#Hockney Homage

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

©2024 Garth Buckles

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

I see a lot of folks noting the things Ted Lasso has in common with Sleepless in Seattle after Ted said it's the superior Nora Ephron film.

And, yup, I did a rewatch of the film (it's one of my favorites) and took notes too just like a lot of you lol.

There are the obvious things of course. The whole soulmatey-destiny-cosmic-forces vibe, signs (that the heroine is a skeptic of), a focus on planes and boats, an Oklahoma reference, Dr. Fieldstone (who begs people to just talk to each other and admit their feelings). There are Wizard of Oz nods too: Somewhere Over the Rainbow plays after the first radio show, when Annie hears Sam for the first time, Annie and Walter's dinner at the Rainbow Room, Sam mentioning growing a new heart, the reference to a friend named Glenda.

But being the tedbecca clown and yoga enthusiast I am (*proudly adjusts clown wig before stretching*), here are a few other things I noticed:

When Victoria is traveling, she offers to bring Noah a snow globe from the place she's visiting.

The quote: "What we think of as fate is just two neuroses knowing that they are a perfect match." "Y'all's baggage just matches right up, don't it?"

When Annie stops at the diner, she orders tea.

Jonah's Seattle Mariners hat matches the believe colors, and (I know but I stretched before this reach) at the end of the movie, when Sam and Annie hold hands for the first time, he's wearing a yellow jacket and her coat is blue.

And, my favorite (I honestly gasped), the host who seats Sam and Victoria when they first meet for dinner is named...Derick.

Now for my Affair notes:

Sleepless in Seattle paid homage to An Affair to Remember, so let's think about that movie in relation to Ted Lasso, too.

(Before I really dig in, we all know from both movies about the Empire State Building and February 14, but do you remember the teaser trailer for this season was dropped on Valentines' Day?)

Now, in Nora Ephron's Sleepless, the movie and especially the ending of Affair was touted as the most romantic thing ever.

To summarize it: The heroine (Terry) and hero (Nickie) meet while they're involved with others and take a quick "friends to lovers" journey. They realize their feelings and vow to resolve the issues keeping them apart (relationships, careers), and then meet in six months at the top of the Empire State Building. When that day comes, Terry's hit by a cab while rushing to meet Nickie...and Nickie waits in vain in the rain and thunder and lightning until he gives up, thinking she doesn't love him. She won't tell him about the accident because it left her unable to walk. Nickie visits Terry in her apartment and is just about to leave forever when he sees one of his paintings (that his agent gave to a woman in a wheelchair) and realizes what happened. Love and happiness ensues.

So:

-Ted and Rebecca aren't involved with others when they meet, but they are very hung up on their exes, and they have to work through their issues before they're ready to be in a relationship with someone.

-There's been debate for a while in the general Ted Lasso fandom about the show foreshadowing a car accident. Ted even almost steps in front of a car a few times.

-Rebecca's "thunder and lighting" haven't happened yet.

-Ted's not a painter like Nickie, but the Hockney drawing that Rupert gave Rebecca is important to her journey. And this show likes parallels, so I've been thinking about how a drawing/painting/piece of artwork involving Ted might play a part in an eventual tedbecca. I've wondered if he might get her a copy of one of Hockney's lightning prints because he knows she likes the artist.

I don't know.

I'm not thinking Ted and Rebecca will vow to meet at the top of the Empire State Building or anything like that. But I have long thought any revelation of feelings between Ted and Rebecca would be in the very ending of the show, just like in Sleepless in Seattle.

(*puts on clown shoes*)

Now I'm fully into the idea that a car accident, thunder and lightning, and possibly a painting...all in homage to An Affair to Remember...will play a part in the realization of feelings and ensuing confession.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Copper Jug Fall…homage to Duchamp and Hockney. The latter used photo collage with his Nevada Desert work the best example. The former painted his lady walking down the stairs.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homage to gay male artists, from Michelangelo to Francis Bacon and David Hockney ♀️🏳️🌈

#women artists#women's art#lgbt art#pride month#gay pride#homage#gay male artists#michelangelo#francis bacon#david hockney

