#Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I have been obsessed with Fort Meigs recently and the Ohio campaigns of the War of 1812, so this news article hit differently. The Ohio History Connection (the same organisation behind the Fort Meigs historic site) is trying to preserve a historic and culturally significant Indigenous earthworks from the golf course that has used it since 1910. The fact that this callous use of an ancient astronomy and ritual calendar site has been allowed to go on also reflects the violent removal of the Shawnee people who by all rights should have been there protecting and using the site. Imagine if they made Stonehenge a golf course!

This is all related to the War of 1812 and campaigns against the Shawnee, Potawatomi and Miami Nations. I have been thinking a lot about this since Indigenous Peoples' Day is Monday, and I have been thinking of writing up something with a predictable War of 1812 focus (there is a lot of material). It just goes to show how much the issues of the War of 1812 continue to affect the present day.

#war of 1812#indigenous#shawnee#ohio#us history#hopewell ceremonial earthworks#world heritage site#settler colonialism

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Y’all I am So Excited about this. The Serpent Mound and the other Hopewell mounds are one of the few genuinely cool things about Ohio

Excerpts:

"In the past we might sometimes say 'Hopewell culture' or 'Hopewell people,' but what we really understand 'Hopewell' to be now is not a new peoples," explains Bill Kennedy, site manager and site archeologist at Fort Ancient Earthworks and Nature Preserve. "It's a new religious movement of people. It's happening all throughout eastern North America. It reaches a fluorescence, though, in southern Ohio that it doesn't reach anywhere else."

…Chief Ben Barnes of the Shawnee Tribe, who was involved in the earthworks nomination, also sees its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a step toward combating racist and ignorant stereotypes about his people and his ancestors.

"They're great civil engineers. They're artists, they're astronomers, mathematicians, and for my people, that's not the way that Shawnee people, or any Indigenous peoples in this country, are typically portrayed in media," he says.

In addition, the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks address gaps in the World Heritage List identified by the World Heritage Committee. Specifically, a lack of sites representing pre-contact Indigenous American sacred architecture and sites that represent early understandings of science, culture and astronomy.

…Today no federally recognized tribes remain in Ohio. They were all forcibly removed in the 17 and 1800s. Yet it was their ancestors who created these massive feats of design and engineering.

Glenna Wallace is chief of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and has been active in the World Heritage process. She says inscription on the World Heritage List is part of her mission to teach people about the earthworks that her ancestors built.

She says their inclusion would not be an ending, but another beginning.

"Our people may have been forced away from that place, and they may have disappeared, but what they built, what they constructed, what their values were, that's still there and that should be protected," she states.

"That's the reason for World Heritage."

In becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site, Wallace says she hopes the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks will finally attain the reverence and respect they deserve.

See the linked article for more details!

#indigenous culture#native american art#Native American archaeology#Indian mounds#Native American mounds#hopewell#unesco#Shawnee

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

"UNESCO World Heritage Committee Names Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks to Prestigious List" (19 September 2023):

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee on Tuesday, September 19, 2023 named the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, a group of eight ancient earthwork sites in southern Ohio, to its World Heritage List. The decision by the World Heritage Committee was made by consensus at its 45th session in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The monumental earthworks were built 2,000 years ago by Native American communities. Five of the earthwork sites are managed by the National Park Service and three are managed by the Ohio History Connection.

The destination was applauded by U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), whose department oversees the National Park Service.

“Today’s designation by UNESCO is a tremendous opportunity and recognition of the contributions of America’s Indigenous Peoples,” Haaland said in a press release. “World Heritage designation is an opportunity for the United States to share the whole story of America and the remarkable diversity of our cultural heritage as well as the beauty of our land. The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks are unique creations of America’s indigenous people and a remarkable survival of our ancient history.”

