#HOW IS A MOTH FLYING EXACTLY LIKE A HUMMINGBIRD

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Everyone please go google hummingbird moths right now. Unreal thing i saw today. Pls pls pls you won't regret it trust me.

#HOW IS A MOTH FLYING EXACTLY LIKE A HUMMINGBIRD#it puzzles me so much it loojs exactly like a hummingbird moth hybrid like HOW DO YOU EXIST.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So um I was gonna make a faesona for the @valrayne-faeu AU

But I got distracted part way through and turned it into the older tree sibling OC I made from this one fic

Prinxe is the gender neutral word for prince/princess since they are non binary :3

Also their wings are from a clearwing moth (they fly like hummingbirds!!) and they were born long before the twins

Anyway, I'm gonna ramble about their backstory under the cut

So technically speaking, they were in line for the throne, but since they are presumed dead, they aren't exactly going to get it

Nor do they want to

I'm not sure how Nim is in this AU (since we didn't get much about her) but I will say that whether it was to be controlling, or simply because she genuinely thought it was best, she put a lot of pressure on them

And eventually, they couldn't take it anymore and left

However, the timing of their departure alined with an assassination attempt from a very bold mortal

So Nim thought they died and I'm going to pretend this was the reason she turned herself into a tree and made the twins

And then when they heard about the assassination attempt a while later, they thought that was how Nim died and figured the courtiers would be going for the throne and just decided not to get involved

They took their time to grieve and then just tried to figure themself out

I've decided they traded their gender to some random trans mortal in exchange for their deadname since it was the one being used at the time

Most mortals leave them be because tree monsters have always had a stronger connection to fae than other monsters so them acting a little weird is actually normal lol

Their wings are transparent enough that they aren't noticed from a distance unless they spread them open

Also, I might make it that all the tree monsters came from tree sibling by accident lol

Idk, still deciding on that

#midnight attempts art#undertale#undertale aus#fae au#valrayne faeu#faeu oc#original character#oc#sycamore#tree sibling

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hundred Demons

notes: i accidentally deleted my other naraku fic so have some uhhh questionable romantic liaisons rating: teen, there’s some making out but nothing heavier pairing: naraku / reader word count: 1,796

You pry up the cellar door and flinch at the smell of decay. The castle festers at its core, exacerbated by Naraku’s transformation.

He detests this state, but the struggle of holding his body together is prolonged by denying it. His most precious asset is his ability to reforge flesh, And for this process he prefers to be alone. You know that. Still, you descend.

The smell is worse with your feet in the dirt. You’re careful not to grip the ladder too tightly, should your grip make the brittle wood crumble. You closed the hatch before climbing down, the only light now from the cracks around its edges.

It’s barely enough to make out the mass in the centre of the room, but your eyes adjust. A wriggling, pulsing thing blinks it’s single eye. Then, another tendril uncoils slowly, as if in sleep. Knotted together and writhing as one are a hundred demons.

At their centre is his head, bowed in sleep.

You feel a lurching sensation, a knee jerk reaction to the dirt in the cellar. It feels like old, dried blood beneath your feet. The corruption has seeped into the support beams of the cellar. You doubt the place would stand on its own if not for his magic.

Blinking slowly, you wait for the head to notice you. A demon’s maw lolls open, it’s fleshy tongue poking out at you before it also succumbs to sleep. Naraku’s body twitches unnaturally, and then his true head finally moves.

You see two red eyes beneath his black fringe. His skin is so pale, white in the shadows like a death mask. He sneers in your direction, seeing nothing but darkness and the faint outline of a person.

“Kagura?” he snarls. His eyesight is poor when he���s in pieces. Naraku inhales sharply, recognizing the new blood that woke him is human.

“No,” you reply, “it’s me.”

“Hm,” he grunts. It’s difficult to tell if he’s still angry. “I did not summon you.”

You shift your weight to your hip, hazarding to step closer. No doubt he’s irked at his sleep being interrupted, but you understand that his desires are always a double-edged sword. Regardless of your actions, it’s his natural state to be displeased.

“I missed you,” is the only excuse you can offer.

You half expect him to dismiss it as pathetic, but instead Naraku hides his shock beneath a grimace.

“I didn’t think you were foolish enough to disturb me as I regenerate,” he finally tries, though it lacks the bite you know he can have.

“I didn’t mean to disturb you,” your chin is still raised to look at him. But Naraku understands that it is at once both practical and an act of defiance. Despite that, he can’t bring himself to lash out.

Instead, he laughs. It’s like dark water, pulling you in a few more steps. You’re lulled into a half-way sense of safety, worried less for your own bodily health. Perhaps it’s too soon, you fear. But Naraku seems unwilling to pin you with cruelty.

“Of course, I suppose I am the one who disturbs,” he says, “at least, for the time being.”

His cheeks are gaunt and heavy bags hang under his eyes. He looks tired, his voice is barely more than a reedy breeze. He creaks more than he speaks. You move even closer, until your toes touch the edge of the mountain of demons.

Naraku’s head is supported by a nexus of thick, gray tubes. His hair is entwined with the cellar rafters. He is hideous, you can admit that, and yet you shake your head.

“Do I not terrify you?” he asks, sounding more amused than shocked or angered by your lack of reaction. He does so love fear. “Most can’t bear to look.”

“Have many people seen you like this?” you ask, cocking your head to the side. You kneel on the body of the demon at your feet, using it as a stepping stone to get to the second.

Naraku makes a dismissive noise, unwilling to grace your question with an answer. He lacks one that will prove his point, and that annoys him.

“I thought as much,” you reply, “Kagura’s opinion hardly counts, in that case.” The demons are foul to the touch, but you manage to climb them one by one. Naraku stays terribly still as you do so, waiting and watching to see what you’ll do.

“And yours does?” he asks. A hint of thank ink-black, cruel humour creeps into his voice again. Still, you don’t flinch. He wonders if you might wish to hear him laugh again.

“Generally yes,” you kneel on the back of a sturdier demon, your eyes at level with his. “As I’m your lover,” you’re close enough for him to smell your blood, and the hummingbird beat of your heart.

You’re fragile, he thinks. But then again, so is he. And you’re looking at him with the worst kind of adoration a creature like him can fathom. Still, in his chest that’s now in pieces on the cellar floor, his heart that was once human lurches in your direction.

“You make a compelling argument,” Naraku decides. There is still a sharpness in his eyes, and it comes from ugly fear. You’re close enough that in a single, violent motion he could be dead. And your knife could be bloody.

But you keep your hands on your knees, looking at him with your head tilted. You move slowly, as if you know exactly what he’s afraid of. Maybe he has a right to be unnerved by this, but that won’t make you stop.

You lift your hands and put them on his cheeks, wiping dirt and grime from his face. His thin lips turn up into a smirk. He is a monster, a hateful, terrifying beast of hell and still you lean in to kiss him.

Your lips are human and soft. You’re warmed through, not disquietingly clammy the way he is. But you seem not to notice. You seem to reach through the haze of evil energy and the smell of decay to find the spark of heat belonging to Onigumo. That bit of life that makes you love him so.

He drags his tongue across your bottom lip, demanding out of habit that he be granted entry. Naraku gets what he wants, he’s used to that. So when you press your mouth closed, making a tight seal that his sharp teeth can’t break-- his eyes open.

“Did you come here only to torment me?” he asks, pulling away enough to be coherent. But he’s still so close.

He’s never felt more like an insect than when chasing your warmth. Naraku has looked on at moths flying headlong to their death, toward fire and now he understands why. It’s addictive, your humanity. It’s like a song that he could fall into.

He wishes he had arms, that’s what the longing in his displaced chest is telling him. He’ll wrap you up and keep you with him for hours when he’s finished remaking his body. And you won’t be able to deny him a thing.

But for now, you look at him with an amused expression he does not appreciate. You have ideas above your station and too little fear for his taste. At least, until you press your lips to his again.

It seems you grant him permission to deepen the kiss now, though he doesn’t know what’s changed. He’s the same as he was a minute ago, just as breathless and horrible to behold. Perhaps you simply wanted to prove you could control him.

That thought is simultaneously gut-wrenching and delicious. Naraku doesn’t know which is worse.

The smell of rot doesn’t register as pervasively, you notice. You put your hands in his long, black hair and drag his severed head against your mouth. Your fingers brush gray-mottled tendons and pale flesh.

He’s making decisions about which parts of him to keep even as he accepts your kiss, but he’s working a lot slower than before you arrived.

You have a nice time ruining his solitary confinement, sneaking kisses over his cold flesh. You try your best to warm him, he realizes, and the sentiment is unhelpfully pleasant. He loses count of how many times he needs to reconsider his decision to discard part of himself, you’re a beautiful distraction.

“I’m inhibiting you,” you say when you finally pause to breathe. He mirrors the action, struck very suddenly by how distant the need to do so was with your mouth to his jaw.

“Deeply,” he replies.

“My apologies,” you say, bowing your head. “I really did miss you.”

“If it would please you,” he begins, making you lift your head, “you may stay a while longer.”

“It would please me,” you reply. You kiss the corner of his mouth, moving too quickly for his poor vision to see. “I’ll be still as a mouse so you can be done sooner.”

Naraku closes his eyes, taking a deep breath before nodding. You can feel a shift in the cellar as he goes back to sleep. So much for parting remarks, you suppose. But he isn’t one for affection, especially not when vulnerable.

You sit back on your knees, watching his severed head hang from the rafters. And the sight, to your intense displeasure, inspires no fear. You know what he is, who he is, and still you make yourself comfortable.

