#Hotel near Organ Pipe National Monument

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Best Places to Stay in Ajo Near Mexico Border

If you're planning a visit to southern Arizona, especially near the Mexico border, Ajo is a small but charming town worth a stop. Whether you're a road-tripper, border traveler, or exploring the Sonoran Desert, finding the right accommodation is key. This guide will help you discover the best places to stay in Ajo near the Mexico border, including cheap motels in Ajo AZ near the IGA store for those traveling on a budget.

Why Stay in Ajo, AZ?

Ajo is located just 40 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border at Lukeville, making it a popular resting spot for travelers heading into Mexico or returning. Surrounded by desert beauty and historical architecture, the town offers a peaceful stopover with convenient amenities like grocery stores, gas stations, and restaurants.

If you're looking for comfort, safety, and easy access to the border, there are several places to stay in Ajo near Mexico border that fit different travel styles and budgets.

Top Places to Stay in Ajo Near Mexico Border

1. Sonoran Desert Inn & Conference Center

Located in the heart of Ajo, this unique inn blends local culture with modern comfort. The former elementary school turned hotel features artist-designed rooms and an on-site garden. It’s ideal for travelers looking for a relaxing and culturally rich experience.

Distance to Mexico border: 40 miles

Bonus: Pet-friendly and artsy atmosphere

2. La Siesta Motel & RV Resort

One of the most popular cheap motels in Ajo AZ near the IGA store, La Siesta offers affordable, clean rooms and RV parking. Its convenient location on Highway 85 puts you within walking distance of grocery stores and eateries.

Budget-friendly rates

Less than a 5-minute walk from Ajo IGA store

Great for travelers on a tight schedule

3. Marine Motel

This budget option is a local favorite. Simple, no-frills rooms come with air conditioning and Wi-Fi. If you're just looking for a place to rest before continuing your journey, Marine Motel is a solid choice.

Affordable pricing

Easy access to Highway 85 and IGA store

Quiet and well-reviewed for overnight stays

Cheap Motels in Ajo AZ Near IGA Store

If convenience is your priority, look for cheap motels in Ajo AZ near the IGA store. Staying near the grocery store gives you quick access to food, supplies, and daily essentials. Most motels in this area are within walking distance of dining spots and gas stations, making them ideal for travelers passing through.

Tips for Booking Your Stay

Book Early in Peak Season: During winter months and holidays, rooms near the Mexico border fill up quickly.

Check for Amenities: Make sure your motel offers essentials like Wi-Fi, AC, and parking.

Ask About Border Travel Info: Some hotels provide local maps or guidance for travelers heading into Mexico.

Final Thoughts

Whether you're heading to Puerto Peñasco or exploring Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Ajo is a convenient and scenic stop. With several places to stay in Ajo near Mexico border, including cheap motels near the IGA store, you'll find comfort, convenience, and charm all in one desert town.

#Hotel near Organ Pipe National Monument#Cheap motels in Ajo AZ near IGA store#Places to stay in Ajo near Mexico border#Ajo Motel near Organ Pipe

0 notes

Text

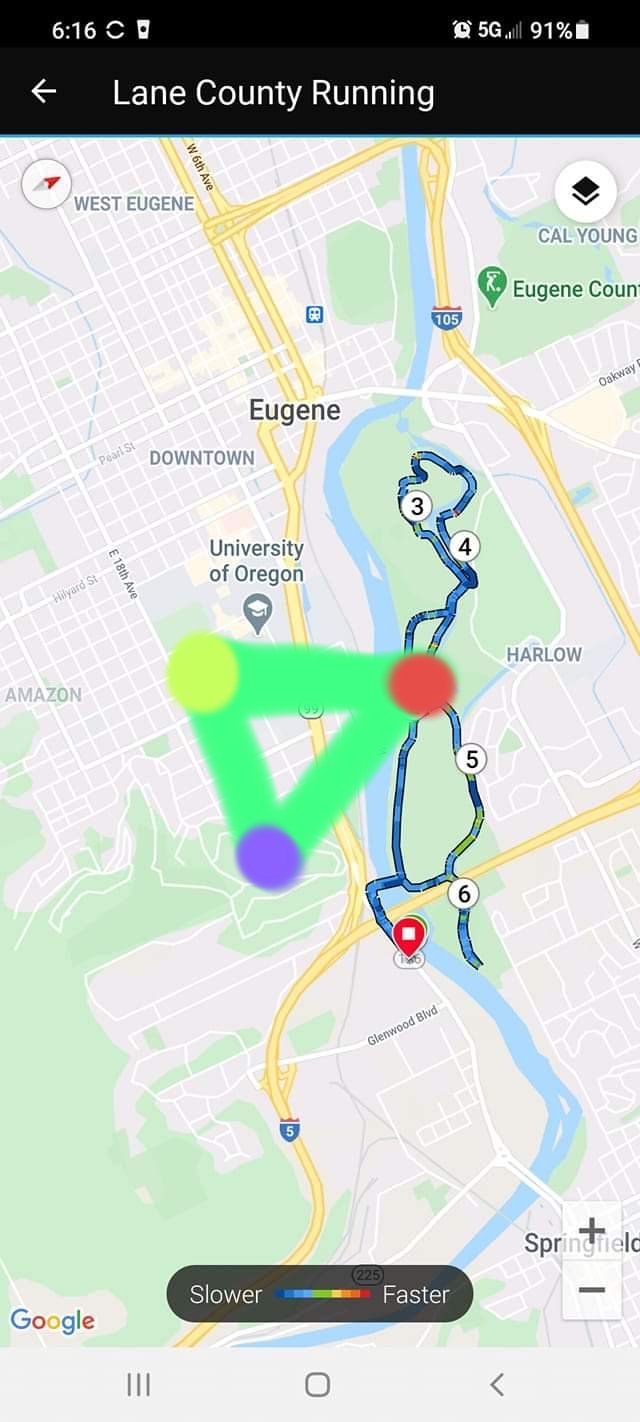

Pre's Triangle Our long journey to find a home has brought us to Eugene, Oregon. As though by fate, we landed smack in the middle of "Tracktown USA". As a distance runner who began his involvement in Cross Country, Track & Field, and Road Racing in the mid-1970's, I was familiar with the Bill Hayward, Bill Dellinger, and Bill Bowerman legacies. I also was a fan of the late Steve Prefontaine, sometimes referred to even now as "Eugene's favorite son". While closing the deal on our new home we found ourselves at a hotel directly across from the Willamette River, and just down the mountain from where Steve Prefontaine was killed in a car crash on May 30, 1975. At the time of his death, "Pre", as he was called by all who knew him; and heard shouted by the fans who used to chant his name during his many racing victories at Hayward Field; held every American Record from 2,000 through 10,000 meters. His former Junior National 5,000 meter record of 13:39.6 is still one of the fastest junior marks ever run. Pre was an Olympic finalist at the mere age of 23. He threw every gear he had into a race that he nearly won. Unfortunately, anything less than winning was unacceptable for the young upstart that was Steve Prefontaine. He faded to fourth on the home straight just yards from the finish losing the gold medal to Lasse Viren of Finland by just 1.7 seconds. Viren won both the 5,000 and 10,000 meter golds at both the 1972 Games in Munich and again in Montreal four years later. The Finn also finished fifth in the 1976 Olympic Marathon. The 1972 5,000 meters (same as 5 kilometers = 3.107 miles = 12 1/2 laps on a 400 meter track) was the race in which Prefontaine warded off several challenges before fading in those last steps over what was still a 4:04 final mile. Some have since said that Pre gave up, staggering the final yards and appearing to let up off the pace. I don't agree with that assessment. I believe that Pre made that race happen. Advised by his coach, Bill Bowermann, to not run from the front, as was Pre's want, because of the caliber of competition he was up against, Pre took a pedestrian pace from the first two thirds of the distance to an insanely world-class run. He went for the win and simply ran out of gas. Had Pre run safely for a medal, or waited just a while longer than he did, he likely would have walked away with at least the bronze. Leading into the final curve Pre held off one last charge by Viren before the Finn began to pull away on the home straight. Then Pre was passed for the silver by Mohammed Ghamoudi of Tunisia, and the bronze by a late surging Dave Bedford of Great Britain. Pre's finishing time of 13:27.6 was still less than five seconds off his own American record. The experience affected Pre greatly. He had a hard time coping with the loss, but eventually shook it off. On May 29, 1975 Pre participated in a meet at Hayward Field held to raise funds for the restoration of the ailing stadium. He even had a hand in organizing the meet. That was something Pre did regularly during his tenure at the University of Oregon, and the short time following his graduation. He decisively won the 5,000 in 13:23.5, defeating 72 Olympic Marathon champion Frank Shorter. That night Pre gave Shorter a ride to his place of lodging before returning to meet his girlfriend, Mary Marcyx, back at a post-meet party put on for participants and organizers of the Hayward restoration meet. He never made it to his destination. His death is still shrouded in mystery. The medical examiner's report concluded that Pre's blood alcohol was 0.14, above Oregon's legal limit of 0.10. Both Shorter, and Kenny Moore; another Olympic athlete; visited the scene the next day. Both contend there was no way that Pre was drunk. Both also contended that he knew the roads too well to have done anything reckless. One local witness claims that he heard the crash and, when coming to the scene to help Pre, saw another vehicle speed off. Others questioned local officials

