#Horror film history and yet it isn't a horror film at all. It's a tragedy. That isn't to say it isn't scary or at least unsettling

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

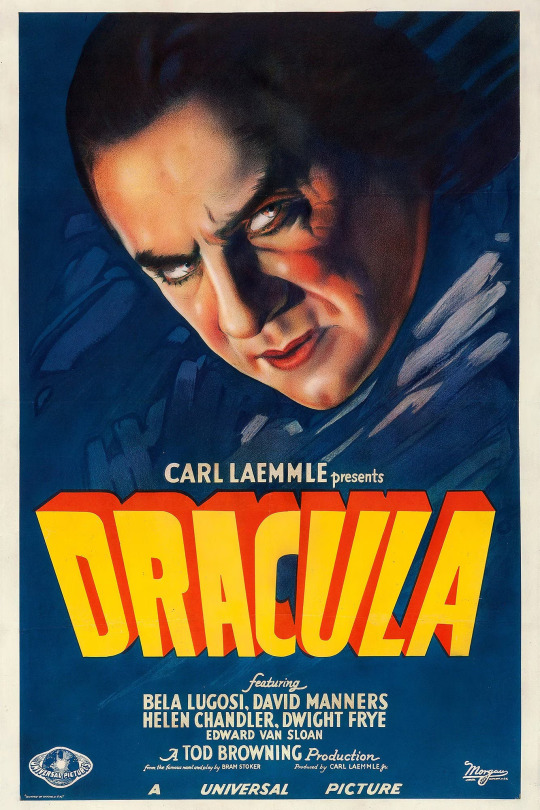

Horror Movie of the day: Dracula (1931)

The 1897 Bram Stoker's novel, a well known literary classic: the nefarious vampire who comes from beyond the Carpathians to take over England by settling in Cairfax Abbey, London. A blood eating fiend who is drawn in by the virginal Mina Murray, to then be confronted by her fiancé Jonthan Harker and Dr. Abraham Van Helsing. So when Tod Browning was hired to adapt it to the silver screen, from its theatre adaptation nonetheless, the end result became transformative in the world of cinema… forever.

Now, it's easy for modern audiences to be desensitized to its lack of violence and campy theatrics, with a performance from Bela Lugosi as the count that has been parodied to death and then some. And yet, over 90 years after it was seen for the first time it's still considered as THE iconic interpretation of the vampire upon which Halloween costumes are based on and from which many lines not found in the novel are imitated. Why is that? The key word is charisma.

Behind the obvious camp, there's something performative if not outright uncanny about the count. Yes, a 6 feet tall vampire who is always staring and cups the sky in his hand like a poorly directed Shakespeare villain can come across as a tad goofy, but he thoroughly sticks out and it's hard to look everywhere else when someone acts so strangely and somehow makes everyone start following his pace, simultaneously a relic of the time yet still captivating, magnetic even.

A pragmatic adaptation that simplifies the story (cutting out Lucy Westenra's suitors entirely, cutting Jonathan's trip Trannsylvania out) this film keeps most of the essentials about the book while optimizing the screen time, while changing the angle to emphasize the rivalry between Dracula and Van Helsing. The end result is moody and atmospheric, with some admittedly hooky effects but hitting just right at many moments.

It's only natural for a movie still worth watching.

Yes, I emphasized Lugosi's performance during the main body of review, but that was honestly warranted: a movie named after its antagonist lives or dies by that performance specifically, and the classically trained Hungarian honestly knocked it out of the park to the point he codified what vampires look like for decades, only horror film legend Cristopher Lee ever coming remotely close to the same leve of iconicity. But reducing the movie's success to JUST Legosi's performance is undermining the effort of the rest of the cast, with Edward Van Sloan's performance as Abraham van Helsing playing a great foil to the count, or Dwight Frye's compelling range as Renfield really selling the madness and tragedy of his character.

But above all, Tod Browning's directorial achievements in what was effectively a new field.

Sure, horror films existed before this one, so did Dracula adaptations even. But this movie had a challenge past ones didn't have to deal with: making horror work with sound. An herculean task he understood better than some people might give him credit for; while archaic to modern eyes with it's nigh total absence of music (including the now awkward use of Tchaikovsky's Swan's Lake as the opening credits theme), finding things like the sound creaking doors used to build tension THIS early in cinema history isn't as self explanatory as it might seem. It required an intuition as to how the soundscape of a situation instinctively affects the emotional state of the viewer.

