#He could also be dark because of his West African ancestry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Honestly having parents with Afro-Asian genes (predominantly Asian) is fucking crazy cause yesterday I passed as Indian and the day before that I look so coloured (coloured is a racial classification in South Africa) which means I looked "mixed" or biracial at the very least.

At least I'm really interesting😭

#My mom (hate that lady) could pass as Japanese when her hair is straight#But her father was so Khoi it wasn't even funny#My dad could be dark cause his mom was half Indian.#He could also be dark because of his West African ancestry#Who knows

0 notes

Text

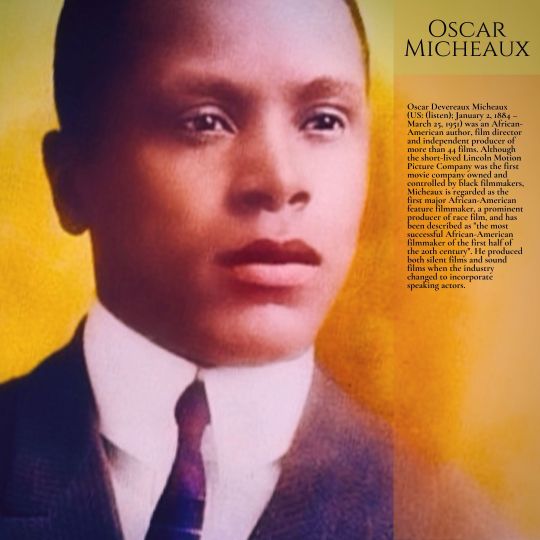

Oscar Micheaux

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (US: (listen); January 2, 1884 – March 25, 1951) was an African-American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and controlled by black filmmakers, Micheaux is regarded as the first major African-American feature filmmaker, a prominent producer of race film, and has been described as "the most successful African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century". He produced both silent films and sound films when the industry changed to incorporate speaking actors.

Early life and education

Micheaux was born on a farm in Metropolis, Illinois, on January 2, 1884. He was the fifth child born to Calvin S. and Belle Michaux, who had a total of 13 children. In his later years, Micheaux added an "e" to his last name. His father was born a slave in Kentucky. Because of his surname, his father's family appears to have been owned by French-descended settlers. French Huguenot refugees had settled in Virginia in 1700; their descendants took slaves west when they migrated into Kentucky after the American Revolutionary War.

In his later years, Micheaux wrote about the social oppression he experienced as a young boy. His parents moved to the city so that the children could receive a better education. Micheaux attended a well-established school for several years before the family eventually ran into money troubles and were forced to return to the farm. The discontented Micheaux became rebellious and his struggles caused problems within his family. His father was not happy with him and sent him away to do marketing in the city. Micheaux found pleasure in this job because he was able to speak to many new people and learned social skills that he would later reflect in his films.

When Micheaux was 17 years old, he moved to Chicago to live with his older brother, then working as a waiter. Micheaux became dissatisfied with what he viewed as his brother's way of living "the good life". He rented his own place and found work in the stockyards, which he found difficult. He moved from the stockyards to the steel mills, holding down many different jobs.

After being "swindled out of two dollars" by an employment agency, Micheaux decided to become his own boss. His first business was a shoeshine stand, which he set up at a wealthy African American barbershop, away from Chicago competition. He learned the basic strategies of business and started to save money. He became a Pullman porter on the major railroads, at that time considered prestigious employment for African Americans because it was relatively stable, well paid, and secure, and it enabled travel and interaction with new people. This job was an informal education for Micheaux. He profited financially, and also gained contacts and knowledge about the world through traveling as well as a greater understanding for business. When he left the position, he had seen much of the United States, had a couple of thousand dollars saved in his bank account, and had made a number of connections with wealthy white people who helped his future endeavors.

Micheaux moved to Gregory County, South Dakota, where he bought land and worked as a homesteader. This experience inspired his first novels and films. His neighbors on the frontier were predominately blue collar whites. "Some recall that [Micheaux] rarely sat at a table with his blue collar white neighbors." Micheaux's years as a homesteader allowed him to learn more about human relations and farming. While farming, Micheaux wrote articles and submitted them to the press. The Chicago Defender published one of his earliest articles.

Marriage and family

In South Dakota, Micheaux married Orlean McCracken. Her family proved to be complex and burdensome for Micheaux. Unhappy with their living arrangements, Orlean felt that Micheaux did not pay enough attention to her. She gave birth while he was away on business, and was reported to have emptied their bank accounts and fled. Orlean's father sold Micheaux's property and took the money from the sale. After his return, Micheaux tried unsuccessfully to get Orlean and his property back.

Writing and film career

Micheaux decided to concentrate on writing and, eventually, filmmaking, a new industry. He wrote seven novels. In 1913, 1,000 copies of his first book, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer, were printed. He published the book anonymously, for unknown reasons. Based on his experiences as a homesteader and the failure of his first marriage, it was largely autobiographical. Although character names have been changed, the protagonist is named Oscar Devereaux. His theme was about African Americans realizing their potential and succeeding in areas where they had not felt they could. The book outlines the difference between city lifestyles of Negroes and the life he decided to lead as a lone Negro out on the far West as a pioneer. He discusses the culture of doers who want to accomplish and those who see themselves as victims of injustice and hopelessness and who do not want to try to succeed, but instead like to pretend to be successful while living the city lifestyle in poverty. He had become frustrated with getting some members of his race to populate the frontier and make something of themselves, with real work and property investment. He wrote over 100 letters to fellow Negroes in the East beckoning them to come West, but only his older brother eventually took his advice. One of Micheaux's fundamental beliefs was that hard work and enterprise would make any person rise to respect and prominence no matter his or her race.

In 1918, his novel The Homesteader, dedicated to Booker T. Washington, attracted the attention of George Johnson, the manager of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company in Los Angeles. After Johnson offered to make The Homesteader into a new feature film, negotiations and paperwork became inharmonious. Micheaux wanted to be directly involved in the adaptation of his book as a movie, but Johnson resisted and never produced the film.

Instead, Micheaux founded the Micheaux Film & Book Company of Sioux City in Chicago; its first project was the production of The Homesteader as a feature film. Micheaux had a major career as a film producer and director: He produced over 40 films, which drew audiences throughout the U.S. as well as internationally. Micheaux contacted wealthy academic connections from his earlier career as a porter, and sold stock for his company at $75 to $100 a share. Micheaux hired actors and actresses and decided to have the premiere in Chicago. The film and Micheaux received high praise from film critics. One article credited Micheaux with "a historic breakthrough, a creditable, dignified achievement". Some members of the Chicago clergy criticized the film as libelous. The Homesteader became known as Micheaux's breakout film; it helped him become widely known as a writer and a filmmaker.

In addition to writing and directing his own films, Micheaux also adapted the works of different writers for his silent pictures. Many of his films were open, blunt and thought-provoking regarding certain racial issues of that time. He once commented: "It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights." Financial hardships during the Great Depression eventually made it impossible for Micheaux to keep producing films, and he returned to writing.

Films

Micheaux's first novel The Conquest was adapted to film and re-titled The Homesteader. This film, which met with critical and commercial success, was released in 1919. It revolves around a man named Jean Baptiste, called the Homesteader, who falls in love with many white women but resists marrying one out of his loyalty to his race. Baptiste sacrifices love to be a key symbol for his fellow African Americans. He looks for love among his own people and marries an African-American woman. Relations between them deteriorate. Eventually, Baptiste is not allowed to see his wife. She kills her father for keeping them apart and commits suicide. Baptiste is accused of the crime, but is ultimately cleared. An old love helps him through his troubles. After he learns that she is a mulatto and thus part African, they marry. This film deals extensively with race relationships.

Micheaux's second silent film was Within Our Gates, produced in 1920. Although sometimes considered his response to the film Birth of a Nation, Micheaux said that he created it independently as a response to the widespread social instability following World War I. Within Our Gates revolved around the main character, Sylvia Landry, a mixed-race school teacher. In a flashback, Sylvia is shown growing up as the adopted daughter of a sharecropper. When her father confronts their white landlord over money, a fight ensues. The landlord is shot by another white man, but Sylvia's adoptive father is accused and lynched with her adoptive mother.

Sylvia is almost raped by the landowner's brother but discovers that he is her biological father. Micheaux always depicts African Americans as being serious and reaching for higher education. Before the flashback scene, we see that Sylvia travels to Boston, seeking funding for her school, which serves black children. They are underserved by the segregated society. On her journey, she is hit by the car of a rich white woman. Learning about Landry's cause, the woman decides to give her school $50,000.