Somewhere in the space between Naraku regrowing his neck and shoulders, you too succumb to sleep. The dark, cool cellar fades away, as does the smell of rot. You lean against the old wooden wall, the demons underfoot don’t bother you.

By nightfall, he’s finished. And you, his lover, lie curled up on the packed earth. His body is as it was, but now it’s much stronger. He feels better, more in control and sturdy. As much as he would like to look down on you with vague disgust brewing in his now rightly-placed heart, he can’t.

You’re roused hours later, somewhere just as dark but less oppressively macabre. You’re not in the cellar any more, you know by the smell. The wet, old air is cleaner in this new place.

Your fingers brush the floor, no longer made of packed earth. It’s tatami, you realize, the same tatami found in Naraku’s private chamber.

Sitting up, you realize how warm you are in this new place. Even in the blue-dark, you can’t feel anyone else’s eyes on you. You’re alone.

You look down next, wondering what’s covering you. You didn’t bring anything when you climbed down the ladder. But thrown over your chest, undisturbed by your heavy sleep is a white cloak of baboon fur.

#naraku#naraku x reader#inuyasha#inuyasha fic#anniewrites#this gets Bad near the end i'm sorry#i ran out of wenergy

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vertebrate Wings, PART 3: Flight

Return to main post + TOC >>HERE<<

Flight TOC

Basic Flight Theory

Bird vs. Bat vs. Pterosaur

Aspect Ratio and Wing Loading

Special Cases: Hoverers

Basic Flight Theory

I will openly admit here and now, I’m not well-versed in physics. I apologize if this section is a bit disorganized, since I’ll be stitching together others’ more comprehensible flight descriptions/explanations.

This first bit is from a kind follower, Rahjital, who sent us this quick explanation of flight theory a while back (sadly the images they added no longer seem to be working, so I tried to find fitting images as substitutes):

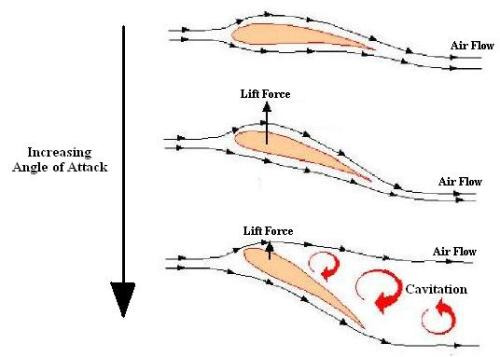

The first step to learn how lift works is to debunk the popular explanation of how lift forces are created, called the Equal Transit Time theory. The reasoning is that air flowing around the wing splits into two streams, one of which has to travel over the wing and another which travels below it. Due to the shape of the wing, the upper stream has to move faster to cover the same distance. This difference in velocities generates a difference in pressure and therefore lift.

However, what happens if you fly upside down?

The upper side of your wing points towards the ground, and so does the lift force. I would have said you’d fall like a rock, but the fall would actually be faster since your wings would drag you down. We all know that’s not how flight works, though, so how is lift actually created?

All you need to do is tilt the wings a bit. Seriously, I’m not kidding. No need for a specialized wing shape, as the majority of people seems to believe. (although it helps.) Why? Let me explain:

There are two phenomena causing lift to be created:

1. As air flows around the wing, its direction changes downwards and it leaves the back edge of the wing moving slightly more down. Mister Newton tells us that every action has its reaction, so if the air moves down, our wing has to rise.

2. Due to the tilting, the air flowing on the underside of the wing ends up colliding with it and slowing down, raising the pressure. On the other hand, the air flowing over the wings goes upwards because it has to get over the raised front edge, but as it can��t get back down immediately, it ends up travelling in an arc over the wing. This forms a small ‘pocket’ of low pressure straight above the top surface of the wings. These two fields of pressure then generate additional lift. (this is similar to how the Equal Transit Time theory states lift is generated, but with a very different reason, and not as important as the theory states it to be).

Next time you are traveling in a car, try reaching out of the window with your arm when going reasonably fast. As long as you keep your hand parallel to the ground, not much is going to happen, but once you tilt it even a little, the wind is going to push it up. (or down, depending on which direction you tilted it.) That’s it - your hand is generating enough lift to hit the frame of the car window. Just imagine how much lift does a properly built wing get in a similar situation.

The tilt I am talking about the entire time here is called the angle of attack, often abbreviated just AOA. The greater the angle of attack is, the more lift is generated, but the more drag there is, too. For airplanes, the AOA is negligible from an artist’s perspective, but for winged creatures, this is far more of a concern.

Therefore, the flight theory rule #1 is: Whenever you draw a flying creature, always make its wings slightly inclined. It wouldn’t be able to fly otherwise.

~~end quote~~

Bird vs. Bat vs. Pterosaur

This first bit will be borrowed from Koryos’ article “Bat Flight Versus Bird Flight” (which I highly suggest reading in-full for a deeper explanation). Fair warning though—from the short explanation they give of basic flight/lift, it seems they do believe (at least at the time of writing the article) in the now-defunct Equal Transit Time Theory, though their points on bird vs. bat flight are still valid otherwise:

If you look closely at the above gif, you’ll notice that at several points during flight, the bat actually bends its fingers, which dramatically changes the shape of its wings. Birds do not have joints in their feathers, so they cannot do this.

....

Flexible joints are not all the bat has in its arsenal. Its actual bones are flexible, due to a lack of calcium in its diet. This means that they deform and reform their shape during flight.

Birds minimize air resistance by rotating their primaries during their upstroke, allowing air to slip between the feathers. Bats, with solid membranes, can’t do this- so they have an even finer means of control. There are lines of muscle present within the bat’s wing membrane that can actually change the stiffness and malleability of its skin. You can see them quite clearly under the skin of our entangled bat friend.

This is a big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), by the way.

These muscles allow the bat to make their membranes flexible during their upstroke to decrease resistance, yet stiff during their downstroke in order to provide lift. It also allows them to change the camber (angle) of their wings on a whim!

This slow-mo video really displays just how incredibly flexible bat wings are.

youtube

Bat wings are also covered by millions of tiny, hyper-sensitive hairs that allow the bat to sense air currents and adjust accordingly.

So what does all this control do for the bat?

Well, for one thing, it means they’re not limited by symmetry. Bird wings will almost always mirror each other in shape, while bats may form two different wings shapes at the same time, allowing them to perform some crazy aerial acrobatics. Some insect-eating bats will actually grab an insect by wrapping one wing around it midflight (don’t believe me? You can see it in the beginning of this video!) and then get the insect in their mouth all in a split second, while still flying.

Now, in terms of speed, birds can generally outpace bats. But in terms of maneuverability, bats can fly circles around birds.

The fact that bats’ bones, unlike those of birds, aren’t hollow, and that their skin is heavier than feathers might seem like a disadvantage- but it isn’t. Birds have much more mass in the center of their body than they do in their wings; by contrast, bats have more mass distributed through each wing (12-20% per wing). This means that bats can actually push off their own mass to do things like flip, spin, roll, etc. No bird can stop midflight and flip over to land upside-down, but bats can.

Because they have such fine control over their airfoil shape, bats can also generate lift using less energy than birds. Remember when I talked about minimizing surface area during the upstroke and maximizing it during the downstroke? Bats can bend their fingers and ‘crumple’ their wings as they raise them, conserving energy. Think of it like opening and closing an umbrella. While birds can pull their feathers together more tightly, they can’t exactly clench them like fists.

Decreasing energy costs is good in any situation, but particularly for fliers. It takes a lot of energy to fly. In this case, bats can outcompete both birds and insects for energy efficiency- one study found that nectar-feeding bats, though the largest in size, expended the least energy hovering when compared to both moths and hummingbirds.

~~end quote~~

As for pterosaurs, I’ll leave it up to Mike Habib’s article “Feathers vs Membranes”:

The structure and efficiency of pterosaur wings is obviously not known in as much detail as those of birds or bats, for the simple reason that no living representatives of pterosaurs are available for study. However, soft tissue preservation in pterosaurs does give some critical information about their wing morphology, and the overall shape and structure of the wing can be used (along with first principles from aerodynamics) to estimate efficiency and performance.

…((I’ll just be pasting the basic findings, but please read the full article if you’re interested in specifics))…

Now, for some punchlines...

Based on the structural information above, we might expect the following regarding pterosaurs and birds:

- Pterosaurs would have a base advantage in terms of maneuverability and slow flight competency.

- Pterosaurs would also have had an advantage in terms of soaring capability and efficiency

- Pterosaurs would have been better suited to the evolution of large sizes (though this was affected more by differences in takeoff - see earlier posts about pterosaur launch).

- Birds will perform a bit better as mid-sized, broad-winged morphs (because they can use slotted wing tips and span reduction).

- Birds would have an advantage in steep climb-out after takeoff at small body sizes (because they can work with shorter wings and engage them earlier). This might pre-dispose them to burst launch morphologies/ecologies.

~~end quote~~

(other articles by Habib about Pterosaur anatomy and flight can be found here and here, for anyone interested)

When Exdraghunt linked us this information about pterosaur wings, it was in relation to a question about pterosaur keels and why they differed from bird keels. Exdraghunt suggested this might be due to pterosaur preference for soaring compared to bird flapping. However, plenty of inland pterosaurs could have been flappers, so I think the shallowness is more likely caused by their muscular setup compared to birds, discussed in more detail in the Basic Anatomy section.