motives, including the coroner's report, when a cherry picker was brought out to take photos of the scene. That just wasn't done, especially in the mid 1970's. Were officials trying to use Pre's fame to make an example of him? It is unlikely anyone will ever know what really happened at the site that is now called Pre's Rock, on Skyline Drive just yards from the corner of Skyline and Birch Lane in the wee hours of May 30, 1975. However, 46 years after his death, people still flock to the roadside monument and leave tributes; t-shirts, race bibs, medals, flowers, carvings, decorative stones, and other memorabilia. A local woman removes these gifts each month, discarding those that succumb to the elements, and donating others to museums. Still, more appear. From Skyline Drive, within sight of Pre's Rock, one can look down from the ridge and see the Willamette River, the large arched Interstate-5 Bridge, the Knickerbocker Bicycle Bridge, and Pre's Trail. The new torch on the very recently rebuilt Hayward Field is visible from Birch Lane as one loops just below Pre's Rock and heads North toward the center of town. Pre's trail was the result of his efforts to give the community a pedestrian trail that was much like those he saw while competing in Scandinavian countries. It is a series of woodchip trails that run over a two mile stretch of Alton Baker Park from below "The Pipe", about a half mile south of the I-5 bridge, to Day Island, past Autzen Stadium, to the north. If one were to cover every stretch of the woodchip paths, they would accumulate about 5 miles worth of exercise. It was a monumental effort to install and is well maintained. It is but one of the things that Pre gave back to the community. He did a lot for kids, the University, and to help athletes not be taken advantage of by the governing bodies of sport; giving the athletes more control over their own careers. Pre fought the corruption that was part of the old Amateur Athletic Union, reforming that body to become the Track Athletics Congress. Athletes were then able to establish trust funds to give them control over how prize money they won in competition was spent to help them compete, and still maintain their amateur status. Eventually, the TAC was dissolved and USA Track & Field was formed. Today, the sport still thrives. Even with the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic, events are in revival, and a new Hayward Field awaits another U.S. Olympic Trials, and, perhaps, a future Olympic Games. I have an area that I have dubbed "Pre's Triangle". I drew a line from Hayward Field to Pre's Rock, then out to the middle of Pre's Trail, and back to Hayward Field. It is an uncanny representation of the heart of Pre's legacy. I have now raced at Alton Baker Park within sight of Pre's Trail, as well as run quite a few training miles on the trail itself. Pre's spirit is still alive and well in Eugene.

Illus. - Yellow dot = Hayward Field location (Agate Street) ; Red dot = Pre's Trail (also marked in its entirety from a workout I did, located in Alton Baker Park); Purple dot = Pre's Rock (Skyline Drive near Birch Lane, not far from Hendricks Park).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

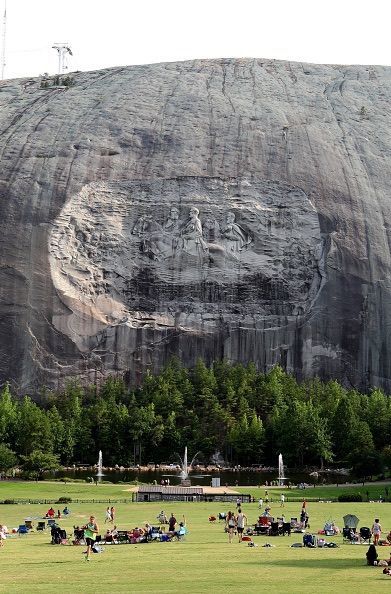

As investment pours in, a ‘new Stone Mountain Village’ aims to rise

The village’s Main Street and its proximity to Georgia’s most popular tourist attraction, as seen about five years ago. | Courtesy of Stone Mountain Downtown Development Authority

Brewers, developers, creatives, and other entrepreneurs call the village an up-and-coming, historic gem among metro Atlanta downtowns—its reputation be damned

The tour of what Jelani Linder and other enthused locals are calling the “new Stone Mountain Village” begins on a chilly Friday afternoon, at a local joint opened in 2018 called Stoned Pizza Kitchen, where every pun is intended. Linder, a Coldwell Banker Commercial Metro Brokers agent, is an unabashed ambassador for the village and a seasoned tour guide. He holds a masters degree in urban planning from the University of Georgia, serves as Stone Mountain’s Downtown Development Authority chair, and recently bought one of the city’s few new houses nearby with his wife, Shani. Before all of that, though, Linder grew up in another DeKalb County city, Decatur, when it was hardscrabble—back when his pals considered venturing into tony Oakhurst dangerous and gentrifying Kirkwood “a sin.”

Linder sees in Stone Mountain Village the next hip place, a refuge for Atlanta’s priced-out populace, and to prove it, we trek down East Mountain Street to—what else—the renovation project that’s becoming the city’s first big brewery.

“Once people can get over the perception, they get it,” Linder says of his city, en route. “It’s like a cult here, I’ll be honest with you, when people buy in. The enthusiasm, the excitement.”

Scheduled to open in March in a long-abandoned Pure filling station and auto shop, Outrun Brewing Company eschews the typical brewery motif of brick, reclaimed wood, and pipes; instead there’s pink neon, an arcade game the business is named for, and a “retro-futurism” vibe that feels like Stranger Things meets Miami Vice meets Milwaukee. The proprietors are two funny suds aficionados, Josh Miller and Ryan Silva, who met each other while running brewing operations at Decatur’s Three Taverns. It’s not long before they start echoing Linder’s boosterism, lending some credence to his “cult” quip.

Inside the forthcoming Outrun.

The former filling station’s patio affords mountain views.

Miller: “There’s so many new businesses coming into Stone Mountain. It’s potentially the next big area.”

Silva: “It’s not much different than Decatur 15 or 20 years ago. It could be another Decatur.”

Miller: “People always say, ‘You’re all the way out in Stone Mountain’—all the way out? Have you driven the 15-minute drive? I take Memorial [Drive] from the eastside, and there’s never traffic, no matter what time it is.”

Silva: “The reality is, a lot of people can’t afford to live in [Atlanta], and that’s fine. We’re trying to bridge the gap between the city and the severely underserved suburbs. We wanted to be in on it from the start, not the tail end. We want to be part of building the community up and the struggles that are part of that.”

(Whether the small city could handle an influx of new residents remains to be seen, however. More on that shortly.)

Miller: “There’s so much raw potential here. All it takes is a couple of people saying, ‘Hey, let’s try something.’ And I think that’s happening now. That’s how these towns get started. It’s going to be a whole new world.”

Linder, grinning near the entrance: “If you look at our street grid, it’s what Suwanee and all these new communities are trying to duplicate. We’ve had it for 100 years—now we’re just trying to fill in the gaps.”

Jelani and Shani Linder, outside a forthcoming barbecue restaurant from a Decatur chef.

The residue

Beyond the brewery’s garage doors, the future patio for Adirondack chairs, and a towering magnolia stands an amenity that no other historic downtown in metro Atlanta can claim: the world’s largest piece of exposed granite, like the pate of a balding giant. Stone Mountain Park—the rock and private adventure grounds—is Georgia’s most popular tourist attraction (4 million annual guests strong) and one of the most-visited in the entire Southeast. There’s a 3,200-acre wonderland of trails and recreational sites around the mountain, all free to anyone who might, say, grab a pizza or beer in the village and walk or bike six blocks to the park.