In the film, Micheaux depicts educated and professional people in black society as light-skinned, representing the elite status of some of the mixed-race people who comprised the majority of African Americans free before the Civil War. Poor people are represented as dark-skinned and with more undiluted African ancestry. Mixed-race people also feature as some of the villains. The film is set within the Jim Crow era. It contrasted the experiences for African Americans who stayed in rural areas and others who had migrated to cities and become urbanized. Micheaux explored the suffering of African Americans in the present day, without explaining how the situation arose in history. Some feared that this film would cause even more unrest within society, and others believed it would open the public's eyes to the unjust treatment of blacks by whites. Protests against the film continued until the day it was released. Because of its controversial status, the film was banned from some theaters.

Micheaux adapted two works by Charles W. Chesnutt, which he released under their original titles: The Conjure Woman (1926) and The House Behind the Cedars (1927). The latter, which dealt with issues of mixed race and passing, created so much controversy when reviewed by the Film Board of Virginia that he was forced to make cuts to have it shown. He remade this story as a sound film in 1932, releasing it with the title Veiled Aristocrats. The silent version of the film is believed to have been lost.

Themes

Micheaux's films were made during a time of great change in the African-American community. His films featured contemporary black life. He dealt with racial relationships between blacks and whites, and the challenges for blacks when trying to achieve success in the larger society. His films were used to oppose and discuss the racial injustice that African Americans received. Topics such as lynching, job discrimination, rape, mob violence, and economic exploitation were depicted in his films. These films also reflect his ideologies and autobiographical experiences.

Micheaux sought to create films that would counter white portrayals of African Americans, which tended to emphasize inferior stereotypes. He created complex characters of different classes. His films questioned the value system of both African-American and white communities as well as caused problems with the press and state censors.

Style

Critic Barbara Lupack described Micheaux as pursuing moderation with his films and creating a "middle-class cinema". His works were designed to appeal to both middle- and lower-class audiences.

Micheaux said,

My results ... might have been narrow at times, due perhaps to certain limited situations, which I endeavored to portray, but in those limited situations, the truth was the predominate characteristic. It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights. I am too imbued with the spirit of Booker T. Washington to engraft false virtues upon ourselves, to make ourselves that which we are not.

Death

Micheaux died on March 25, 1951, in Charlotte, North Carolina, of heart failure. He is buried in Great Bend Cemetery in Great Bend, Kansas, the home of his youth. His gravestone reads: "A man ahead of his time".

Legacy and honors

The Oscar Micheaux Society at Duke University continues to honor his work and educate about his legacy.

1987, Micheaux was recognized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

1989 the Directors Guild of America honored Micheaux with a Golden Jubilee Special Award.

The Producers Guild of America created an annual award in his name.

In 1989, the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame gave him a posthumous award.

Gregory, South Dakota holds an annual Oscar Micheaux Film Festival.

In 2001 Oscar Micheaux Golden Anniversary Festival (March 24–25) Great Bend, Kansas

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Oscar Micheaux on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

On June 22, 2010, the US Postal Service issued a 44-cent, Oscar Micheaux commemorative stamp.

In 2011, the Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia created a category for donors, the Micheaux Society, in honor of Micheaux.

Midnight Ramble: Oscar Micheaux and the Story of Race Movies (1994) is a documentary whose title refers to the early 20th-century practice of some segregated cinemas of screening films for African-American audiences only at matinees and midnight. The documentary was produced by Pamela Thomas, directed by Pearl Bowser and Bestor Cram, and written by Clyde Taylor. It was first aired on the PBS show The American Experience in 1994, and released in 2004.

In 2019, Micheaux's film Body and Soul was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

The Oscar Micheaux Award for excellence was established.

The Czar of Black Hollywood

In 2014, Block Starz Music Television released The Czar of Black Hollywood, a documentary film chronicling the early life and career of Oscar Micheaux using Library of Congress archived footage, photos, illustrations and vintage music. The film was announced by American radio host Tom Joyner on his nationally syndicated program, The Tom Joyner Morning Show, as part of a "Little Known Black History Fact" on Micheaux. In an interview with The Washington Times, filmmaker Bayer Mack said he read the 2007 biography Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only by Patrick McGilligan and was inspired to produce The Czar of Black Hollywood because Micheaux's life mirrored his own. Mack told The Huffington Post he was shocked that, in spite of Micheaux's historical significance, there was "virtually nothing out there about [his] life". The film's executive producer, Frances Presley Rice, told the Sun Sentinel that Micheaux was the first "indie movie producer." In 2018, Mack was interviewed by the news site Mic for its "Black Monuments Project", which named Oscar Micheaux as one of its 50 African-Americans deserving of a statue. He said Micheaux embodied "the best of what we all are as Americans" and that the filmmaker was "an inspiration."

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’ll Do You One Better--What House is Gamora?!

Summary: Gamora is from a race of Egyptian snake-women, that was massacred by the Titan Thanos. She carries the legacy of Salazar Slytherin wherever she goes, often literally.

House: Slytherin

Species: Wadjet (Egyptian snake women)

Wand: Cypress, 14 inches, Sphinx hair

Broom: Custom made, with two tails; able to power through weather most brooms would shatter in

Other effects: The Sword of Salazar Slytherin, which she often stores in her broom

Patronus: Python

Specialties: Dark Arts

Groomed for Slytherin

Gamora has the traits of both Gryffindor and Slytherin down to a T, and by a happy coincidence, her skin and hair reflect the colors of both houses. It really was a close call.

Standing up to a giant whose army just massacred your homeland takes balls for anyone, especially a child. That was a pretty damn Gryffindor thing to do. But Thanos decided to adopt Gamora for the Slytherin traits he sensed in her. He hand-picked all of his children for the same reason, but Gamora had an ambition, cunning and stubbornness that blew the others out of the water. Taking her aside, so she wouldn't see the massacre of her people, he showed her a tattered old green hat, once worn by Salazar Slytherin, and told her to reach inside. The green child pulled out the Sword of Slytherin faster and more smoothly than any of his previous "children" had before. That was when Thanos decided Gamora was his favorite daughter.

Thanos "adopted" (kidnapped and brainwashed) Gamora, and applied the the most extreme versions of the traits of Slytherin House in her upbringing. He taught her to be cold and calculating, mercilessly cunning, and to stop at nothing to achieve her goals. He used the Cruciatus Curse as both discipline and to "build character" in all his children, and pitted Gamora against her adopted sister Nebula.

Her Slytherin traits of self-preservation and determination were more apparent than her Gryffindor courage and chivalry, in that it took years for her to finally realize how evil her "father" was and disobey him. And it never even occurred to her to think about what every fight did to her adoptive sister Nebula, because she was so focused on her own survival. But Gamora eventually learned to retool her Slytherin traits to blend with her Gryffindor heroism, and broke free of Thanos.

Wherever she went, Gamora was judged as a "villain" before she even did anything, simply because of her connection to Thanos and her House. Not only did she prove herself a hero, Gamora wound up being the most tempered, wise, and noble member of Peter Quill's crew. It was usually she, with her Slytherin pragmatism, tempering Quills Gryffindor rashness, in the relationship. (The whole crew learned their Houses while visiting the Collector, who temporarily had possession of Hogwarts' Sorting Hat.)

Gamora was courageous and chivalrous, but there's a reason Peter Quill was the Gryffindor and she was not. When the time finally came, Peter was willing to kill Gamora to stop Thanos, as she'd requested of him. But hypocritically, Gamora was not willing to do the same when it was a choice between her sister Nebula and the Soul Stone.

Gamora's worst fear was dying alone with only her evil "father" near her, and by a cruel irony, that was not only exactly what happened, but it was all for the sake of Salazar's legacy. Each of the Infinity Stones had been hidden by a powerful wizard throughout history (Merlin had the Time Stone, obviously). Salazar Slytherin had surrounded the Soul Stone with an incredibly dark curse, testing the seeker's ambition, forcing them to sacrifice the person they loved most to obtain it. On the ruins of Salazar's home castle, where the Stone was hidden, Gamora tried to commit suicide with Salazar's sword before Thanos could kill her to obtain the stone; but using the Reality Stone, he turned the Sword of Slytherin into bubbles. Then he tossed her off the tower, and obtained the Soul Stone.

To Thanos's surprise, the Sword of Slytherin returned in the later battle at Hogwarts, when Tony Stark pulled it from the Sorting Hat. But that is another story entirely.