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

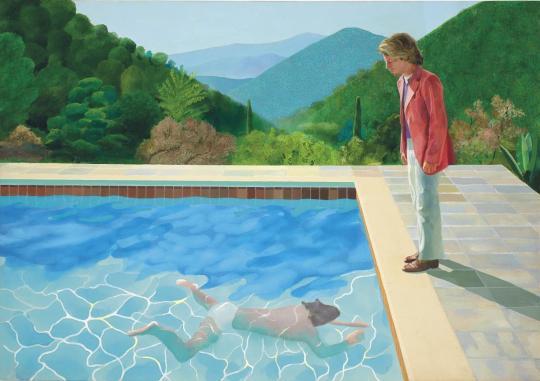

MWW Artwork of the Day (7/8/22) David Hockney (British, b. 1937) Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)(1972) Acrylic on canvas, 213.5 x 305 cm. Private Collection

Hockney came of age in Britain's Mod Sixties and his paintings often have the glitzy, hip look of that era. Born in Yorkshire and educated at some good public schools, he attended the Royal College of Art in the late 1950s, where he befriended the American expatriate artist R.B. Kitaj. Where Kitaj's paintings are intellectual and redolent with historical associations, Hockney's work is the epitome of British Pop, a sort of fusion of Andy Warhol and Edward Hopper, iconic images of the Affluent Society rendered with breath-taking precision in Technicolor and a super-realistic style. After a 1963 visit to New York to pay homage to Warhol, he made a pilgrimage to southern California (the "Mecca of the Modern"), which inspired him to do a series of pictures (in acrylic) featuring (what else?) swimming pools.

Hockney is one of the featured artists in this MWW gallery/album: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.571541662951207&type=3

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Student – Homage to Picasso, a work form The Hepworth Wakefield collection, pays homage to one of Hockney’s heroes, a young Pablo Picasso, in which the artist is literally put onto a pedestal.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

David Hockney - The Student from Homage to Picasso, 1973

Source: moma.org

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Horseman by Bendik Kaltenborn

date: unknown

Method: digital illustration

This piece looks to be inspired by the David Hockney piece called a bigger splash. The environment behind Bojack the character is replicated from the Hockney painting. The digital illustration uses vector images and shading to create the aesthetic of Hockney’s style infused with new technology and Kaltenborn’s own artistic preference. The piece is a homage and a wonderful one at that.

The context to why this piece is so important not only as a piece but with it’s references to Bojack the show as a fan is huge. In Bojack we see the famous Hockney painting ‘Two With Two Figures’ numerous times during the show in Bojack’s office. The painting is referenced in some nightmares of Bojack’s.

In the show the Hockney painting is modified with Bojack looking at Bojack instead of what the original has. But not only is the references to Hockney the best part of this illustration, but it is the subtle references to Bojack as a character.

Throughout the show and even in the opening of the show Bojack is seen falling off his balcony in the ‘Hollywoo’ hills into his pool. The imagery of bojack jumping into water and drowning in his pool are very strong throughout the show. His own idol secratierate who died by jumping off a bridge strengthens the deeper meaning of water that the show creates. This feeling of drowning in fame, sadness, regret and all of Bojack’s worst traits. Are all shown through this one image.

Bojack is holding an alcoholic beverage in his hand representing his alcohol addiction and he is also holding a cigarettes' showing his smoking problem too. The suit represents the intro, during the intro he is wearing a tux and drowns in his pool after falling. This photo makes references to that small detail too. The bottles on the roof and all over the house also hint to his drinking problems.

In the back of the image you can see silhouettes of princess Carolyn one of Bojack’s only friends and his agent. The shape of her silhouette shows her with her hands on her hips representing yet again Bojack has done something stupid.

The expressions on Bojack’s face perfectly represent the type of mental state Bojack has a character. He is nihilistic and doesn’t care about much, he clings to his pasts days as a sitcom actor in ‘Horsin around’ a show that is modeled after the Cosby’s. But it’s not just that the references stop their, like Hockney Bojack is in paradise and like some of the meanings in Hockney’s work he isn’t happy all though he has everything he could have asked for. Bojack just like in the show still deals with all of these issues while living paradise. He is as some would say suffering from success.