Getty Images

The park is also home to the country’s largest shrine to the Confederacy, the enormous bas-relief sculpture of three Civil War leaders carved into the northern face, and a long, sullied history of Ku Klux Klan rallies and racist gatherings, including KKK parades as recently as the 1980s and an alt-right rally in 2016. The monadnock’s climbable, moonscape beauty includes a carving of Gen. Robert E. Lee as tall as a nine-story building—recently decried as the “largest shrine to white supremacy in the history of the world”—and the boulevard ringing it all bears the general’s name. The park was promptly closed last year when white supremacists attempted to rally during Atlanta’s Super Bowl. And though a group called Georgia Tourism Product Development Team has stepped in to help counter the reputation with reality, as the AJC reported last year, social media has played no small part in wedding the majority-black area with images of chanting, Confederate-flag waving white nationalists.

Sure, the symbols harken back to important American history. But they represent a glaring contrast to what’s becoming a more charming, diversified, and progressive former railroad village just beyond the park gates, where a wave of private investment promises to turn dead storefronts into a more organic type of attraction.

“This growth was bound to happen,” says Dorian DeBarr, Decide DeKalb Development Authority’s interim president. “As investors educated themselves and took an opportunity to actually experience what the village has to offer, it was a no-brainer.”

Main Street scenes today.

More broadly, DeKalb saw a surge of capital investment in 2019 to more than $1.1 billion—eight times the previous year—and growth as an entertainment industry destination, with productions as disparate as Dolly Parton Presents, Watchmen, Bad Boys 3, and Jumanji: The Next Level filming nearby. The mountain itself, of course, was immortalized in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s most iconic speech, and this village of less than two square miles is where TV, music, and film superstar Donald Glover grew up.

So the contrast runs deep, like the granite. And for some, it stings.

“When you look at South DeKalb as a whole, it’s majority black, so you have to take that into consideration,” says Alan Peterson, the city’s Downtown Development Director with the DDA. “The monument, it’s state-owned. It’s history. It happened. There’s nothing we can do about it, and we’re just trying to move forward.”

The decline

Linder estimates that, as of a few years ago, between 60 and 70 percent of the early 20th century storefronts along Stone Mountain’s Main Street were vacant. Which makes a scathing Facebook review of the “ghost town” village, deposited on the city government’s page in 2016, no surprise:

“Only a few businesses remain and I can’t for the life of me understand how they are sustaining,” wrote one unimpressed patron. “The look on tourist faces when they visit downtown varies from shear surprise [sic], to disappointment and all-out disgust.”

The vacant, circa-1905 Stone Mountain Inn building is located down the block from most recent retail activity.

That description conflicts with the bustling hub the village used to be. During Reconstruction, the Main Street area sprang into a center of tourism and industry hinged on quarrying. Local granite was shipped across the world, used in Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, the Panama Canal, and in at least one building in almost every state in the U.S., including in the foundation of the Lincoln Memorial.

When the grounds around the mountain operated as a less-commercialized state park, the village was where tourists came for lunch, souvenirs, even a store that peddled butterflies, often riding a train that connected the two attractions. The state still owns the mountain but is leasing commercial operations for at least the next quarter-century to Norcross-based Herschend Family Entertainment, which owns or operates many other themed tourist hubs, such as Dollywood in Tennessee. The privatization deal began in 1988, and longtime locals say the village’s vibrancy soon changed, as the park’s main entrance was shifted to a U.S. Highway 78 exit, the village train ceased, and visitors began skirting the old town.

“I mean, they’re in business—nobody can blame [Herschend] for trying to keep the business in the park,” says Rory Webb, co-owner of Main Street bistro Stone Mountain Public House, who lives in a historic village house nearby. “But when they did all that, they virtually strangled the town. And I think a lot of the businesses weren’t willing or able to change with the times, to morph.”

Another struggle has been the misperception of rampant crime.

Business owners and longtime residents say two or three police officers from the city’s small department are seen patrolling the city’s 1.7 miles at most times, lending a sense of quietude—a bubble, even. Stone Mountain Police Department statistics show violent crime rates in 2019 at four per every 1,000 residents—or about 1/6 of the national average. An average of 21 property crimes, however, were reported per month last year, so it’s relatively safe but not exactly Mayberry.

“The worst thing is, a lot of people hear ‘Stone Mountain,’ and they think of unincorporated Stone Mountain,” says Webb. “You turn the news on, and there’s a stabbing or shooting in Stone Mountain, but you look, and it’s the DeKalb police, not inside the village.”

“It’s frustrating,” the DDA’s Peterson concurs. “We’re a small city, and our police force does a great job.”

The Main Street DIY crafts hub Stillwell’s Emporium, decorated for the village’s Mardi Gras parade in February.

Back on the walking tour, the Linders lead the way into a CBD retailer that opened next to the new pizza parlor in January, The Rose & Hemp. Behind the counter, founder Scott Koester says he and his wife, with a baby on the way, traded a 1,250-square-foot East Lake bungalow for a house they bought more than three times that size outside the village’s limits. He plans to live there for decades.

Koester was easily sold on the business location, he says, after parking across the street one day—in a lot where a free, open-container Friday music series, Tunes by the Tracks, will happen again this spring—and taking one look at Main Street’s bones.

“I can’t speak to the past, because I don’t know, I haven’t been here,” says Koester. “But it seems like a lot of people are coming together, to work together and make this a place people want to come.”

Directly above the shop, Lauren Godfrey and Ebonee Thompson, two friends and tech-company coworkers, are putting the finishing touches on the city’s first large coworking space, C3 Village, a sort of warmer WeWork with endearingly creaky floors and a lounge designed to resemble a Friends set. Like the brewers, CBD entrepreneur, and many others, they spoke of building a village of business allies and not competitors, each boat rising with a tide.

“Look, I’m a black girl from Florida, she’s a white girl from Georgia, and I think that it speaks to the story that people from completely different backgrounds can come together and create something so magical, something so passionate,” says Thompson, whose background in tourism has also landed her a deal to run the city’s new social media campaign. “That speaks volumes to what this community can do.”

Thompson and Godfrey, in the circa-1940 space they’ve renovated themselves into a coworking hub.

The upswing

As part of the city’s refined pitch to more investors, Peterson says the DDA is in the process of tabulating how much private investment—hundreds of thousands, at least—Stone Mountain has recently seen.

In January, the city inked a $155,000 contract with Atlanta architecture and engineering firm Pond to create a new downtown masterplan. Expected to be ready by August, the plan will aim to boost village esthetics and channel area visitors in from main arteries (by way of enhanced signage, as a starting point). Changes could also include additional bike lanes and green space meant to build off cyclist traffic that the popular PATH trail brings. A current city motto—“Atlanta’s Mountain Town”—is destined for the Dumpster, Peterson says.

Beyond the buildouts for forthcoming businesses, the makings of a buzzy, urban-style place are already here, headed by a diverse set of proprietors: a bike shop, arts center, theater, makers studio, antique shops, health store, new coffee house Gilly Brew Bar, event center and music studio 5380 Studios, a pie shop, and longstanding eateries like Public House, Sweet Potato Cafe (in a funky bungalow off Main Street), and the stalwart Wells Cargo Cafe.

Gilly’s coffee house occupies the 1834 former home of Stone Mountain’s first mayor, where both Union and Confederate casualties were hospitalized during the Civil War. A new restaurant is also planned.

“I mean, Stone Mountain is one of the largest attractions in the Southeast,” says Gilly barista Ivan Solis. “It’s kind of crazy how many people go there, but don’t come here. It’s kind of weird.”

Around the corner from the brewery in a circa-1900 brick building, however, could be the most-hyped new attraction on the walking tour: 13th Colony BBQ, a venture by Stone Mountain native Jonathan Hartnett of Decatur’s Las Brasas. That’s expected to open in April, on the corner opposite Stoned Pizza Kitchen, lending another commercial jolt to the village’s nucleic intersection.

“People love to see old historic buildings from the early 1900s repurposed,” says David Downs, a Realtor with Keller Knapp Realty, who fell for the village during group cycling rides from Decatur—and who’s bought and renovated three Main Street buildings in recent years. “You can’t build history.”

Housing outlook

As a tangerine sunset flares over the pines, the walking tour concludes at a development called Hearthstone Park that could lend a glimpse at Stone Mountain Village’s residential future—where the Linders both own a home and, as real estate agents, are actively selling others.

Jelani, who’s been a village resident and homeowner since 2006, says Hearthstone marks the city’s first new housing development in nearly 20 years. Thirty-four standalone houses are planned around a central park, each with three bedrooms and mountain views. A starting price of $285,000 buys 1,500 square feet and change, while the $350,000 range gets a finished basement and 2,400 square feet.

“This is a half-million dollar product intown, at least,” Jelani notes in the model unit’s living room. “It’s something for people getting pushed out, or empty-nesters.”

