#Harriet Jacobs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The beautiful spring came, and when nature resumes her loveliness, the human soul is apt to revive also.

美しい春が訪れて自然が愛らしさを取り戻すとき、人間の魂もまた蘇る傾向にある。

Harriet Jacobs ハリエット・アン・ジェイコブズ

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harriet Jacobs: Incidents in the life of a slave girl, Ch.XLI

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What does he know of the half-starved wreaths toiling from dawn till dark on the plantations? of mothers shrieking for their children, torn from their arms by slave traders? of young girls dragged down into moral filth? of pools of blood around the whipping post? of hounds trained to tear human flesh? of men screwed into cotton gins to die?"

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

#incidents in the life of a slave girl#harriet jacobs#slavery#american slavery#abolition of slavery#abolitionist#liberation#liberty#freedom#racism#racism in america#human rights violations#human rights abuses#poc#black academia#black feminism#black liberation#american authors#american literature#literature#literature quotes#race theory#race and gender#race and ethnicity

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Friend! It is a common word, often lightly used. Like other good and beautiful things, it may be tarnished by careless handling; but when I speak of [You] as my friend, the word is sacred."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truly, the colored race are the most cheerful and forgiving people on the face of the earth. That their masters sleep in safety is owing to their super-abundance of heart[.]

Harriet Jacobs (Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Chapter XVI)

The oligarchic character of the modern English commonwealth does not rest, like many oligarchies, on the cruelty of the rich to the poor. It does not even rest on the kindness of the rich to the poor. It rests on the perennial and unfailing kindness of the poor to the rich.

G.K. Chesterton (Heretics, pages 106-107)

Let the praise of God be on their lips and a two-edged sword in their hand, to deal out vengeance to the nations and punishment on all the peoples; to bind their kings in chains and their nobles in fetters of iron; to carry out the sentence preordained; this honor is for all His faithful.

Psalm 149:6-9

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

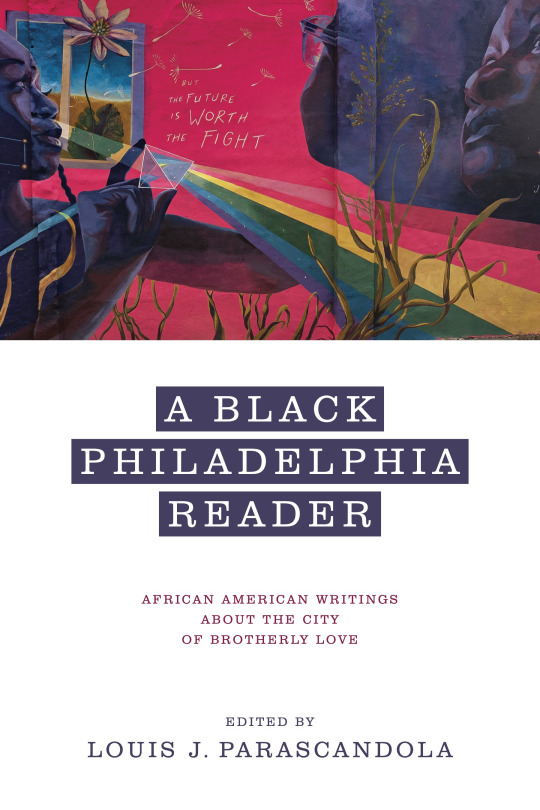

A Black Philadelphia Reader: An exerpt

The common date given for the settlement of Philadelphia is 1682, when William Penn established a Quaker colony, providing it with a name that means “one who loves his brother.” Penn intended an idyllic “greene country towne,” one that was well ordered, with large open spaces within its twelve hundred acres. It “was the first major American town to be planned.” Penn envisioned his “towne” as a place of freedom, particularly in terms of religion. As with a certain amount of history, much of this is myth. The land, of course, had been settled by the Lenape Indians long before the Europeans arrived. Additionally, Penn’s “greene country towne” soon became a highly congested city, plagued by disease, crime, and fires. Its vaunted freedom was largely limited to White Protestants, and its “brotherly love” certainly did not extend to most immigrants, to non-Christians, or, in particular, to its Black residents.

