#HUM4938

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

LGBTQ+ History Tour | HUM4938 | Excursions

with Queer Tours of London

Following the steps of three activists from different phases of LGBTQ+ expression and community development, Stuart Feather, Dan Glass, and Lyndsay Burtonshaw, we explored a series of landmarks in central London significant to the Gay Liberation Front of the 1970’s, and received an intergenerational perspective of how these places and the queer community of London thereof, have changed.

2017 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the (partial) decriminalisation of Homosexuality and Abortion in the United Kingdom, through the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. Despite a strong resurgence of fundamentalist christian values and relatively conservative ideas surrounding the two subjects, The Royal Courts of Justice granted assent to the law on July 27th, and it was passed. Although it was a much needed foundation for further activism, many of the rights that LGBTQ+ individuals hold today were still not supplied through this act—the age of consent was higher for homosexual relationships, and following legislation prevented the universal social acceptance of homosexual relationships and families, by restricting educational projects and materials and funds or resources that might be used for community learning.

This legislation, known as Section 28, passed in 1988 and rescinded in 2003, shaped the way queer people, especially queer youth, viewed themselves in respect to their community, by reinforcing the restrictive values that opposed the Sexual Offences act in the first place. A large part of queer identity (and identity in general), after all, is the accessibility of knowledge and understanding of those identities, populations and spaces (not only virtual but also physical) where those ideas can be exchanged. The fear associated with open expression as instilled by Section 28 catalysed the potential growth of queer spaces, and still today almost two decades after its acquittal, its effects are present, in the lack of disability, youth (see: Project Indigo), and permanently accessible centres.

Regardless, prior to any of these laws being passed, any sexually “deviant” behaviour remained illegal, and was entirely disparaged by British Society. Stopping by the ‘Notorious Urinal’ on Strand Street, a site which is now an sub-street cabaret club, underground gay culture was explored. Here, and in other urinals, bathrooms, (“tearooms” by the american standard) and public spaces of interaction, affection—cruising (not illegal) and cottaging (illegal) took place. To avoid being caught with their gay partners in the restroom, one individual might stand in a shopping bag behind the stall, to hide their feet. In movie theatres, like the Lyceum nearby, certain aisles were designated by Gay men, as those that could be used as places for meeting one another. A new subversive pseudo-language, really a cant-slang, Polari, emerged in the gay subculture in the earlier half of the twentieth century, mixing with other groups by the sixties (the drug subculture, to be frank), and influenced how Gay men in particular interacted. They could not be open, for fear of criminal prosecution, or hate crime.

The villainisation of homosexuality continued past the Sexual Offences Act of 1967, in quite seemingly innocent ways. Although the queer community had come out of the closet and into another world of what it meant to have a different proclaimed identity, their world was far from mainstream, and protested, at that. To make a stake of their own, two sociology students, Bob Mellors and Aubrey Walter, founded the Gay Liberation Front in 1970, inviting queer men and women (and those in between) to end discrimination against the homosexual community in the workplace, education, medicine, and society (Feather, 30). The front soon faced various issues in its community. Less than a year after its founding in 1971, a book related to sexuality, entitled Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex…But Were Too Afraid To Ask by American Psychiatrist Dr. David Reuben, which completely ignored homosexual relationships except in mentioning the predatory, insatiable sexual nature of gay men and frivolity of Lesbianism (in that it was directly related to proclivity towards prostitution) rose to popular acclaim, becoming a best seller in the States. Upon the news that the book would be published through local company W H Allen, the Gay Liberation Front’s Counter-Psychiatry group petitioned against its release upon the grounds in a letter to the publisher that it was “pernicious and dangerous rubbish,” showing ���obvious claims for those [the author] wishes to help.”. W H Allen proceeded with circulation, and more active protest took place. Demonstrations with street theatre groups were staged, book shop displays were trashed, and in the books that were left alone, pamphlets sat in between the pages, warning readers of misleading material (Feather, 130-133). The medical community still did not treat queer individuals as entirely healthy, or with the same concern as straight patients: as homosexuality was still seen as a mental illness, in some ways, healthcare was stigmatised, and limited (this stigmatisation most definitely contributed to less sex education, and led to the AIDS crisis of the 80’s and 90’s, the spread of STDs, and, today, a role of drug dependence and higher rates of mental illness in queer individuals). Standing in front of the brick townhouse formerly home to W H Allen Publishers, surrounded by the remaining promotional material for the PRIDE parade but a day earlier, it was hard to imagine that such blatant disrespect for the community would have taken place—but so is time and social change, that begins to erase our conceptualisation of possibility of behaviours from years prior, yet so is the reclamation and recovery of a society, that hides its shameful past.

Most of the places we visited had changed in the fifty years between the Sexual Offences Act and today—London is, after all, an amazing city, prone to change, growth, and the moving of shopfronts, landlords, and patrons. A negative to this effect, is the lack and closure of queer physical occupation, in part due to the immense growth of the business district and real estate sector, mostly due to gentrification. A quarter of LGBTQ+ spaces in London have closed in the past three years, and new spaces (especially those accessible to target groups mentioned prior) struggle to pop up and stay afloat (there are currently no Lesbian-only spaces in London). Thankfully, a few iconic sites still remain. Of those, we visited Heaven, a nightclub and bar in Charing Cross, that not only is a place to get together and party, but also to discuss community and safety (offering HIV/AIDS and STD testing, hosting community education events and speakers, and staying open for those who might feel more secure in their walls). Club culture is a large part of the LGBTQ+ culture, in full. Clubs are places of love, and acceptance, and celebration of one’s sexuality and identity attached. So many subcultures of the LGBTQ+ pop scene, including Drag (pageant and club especially), dance, and music (George Michael, anyone) emerged from the festivity, coming to full fruition in the space itself. Lyndsay mentioned the Bell, a nightclub from before her generation of activists that has since been closed, but housed a similar ambiance. Nowadays, the feeling of acceptance often can be accessed by interaction through the internet. Digital spaces for queer people, especially youth, are becoming all the more relevant and significant to the growth and activism of the community. Unfortunately, digital spaces cannot always make up for the benefits of physical spaces, but nonetheless, are essential to contemporary discussions of queer existence and occupation, and, due to advances in technology and social media, hold the potential to streamline and strengthen events in activism.

Pride in London, originally a protest in 1972, was depoliticised to a parade in 2004 (read more here in my post about 2017 PRIDE in London). But it was not the only event that was orchestrated to rally for the rights of LGBTQ+ folk by any means. In coming to Trafalgar Square, and later, situating ourselves on the fences of Whitehall (home of current Conservative party leader Theresa May, who has historically opposed queer rights), we were told the kinds of more ‘revolutionary’ if you will, forms of protest. Most involved the reclamation and re-appropriation of slurs or derogation—like mass kissing, or just a large gathering of Gay people in an area kissing one another where one couple may have been discouraged by a passerby, indicating the reclamation of that space not as one of intimidation, but security. To riot or protest is not to simply make noise, but to make express notice of your embodiment of a person, and those other people like you. We were told by Stuart about the GLF’s youth organised rally in Hyde Park in 1971consisting of ~1000 individuals, who went down Oxford Street and effectively began the roots of the pride parade, and ‘Operation Rupert’ an interruption of an evangelical christian conference, ‘The Festival of Light’ in early fall later that year, in which groups dressed as nuns and Klu Klux Klan members to caricature the attendees, released mice and stink bombs, and released banners intermittently throughout the initial ceremony, effectively disturbing the event and making a farce of the organisation, Dan’s remark of a 2015 march made on the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall called “RIP Pride,”, an effective funeral to note and condemn the now pink-washed parade, and to honour the original radical roots of the protest.