For existing housing stock, Neighborhood Scout pegs the median Stone Mountain home value at just $127,724, with a majority built between 1970 and 1999. Per recent sales records, the low $200,000s buys a livable three-bedroom, midcentury bungalow within a few blocks of the village.

But the renovated classics near Main Street are harder to come by, often trading by word of mouth before listing. “When older homes do come on the market,” says Shani, “they go like that—snap!”

Census estimates show the city’s population has inched up by less than 500 people since 2010. And Jelani says infill opportunities in city limits are limited. So one can’t help but wonder, should the droves come seeking relatively affordable housing in a unique, walkable, outdoorsy setting—amidst a metro expected to ballon with 3 million more people by 2050—where they all might fit.

But that’s a matter for another, more sober day.

It being Friday night, the Public House—the village’s de facto Cheers—comes alive with clinking glasses, ragtime music, and karaoke crowds. In the back, huddled around a booth, Webb the co-owner describes how the village retains an overtly friendly, come-on-over southernness without the yesteryear stigma. He points to a crowd that’s diverse—and by all indications, defiantly proud of it.

“You either fall in love with the village, or you don’t,” says Webb. “And if you do, you got to live here. It’s the best hidden gem in Georgia.”

From the mountain’s summit, with downtown and Midtown Atlanta beyond, and the village below.

source https://atlanta.curbed.com/2020/2/28/21128454/stone-mountain-village-park-atlanta-restaurants-brewery-main-street

0 notes

Link

In case you need to remind that the relationship between France and Germany heaven is always intimate, go to Thionville in the Grand Est Region.

The town, near the Luxembourg border, has been under intense debate since its inception and has witnessed six sieges in just 500 years. The more recent conflicts between the nations have left the landscape littered with fortresses, some built when Lorraine was annexed by Germany and others part of the ambitious French Maginot Line. Thionville was loaded into the heavy industry after the war, and although iron mines and steel plants were deposited in the past, their memories were kept in museums and gardens. Discover the best things to do in Thionville.

[toc]

1. Ouvrage Hackenberg

If you want somewhere to start a tour of the Maginot Line, turn it into a rural fortress east of Thionville. The Ouvrage Hackenburg never faced a frontal assault, so the concrete shell and labyrinth of underground tunnels are still intact.

One of the blocks here has been restored to working order, and you’ll take the elevator to the bowels of the fortress and ride on the electric train that serviced these tunnels.

The tour is exhaustive, demonstrating the working gun turrets and explaining every technical detail you could want to know, including how the tunnels were cleverly designed to extract smoke and gas.

2. Tour aux Puces

The oldest monument in the city is the former site of a castle built by the Earl of Luxembourg. The Tour aux Puces (Tower of the Fleas) would have been raised around the 11th or 12th centuries and was modified right up to the 16th century.

Its current 14-sided design is from the time of the Spanish occupation when it was integrated into a sequence of defenses on the Moselle River. The oldest walls are on the northeastern side where you can still see the stonework from the 1000s.

3. Musée de la Tour aux Puces

To get a handle on Thionville’s complex history step inside the tower where there’s a museum with a large hoard of artifacts to inspect. You’ll get a chronological summary of the main episodes in the town’s past, from prehistory up to the Renaissance.

The appeal has been updated with modern systems and helpful explanations that come with its screen. You’ll see Neolithic hand axes, Gallo-Roman sculptures, Merovingian jewelry and beautifully carved tombstones from the late middle ages.

4. Fort de Guentrange

Here’s another sight that reveals Thionville’s complex heritage. It’s a formidable construction and was actually one of a whole program of fortifications between here and Metz.

Despite the enormous amount spent on this fortress, it never saw any action and escaped the damage during World War II attacks when it stored weapons like V-bombs. -first.

There are regular 90-minute tours of this enormous installation that could hold a garrison of 2,000 men and was fitted with eight long-range guns and early telephone communications.

5. Mines de Fer de Neufchef

The northwestern side of Lorraine is pocked with iron mines that were sunk two hundred years ago but closed down after the war. Two of these have been kept as museums to educate the next generation about the region’s bygone iron and steel industry.

The local one is minutes west of Thionville at Neufchef and has maintained 1.5 kilometers of underground galleries.

You’ll be talked through it all by a former miner, before entering several well laid-out rooms explaining the day-to-day life of a miner and the geology that made the industry possible.

6. Zoo d’Amnéville

In 15 minutes, you'll be at the largest zoo in eastern France, with 1,500 animals from 360 species. The Zoo d’Amnéville stands out for its gorillas and orangutans and is spread over 18 hectares of meadow and woodland.

The Plaine Africaine is a highpoint, with giraffes, zebras, ostriches, and antelopes coexisting in a three-hectare enclosure. Attendance at the park has skyrocketed over the past few years after the zoo revealed Tiger World programs, using domesticated tigers.

These are 45-minute spectacles with a dozen big cats, but they’re a controversial addition and have seen the zoo downgraded to a temporary member of the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

7. Sights around Thionville

Thionville is a small town, so you can make a tour of Thionville in a few hours. As with the attractions and attractions on this list, there are a few small landmarks to search for. One is the Autel de la Patrie (Altar of the Fatherland), a highly rare memorial to the Revolution, erected in 1796 and featuring the Masonic symbol of the Eye of Providence.

The town’s streets are edged by some lovely old houses from between the 1400s and 1700s, as well as more extravagant hôtels particuliers. See the Hôtel de Créhange-Pittange from the 18th century and the town hall, which is, in fact, a converted convent dating to 1641.

8. Château de Volkrange

A little further from the western suburb of Thionville, is a delicate 1200-year-old castle embedded in a 30-hectare park. In the spring and summer, the hotel comes to life with workshops for ancestral crafts and activities such as cutting stones, stained glass, and manuscript lighting.

The property itself suffered serious damage in the Thirty Years’ War, then to be restored in the 18th century. On the grounds, you can also poke around outbuildings like the beautiful 18th-century dovecote and the stables.

9. Jardin des Traces

Boarding Moselle at Uckange is an extraordinary garden advertised as Islamic Le Jardin de l'Impossible. You probably know why when you see it because the attraction lies in the darkness of a blast furnace on an old industrial estate.

And although this isn’t the ideal location for a garden to thrive in, it’s a perfect statement of the Moselle department’s industrial past and what it wants to be in the future.

The garden has three sections, each dealing with a different aspect of the iron industry, from the elements that came together to make it thrive, to the people who traveled from all over Europe to work here.

And finally, there’s a statement about the region in the future and its commitment to renewable energy.

10. Église Saint-Maximin

Thionville’s solid-looking church was built in the French Classical style in the middle of the 18th century. The French army really had a hand in their design when they wanted the two towers above the western portal to be watchful positions.

But it has an interior that really shines, especially the high altar and the Tripitaka. The latter is a true historical document, along with the organ styles of France and North Germany, as it was modified during the 19th century when Thionville was both French and German.

This marvelous instrument has 4,500 pipes played with three 56-note keyboards and a 30-note set of pedals.

More ideals for you: Top 10 things to do in Teramo

From : https://wikitopx.com/travel/top-10-things-to-do-in-thionville-709965.html

0 notes

Text

On California’s Lost Coast: Sea Lions, Surf and Squiggly Roads

On a deserted beach in Northern California, I mistook a sea lion for driftwood. The Lost Coast is deceiving that way. Wild things appear tame and tame things, like the paved road my family and I took to get here, wild.

In June, seeking immersion in nature, we visited the Lost Coast, the largely roadless shore between the indiscernibly tiny town of Rockport and the Victorian charmer Ferndale, about 100 miles apart by inland roads. Here in Humboldt County, California reaches its westernmost point near a junction of three seismically active tectonic plates. The King Range mountains plunge into the sea, deterring road-builders from continuing State Route 1 along the ocean. Breaking waves strew driftwood along beaches reached by hiking trails that require consulting a tide chart. It’s cold and foggy, even in summer, and just rough enough to keep all but the most intrepid day-trippers away.

“No one comes here without intending to come here,” said Verna Kaai, the manager of the Tides Inn, a homey base in Shelter Cove, the oceanfront gateway to the Lost Coast, when I booked a room for three days amid a weeklong road trip. “We’re only about 20 miles from the highway,” she said of the squiggly access road that connects the town to the nearest thoroughfare, “but it will take you up to an hour to travel.”