Blacks have been at the center of Philadelphia’s history since before it was even known by that name. More than two thousand Blacks lived in the area once called New Sweden between 1638 and 1655. The fledgling colony encompassed parts of western Delaware and parts of Pennsylvania that now include Philadelphia. One of the most famous of these settlers was Antoni Swart (Black Anthony), a West Indian who arrived in the colony in 1639 aboard a Swedish vessel. Though initially enslaved, records indicate he eventually became free and was employed by Governor Johan Printz.

The history of Black Philadelphians has been one fraught with both great promise and shattered dreams from its beginnings until today. Philadelphia was, as historian Gary Nash observes, “created in an atmosphere of growing Negrophobia”; still, despite ongoing racial prejudice, “it continues to this day to be one of the vital urban locations of black Americans.” It is this paradoxical condition that is the most characteristic dynamic of the city’s relationship with its Black citizens. One facet of this relationship has been constant: whether African Americans have thrived here or suffered egregious oppression, they have never remained silent, never letting anyone else define their situation for them. They have always voiced their own opinions about their condition in their city through fiction, poetry, plays, essays, diaries, letters, or memoirs. The city has been blessed with a number of significant authors, ranging, among others, from Richard Allen to W. E. B. Du Bois to Jessie Fauset to Sonia Sanchez to John Edgar Wideman to Lorene Cary. In addition, there have been numerous lesser known but also forceful figures as well, including the enslaved people Alice and Cato, who were only known by those names. Whether they were native sons and daughters or spent significant time in the city or were there only long enough to experience the city in an impactful moment, Philadelphia has touched them all deeply. This anthology is a documentation of and a tribute to their collective voice. The focus here is not just on writers with a Philadelphia connection but on the authors’ views on the city itself. The hope is to provide a wide variety of Black perspectives on the city.

There is something special about what leading African American intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois once labeled “the Philadelphia Negro.” One reason for this uniqueness is the city’s relationship to its Black inhabitants, in part caused by their intertwined, virtually symbiotic, history. No other major Northern city in the country has had such a long connection with African Americans, one forged in the seventeenth century, and Blacks have never stopped coming. They first settled largely in what are now called the Old City and Center City, where some Blacks still live. They have since scattered throughout the city, sometimes by choice but often by necessity and force, today mostly residing in Northern and Western Philadelphia. Migration patterns have changed over the years, as in other cities, but the Black population in the city has rarely declined and has often increased in number. Philadelphia was, as of 2020, the sixth-largest metropolis in the nation, and Blacks make up more than 40 percent of the population there, more than the percentage of any of the other top ten cities in the country.

Philadelphia has a vibrant and culturally rich history, offering enormous promise to its inhabitants since its beginnings. It was founded with the premise of religious freedom and steeped in the radical independence movement that created this country. The city was settled by Quakers, perhaps the religious group that, in popular opinion if not always in fact, has most vociferously been associated with opposition to slavery. The “peculiar institution” was, in fact, almost nonexistent there by the early years of the nineteenth century. Philadelphia was the center of the Underground Railroad, with such legendary conductors as William Still. As the closest major city situated above the Mason-Dixon line, symbolically separating the North from the South, many fugitives from enslavement passed through Philadelphia. Some moved on, but a large number stayed, as the city seemed like the promised land for many African Americans. This is the powerful narrative of the city’s history that still holds true for numerous people today when they think of Philadelphia.