Aspect Ratio and Wing Loading

Now that we have a basic understanding of the different modes of vertebrate flight, we can get to the fun stuff—wing diversity! Believe it or not, my friends, wing shapes and sizes can drastically effect an animal’s flight style.

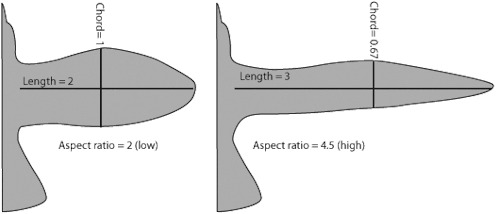

Aspect ratio is the ratio of length to width in a wing, where high ratio indicates narrow wings, and low ratio indicates wide wings.

Loading is the ratio of body weight to wing size, where low loading = large wings + small weight, and high loading = small wings + large weight.

Measuring these two aspects against each other helps us determine different flight styles.

For a short n’ sweet rundown:

1) Long, narrow wings (low loading, high ratio)= gliding, low speed

2) Long, wide wings (low loading, low ratio)= soaring

3) Short, wide wings (high loading, low ratio)= high acceleration (burst speed), maneuverability

4) Short, narrow wings (high loading, high ratio)= high speed

Though there are other aspects of wing shape to take into account as well.

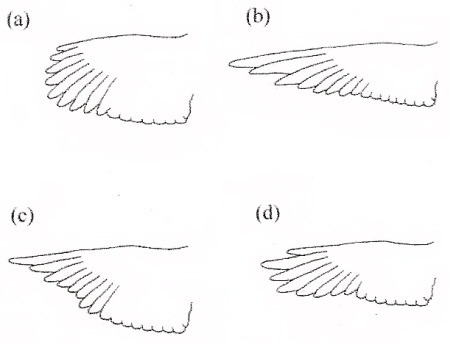

(via^)

Pointedness refers to a wing tip’s position on the leading edge; IE- is the longest point of the wing further back behind the leading edge (A, round), or does the longest point lie along the leading edge (B, pointed)?. Rounder wings increase thrust, and lend towards greater maneuverability-- particularly in short/wide wings. Pointed wings reduce drag on the air (which increases speed), particularly in short wings, and can make for smoother flight.

Convexity refers to the acuteness of a wingtip; IE- is the shape of the wingtip curved relatively inwards (C, concave) or outwards (D, convex)? Concave wings are better suited for constant high speed. Convex wings create more lift, so are ideal for slow flying and increase acceleration.

Measuring these two aspects against each other gives us another fun chart of wing types.

(via^)

And let’s not forget that slotted wings—those whose primary remiges have notches which create gaps between these feathers—reduce drag and tend to be found in wide (low ratio) wings.

Put all these aspects and little details together, and you can observe some very unique flight patterns. Most ornithologists tend to organize wings into 4 different types, as shown below.

Though I personally like to use a few more types as organization (list via):

1) Marine soarers are birds that fly for long periods over the open ocean and have very high aspect-ratio wings and average or low wing loading that reduce the energetic cost of flight. Birds in this category include the albatrosses (Procellariiformes).

2) Divers/swimmers are birds with medium to high aspect ratios and high wing loading, including murres, loons, grebes, scoters, mergansers, ducks, and swans. These birds fly rapidly, but with limited maneuverability, characteristics useful for birds that often fly long distances (e.g., during migration or to feeding areas) and take-off and land on water where precise maneuverability is not as important.

3) Aerial hunters are birds with high aspect-ratio wings and low wing loading, a combination permitting rapid flight and excellent maneuverability. Aerial hunters include swallows and martins (Passeriformes), swifts (Apodiformes), nightjars (Caprimulgiformes), Swallow-tailed Kites (Falconiformes), frigatebirds (Fregatidae), terns (Sterninae), some falcons (e.g., hobbies and Eleonora’s Falcon), and tropicbirds (Phaethontidae).

4) Soarers/coursers include birds with low aspect ratios and low wing loading, characteristics that allow relatively large birds to either soar or fly just above the vegetation in open habitats in search of prey. Birds in the soaring category include hawks and eagles (Falconiformes), vultures, condors, and storks (Ciconiiformes), and cranes (Gruiformes). Coursing birds include some owls (e.g., Barn Owl and Short-eared Owl; Strigiformes) and harriers (Falconiformes).

5) Short-burst fliers are birds with low aspect ratios and high wing loading that fly infrequently and only for short distances. Birds in this category include those in the orders Galliformes (e.g., turkeys, pheasants, quail, grouse, and megapodes) and Tinamiformes (tinamous).

6) Hoverers are birds capable of flying in one position without wind and have high aspect ratios and, surprisingly, high wing loading. The high aspect ratio reduces the energetic cost of flight, whereas the high wing loading permits relatively fast, agile flight (Rayner 1998). The only true hoverers are the hummingbirds (Apodiformes).

~~end quote~~

I don’t have an outside source to verify this observation, but I’ve found that a longer ���hand” section and shorter arm generally correlate with high-speed flight, while a shorter “hand” and longer arm correlates to low-speed gliding. I can only assume this may be due to a shorter arm section being easier to flap rapidly, but again, this is conjecture.

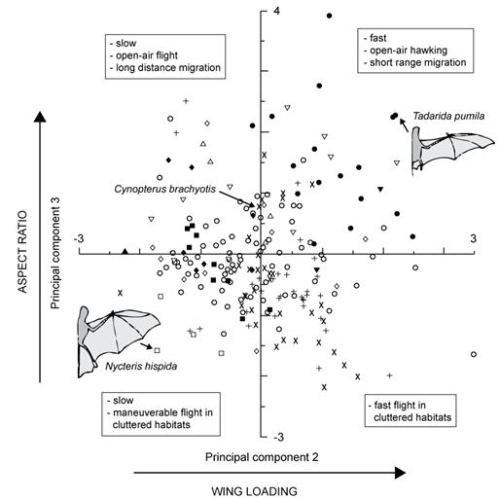

While much of this information is bird-specific, I was able to scrounge up a graph of bat aspect ratios and loading, so I can only assume these concepts similarly apply to bat flight.

(via^)

There sadly seems to be much less information available on bat wing/flight diversity…

As for pterosaur wing diversity, exdraghunt sent in some great input (as well as that chart of different bat wings featured above~):

There actually is a fair amount of wing diversity among pterosaurs, and it fairly closely parallels that in birds. (Though they do not reach the extreme variety in shapes that birds do, due to the limitations in variety of “arm+wing finger” combos)

One of the most extreme examples is Nyctosaurus gracilis, a long-distance marine soarer, similar to albatrosses. They have very long, thin wings (and also lost their other wing fingers, presumably because they came on land rarely)

Other species of pterosaur, like insect eaters (which need short, broad wings for manuverability) or over-land fliers would’ve had different wing shapes.

Some of this difference was achieved by varying the ratio between “arm” and “wing finger” lengths. You’ll notice that smaller, earlier “Rhamphorhynchoids” (the top half, with the long tails) tended towards short arms vs long wing fingers. While larger, later Pterodactyloid species developed longer arms in relationships to the wing finger. (Especially in the wrist)

Wing shape silhouettes, by Mark Witton. (Not to scale, obvs.)

~~end quote~~

Special Cases: Hoverers

Hoverers such as hummingbirds are special cases in the world of vertebrate flight, because much of their lifestyle and physiology mimics that of insects-- including their flight.

The basic rules of flight theory discussed above won’t exactly apply to these guys, because air doesn’t travel over their wings in the same way it does in other vertebrate flyers. Take a look at this post and compare the animations between the hummingbird, goose, and bat. What exactly is unique about the hummingbird animation compared to the other two?

A few things-- for one, hummingbirds don’t have nearly as many points of wing articulation during flight. If you look closely, you’ll see there’s no bend at the elbow or wrist for a hummingbird; they move their whole arm in a completely stiff, figure-8 pattern. Such high-speed flapping can’t handle that much articulation.

Why a figure-8? Here’s the thing-- hummingbirds don’t technically have an upstroke they have to account for. Every stroke of their wings is a downstroke because when they pull their wings back, the topside of their wings tilts down and also pushes against the air as a “downstroke”. Thus, there’s never a gap between downstrokes-- they’re always efficiently pushing down against the air.

This is also why, unlike most every other flying vertebrate, their flight is more vertical than horizontal. In order to properly swing their wings in a figure-8 motion, they have to tilt their bodies up.

While hovering flight is cool as hell, it comes with a lot of restrictions; mainly, hoverers are always small. The energetic restrictions required for hovering are so incredibly high that bodies much bigger than a hummingbird wouldn’t be able to consume enough energy to make up for hovering. Plus, hoverers tend to live right on the edge of starvation because what energy they do manage to consume is used up so quickly.

If you do want to integrate hovering into your dragons, consider making it a secondary form of flight that they can only keep up for short bursts, rather than their primary mode of flight. Unless you’re ready to give your dragon a lot of physiological restrictions, which is cool too.

-Mod Spiral

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

[Anonymous: “King, tell me a fact about hummingbirds? My curiosity has gotten the better of me. Besides, who doesn't enjoy the colors they bring? - Stal”]

“Because of this question, I had to spend some time thinking about what *not* to mention about hummingbirds. These small birds have the most wonderful and fascinating adaptations for their flight patterns.

Even something as small as the way their muscles form and move in flight…. Its a stroke of genius. Using particle image velocimetry techniques in photography, we can see how they actually *generate* the lift needed to hover. What’s very interesting about this is that they do it nearly entirely backwards from any other avian species. In terms of how it works, they use the downstroke of their wings to produce a full ¾ of their weight support in the air, leaving only a quarter to the upstroke. Doing this, their wings produce a “figure 8” motion, keeping them hovered in the air.