That sounded like our speed. And while the coast wasn’t lost to the Native Americans, loggers and cannabis growers who have left their mark here, it appealed to us in another escapist sense: little connectivity. Ms. Kaai assured me I wouldn’t have cellular service, though the hotel had very slow Wi-Fi. In this screen-centric age, a few scenic and relatively unwired places remain in the United States, such as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in southern Arizona and parts of the Adirondack Mountains in New York. But this slice of California’s coast — only some 225 miles north of San Francisco — seems, well, lost in plain sight.

A harrowing drive

Long before it went missing, the area was populated by Native American Sinkyone and Mattole people, and later, lumberjacks and harvesters of tanoak bark, used to tan leather. The Gold Rush in the mid-19th century brought more settlers, and logging intensified in the race to rebuild the city after the San Francisco earthquake in 1906. Churning seas tended to wash out piers, which killed most attempts to fish commercially in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1970, after the timber industry had depleted much of the area, and depopulation drew pot growers, the 68,000-acre King Range National Conservation Area, which protects 35 miles of coast and mountains up to 4,088 feet, became the country’s first National Conservation Area.

Now, visitors come to the Lost Coast to hike, fish, beachcomb, bird-watch and scan the ocean for migrating whales in the offshore marine preserve (Ms. Kaai recommended visiting on a weekend, when Shelter Cove’s few restaurants are open). Others come to backpack along the famous Lost Coast Trail-North, a nearly 25-mile beach trek that generally takes three days, requires a permit (free, with a $6 reservation fee) and is subject to tides that periodically make portions impassable.

Like the hiking here, driving to reach the Lost Coast requires a degree of fortitude. The builders of California’s Highway 1, which skirts the Pacific from Orange County more than 600 miles north, gave up the shore plan at the King Range, a topographic accordion we glimpsed in hazy fog and spray before veering inland. It ends at Leggett, about 15 miles from the ocean, funneling drivers onto U.S. 101, which continues north through southern Humboldt County before rejoining the coast near Eureka.

From the U.S. 101 exit at Garberville, 23 miles from Leggett, the route to Shelter Cove turned westward and challenging. For the next 50 minutes of concentrated driving, my husband, Dave, worked hard to maintain 35 miles per hour winding up mountain ridges and through dense fir forests, and downshifting at the continuous switchbacks to avoid overheating the brakes. Past the town limit sign for Shelter Cove, population 809, I finally relinquished my clutch on the Jeep door handle at the ocean panorama of surf-bashed rock islands and mountain-backed beaches.

Shelter Cove, at last

On the southern end of the Lost Coast Trail-North, Shelter Cove is scattered across a largely treeless peninsula that protects the town’s namesake, a south-facing cove. A general store on the access road deals groceries and hardware in the absence of any commercial main street in town. Modest houses dot the shore, leaving plenty of gaps for places with names like Seal Rock and Abalone Point, and views to the sea from most vantage points, including a campground and a lightly used nine-hole golf course. The closest thing to a town square is the community center, which, when we visited, was holding a group garage sale near the landing strip that parallels the coast.

Between the runway and the sea, the location of the eight-room Tides Inn — a three-story cross between a motel and a McMansion that is perched above a cove and hugged by rocky arms — exceeded our expectations. Our suite was thoughtfully furnished with nautical décor in the bedroom, a kitchenette nook with a mini-refrigerator and microwave and a high-top dining table. But the views made you forget about anything indoors. From our third-floor balcony, we could hear sea lions barking each morning and watch sunsets late each evening.

While it remains a destination for lovers of isolation, Shelter Cove has added a few tourist-friendly essentials in the past year, including a brewpub and a Venezuelan restaurant, Mi Mochima. On our first night, we followed the music across a ball field and skirted the unfenced landing strip to find Gyppo Ale Mill, a microbrewery, which takes its name from independent timber crews who came to Northern California to fell big trees (some logging remains, though environmental activists are fighting to preserve one of the region’s remaining old-growth Douglas fir stands, known as Rainbow Ridge). On this Friday night, the local band Planet 4 played funky tributes to Dr. John, who had recently died, and children ran circles around a cornhole-playing field.

Like us, the Gyppo Ale Mill’s co-owner Julie Peacock took one of the dramatic drives to the Lost Coast region and immediately fell in love with it. In 2001, she and her husband, Josh Monschke, whose family has roots in Humboldt County logging, left ski resort jobs in Utah to move to the area to farm marijuana, and he continues to run a nursery. They opened Gyppo last spring and call it “California’s most remote brewery,” because, said Ms. Peacock, “I haven’t found one more remote.”

We felt we’d earned an I.P.A. or two, after the harrowing drive in, but learned that’s not an excuse used by residents.

“Locals think nothing of driving that road to town,” said Katie Wallace-Schmidt, the manager of Gyppo as she delivered falafel burgers and lamb sausage to our table. “In L.A., I could easily be on the highway for 50 minutes to go 10 miles. I’d much rather be here.”

A dose of wilderness therapy

Given the weather, which generally peaks in the 60s in summer, we didn’t consider Shelter Cove a swim destination, though we found hardy bathers dipping into the shallows at Cove Beach on Saturday morning. By afternoon, a dozen SUVs and pickup trucks were parked on the popular beach, a rare safe place to swim along the Lost Coast, which is known for its rip currents and shore-breaking waves.

If not a traditional beach-lovers’ shore, the Lost Coast is ideal for losing time climbing over craggy rocks and inspecting tide pools. Between hikes in the conservation area, we scrambled around the peninsula’s rough edges, watching whistling oystercatchers, turkey vultures with their wings spread to dry in the sun, and sleepy harbor seals, some of them still pale in their juvenile coats (a notice posted in the Tides Inn window warned visitors from getting close to the pups, which are often alone and mistaken for orphaned while their parents, who may abandon their babies if in the presence of humans, are out fishing).

The Bureau of Land Management, which oversees the King Range preserve, allows 60 overnight backpackers per day to depart on the Lost Coast Trail-North between May 15 and Sept. 15 (30 people per day are permitted the rest of the year, when worsening weather notoriously alters and sometimes washes out parts of the trail). Day hikers do not need a permit. On our visit, the Shelter Cove trailhead parking lot was full, with more than two dozen cars, and a nearby street was lined with the overflow, indicating the numbers of hikers somewhere along the coast. Still, we felt we had the trail to ourselves Saturday morning, along with a black bear, possibly, based on the fresh scat we encountered.

From the Shelter Cove trailhead at Black Sands Beach, the going was slow on spongy black sand and tumbled sandstones that were hard to grip as our boots sank inches with each step. The slow pace that beach hiking enforced worked as wilderness therapy. We combed the high-tide line, finding patterned sea urchin shells, sun-bleached sea stars, driftwood sanded by waves and the occasional crab trap. Near the breaking surf, we nearly bumped into a juvenile sea lion we mistook for a log. We took breaks atop 20-foot high boulders that appeared to have tumbled from a mountain peak with an evident rock slide on its oceanfront face (the offshore Mendocino Triple Junction sets off frequent tremblers in an area where the three tectonic plates meet). Massive timbers made sturdy bridges to cross mountain streams that run down the slopes and cut through the sand on their way to the sea.

Venezuelan fare, blind curves and a tiny lighthouse

That night we gorged at Mi Mochima, a sunny new Venezuelan spot with its own boomerang story. The married owners, Blu Graham and Maria Graham Diaz, met in Venezuela where he was a scuba-diving guide. In 2011, after moving back to the coast where he grew up, Mr. Graham opened the neighboring Lost Coast Adventure Tours, which offers guided backpacking trips on the trail. The ocean-view A-frame restaurant, where Ms. Diaz is the chef, is designed to balance out their seasonal business, offering mini fish empanadas, garlic-sautéed prawns and a hearty shredded beef stew known as pabellón criollo. Our waitress, the couple’s adult daughter, Indiana Graham, explained that the coastal town of Mochima, Venezuela, and Shelter Cove are only distant in a geographic sense.

“They both are all about the ocean,” she said.

Getting to the northern trailhead at the Mattole River the following day was the most extreme of our adventure drives. Our innkeepers recommended a paved route largely outside of the conservation area that still turned out to be a hair-raising, one-hour, 40-minute errand on narrow roads that occasionally pinched to one lane, often, it seemed, just as we reached a blind curve (Lost Coast Adventure Tours, also offers shuttle service to the trailhead in 11-passenger vans).

A series of determined roads ascended pine-dense hillsides, undulated over mountain passes of wildflower meadows and tunneled through trees, only to descend and make the climb all over again. The few towns indicated on the map were easy to miss, though the general store in Honeydew, a blink of a town where a few intriguing back roads intersect, was thronged with dirt bikers on a group drive. We passed through sleepy Petrolia, site of the first oil well drilled in California, and took the relatively flat Lighthouse Road that follows the tail end of the Mattole River to reach the Lost Coast Trail at its top end.