That isn't to mention that for how shoddy those bats on strings look, the atmosphere of the film still manages to hit the mark. Even fairly goofy facial expressions can be rendered creepy under the right lighting conditions.

But then, there's some other matters about this film, like how the changes to the book have affected the perception of many characters (hitting Mina the hardest by making her JUST the damsel in distress), the fact Lugosi was not the first choice for Dracula and had to fight for it(showing that even back then you had an internal politics conflict in Hollywood), or the existence of a score which was added in later releases and adds to the film's atmosphere.

...or the fact it's actually TWO separate films from from the same script.

As dubbing and putting subtitles to films wasn't a common practice during the 30's, to export this movie to other markets a completely separate version in a different language would have to be made for each. And since Mexico is the immediate neighboring country, a Spanish version was shot at nights on the same sets as the English one, helmed by George Melford.

The end result is a very similar yet also decidedly different movie, lasting over half an hour more, addressing plot points that are either glossed over or shortly talked about, and having more ambitious cinematography, but with acting that doesn't quite match the overall level seen in Brown's effort. Specially poor Carlos Villarias, who was mandated to imitate Lugosi as close as possible and wasn't allowed to make the character his own, remembered only as a pale imitation of the so called original.

Still, a window into two different takes from the same script is a rarity in the world of cinema and well worth looking into.

#horror movies#horror films#classic film#universal monsters#tod browning#bela lugosi#david manners#helen chandler#dwight frye#edward van sloan#dracula#dracula 1931#roskirambles#carlos villarias#george melford

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Welcome to being a movie fan in the 21st Century, folks. It's not a new phenomenon for the weeks and months leading up to a major blockbuster to be filled with all sorts of hot takes and rampant speculation, but never have we been subjected to that through constant, unfiltered social media reactions. Sometimes, it takes the form of really fun and organic viral sensations (happy #Barbenheimer, one and all!) but, other times, you find yourself staring at a series of ill-informed and wildly off-base tweets making up the wildest claims about a movie — a movie which many of those opinionated individuals haven't even seen yet. "Oppenheimer," for better and worse, has been subject to both extreme ends of the spectrum.

That's not exactly a new development for Christopher Nolan, a director who has inadvertently attracted the most vocal movie fans out there. You'd be hard-pressed to find anyone without strong opinions on his "The Dark Knight" trilogy, but even his various original and non-IP films have given audiences a roadmap to tap into his biggest interests, fears, and fixations. That means the inevitable passage of time, recurring portrayals of dead wives/girlfriends, and the fact that the vast majority of his movies embody a very white perspective and worldview.

This is all present and accounted for in "Oppenheimer," admittedly, but a new wrinkle has been added to the mix. Ahead of Nolan's most overtly political film yet, certain segments of moviegoers have sounded the alarm bells and embraced a narrative that his interpretation of the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, "Father of the Atomic Bomb," might somehow justify the horrific killings of hundreds of thousands of innocents. Thankfully, those unfounded fears were never even a remote possibility in the first place.

'The power to destroy ourselves'

Somebody once wrote a line of dialogue about how "You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain," put it in their breakout superhero movie, and all but predicted how bad-faith detractors would attempt to take him down a peg for years to come. Was Chris Nolan a self-fulfilling prophet? A student of history? Or was he just someone with the common sense to look around him and recognize what was what?

If the past really is our best signifier of the future, then it feels truly misguided to look at the filmmaker's past body of work and jump to conclusions that "Oppenheimer" would take the most didactic approach of them all. Not that anyone as privileged as Nolan needs us to circle the wagons on his behalf, but he's clearly made a career out of taking the moral quandaries inherent within complex, oftentimes contradictory characters and testing these to their breaking point in the most extreme of circumstances. After all, that's how we end up with movies about Bruce Wayne becoming an outlaw to save Gotham City, a pair of dueling magicians losing themselves in their obsessions, and a profoundly broken, guilt-ridden man committing an illegal mind heist to be reunited with his kids. Even "Dunkirk," arguably the most straightforward tale of heroism in Nolan's filmography, ends not on the stirring image of a captured British warplane essentially burning in effigy, but a disconcerting close-up on the soldier who only just barely survived this ordeal realizing he'll soon be shipped out to face even greater dangers to come.

Does any of this suggest a storyteller who'd strip the horror out of the most horrific act in human warfare ... or, instead, interpret it as yet another cautionary tale?