And with that in mind, birds dont really.. “Do” that. It’s such a strange thing that it used to be assumed that hummingbirds had a *very* equal weight support. As in, both an upstroke and downstroke wing beat would support the same amount of weight up and down in the air. Many studies assumed that, simply because its exactly how many insects do it. Simply put, its untrue. Hummingbirds have formed their entire base flight structure similarly to something like a Hawk Moth. They are incredibly unique this way, making all of my work…. interesting.

Understandably, this has the result of a *very* new muscle structure within hummingbirds that other avians dont share. Sustained flight in avian species is produced through two major muscle groups, the Pectoralis Major, and Supracoracoideus. Essentially, these two muscles allow birds to spend the majority of their energy on the downstroke and upstroke mechanisms of the wing. In Hummingbirds, the strain they put on their pectoralis major is in fact the *lowest* recorded in *any* flying bird. This is interesting due to how much of their weight is supported by the downstroke, dictated by this muscle entirely, as mentioned earlier. Meaning the upstroke, which supports very little of their weight, holds strain at a proportionally larger amount than any other bird species…. thats so fucked up.

These adaptations to keep hovering in the air for as long as Hummingbirds do means they have an incredibly unique adaptation- no alula. The Alula is the small grouping of feathers along the anterior edge of a flighted bird’s wing. It functions a lot like a “thumb” in the way that it sits in terms of bone structure, and thats how a shifter like me would have to think about it to form one correctly. In other birds capable of flight, the Alula functions like that of the slats in the wings of an aircraft carrier, to control speed. Alulas can be manipulated in the same way, to assist in a softer landing. Hummingbirds simply…. Dont have one! The digit is there, but the function is entirely vestigial. A hummingbirds sesamoid bones are essentially fused where they need to be, and they dont use any extra help with landing since they are in full control of the speed they keep in the air. I still keep it, however, for measurement purposes. With an alula, I can keep track of where to place the boundary between primary and marginal coverts.

In terms of how all of this works out in the end, the end result is a bird that weighs 0.16 oz and can beat their wings 80 times per minute, achieving a hovering flight modern day innovations in the helicopter industry can only dream of achieving. Research into how the best hummingbirds fly versus the world’s most advanced micro helicopters suggests they are capable of being up to 20% more efficient in terms of the power needed for lift. These small birds have perfected the art of natural, sustainable hovering that humans struggle to dream of, and I can only hope to even *look* like one someday. I’ll be honest, flight is not exactly my main concern in this work, but if I can stumble upon it in the process, it will be a dream come true.

Fuck, I almost forgot what I was actually going to say as the fun fact. To begin explaining, and it *does* take some explaining, Hummingbirds have adapted extremely well to barometric changes and major altitude changes. Different species living in vastly different environments adapt for life using more power per wing beat by changing the size of their wings. Higher altitude means larger wings, which means fewer issues when lifting themselves into the air at lower air densities. Smaller wings, of course, for a similar effect in higher air densities. Essentially, hummingbirds want to eliminate any and all wind resistance at the *exact right amount* to keep themselves steady…. For nectar. What a wonderful way to live.

Understandably, that leads us to the cutest thing I have yet learned about Hummingbirds. They…. Get this…. Shake like dogs in the air during flight in the rain. Isnt that adorable???? They have to shed water to avoid gaining too much weight in water drops so they can continue sipping nectar comfortably!!!! When the water droplets collect, they can weigh the bird down enough that they must change their posture. They do this by starting to fly fully horizontally, beginning around 38% (38%!!!! Over a third of their body weight in little drops of water sitting on their back!!!!) of their weight. They also have to beat their wings faster (yes, faster than *80 beats per minute….*), and reduce the angle of motion in heavier rain to avoid the extra strain on their muscles! It’s a wonderful thing to see in action, and I suggest finding videos that show you accurately what this looks like.

Look, I just really like dogs. And Im finding Im starting to like birds just as much. Theres *so* much to them. There’s other things I didnt mention, like how most birds knees are internal, or that the alula is also known as the bastard wing. But from having to use massively technical photography methods to capture very small motions that any other flight bird would be genuinely incapable of, to using their muscles more like insects than their avian family, hummingbirds are just…. Absolutely stunning. Its a wonder, really, how someone like me could ever come this close to being as beautiful :)”

Tags: “#:) they make me happy #and she seems to like them”

ꖌ╎リ⊣, ℸ ̣ ᒷꖎꖎ ᒲᒷ ᔑ ⎓ᔑᓵℸ ̣ ᔑʖ𝙹⚍ℸ ̣ ⍑⚍ᒲᒲ╎リ⊣ʖ╎∷↸ᓭ? ᒲ|| ᓵ⚍∷╎𝙹ᓭ╎ℸ ̣ || ⍑ᔑᓭ ⊣𝙹ℸ ̣ ℸ ̣ ᒷリ ℸ ̣ ⍑ᒷ ʖᒷℸ ̣ ℸ ̣ ᒷ∷ 𝙹⎓ ᒲᒷ. ʖᒷᓭ╎↸ᒷᓭ, ∴⍑𝙹 ↸𝙹ᒷᓭリ'ℸ ̣ ᒷリ⋮𝙹|| ℸ ̣ ⍑ᒷ ᓵ𝙹ꖎ𝙹∷ᓭ ℸ ̣ ⍑ᒷ|| ʖ∷╎リ⊣?

- ᓭℸ ̣ ᔑꖎ

⏚⟒☊⏃⎍⌇⟒ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⍾⎍⟒⌇⏁⟟⍜⋏, ⟟ ⊑⏃⎅ ⏁⍜ ⌇⌿⟒⋏⎅ ⌇⍜⋔⟒ ⏁⟟⋔⟒ ⏁⊑⟟⋏☍⟟⋏☌ ⏃⏚⍜⎍⏁ ⍙⊑⏃⏁ *⋏⍜⏁* ⏁⍜ ⋔⟒⋏⏁⟟⍜⋏ ⏃⏚⍜⎍⏁ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇. ⏁⊑⟒⌇⟒ ⌇⋔⏃⌰⌰ ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⏁⊑⟒ ⋔⍜⌇⏁ ⍙⍜⋏⎅⟒⍀⎎⎍⌰ ⏃⋏⎅ ⎎⏃⌇☊⟟⋏⏃⏁⟟⋏☌ ⏃⎅⏃⌿⏁⏃⏁⟟⍜⋏⌇ ⎎⍜⍀ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⌿⏃⏁⏁⟒⍀⋏⌇.

⟒⎐⟒⋏ ⌇⍜⋔⟒⏁⊑⟟⋏☌ ⏃⌇ ⌇⋔⏃⌰⌰ ⏃⌇ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍙⏃⊬ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒⌇ ⎎⍜⍀⋔ ⏃⋏⎅ ⋔⍜⎐⟒ ⟟⋏ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁…. ⟟⏁⌇ ⏃ ⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒ ⍜⎎ ☌⟒⋏⟟⎍⌇. ⎍⌇⟟⋏☌ ⌿⏃⍀⏁⟟☊⌰⟒ ⟟⋔⏃☌⟒ ⎐⟒⌰⍜☊⟟⋔⟒⏁⍀⊬ ⏁⟒☊⊑⋏⟟⍾⎍⟒⌇ ⟟⋏ ⌿⊑⍜⏁⍜☌⍀⏃⌿⊑⊬, ⍙⟒ ☊⏃⋏ ⌇⟒⟒ ⊑⍜⍙ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⏃☊⏁⎍⏃⌰⌰⊬ *☌⟒⋏⟒⍀⏃⏁⟒* ⏁⊑⟒ ⌰⟟⎎⏁ ⋏⟒⟒⎅⟒⎅ ⏁⍜ ⊑⍜⎐⟒⍀. ⍙⊑⏃⏁’⌇ ⎐⟒⍀⊬ ⟟⋏⏁⟒⍀⟒⌇⏁⟟⋏☌ ⏃⏚⍜⎍⏁ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⟟⌇ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⎅⍜ ⟟⏁ ⋏⟒⏃⍀⌰⊬ ⟒⋏⏁⟟⍀⟒⌰⊬ ⏚⏃☊☍⍙⏃⍀⎅⌇ ⎎⍀⍜⋔ ⏃⋏⊬ ⍜⏁⊑⟒⍀ ⏃⎐⟟⏃⋏ ⌇⌿⟒☊⟟⟒⌇. ⟟⋏ ⏁⟒⍀⋔⌇ ⍜⎎ ⊑⍜⍙ ⟟⏁ ⍙⍜⍀☍⌇, ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⎍⌇⟒ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎅⍜⍙⋏⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇ ⏁⍜ ⌿⍀⍜⎅⎍☊⟒ ⏃ ⎎⎍⌰⌰ ¾ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁ ⌇⎍⌿⌿⍜⍀⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀, ⌰⟒⏃⎐⟟⋏☌ ⍜⋏⌰⊬ ⏃ ⍾⎍⏃⍀⏁⟒⍀ ⏁⍜ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎍⌿⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒. ⎅⍜⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟟⌇, ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇ ⌿⍀⍜⎅⎍☊⟒ ⏃ “⎎⟟☌⎍⍀⟒ 8” ⋔⍜⏁⟟⍜⋏, ☍⟒⟒⌿⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟒⋔ ⊑⍜⎐⟒⍀⟒⎅ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀.