In contrast to the pine forests around the southern trailhead at Shelter Cove, grassy woodlands border the northern gateway. Desert wildflowers, including globe-shaped yellow sand verbena, daisylike purple fleabane and violet lupine, bloomed in the dunes. A deer grazed a hillside and sea lions on offshore rocks barked at our approach. At just over three miles in, a colony of elephant seals dozed below the squat, white Punta Gorda Lighthouse, a remote, long-decommissioned beacon anchoring a grassy hillside above the shore.

Leaving the Lost Coast northbound saves one of the best adventure drives for last when, past Petrolia, two-lane Mattole Road links to the coast again and follows an undeveloped stretch. Bushy wild radish plants crowded the road as it climbed inland and, 90 minutes later, abruptly disgorged us in Ferndale, a manicured Victorian-era Mayberry. There, a ukulele ensemble was jamming in a bank parking lot, a comparatively found spot — with cellular service restored — at the border of the lost wilds.

Elaine Glusac is a frequent contributor to the Travel section.

52 PLACES AND MUCH, MUCH MORE Follow our 52 Places traveler, Sebastian Modak, on Instagram as he travels the world, and discover more Travel coverage by following us on Twitter and Facebook. And sign up for our Travel Dispatch newsletter: Each week you’ll receive tips on traveling smarter, stories on hot destinations and access to photos from all over the world.

Sahred From Source link Travel

from WordPress http://bit.ly/30KSLQV via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Tower-ing Fiction #9: Glass Tower, The Towering Inferno (1974)

by Shawn Gilmore

The Towering Inferno (dir. John Guillerman, 1974) is one of the Irwin Allen-produced disaster epics helped establish the modern blockbuster in terms of scale, stakes, and narrative setup. Without it, we wouldn’t have later films like Die Hard (dir. John McTiernan, 1988) or even Skyscraper (dir. Rawson Marshall Thurber, 2018), as previously covered in the Tower-ing Fiction series. And at its heart is the Glass Tower, a modern skyscraper, billed as “the tallest building in the world,” which of course will become the titular towering inferno, which will erupt over “a night of blazing suspense,” as promotional materials don’t attempt to hide.

The plot of the film is fairly thin—architect Doug Roberts (Paul Newman) has returned to San Francisco for the dedication of the building he designed the builder, James Duncan (William Holden); an electrical fire breaks out on the 81st floor, likely because Duncan’s son-in-law cut corners; during the dedication ceremony itself, a full fire erupts, and fire chief Michael O’Hallorhan (Steve McQueen) is called in to try to rescue those trapped inside, many from the 135th floor Promenade Room, roof, offices, elevators, etc. The star-studded cast is populated by actors playing types (as named on the poster): Faye Dunaway as the Girlfriend, Fred Astaire as the Con-Man, Susan Blakely as the Wife, Richard Chamberlain as the Son-in-Law, Jennifer Jones as the Widow, OJ Simpson as the Security Man, Robert Vaughn as the Senator, and Robert Wagner as the Publicity Man. There is much fire, and yelling, and a few tests of wills, but the film focuses on moment-by-moment solutions to immediate danger—how will a cluster of our characters make it through the peril in front of them, and can they trust one another to do so? In the end, much of the fire is doused by blowing up roof-top water tanks, with O’Hallorhan’s ingenuity saving nearly all of those involved.

The Glass Tower

The film opens with a nearly five-minute helicopter trip up the coast, past the Golden Gate Bridge, and into San Francisco, so that architect Doug Roberts (Newman) can see his completed design:

This opening concludes with a skyline shot dominated by The Glass Tower (center) with its base firmly on Market Street and a second, flat-roofed rectangular tower to its northwest, the Peerless Building, which will come into the plot much later in the film. Both are composited (pre-CGI) into the San Francisco skyline

The Glass Tower is presented as a 138 story, 1,652’ tower (which would make it the world’s tallest at the time), clad in amber-tinted walls of glass, with an angular façade, located at 655 Market Street (the real site of the historic Plaza Hotel), at the base of the Financial District. For reference, just between them, within a block of the fictional Peerless Building, is the real-world 38 story, 528’ McKesson Plaza (seen to the right and about half the height of Peerless tower, above).

The Duncan Corporation’s motto is “We Build for Life” and the Glass Tower gives the impression of gilded stability, presented as monumental and a beacon in the night as the lights are fully lit:

The look of the tower, particularly its base, is modelled on the Hyatt Regency San Francisco (which had just opened in 1973), just a few blocks up on Market, and which served as a shooting location for the lobby of the Glass Tower, and whose distinctive pill-shaped elevators appear directly in the film, including in a climactic rescue scene near the end.

The design of the building, both exterior (above) and interior, emphasizes angularity:

This is of course set up for the titular inferno, so that the viewer can track the various events.

In the multi-stage climax, a breeches buoy line is rigged to the lower roof of the nearby Peerless Building, allowing people to shift across:

While an elevator detaches from its track, forcing O’Hallorhan (McQueen) to cut it loose and guide a helicopter to lower it to street level:

Finally, water tanks near the roof are detonated, drenching the remaining stars:

And visually establishing the look that would later show up in films like Die Hard:

Before quenching the external flames as well:

From Prose to Screen

The Towering Inferno was adapted from two fairly similar thrillers, The Tower (1973) by Richard Martin Stern and The Glass Inferno (1974) by Thomas N. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson. The Tower focuses on the grand opening of the World Tower Building in Lower Manhattan, built near the World Trade Center Towers (which had been completed in 1970 and 1971), and is billed as even taller, at 125 stories and 1,527’; the plot hinges on shortcuts in the electrical systems, a disgruntled sheet-metal worker with a bomb, which coupled sets off a fire that traps the important guests in the 125th floor Tower Room, some of whom are saved by a breeches buoy line secured to the nearby (and lower) North Tower of the World Trade Center. The Glass Inferno concerns itself with the “Glass House,” or more properly the National Curtainwall Building, which is some 66 stories tall an located in an unnamed American city; again, corners were cut in the construction of the tower, there are disgruntled employees, and a fire breaks out, and in this iteration, those remaining are saved from the penthouse Promenade Room by a combination of helicopter rescue and exploding water tanks to put out most of the fire.

Warner Brothers bought the rights to The Tower and 20th Century Fox snagged The Glass Inferno, putting two similar films in to production. Allen convinced the two studios to jointly produce his film, splitting revenues, with domestic proceeds going to Fox and international to Warner Brothers. These parallel novels were then merged by Stirling Silliphant (who also wrote scripts for In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison, 1967) and The Poseidon Adventure) in to one synthetic story, and copies of both novels were rolled out with film-specific branding.

The two novels make their respective towers central characters.

The Tower opens with a set of diegetic descriptions of the World Tower:

It is the world’s tallest structure, and the most modern, an enduring tribute to man’s ingenuity, skill, and vision. It is a triumph of imagination. —GROVER FRAZEE at the World Tower dedication ceremonies. A monument to Mammon, product of man’s insatiable ego, an affront to the gods. That so much treasure should have been poured into the construction of this — this monstrosity while poverty, yes, and even hunger still stalk the land, is an abomination! There will be inevitable Divine retribution! —THE REVEREND JOE WILLIE THOMAS in a press interview.

Which is then followed by an extended prologue, moving from the construction to the tower as a living thing:

For one hundred and twenty-five floors, from street level to Tower Room, the building rose tall and clean and shining. […] By comparison with the twin masses of the nearby Trade Center, the building appeared slim, almost delicate, a thing of fragile-seeming grace and beauty. But eight subbasements beneath the street level its roots were anchored deep in the bedrock of the island; and its core and external skeleton, cunningly contrived, had the strength of laminated spring steel. […] Through its telephone, radio, and television systems operating at ground level, broadcasting through the atmosphere or via satellite, its sphere of communication was, quite simply, the earth. It could even communicate with itself, floor to floor, subbasement to gleaming tower.

[…] As the structure grew, its arteries, veins, nerves, and muscles were woven into the whole: miles of wiring, piping, utility ducting; cables and conduits; heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning ducts, intakes, and outlets—and always, always the monitoring systems and devices to oversee and control the building’s internal environment, its health, its life. Sensors to relay information on temperature, humidity, air flow and content; computers to assimilate the data, evaluate them, issue essential instructions for continuation or change. […] The building breathed, manipulated its internal systems, slept only as the human body sleeps: heart, lungs, cleansing organs functioning on automatic control, encephalic waves pulsing ceaselessly.