At both the start and end points of the tour, Dan reminded us that “we cannot let activism be coopted,”. Needed words in a city, a society, with strong capitalist influences, new cultural appropriation of social justice, and a turbulent political near-future with the approach and execution of Brexit. Queer history and existence, as any minority record, is ingrained in the history of London, and the politics of the United Kingdom today. What the Gay Liberation Front stood for in 1970, in solidarity with the queer community and other races, so does the contemporary LGBTQ+ activist today, with added emphases on the rights of immigrants and refugees, and safety of queer individuals not just within the bounds of one’s city or country, but in the rest of the world.

Sources and Further Reading

A quick read about gay rights in the UK

The Polari Language

Queer Tours of London

Stuart Feather, Blowing the Lid: Gay Liberation, Sexual Revolution, and Radical Queens (find his book Here)

#activism#queer history#lgbtq history#excursions#hum4938#queer tours of london#stuart feather#london#gay history

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Philip Venables & David Hoyle Illusions | HUM4938 | Excursions

Illusions by Philip Venables at the festival of New Music Biannual was an enthralling introduction to the contemporary composition scene in London, as well as a much-needed thrust into the relevant discourse of the LGBTQ+ community to get a gauge on queer issues in British culture, only a day after the PRIDE parade, which was a display of the happier, joyous side of the culture, the celebration that was only happening because of the depoliticisation of the event, diminishing the protest to a parade. This performance was in stark contrast to that environment. Venables, who also is a part of the community, has received acclaim for his work focusing on sexuality and political themes, and this piece certainly did not fall short.

Combining the cacophonous noise of a sinfonietta, the brash ideas of avant-garde drag performer David Hoyle (known by pseudonym “Divine David”) in a stream of consciousness, and a soothing but quirky "elevator music" bossa nova, Venables delivered a hard hitting video-audio commentary into the thought of the average British Queer individual, in four movements:

democracy: the role of democracy in queerness,

gender: how one would begin to learn of their identity (and the struggle involved therein, of finding appropriate jargon and space to realize it),

assimilation: the political influence and repression of queer culture, and

revolution: against that political influence.

It wasn't really made as a piece of talking to any member of the LGBT community, although there were some asides made to people who identified so—it was largely not a rant but a passionately intellectual (albeit, rather polarizing) and a little bit condescending, although comedic, statement to those who are not a part of the community, or rather opposed to it (the conservative parties, or minded individuals).

David’s dialogue was not the parameter by which the music took place—it was not speech sound, by any means: the orchestra took on the rhythmic constancy of his video, and although they augmented the speech to a point, enunciating and emphasising certain fluttered repetitions in an almost post-apocalyptic overlapping big-top sound, the ensemble too provided a possible medium by which David’s words were muffled; as his cries to action grew louder, so did they (perhaps this was an issue of the technical variety, but so is live art; so is the experience of contemporary music and the projection of one’s inferences onto a presentation or work of art). Was the orchestra his foundation? His greek chorus? Or was it the very foundation he spoke against, the people he was speaking to, cluttering the message, interpreting it and dissecting it to their needs to distribute its message to their best advantage? Regardless of the role of the orchestra at a metaphorical level, I did enjoy their physical playing as well. The conductor, Richard Baker, was a perfect fit—his movements were percussive, distinct, yet embodied a postured grace and length to movements. My favourite sections of the sinfonietta were the strings, which often had legato sostenuto passages, sliding between notes in a taffy-like manner, still elastic, but providing a canopy over which the avant-garde Hoyle pronounced his qualms, but so too had double stopping, frantic jumps. I also enjoyed the role of the piano, and although I cannot pin point my exact attraction to its part, I do remember noting its presence, and the delicate yet pronounced, intellectual tone it brought to the conversation of the instruments. Brass and winds were overwhelming, I think to me as they always are, for their kind of louder, screeching qualities, but they were the characteristic of this piece, that which pronounced the offence, the effect of the words. The percussion was minimalist but lovely, providing a rumble, the electro-static underneath the tonal parts of the piece, keeping a rhythm and stopping only to blow the whistle between movements. Some parts of the piece weren’t live, but recorded. Aside from David’s video footage, a bossa nova track (which Venables described as “elevator music”) played in the sections before the entrances of the orchestra, often highlighting moments of condescension or humour throughout. Each movement came to its own climax, but most certainly, the hardest hitting crescendo was that in the third movement, queer assimilation, when Hoyle explored the concept of human beings having to demean themselves in an act of subjugation, “to beg for the right to be themselves,”, condemning any person who directly denies others the right and the dignity (or even supports the system that upholds it) of being themselves in the first place. The music became more and more frantic, dissonant, and pleading.

In the same way that Hoyle was protesting traditional or conservative ideas of gender and identity or political control of personal expression, so was Venables against the ideas of traditional, conservative music. Music, in comparison to the other art forms of theatre, dance, creative writing, sculpture and 3D art and two dimensional fine art, is a very conservative field. As a music major, and as a dabbler in music education, unless in the field, in an area where the teachers are experienced or come from similar schools, there is often a lead by younger students and even those in the profession that more strongly and vehemently defend traditional ensembles and genres than new popular and contemporary forms of compositions. So often do we exclude or deny digital music or popular genres of their legitimacy in academia, in the profession, that we alienate ourselves from the majority of musicians today (who are amateurs or self-taught, not involved in academia, and thoroughly or even casually entrenched in more exciting, faster moving, progressive areas). Music pedagogy (and education in general) in the UK is far more progressive, and to see these kinds of themes persist to acclaim here, was encouraging, to say the least. It might be rather obvious, but to see the parallel between the conservative art form of music to its fellow forms, to conservative politics and values to a population, was personally significant. I enjoyed the composer’s commentary on this part, and his further note that some musicians prefer to look at music as just music; an aesthetic, not a political vault. However, as an art form, it exists for expression, and should be encouraged as a medium for communication of these values.

Moreover, I realized sometime during the interview and the second performance of the piece, that this was not just only a testament to gender expression as a political issue, but also an affront to what offence really meant. Of course, there was a quote from Philip that I think rang true to the audience and stood out from his interview, that "If you’re more offended by a performance than the offensive concepts, then there is an issue,”, which is certainly true. But I think the entire perception of the offensiveness and abrasive qualities of the performance, although it was dissonant and chaotic, kind of lie in the mistaken understanding of what intended offence would be. As, to some extent, the purpose of the composition was not to offend, but to speak to a larger issue, to engage. In social justice communities, and especially in the queer community, calling people out for negative or mutually detrimental behaviour is a common phenomena, essential to positive discourse. What is called “tea” or “shade” or “drag” or whatever have you is simply a nod to expecting others in your community, in your diaspora, to cease withholding toxic behaviours and opinions often instilled by assimilative systems. To correct someone, to plea for their needed involvement and awareness, acceptance, is not offence, and should not be taken so. It is a necessary part of the conversation. To be corrected, very blatantly is to be loved, to be cared for, and invited into the discussion, and although at some times it can be seen as aggressive, being as informed and as unproblematic (or, moreso aware of your problematic tendencies, privileges, and effects on your perspective) as possible is to be a proactive member of discourse on any given subject, especially in scenes of rights, and of expression. It was an abrasive performance, absolutely—to downplay the inherent anger of the LGBTQ+ community in making these remarks would be to miss the point of the piece entirely. But I hesitate to call it even potentially offensive to those who are not in immediate agreement with Hoyle or Venables.

If possible later on, I would like to hear the recorded version of the piece, if it does change from the live performance, and how that effects the interaction between the pre-recorded material featuring Hoyle and the music of the ensemble.

sources and further reading: Illusions - Philip Venables & David Hoyle Interview with Philip Venables about Music, Violence, and Text

#Queer art#LGBTQ#Philip Venables#new music#contemporary music#David Hoyle#Illusions#excursions#HUM4938#usf in london

1 note

·

View note

Text

Discussion Posts

Text for my guided excursions! As all posts aren’t yet finalized to complete report, here are the basic blurbs made for each.