For My Real Parents

Through a combination of Time Travel and Priorie Incantatem, Gamora returned both in spirit and body. While Tony Stark dusted Thanos’s minions, the Titan resisted the spell, until two Gamoras jumped him: one, the ghost of the “daughter” he’d murdered, that had emerged when Thanos and Tony’s Infinity Wands had clashed; and the other, a version of Gamora from the past, that followed Nebula back to the present-day.

Past-Gamora stabs Thanos through the heart with the Sword of Slytherin, and says just loud enough for him to hear, “For my real parents.” Before he dies, Thanos sees himself in a field, facing a young Gamora, the child he orphaned and kidnapped all those years ago. “You love nothing,” the green child says locking eyes with him. “And so you have nothing. You are nothing.” She, the field, and Thanos’s entire universe disintegrate, as the Titan crumbles into a pile of ash. You Promised When the dust settles, there is only one Gamora. The Infinity-Ghost has merged with the past body. She shakily rises to her feet, tears falling down her green face. “Gamora!” Peter Quill, who hasn’t had a chance to speak to her yet, tears across the field to her. For a moment, it looks like they’re about to kiss. Gamora chokes, “Peter…” and then knees him in the balls. She finishes with a hiss, “You promised!” Clutching his shattered bludgers, Quill retorts in a strained voice, “Hypocrite!” He is referring to the fact that Gamora couldn’t sacrifice her sister to keep the Stone from Thanos. Gamora makes an admitting face, helps him up, and now they kiss.

Species:

FACT: In Ancient Egypt, Muggles living in the city of Dep worshiped a local snake goddess named Wadjet. (Source: real history.) In fact, the Wadjet were a whole magical race of reptilian snake-like women. (Source: my ass.)

These were Gamora's people. They resembled reptilian humanoids, and were often considered the better-looking cousins of Goblins. As a Wadjet, Gamora has enhanced strength, durability, speed and senses. Harry Potter didn't learn much about the Wadjet at Hogwarts, because their society was on the brink of collapse by that time. Thanos "saved" them by killing off half the population. He considered it a testament to his "fairness" that he made no exception for the race held in high regard by his ancestor and idol, Salazar Slytherin.

Naturally, Peter Quill--lacking in any education, Magical or Muggle--had never heard of the Wadjet. Gamora was confused when he asked if she was related to the Wicked Witch of the West. She didn't understand why she should fear a house falling on her, or why she would need the protection of glittering shoes when she already had a dragonhide coat armed with several protective charms. Wand: "Wands of cypress find their soul mates among the brave, the bold and the self-sacrificing: those who are unafraid to confront the shadows in their own and others’ natures." (harrypotter.wikia.com/wiki/Cyp…) Remus Lupin's wand was a Cypress. The sphinx hair may seem like an odd choice, with Gamora not particularly specializing on riddles or puzzles. But sphinxes are overall associated with wisdom and ferocity, both of which describe Gamora. And of course, the Sphinx is from the same part of the world she is. Patronus:

Pythons are "ambush predators," fitting for Gamora. Naturally, Quill took one look at her Patronus and dubbed it "Monty." Monty Python, he explained, was the name of a band of Human minstrels, from around the same era as the hero Kevin Bacon. Pythons are adaptable snakes, that can make their homes in a variety of environments, as long as they are left to their own devices, as they are solitary animals. They are agile, and some species are able get up into trees. (www.livescience.com/53785-pyth…)

AN: Gamora was hard to sort. Like so many others, I made the decision based on her dynamic with other characters. And the Slytherin legacy worked so well into her story, that I had to use it. While the Egyptian connection was partially a homage to her actress Zoe Saldana, who has African ancestry, it was also inspired by her eye-shadow and cyborg facial markings, which have a vaguely Egyptian look to them.

#gamora#sytherin#hogwarts house#guardians of the galaxy#marvel#avengers#potterverse#sword of slytherin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okie dokie, a long post about Commodities. This is not rigorous scholarship, history is not my field, I knew nothing about this subject before, really. It’s just a quick google. So, without further ado.

“Well, there was this one time I dropped anchor near a small island called Gorée…”

Gorée Island is a small island off the coast of Senegal which played a part in the transatlantic slave trade. The House of Slaves and the Door of No Return, now a museum and UNESCO World Heritage Site, was built in the 18th century. There are so many different estimations of how many people passed through Gorée and different analyses on how important it was to the trade. However, it is important now, and now is when the series was made. It’s a name that carries connotations of not only the lives directly affected by the slave trade then but the continuing repercussions that we’re still seeing and still understanding. There’s an annual festival, “a way to use art and culture to remember [the sad page in history] and to unite the island's diaspora… it is not enough to remember the past, but that it must be used to build a better future in which communities can grow closer to eliminate all forms of discrimination”, (Augustin Senghor, the mayor of Gorée Island, speaking in 2010 about the festival). The Facebook page for the festival says

“Le Gorée Diaspora Festival est un ciment fédérateur entre la Communauté Sénégalaise à travers Gorée et l’ensemble des visages et voix de la diaspora Africaine s’engageant à « rectifier voire inverser les conséquences négatives de l’esclavage et du lourd tribu payé par le continent noir et ses enfants sous le vocable de Renaissance Africaine qui englobe la notion de Développement que l’Afrique n’a pu connaître du fait, justement, de l’esclavage”

I don’t speak French but I can translate a little… the Gorée Diaspora festival is… something about unifying the Senegalese communities through different voices…. Something about reversing and counteracting the consequences of the slave trade, something about a heavy tribute (price?) paid by the ‘children’ of the continent and the diaspora, and includes ideas about the development that Africa could not know because of the slave trade. My dudes, je ne parle pas Francais, so do correct me or translate better.

The Gorée Institute promotes culture and arts in Africa and in 2015 (I think) they ran a poetry residency on the island that aimed “to reignite a literary tradition that has begun to fade, and to help promote arts, culture, and freedom of expression as intrinsically effective methods of fostering open societies in the region”

How to Fall in Love with an African City

by Gbenga Adesina, a 24-year-old poet from Nigeria

In time, you too will come to learn dear friend, the soft rustle,

Soft whoosh of affection for a city like a lover like a love song: Nairobi, Abuja, Dakar

throbbing in your ribs: Accra, Harare, Port Novo, carving a place for themselves, to nestle

In spite of yourself in the jar

of things you call loved.

I know eyes have their own memories and fears

and you come here seeking only the darkness you’ve been

promised. But come again to Abidjan friend, come to Yamoussoukro, come

to Kigali, to Luanda, to Lagos, where the city vowels sing to you, sing to you.

Sidewalks that are nations on their own. Yellow buses that write you into a story

Wi-Fi spots and shopping malls and smiles that warm your arms and strangers that become

friends in an instant. Grilled meats that introduce your tongue to you.

In time, you too will come to learn dear friend, the soft rustle, soft

Whoosh of affection for a city like a lover like a love song: Nairobi, Abuja, Kigali,

Dakar throbbing in your ribs. What it means for a city to hold you by the hands

and love you and lead you to places you’ve never been inside yourself

again and again at the junction of laughter.

Ok. So, these are a few facts I’ve come up with after a quick Google around, and a few things that are coming out of Gorée today. Back to the series, Bonnaire name drops an island that would have already been involved in the slave trade in the 17th century. The thing about the transatlantic trade was that even when not trading people, trade was deeply involved in slaving. The transatlantic triangle meant that cargo was being shipped to pay for slaves and nurture ties in Africa and supply the colonial settlements, a cargo of people was then shipped to the Americas, then the produce of the Americas was shipped to Europe. Paul Munier, as a trader, was as implicated in the trade as Bonnaire, just a different side of the triangle. His cargo might not have been people, but it would have been from the Americas and in all probability produced by the people taken on Bonnaire’s slave ships. The name-drop, then, is suggestive of the slave trade and brings up a whole host of connotations and connections.

I suppose it was probably put in to suggest to an audience that Bonnaire is a slaver, as a ‘clue’. I think it works beyond that, though. It is also, because of what the island is now, suggestive of a diaspora, and the series brings in Samara, and Porthos, people who are perhaps part of a diaspora (I am not naming Sylvie because her story never brushes on her… what is it Bonnaire calls it? Ah. Here we go: “ancestry”). I don’t know what else is within that allusion, probably many things, but I just wanted to pick up the casual reference and think about it.