This all comes together to give what viewers understand as what Bojack is, a person with mental problems suffering in silence seeking attention for all the wrong reasons. Bojack is simply Bojack.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/08/bojack-horseman-bleakness-and-joy

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Girl reading, Silvina Resnik

These series of paintins, presented in my portfolio, are some kind of intimate portraits. The title of these series, “Between books, between dreams”, refers to the time between asleep between awake. That confused moment in which I don´t know what reality is. It is also about the changes produced in my mind when reading a new good book. I´m interested in reality, in the question of what reality is. These are portraits of teenagers in that moment of life when there are many doubts, in which it´s not known what to do and everything is uncertain, unclear. These paintings emerged, on one hand, because of my interest in painting some interior scenes with teenagers reading, resting or sleeping. On the other hand there is a relationship between these paintings, some drawings with the same title and others made some years ago with the same girls when they were children. I guess I am searching something in relation with time, movement, uncertainty and changes. In these works there is also a reference to the past, to my adolescence, when there were no digital books. These series of works are also a sort of homage to painters and writers (Henry James, Matisse, Hockney) who have influenced my work and changed my way of seeing the world. There is also my interest in portrait, more in a universal way than in an individual way. The starting point of these paintings was taking some pictures. First I made some photographs of some friends of my son lying in sofas in my living room, trying to recreate, like in a theater, the past time shared with my sisters. Time of reading, talking, staying together doing nothing. Then, from the photographs, like a reference, I made these paintings.This painting is made on acid free paper

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-Girl-reading/335840/3477259/view

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Corey Helford Gallery presents 'Machine Man Memories', a solo art show from Eric Joyner, showcasing 18 new oil paintings, promising to fulfill the viewer’s need for robots, donuts and yes, cats. Joyner has also created an homage to a living artist, David Hockney (British painter, stage designer, and photographer) as well as bringing to life some non-robotic figures such as Frosty the Snow Man, Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer, The Wizard of O’s, and a dragon to his surreal body of work.

The opening reception is on Saturday March 7 from 7pm-11pm PT at Corey Helford Gallery, 571 S Anderson Street (Enter on Willow Street), Los Angeles, CA 90033 in the Main Gallery, alongside a solo show from Adrian Cox, entitled 'Into the Spirit Garden', in Gallery 2, and a solo show from Kelsey Beckett, entitled 'The Amber Orchard', in Gallery 3.

The exhibition will be on view through April 11 2020.

#Art#Eric Joyner#Corey Helford Gallery#New Contemporary Art#Contemporary Art#Pop Surrealism#Surrealism#Robots#Donuts#Original Art

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shower room - Homage to David Hockney(2019)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

David Hockney

The Student from Homage to Picasso (Hommage à Picasso) 1973

Aquatint and etching

MoMA

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

JACQUEMUS SPRING MENSWEAR 2020

visible tan lines?!?!? I dig it

hat shaped like an avacado?! what’s not to love

A round of applause of monsieur Jacquemus, for he has done it again, on his 10th Anniversary he has successfully delivered beautiful clothes all while grabbing our hearts. It comes to no surprise that Simon Porte Jacquemus and his creative and talented mind created such detailed and dainty garments for this years spring/ summer menswear collection. There is one thing I have always respected monsieur Jacquemus for and that is how unapologetic he is with his creations. With every show and garment created it is almost like he’s creating paintings. A quotation from him in an interview with Vogue said “I wanted it to look like a David Hockney painting or a Christo installation through the fields,” he said. “With lots of prints. A painting within a painting, in a field. Provençal Pop!”, and I must say he has without a doubt outdone himself, with the perfect location, colors and silhouette, it is easy to say that “Le Coup De Soleil” is one of the most memorable shows for menswear 2020. Now let’s break down the show one by one, shall we.

As mentioned previously, Jacquemus was inspired by an art installation David Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Hampshire, 2011, as well as Christo and Jeanne-Claude which works were all about environmental art. With the two combined, Jacquemus created every fashion show fairytale of a 500-meter fuschia catwalk, sandwiched in the middle of a lavender field. Naming the show “Le Coup De Soleil” which when translated means “The Sunburn” was absolutely brilliant, Jacquemus paid homage to this by giving out baby bottles of SPF50 as invitations to the guests and by also creating detailed tan lines on the runway models, what did i say? Jacquemus serves us all the details and never leaves without doing so, and it blows. my. mind.