[…] Men had envisioned it, conceived it, and constructed it, sometimes almost lovingly, sometimes with near hatred, because, like all great projects, the building had early on developed a character of its own, and no man intimately associated with it could escape involvement. There is, it seems, a feedback. What man creates with his hands or his mind becomes a part of himself. And there, on this morning, the building stood, its uppermost tip catching the first rays of sunrise while the rest of the city still slept in shadow; and the thousands of men who had had a part in the building’s design and construction were going to remember this day forever.

Later, in chapter 12, as the inferno rages, a character reflects that “the great shining World Tower she had visited so often during the years of its construction […] was crippled now, a helpless giant” and the people on the street gazing upon the tower, “like ghouls, spectators at a public execution lusting for more blood, more terror.” In the next chapter, an omniscient narrator characterizes the building a cursed:

For some from the start it was one of those jobs you writhed in dreams about and awakened sweating. The sheer magnitude of the World Tower was frightening, but it was more, far more than that. The building taking shape seemed to develop a personality of its own, and that personality was malign. On a cold fall day a freak wind whipped through the huge empty space where the plaza would be, picked up a loose piece of corrugation, and scaled it as a boy might scale a flattened tin can. A workman named Bowers saw it coming, tried too late to duck, and was almost but not quite decapitated. The front tire of a partially off-loaded truck standing perfectly still suddenly blew out with sufficient force to shift the untied load of pipe, burying three men in a tangle of assorted fractures. On another cold fall day a fire started in a subbasement, spread through piled lumber, and trapped two men in a tunnel. They were rescued alive—just. Paul Simmons was standing outside the building, talking with one of his foremen, when Pete Janowski walked off the steel at floor 65. The Doppler effect accentuated the man’s screams until they ended abruptly with a sickening thunk that Paul, not ten feet away, would never forget.

And finally, near the end of the novel, in chapter 30, when speculating on motivations of Connor, the bomber, we learn that:

“[…] the World Tower building was the last real job he had. He was fired. There’s a connection, but maybe you have to be loony to see it. I don’t know. All I know are the facts.” In a vague kind of way it made sense. All three men felt it. The Establishment had killed Connors’s wife, hadn’t it? The World Tower building was the brand-new shining symbol of the Establishment, wasn’t it? Well?

So, the World Tower, man’s creation (and mirror of himself) is both malign and the Man, the inferno of the novel a kind of public execution, spurred on by one man’s rage at its symbolic stakes.

The Glass Inferno (1974) opens with teasing advertising copy:

The snow that began falling on Thanksgiving Eve added an extra magic to the spectacular new sixty-six-story high rise known as the Glass House. It dominated the city skyline: the latest triumph of modern architecture and engineering. But unnoticed, deep within it, a tiny spark grew until it became an inferno that changed the lives of the hundreds who worked or lived in the building—as well as the architect who designed it, the contractors who built it, the newsman who first warned of its dangers, and the firemen compelled to risk their lives because of another’s man’s greed and misjudgment. A gripping story of fire in a modem high rise, The Glass Inferno is an unforgettable novel of men and women caught in crisis, their heroism and cowardice, their unforgivable weaknesses and surprising strengths. As much fact as fiction, this is the revealing account of a holocaust that no fire department anywhere is equipped to fight. A novel, as uncomfortably close to the city cliff dweller as tomorrow’s headlines, gives us a frightening insight into the new skyscrapers that march across the urban and suburban skyline—the towering apartment houses and business complexes that experts have dubbed “fire traps in the sky.”

Lacking the more overt symbolism of The Tower, the Glass House is described in the first chapter as a “tower etched against the dark clouds”:

Sixty-six stories of gold-tinted glass panels and gold-anodized aluminum. The location on the north side of the financial district had been selected so there would be no buildings for several blocks around that could challenge it. There had been no compromise on the size of the site itself—the plazas on each side of the building were spacious and inviting, you didn’t feel crowded as you strolled across them to the building’s entrance. Sixty-six stories—thirty commercial and office floors and thirty-six of apartment floors—straight up with no setbacks. On the southern exposure, a sheer wall marked the utility core and served as a golden backdrop for the scenic elevator to the Promenade Room at the top. […] the most popular postcards in the local drugstores were those of the Glass House at night. It had become a symbol of the city.

The Glass House is a less audacious structure, described in chapter 31 as just “one of the tallest” high rises in the city, with similar construction problems as possible dangers, such as the “chimney effect” that would exacerbate a mid-building raging fire.

Building the Glass Tower

The Towering Inferno, along with its Allen-produced precursor The Poseidon Adventure (dir. Ronald Neame, 1972) and later films like Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (dir. George Lucas, 1977) helped establish the modern conception of the blockbuster film, specifically in their publicity, merchandising, and the narrative of production used to pitch the films themselves. So, The Towering Inferno was not only the top-grossing film of 1974 (and was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar), but was also promoted by highlighting the story of its production, specifically how its special effects were achieved, including extensive documentation of the model-making for the film’s two main towers.

Below are some of the variety of production materials that came out in relation to the film, sourced from a variety of fan sites, including The Towering Inferno Archive and The Towering Inferno Memorabilia Archive.

Parodies

And, as with other major blockbusters, The Towering Inferno received some light ribbing from parody magazines. Prominent among these was the six-page “The Towering Infernal,” in Cracked #126 (August 1975), with original art by John Severin:

And the eight-page “The Towering Sterno” in Mad #177 (September 1975), written by Dick De Bartolo, with art by Mort Drucker:

#The Towering Inferno (1974)#film#tower#Tower-ing Fiction#Shawn Gilmore#Die Hard (1988)#The Tower (1973)#Glass Inferno (1974)#prose

0 notes

Text

Discover Comfort and Convenience: Ajo Hotel Near IGA Store and Marine Motel

If you're planning a trip to Ajo, Arizona, and looking for a place that offers both comfort and convenience, finding an Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel is a smart choice. This quiet desert town offers visitors a unique mix of history, outdoor adventures, and modern amenities, and staying in the right location can enhance your experience.

Why Stay Near the IGA Store and Marine Motel in Ajo?

The area around the IGA store and Marine Motel in Ajo is known for its accessibility to local shops, eateries, and essential services. Choosing an Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel means you’re just a short walk or drive from groceries, fuel stations, local cafes, and the heart of the town’s activities. Whether you're a tourist exploring the nearby Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument or a road-tripper passing through, this area is perfect for easy access and hassle-free travel.

Comfortable Stays at the Ajo Marine Motel with RV Parking

One of the top options for travelers in the area is the Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking. Known for its friendly service and clean rooms, this motel offers a budget-friendly and comfortable lodging experience. What makes it even more attractive is the addition of RV parking, ideal for travelers touring in motorhomes or camper vans. The RV spaces are well-maintained and provide essential hookups, making it a preferred stop for RV adventurers.

Travelers appreciate the motel’s peaceful atmosphere and the convenience of having both motel rooms and RV spots in one location. Plus, its proximity to the IGA store means you can easily stock up on essentials or grab a quick snack without having to drive across town.

Attractions and Activities Near Ajo Hotels

When you stay in an Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel, you’re also close to some of Ajo’s top attractions. The Ajo Plaza is a charming area filled with Spanish Colonial Revival architecture, local art galleries, and occasional farmers' markets. Nature lovers will enjoy the short drive to Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge or Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, offering hiking, birdwatching, and scenic desert views.

For those staying at the Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking, you’ll find it's also a great base for exploring southern Arizona's rich mining history and desert landscapes.

Book Early for the Best Availability

Due to its desirable location, lodging near the IGA store and Marine Motel can fill up quickly, especially during peak travel seasons. Booking your room or RV spot in advance at the Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking or nearby hotels is recommended to ensure you get the best rates and availability.

Final Thoughts

Finding an Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel gives travelers the best of both worlds: a peaceful place to stay and proximity to essential services and attractions. Whether you're in a cozy motel room or parked in your RV, this convenient location in Ajo, Arizona, offers a restful and enjoyable experience for all types of travelers.

#Motel near Organ Pipe and Hwy 85#Ajo Motel near Organ Pipe#Marine Motel Ajo Arizona#Hotel near Organ Pipe National Monument

0 notes

Text

Places to stay in Ajo near Mexico border

Explore places to stay in Ajo near the Mexico border, a charming desert town offering unique accommodations just minutes from the U.S.-Mexico line. Choose from cozy inns, budget-friendly motels, or scenic vacation rentals surrounded by Arizona's rugged beauty. Perfect for travelers heading south or exploring nearby national parks, Ajo’s accommodations offer comfort and convenience for every adventure.