The sites that comprise Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks were built between 1,500 and 2,200 years ago by people now referred to as the Hopewell Culture. The earthworks, built on an enormous scale and using a standard unit of measure, form precise squares, circles, and octagons as well as a hilltop sculpted to enclose a vast plaza. The geometric forms are consistently deployed across great distances and encode alignments with both the sun’s cycles and the far more complex patterns of the moon. Artifacts, which are among the most outstanding art objects produced in pre-Columbian North America, show that those who built the earthworks interacted with people as far away as the Yellowstone basin and Florida. These are among the largest earthworks in the world that are not fortifications or defensive structures.

The properties comprising the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks:

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park in Chillicothe, including the Mound City Group, Hopewell Mound Group, Seip Earthworks, High Bank Earthworks and Hopeton Earthworks

The Ohio History Connection’s Octagon Earthworks and Great Circle Earthworks in Newark and Fort Ancient Earthworks in Oregonia

During a recent vote, the World Heritage Committee members agreed that these earthworks deserve to be recognized alongside such places as Stonehenge in England and the Nazca Lines in Peru, as well as other iconic places in the United States, including Independence Hall and the Grand Canyon. The National Park Service manages all or part of 19 of the 25 World Heritage Sites in the United States. It is also the principal U.S. government agency responsible for implementing the World Heritage Convention in cooperation with the Department of State.

The inclusion of a site in the World Heritage List does not affect U.S. sovereignty or management of the sites, which remain subject only to U.S., state and local laws. Detailed information on the World Heritage Program and the process for the selection of U.S. sites can be found at the National Park Service’s website.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here in Ohio, we recently received a UNESCO World Heritage Site designation for the Hopewell Mounds Ceremonial Earthworks. They were made by what is now known as the Hopewell culture approximately from around 500-800 BCE. This complex covered 130 acres and include an earthwork that could have enclosed four Roman Colliseums; they are the largest geometrically shaped earthworks on the planet.

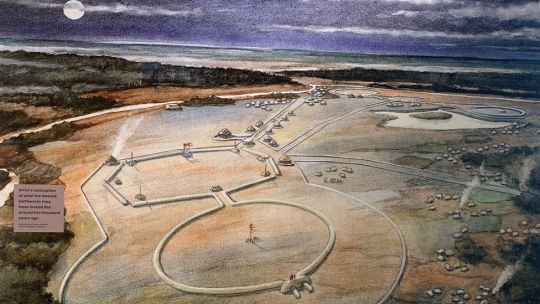

This is what it's believed they looked like:

Note the enclosure and consider how much work it must have been to put all of that earth there on southern Ohio's relatively flat fields. It was a grand undertaking that took decades, even centuries, of hard work. Rome wasn't built in a day, and the Hopewell Mounds weren't either.

Burials have been found in the mounds, as well as evidence of ceremonial gatherings that would have drawn people from all over the Eastern United States. BTW, the Hopewell Mounds are not just one single site; they are a vast network of separate earthworks all over the state that were connected by routes and were used in rotation.

Inside the mounds were found wonderful artworks from as far away as Yellowstone and the Gulf of Mexico, signifying long and complex trade networks:

What's most fascinating is that these giant complexes took generations to build ... and they are aligned to specific cosmic events. These enormous structures are essentially a depiction of the cosmos, including sun and moon cycles.

This map from the Newark Earthworks shows exactly how precise and beautiful the geometry of these mounds was:

So why have you, dear reader, never heard about them before now? Surely this incredibly ceremonial earthworks, vaster and more complex than Stonehedge, the largest mound structure in the world, an entire cosmological representation on earth, would be legendary.

Well, the reason you never hear about it is because the most intact and carefully-studied sites look like .... this now.

European colonizers FARMED OVER these beautiful ancient earthworks. They put a GOLF COURSE on top of gorgeous, culturally priceless artifacts of an advanced culture. (That golf course is still there, btw, and they're being quite stubborn about leaving despite the fact that this is now, you know, a World Heritgage Site.)

If you ever wonder why it seems like European has all the ancient historical places and no one else does, that's because they tore down, bombed, or built golf courses on top of everyone else's.

