#Hassan Dehqani Tafti

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

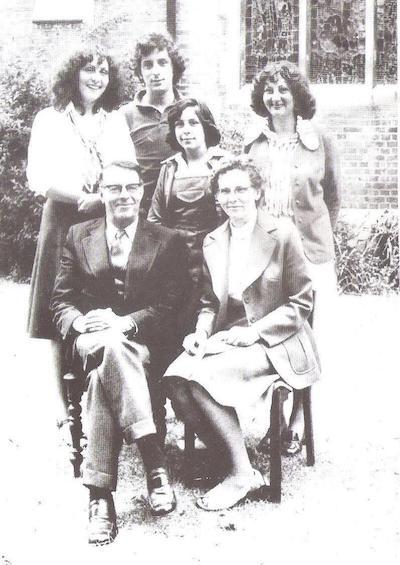

Bishop Hassan Dehqani-Tafti (bottom left), with his wife (Margaret, bottom right), and children (daughters Shirin, Sussanne, and Guli; son Bahram). Source. The Right Reverend was the first ethnic Persian to hold to office of Bishop of Iran in the Anglican Church. Dehqani-Tafti was technically a convert to the faith, but Christianity was an interwoven element in his life from before his birth. A gradual process, Dehqani-Tafti’s conversion highlights how blurred the lines Christianity and Islam can be. The outline of this relationship, given below the cut, is derived from the doctoral thesis of Sister Agnes Angela Wilkins, “From Islam to Christianity: A Study in the Life and Thought of Hassan Dehqani-Tafti and Jean-Mohammed Abd-El-Jalil in the Ongoing Search for a Deeper Understanding Between Christianity and Islam,” itself heavily reliant on the Right Reverend’s autobiography.

Childhood and Education

Hassan was the son of Mohammad, an illiterate but pious Muslim, and Sekinah. Sekinah, the daughter of a ‘Mulla Zahra,’ who received that honorary title for being able to read and recite the Qur’an, was a convert to Christianity. She had worked as a nurse with her mother in a missionary hospital, and it was there that she decided to be baptized. She also learned to read and write. After being married to Mohammad, she had three children, the middle one being Hassan. For the first five years of his life, Hassan, despite being raised a Shi‘a Muslim, remembers visits from the missionaries and singing songs with Biblical themes. This changed after his mother died, when he was about five years old. Before her death, Sekinah had requested that a friend of hers help raise at least one of her children to be Christian; this friend, a Ms. Kingdon, spent about a year and a half trying to convince his father to allow it. Ultimately, the boy was allowed, spending about a year in an otherwise all-girls school. There, he learned The Lord’s Prayer and memorized a few psalms, in addition to learning the Persian alphabet. Once he beeccame too old to stay at an all-girl’s school, the boy was sent to a missionary school in the former Safavid capital of Isfahan. It was there that he studied calligraphy, poetry, and Scriptures under the headmaster Jalil Aqa. Jalil Aqa was of Cossack descent, but had fully integrated into the Persian culture of his upbringing. As a young man, he was a Sunni Muslim, but with a strong mystical bend. He converted to Christianity through conversations about the relationship between Christ and the body of believers with missionaries at a hospital. Jalil Aqa represented a kind of Christianity that “digested the best of Persian culture, and then had baptized the whole into [itself].” Nonetheless, the young Hassan would oscillate between the Christianity of his schooling and the Islam of his family life. By the time he was 15, his father wavered over whether he should continue to allow his son to go to school, but ultimately allowed him to; by 17, Hassan had written a list of 77 resolutions he wished to follow; by 18, he was a baptized Christian. Many friends no longer spoke to him, he could no longer eat from the same bowl as his family, and contact with him made his loved ones ritually impure. His father described watching his son convert to Christianity as akin to having his hand cut off.