⏃⋏⎅ ⍙⟟⏁⊑ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⟟⋏ ⋔⟟⋏⎅, ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⎅⍜⋏⏁ ⍀⟒⏃⌰⌰⊬.. “⎅⍜” ⏁⊑⏃⏁. ⟟⏁’⌇ ⌇⎍☊⊑ ⏃ ⌇⏁⍀⏃⋏☌⟒ ⏁⊑⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⟟⏁ ⎍⌇⟒⎅ ⏁⍜ ⏚⟒ ⏃⌇⌇⎍⋔⟒⎅ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⊑⏃⎅ ⏃ *⎐⟒⍀⊬* ⟒⍾⎍⏃⌰ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁ ⌇⎍⌿⌿⍜⍀⏁. ⏃⌇ ⟟⋏, ⏚⍜⏁⊑ ⏃⋏ ⎍⌿⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒ ⏃⋏⎅ ⎅⍜⍙⋏⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒ ⍙⟟⋏☌ ⏚⟒⏃⏁ ⍙⍜⎍⌰⎅ ⌇⎍⌿⌿⍜⍀⏁ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⏃⋔⟒ ⏃⋔⍜⎍⋏⏁ ⍜⎎ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁ ⎍⌿ ⏃⋏⎅ ⎅⍜⍙⋏ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀. ⋔⏃⋏⊬ ⌇⏁⎍⎅⟟⟒⌇ ⏃⌇⌇⎍⋔⟒⎅ ⏁⊑⏃⏁, ⌇⟟⋔⌿⌰⊬ ⏚⟒☊⏃⎍⌇⟒ ⟟⏁⌇ ⟒⌖⏃☊⏁⌰⊬ ⊑⍜⍙ ⋔⏃⋏⊬ ⟟⋏⌇⟒☊⏁⌇ ⎅⍜ ⟟⏁. ⌇⟟⋔⌿⌰⊬ ⌿⎍⏁, ⟟⏁⌇ ⎍⋏⏁⍀⎍⟒. ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⎎⍜⍀⋔⟒⎅ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⟒⋏⏁⟟⍀⟒ ⏚⏃⌇⟒ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⌇⏁⍀⎍☊⏁⎍⍀⟒ ⌇⟟⋔⟟⌰⏃⍀⌰⊬ ⏁⍜ ⌇⍜⋔⟒⏁⊑⟟⋏☌ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⏃ ⊑⏃⍙☍ ⋔⍜⏁⊑. ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⏃⍀⟒ ⟟⋏☊⍀⟒⎅⟟⏚⌰⊬ ⎍⋏⟟⍾⎍⟒ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⍙⏃⊬, ⋔⏃☍⟟⋏☌ ⏃⌰⌰ ⍜⎎ ⋔⊬ ⍙⍜⍀☍…. ⟟⋏⏁⟒⍀⟒⌇⏁⟟⋏☌.

⎍⋏⎅⟒⍀⌇⏁⏃⋏⎅⏃⏚⌰⊬, ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⊑⏃⌇ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍀⟒⌇⎍⌰⏁ ⍜⎎ ⏃ *⎐⟒⍀⊬* ⋏⟒⍙ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒ ⌇⏁⍀⎍☊⏁⎍⍀⟒ ⍙⟟⏁⊑⟟⋏ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⍜⏁⊑⟒⍀ ⏃⎐⟟⏃⋏⌇ ⎅⍜⋏⏁ ⌇⊑⏃⍀⟒. ⌇⎍⌇⏁⏃⟟⋏⟒⎅ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏃⎐⟟⏃⋏ ⌇⌿⟒☊⟟⟒⌇ ⟟⌇ ⌿⍀⍜⎅⎍☊⟒⎅ ⏁⊑⍀⍜⎍☌⊑ ⏁⍙⍜ ⋔⏃⟊⍜⍀ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒ ☌⍀⍜⎍⌿⌇, ⏁⊑⟒ ⌿⟒☊⏁⍜⍀⏃⌰⟟⌇ ⋔⏃⟊⍜⍀, ⏃⋏⎅ ⌇⎍⌿⍀⏃☊⍜⍀⏃☊⍜⟟⎅⟒⎍⌇. ⟒⌇⌇⟒⋏⏁⟟⏃⌰⌰⊬, ⏁⊑⟒⌇⟒ ⏁⍙⍜ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒⌇ ⏃⌰⌰⍜⍙ ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⏁⍜ ⌇⌿⟒⋏⎅ ⏁⊑⟒ ⋔⏃⟊⍜⍀⟟⏁⊬ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⟒⋏⟒⍀☌⊬ ⍜⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎅⍜⍙⋏⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒ ⏃⋏⎅ ⎍⌿⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒ ⋔⟒☊⊑⏃⋏⟟⌇⋔⌇ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍙⟟⋏☌. ⟟⋏ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇, ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⏁⍀⏃⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⌿⎍⏁ ⍜⋏ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⌿⟒☊⏁⍜⍀⏃⌰⟟⌇ ⋔⏃⟊⍜⍀ ⟟⌇ ⟟⋏ ⎎⏃☊⏁ ⏁⊑⟒ *⌰⍜⍙⟒⌇⏁* ⍀⟒☊⍜⍀⎅⟒⎅ ⟟⋏ *⏃⋏⊬* ⎎⌰⊬⟟⋏☌ ⏚⟟⍀⎅. ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⟟⌇ ⟟⋏⏁⟒⍀⟒⌇⏁⟟⋏☌ ⎅⎍⟒ ⏁⍜ ⊑⍜⍙ ⋔⎍☊⊑ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁ ⟟⌇ ⌇⎍⌿⌿⍜⍀⏁⟒⎅ ⏚⊬ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎅⍜⍙⋏⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒, ⎅⟟☊⏁⏃⏁⟒⎅ ⏚⊬ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒ ⟒⋏⏁⟟⍀⟒⌰⊬, ⏃⌇ ⋔⟒⋏⏁⟟⍜⋏⟒⎅ ⟒⏃⍀⌰⟟⟒⍀. ⋔⟒⏃⋏⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎍⌿⌇⏁⍀⍜☍⟒, ⍙⊑⟟☊⊑ ⌇⎍⌿⌿⍜⍀⏁⌇ ⎐⟒⍀⊬ ⌰⟟⏁⏁⌰⟒ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁, ⊑⍜⌰⎅⌇ ⌇⏁⍀⏃⟟⋏ ⏃⏁ ⏃ ⌿⍀⍜⌿⍜⍀⏁⟟⍜⋏⏃⌰⌰⊬ ⌰⏃⍀☌⟒⍀ ⏃⋔⍜⎍⋏⏁ ⏁⊑⏃⋏ ⏃⋏⊬ ⍜⏁⊑⟒⍀ ⏚⟟⍀⎅ ⌇⌿⟒☊⟟⟒⌇… ⏁⊑⏃⏁⌇ ⌇⍜ ⎎⎍☊☍⟒⎅ ⎍⌿.

⏁⊑⟒⌇⟒ ⏃⎅⏃⌿⏁⏃⏁⟟⍜⋏⌇ ⏁⍜ ☍⟒⟒⌿ ⊑⍜⎐⟒⍀⟟⋏☌ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀ ⎎⍜⍀ ⏃⌇ ⌰⍜⋏☌ ⏃⌇ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⎅⍜ ⋔⟒⏃⋏⌇ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⏃⋏ ⟟⋏☊⍀⟒⎅⟟⏚⌰⊬ ⎍⋏⟟⍾⎍⟒ ⏃⎅⏃⌿⏁⏃⏁⟟⍜⋏- ⋏⍜ ⏃⌰⎍⌰⏃. ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⌰⎍⌰⏃ ⟟⌇ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⋔⏃⌰⌰ ☌⍀⍜⎍⌿⟟⋏☌ ⍜⎎ ⎎⟒⏃⏁⊑⟒⍀⌇ ⏃⌰⍜⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⋏⏁⟒⍀⟟⍜⍀ ⟒⎅☌⟒ ⍜⎎ ⏃ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁⟒⎅ ⏚⟟⍀⎅’⌇ ⍙⟟⋏☌. ⟟⏁ ⎎⎍⋏☊⏁⟟⍜⋏⌇ ⏃ ⌰⍜⏁ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⏃ “⏁⊑⎍⋔⏚” ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍙⏃⊬ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⟟⏁ ⌇⟟⏁⌇ ⟟⋏ ⏁⟒⍀⋔⌇ ⍜⎎ ⏚⍜⋏⟒ ⌇⏁⍀⎍☊⏁⎍⍀⟒, ⏃⋏⎅ ⏁⊑⏃⏁⌇ ⊑⍜⍙ ⏃ ⌇⊑⟟⎎⏁⟒⍀ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⋔⟒ ⍙⍜⎍⌰⎅ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⏁⍜ ⏁⊑⟟⋏☍ ⏃⏚⍜⎍⏁ ⟟⏁ ⏁⍜ ⎎⍜⍀⋔ ⍜⋏⟒ ☊⍜⍀⍀⟒☊⏁⌰⊬. ⟟⋏ ⍜⏁⊑⟒⍀ ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ☊⏃⌿⏃⏚⌰⟒ ⍜⎎ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁, ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⌰⎍⌰⏃ ⎎⎍⋏☊⏁⟟⍜⋏⌇ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⌰⏃⏁⌇ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇ ⍜⎎ ⏃⋏ ⏃⟟⍀☊⍀⏃⎎⏁ ☊⏃⍀⍀⟟⟒⍀, ⏁⍜ ☊⍜⋏⏁⍀⍜⌰ ⌇⌿⟒⟒⎅. ⏃⌰⎍⌰⏃⌇ ☊⏃⋏ ⏚⟒ ⋔⏃⋏⟟⌿⎍⌰⏃⏁⟒⎅ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⏃⋔⟒ ⍙⏃⊬, ⏁⍜ ⏃⌇⌇⟟⌇⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏃ ⌇⍜⎎⏁⟒⍀ ⌰⏃⋏⎅⟟⋏☌. ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⌇⟟⋔⌿⌰⊬…. ⎅⍜⋏⏁ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⍜⋏⟒! ⏁⊑⟒ ⎅⟟☌⟟⏁ ⟟⌇ ⏁⊑⟒⍀⟒, ⏚⎍⏁ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎎⎍⋏☊⏁⟟⍜⋏ ⟟⌇ ⟒⋏⏁⟟⍀⟒⌰⊬ ⎐⟒⌇⏁⟟☌⟟⏃⌰. ⏃ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⌇⟒⌇⏃⋔⍜⟟⎅ ⏚⍜⋏⟒⌇ ⏃⍀⟒ ⟒⌇⌇⟒⋏⏁⟟⏃⌰⌰⊬ ⎎⎍⌇⟒⎅ ⍙⊑⟒⍀⟒ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⋏⟒⟒⎅ ⏁⍜ ⏚⟒, ⏃⋏⎅ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⎅⍜⋏⏁ ⎍⌇⟒ ⏃⋏⊬ ⟒⌖⏁⍀⏃ ⊑⟒⌰⌿ ⍙⟟⏁⊑ ⌰⏃⋏⎅⟟⋏☌ ⌇⟟⋏☊⟒ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⏃⍀⟒ ⟟⋏ ⎎⎍⌰⌰ ☊⍜⋏⏁⍀⍜⌰ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⌿⟒⟒⎅ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ☍⟒⟒⌿ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀. ⟟ ⌇⏁⟟⌰⌰ ☍⟒⟒⌿ ⟟⏁, ⊑⍜⍙⟒⎐⟒⍀, ⎎⍜⍀ ⋔⟒⏃⌇⎍⍀⟒⋔⟒⋏⏁ ⌿⎍⍀⌿⍜⌇⟒⌇. ⍙⟟⏁⊑ ⏃⋏ ⏃⌰⎍⌰⏃, ⟟ ���⏃⋏ ☍⟒⟒⌿ ⏁⍀⏃☊☍ ⍜⎎ ⍙⊑⟒⍀⟒ ⏁⍜ ⌿⌰⏃☊⟒ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏚⍜⎍⋏⎅⏃⍀⊬ ⏚⟒⏁⍙⟒⟒⋏ ⌿⍀⟟⋔⏃⍀⊬ ⏃⋏⎅ ⋔⏃⍀☌⟟⋏⏃⌰ ☊⍜⎐⟒⍀⏁⌇.

