of Capet ever had to face. Loyalty to the crown, so constant a feature of the past, seemed to be in eclipse. This was at any rate true of the barons who revolted, for they appear to have tried to seize the person of the young king himself- an attempt without parallel in Capetian history.

Blanche of Castile threw herself energetically into the struggle over her son and his throne. Taking her father-in-law, Philip Augustus, as her model, she won over half her enemies by craft, vigorously gave battle to the rest, and enlisted the alliance of the Church, including the Pope himself, and of the burgess class, which in marked fashion took the side of the royal family. Blanche was able to fend off Henry III of England, who tried to take the opportunity of recovering his ancestral lands, lost by John to Philip Augustus. She broke up the baronial coalition and reduced to submission the most dangerous of the rebels, Peter Mauclerc, Count of Brittany, and Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse. She adroitly took advantage of her victory to re-establish- this time definitively- the royal power in the south of France: her son Alphonse was married to the daughter and heiress of Raymond of Toulouse. The way was now open for the union of all Raymond's rich patrimony with the royal domain.

The Capetian monarchy emerged all the stronger from a crisis which had threatened to overwhelm it. Blanche felt it her duty not to rest on her laurels. After her son came of age she continued to make herself responsible for good and stable government. By the force of her example she drove home the lessons which Philip Augustus seems to have wanted to press upon his grandson when they had talked together. To Blanche's initiative must be credited the measures taken to suppress the dangerous revolt of Trencavel in Languedoc, as also those taken to defeat the coalition broken up after the battle of Saintes. On these occasions Louis IX did no more than carry out his mother's policy. When he went off on crusade, Blanche one more officially shouldered the government of the kingdom. She maintained law and order, prevented the further outbreak of war with England, and successfully pressed on with the policy which was to lead to the annexation of Languedoc. Likewise it was she who refurnished her son's crusade with men and money, and she took all the steps necessary for the safety of the kingdom when Louis was captured in Egypt.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France- Monarchy and Nation (987-1328)

#xiii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#regents#louis viii#louis ix#philippe ii#constance d'arles#robert ii#henri i#anne de kiev#philippe i#bertrade de montfort#adélaïde de savoie#louis vii#étienne de garlande#st bernard#aliénor d'aquitaine#adèle de champagne

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hugues Capét, Roi de France [987-996]

#house of capét#capetien dinastie#capet dynasty#Hugh Capet#Hugues Capét#medieval France#mediæval France#moodboard

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

what's the point if you can't show off your family wealth by making all of your neighboors see how nice your carpets are like this

i will never understand the north american obsession with carpeted floors. you can't take them out to wash them, all of them are some blandest shade of beige or gray which will never make your neighboors envious even if you could wash them outside in your yard, they gather so much shit in them and are such an uncomfortable texture. every north american household would benefit so much from a persian carpet or at least an immitation of it

#there's a story of a mother forbiding her daughter to marry a man because his house was positioned in such a way that nobody could see her#freshly washed capets in thr yard#ura.txt

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun Fact: Part 1 Study French History EDUCATION for Salma Hayek and Laetitia Casta:

Question:

What were the main dynasties that fought for power in France during the era of the French monarchies, and what were their ruling periods (with specific dates and centuries)?

ChatGPT Answer:

Several dynasties vied for power during France's long history of monarchy, with many different houses rising and falling over the centuries. Here’s a list of the most notable dynasties that fought for power or ruled in France during the era of the French monarchies:

1. Merovingian Dynasty (c. 457–751)

The first Frankish dynasty, founded by Clovis I, who unified much of modern-day France.

The Merovingians were eventually displaced by their own "mayors of the palace" (chief ministers) from the Carolingian dynasty.

2. Carolingian Dynasty (751–987)

Founded by Charlemagne's father, Pepin the Short, the Carolingians were prominent rulers in France and the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne expanded the Frankish empire and became the first Holy Roman Emperor.

The Carolingian power diminished after the Treaty of Verdun (843) split the empire among Charlemagne's grandsons.

3. Capetian Dynasty (987–1328)

The longest-ruling dynasty in French history, starting with Hugh Capet in 987.

The Capetians maintained power for centuries, with an unbroken male line of succession, laying the foundation for the modern French state.

4. House of Valois (1328–1589)

A cadet branch of the Capetians, the Valois dynasty came to power after the death of the last direct Capetian king.

It was during the Valois reign that France saw internal strife, including the Hundred Years' War against England and religious conflicts between Catholics and Huguenots (French Protestants).

5. House of Bourbon (1589–1792, 1814–1830)

Another cadet branch of the Capetians, the Bourbons came to power after the extinction of the Valois line with King Henry IV.

The Bourbons ruled during the absolutist era, exemplified by Louis XIV, the "Sun King."

The dynasty was briefly overthrown during the French Revolution (1789–1792) and returned after Napoleon's downfall, only to be deposed again during the 1830 July Revolution.