My favorite thing is that Europe is spooky because it’s old and America is spooky because it’s big

#just really fucking sick of the smug 'hahaha America doesn't have any old structures'#we did#you just DESTROYED ALL OF THEM#and before you go 'boohoo the Americans were the ones that built golf courses there'#Golf is from Scotland girl y'all brought it here

421K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hopewell Culture Ceremonial Earthworks

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

"They're great civil engineers. They're artists, they're astronomers, mathematicians, and for my people, that's not the way that Shawnee people, or any Indigenous peoples in this country, are typically portrayed in media." Chief Ben Barnes of the Shawnee Tribe

Tana Weingartner for NPR: "Ohio's Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks are about to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site"

"Of just over a thousand [Heritage] sites worldwide deemed of universal importance and value to humankind, there are only 24 in the United States that carry that distinction."

Outside the Great Circle at Newark (with visitor for scale, to the left in the distance). The Circle’s earthen berm stands anywhere from around 6 feet, to 14 feet high. Jake Wood

"Now, after more than a decade of work and planning, ancient earthworks in Ohio are poised to join them...

The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks encompass eight sites — a collection of historic earthen mounds built by Indigenous peoples:

Fort Ancient Earthworks and Nature Preserve

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (five geographically separate elements)

Mound City Group

Hopewell Mound Group

Seip Earthworks

High Bank Earthworks

Hopeton Earthworks

Newark Earthworks

All the sites were built 1,600 to 2,000 years ago by peoples formerly referred to as Hopewell...

It might be unusual to consider huge mounds of dirt as anything significant, however, UNESCO calls the earthworks a 'masterpiece of human creative genius.' That's one of the criteria for inclusion on the World Heritage List. Another calls for bearing "exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared."

The design and construction of the Earthworks show the people during this early era had a clear understanding of geometry, architecture, and solar and lunar alignments and multi-year cycles."

Full story with audio from Weekend Edition Saturday.

In my various travels, I've visited some of these; more information on some of those astronomical alignments is on available on Jake Rambles n'at, including diagrams on satellite views ('cause I do that):

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Ferris-Wright Park

4400 Emerald Pkwy.

Dublin, OH 43016

Located at the northeast corner of Emerald Parkway and Riverside Drive, Ferris-Wright Park (4400 Emerald Parkway) preserves and showcases the ancient earthworks, farmhouse and natural features of the space that are a significant part of Dublin’s history. The land surrounding the park has been home to many over the years, from indigenous peoples thousands of years ago to some of Dublin’s first settlers and 20th century residents. Ferris-Wright Park contains several earthworks—precise geometric shapes that hold meaning and purpose—constructed by the Hopewell People. An interpretive center located in the historic Ferris family farmhouse honors the past through interactive stations that tell the stories of inhabitants through the years.

The indigenous peoples of the Hopewell era represent tribes known for building earthworks – precise geometric shapes that hold meaning and purpose – in the Ohio Valley. “Hopewell” was the name of the family on whose land these earthworks were first noticed in Ross County, Ohio, in the 1800s. The Hopewell People lived, hunted, fished and farmed in what is now Ohio and other parts of eastern North America around 100 B.C. to A.D. 400. They were an advanced society with an extensive trade network that ran from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and out west to the Rocky Mountains. They had a sophisticated understanding of geometry and astronomy, and these principles were demonstrated in their ceremonial spaces known as earthworks, which provided places for gatherings of people, just as American Indian people continue to do today.

The earthworks were places for ceremony, for marriages, to honor relatives and neighbors who died, to make alliances, for celebration, feasting, and sacred games. Today, few of these ceremony spaces remain intact. Many have been damaged or cleared away for farming and development. The earthworks at Ferris-Wright Park are the northernmost earthworks in the Scioto valley. Many groups of tribes are represented at this site, with the oldest dating back to Clovis times, or about 12,000 years ago. The park contains three earthworks (two circles and a square) and five burial mounds. The tallest mound once stood five feet tall and the others were approximately three feet tall.