⟟⋏ ⏁⟒⍀⋔⌇ ⍜⎎ ⊑⍜⍙ ⏃⌰⌰ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⍙⍜⍀☍⌇ ⍜⎍⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⟒⋏⎅, ⏁⊑⟒ ⟒⋏⎅ ⍀⟒⌇⎍⌰⏁ ⟟⌇ ⏃ ⏚⟟⍀⎅ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⌇ ⌀.16 ⍜⋉ ⏃⋏⎅ ☊⏃⋏ ⏚⟒⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇ ⊜ ⏁⟟⋔⟒⌇ ⌿⟒⍀ ⋔⟟⋏⎍⏁⟒, ⏃☊⊑⟟⟒⎐⟟⋏☌ ⏃ ⊑⍜⎐⟒⍀⟟⋏☌ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⋔⍜⎅⟒⍀⋏ ⎅⏃⊬ ⟟⋏⋏⍜⎐⏃⏁⟟⍜⋏⌇ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⊑⟒⌰⟟☊⍜⌿⏁⟒⍀ ⟟⋏⎅⎍⌇⏁⍀⊬ ☊⏃⋏ ⍜⋏⌰⊬ ⎅⍀⟒⏃⋔ ⍜⎎ ⏃☊⊑⟟⟒⎐⟟⋏☌. ⍀⟒⌇⟒⏃⍀☊⊑ ⟟⋏⏁⍜ ⊑⍜⍙ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏚⟒⌇⏁ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⎎⌰⊬ ⎐⟒⍀⌇⎍⌇ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍙⍜⍀⌰⎅’⌇ ⋔⍜⌇⏁ ⏃⎅⎐⏃⋏☊⟒⎅ ⋔⟟☊⍀⍜ ⊑⟒⌰⟟☊⍜⌿⏁⟒⍀⌇ ⌇⎍☌☌⟒⌇⏁⌇ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⏃⍀⟒ ☊⏃⌿⏃⏚⌰⟒ ⍜⎎ ⏚⟒⟟⋏☌ ⎍⌿ ⏁⍜ ⊖% ⋔⍜⍀⟒ ⟒⎎⎎⟟☊⟟⟒⋏⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏁⟒⍀⋔⌇ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌿⍜⍙⟒⍀ ⋏⟒⟒⎅⟒⎅ ⎎⍜⍀ ⌰⟟⎎⏁. ⏁⊑⟒⌇⟒ ⌇⋔⏃⌰⌰ ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⌿⟒⍀⎎⟒☊⏁⟒⎅ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⍀��� ⍜⎎ ⋏⏃⏁⎍⍀⏃⌰, ⌇⎍⌇⏁⏃⟟⋏⏃⏚⌰⟒ ⊑⍜⎐⟒⍀⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⊑⎍⋔⏃⋏⌇ ⌇⏁⍀⎍☌☌⌰⟒ ⏁⍜ ⎅⍀⟒⏃⋔ ⍜⎎, ⏃⋏⎅ ⟟ ☊⏃⋏ ⍜⋏⌰⊬ ⊑⍜⌿⟒ ⏁⍜ ⟒⎐⟒⋏ *⌰⍜⍜☍* ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⍜⋏⟒ ⌇⍜⋔⟒⎅⏃⊬. ⟟’⌰⌰ ⏚⟒ ⊑⍜⋏⟒⌇⏁, ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⟟⌇ ⋏⍜⏁ ⟒⌖⏃☊⏁⌰⊬ ⋔⊬ ⋔⏃⟟⋏ ☊⍜⋏☊⟒⍀⋏ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⍙⍜⍀☍, ⏚⎍⏁ ⟟⎎ ⟟ ☊⏃⋏ ⌇⏁⎍⋔⏚⌰⟒ ⎍⌿⍜⋏ ⟟⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌿⍀⍜☊⟒⌇⌇, ⟟⏁ ⍙⟟⌰⌰ ⏚⟒ ⏃ ⎅⍀⟒⏃⋔ ☊⍜⋔⟒ ⏁⍀⎍⟒.

⎎⎍☊☍, ⟟ ⏃⌰⋔⍜⌇⏁ ⎎⍜⍀☌⍜⏁ ⍙⊑⏃⏁ ⟟ ⍙⏃⌇ ⏃☊⏁⎍⏃⌰⌰⊬ ☌⍜⟟⋏☌ ⏁⍜ ⌇⏃⊬ ⏃⌇ ⏁⊑⟒ ⎎⎍⋏ ⎎⏃☊⏁. ⏁⍜ ⏚⟒☌⟟⋏ ⟒⌖⌿⌰⏃⟟⋏⟟⋏☌, ⏃⋏⎅ ⟟⏁ *⎅⍜⟒⌇* ⏁⏃☍⟒ ⌇⍜⋔⟒ ⟒⌖⌿⌰⏃⟟⋏⟟⋏☌, ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⏃⎅⏃⌿⏁⟒⎅ ⟒⌖⏁⍀⟒⋔⟒⌰⊬ ⍙⟒⌰⌰ ⏁⍜ ⏚⏃⍀⍜⋔⟒⏁⍀⟟☊ ☊⊑⏃⋏☌⟒⌇ ⏃⋏⎅ ⋔⏃⟊⍜⍀ ⏃⌰⏁⟟⏁⎍⎅⟒ ☊⊑⏃⋏☌⟒⌇. ⎅⟟⎎⎎⟒⍀⟒⋏⏁ ⌇⌿⟒☊⟟⟒⌇ ⌰⟟⎐⟟⋏☌ ⟟⋏ ⎐⏃⌇⏁⌰⊬ ⎅⟟⎎⎎⟒⍀⟒⋏⏁ ⟒⋏⎐⟟⍀⍜⋏⋔⟒⋏⏁⌇ ⏃⎅⏃⌿⏁ ⎎⍜⍀ ⌰⟟⎎⟒ ⎍⌇⟟⋏☌ ⋔⍜⍀⟒ ⌿⍜⍙⟒⍀ ⌿⟒⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌ ⏚⟒⏃⏁ ⏚⊬ ☊⊑⏃⋏☌⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟒ ⌇⟟⋉⟒ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇. ⊑⟟☌⊑⟒⍀ ⏃⌰⏁⟟⏁⎍⎅⟒ ⋔⟒⏃⋏⌇ ⌰⏃⍀☌⟒⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇, ⍙⊑⟟☊⊑ ⋔⟒⏃⋏⌇ ⎎⟒⍙⟒⍀ ⟟⌇⌇⎍⟒⌇ ⍙⊑⟒⋏ ⌰⟟⎎⏁⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟒⋔⌇⟒⌰⎐⟒⌇ ⟟⋏⏁⍜ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀ ⏃⏁ ⌰⍜⍙⟒⍀ ⏃⟟⍀ ⎅⟒⋏⌇⟟⏁⟟⟒⌇. ⌇⋔⏃⌰⌰⟒⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇, ⍜⎎ ☊⍜⎍⍀⌇⟒, ⎎⍜⍀ ⏃ ⌇⟟⋔⟟⌰⏃⍀ ⟒⎎⎎⟒☊⏁ ⟟⋏ ⊑⟟☌⊑⟒⍀ ⏃⟟⍀ ⎅⟒⋏⌇⟟⏁⟟⟒⌇. ⟒⌇⌇⟒⋏⏁⟟⏃⌰⌰⊬, ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⍙⏃⋏⏁ ⏁⍜ ⟒⌰⟟⋔⟟⋏⏃⏁⟒ ⏃⋏⊬ ⏃⋏⎅ ⏃⌰⌰ ⍙⟟⋏⎅ ⍀⟒⌇⟟⌇⏁⏃⋏☊⟒ ⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟒ *⟒⌖⏃☊⏁ ⍀⟟☌⊑⏁ ⏃⋔⍜⎍⋏⏁* ⏁⍜ ☍⟒⟒⌿ ⏁⊑⟒⋔⌇⟒⌰⎐⟒⌇ ⌇⏁⟒⏃⎅⊬…. ⎎⍜⍀ ⋏⟒���⏁⏃⍀. ⍙⊑⏃⏁ ⏃ ⍙⍜⋏⎅⟒⍀⎎⎍⌰ ⍙⏃⊬ ⏁⍜ ⌰⟟⎐⟒.