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/goree-island-home-door-no-return (basic info about the island from an American site. I looked at a lot of sources but this seems the most straightforward)

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/19/world/africa/19ndiaye.html (an article about Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye, curator of the House of Slaves, from 2009 after he died)

https://www.voanews.com/a/goree-island-festival-celebrates-african-diversity-107230813/130315.html (quote from Augustin Senghor)

https://www.facebook.com/pg/GoreeDiasporaFestival/about/?ref=page_internal (facebook ‘about’ page)

www.goreeinstitut.org (Gorée Institure’s page, in French)

https://afrolegends.com/2016/07/27/reclaiming-african-history-goree-and-the-slave-trade-in-senegal/ (another page about Gorée and reclamation)

“A calabash. Grows all over West Africa.”

I just want to quickly pick up on this allusion, mostly because it is used to make musical instruments and you know, I like music. So. I’m just gonna share a couple of things I found. The first is a page from RCIP-CHIN [a Canadian… it’s in French again, CHIN stands for Canadian Heritage Information Network, it’s a heritage site basically I think], a teaching page aimed at children about traditional calabash objects from Senegal, so stuff made from calabash, from a region that we know Bonnaire visited.

http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitLo.do?method=preview&lang=EN&id=10659

The Kora is an instrument made from the calabash, so here are two videos of kora music,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEoMz79NT60 I don’t know this one I got it by googling, it’s called ‘KORA TRIO SENEGAL Konzert Rote Fabrik Zürich’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ig91Z0-rBfo this one is Sona Jobarteh and band, it says it’s music from West Africa.

Also just a thing from a quick google, A Drunken Ode on an Ashanti Calabash, based on Keats’ Ode to a Grecian Urn, because, you know, how awesome is that?

You bald head crackpot of an unworshipped gourd

Owner of sweet whine, lined with alternate this chord

What incense wafts incessant on your inside

What merry joys accompany your company.

What brave brow, what bold curve

Hairless rim-head, competitor of shaved eggshells

Afraid to touch the earth but on your belly.

Glass wine is sweet, but gourd wine is sweeter

Funeral wine, party wine, you hold them better

What a roll you make on your underbelly

When rocking here this way and that

What browned fare, what fair brow

What endless, gaping gap on your inside

Forever open to wine and air.

Pour me a drink, pour me two

Which are sipped ‘pon suppers supped

Momentous joy for a dugout unleaked

What thin wall, what thick skin

What strong ethers of spirits reek

Shanty half body of insipid taste.

Sleeping is truth, and truth sleeping

Let me now lie and tomorrow waste

https://afrilingual.wordpress.com/2013/11/28/drunken-ode-on-an-ashanti-calabash/

“A bottle of rumbullion. The colonists make it out of sugar molasses, so potent they call it kill devil”

Last allusion I’m picking up, I swear, and again I’ll be quick about it. John J. McCusker says that “rum and molasses early became strategic items in the vital trade with the West Indies, being readily available and readily acceptable returns for colonial goods shipped there. The distilling of rum from molasses created a substantial colonial industry, employing local capital, management skills, and labor[sic]”. Bonnaire’s rum is again just an indication of both his trade and the deeper implications. Rum is a ‘commodity’ (a word McCusker uses over and over that I can’t hear without wincing anymore) that was used substantially in the transantlantic trade. Again, the commodities and luxuries that Bonnaire is shipping, his cargo, is all implicated in the slave trade and, again, I want to point out Paul Munier as a trader who might not actively be a slaver but is still part of the slave trade.

The Rum Trade and the Balance of Payments of the Thirteen Continental Colonies, 1650-1775

Author(s): John J. McCusker

Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 30, No. 1, The Tasks of Economic History(Mar., 1970), pp. 244-247

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2116737

Accessed: 26-10-2017 20:35 UTC

[sorry, I’m sure there are other more accessible sources on the rum trade and its parallels/uses in the slave trade, but I have google fatigue. The article is focussed on economy and is numbers and ledgers and is only really relevant to show how rum was used by the colonists in the slave trade]

https://www.thoughtco.com/triangle-trade-104592 [oh, here’s another source, and this one talks about the triangle as well]

FINALLY I want to just mention how confused I am by Louis and Richelieu and their conversation about the navy. I always read that as the French didn’t have a navy, and had a trade agreement with Spain about exploration/colonisation. I can’t find any evidence for this, however, and in fact Richelieu pretty much is the source of the modern French navy; he built the damn thing. And in terms of colonization, while it seems to be true that the French in 1630 were only just starting really, they WERE starting. Richelieu [historical type not Capaldi] went on to colonize the Antilles, and the French navy took Gorée from the Dutch in… 1677. David Gegus says that “for the little-studied seventeenth century, some data recently uncovered by Clarence Munford and others are combined with material from older works by Elizabeth Donnan, Abdoulaye Ly, and John Barbot. The compilers note, however, ‘much of the seventeenth century French traffic is missing.’ A large part of France's slave trading was then clandestine, conducted by interlopers challenging royal monopoly companies”. Which seems to fit in with Bonnaire’s position with the court. Richelieu actually set up a Company of San-Christophe with an explorer called Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc in approx. 1626 (“I found myself my own little utopia, a little piece of heaven called San Christophe”). [‘San-Christophe’ is ‘Saint Kitts’]. The company failed, d’Esnambuc died, Richelieu set up the Company of One Hundred Associates instead and they colonised Canada, the Antilles, etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Belain_d%27Esnambuc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Company_of_One_Hundred_Associates

And for those who like academical journalies and JSTOR:

Hausa Calabash Decoration

Author(s): Judith Perani

Source: African Arts, Vol. 19, No. 3 (May, 1986), pp. 45-47+82-83

Published by: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3336411

In the Shadow of the Castle: (Trans)Nationalism, African American Tourism, and GoréeIsland

Author(s): Salamishah Tillet

Source: Research in African Literatures, Vol. 40, No. 4, Writing Slavery in(to) the AfricanDiaspora (Winter, 2009), pp. 122-141

Published by: Indiana University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40468165

Accessed: 26-10-2017 18:30 UTC

The French Slave Trade: An Overview

Author(s): David Geggus

Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 58, No. 1, New Perspectives on theTransatlantic Slave Trade (Jan., 2001), pp. 119-138

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2674421

Mercantilism as a Factor in Richelieu's Policy of National Interests

Author(s): Franklin Charles Palm

Source: Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Dec., 1924), pp. 650-664

Published by: The Academy of Political Science

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2142344

The French Slave Trade: An Overview

Author(s): David Geggus

Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 58, No. 1, New Perspectives on theTransatlantic Slave Trade (Jan., 2001), pp. 119-138

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2674421

Scientific travel in the Atlantic world: the French expedition to Gorée and the Antilles,1681-1683

Author(s): NICHOLAS DEW

Source: The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 43, No. 1 (March 2010), pp. 1-17

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of The British Society for theHistory of Science

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40731001

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

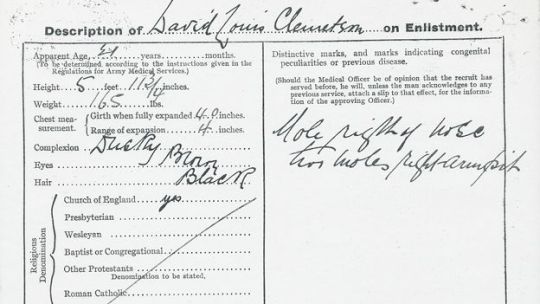

The officer who refused to lie about being black

When war was declared in 1914, a Jamaican, David Louis Clemetson, was among the first to volunteer.

A 20-year-old law student at Cambridge University when war broke out, Clemetson was eager to show that he and others from British colonies like Jamaica - where the conflict in Europe had been dismissed by some as a "white man's war" - were willing to fight and die for King and Country.

He did die. Just 52 days before the war ended, he was killed in action on the Western Front.

Clemetson's first taste of combat was in 1916 on the Macedonian Front, in Salonika.

"It is as much like hell as anything you can think of," wrote a soldier who served alongside the Jamaican.

On the frontline for eight months, under constant bombardment by big guns and badly traumatised by "shell-shock", or what's now known as post-traumatic stress disorder, Clemetson, a 2nd lieutenant, was evacuated to a military hospital in Malta.

Declared physically fit, but in need of psychiatric care, Clemetson was sent to Britain aboard the hospital ship Dover Castle, which, after a day at sea, was torpedoed by a German submarine and sank off North Africa on 26 May 1917. "Dastardly," a British newspaper roared. "The enemy must be punished!"

Rescued, the young Jamaican, who'd been diagnosed with "neurotic depression" and "stress of service" from his terrible time at the front, was taken in June 1917 to the Craiglockhart psychiatric hospital for officers in Scotland.

There, Clemetson was cared for, his medical records show, by Dr William Rivers. This pioneering physician developed a "talking cure" which helped heal soldiers who, frozen with fear from combat, were depressed, unable to sleep and eat properly, and were distraught at being branded cowards by many.