Guided Excursion 2: Illusions

Illusions by Philip Venables at the festival of New Music Biannual was an enthralling introduction to the contemporary composition scene in London, as well as a much-needed thrust into the relevant discourse of the LGBTQ+ community to get a gauge on queer issues in British culture, only a day after the PRIDE parade, which was a display of the happier, joyous side of the culture, the celebration that was only happening because of the depoliticisation of the event, diminishing the protest to a parade. This performance was in stark contrast to that environment. Venables, who also is a part of the community, has received acclaim for his work focusing on sexuality and political themes, and this piece certainly did not fall short. Combining the cacophonous noise of a sinfonietta, the brash ideas of avant-garde drag performer David Hoyle (known by pseudonym “Divine David”) in a stream of consciousness, and a soothing but quirky "elevator music" bossa nova, Venables delivered a hard hitting video-audio commentary into the thought of the average British Queer individual, in four movements: democracy: the role of democracy in queerness, gender: how one would begin to learn of their identity (and the struggle involved therein, of finding appropriate jargon and space to realize it), assimilation: the political influence and repression of queer culture, and revolution: against that political influence. It wasn't really made as a piece of talking to any member of the LGBT community, although there were some asides made to people who identified so—it was largely not a rant but a passionately intellectual (albeit, rather polarizing) and a little bit condescending, although comedic, statement to those who are not a part of the community, or rather opposed to it (the conservative parties, or minded individuals). David’s dialogue was not the parameter by which the music took place—it was not speech sound, by any means: the orchestra took on the rhythmic constancy of his video, and although they augmented the speech to a point, enunciating and emphasising certain fluttered repetitions in an almost post-apocalyptic overlapping big-top sound, the ensemble too provided a possible medium by which David’s words were muffled; as his cries to action grew louder, so did they (perhaps this was an issue of the technical variety, but so is live art; so is the experience of contemporary music and the projection of one’s inferences onto a presentation or work of art). Was the orchestra his foundation? His greek chorus? Or was it the very foundation he spoke against, the people he was speaking to, cluttering the message, interpreting it and dissecting it to their needs to distribute its message to their best advantage? Regardless of the role of the orchestra at a metaphorical level, I did enjoy their physical playing as well. The conductor, Richard Baker, was a perfect fit—his movements were percussive, distinct, yet embodied a postured grace and length to movements. My favourite sections of the sinfonietta were the strings, which often had legato sostenuto passages, sliding between notes in a taffy-like manner, still elastic, but providing a canopy over which the avant-garde Hoyle pronounced his qualms, but so too had double stopping, frantic jumps. I also enjoyed the role of the piano, and although I cannot pin point my exact attraction to its part, I do remember noting its presence, and the delicate yet pronounced, intellectual tone it brought to the conversation of the instruments. Brass and winds were overwhelming, I think to me as they always are, for their kind of louder, screeching qualities, but they were the characteristic of this piece, that which pronounced the offence, the effect of the words. The percussion was minimalist but lovely, providing a rumble, the electro-static underneath the tonal parts of the piece, keeping a rhythm and stopping only to blow the whistle between movements. Some parts of the piece weren’t live, but recorded. Aside from David’s video footage, a bossa nova track (which Venables described as “elevator music”) played in the sections before the entrances of the orchestra, often highlighting moments of condescension or humour throughout. Each movement came to its own climax, but most certainly, the hardest hitting crescendo was that in the third movement, queer assimilation, when Hoyle explored the concept of human beings having to demean themselves in an act of subjugation, “to beg for the right to be themselves,”, condemning any person who directly denies others the right and the dignity (or even supports the system that upholds it) of being themselves in the first place. The music became more and more frantic, dissonant, and pleading. In the same way that Hoyle was protesting traditional or conservative ideas of gender and identity or political control of personal expression, so was Venables against the ideas of traditional, conservative music. Music, in comparison to the other art forms of theatre, dance, creative writing, sculpture and 3D art and two dimensional fine art, is a very conservative field. As a music major, and as a dabbler in music education, unless in the field, in an area where the teachers are experienced or come from similar schools, there is often a lead by younger students and even those in the profession that more strongly and vehemently defend traditional ensembles and genres than new popular and contemporary forms of compositions. So often do we exclude or deny digital music or popular genres of their legitimacy in academia, in the profession, that we alienate ourselves from the majority of musicians today (who are amateurs or self-taught, not involved in academia, and thoroughly or even casually entrenched in more exciting, faster moving, progressive areas). Music pedagogy (and education in general) in the UK is far more progressive, and to see these kinds of themes persist to acclaim here, was encouraging, to say the least. It might be rather obvious, but to see the parallel between the conservative art form of music to its fellow forms, to conservative politics and values to a population, was personally significant. I enjoyed the composer’s commentary on this part, and his further note that some musicians prefer to look at music as just music; an aesthetic, not a political vault. However, as an art form, it exists for expression, and should be encouraged as a medium for communication of these values. Moreover, I realized sometime during the interview and the second performance of the piece, that this was not just only a testament to gender expression as a political issue, but also an affront to what offence really meant. Of course, there was a quote from Philip that I think rang true to the audience and stood out from his interview, that "If you’re more offended by a performance than the offensive concepts, then there is an issue,”, which is certainly true. But I think the entire perception of the offensiveness and abrasive qualities of the performance, although it was dissonant and chaotic, kind of lie in the mistaken understanding of what intended offence would be. As, to some extent, the purpose of the composition was not to offend, but to speak to a larger issue, to engage. In social justice communities, and especially in the queer community, calling people out for negative or mutually detrimental behaviour is a common phenomena, essential to positive discourse. What is called “tea” or “shade” or “drag” or whatever have you is simply a nod to expecting others in your community, in your diaspora, to cease withholding toxic behaviours and opinions often instilled by assimilative systems. To correct someone, to plea for their needed involvement and awareness, acceptance, is not offence, and should not be taken so. It is a necessary part of the conversation. To be corrected, very blatantly is to be loved, to be cared for, and invited into the discussion, and although at some times it can be seen as aggressive, being as informed and as unproblematic (or, moreso aware of your problematic tendencies, privileges, and effects on your perspective) as possible is to be a proactive member of discourse on any given subject, especially in scenes of rights, and of expression. It was an abrasive performance, absolutely—to downplay the inherent anger of the LGBTQ+ community in making these remarks would be to miss the point of the piece entirely. But I hesitate to call it even potentially offensive to those who are not in immediate agreement with Hoyle or Venables. If possible later on, I would like to hear the recorded version of the piece, if it does change from the live performance, and how that effects the interaction between the pre-recorded material featuring Hoyle and the music of the ensemble. sources and further reading: Illusions - Philip Venables & David Hoyle (Links to an external site.) Interview with Philip Venables about Music, Violence, and Text (Links to an external site.) This post is also available here

Guided Excursion 3: Queer Tours of London

Following the steps of three activists from different phases of LGBTQ+ expression and community development, Stuart Feather, Dan Glass, and Lyndsay Burtonshaw, we explored a series of landmarks in central London significant to the Gay Liberation Front of the 1970’s, and received an intergenerational perspective of how these places and the queer community of London thereof, have changed.

In particular, we touched on the issue of visibility and accessibility of queer spaces (the change from clandestine underground languages such as polari and covert interactions such as cottaging/cruising, to open and active resistance and pride, and current open discussions about queer spaces, as well as the political influence ie section 28 and its effect on queer expression, and the relationship between digital and physical places of connection), the extensive stigmatization of the homosexual community at length (discussing the issue of W.H. Allen's publication of a homophobic book on sex, lack of existence of Lesbian-specific spaces in general, but very little about bisexual, trans*, or others), and the history of activism and revolution in the LGBT community (which was augmented certainly by each of the guides, although Stuart was an original member of the GLF in the 70's--more discourse about PRIDE as a protest, pinkwashing, trafalgar square, interrupting fundamentalist christian conferences, and contemporary issues, standing in front of Whitehall, the home of Theresa May, who still is relatively homophobic).