⎍⋏⎅⟒⍀⌇⏁⏃⋏⎅⏃⏚⌰⊬, ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⌰⟒⏃⎅⌇ ⎍⌇ ⏁⍜ ⏁⊑⟒ ☊⎍⏁⟒⌇⏁ ⏁⊑⟟⋏☌ ⟟ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⊬⟒⏁ ⌰⟒⏃⍀⋏⟒⎅ ⏃⏚⍜⎍⏁ ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇. ⏁⊑⟒⊬…. ☌⟒⏁ ⏁⊑⟟⌇…. ⌇⊑⏃☍⟒ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⎅⍜☌⌇ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⟟⍀ ⎅⎍⍀⟟⋏☌ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⟟⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍀⏃⟟⋏. ⟟⌇⋏⏁ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⏃⎅⍜⍀⏃⏚⌰⟒???? ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⏁⍜ ⌇⊑⟒⎅ ⍙⏃⏁⟒⍀ ⏁⍜ ⏃⎐⍜⟟⎅ ☌⏃⟟⋏⟟⋏☌ ⏁⍜⍜ ⋔⎍☊⊑ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁ ⟟⋏ ⍙⏃⏁⟒⍀ ⎅⍀⍜⌿⌇ ⌇⍜ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ☊⏃⋏ ☊⍜⋏⏁⟟⋏⎍⟒ ⌇⟟⌿⌿⟟⋏☌ ⋏⟒☊⏁⏃⍀ ☊⍜⋔⎎⍜⍀⏁⏃⏚⌰⊬!!!! ⍙⊑⟒⋏ ⏁⊑⟒ ⍙⏃⏁⟒⍀ ⎅⍀⍜⌿⌰⟒⏁⌇ ☊⍜⌰⌰⟒☊⏁, ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ☊⏃⋏ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏚⟟⍀⎅ ⎅⍜⍙⋏ ⟒⋏⍜⎍☌⊑ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⋔⎍⌇⏁ ☊⊑⏃⋏☌⟒ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⌿⍜⌇⏁⎍⍀⟒. ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⎅⍜ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⏚⊬ ⌇⏁⏃⍀⏁⟟⋏☌ ⏁⍜ ���⌰⊬ ⎎⎍⌰⌰⊬ ⊑⍜⍀⟟⋉⍜⋏⏁⏃⌰⌰⊬, ⏚⟒☌⟟⋏⋏⟟⋏☌ ⏃⍀⍜⎍⋏⎅ 38% (38%!!!! ⍜⎐⟒⍀ ⏃ ⏁⊑⟟⍀⎅ ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⏚⍜⎅⊬ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁ ⟟⋏ ⌰⟟⏁⏁⌰⟒ ⎅⍀⍜⌿⌇ ⍜⎎ ⍙⏃⏁⟒⍀ ⌇⟟⏁⏁⟟⋏☌ ⍜⋏ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⏚⏃☊☍!!!!) ⍜⎎ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟒⟟☌⊑⏁. ⏁⊑⟒⊬ ⏃⌰⌇⍜ ⊑⏃⎐⟒ ⏁⍜ ⏚⟒⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⍙⟟⋏☌⌇ ⎎⏃⌇⏁⟒⍀ (⊬⟒⌇, ⎎⏃⌇⏁⟒⍀ ⏁⊑⏃⋏ *80 ⏚⟒⏃⏁⌇ ⌿⟒⍀ ⋔⟟⋏⎍⏁⟒….*), ⏃⋏⎅ ⍀⟒⎅⎍☊⟒ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⋏☌⌰⟒ ⍜⎎ ⋔⍜⏁⟟⍜⋏ ⟟⋏ ⊑⟒⏃⎐⟟⟒⍀ ⍀⏃⟟⋏ ⏁⍜ ⏃⎐⍜⟟⎅ ⏁⊑⟒ ⟒⌖⏁⍀⏃ ⌇⏁⍀⏃⟟⋏ ⍜⋏ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒⌇! ⟟⏁’⌇ ⏃ ⍙⍜⋏⎅⟒⍀⎎⎍⌰ ⏁⊑⟟⋏☌ ⏁⍜ ⌇⟒⟒ ⟟⋏ ⏃☊⏁⟟⍜⋏, ⏃⋏⎅ ⟟ ⌇⎍☌☌⟒⌇⏁ ⎎⟟⋏⎅⟟⋏☌ ⎐⟟⎅⟒⍜⌇ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⌇⊑⍜⍙ ⊬⍜⎍ ⏃☊☊⎍⍀⏃⏁⟒⌰⊬ ⍙⊑⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ⌰⍜⍜☍⌇ ⌰⟟☍⟒.

⌰⍜⍜☍, ⟟ ⟊⎍⌇⏁ ⍀⟒⏃⌰⌰⊬ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⎅⍜☌⌇. ⏃⋏⎅ ⟟⋔ ⎎⟟⋏⎅⟟⋏☌ ⟟⋔ ⌇⏁⏃⍀⏁⟟⋏☌ ⏁⍜ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⟊⎍⌇⏁ ⏃⌇ ⋔⎍☊⊑. ⏁⊑⟒⍀⟒⌇ *⌇⍜* ⋔⎍☊⊑ ⏁⍜ ⏁⊑⟒⋔. ⏁⊑⟒⍀⟒’⌇ ⍜⏁⊑⟒⍀ ⏁⊑⟟⋏☌⌇ ⟟ ⎅⟟⎅⋏⏁ ⋔⟒⋏⏁⟟⍜⋏, ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⊑⍜⍙ ⋔⍜⌇⏁ ⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ☍⋏⟒⟒⌇ ⏃⍀⟒ ⟟⋏⏁⟒⍀⋏⏃⌰, ⍜⍀ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏃⌰⎍⌰⏃ ⟟⌇ ⏃⌰⌇⍜ ☍⋏⍜⍙⋏ ⏃⌇ ⏁⊑⟒ ⏚⏃⌇⏁⏃⍀⎅ ⍙⟟⋏☌. ⏚⎍⏁ ⎎⍀⍜⋔ ⊑⏃⎐⟟⋏☌ ⏁⍜ ⎍⌇⟒ ⋔⏃⌇⌇⟟⎐⟒⌰⊬ ⏁⟒☊⊑⋏⟟☊⏃⌰ ⌿⊑⍜⏁⍜☌⍀⏃⌿⊑⊬ ⋔⟒⏁⊑⍜⎅⌇ ⏁⍜ ☊⏃⌿⏁⎍⍀⟒ ⎐⟒⍀⊬ ⌇⋔⏃⌰⌰ ⋔⍜⏁⟟⍜⋏⌇ ⏁⊑⏃⏁ ⏃⋏⊬ ⍜⏁⊑⟒⍀ ⎎⌰⟟☌⊑⏁ ⏚⟟⍀⎅ ⍙⍜⎍⌰⎅ ⏚⟒ ☌⟒⋏⎍⟟⋏⟒⌰⊬ ⟟⋏☊⏃⌿⏃⏚⌰⟒ ⍜⎎, ⏁⍜ ⎍⌇⟟⋏☌ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⋔⎍⌇☊⌰⟒⌇ ⋔⍜⍀⟒ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⟟⋏⌇⟒☊⏁⌇ ⏁⊑⏃⋏ ⏁⊑⟒⟟⍀ ⏃⎐⟟⏃⋏ ⎎⏃⋔⟟⌰⊬, ⊑⎍⋔⋔⟟⋏☌⏚⟟⍀⎅⌇ ⏃⍀⟒ ⟊⎍⌇⏁…. ⏃⏚⌇⍜⌰⎍⏁⟒⌰⊬ ⌇⏁⎍⋏⋏⟟⋏☌. ⟟⏁⌇ ⏃ ⍙⍜⋏⎅⟒⍀, ⍀⟒⏃⌰⌰⊬, ⊑⍜⍙ ⌇⍜⋔⟒⍜⋏⟒ ⌰⟟☍⟒ ⋔⟒ ☊⍜⎍⌰⎅ ⟒⎐⟒⍀ ☊⍜⋔⟒ ⏁⊑⟟⌇ ☊⌰⍜⌇⟒ ⏁⍜ ⏚⟒⟟⋏☌ ⏃⌇ ⏚⟒⏃⎍⏁⟟⎎⎍⌰ :)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Books on My Bookshelf

#Poop4U

Holy moly, Batman, the books on my night stand are piling up. Here’s a sample:

OUR DOGS OURSELVES, by Alexandra Horowitz. (Released September 3rd, but available for pre order.) This thoughtful book by the author of The Inside of a Dog and Being a Dog deserves to be read by dog lovers everywhere. I say that, full disclosure, not having read the entire book yet. An “advance readers edition” came several weeks ago, and I will admit to, at first, feeling a bit wary of how much new information it would contain. But then I started reading it, and this is, bravely and insightfully, a book that goes far beyond the usual musings about our relationship with dogs.