Right onto the most important part, the clothes!!!!, Jacquemus always does spring/ summer just right, hits all the right vacation feels. Soft tones of pastel, and lot and lots of flower prints, Jacquemus is really ending toxic masculinity isn’t he. Not to mention, the oversized shirts on female models, the bright prints and pinks on the males, it is almost like the show wanted to wash away all gender roles and allow clothes flow like clothes on the body, which I am sure we are all so grateful for. With each stride the models take, the more the clothes dazzled under the French sun, and that also must be credited to his collaboration with Swarovski by adding sparkles of over 385,000 crystals on both women and men garment’s, shoes and accessories. Jacquemus’s infamous artsy and dainty shoes made a debut as well as his odd proportioned bags (a little on the tiny side but definitely filled with love). We have also seen Jacquemus creating huge hats, normally in the khaki brown color, but now, it’s in pastels!. I mean come on, did you see the avocado hat? I am still not over it, and I don’t think I ever will be.

All in all, the show was spectacular, you can definitely see Jacquemus love and devotion into each collection he produces, and with that I must say he deserves every recognition he is receiving.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Interiors & Identity- Mary Finlayson

Navigating the themes of intimacy, memory, and self, Mary Finlayson’s gouache paintings reflect the vulnerable narratives unveiled through ownership of possessions. JoAnne Artman Gallery is proud to announce Finlayson’s addition to the gallery’s roster, with works currently at JoAnne Artman’s Laguna Beach location. Flattening the perspective of each scene, her still lifes provide a voyeuristic glimpse in to each curated space. While showcasing a bold color palette and emphasis on texture, Mary Finlayson’s interest in painting interior spaces portrays how environments reveal identity.

Interior II

, Gouache and Flashe on Canvas, 48” x 48”

Considering the personal attachments and importance of objects, Finlayson starts her process by flattening an interior modeled after a photograph or memory. She then skews the room’s objects and alters the colors with an unexpected, vivid palette. Paying homage to the iconic works of David Hockney, Henri Matisse, and Stuart Davis by borrowing similar bright color palettes, repetitive patterns and reduced, simplified forms, Finlayson creates complexly structured scenes in her own distinctive style.

Interior I,

Gouache and Flashe on Canvas, 48” x 48”

Creating environments that are partly real and partly imagined, Finlayson’s ability to craft a story by way of her art is enigmatic. Considering interiors as portraits that contain their own narratives, her compositions explore the stories that each space tells about the people who inhabit them. Capturing the intimacy of the interior, each of her creations, her energetic lines evoke movement that helps enliven the otherwise stagnant settings.

Blue Box with Spider Plant, Gouache and Flashe on Canvas, 36” x 30”

Finding balance between form, color, and a narrow depth of field, Finlayson’s work prioritizes the feeling of the space over accuracy in order to effectively communicate the underlying identity of each interior.

Yellow Chair

, Cotton Hand Dyed, Hand Woven Textile,

72” x 48”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decolonising the Curriculum

Art history lags behind other disciplines in incorporating art by black and ethnic minorities argues Richard Hylton

Source

Image: Frank Bowling, South America Squared, 1967

Frank Bowling’s forthcoming major retrospective at Tate Britain has been a long time coming. So long, in fact, that visitors to it will be able to ‘experience’ what Tate describes as ‘the entirety of Bowling’s 60-year career’. As ‘one of Britain’s most visionary painters’ who ‘went on to study at the Royal College of Art alongside David Hockney and RB Kitaj’, and who ‘became the first Black artist nominated as a Royal Academician’, Bowling has finally been recognised by the upper echelons of the UK art establishment. Like Rasheed Araeen’s retrospective in 2017-18, organised by the Van Abbemuseum in Eindoven before touring to the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead (as well as Geneva’s MAMCO and Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art) that charted Araeen’s 60-year career (Interview AM413), Bowling’s retrospective characterises recent institutional attempts at slowly inserting black artists into British art history. It is difficult to overstate the significance of these exhibitions. Both Bowling and Araeen are in their 80s. Furthermore, these shows mark a break from posthumous recognition bestowed on artists such as Ronald Moody, Aubrey Williams, Anwar Jalal Shemza and Donald Rodney.