'American Prometheus'

For the moment, forget the fact that "American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer," the imposing biography written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin that "Oppenheimer" is based on, refuses to pull any punches about the complicated legacy of its subject matter. Set aside the reams of documented, historical evidence that the United States' pretext for dropping the bombs on Japan was considered flimsy, even at the time. No, there's an even simpler explanation as to why "Oppenheimer" never even entertained the notion of being a "pro-nuclear bomb" movie: Where would any of the conflict or drama be in that?

There's a reason why the film begins with the haunting quote about the Greek god Prometheus stealing the fire of the gods and gifting it to us mere mortals ... only to be subsequently punished for eternity. Naturally, we then open on a young Oppenheimer already feeling tortured by visions of the quantum universe that only he can see — visions that, disturbingly, resemble violent nuclear explosions. Human nature, the film is practically screaming at its audience right from its earliest moments, will always trend towards self-destruction. Not only is this the quintessential archetype of a Nolan protagonist, but it's also the only dramatic interpretation of Oppenheimer's life that would merit devoting three whole hours to diving into his psychology.

There's a hypothetical, made-up version of "Oppenheimer" that would've actually lined up with the one concocted in the minds of the skeptics — one that's nothing but flag-waving jingoism (probably made by the same folks behind "Sound of Freedom") about how great America is at winning wars and proving doubters wrong. But the much richer text we received instead dares to confront horrible truths about our worst instincts. Because why else make this movie?

'Theory will take you only so far'

A little more than halfway through "Oppenheimer," after reports of Hitler's self-inflicted death and the fall of Nazi Germany come trickling in, the script goes out of its way to literalize the main conceit of the film. After Oppenheimer crashes a meeting of colleagues to discuss the effects of their "gadget" on the wider world, Nolan stages an actual debate about the ethics of dropping the atomic bombs on Japan. Informed that Japan's defeat seems "imminent" and that using their invention would inflict untold harm upon the world, Oppenheimer counters that world leaders can only "fear" and "understand" the weapon if they use it. When he offers up his pie-in-the-sky belief that all war will be unthinkable in a post-nuclear bomb world, the tepid applause his speech inspires only underlines his naïveté and denial.

Ever wonder how "Oppy" could convince himself to continue his work while compartmentalizing the devastating effects it would inevitably have on innocents caught in the blast? So does physicist Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), who bestows the "American Prometheus" title on Oppenheimer and calls for international nuclear disarmament. So does the security council, when Roger Robb (Jason Clarke) calls out Oppenheimer's hypocrisy over when exactly he first began to develop "moral qualms" about his work.

There are approximately dozens of examples like this throughout the mammoth runtime, where "Oppenheimer" doesn't really tip its hand so much as it slaps us in the face with the cold reality of the entire Manhattan Project. Theory will only take you so far, Oppenheimer's friend Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett) puts it early on. If only those who assumed this adaptation would be "pro-nuke" followed that advice, set their prejudgment aside, and just ... watched the movie.'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#The Dark Knight Trilogy#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Ernest Lawrence#Josh Hartnett#Roger Robb#Jason Clarke#Niels Bohr#Kenneth Branagh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I rather enjoyed Oppenheimer yesterday evening. Some random thoughts about it:

I was expecting it to be more introspective, focused mainly on the existential horror of, you know, a brilliant scientist, despite best intentions becoming the "destroyer of worlds". And that was certainly part of what the it was, and Cillian Murphy gives a brilliant performance, but for me at least, the film was much more about this inevitable march of the world towards tragedy. The film literally begins and ends with discussions of chain reactions, and the film itself portrays the biggest chain reaction of them all.

Part of it is that the storytelling felt ... "rushed" is the wrong word, it takes its time with long, indulgent shots, well written converations, and so on. And it's a three hour movie after all. But still, there is just so much ground to cover, so much relevant history and so many personalities (the namedropping gets a bit hilarious at time), that even extremely important events often really only get one mention, and then it's off to the next. This is a common problem in book adaptations, but in this case I didn't mind, because it contributed to this sense of rapidfire historical developments, you start to feel impressed the characters have time to breathe with all that is happening around them.

For most of the film, it all leads up to the Trinity test, and my goodness, I was surprised I felt such an intense mix of giddy anticipation and enormous dread. I mean, it's a historical event, we all know what happened, but still it felt like I was not prepared to actually see it. And it all unloads in this drawn-out explosion that is as awe-inspiring and despair-inducing as anything could ever be. It really felt like this was the moment a world ended and a new, worse one began: the one we are still living in. Again: The seeds for this were planted long before, and it was almost inevitable, but this really is the point of no return. The characters themselves react triumphantly, but this same mix of feelings I was talking about sort of gets subsequently delivered in the reactions to the Hiroshima bombing. I actually approve of the decision to not show this bombings of Japan at all, keeping it distant and intellectual. You have to put in effort to see it as real, yet at the same time there is zero doubt about it, you see the effects everywhere.