I was surprised that even in such a large city as London, LGBTQ+ community spaces do not exist in permanence--and Lesbian resources, in particular, are even less common.

Guided Excursion 4: Brick Lane

The development of Art into popular market has historically, almost always encountered a delay of interest. There are mini paradigms, so to say, of what is considered aesthetically acceptable, let alone politically acceptable to portray, which is why many of the famous artists after the classical period, members of movements that seemed to be underground and under published, received far more posthumous acclaim than when they were living—Van Gogh is a prime example, as is Vermeer, Monet, Cezanne, Manet, and countless others. Recently, the half lives of pop culture seems to have become less and less lengthy, in the interest of entertaining new art forms, and perhaps too, in the interest of catching up to the forefront of artistic movements, something that is now possible in a digital age.That chase is especially relevant in the streets of East London today, where yet another marginalised form of artistic expression, graffiti writing (and the distilled street art), faces both vehement prosecution and pointed interest. Despite the fact that the artists themselves are usually youth (and usually, men) influenced by the culture itself, already marginalized and potentially harassed for their expression (as artistic, sensitive fields are not gendered towards boys growing up; graffiti and hiphop, in a way, are reflections on the artistic cultures of men, an attempt at expression through the filter of masculinity) The off-gassed physical expression of hip-hop culture is at the crossroads of the popular market, appreciating or appropriating the works, and a system that finds it still too revolutionary to the paradigm of acceptable aesthetic and political contemporary expression. Although graffiti and street art have both been widely appreciated elsewhere, in the states, and even on a global scale supported to a wide degree (artists like Shepherd Ferry “OBEY”, Invader, Ronzo, Banksy, etc are internationally recognised and make quite a lot of money from the overground market), the place where individuals still seek to express their original ideas in the form of the original art is restricted. In part, because of the clash between the historically socioeconomically displaced neighbourhood there, and the growth of an illustrious business district that, understandably, seeks to expand. Not by adoption of the community, but by appropriation of the popular community inter actives and gentrification of the areas surrounding. On its side is the police and local government, which still holds graffiti artists accountable for up to £2,500 or 10 years in prison (if above the age of majority) or two years for minors age 12 to 17, under section one of the criminal act of 1971, regarding criminal damage and prosecution. That being said, not all sites are illegal to tag (Star Yard is one of those grey-areas, an open gallery)—but with increased security brought on by the financial district, and more pressure, financially, for surveillance to take place, the original significance of graffiti, to tag and write where the artist wanted as a means of communication with other artists, becomes harder to do. That is, unless you’re commissioned or sanctioned to paint a piece—which changes your status from public enemy, to public servant. Larger pieces seen down fashion street or in Eli’s yard, painted or installed by more mainstream or popular artists. A local artist might too be asked to paint a local business’ building, but when this art piece becomes a permanent installation, the form of art changes, from Graffiti, and street art, to something else. This implies a kind of sanctity to street art that isn’t necessarily a part of the original intent of the form. Graffiti and street art are recyclable—they’re a form of communication, after all. When someone tags, it stays until someone else can cover it with theirs, in a more elaborate way (as to show respect—a simple tag or stencil that interrupts the piece might not be the best idea)—it evolves. When a piece is worn down, another artist can build on top of it. But the newfound culture of appreciation of graffiti, of interpretation and projection of meanings that might not necessarily have been intended, is a part of the popular art culture (of museum art culture) that simply seems alien to street artists. Upon encountering a piece by artist Stik, who is of some relative popularity, we were told that he’s on occasion asked to return to the particular piece to touch it up and restore it—something that is never really thought to happen. In protest, a few other artists (including the main one in silver, Sony) have tagged over it—not in disrespect to Stik, so to say, but to those that keep the art up when it’s meant to expire—the tourists that apply themselves to the culture of capitalisation and gentrification that is threatening the art form in its place.

Guided Excursion 5: Seven Sins Cabaret

Cabarets are infamous for impromptu and enthralling performance—even moreso as their roots lie in risqué and raunch characteristic of saloons, bars, and the red light district of Paris at the turn of the twentieth century. The Café de Paris exemplified that atmosphere, embodying the lush and dark and extravagant setting that would be a vaudeville-era club owner’s take on the circles of hell. The show opened with a vibrant introduction from the house emcee, drag performer extraordinaire, Ruby Kaye, who entered in a bedazzled priest robe, smoky eye, and glittering lips. It was clear that the performance to follow would be a company of different but all the same extravagant, agent dancers and acts that presented seductive and powerful versions of their sins. I’d been a part of theatre before, but it’s been a while since I’d partaken in Cabaret (any theatre is really an interactive experience, never just a show, but the nature of Cabaret is far more intimate). The show spoke to so much more than a spectacle of performers—it was empowerment, ownership of sexuality, through acts that stretched the limits of what it meant to be envious, gluttonous, greedy, wrathful, lustful, sloth, or proud. When I tagged Ruby in an instagram post, they responded “Perform, Educate, Empower!” and I think that was really the takeaway from this entire experience

Guided Excursion 6: V&A LGBTQ+ Tour

the V&A contains the largest collection of artworks in England, with pieces sourced from local artists and nationally renowned creators to individuals from its previous and current territories and commonwealths and countries beyond. Not only are there paintings and two dimensional works for aesthetic and historic value, but also culturally significant statues, sculptures, models, jewellery, metallurgy, and functional furniture, jewellery, pottery & ceramic and stoneware, and more. It comes to no surprise that there are at least a few LGBTQ+ artists works on display in the museum, and even less of a surprise that there are culturally significant works from queer activist movements. With the fiftieth anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act on the horizon, and PRIDE just behind, the Victoria and Albert museum’s housing of these works and artists has become all the more relevant. We started in the hall that housed a variety of plaster sculptures made of moulds of the greater works in history, standing at the feet of Michelangelo’s David, and were explained the main parameters by which artworks may be considered significant LGBTQ+ works, which in brief, fall under three distinct categories:

if there are obvious homosexual or queer themes that are apparent in the work,

if the creator identifies as an LGBTQ+ individual, either openly or in historic documents, OR

if the piece has been assumed or reappropriated by the LGBTQ+ community or various movements.

David, in particular, was a representative of all three. Not only is Michelangelo regarded as a gay figure in history, but so is david, in literature. We continued from pottery focused on queer and punk iconography, to a japanese lacquered screen made by Eileen Gray, a bisexual woman who became a part of a queer artists collective at the turn of the twentieth century in Paris, to artworks featuring imagery of Sapho (famously known for homosexuality), modern art reflective of the AIDS crisis and acceptance of homosexuals before complete decriminalisation, iconography of recent movements involving liberation of minority groups that directly intersect with the issues of LGBTQ+ movements today: the 2016 olympic refugee flag, the design of the burkini (important for the widespread acceptance of muslim women & their agency), nude heels (multi-racial representation), among others, concluding the tour in the theatre collection, surrounded by the props, costumes, and artefacts representative of a place of expression and security, that inspired and held so many queer performers in its ranks. The tour was not the most intriguing of all the excursions, as the V&A, although filled to the brim with artworks probably rich in queer history, we only stopped to see a few—I think in part due to the pace and separation of our group, which due to the size, wasn’t the most efficient in moving, or in gathering around exhibits. It was harder to hear, and had the groups been split up, there might have been time to see more or have a more in-depth conversation about the relationship between all of the artworks pointed out, or the historic art movements that prompted their craft.

Sources & further reading

Eileen Gray http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/e/eileen-gray/ (Links to an external site.)

Michelangelo http://www.uis.edu/lgbtqa/michelangelo/ (Links to an external site.)