Also being treated at the hospital was the war poet Wilfred Owen, a 2nd lieutenant who had written about the futility of war and the waste of young life. Owen, like Clemetson, had been suffering from shell-shock. "These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished," reads Owen's poem Mental Cases.

Clemetson spent two months at Craiglockhart, and was almost certainly the only black officer treated there. While there, his name was mentioned briefly in the hospital magazine, The Hydra, edited by Wilfred Owen.

Two years before, in 1915, he became one of the first black British officers of WW1. But the 1914 Manual of Military Law effectively barred what it called "any negro or person of colour" from holding rank above sergeant, according to Richard Smith, author of Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War.

Nevertheless, Clemetson became a 2nd lieutenant in the Pembroke Yeomanry on 27 October 1915.

History has long recorded another black soldier, British-born Walter Tull, as the first to become an officer. But by the time Tull became a 2nd lieutenant in the Middlesex Regiment on 30 May 1917, Clemetson had been an officer for going on two years. There is a distinction - Clemetson was in the Yeomanry, part of what was then the Territorial Force, rather than the regular Army.

Another candidate for the first black officer is Jamaican-born George Bemand. But he had to lie about his black ancestry in order to become an officer. Bemand, whose story was unearthed by historian Simon Jervis, became a 2nd lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery on 23 May 1915, four months before Clemetson became an officer and two years before Walter Tull.

When the teenage Bemand and his family migrated to Britain from Jamaica in 1907, and the ship he was on made a brief stopover in New York, Bemand, the child of a white English father and a black Jamaican mother, was categorised by US immigration officials as "African-Black". Yet, asked in a military interview seven years later, in 1914, whether he was "of pure European descent", Bemand said yes. His answer was accepted.

But Clemetson took a different approach.

"Are you of pure European descent?" he was asked, in an interrogation intended to unmask officer candidates whose ethnicity was not obvious and who were perhaps light-skinned enough to pass for white. "No," answered Clemetson, whose grandfather Robert had been a slave in Jamaica, he was not "of pure European descent".

By telling the truth about his ancestry, Clemetson threatened to disrupt the military's peculiar "Don't ask, don't tell" racial practices, which were conducted with a wink and a nod.

The recruiting officers would probably have preferred that Clemetson claim he was white and leave it at that. If others had followed Clemetson's stance, the military establishment could no longer claim, if pressed, that it barred men who were "negroes or people of colour" from becoming officers and that it kept leadership roles in the military for men "of pure European descent".

The question of race seemed to shape Clemetson's brief military career. Military officials spent a lot of time trying to categorise him.

In 1914, shortly after the war began, and Clemetson had enlisted, the Jamaican was examined by a military doctor. Asked to describe what "complexion" Clemetson was, the physician didn't write black or white in his medical report. Instead he decided that Clemetson was "dusky", or between light and dark.

The military did not know what to make of their new recruit, who they saw only in terms of the shade of his skin. But there was much more to the young Jamaican than this.

Clemetson had been born into a wealthy Jamaican family which had a complicated history. Clemetson's grandfather Robert, a one-time member of parliament in Jamaica, had been a slave. Robert's owner, who was also his father, freed him and went on to leave him money, a sugar plantation, and even slaves, in his will.

This dubious inheritance allowed the Clemetsons to emerge at emancipation rich and powerful, and part of a light-skinned black elite in Jamaica which dominated the British colony. Large landowners in St Mary's parish on the north coast of Jamaica, Clemetson's family also became rich in the banana trade after setting up, in partnership with an Italian-American family in Baltimore, a company to ship and distribute Jamaican bananas and other fruit in the US.

The money from these enterprises kept the Clemetsons in comfort in Jamaica and paid for their children to attend a variety of public schools and universities in Britain. David Clemetson attended Clifton College in Bristol and later Trinity College, Cambridge. One of the wealthiest young men in Jamaica, had Clemetson not gone off to fight, he would have returned home after university and settled down to life as a rural Jamaican landowner.

Instead, he responded to Britain's massive war recruitment drive.

Acknowledging the need for black and Asian men from its colonies, Britain enlisted the help of West Indians, Africans and Indians, who they confined mostly to segregated units and ordered to do some of the most dangerous and dirty jobs, among them digging and emptying toilets, burying the dead, and transporting live shells.

It's estimated a million Indians, 100,000 Africans, and 16,000 West Indians served in the rank and file, in segregated units like the British West India regiments. In Jamaica, Clemetson's cousin Cecil did all he could to encourage young men on the island to volunteer.

"All able-bodied men should go forward and show their patriotism," roared Cecil at a recruiting rally in St Mary's parish, Jamaica, in 1915. "No country's subjects were better treated," he claimed, "than those of the British Empire."

The British military hierarchy decided it could do no harm to turn a blind eye to its own racially discriminatory laws and allow a handful of black soldiers - among them Tull, Bemand, and Clemetson - to become officers, in charge of white troops.

But it was a fairly well-kept secret. Had they been aware, many Britons would have opposed even a small, select group being allowed to bypass the rules and give orders to whites. "The presence of the semi-civilized coloured troops in Europe was, from the German point of view, we knew, one of the chief Allied atrocities. We sympathized," Robert Graves wrote in Goodbye To All That.

But others thought this foolishness, faced as Britain was with possible defeat to Germany. Maj Gen Sir AE Turner said it would have been "the height of stupidity" not to allow "coloured subjects of the Empire… to take part in the war, and take their part… in crushing the Hun".

The black officers who did make it were remarkable men.

Walter Tull was a celebrated professional footballer. Another distinction might have been glowing recommendations from powerful military officials.

Education and class were a massive factor too. George Bemand came from a well-off family and attended a prestigious public school, Dulwich College. He had also been a member of the Officer Training Corps at University College, London, and been recommended by a Brigadier-General, AJ Abdy. The general scribbled earnestly on Bemand's application: "I am willing to take him."

Clemetson, of course, was wealthy and came from a planter family in Jamaica, attended a respected public school where he was a member of the Officer Training Corps, went on to Cambridge where he was in the rowing team, and also had recommendations from important military people.

He received a recommendation from Lt Col HJH Inglis of the Sportsman's Battalion of The Royal Fusiliers, the regiment Clemetson had belonged to in 1914 before he transferred in 1915 to the Pembroke Yeomanry to become an officer.

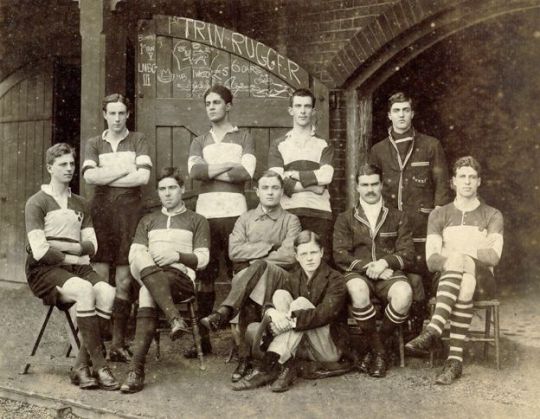

He had been attracted to the glamorous Sportsman's Battalion because it had advertised itself as a special unit for men who were at least 6ft tall and athletic, like Clemetson, who had played rugby and cricket at school before rowing at university.

Apart from the recommendation from Inglis, Clemetson also received encouragement in becoming an officer from FC Meyrick, a lieutenant-colonel in the Pembroke Yeomanry. Meyrick met and interviewed Clemetson. The Jamaican was, he reported, "in every way eligible and suitable for a Commission".

But besides the recommendations, the athletic prowess, and public school backgrounds, what it appears the military establishment most wanted black officer candidates to have, was light skin - preferably light enough to "pass" as white and fool all but the most observant.

Those who wanted to become officers but were darker-skinned, would often find themselves rejected, even if a powerful person, like the governor of Jamaica, intervened on their behalf. Take, for example, the case of Jamaican government official GO Rushdie-Gray, mentioned in Richard Smith's book.

Despite an agreement between Jamaica's governor and the War Office to make Rushdie-Gray an officer, when the Jamaican arrived in London in 1916 he was refused a commission because he was judged too dark-skinned.

"Mr Gray called today, he is presentable, but black," a War Office memo reads. "I am surprised at the Governor recommending a black man without previously informing us of his colour." There is, crucially, the memo says, "no absolute bar against coloured men for commissions… but that they did not expect Mr Gray to be the colour he is."