There is also something unique about the Black experience in this city. Blacks have had a nominal freedom throughout most of their existence in Philadelphia, yet when we look under the surface, Philadelphia’s treatment of African Americans has hardly been benign. The city has held out promises, but unfortunately many of these promises were not kept. Philadelphia may be situated in the North, but as Sonia Sanchez so eloquently writes in her poem “elegy (For MOVE and Philadelphia),” in many ways “philadelphia / [is] a disguised southern city.” There were Quakers, many of whom were abolitionists and worked for the Underground Railroad, but there were many others of the faith who were slaveholders, including the colony’s founder, William Penn. And even if the city was replete with abolitionists, it did not ensure that they viewed African Americans as equals. Blacks were, in fact, disfranchised from the vote in 1838, never to regain it until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. Although the city was the center of the antislavery movement, not all of its White residents opposed slavery, and even if they did, the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 hampered efforts to keep Blacks out of bondage. Before and after the Civil War, as demonstrated throughout this text, the city experienced a series of violent racial conflicts and has continue to practice an ugly pattern of segregation in housing, transportation, education, and employment, severely limiting the prospects of improvement for its Black citizens. There is a long history of racial injustice practiced by Philadelphia’s police as well as Black residents being ignored, at best, by the city government.

A Black Philadelphia Reader: African American Writings About the City of Brotherly Love is available for pre-order from Penn State University Press. Learn more and order the book here: https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-09731-2.html. Take 30% off with discount code NR24.

#Philadelphia#Philly#Pennsylvania#African American#African American History#PA History#Pennsylvania History#City of Brotherly Love#Black Writers#Black Authors#Black Writer#Black Author#W. E. B. Du Bois#Harriet Jacobs#Sonia Sanchez#John Edgar Wideman#Public Health#Housing#Policing#Criminal Justice#Public Transportation#Urban Studies

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the crawlspace above the main floor of her grandmother's house, where she confined herself for more than seven years to escape mastery's sexual predation (in this first instance a Southern man with Southern principles) Harriet Jacobs (and/or Linda Brents, her shadowed, shadowing double and counteraffective effect) is on the way to cinema, precisely at the place where fantasy and document, music and moaning, movement and picturing converge. Hers is an amazing medley of shifts, a choreography in confinement, internal to a frame it instantiates and shatters.

from Black and Blur by Fred Moten

#Fred Moten#Black and Blur#Harriet Jacobs#Linda Brents#the afterlife of slavery#beholding Black intimate geographies#we seize horror as we bow#the torments of fleshiness

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The brightest skies are always foreshadowed by dark clouds.”

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

every american high school should have Harriet Jacobs’ writings on their curriculum.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It was always the custom to have a muster every year. On that occasion every white man shouldered his musket. The citizens and the so-called country gentlemen wore military uniforms. The poor whites took their places in the ranks in every-day dress, some without shoes, some without hats. This grand occasion had already passed; and when the slaves were told there was to be another muster, they were surprised and rejoiced. Poor creatures! They thought it was going to be a holiday… It was a grand opportunity for the low whites, who had no negroes of their own to scourge. They exulted in such a chance to exercise a little brief authority, and show their subserviency to the slaveholders; not reflecting that the power which trampled on the colored people also kept themselves in poverty, ignorance, and moral degradation."

—Harriet Ann Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

[emphasis mine]

0 notes

Text

Page 115 of Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861. Edited by L. Maria Child for its author, Jacobs, who uses the pseudonym Linda Brent.

This section on Norcom's connection to the Episcopal Church will be brief, but I'd be remiss to omit one of my favorite quotes from Incidents. My Spring 2024 paper started with the above quote from Jacobs, lamenting that Dr. Flint, or Norcom, became even worse after he became a communicant of the Episcopal church. That quote from Jacobs...

...lamenting that Dr. Flint, or Norcom, became even worse after he became a communicant of the Episcopal church. That quote resonated with me because it captured the essence of my argument: Norcom, despite presenting himself as a purified, Godly figure in public and through his personal correspondence, was, in truth, a profoundly evil man whose actions were the antithesis of the values he claimed to uphold.

Norcom was a communicant of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Edenton, North Carolina, where Jacobs and her brother John were baptized. As Jean Fagan Yellin notes in her edition of Incidents: “...the date Norcom became a communicant of St. Paul’s is not recorded,” but he was involved with the church as early as 1805. He was listed as one of six vestrymen on February 14, 1828. He was again "unanimously chosen [him] to fill the vacancy about to be created by the removal of our present pastor," by the Vestry of St. Paul’s Church due to his "private & professional character." Eventually, in 1838, he became one of two Wardens. As part of the Vestry, Norcom was involved in overseeing support for the poor, including setting maintenance rates at annual parish meetings.