V&A LGBTQ tour http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/va-faces/why-the-va-gay-and-lesbian-tour-is-essential

Guided Excursion 7: Rock N Roll Tour

The twentieth century and arrival of the new popular genre (started by the african american diaspora as those individuals began to gain and fight for community spaces in the United States) was an effective revitalization of Britain's prowess in the world of music, comparable degree of Handel in the Baroque. In years prior, especially during the romantic era, French, German, and Italian musicians came to show the essential properties of the movement, but the wave to come in the 1960's through 80's would so too redefine popular musics, and the personalities and variance of identities that would make it up. From Beatles to Bowie, Pistols to Pink Floyd, Elton John, Rolling Stones, and Queen, the Rock N Roll tour of London explored both the streets and significant sites where these icons made their mark, and the very meaning of icon as it came to be in a new century of marketing and managing, setting new standards in show-business, producing the "image" of talent. This new portrayal, subject to the press and public attention, opened doors to new venues of creative and personal expression. Living such public lives, these musicians and showmen made statements on and off the stage. Private accounts and affairs were no longer so, and everything became objective—habits, performance—relationships. Sexuality and sex appeal contributed to certainly the success of these stars in a changing, more welcoming culture, but also changed the culture itself. When an artist used this venue to express a change, especially a deviance from social norm, it would generate media, support & disdain (attention is attention) and perhaps most importantly, allow a means of identification for queer youth (punk movement especially, but present in brit rock especially), and the normalization and destigmatization of queer culture.

0 notes

Text

Living in the Illusion: Queer expression and relationships between fiction and physical spaces and representation

My portfolio (and effective final) for HUM4938: Media, Power, and Sexuality. In abstraction, an analysis of the role of media in portrayal and/or realization of queer characters and spaces, and its relation to the constructed fictionalization/stigmatization of queer people in real life.

Introduction

On June 24th, I landed in London. It was my first time outside of the United States, and an opportunity to study and learn a new city, a new culture outside of my own, and of course, explore my own relationship to that. But I was a student, first and foremost. I spend my week studying, going from class to class, to excursions and museums and parts of town I couldn’t even dream of finding on my own. As the days went on, so more did I see new prismic projections down the streets and up the escalators of the underground, peering through at tube stations and in coffee shops and in the alleys of Leicester square. The west end soon became a flurry of rainbows—the city, although already diverse and buzzing, was more and more colourful as it anticipated the arrival of the celebration of freedom of expression of love.

Although I’d been somewhat involved in LGBTQ+ groups and discourse in my time in high school, and certainly had gone through moments of questioning my personal identity, I’d never been to a Pride parade, or any queer community event for that matter, before. I wasn’t sure if I was meant to go; at the time, and still currently, I identify somewhere between asexual and bisexual—a demi-bisexual. Since there’s some ambiguity among the members of the LGBTQ+ community about ace and bi individuals as to where they belong in representation, activism, and portrayal, it seemed a little difficult to throw myself in the mix. In any case, my preferences have never been evocative of any particular direction or affect, and I’d been hesitant to label myself, either in fear of being wrong, or perhaps in fear of being misunderstood, judged. Quite simply, I was never really sure if I was really queer enough, so I never came out.

And so, out of pure curiosity, and perhaps with a little sense of hopeful belonging, I went the second Saturday of my trip to London Pride—it was a special event, as it was the fiftieth anniversary of the partial decriminalization of Homosexuality: a civil rights benchmark that was so significant to the progress and acceptance of so many individuals in modern society. It was a colourful event, filled to the brim with unbelievable spectacles of love, joy, happiness, exuberance, glitter, rainbows, and what seemed to be absolute magic performed by drag queens and shown by endless seas of flowing rainbow-coloured fabric, flags flying down Oxford street, highlighted by a rugby player’s proposal to his boyfriend, furthered by the unending positivity between all those who attended. I felt an innate sense of grounding in camaraderie with the people surrounding me, in the crowd and on the parade route, that I never felt before, regarding sexuality and identity, really.

But it so too felt almost unreal—not only in the way that I was four thousand some miles away from home, but too because my understanding of LGBTQ+ history was that of struggle; up to this day. The presence of protest groups in the pride parade made a stark contrast to the parties surrounding—while the parade remained a spectacle, and celebration of what had been achieved, groups like stonewall and others were reminiscent of the original intent of pride; to make it clear that queer individuals existed, and should be treated as any other human being, through breaking that spectacle, and agitating others as to make sure they are heard, and change takes place (as Oscar Wilde noted, “That is why agitators are so absolutely necessary,”). The perfect, rainbow-coloured parade was manufactured by the many corporations that sponsored the event, and that “pink-washed” (and furthermore was a part of the depoliticisation of) what was once a political protest and communal event for demanding solidarity and equal representation. It was dismal to think, even at the back of my mind, that something so beautiful was at its foundation, (like many things) corrupt.

The day after pride, our class took an excursion to the new music biannual conference—or festival, I’m not too sure—it was the final performance of the series, a piece composed by avant-garde contemporary composer Philip Venables, featuring the London Sinfonietta and queer performance artist David Hoyle: Illusions (read more about this excursion here). It wasn’t exactly a speech pattern composition, but an orchestral interaction between parts of the text that elicited rhythm and meaning.

youtube

Although it is the title statement, one phrase did manage to stick out to me, after pride, and even continuing into further exploration of queer culture in London—Hoyle mentions of democracy in the current age (2015 was the original release of the piece, but Venables, in an interview between the performances, still noted its relevance two years later) “you know and I know it’s an illusion,”. The piece was addressed mostly to the new conservative government—but too was shown to those in attendance, ranging from any given socioeconomic class (but most likely, those who could afford a ticket were of middle or higher status) and sexuality or gender identity. So, which population experiences that illusion? Perhaps it is all those there at the moment.

This idea (moreso a conundrum) remained in my mind until now—and I thought I should explore the idea of illusion when it comes to the portrayal and understanding, as well as the identification of homosexuality and queerness in media.

Illusion (n.) - 1. a misleading image presented to the eye 2. the state or fact of being led to accept as true something unreal or imagined 3. a mistaken idea

The Illusion

So often queerness is treated as if it is illegitimate; perverse; a figment or fancy of the imagination. Homosexuality, although partially decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967 under the Sexual Offences Act, was only decategorized from major psychological association’s published texts as a mental disorder in the 1970’s—trans* folk were even more outspoken in the medical community, with gender identity disorder only leaving the volumes of the DSM-V in 2012. Being queer was to be mentally ill, and was to live in illusion, to the understanding of society.

But who truly lived in that illusion? To queer folk, their experiences were all but as real as any other. The fictionalisation, or rather, assignment to obscurity of homosexuality and queerness too fictionalised those individuals accounts and agency when it came to social action: it was (and still, to a certain extent is) harder for LGBTQ+ individuals to assert certain self-evident rights in many situations. That fictionalisation too worked against them, when they were victims of continued cultural persecution, legal prosecution, and violence from various outlets. The stigmatisation of the community and of homosexuals in media, and the cultural paradigm that had existed prior to legal decriminalisation created a heavy ideal that, still today, continues to threaten even the basic levels of hierarchical need of queer individuals, forcing them to live “in the closet”, diminishing personal mental health and relationships, fostering subversive and possibly dangerous ways of life (queer individuals more prone to homelessness, drug use, contracting STIs, prone to domestic and direct violence), taking away access, or not deeming necessary, social resources, all caused by accepting queerness as fictional, and denying the existence of quite a large portion of the population, dismissing them as unreal.

It’s no wonder, then, that queer individuals have become so accustomed to their lives being called fiction—as they have produced some of the most intricately creative pieces of artwork, literature, and music, that exist in the realm on the edge of stark, political, reality and sensual, blissful, scary, manic dream matter.