It appears, too, that George Bemand's younger brother Harold was blocked from becoming an officer for similar reasons. Both attended public school but while George, who was noticeably lighter than his younger brother, became a 2nd lieutenant, Harold became only a gunner - equivalent to a private. It was clear the military had decided if it was going to have black officers, they would be as light-skinned as possible.

On 26 December 1916, a year and a half after he became an officer, George Bemand, aged just 24, was killed by an enemy shell in France. On 25 March 1918, a year after he became an officer, Walter Tull, aged 29, was also killed in action on the Western Front in the "Spring Offensive". Tull's body was never recovered.

As for David Clemetson, after serving on the Macedonian Front in 1916 and being torpedoed and rescued on his way to Britain in 1917, he ended up at Craiglockhart. The hospital seems to have had a contradictory role.

Its job was to both treat the afflicted officers, but also to patch them up quickly and get them back to the front line.

Clemetson's medical records show in the two months he spent at Craiglockhart, doctors there couldn't seem to decide whether he was getting better, or was in need of more care.

On the one hand, a report reads, he was in need of "further treatment". But on the other hand, the report reads a few lines later, Clemetson had, it said, "improved much". Other reports show he was not sleeping much, and when he did he had terrible nightmares. His legs had also become so weak he could not stand properly and, the medical reports acknowledges, "his memory is not what it should be".

Clemetson did have some good news while at Craiglockhart. To his surprise, in July 1917, a letter arrived from the War Office informing Clemetson he had been promoted to full lieutenant, the only black person, it appears, to hold this rank in the British armed forces during the war.

Read more

Photographs:

David Louis Clemetson

Walter Tull died at the Battle of the Somme, March 1918

George Bemand lied about his black ancestry to ensure his commission

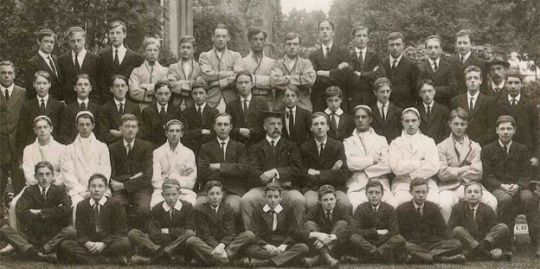

Clemetson pictured at Clifton College (front row seated, fourth from right)

Class was a factor as well as race: Clemetson (back row, 2nd from left) rowed for Trinity College, Cambridge

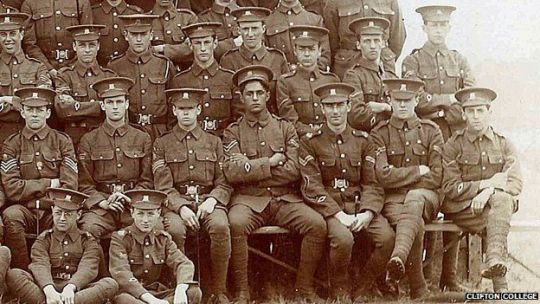

Clemetson in Clifton College's Officer Training Corps (front row seated, centre)

Clemetson's enlistment form - for the category "Complexion" a doctor has written "dusky"

#bbc#bbc news#david louis clemetson#don't ask don't tell#richard smith#jamaican volunteers in the first world war#jamaican#jamaicans#walter tull#george bemand#david clemetson#race#racism#white supremacy#war#wars#wwi#world war i#military#dusky#black soldiers#read more#long reads

1 note

·

View note

Text

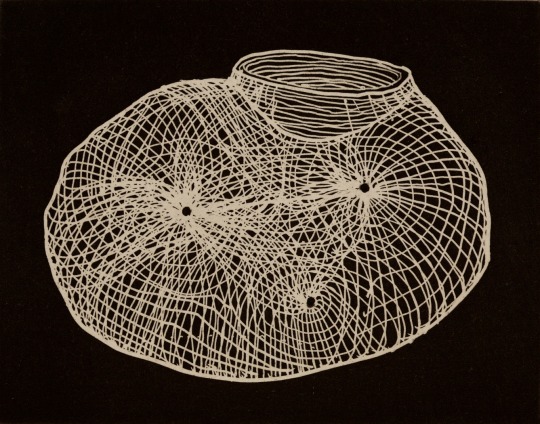

Some Thoughts About Richard Serra and Martin Puryear (Part 2: Puryear)

Like Serra, Puryear went to Yale’s famed M.F.A. program (1969–71), but he attended five years after Serra had graduated. In fact, Serra and Robert Morris were visiting artists while he was a student there. During his time at Yale, he studied with the sculptor James Rosati and took a course on African art with Robert Farris Thompson and a course on pre-Columbian at with Michael Kampen. Before attending Yale, Puryear had studied at Catholic University of America, Washington D.C. (1959–63), where he got a B.A in Arts; worked in the Peace Corps (1964–66) in Sierra Leone in West Africa; attended the Swedish Royal Academy of Art (1966–68); and took a backpacking trip with his brother in Lapland, above the Arctic Circle. By the time he attended Yale, Puryear was what the poet Charles Baudelaire would have characterized as “a man of the world.”

From the outset of his career, Puryear refused to give up what he knew and studied in order to align his work with the prevailing aesthetic. Some people believe they should do whatever it takes to fit in, while others accept that they will never fit in and do not try. There is the assimilationist who wants to be loved by everyone, and there is the person who knows that this kind of acceptance comes with a price. In Michael Brenson’s article, “Maverick Sculptor Makes Good” (New York Times Magazine, November 1, 1987), this is how Puryear described his response to Minimalism:

I never did Minimalist art. I never did, but I got real close…. I looked at it, I tasted it and I spat it out. I said, this is not for me. I’m a worker. I’m not somebody who’s happy to let my work be made for me and I’ll pass on it, yes or no, after it’s done. I could never do that.

For me, what is interesting is the nimbleness, stubbornness, determination and intelligence with which Puryear negotiated the aesthetic choices available to him in the late 1960s, a veritable minefield that stretched between the entrepreneurial and the confessional, formalist purity and identity politics.

Historically speaking, Puryear studied art in America and Sweden, lived in and traveled through Scandinavia, Europe and Africa, and worked in the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone during the convulsive 1960s. Culturally speaking, during this tumultuous decade of war, assassinations, desegregation and race riots, America witnessed the rise of Pop Art, Minimalism, Color Field Painting, Painterly Realism, Land Art and the Black Arts Movement, which was started by LeRoi Jones in Harlem in 1965, after Malcolm X was assassinated. The Black Arts Movement advanced the view that a Black poet’s primary task was to produce an emotional lyric testimony of a personal experience that can be regarded as representative of Black culture — the “I” speaking for the “we.” I doubt any of this escaped Puryear’s attention. Faced with these choices, his decisions were bold, adamant and, to my mind, inspiring.

According to Robert Storr, in his 1991 essay, “Martin Puryear: The Hand’s Proportion”:

Of major sculptors active today, Puryear is, in fact, exceptional in the extremes to which he goes to remove the personal narrative from the aura of his pieces. Nevertheless, he succeeds in charging them with an intense and palpable necessity born of his absolute authority over and assiduous involvement in their execution. The desire for anonymity is akin to that of the traditional craftsman whose private identity is subsumed in the realized identity of his creations rather than being consumed in the pyrotechnic drama of the artistic ego. As embodied in Puryear’s sculpture, however, this workmanlike reticence allied to an utter stylistic clarity is as puzzling and as evocative as a Zen koan.

Given the choices open to him between 1960 and ‘70, I don’t find Puryear’s “workmanlike reticence” puzzling, but exceptional. Recognizing that neither skill nor ideas were enough, he rejected becoming a formalist using outside sources to make shiny objects, refused to rely purely on his skill, recognized that craft was a storehouse of cultural memory, and chose not to become an “I” speaking for a “we.” Choosing the latter would have likely required that he evoke his ancestry while making art that alleviated liberal guilt. Influenced by Minimalism’s emphasis on primary structures, which were supposedly objective and non-referential, Puryear inflected his pared-down forms with the possibility of a shared or communal state as well as with a marginalized history that is both haunted and haunting.

In Puryear’s work, it is not an “I” using the form to speak, but a diverse and complex “we” speaking through the form. I think that in his devotion to craft (or his “workmanlike reticence”), which he always puts at the service of his forms, Puryear is attempting to draw upon this storehouse of cultural memory, in order to channel all the anonymous workers and history that preceded him. It is their eloquence, tenderness and pain that he wants to tap into because he understands that he cannot speak for them. The work functions as testimony and homage whose meanings (or narratives) don’t necessarily fit neatly together.