Interestingly, Norcom’s affiliation with the church predates 1813, the year Jacobs was born. He may have already been a communicant during that time, though not necessarily a devout attendee. However, a noticeable shift in his religious tone emerges in his personal correspondence during the 1830s, particularly after 1833, following a severe illness that appeared to deeply unsettle him.

In a letter to his wife Maria, dated January 12, 1818, Norcom reflects on religion with skepticism, saying that, while not "improper or unnecessary," he finds it difficult to reconcile:

"Suppose for a moment that we are religiously inclined & wished to join some religious society. To what society should I attach myself? We know there are many Christian societies, each thinking itself right. How reason teaches us that they may all be wrong, but for its part believes that they can all be right. The truth is, if there be any essential difference between them, there can be but one right; and how extremely improbable is it, among the number which prevail, that I should make choice of the only true one. The chance would be at least a thousand to one.

This statement supports Jacobs’ assertion that Norcom’s association with the church was not born of spiritual conviction but rather professional and public necessity. Before 1833, his letters rarely reference God or religion. However, his perspective on the matter seems to drastically change after an illness that year.

In a November 20, 1833, letter to his son Rush, Norcom reflects on his recovery from an illness that had left him debilitated, noting that he has greatly improved by the "favor of God." He writes:

"My dear Rush, this affliction, though severe, yet it has been of immense value to the interest of my soul. I have, I sincerely hope, realized the entire necessity of absolute dependence upon the mercy of God and upon the merits of his beloved son Jesus Christ."

November 20, 1833, letter from Norcom to his son Benjamin Rush ("Rush"). Letter 171 of the James Norcom Family Papers.

Similarly, in a letter to his son Caspar Wistar on September 25, 1834, Norcom encourages him to live a religious life. He assures Wistar that he does not wish for him to lead an irreligious existence, despite any doubts he may have expressed in the past: "The wisest, the best, & the greatest of men have been Christians, and have been the friends & patrons of religion." He encourages Wistar to "never allow yourself to be concerned in any act tending to throw ridicule, reproach, or odium on any regular authorized form of religious worship."

September 25, 1834, letter from Norcom to his son Caspar Wistar, in which Norcom encourages him to live a religious life. Letter 199 of the James Norcom Family Papers.

As Richard Rankin observes, "If his conversion was insincere, he was a gifted actor." Although that does not preclude what Jacobs writes about their conversation on the topic; Norcom was a master of saving face, including with his family.

Norcom is buried in the St. Paul's Episcopal Churchyard in Edenton.

Gravestone of Dr. James Norcom at the St. Paul's Episcopal Churchyard in Edenton. Uploaded to findagrave.com by CindyS.

Click here to read about Norcom's involvement with Freemasonry.

0 notes

Text

"She clasped a gold chain round my baby’s neck. I thanked her for this kindness; but I did not like the emblem. I wanted no chain to be fastened on my daughter, not even if its links were of gold."

0 notes

Text

My mistress had taught me the precepts of God's Word: "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself." [Matt 22:39b] "Whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so unto them." [Matt 7:12a] But I was her slave, and I supposed she did not recognize me as her neighbor.

Harriet Jacobs (from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Chapter I)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

But this is an old-new sonority's old-new complaint and Miles, like Jacobs, keeps going past such emancipation by way of a deeper inhabitation of the song that makes it seem as if he were young again, as if embarking for the first time on the terrible journey toward some new knowledge of (the) reality (principle), the new knowledge of homelessness and constant escape.

from Black and Blur by Fred Moten

#Fred Moten#Black and Blur#Miles David#Harriet Jacobs#Black art theory as an excavation of meaning#Black radical theory#Black sonic vortex

3 notes

·

View notes