6. House of Bonaparte (1804–1814, 1815, 1852–1870)

The Bonaparte family, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, seized power after the French Revolution.

Napoleon declared himself Emperor of the French in 1804, establishing the First French Empire.

After a brief restoration of the Bourbons (1814–1815), Napoleon returned during the Hundred Days in 1815 before his final defeat.

Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon, later became Emperor Napoleon III, establishing the Second French Empire (1852–1870).

7. House of Orléans (1830–1848)

A junior branch of the Bourbon dynasty, the House of Orléans rose to power during the July Revolution of 1830 when Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, was proclaimed "King of the French."

His reign is known as the July Monarchy, which ended with the 1848 revolution that led to the establishment of the French Second Republic.

These dynasties each played crucial roles in shaping the history of France through their political struggles, territorial expansions, and involvement in conflicts both domestic and international.

0 notes

Text

Welcome to Raven’s Peak, M, we’re excited to have you! Isabelle Capet (Vampire, Phia Saban) has been accepted. Please be sure to stop by the CHECKLIST for the follow list, tags to track, and other reminders.

OUT OF CHARACTER

NAME: M. PRONOUNS: she/her. AGE: 21. TIMEZONE: GMT+1.

IN CHARACTER

FULL NAME: Isabelle Capet. SPECIES: vampire. AGE: 23 / 814. DATE OF BIRTH: 1st of May, 1210. GENDER IDENTITY: cisgender female. NEIGHBORHOOD: Hidden Hills OCCUPATION: socialite / none. WORKPLACE: none. POSITIVE TRAITS: attentive, sympathetic, generous. NEGATIVE TRAITS: mercurial, sadistic, domineering. LENGTH OF TIME IN RAVEN’S PEAK: one week. FACE CLAIM: Phia Saban.

BIOGRAPHY

TRIGGER WARNING:violence, murder, and death. It was a tale found repeated often throughout history; a child of the wrong gender was born, and was thusly punished for it. For this, Isabelle, having the misfortune to be born into a minor branch of the royal House of Capet, was demeaned without pause for her short mortal life; by her father, by her ever sonless and bleeding mother, by her step-mother and all her vying male cousins.

She perfected the balance of being ever apologetic, ever sweet, ever so thankful; she haggled for the best prices on the jewels and fabrics gifted to her by suitors, and spoke to the bandits and witches without so much as a quickened heartbeat. Killing kin at their dinner tables and dark country roads and the birthing beds was hard work, but hardly anything to worry over.

A pious girl, she prayed in a small meadow every night. Granted, she was praying for all her tormentors to be skinned and boiled like little lambs, for God's righteous smiting, but prayer was prayer, was it not?

It seemed that something was listening, at least.

The dark shadow between the trees first attempted to take her maidenly blood with cooing and promises --- and, when that did not work, by force. When she would not stop biting and cursing it to hell, it took from her the blood of her throat, if only to make her quiet.

When she awoke, there was no hesitation. Violence had burned away all her fear and all her love, even if only for the night; she did as her thirst dictated and laid ruin to her house, as they had accused her of doing for all the years since her unfortunate birth.

In the years that followed, she travelled wherever she pleased, both kind and destructive in her constantly changing, forgotten whims. She found herself returning to France every few decades, where she had once been born.

It was during one of these visits, as she made the catacombs of Paris seem a castle in her quiet nobility, that she met a boy - or was he already a man grown? She can no longer recall, and no longer cares --- all are children compared to her.

Where was she? Ah... He was more a pet than a companion, really, but what a darling thing; ever her temporary coven's eager and, importantly, capable servant, she grew more than fond of Sebastien - and when the time came, it was her teeth that tore open his beautiful skin, and her blood that returned him to life. Such was her habit; Isabelle, saver of orphans, Isabelle, whose tears were more precious than an angel's, Isabelle, whose love waned and grew when she deemed it most effective.

The coven's destruction was imminent; to her, this was clear. She prepared with only a modicum of haste --- acting too quickly would alert the others of the danger, after all, and would disturb the results of her newest project --- and took anything of worth to estates outside of accursed France. Her body remained in the catacombs, smiling and sweet and appropriately frightened when holy fire rained upon them

She lingered, just enough to ensure her fledgling had survived the cleansing, before leaving once again, filling her years with art and jewels and a few killings of fellow immortals. Truthfully, she did forget poor Sebastien --- but was furious all the same to find him nowhere in France.

Since childhood, she worked hard to get all that she felt she deserved --- and nothing awoke her ire like being robbed of even the smallest piece of lace. She chased after his trail with a newfound hunger, ending up in Raven's Peak, where she now prowls for her missing servant.

EXTRAS

FILLING CONNECTION: yes - SIRE for SEBASTIEN BOUCHARD.INSPIRATIONS: N/A.

0 notes