I cannot stress this enough. Puryear goes beyond simply remembering those who are invisible or marginalized, a “we” that is pushed to the sidelines; he also enlarges the definition of “we” through his work. As underscored by such titles as “Some Lines for Jim Beckwourth” (1978), “Ladder for Booker T. Washington” (1996) and “Phrygian Plot” (2012), this “we” isn’t defined by a single race, culture or history. (Jim Beckwourth, 1798-1866, who was bi-racial, was freed by his father and master and became a renowned explorer and fur trader; later in his life, he was the author of an as-told-to autobiography (written down by Thomas D. Bonner) about his life among different cultures and races: The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth: Mountaineer, Scout and Pioneer, and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians [New York: Harper and Brothers; London: Sampson, Low, Son & Co., 1856].) In this regard, Puryear has never been an essentialist in his materials, approach to art, or subject matter. By not following in anyone’s footsteps, aligning himself with a pre-established aesthetic, or branding his work, Puryear has gained for himself what all artists and poets are said to desire most: artistic freedom.

With “Cedar Lodge” (1977), which Puryear built shortly after his studio in the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn burned down on February 1, 1977, he completed the first of what might be defined as a sanctified space. At the same time, “Cedar Lodge” feels temporary. In fact, the artist dismantled and destroyed the piece after it was exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., perhaps because there was no place for him to store it.

In “Self” (1978), which Neal Benezra describes in his 1993 essay, “’The Thing Shines, Not the Maker’: The Sculpture of Martin Puryear” as “a dark monolithic form,” Puryear is able to convey the illusion of a solid, heavy form “planted firmly in the earth,” and therefore partially hidden. And yet, as one learns from looking at the sculpture, the self is not inherited, a byproduct of nature, but something that is made, created out of what is at hand. According to the artist:

It looks as though it might have been created by erosion, like a rock worn by sand and weather until the angles are all gone. Self is all curves except where it meets the floor at an abrupt angle. It’s meant to be a visual notion of the self, rather than any particular self–the self as a secret entity, as a secret hidden place.

In these early sculptures, Puryear began further defining a path that distinguished him from every movement as well as from his elders and peers; he was on his own path. Central to his decision is a belief in interiority; sacred spaces; a self-created private self; survival and temporariness. At the same time, knowledge of craft, which has cultural roots, and a study of history play a significant role in Puryear’s work. What is deemphasized in these works is the “I” or artistic ego.

Puryear’s philosophical position occupies the opposite end of the spectrum from the influential one taken by Andy Warhol: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

Or, for that matter, Frank Stella: “What you see is what you see.”

In works such as “Bower” (1980) and “Where the Heart Is (Sleeping Mews)” (1981), which was inspired by a Mongolian yurt, the artist alludes to the movable house, a temporary sanctuary that can be quickly transported from one place to another. At the same time, as Elizabeth Reede notes in a footnote to her essay, “Jogs and Switchbacks” (2007):

"Puns are not uncommon in Puryear’s titles. A mews is a hawk house, and the title Sleeping Mews is a pun on Constantin Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse (1910)."

In using puns, Puryear recognizes that neither language nor meaning is fixed or stable, that everything is contingent. Seemingly mobile, Puryear’s sculptures both critique and share something with Serra’s take on the relationship between viewer and object, which I cited earlier:

"The historical purpose of placing sculpture on a pedestal was to establish a separation between the sculpture and the viewer. I am interested in creating a behavioral space in which the viewer interacts with the sculpture in its context."

Rejecting the pedestal, Puryear places his works directly on the floor. Often composed of both an exterior form, such as a sensual, layered skin or a skeletal, enclosing structure, and an inaccessible but visible interior space, the sculptures invite the viewer’s interaction; they evoke a behavioral space in which a possible intimacy can occur. Whereas Serra’s space tends to privilege an authoritarian shepherding of the viewer through a carefully designed, architectonic structure, Puryear’s work seems to invite the viewer’s speculation as it creates a space of reflection. Made at the beginning of a decade dominated by the “death of the author,” the denigration of craft and skill, the promotion of entrepreneurship, and the elevation of appropriation, Puryear’s “Bower” and “Where the Heart Is (Sleeping Mews)” represented a direct challenge to mainstream art and thinking.

Here, the difference between Serra’s site-specific installations and Puryear’s sculptures cannot be clearer or more telling. In sculptures such as “C.F.A.O. “(2006-2007), “Ad Astra” (2007), “Hominid” (2007-2011), “The Rest” (2009-2010) and “The Load” (2012), Puryear uses wheels he has had in his possession for many years as well as rounded posts and a wheelbarrow to convey the sculpture’s mobility; it is something that can be moved from one place to another, from an open public space to a hidden one, if necessary.

“Ad Astra” is a sculpture incorporating two wheels that the artist found fourteen years earlier on a farm in France. A crystal-like form defines the body of the wagon, which has been described as chariot-like. A tripod has been built into the axle; and from the tripod a stripped-down tree trunk rises more than sixty feet into the air.

In his 2007 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Puryear placed “Ad Astra” and “Ladder for Booker T. Washington” in the museum’s five-story-high Marron Atrium. It seems to me that Puryear placed these works there for a number of reasons, which have less to do with their size and more to do with the dialogue they uphold between history and aspiration, adaptability and inflexibility, particularly with regard to human rights and equality.

Booker T. Washington, who was bi-racial, is a complex figure in America, at once revered and reviled. Considered a racial accommodationist, he rejected the pursuit of racial equality in favor of vocational training. As the first principal of Tuskegee Institute, a school founded after the Civil War for African-Americans, he helped establish the reputation of the school as well as secured its financial stability. Meanwhile, the thirty-six-foot crooked ladder, which alludes to ambition, objectives, to what Washington called “racial uplift,” and to Jacob’s Ladder (or the staircase to heaven that Jacob dreams about in the Bible), is nearly a foot wide at the bottom and a little more than an inch wide at the top. At the Museum of Modern Art, “Ladder for Booker T. Washington” was suspended in the air by wires so that it hung three feet off the ground, becoming a doubly impossible ladder to climb.

By playing with the relationship between perspective and the actual physical length of the piece as it recedes into the distance, Puryear assembled a visual conundrum in which the viewer could not tell if the artist manipulated its rate of diminishment or if it was in fact naturally thinning into space. Instead of stripping all possible illusionism from the work, which, according to Krauss, is one of Serra’s highest achievements, Puryear employs illusionism to carefully orchestrate the misalignment of the visual and the physical, resulting in a perceptual paradox. In doing so, he synthesizes formal issues with his knowledge of history to create a form from which a variety of different and contradictory meanings can be teased out. In “Ladder for Booker T. Washington,” Puryear has used a simple, recognizable form to develop a prolonged mediation on American history and racial relationships. It is a piece that raises a multitude of questions rather than offers solutions.

By playing with the relationship between perspective and the actual physical length of the piece as it recedes into the distance, Puryear assembled a visual conundrum in which the viewer could not tell if the artist manipulated its rate of diminishment or if it was in fact naturally thinning into space. Instead of stripping all possible illusionism from the work, which, according to Krauss, is one of Serra’s highest achievements, Puryear employs illusionism to carefully orchestrate the misalignment of the visual and the physical, resulting in a perceptual paradox. In doing so, he synthesizes formal issues with his knowledge of history to create a form from which a variety of different and contradictory meanings can be teased out. In “Ladder for Booker T. Washington,” Puryear has used a simple, recognizable form to develop a prolonged mediation on American history and racial relationships. It is a piece that raises a multitude of questions rather than offers solutions.

In an interview in the Brooklyn Rail with David Levi Strauss, Puryear, speaking about “Ad Astra,” stated:

There are two Latin phrases the title derives from: Ad astra per ardua, meaning “to the stars through difficulty,” and Ad astra per aspera, which translates as “to the stars through rough things or dangers.”

The ungainly wagon, which is at rest, underscores that one must be prepared to undertake any journey toward fulfillment despite the obstacles. At the same time, there is something impractical about the wagon with this tree trunk rising into the air and seemingly vanishing into infinity. Meanwhile, the body of the wagon evokes a crystal, a form that is both organic and geometric. We think of it as transparent and, as the Greek root (krustallos) suggests, cold or made of rock. By making it out of wood, Puryear has undermined our associations with the crystal-like form, complicating any single or simple reading of the sculpture.

