#Hilma af Klint - Svanen (1914)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hilma af Klint - Svanen (1914)

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Svanen’ by Hilma af Klint, c. 1914.

#hilma af klint#vintage art#classic art#art#art history#old art#art details#vintage#painting#moody art#oil painting#swan

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

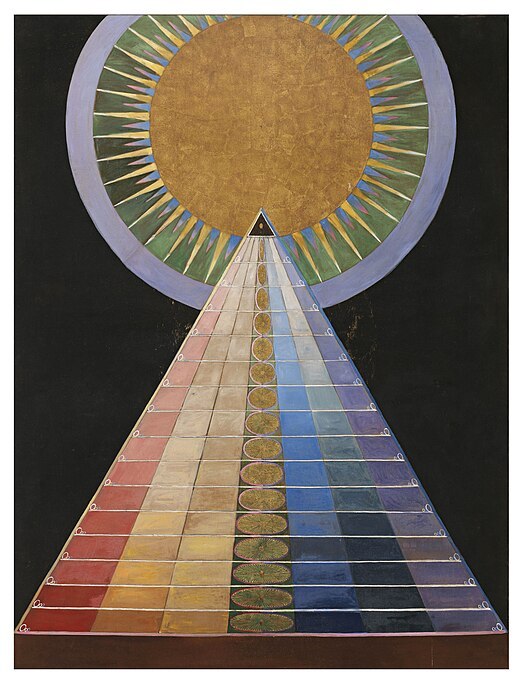

Descubriendo el místico arte de Hilma af Klint

Group IX/SUV, The Swan, 1915

Esta artista es parte de la larga lista de creadores de los que me he enamorado durante el último año por el hecho de que su obra toca una parte de mí que siempre he tenido el interés de empezar a explorar.

Muchísimos nombres han brillado durante los últimos siglos, artistas cuyas historias son tan misteriosas como sus obras. Uno de estos nombres es el de Hilma af Klint, una artista sueca nacida en 1862, cuyas obras cargadas de misticismo se consideran las primeras obras del movimiento abstracto en la historia del arte.

Una buena cantidad de sus trabajos existe incluso antes de las composiciones de Kandinsky, Malevich y Mondrian.

También perteneció a un grupo llamado Las Cinco, un círculo de mujeres inspiradas en la teosofía, que compartían la creencia de la importancia de intentar contectar con los llamados "Altos Maestros", generalmente a través de sesiones de espiritismo. Sus pinturas, que a veces parecen diagramas, eran una representación visual de complejas ideas espirituales.

Las pinturas convencionales de la artista se convirtieron en su fuente de ingresos económicos, pero lo que para ella era el "Gran Trabajo", realizado durante su vida, siguió siendo una actividad separada. Sólo las audiencias espiritualmente interesadas tenían algún conocimiento de este conjunto de obras y no fueron exhibidas al público hasta muchos años después de su muerte. Los comentarios en sus cuadernos indican que sentía que el mundo no estaba del todo preparado para el mensaje que pretendían comunicar.

En el año 1880, murió su hermana menor Hermina y fue en ese momento cuando empezó a desarrollarse su conexión con lo esprititual.

Para el año 1887, se graduó con honores de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Estocolmo y se estableció allí como una artista respetada, expuso pinturas figurativas y se desempeñó brevemente como secretaria de la Asociación de Mujeres Artistas Suecas.

Su interés por la abstracción y el simbolismo surgió de la implicación de Hilma af Klint en el espiritismo, muy en boga a finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX. Sus experimentos en investigación espiritual comenzaron en 1879. Ya desde muy joven se involucró en el espiritismo. Posteriormente le siguió un gran interés por las ideas del rosacrucismo, la teosofía y la antroposofía.

Svanen (El cisne), 1914-1915

Algo muy interesante de su trabajo con el grupo "las Cinco", fue que ella experimentaba mucho con una técnica llamada dibujo automático, lo que la llevó a crear un lenguaje geométrico capaz de conceptualziar fuerzas invisibles.

Mediante este trabajo exploró las religiones del mundo, átomos y el mundo vegetal.

Del contacto con los Grandes Maestros surge una serie de obras llamadas "Pinturas para el templo" (algunas presentes en este post); sin embargo, ella nunca entendió a qué se refería este "Templo". Estas obras fueron realizadas entre 1906 y 1915, llevadas a cabo en dos fases con una interrupción entre 1908 y 1912. Cuando Af Klint descubrió su nueva forma de expresión visual, desarrolló un nuevo lenguaje artístico. Su pintura se volvió más autónoma y más intencional. Lo espiritual seguiría siendo la principal fuente de creatividad durante el resto de su vida.

Luego de finalizar las obras del templo, terminó la guía espiritual pero siguió su trabajo como pintora abstracta, independiente de influencias externas.

A lo largo de su vida, Hilma af Klint buscaría comprender los misterios con los que había entrado en contacto a través de su trabajo. Produjo más de 150 cuadernos con sus pensamientos y estudios.

Aquí otra serie de obras de la artista:

Grupo IX/SUW, El cisne, n.º 7 , 1915

The Swan, No. 18, Group IX/SUW, 1914-1915

Lo que un ser humano es, 1915

#hilma af klint#abstract art#abstraction#artist biography#lunas de alma#historia del arte moderno#modern art#historia del arte#arte moderno#featured

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Svanen, 1914, Hilma af Klint (1862-1944).

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Svanen (The Swan) No. 17, Group IX, Series SUW,1914-1915by Hilma Af Klint

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Episode 40: Hilma AF Klint

1. Hilma af Klint at the Royal Academy of Arts, Stockholm, 1885.

2. Hilma af Klint, The Swan No. 1, 1915.

3. Hilma af Klint, Parsifal Series No. 1, 1916.

4. Hilma af Klint, Altarpiece, No. 1, Group X, 1907.

5. Hilma af Klint, Svanen (The Swan) No. 17, Group IX:SUW, The SUW:UW Series, 1914-1915.

6. Hilma af Klint, Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth, 1907.

Listen to Full Episode Here

Subscribe on iTunes

#sources#hilma af klint#art history babes#art podcast#abstract art#abstract expressionism#spiritism#mysticism#spiritualism#ghosts#19th Century#20th Century#podcast

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hilma af Klint, Svanen (The Swan) No. 17, Group IX/SUW, The SUW/UW Series, 1914-1915. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-first-abstract-artwork

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Svanen (The Swan) Hilma af Klint 1914/15

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944, Stockholm)

Svanen (The Swan) No. 17, Group IX/SUW, The SUW/UW Series, 1914-1915.

via: Artsy

431 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Svanen

Hilma af Klint

1914

161 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Svanen (The Swan) No. 17, Group IX/SUW - Hilma af Klint

1914-1915

0 notes