Accompanying the display of substantial bodies of work spanning several decades are equally substantial monographs on Bowling and Araeen respectively, which include essays by a coterie of curators, critics and art historians. These exhibitions and monographs reflect the museum sector’s continuing attempts to diversify the canon. But is academia’s instrumental contribution to these exhibitions evidence of a move towards expansive and pluralised notions of art history? In any number of retrospective exhibitions staged in the UK over the past few years, including those on Hannah Höch, Eva Hesse, Thomas Ruff, Käthe Kollwitz and more recently Joan Jonas, Anni Albers and Franz West, academics often play key roles, be it as curators, writers or advisers. Often testament to their sustained and prolonged academic inquiry, it follows that these artists figure prominently in course offerings on modern and contemporary art. Given that postwar black artists have been largely excised from dominant art history narratives, is the academy suitably equipped to follow the museum sector in diversifying its curriculum or does its role in historical revisionism mask prevailing racial and cultural hierarchies within art history? This article considers the racial and cultural politics of academe in the UK today. It argues that while feminist-based theories, for example, have played an instrumental role in challenging notions of the canon, conversely post-colonial discourse in its many forms, though equally important, remains largely marginalised if non-existent across the course offerings of many art history departments in the UK. Concepts of difference and pluralism are presently more widely reflected in the UK, not least by universities eager to project themselves as tolerant and inclusive environments. However, from their curricula to employment practices, academe remains largely impervious and resistant to change. Is this a consequence of an unspoken white privilege which continues to pervade and dominate the field of art history?

In 2000, as part of a presentation for my MA in History of Art, I explored the politics of black artists in British art. Ruminating on why Bowling had been and continued to be frozen out of mainstream narratives of British art, I showed Who’s Afraid of Barney Newman, 1968, from Bowling’s now widely acclaimed map paintings series. The paintings represented an amalgamation of ideas pertaining to abstraction and representation, culture and identity, as well as being a witty homage to the revered US painter Barnett Newman. Comprising shimmering green and red sections, intersected by a luminous yellow crevice, reminiscent of Newman’s signature ‘zip’ motif, a faint but discernible white outline of the map of Guyana, Bowling’s country of birth, reinforced the interplay between representation and abstraction. This confluence of narratives and entry points to Bowling’s work were, so I thought, sufficient to spark and sustain a productive discussion in an art history context. However, at the end of my presentation, and possibly as a means of igniting discussion within the student group, an art history lecturer ventured the opinion that the UK was awash with painters working in studios waiting to be discovered. Although a fleeting, if not flippant comment which would not find its way into print, the lecturer’s observation did represent for me a certain hostility within art history teaching towards asserting that the art world is a racially structured space. This personal experience took place within what could be considered a relatively liberal and progressive art history department. Nevertheless, it embodied, in microcosm, the formidable challenges and obstacles within art history. For the record, in 2000, at the age of 65, Bowling was not ‘waiting to be discovered’. His exemplary practice and the high regard in which he was held was reflected in many important exhibitions of his work in the UK and the US, which belied his systematic exclusion from the mainstream art world. In the intervening years, Bowling’s stock has risen significantly within the museum arena, yet art history teaches us nothing; despite a plethora of awards, exhibitions and critical attention, we are offered only a selective view of history. Tate’s foregrounding of Bowling’s time working alongside Hockney and Kitaj is a case in point. Scouring Tate: A History from 1998 by Frances Spalding reveals not a single mention of Bowling. Following Lubaina Himid being heralded as the oldest practitioner to win the coveted Turner Prize, the BBC glibly commented that ‘Himid made her name in the 1980s as one of the leaders of the British black arts movement – both painting and curating exhibitions of similarly overlooked artists’. Where Bowling is now seamlessly positioned as part of postwar British art, Himid’s recognition was framed by a casual acknowledgement of ‘similarly overlooked artists’. These seemingly different forms of historical recovery nullify rather than address the incalculable damage systematic art-world exclusions have had and continue to have both on individual practitioners and on wider narratives of art history.

Art historians and cultural theorists have offered insightful texts which could in many ways be considered as templates for reading and complicating conceptions of British art history. For example, Kobena Mercer’s essay ‘Ethnicity and Internationality: New British Art and Diaspora-Based Blackness’ from 2000, published in Third Text (whose founding editor was Araeen), considered ‘the curious position(s) of diaspora artists amidst the contradictory forces of art world globalisation and regressive localism’, thereby intervening to address the stranglehold yBas had on art history. Such important essays, however, remain at academia’s periphery.