The earthworks were explored by local farmers and villagers for many years before being professionally excavated in 1890, 1922 and 1961. The artifacts retrieved during these digs helped archeologists better understand the people of the Hopewell culture. The Ohio State University Department of Anthropology led archeological digs at the site in 2013, 2014 and 2016, discovering fascinating artifacts such as prehistoric stone tools and debris from making such tools, as well as historic pottery. They also uncovered modern debris from a few years ago, to their oldest find, a Clovis point – a type of prehistoric tool made by native peoples of North America – dating to around 13,000 years ago. Ohio Valley Archaeology led geophysical surveys in and around the site, creating a clearer picture of the earthworks.

Early settlers explored the Ohio region in the 1800s, drawn by rich soil and abundance of natural resources, water and game. The first farmers in the Dublin area tilled and plowed the land by horse-drawn iron equipment. Wheat and hay and perhaps alfalfa were among the first crops to be planted, but corn, potatoes, beans and other vegetables provided annual sustenance for a farm family. Wright Run Creek, which runs through Ferris-Wright Park, irrigated early farms. Rivers, like the nearby Scioto River, were used for milling and other industries that brought prosperity to Dublin. Joseph Ferris came to Ohio in 1818, eight years after Dublin was platted as a village. Ferris cleared the land for farming and built his farmhouse in 1820. It is said that his house was the first frame house in the area. The others were all log houses or log cabins. The restored home still stands today and welcomed visitors to the park in the fall of 2018, 200 years after Ferris came to the area.

0 notes

Photo

The US' 2,000-year-old mystery mounds - BBC Travel

Constructed by a mysterious civilisation that left no written records, the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks are a testament to indigenous sophistication.

Autumn leaves crackled under our shoes as dozens of eager tourists and I followed a guide along a grassy mound. We stopped when we reached the opening of a turf-topped circle, which was formed by another wall of mounded earth. We were at The Octagon, part of the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, a large network of hand-constructed hills spread throughout central and southern Ohio that were built as many as 2,000 years ago. Indigenous people would come to The Octagon from hundreds of miles away, gathering regularly for shared rituals and worship.

"There was a sweat lodge or some kind of purification place there," said our guide Brad Lepper, the senior archaeologist for the Ohio History Connection's World Heritage Program (OHC), as he pointed to the circle. I looked inside to see a perfectly manicured lawn – a putting green. A tall flag marked a hole at its centre.

The Octagon is currently being used as a golf course. ...

... However, after the Hopewell Culture gradually began to disappear starting around 500 CE, other indigenous peoples stepped in to become caretakers of the land. One of those groups was the Shawnee Tribe, which called Ohio home before they were forcibly removed west of the Mississippi River in the 1830s.

"We may not have been responsible for building or creating them, but I know that my ancestors lived there, and that my ancestors protected them and respected them," said Chief Glenna Wallace of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, who believes that other tribes should have a role in the future of protecting the Hopewell Earthworks and communicating their cultural importance.

However, receiving Unesco status is a difficult, bureaucratic process. While sitting on land owned by the OHC, The Octagon is under the control of the Moundbuilders Country Club. The club negotiated an unprecedented lease that extends until 2078 and only allows visitors to walk the mounds four times a year. The rest of the time, visitors can access a platform in the car park to view a very small section of the property. OHC is currently suing to evict the country club (with compensation) through eminent domain. The lower courts ruled in favour of the historical society, but the Ohio Supreme Court is hearing an appeal. If OHC can't guarantee public access, this may affect Unesco's decision.

While a Unesco designation wouldn't entail the return of land or reparations, it does mean greater local representation and education about Ohio's Native American history. It also means more indigenous stakeholders, like the Shawnee, telling that story from an indigenous perspective for future generations.

"I just want people to know about it," said Chief Wallace, "I want people to be able to see it. I want people to be able to visit it and want people to realise that it is a cultural phenomenon. That it's priceless."

37 notes

·

View notes