The Theatre

There is no secrecy in that the Theatre is a queer space. Not really that all people who work and live in the theatre scene are gay (as somehow, that’s become another stereotype in this weird world of ours)—but its one of the safest spaces for creatives who have different identities, historically. Among those dancers, writers, actors, and more, Vaslav Nijinsky (as discussed in the V&A Tour, post coming soon), Stephen Sondheim, on and on and on, furthermore, the material that comes out of the theatre is usually intersectional in its inclusion of different demographics, from race to identity to sexuality, and there are so many queer cult classics from the theatre world: RENT, Fun Home, Belle Reprieve, etc. etc. etc. If I had to list all of the queer creators and significant creations in the performance world, I would probably not be able to write this piece.

The Theatre is also a place where illusion itself lives. The entire concept of the theatre is a space in which one experiences a suspense of disbelief: a temporary adoption of ideas or mindsets, settings and events that aren’t necessarily true. Whether through costume, set design, make up, technical design and lighting or the sheer action and verbiage of the script, plays, musicals, reveries, cabarets, and skits involve the audience and actors in a whole mirage of make-believe. This is important.

In London especially, theatre has played an active role in queer representation and activism, if not simply by being the space for those individuals, then by creating attention. Both Stuart Feather and Jill Dolan remark in their books about the involvement of Street Theatre in the movement for decriminalisation of homosexuality, and collaboration with the Gay Liberation Front in the 1970’s. The culture surrounding the theatre here, in the west end, as well as on Broadway, is one of avid acceptance of queer art.

A indication of that culture was alive and well in the Cafe de Paris—a nightclub and performance venue in Leicester Square, which our class visited later in the week. The performance that night was the Seven Sins Cabaret—a cabaret, of course, reminiscent of the red-light district, raunchy, and alcoholic gatherings of parisian businessmen in underground bars and performance venues, and the later production between Bob Fosse and Fred Ebb, which focused on sexuality and subversive performance culture in Nazi Berlin in the Kit Kat Klub. It certainly surpassed expectations (link to post coming soon) and was a pinnacle of scintillating, slightly erotic? but completely empowered performance. Upon posting to instagram, the emcee and director of the show, drag performer Reuben “Ruby” Kaye, commented on my post, still just as enthusiastic about the openness and the stark portrayal of sexuality, and the intimacy of performance and the way it helps shape ideas and removes hurtful stigma about open sexuality.

Later, I also had the opportunity (on the last night, no less--link to post coming soon) to go to the west end and see Kinky Boots at the Adelphi Theatre. I’d never seen the musical before, but I knew it was one of the quintessential pieces from the United Kingdom that deserved a look—as well as a significant LGBTQ+ representative production, as it focused on the friendship between the protagonist, Charlie, and his opposite story centre, Lola, a drag queen who helps Charlie navigate a difficult time in his life, dealing with the death of his father, and learning how to define himself as a man, as the Mr. Price of his family business Price and Sons.

Its an incredibly liberating and relatable piece—perhaps people don’t come to the theatre to see Kinky Boots if they aren’t open-minded already, but certainly, the older ladies in the row in front of me had a wild time at the show. The most impressive pieces to me, regarding identity and sexuality, are that of Lola’s pieces—first, “Lola’s World”, in which the lyrics read “Step into a dream, Where glamour is extreme, Welcome to my fantasy,” followed by the number “What a Man” in which the roles of gender are explored and reversed, and used to empower the performer. Of course, “Just Be”, too is a fantastic pride anthem, preaching for unlimited self expression. In the show, Lola is completely open about who they are and what they are, and what it means to be them, completely breaking any sense of deceit or illusion that goes along with being a performer, a person with two identities at face value.

A Stand Out: Todrick Hall

Aside from starring as Lola in the fall/winter 2016 season on Broadway, this openly gay creator has recently risen to a relatively popular stance in the performance world—both on stage (in Oz, Kinky Boots) and in television (as a recent host and choreographer on RuPaul’s Drag Race, the creator of Todrick MTV, and contestant on American Idol) by way of his YouTube channel, which he started in 2006. A decade later, Todrick has amassed over 2.5 million subscribers.

I found inspiration for this analysis in watching some of his videos, which feature his takes on pop culture classics, like Mean Girls, Disney films such as Alice in Wonderland, Beauty and the Beast, and plays (namely Chicago, as there are several cell block tangoes) and reimagines them as hollywood, gay, and black versions of the predominantly white, straight originals.

One that stood out especially, perhaps because of its magnitude as a project (it’s a feature-length video on his YouTube), is an autobiographical musical re-adaptation of the Wizard of Oz called Straight Outta Oz—the story closely following the narrative of the original, but in this version, Todrick is Dorothy, and his story is a reflection of growing up gay, growing up black, and navigating a technicolor world. These themes are directly related to the course’s parameters: it is media, and the power involved, and how sexuality comes into play.

youtube

(If you have the opportunity, skip to ‘Water Guns’ near the end of the video)

Following what Ruby Kaye imparted in her comment on my instagram post of “Perform, Educate, Empower,” Todrick fully explores what it means to be the content creator, producer, director, and performer of queer art and media made for the masses. His art takes the illusion, whether it be from the suspense of disbelief in the theatre, the makeup of drag queens, the use of music, or simply, the line between what is fictional in literature and real life, and applies it to a wholly human and enthralling experience, not necessarily to enlighten, but to ground—to create a common space that feels safe, welcoming, and intriguing, if anything. The fictionalisation which was used against him and other queer individuals is reclaimed in fantasy.

Creators like Todrick, who are now more able to express themselves in openly queer artistic choices, are not only the future of artistic production, but are also leading the way for progress in the destigmatisation of queer identity, diminishing the illusions of obscure gender and sexuality and making them known.

Conclusion

In 2016, the shooting at the PULSE gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, was exactly that: a display to make us realise that we were not safe. That to a certain extent, the LGBTQ+ community (especially the L, G, B) did live in an illusion of security. That we were still so far from acceptance. It only took so much hate (that had already existed, so evidently, yet that was shrouded by progress, by the spectacle of parade and celebration) to take away the lives of so many.

The line between what is real and what is illusory has always existed for the LGBTQ+ community. But for queer individuals, the distinction of either is all too clear. They are not the ones living in an illusion, but rather the ones working to shatter it.

References & Further Reading

Venables, P. (Composer), Hoyle, D. & London Sinfonietta, (Performers), Baker, R. (Conductor). (2017, July 9). Illusions. Live performance at Southbank Centre, London, United Kingdom.

Venables, P. (2015, September 19). Illusions. Retrieved July 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g4hJQimj45U

Ackroyd, P. (2015). Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day. London: Chatto & Windus.

Dolan, J. (2010). Theatre & sexuality. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Feather, S. (2016). Blowing the Lid: Gay Liberation, Sexual Revolution, and Radical Queens. Alresford: John Hunt.

Fierstein, H., & Lauper, C. (Writers), Mitchell, J. (Director), & Oremus, S. (Conductor). (2017, July 21). Kinky Boots. Live performance in Adelphi Theatre, London.

“Illusion”. 2017. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/illusion

Playful Productions. (2017). Kinky Boots [Brochure]. London.

Kaye, R. (Director). (2017, July 14). Seven Sins Cabaret. Live performance in Café de Paris, London.

Milazzo, F. (2016, September 12). Review: Seven Sins, Cafe de Paris. Retrieved from http://www.thisiscabaret.com/review-seven-sins-cafe-de-paris/

To contribute further to my research, if you are queer or identify in a way that you find different to cis- and hetero-normative tradition, consider completing this survey about your experience regarding the relationship between fiction, illusion, and queerness. Please follow, and if you’re keen on contributing, citing, or collaborating further to this research, send me an ask or submit!

1 note

·

View note

Link

Hello! I’m looking for LGBTQ+ input on my essay topic (Queer expression and relationships between fiction and physical spaces and representation of LGBTQ+ individuals) and relationship to those experiences! If you would like to take it, or give your input as a member of the community, please click on the link!