The weighty monograph which accompanies Araeen’s retrospective synergises the museum and academia. The publication includes ten texts charting Araeen’s enduring and expansive career as an artist, curator, writer, publisher and editor. This formidable collection of essays by academics such as Michael Newman, Marcus du Sautoy, Zöe Sutherland, John Roberts and Courtney J Martin (who, interestingly, is also a contributor to Bowling’s monograph) leaves us with plenty to ponder, with titles such as ‘Third Text: Modernism and Negritude, and the Critique of Ethnicity’, ‘Dialectics of Modernity and Counter Modernity’ , ‘Politics of Symmetry’ and ‘Equality, Resistance, Hospitality: Abstraction and Universality in the Work of Rasheed Araeen’ and so on. Nick Aikens’s decision, as the publication’s editor, to primarily call on academics is in many respects in keeping with the conventions of such retrospective tomes. When considered in relation to academia, however, it does raise a question about what function this writing has as part of a wider commitment to challenging what Charles Esche describes in his preface to the monograph as ‘the partiality and blindness of Eurocentric modernism’. Is this writing on Araeen akin to an otherwise absent parent who lavishes copious birthday gifts on their child? The relative paucity of teaching within academia on postwar black artists does temper the critical triumphalism of Araeen’s monograph. The contributors’ biographies alone suggest that their essays here are, almost without exception, a break from their usual artists or areas of interest. Is there a correlation between the type of voices of authority who now champion excluded practitioners and the voices which previously ignored their exclusion?

Cultural theorists and art historians have contributed an immense range of scholarship, much of it academic, which has done much to expand and challenge received notions of art history. Three anthologies produced between 1999 and 2008 explored key themes spanning contemporary African art as an emerging force during the 1990s, the re-examination of art from the colonial period, and new discourses on modern and contemporary art. Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Market Place, 1999, edited by Olu Oguibe and Okwui Enwezor, pooled a wide range of articles from journals and exhibition catalogues published between 1991 and 1997, written by art historians, anthropologists and cultural theorists such as Kwame Anthony Appiah, Mercer, VY Mudimbe, Laura Mulvey, Everlyn Nicodemus, Chika Okeke and John Picton. Similarly, Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History, 2002, edited by Kymberly N Pinder, includes a broad collection of writing but this time using a narrower ‘historical lens’, primarily focusing on art from the 19th and 20th centuries but also including art from ‘antiquity to the middle ages, and Modernism and its “Primitive” Legacy’ in order to reconsider historical painting, through to the work of artists such as Sargent Johnson, Horace Pippin and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Then there is Annotating Art’s Histories: Cross-Cultural Perspectives in the Visual Arts 2005-08, co-published by MIT Press and edited by Mercer, which further exemplifies critical thinking emanating from academia. The first volume, Cosmopolitan Modernisms, 2005, offered what Mercer described as ‘a partial and provisional review of how we have arrived at the current state of play with regard to understanding cultural difference, not as an arbitrary irrelevance that detracts from the “essence” of art, nor as a social problem to be managed by compensatory policies, but as a distinctive feature of modern art and modernity that was always there and which is not going to go away’. Unlike the previous two anthologies, Mercer’s series was primarily based on new writing, but in keeping with their aspiration it too ‘sets out to question the depth of our historical understanding of cultural difference’. We could also cite art journals such as Third Text, Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art and Small Axe, launched in 1987, 1993 and 1997 respectively, which have also, to varying degrees, been supported by those based in the academic world. But why has this wealth of publishing been unable to have any impact on the presumed white authority which continues to underpin the teaching of art history? The histories of black artists were often considered as separate if not largely irrelevant to art history. Today, museums are historicising and incorporating black artists into British art history’s grand narrative; but does this now present a conundrum for art history departments? It is an understatement to suggest that those responsible for managing art history departments think more carefully about what constitute core subjects and specialisms in the 21st century. Artist Mary Evans’s eloquent observation that ‘the political, social, and cultural dynamics of modern Britain are in many respects the legacy of Britain’s imperial past’ provides an enticing starting point for narrating postwar British art. Rather than being seen as limited or specialist, though, such an approach to art history should be seen as a challenge to existing conventions. This is not a new proposition.