Along with such works as “C.F.A.O.,” “Hominid,“ “The Rest,” and “The Load,” all of which have wheels or rounded, post-like forms suggesting mobility, “Ad Astra” challenges the long held idea of a sculpture as a stationary form, pedestal or no pedestal. A stationary form (whether sculpture or monument) suggests a belief in stability and eternalness, ownership and entitlement. As Percy Bysshe Shelley ends his sonnet, “Ozymandias”:

And on the pedestal these words appear: My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Ozymandias, who possesses the giant artistic ego, commands others to do his work.

Like “Ad Astra,” Puryear’s bronze wagon, “The Rest,” with its nearly black patina, rests on its backside, its pull-bar jutting into the air. Has the journey come to a halt, been interrupted, or will this form of transportation, which evokes the wagons used to transport runaway slaves along the underground railroad, be needed again to carry something through enemy territory?

“The Load” is a two-wheeled wagon that holds a cage-like wooden cube made of an open-lattice grid. Inside the painstakingly constructed grid is a giant eyeball made of white glass with a black circle (or pupil) in one section. Is it an open box for prisoners? Viewers can peer into the black circle and discover their reflection in a mirror, which allows them to investigate the ribbed dome from inside, temporarily becoming a “prisoner.” In this case, it is as if the giant eyeball (or hapless witness) has entrapped us.

In his reversal of the viewer’s position (from witness to victim), his challenges to permanence, stability and ownership, his recurring evocations of mobility, migration and survival, his meditations upon history, particularly colonialism, his reminder that craft is a form of memory, Puryear effectively challenges the status quo that believes in sculpture as a stationary object (a sign of stability); the death of the author and craft; the primacy of entrepreneurship; and a euro-centric view of art history culminating in a celebration of the purely formal. More than continuing a tradition of sculpture, Puryear effectively re-imagines it. In doing so he asks us to examine what we take for granted and why. This is the lively and heated conversation that Puryear and Serra are having through their work. Perhaps it is time to begin weighing in.

Source: Hyperallergic / John Yau. Link: Some Thoughts About Martin Puryear Illustration: Martin Puryear [USA] (b 1941) ~ 'Untitled I', 2002. Aquatint on Rives Lightweight Buff paper (12 x 15 cm). Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#art#contemporary art#martin puryear#sculpture#article#brainslide bedrock great art talk#hyperallergic

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

World of Qarqa: to be drawn

This is a list for myself (and potentially for artists i may commission) of stuff i want to be drawn in the future to develop the setting of Cypora’s Guide to Becoming an Evil Queen, the fantasy world of Qarqa.

Qarqa is a high fantasy setting based on two key sources of folklore: Jewish, and North American. Because of that, it differs strongly from your usual elves & dwarves Tolkienesque fantasy setting in many ways, but also deliberately uses aspects of those as a base—there are people living in Cypora’s world who think that the universe works according to rules we might recognize as those of a tabletop RPG like Dungeons and Dragons.

New commissions will depend on how much i receive in weekly donations (more info at this link).

Characters

Cypora Schenk: the protagonist. A tavern-keeper’s daughter. A transgender girl; pale-skinned with a too-slim body hardened by work & later training set beneath a large and unruly puff of curly auburn hair. Codes as Ashkenazic/Persian mix.

Alícha de Matos: the deuteragonist. An orchard owner’s daughter. A transgender girl, short and athletic with a martial artist’s build. Usually wears high-waisted denim trousers and a dark green jacket from a naval uniform, with mulberry-hued trim added and the coat of arms of Martıkoy sewn onto the front (see below). Codes as Sephardic.

Acantha: the corn dolly. A feathertop; a being made of corn husks and straw in the likeness of a modestly-dressed young woman almost constantly smoking a long-stemmed pipe. Wields an old scythe and a beaten but well-sharpened hay knife.

Adara: a sister-in-law. Strale’s wife.

Aletheia: a maid. A tall golem made of wet clay, which serves to keep the innermost areas of the dungeon in working order.

Almaz: an adventuring warrior. Dark-skinned and heavily armored woman with finely braided hair kept in a tight, high ponytail. Later: harder, colder, with a false eye made of gold and scars around it.

Astruc: a swashbuckler. Androgyne grandchild of Zalema, a chubby and bouncy type who likes to make their presence known with flashy displays and bold actions. Wears lots of colors, beads in their hair. Codes as mixed ancestry.

Bang: the tinker. A yeahoh; a kind of bigfoot notable for a broader frame and darker fur. Disguises himself as merely a tall, hirsute, & full-bearded human by wearing leather traveling garb that covers most of his body. A transgender boy, younger than he seems at first.

Earsel I: a dead emperor.

Enosch Schenk: an elder brother.

Fagim Fossoyeur: an undertaker. A single father trying to do the best by his daughters, glad they have good friends.

Guta Schenk: an tavern-keeper. Cypora’s mother, short and exceptionally strong. Codes as Ashkenazic.

Ishvi Med: Keturah’s baby brother.

Ivorde Consley: a dead businessman.

Joia-Douce Bleustein: a loup-garou.

Keturah Med: the beekeeper. Daughter of a family of mead-makers, chubby nerd with an interest in all arthropods. Very dark-skinned, with an especially voluminous afro. Wears reinforced beekeeping garb as armor. Codes as Beta Israel.

Libet Schenck: a middle sister.

Licoricia Fossoyeur: the angelspawn/naphil. Daughter of an undertaker and an angel; brown skin and long, loosely braided hair kept back in a low ponytail. Her eyes are an unnatural blue not found among mortals, and more of them open all over her body (and in the air beyond it) when she is agitated. Armed with a sharpened shovel. Codes as an African-American Jew.

Madrona: a witch. Acantha’s creator, a wise old bubbe in a simple gray dress, usually hunched over so much that her full height of nearly two meters is not apparent. Codes as Litvak.

Melisende: a healer. A lutin, voluptuous and mature at about 2′3″, able to take the form of a white cat.

Musa (formerly Marx in early drafts) Schenk: a tavern-keeper’s husband. Codes as a Persian Jew.

Orangella Fossoyeur: the demonspawn/mazik. Daughter of an undertaker and a shedah (demoness); her feet look like those of a giant chicken, or maybe a dinosaur. Noticeably paler than her sister Licoricia or father Fagim. Codes as a biracial African-American & Ashkenazic Jew.

Pesche Schenk: an eldest sister. Tall & sturdily built, her curves cover working muscle. Widely admired for her healthful looks and dedication.

Poncella de Matos: an apple orchard owner.

Raduard: an adventuring mystic. All narrow angles, thin-lipped and pale eyed.

Ravid: a sibling-in-law. Libet’s spouse.

The Rear Admiral: a monster. A giant cecalia clad in a naval uniform sewn together from ships’ sails, dyed green and set with ornaments of gold thread. It had a cluster of barnacles in place of a beard, and kept its hair in the most filthy matted parody of dreadlocks you could imagine outside of a folk music festival. Its tentacles were disproportionately thick compared to its upper body.

Scoloaster Spitznogle: an undead. A vampir, wrapped in a shroud and with too-long nails; her sharp teeth are exposed by her lack of lips.

Shiaroc pla Aurm: a lizard woman. Distinguished by abundant scars and light stripes, as well as an unusually thick tail. Wears a high-collared heavy leather jacket and skirt as armor, reinforced with slats of exotic hardwoods.

Shokh: the Schenk family’s reliable old ox, a great and powerful critter. Reference “Belted Galloway” breed.

Simham: a spice trader. A handsome but anxious young man who has traveled a long way and thinks very highly of Enosch.

Strale Schenk: a second brother.

The Old Goat: an overlord. A gigantic goatman who served as the first overlord of Dungeon #1540, two and a half meters tall but very slender. He soaked his fur in pine tar to stick bits of flint in it as armor, and wielded an axe that magically dripped blood, together with an enchanted lantern.

The Stranger: a visitor. A “phantom monster” that observes the inhabitants of Dungeon #1540. Reference the Flatwoods Monster.

Toiba: a boss. The leader of the kapelyushniklekh, she wears a fine bowler hat decorated with a plume of feathers that doubles her height.

Tomer Med: Keturah’s father. A man with a very large belly, full cheeks, and exceedingly long dreadlocks.

Toussaint: a prophet. A mothman who believes he is the envoy of the goddess Misfortuna, whom nobody has ever heard of.

Vivard: a novice. An inexperienced adventurer who took to the lifestyle as a means to rise above his station as an orphan.

Dom Xandre Nunos: A restaurant owner. A famously skilled arm-wrestler fond of challenging rowdy patrons.

Zalema: An old salt. A man built like the timbers of an old dock, sturdy and weathered, and gay as the day is long. Codes as Romaniote.

Tzufit Med: Keturah’s mother. A tall woman with very dark skin, and high cheekbones.

Groups of People