0 notes

Text

Brick Lane: The Power, Role, and Interpretation of Communal Art

By S. Brenneman, R. Brown-Campbell, C. Chapman, S. Faruzzi, A. Fritz-Muller, & C. Ramdhanie at the University of South Florida

In the boroughs of East London, across from the glistening towers of the business district on Liverpool Street, among the sweet-smelling vendors and merchants of Banglatown and the sparkling shopfronts of Spitalfields market, lies a forty-some year old relic of a culture constantly in a variant state of growth and change. It could be said that the streets themselves are the backdrop upon which such a strong community culture has grown, as there is no necessary permanence to the work there; but all the same, it remains integral to the identity of Brick Lane. Graffiti and street art are the medium of expression for artists in this community--inspired by hip hop culture, and reminiscent of similar movements from the 1970’s in New York and other American metropoli, it not only represents the landscape upon which it was sprayed, spread, or scribbled, or the individual artist’s social experience, but also is an indicator for the creative scene and differing community to come.

East London is not definitively a part of the City of London proper, but rather the area historically outside of Aldgate, on the ancient city’s borders. Although growth was slow, by the nineteenth century, a steady population had arisen in the area, due to industrialisation. The closest borough to City of London, Tower Hamlets, soon became known for its overpopulation and poverty, and concentration of minority groups, especially European Jews. Unfortunately, the neighbourhood faced more hardships in the turn of the century, in waves of crime (notably, the murders of Jack the Ripper), and mass bombings during the world wars that demolished a majority of infrastructure. Movements were made to rebuild, and, relocate—the docks and industries that provided interest in the area before had since deteriorated. The area did not receive any special interest again until the 1970’s, with an influx of Asian immigrants, and the development of docklands (to the business district known today as Canary Wharf) a decade later8. This is the height of the graffiti movement, and in an historically overlooked, ethnically diverse, and relatively economically disparaged neighbourhood, disenfranchised youth would find an outlet.

Tony Porter explains the struggle of inner city (and especially black) male youth in this similar situation: when placed in stressful social parameters, they run into the issue of the “Man Box”—a phenomenon of conflicting ideas of what it means to truly be a man, in relation to your surroundings and community9. In interest of pandering to masculine status, perhaps subversively doing so, these young men, like the young men in the states, turn to Graffiti, which acts as a kind of outlet of expression.

The Graffiti community is not simply about proving oneself worthy of being a man, but too, adversely, an artist (the pinnacle of sensitivity). Josh, (a graffiti tour guide) recalls his experience as a young man in the streets of East London, becoming an artist: “You have these young men, finding themselves in their adolescence, and hip hop culture, the arts, start to play a role,”. Once intrigued by graffiti, proving ones work is integral to belonging in the community. “If you can’t hang with the big boys, then you just have to work harder,”.

There is a system of respect and pride in skills. Like in any traditional art movement, each artist has their own style, preferred media (spray paint, stickers, chalk, crayons, etc) and pseudonymity, and plays into the changing piece that is the neighbourhood. Interaction is casual: pieces don’t need to remain (and rather, have an expiration date), so it’s okay to paint over other artists older or scrap pieces, bonus points to tag places harder to reach or where it might be illegal, and if a statement really needs to be made, an artist may simply scrawl a phallus over a piece (or artist, establishment) they dislike, eliciting the universal message of “fuck you,”.

To be a graffiti writer is to, as in any underground subcultural movement, exist in this semi-permanent margin of adolescence and adulthood, expression and dissidence. Unfortunately, the dissidence and adult aspects hold more weight in the systemic evaluation of the graffiti community, and artists are likely to be prosecuted for their (mostly illegal) craft. If an artist is identified in a particular act of defamation of property, depending on the degree of damage, an artist can receive a maximum of 10 years in prison if at age of majority, and up to a year in prison if a minor, according to the Criminal Damage Act of 1971, section one10. Although an outlet, graffiti writing, as a practice, is still a relatively risky art to get into.

However, through the years, with the ever-growing presence of social media and technology, significant impacts have been made to neighbourhoods like Brick Lane, and to artists who once painted their pseudonym on the backs of buildings for fun—the normalisation and fascination with urban art forms, as explored by popular artists in the later decades of the twentieth century (like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat) brought hip-hop culture and its coexisting forms (including graffiti) into a new age of overt expression. ‘Street Art’ became the new colloquialism for ‘graffiti’ and related arts, and gained attention, not only on the streets, but in museums, art schools, and oddly enough, the business world. Although not all graffiti writers are street artists, the transition from one to the other made more than sense—as street art became accepted, so did their work. As it became lucrative, so did their trade. On Brick Lane in particular, street artists have risen to a kind of local fame (this time, not only among their peers) in that they are allowed, if not commissioned, to paint pieces—portraits, murals, and otherwise—in the very spaces (shops, businesses, etc.) that once looked down upon the art form. The rise in aesthetically pleasing pieces, in combination with the historic reputation of the area, and the current societal obsessive trend with street art, wear (and to be quite blunt, appropriation or adaptation of street culture), has led to the creation of tours, which capitalise upon the fascination with the art form.

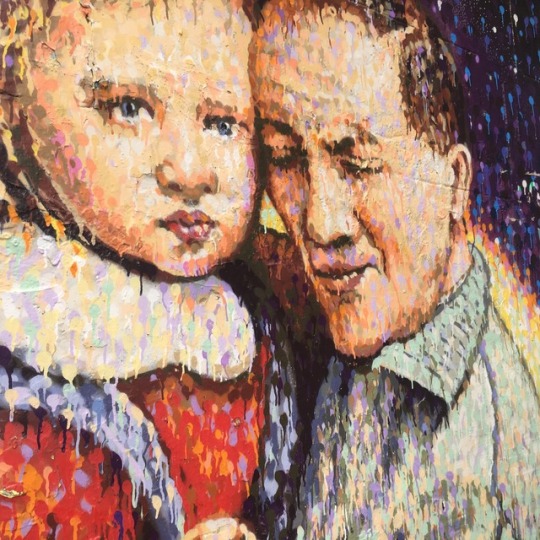

It’s a completely different culture than that of the London Graffiti of decades prior—instead of having expiration dates, pieces are digitally commemorated and effectively memorialised. A tourist posting a picture of a piece, whether it is illegal or commissioned/pardoned, contributes to a new culture of respect and reverence for not necessarily the artist, but the piece itself—a piece may even be furthermore curated in collections of now, culturally significant or emotionally/politically/artistically evocative pieces3. It’s not necessarily against the original intents of the artists involved—whereas graffiti writing was at its roots rebellious and political, street art has more flexible foundations: many artists paint murals, posters, or stickers for the sake of creating artwork, some to make a name for themselves, some to express a political message. Dreph, an artist hailing from East London, paints enlarged portraits of significant or up-and-coming black contemporary figures, and uses social media, especially instagram, to make his work known outside of the places he paints (and has gained a rather large following, as well as a commission from the black arts festival, AfroPunk). Stik, another London artist based out of Hackney, also ties in pseudo-political themes in his work: “the figures that I draw are representing marginalised communities,”5.

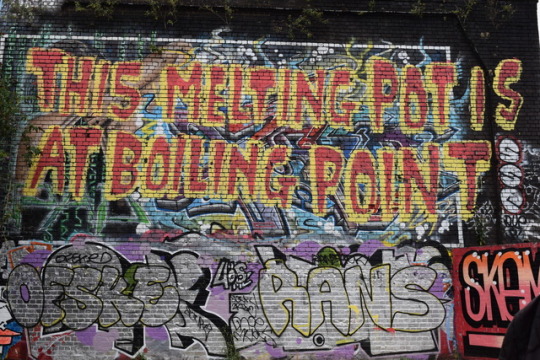

Really, the divide between that which is purely pretty and starkly, somewhat consciously offending is steep, and all the more present due to the increased hype (and ensuing pressure) in and around the landscape of Brick Lane. In Star Yard, for example, satiric caricatures of Donald Trump, posters with the words “HOMO RIOT” and a pornographic scene overlaid with imagery of iconic graffiti artists can be found adjacent, if not on top of, sunset-coloured faces, stickers of traditional-style tattoo roses, and simple displays of incredible artistry. It’s a clash of old and new school, in an environment flourishing with the movement, yet facing its potential extinction.