Crisis

The first few years after baptism were relatively easy. He attended the University of Tehran as a closeted Christian. Most students were more interested in secular philosophy and Western culture to really care anyway, but a couple people that he did tell were supportive or disgusted. When he had to join military service, he had to out himself, and was dismissed by his superior for being untrustworthy for having apostasized from Islam. Problems arose, however, when he considered ordination. His military service had given him a good salary, and his family -who also did not like the idea of the social suicide he would undergo as a pastor- attempted to convince him to remain there. Instead, the local missionaries encouraged him to go to Cambridge University, where he felt a loneliness he had never felt before. He began to resent God for his mother’s death, blame the missionaries for the widening gap between himself and his family, and even consider suicide. This crisis was resolved through forming a relationship with Bishop Stephen Neill, who seems to have taken on a fatherly role to him. Although they only met in person six times, the two would continue to correspond through letters. It is around this time that Hassan developed a strong attachment to the Book of Job, and felt a calling to a deeper sort of repentance, a total reorientation of his life. Though offered a job at Cambridge, he wanted to continue his ministry in his home country.

Returning to Iran

Though he was frequently visited by the Detective Bureau of Police, an frequently dealt with minor harassment, the early years of Hassan’s return were happy ones. In 1949 he was ordained a deacon in the Anglican Church (an organization whose theological leanings Kingdon did not approve of, though she was happy for him). In 1950, he was made a priest, and in 1952 he married the daughter of the current Bishop of Iran (Margaret, pictured above). In 1960, he was consecrated the Bishop of Iran. Hassan’s father died in 1970, and his attempt to attend the funeral only highlighted how large the rift between his family and himself had become. His brother did not want him there, and a group of mullahs refused to let him enter, forcing him to pray for his father outside the mosque. The growth that the Anglican Church in Iran would experience, including the establishment of more hospitals and programs to help make the blind community more self-sufficient, was reversed in the early weeks of the Revolution. Although the land that the hospitals were built on was waaf, a semi-sacred gift under Islamic law, they were seized by Revolutionaries after a senior priest was murdered. His house was ransacked, and threatening messages sent to his house. The anxiety and stress left him bedridden for three weeks. During this time, he decided that taqiyya, pretending to assimilate into the larger religious majority, could not be a strategy for the threatened Christian community: “Christ was almost ruthless about being and showing who you are.” Hassan found inspiration from the life of Saint Thomas Moore, an English Catholic who was killed for refusing to renounce his faith during the Anglican Reformation, and attributed his recovery to a “new infilling of the love of God.” If he were to be killed, then he would be killed; “The important thing is to continue God's work with utmost loyalty to the end.” This was a good attitude to have, because he was soon arrested and interrogated for access to a diocesan bank account. He was forced to stay in a yard where public executions by firing squad happened, he was brought to a revolutionary court, and was the victim of an assassination attempt - an attempt that ended with his wife being shot in the hand after she threw herself in front of him. The two were ultimately sent to Cyprus, with the hope of reuniting with their family. Unforunately, the situation in Iran became too much, and after his son was assassinated (an act that Hassan forgave the killers for), the family was permanently moved to England.

A Persian Christian

The nineteen year exile that lasted from 1979 to his death was very hard on Hassan. The Bishop of Iran was an Iranian who loved his country and his culture. In the early years of his bishopric, he had worked with thinkers like Kenneth Cragg in an attempt to reconcile his Islamic Persian heritage with his Christian faith. In his writings, Dehqani-Tafti wrote for a mixed Christian and Muslim audience. His largest influence in the formation of his faith was a man who did not see Christianity as something at odds with Persian culture. The name of Dehqani-Tafti’s memoir, The Unfolding Design of My World, is a reference to the Naqsh-i-Jahan (Design of the World) Square, a prominent landmark in his beloved Isfahan. His gravestone has a Persian translation of Ephesians 2:19 (“So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the holy ones and members of the household of God”) engraved onto it. His pectoral cross has been returned to Iran, where it is displayed in the Isfahan church he spent so much time in.

8 notes

·

View notes