0 notes

Text

Cheap motels in Ajo AZ near IGA store

Stay at cheap motels in Ajo, AZ near the IGA store for a budget-friendly and convenient option close to shopping and dining. These motels offer essential amenities and comfortable rooms, perfect for travelers looking to explore Ajo’s attractions or head to the Mexico border. Enjoy a cozy stay with easy access to local stores and nearby Highway 85.

0 notes

Text

Hotels near Organ Pipe and Mexico border

Stay at hotels near Organ Pipe and the Mexico border for a perfect blend of comfort and adventure. Located close to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, these accommodations provide easy access to breathtaking desert landscapes and the nearby Mexico border. Enjoy cozy rooms, modern amenities, and ideal proximity to outdoor activities, making your southwestern journey both relaxing and memorable.

0 notes

Text

Hotels in Ajo near Hwy 85 to Mexico

Choose from top hotels in Ajo near Hwy 85 to Mexico for a convenient and comfortable stay close to the border. Perfect for travelers heading south, these hotels offer easy access to local attractions, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, and scenic desert landscapes. Enjoy affordable rates, cozy rooms, and essential amenities for a stress-free travel experience on Highway 85.

0 notes

Text

Cheap motels in Ajo AZ near IGA store

Stay at cheap motels in Ajo, AZ near the IGA store for a budget-friendly and convenient option close to shopping and dining. These motels offer essential amenities and comfortable rooms, perfect for travelers looking to explore Ajo’s attractions or head to the Mexico border. Enjoy a cozy stay with easy access to local stores and nearby Highway 85.

0 notes

Text

Discover the Best Hotels in Ajo Near Hwy 85 to Mexico

Located on the scenic route to Mexico, Ajo, Arizona, is a charming desert town known for its rich history and natural beauty. Whether you're passing through or planning a longer stay, finding the right hotels in Ajo near Hwy 85 to Mexico is key to a comfortable and enjoyable experience. One standout option in the area is the Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking, offering convenience and amenities for travelers of all kinds.

Why Stay in Ajo Near Hwy 85?

Hwy 85 is the primary route connecting Arizona to Mexico, making Ajo a popular stop for road trippers, adventurers, and seasonal travelers. Staying in a hotel near Hwy 85 provides easy access to the highway while allowing you to enjoy Ajo’s warm hospitality and stunning desert landscapes.

Benefits of Staying Near Hwy 85

Convenience for Travelers Located just minutes from the highway, hotels in Ajo offer quick access to dining, fuel, and local attractions, ensuring a seamless journey.

Proximity to Mexico For those heading south, staying near Hwy 85 positions you closer to the Mexican border, allowing you to rest before continuing your trip.

Explore Local Attractions Ajo is home to must-see destinations like the Sonoran Desert National Monument and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, perfect for nature enthusiasts.

Ajo Marine Motel with RV Parking: A Top Choice

For travelers seeking comfort and versatility, the Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking stands out as an excellent choice. Here’s what makes it a favorite among visitors:

1. Convenient Location

Situated near Hwy 85, the Ajo Marine Motel provides a perfect base for travelers heading to Mexico or exploring the local area. Its prime location ensures easy access to nearby attractions and amenities.

2. Comfortable Accommodations

The motel offers clean, cozy rooms equipped with essential amenities, ensuring a restful stay. Whether you're traveling solo, as a couple, or with family, the accommodations cater to a variety of needs.

3. RV Parking Facilities

One of the highlights of the Ajo Marine Motel is its RV parking. This is ideal for road trippers who prefer the convenience of staying in their RVs while enjoying access to motel amenities like showers and laundry services.

4. Friendly Service

Guests frequently praise the warm and welcoming staff at the Ajo Marine Motel. Their local knowledge and dedication to customer satisfaction make your stay even more enjoyable.

Tips for Choosing Hotels in Ajo Near Hwy 85

When searching for the best hotels in Ajo near Hwy 85 to Mexico, consider the following factors:

Proximity to Attractions: Choose accommodations that provide easy access to key landmarks like the Ajo Plaza and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge.

Amenities Offered: Look for hotels or motels with facilities like free Wi-Fi, parking, and pet-friendly options if needed.

Traveler Reviews: Check online reviews to ensure the property meets your expectations in cleanliness, comfort, and service.

Plan Your Stay in Ajo Today

Whether you're heading to Mexico or exploring Ajo's unique charm, staying at the right hotel can make your trip unforgettable. The Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking offers a blend of convenience, comfort, and affordability, making it a top choice for travelers near Hwy 85.

Book your stay today and experience the perfect mix of relaxation and adventure in the heart of the Sonoran Desert!

#Affordable hotels in Ajo Arizona#Cheap motels in Ajo AZ near IGA store#Hotel near Organ Pipe National Monument#Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel#Marine Motel Ajo Arizona#Ajo Motel near Organ Pipe

0 notes

Text

Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel

Stay at an Ajo hotel near the IGA store and Marine Motel for convenience and easy access to local amenities. Perfect for travelers, this location offers cozy rooms and essential services, just steps from shopping and dining options. Enjoy a relaxing stay in the heart of Ajo, with quick access to Highway 85 and nearby attractions like Organ Pipe National Monument.

0 notes

Text

Ajo hotel near IGA store and Marine Motel

Stay at an Ajo hotel near the IGA store and Marine Motel for convenience and easy access to local amenities. Perfect for travelers, this location offers cozy rooms and essential services, just steps from shopping and dining options. Enjoy a relaxing stay in the heart of Ajo, with quick access to Highway 85 and nearby attractions like Organ Pipe National Monument.

0 notes

Text

Ajo Hotel with Pool Near Organ Pipe: Your Ultimate Desert Getaway

Discover Comfort and Relaxation Near Organ Pipe National Monument

Looking for an Ajo hotel with pool near Organ Pipe? You’re in the right place. Ajo, Arizona, a hidden gem in the Sonoran Desert, is the perfect base for exploring the awe-inspiring Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Whether you're an adventurer, photographer, or nature lover, finding a hotel that combines comfort, convenience, and refreshing amenities like a pool is essential. Let’s dive into why choosing a hotel with a pool in Ajo can enhance your desert travel experience.

Why Stay in Ajo?

Ajo is the nearest town to the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a UNESCO biosphere reserve that showcases the beauty of the Sonoran Desert’s unique plant and animal life. Staying in Ajo gives you the advantage of being just a short drive from the park entrance, making early morning hikes or sunset photography sessions easy to access.

Unlike the more commercialized tourist areas, Ajo offers a quieter, more authentic Arizona experience. With charming architecture, local eateries, and art galleries, it’s a peaceful place to relax after a day of desert exploration.

Benefits of Choosing an Ajo Hotel with Pool

The desert sun can be intense, especially in spring and summer. Having access to a hotel with a pool provides the perfect way to cool off and unwind. After a long hike or scenic drive through the national monument, a swim can soothe tired muscles and help you rejuvenate for your next adventure.

A hotel near Organ Pipe National Monument that offers a pool is also ideal for families. Kids can enjoy their time splashing around while parents relax poolside with a cool drink. It’s a win-win that elevates your stay from basic to blissful.

Top Features to Look for in Ajo Hotels

When booking your Ajo hotel with pool near Organ Pipe, consider the following:

Proximity to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (within 30 minutes drive)

Clean and spacious rooms

Pool access year-round

Pet-friendly options

Complimentary breakfast or local dining recommendations

Wi-Fi and other modern amenities

These features ensure a comfortable and convenient stay while you explore the surrounding desert landscape.

Explore Organ Pipe National Monument with Ease

Staying close to the park allows you to make the most of your visit. From scenic drives like the Ajo Mountain Drive to hiking trails such as the Desert View Trail, there’s something for everyone. Wildlife sightings, stargazing, and guided ranger tours add even more value to your trip.

By choosing a hotel near Organ Pipe National Monument that offers a pool, you're not only getting comfort—you’re investing in the quality of your entire travel experience.

Final Thoughts

Don’t let the desert heat stop you from enjoying one of Arizona’s most stunning destinations. Book an Ajo hotel with pool near Organ Pipe and enjoy the best of both worlds: natural beauty and cool comfort. Whether it’s a weekend getaway or part of a longer southwest road trip, Ajo is your gateway to desert adventure and relaxation.

#Motel on Hwy 85 near Rocky Point#Motel near Organ Pipe and Hwy 85#RV-friendly motel in Ajo#Ajo Marine Motel with RV parking

0 notes