Gentrification is a more threatening issue for Tower Hamlets, Brick Lane, and doubtlessly other areas where graffiti and street art make up the urban landscape. The growth of financially endowed districts, socioeconomic groups, and chains directly impacts how street art and graffiti are interpreted, as an aspect of the community. As street art is commodified to fit the needs of the incoming groups and conform to a middle class ideal, its role as a subversive form of political and creative expression is changed to one of decoration, less of a statement, and more of a “statement”—less a community, more for the consumption of society, under the surveillance and capitalisation of systems that seek to remove the art form (and its participants) from its original surroundings entirely. Not everything fits into that system, perfectly. Although street art can somewhat easily be commodified and repurposed, graffiti, which is not meant to have a clear, singular, or universally understood message, is harder to take in, especially when the movement itself is meant to defy authority and express the frustrations of the artist in a system that so influences their place.

Where Stik is commissioned time and time again to retouch a piece on Princelet Street, “SONY” is quickly tagged in a metallic aerosol paint, alongside “joon” “krass”, and others, not as disrespect to the artist, but instead as an indirect affront to the sensationalist culture that, although is meant in earnest appreciation, inherently contributes to the threat against street art on the whole. It’s an insidious battleground, between the more powerful businesses that seek to gentrify and “clean up” the history of the area, slowly making it more difficult for less privileged groups to remain, and the prevailing artists that refuse to relinquish their canvas and community.

References

Akbar, A. (2008, July 15). Graffiti: Street art – or crime? The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/graffiti-street-art-ndash-or-crime-868736.html

Aulette, J. R., & Wittner, J. G. (2015). 1. Introduction, 3. Socialization and the Social Construct of Gender, 6. Work, 11. Popular culture, media, and the spectacle of sports. In Gendered worlds. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bell, B. (2016, December 16). Street Art: Crime, Grime or Sublime? Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-38316852

Jeavons, J. (2017, July 12). Excerpts from Graffiti tour (Alternative Tours London) - Brick Lane [Personal interview]

Lynskey, D. (2015, August 11) “Street Artist Stik: I felt invisible it was my way of showing I’m here” https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/aug/11/street-artist-stik-interview

Maric, B. (2014, September 25). History of Street Art in The UK. Retrieved from http://www.widewalls.ch/history-of-street-art-in-the-uk/history-in-the-making/

Merrill, S. (2015). Keeping It Real? Subcultural Graffiti, Street Art, Heritage and Authenticity. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21(4), 369-389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.934902

Oakley, M. (2013, July 15). The History of London's East End. Retrieved from http://www.eastlondonhistory.co.uk/

Porter, T. (2010, December). A call to men. Lecture presented at TEDWomen 2010, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/tony_porter_a_call_to_men

Criminal Damage Act 1971, c-48 s. 1 Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/48

#Street Art#Graffiti#East London#gentrification#brick lane#HUM4938#media analysis paper#USF#university of south florida#academic material#essay#excursions#projects

0 notes

Audio

0 notes

Audio

0 notes

Photo

Graffiti on Brick Lane | HUM4938 | Excursions

The development of Art into popular market has historically, almost always encountered a delay of interest. There are mini paradigms, so to say, of what is considered aesthetically acceptable, let alone politically acceptable to portray, which is why many of the famous artists after the classical period, members of movements that seemed to be underground and under published, received far more posthumous acclaim than when they were living—Van Gogh is a prime example, as is Vermeer, Monet, Cezanne, Manet, and countless others. Recently, the half lives of pop culture seems to have become less and less lengthy, in the interest of entertaining new art forms, and perhaps too, in the interest of catching up to the forefront of artistic movements, something that is now possible in a digital age.

For a quick intro to the area, catch up in this montage of Brick Lane.

youtube

As of the twentieth century, that chase for a pop culture has followed in the wake of African American artists, at least in the states. From the rise of vaudeville, to jazz, to rhythm and blues, rock, funk, disco, soul revival, to hip hop, to rap, the music of black artists has been largely appropriated and unjustly reclaimed by more ‘marketable’ (pronounced: white) figures. Thankfully, at the start of the second millennia, more credit has been duly given to black culture for music, especially. Most of these genres arose out of a need for expression. Jazz and blues originated in the disadvantaged communities of the generations after those displaced by slavery, not in a direct response to the government that restricted their rights, but instead as a means of expression, of community, of solidarity through skilled performance, ragging and jiving and wailing about life, those issues and day to day feelings that arose—of course it included the struggle of the black individual, but that was an obvious fact. Jazz was not entertainment, or a political movement, but a medium of community.

That chase is especially relevant in the streets of East London today, where yet another marginalised form of artistic expression, graffiti writing (and the distilled street art), faces both vehement prosecution and pointed interest. The off-gassed physical expression of hip-hop culture is at the crossroads of the popular market, appreciating or appropriating the works, and a system that finds it still too revolutionary to the paradigm of acceptable aesthetic and political contemporary expression.

Although graffiti and street art have both been widely appreciated elsewhere, in the states, and even on a global scale supported to a wide degree (artists like Shepherd Ferry “OBEY”, Invader, Ronzo, Banksy, etc are internationally recognised and make quite a lot of money from the overground market), the place where individuals still seek to express their original ideas in the form of the original art is restricted. In part, because of the clash between the historically socioeconomically displaced neighbourhood there, and the growth of an illustrious business district that, understandably, seeks to expand. Not by adoption of the community, but by appropriation of the popular community inter actives and gentrification of the areas surrounding. On its side is the police and local government, which still holds graffiti artists accountable for up to £2,500 or 10 years in prison (if above the age of majority) or two years for minors age 12 to 17, under section one of the criminal act of 1971, regarding criminal damage and prosecution. That being said, not all sites are illegal to tag (Star Yard is one of those grey-areas, an open gallery)—but with increased security brought on by the financial district, and more pressure, financially, for surveillance to take place, the original significance of graffiti, to tag and write where the artist wanted as a means of communication with other artists, becomes harder to do.

That is, unless you’re commissioned or sanctioned to paint a piece—which changes your status from public enemy, to public servant. Larger pieces seen down fashion street or in Eli’s yard, painted or installed by more mainstream or popular artists. A local artist might too be asked to paint a local business’ building, but when this art piece becomes a permanent installation, the form of art changes, from Graffiti, and street art, to something else.

This implies a kind of sanctity to street art that isn’t necessarily a part of the original intent of the form. Graffiti and street art are recyclable—they’re a form of communication, after all. When someone tags, it stays until someone else can cover it with theirs, in a more elaborate way (as to show respect—a simple tag or stencil that interrupts the piece might not be the best idea)—it evolves. When a piece is worn down, another artist can build on top of it. But the newfound culture of appreciation of graffiti, of interpretation and projection of meanings that might not necessarily have been intended, is a part of the popular art culture (of museum art culture) that simply seems alien to street artists. Upon encountering a piece by artist Stik, who is of some relative popularity, we were told that he’s on occasion asked to return to the particular piece to touch it up and restore it—something that is never really thought to happen. In protest, a few other artists have tagged over it—not in disrespect to Stik, so to say, but to those that keep the art up when it’s meant to expire—the tourists that apply themselves to the culture of capitalisation and gentrification that is threatening the art form in its place. Want more information on East London? Check the media analysis paper here

Sources and further reading:

The Criminal Act of 1971

Stik 2016 interview

Merrill, S. (2015). Keeping It Real? Subcultural Graffiti, Street Art, Heritage and Authenticity. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21(4), 369-389.

Maric, B. (2014, September 25). History of Street Art in The UK.

Bell, B. (2016, December 16). Street Art: Crime, Grime or Sublime?

2 notes

·

View notes