I was happily surprised by the very open discussions of politics. You are not forced into an opinion, but there certainly isn't a shortage of opinions to choose from. Oppenheimer usually gets the last word in discussions, but then again, by his own assessment, his principles led him astray, into designing the first nuclear bomb.

The long hearing about revoking Oppenheimer's security clearance for communist sympathies after the war works pretty well as a framing device. The framing device of the framing device was rather weird, like, I really didn't care all that much what happened to Lewis Strauss, but RDJ annoyingly portrays him extremely well, so at least it wasn't boring. And it did allow some remarks and details about Oppenheimer which would have been awkward to fit into the story otherwise.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jonathan Glazer rocks Cannes with a chilling Holocaust drama from a different perspective

CANNES, France

Jonathan Glazer's “The Zone of Interest,” a chilling Auschwitz-set drama shot through “a 21st century lens,” has delivered the Cannes Film Festival's first critical sensation by approaching the Holocaust from an unlikely perspective.

“The Zone of Interest,” which premiered to rave reviews Friday night, dramatizes the life of a fictional German family whose handsome home and tasteful gardens abut the outer wall of Auschwitz. There, they live a mostly peaceful, mundane life, while incinerators rumble in the background, smoke rises from the gas chambers, and muffled screams can be heard.

The father is Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), a Nazi commandant who designed Auschwitz, who lives with his wife, Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) and children. “The Zone of Interest,” loosely based on a Martin Amis novel, rigorously follows the family's daily lives while atrocity thrums next door.

“What it’s trying to do is talk to the capacity within each of us for violence, wherever you’re from, and to try to show these people as people and not as monsters was a very important thing to do,” Glazer told reporters Tuesday. “The great crime and tragedy is that human beings did this to other human beings.”

“It’s very convenient to distance ourselves from them as much as we can because we think we don’t behave that way," added Glazer. "But we should be less certain than that.”

Following its premiere, “The Zone of Interest" quickly rose to the top of forecasts for the Palme d'Or, the festival's top prize to be handed out May 27. Critics lauded the film's formal rigor in capturing the capacity of people to compartmentalize horror.

“The Zone of Interest,” Glazer's first film since 2013's grimly elegant science fiction “Under the Skin," proceeds largely without story in almost documentary fashion. It's set almost entirely in the orderly hallways and flower beds of the Höss home. Glazer said he and his filmmaking team, using up to 10 cameras at once, tried “to make ourselves as absent as possible, almost as authorless as possible.”

"It had so little to do with acting what we were doing," said Hüller. The process, she said, was more about being present.

Glazer sought to avoid movie tropes to bring viewers into a life they might recognize as their own, composed mostly of chores, work and child-rearing. For Glazer, it was about creating something “in present tense, not as a museum piece or something in aspic.”

“It needed to be presented with a degree of urgency and alarm,” said the 58-year-old British filmmaker.

Höss is based on Karl Bischoff, the concentration camp’s builder. A trip to Auschwitz, in which Glazer visited Bischoff's home, inspired him to make “The Zone of Interest,” which A24 will release in theaters at a not-yet-announced date. He returned to shoot it at the camp in Poland.

“It was never an option for it to be shot anywhere else," he said. "We tried to look for a place to shoot in other parts of Poland, but I kept gravitating back to Auschwitz.”

As in “Under the Skin,” Glazer uses a wide spectrum of techniques to create a densely layered visual and auditory experience. The score is by Mica Levi. Key in the process, Glazer said, was to avoid all the usual trapping of period films. Props were authentic but new. Glazer wanted a “present day” precision to make “The Zone of Interest” cut through history to reach today.

Glazer isn't the only British filmmaker in Cannes with a formally daring film that seeks to bridge Holocaust past with the present. Steve McQueen debuted his lengthy documentary “Occupied City,” which combines narrated accounts of Nazi atrocities in Amsterdam with present-day footage from those locations.

To Glazer, finding new ways to make the Holocaust real and immediate drove him to make “The Zone of Interest.”

“It's important to try to find a new paradigm for it so that a new generation can understand it," Glazer said.

0 notes