Art historians and cultural critics have for decades challenged the formidable orthodoxies on which art history has prevailed and been taught. Art historian Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking essay ‘Why Are There No Great Women Artists’, 1971, and John Berger’s seminal television series and book Ways of Seeing, 1972, both exploded myths about the production, dissemination and interpretation of art. Exposing the gendered and socially stratified but unspoken narratives which governed art history, Nochlin and Berger brought not only new readings to the canon, but they also by necessity explicitly critiqued the epistemologies of art history. Influenced by this work, art historian Griselda Pollock recently noted in an updated preface to Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, 1981, which she co-authored with Rozsika Parker, that a book ‘merely trying to add back the missing names of women was doomed to failure’. Instead, it proposed a critique of the structural sexism in the discipline of art history itself. Such critical approaches are integral to art history teaching. Peggy Phelan’s Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, 1993, and Amelia Jones’s Body Art: Performing the Subject, 1998, were staple texts within my History of Art MA. In different ways, both went beyond merely arguing for representation within the canon to disrupting its convention (for Jones, it was ‘the particular potential of body art to destabilise the structures of conventional art history and art criticism’). In this context, is it possible to understand the limitations of historical revisionism as a means of upholding convention?

In ‘The Difficulties of Naming White Things’, 2012, Eddie Chambers offers a series of cogent observations about the often-unspoken conventions which are hidden in plain sight but permeate art history and academia. He expresses the ‘frustration of not being able to call what generally passes as art history white art history, even though, with its consistent omissions and partial accounts, that is what the universities of the country are by and large serving up within their art history departments’. Beyond what Griselda Pollock termed as challenging art history’s ‘structural sexism’, Chambers identifies what he considers to be ‘an uncomfortable and frequently unacknowledged racialised schism within art history and academia’. In the US some discipline areas are now habitually demarcated along racial lines, such as ‘African Americanist’, ‘Africanist art’, ‘African diasporaists’. In the UK, academe’s gravitation towards courses such as ‘global perspectives’ or ‘non-Western art’ may represent concessions to notions of inclusivity and diversity but, equally, these euphemistic and all-encompassing terms also serve to reinforce racial hierarchies within art history.

Keeping difference at arm’s length and maintaining the unspoken but explicit racial stratification within academia supports the status quo. This is an unsatisfactory situation not aided by the disparity between the number of white and black academics across the range of the UK’s universities, which is striking. Employment statistics paint a bleak picture. In 2011, it was reported in the Guardian that 50 out of 14,000 British professors were black, while in 2016/17, 25 black women and 90 black men could be counted among 19,000 professors. In Inside the Ivory Tower: Narratives of women of colour surviving and thriving in British academia, Deborah Gabriel describes this situation as reflecting the unspoken ‘white privilege’ which pervades academia and plays a critical role in perpetuating inequality. The situation is all the more perverse when considered against the significant numbers of black artists who have received honorary degrees from universities wanting to be seen to be progressive.

Today, marketing strategies and campaigns used by universities are key for the recruitment of fee-paying students. These promotional and often formulaic campaigns, across the sector, project university life as enjoyable, aspirational and inclusive. Perusing the plethora of university websites it is noticeable how prominent black people have become in this marketing. Conversely, delve a little deeper into these university websites and their academic departments, and black people are often conspicuous by their absence. While statistics testify to enduring inequality, in today’s market-driven educational economy the absence of black faculty carries even greater significance. Pursuing a career in academia is by no means the only purpose of a university education, yet, on current evidence, and despite the increase in numbers of black and Asian people receiving degrees, it seems that a sector eager to educate these students remains less inclined to employ them. Such realities temper the current university fad for advertising employment success rates of graduates.

The racialised employment practices of universities raise questions about the veracity and the purpose of equality statements and equal opportunity monitoring forms. Beyond liberal posturing, what purpose do such bureaucratic mechanisms serve? Racial inequality is an issue across academia but is there an area where it remains more pronounced than in the privileged world of art history? Women have undoubtedly fought hard to prosper here but, with few exceptions, art history departments remain as white today as they were 30 or 40 years ago. Is this responsible for black British scholars seeking opportunities in the US? Despite the critical triumphalism which underpins Bowling and Araeen’s retrospectives, day-to-day teaching of art history appears impervious to the changes proposed by the very scholarship it is producing. Clearly, what is needed is a more sustained engagement with a wider body of black artists’ histories. Equally, diversifying the curriculum needs to be supported by more sustained efforts to decolonise academia.

Richard Hylton is a writer and researcher based in London.

First published in Art Monthly 426: May 2019.

0 notes