One early chapter is titled “Owning Dogs,” and explores our contradictory relationship with dogs–legally defined as property and yet considered by many of us to be family members and best friends. I’ve said in the past that if someone took one of my dogs it would be kidnapping, not stealing. But that’s not what the laws says. This is an issue that we’ve never adequately addressed, involving many complicated considerations, and I appreciate Horowitz’s attempts to continue a conversation about it.

Another chapter looks at our country’s spay and neuter practices–no controversy there (!). The author takes this issue on full frontal:

“For me simply to bring up the topic of de-sexing for discussion will be, in the eyes of some, impermissible. So sacred is the policy–so heartfelt (and good-hearted) is the intent behind it–that one is almost not allowed to talk about it.”

But of course, she does, and asks us to look carefully at costs and benefits of our current belief in whole-scale spaying and neutering. (Note this other article that looks at the costs of spay-neuter policies.

Our Dogs, Ourselves also takes on the biology and ethics of current breeding practices, among other topics, so expect to be engaged. Horowitz faces these controversial issues head on, and I love her for it. In subsequent posts I’ll no doubt talk about these issues, perhaps agreeing or disagreeing with the author, but grateful nonetheless that she is talking about them.

Last thing: Horowitz or her editors deserve an award for “best titles ever,” after The Inside of a Dog (from Mark Twain’s “Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog, it’s too dark to read.”) Our Dogs, Ourselves is, of course, reminiscent of Our Bodies, Ourselves. Kudos.

TRANSFORMING TRAUMA: Resilience and Healing Through Our Connections with Animals, edited by Philip Tedeschi and Molly Anne Jenkins.

Well, this is a fundamental switch from a book like the one above, but I highly recommend it to people who are interested in trauma recovery, especially in relation to animal-assisted interactions and therapy. Those of you who have read The Education of Will are aware that trauma is a central theme is my life’s story, so this is a book that speaks to me professionally and personally. What I like about the book is its integration of kindness and benevolence, along with lots and lots of good, solid science that backs up what we know, and don’t know, about the impact of human-animal interactions in the recovery of trauma.

Actually, “The impact of human-animal interactions in the recovery of trauma” is title of the first chapter, whose lead author is Marguerite O’Haire (who I refer to as “The Woman Whose Talks Should Never Be Missed”). Seriously, this chapter is worth the price of the book for its summary of evidence-based research, and introducing (to most of us), the concept of “bio-affiliative safety”, in which other animals allow trauma victims to turn off their vigilance and mechanisms of defense.

This is not beach reading. For example, in Chapter One, relating to bio-affiliative safety: “In Porges’ explorations of the polyvagal system and the concept of neuroception, we can begin to understand how the presence of a nonhuman animal interaction may offer critical information . . . “.

But that’s exactly why I am a fan of this work–we need to continue to push beyond the feel-good, rosy picture of all animals helping all people all the time, and support serious science that looks at exactly how, and how not, other animals can help us humans recover from trauma.

The other perspective that is vital in Transforming Trauma is its emphasis on never using animals in a way that discomforts or exploits them. Here, here.

DOG BEHAVIOR, MODERN SCIENCE AND OUR CANINE COMPAIONS, by James Ha and Tracy Campion. Also not a beach reach, this book is a treasure trove of information for people who are interested in the integration of science and dog training. It includes a great deal of history and analysis of animal behavior studies, from Darwin’s interest in canine skulls, to cost-benefit analyses of decision making. It’s both practical (lots of stories from the author’s case studies) and theoretical (kin selection and dogs–who talks about that?).

What I love most about this book is based in part on my shared academic experience with one of the authors, James Ha. Both of us were trained as ethologists, and both of us spent years studying animal behavior in a general sense before we became involved in the dog world. I’ve always believed that to truly understand dog behavior, you need to understand the full range of behavior found in the animal world, so that you can put dogs in perspective. That’s exactly what this book does, and that’s why, for example, reading the chapter titled “Debunking Dominance: Canine social structure and behavioral ecology” is like a breath of fresh air. The chapter begins thus: “The social structure of a species, and hence their social behavior, is based upon resource distribution”. Oh, oh, music to my ears to see this in print. This is such an important concept to grasp, as is the fact that individuals of very closely related species can behave very differently, in part based on resource distribution. (Compare male-dominate chimps versus matriachal bonobos for example.)

Anyone who argues against “dominance or force-based training” would profit from reading this chapter, from its distinction between dominance and aggression, to the evidence that wolf packs in the wild are not “dominated by a alpha” but led by parent-like adults who take on roles of defense and hunting/provisioning, primarily based on sex.

There’s lots and lots more in this book, and I look forward to reading more of it, I’m thinking it will be a great way to start my every morning. (I tend to read fiction at night, non-fiction in the morning. You?)

GOOD AS A GIRL: A MEMOIR, by Ray Olderman. Ready for a paradigm shift? This book has nothing, absolutely nothing to do with dogs, but it holds a special place in my heart because it was written by a man who saved my soul in college. Quite literally. I was taking his class in literature at UW-Madison and working part time at the Primate Center. Long story, but at that time, the housing conditions for the monkeys at the Center were profoundly different than they are now. And pretty awful. When I went to the someone in charge to talk about what I felt were abuses, he literally told me “There is no biological evidence that monkeys can feel pain.” Yup, that’s what he said, in the mid 1980’s. I had thought that perhaps I could have some effect on the way the monkeys were treated, but it became clear that my ability to do so was negligible.

I couldn’t quit, I desperately needed the money, and I mean desperately. I could barely afford to eat. And yet working there violated everything I believed in. I stopped sleeping, and had a hard time just getting through the day. Ironically, in my literature class we were reading a book about a man who thought he could change a corrupt system by working within it, but was eventually destroyed by it. I finally went to see my professor, Ray Olderman and told him I was living the life we were reading about it. And it was killing me. And I couldn’t quit, I was beyond broke and there were no jobs available at that time of year. He hired me on the spot, finding some spare money to help him with grading. I will never forget it, and will always be grateful.

And so, I admit to a profound lack of objectivity about Ray’s book. But here’s the thing. I loved the book. Ray’s mother had wanted a girl, and had no pretense that she was disappointed when Ray turned out to be a boy. And so, at age eight, he vowed to her that he’d be “as good as a girl”. We follow Ray throughout his life trying to understand the female perspective while negotiating the complexities of Madison WI in the 70’s and 80’s during a time of profound cultural change.

If you’re interested in a delightful memoir about a guy who “couldn’t keep his mouth shut,” fought the system all of his life while doing all he could to understand women, this book is for you.

MEANWHILE, back on the farm: This weekend seemed to be a celebration of small, flying animals. This bee and butterfly kept displacing each other until they finally settled into feeding on opposite sides of the Hyssop flower.

Here’s the butterfly by itself; it appears to be a species in the Checkerspot group, but I’m not confident to say which one exactly.

This is one of my favorite insects, a hummingbird moth. Check out the video in the link, it’s really fun.

And here’s the source of its mimicry, still finding nutrition in this tacky looking Bee Balm flower.

Swallowtails everywhere. Monarchs too, although I could never get a shot. I hear that Monarchs are doing better this summer (yay!), and it’s also wonderful to see so many bees out. Finally! The wet spring and early summer was so hard on them, and they have enough challenges right now.

What brought you joy this week, whether a new book, animals or plants? You know I’d love to hear.

Poop4U Blog via www.Poop4U.com Trisha, Khareem Sudlow

0 notes

Text

Yes, Virginia, bluebells also grow in Indiana

National Park Service photo

Geographically speaking, my always stunning crop of Virginia Bluebells got to Indiana from a plant nursery in West Virginia. But as is often the case in the plant world, geography, history and personal preference get a little tangled in the journey.

Yes, the Virginia Bluebells name came from their 17th century discovery in the Colony of Virginia, but they are actually native from New York to Alabama and west to Kansas and Minnesota – and showing up in 18 species along the way.

Photo by Monticello

If it’s a more specific date you require, American Father Figure and Garden Guy Thomas Jefferson wrote of the Monticello bluebells in his garden book on April 16,1766, reporting “a bluish colored, funnel-formed flower in the lowlands in bloom.”

That a man with such a gift for words would so understate the beauty of my favorite native plant is almost criminal. Come on Tom! Where’s the passion in “bluish colored and funnel-formed?”

I, for one, desperately long for my Virginia bluebells arrival every spring, stomping around in the fat brown layer of dead magnolia leaves that fell on my patch looking for some truth.

It’s March Magic. Winter is history. Their leaves first poke through the leaf decay in dark shades of purple but turn a pleasant green as they mature. The “funnel-formed flowers,” and I will give Thomas Jefferson his due on that, flow from a rich pink to their heavenly shade of baby blue, although that can vary according to the soil from whence they emerge.

That color change is the result of changes in the pH of the cell sap, although, like hydrangeas, Virginia Bluebells grown in acid soils will turn a deeper shade of blue and rise maybe 14 inches above a bleak, love-starved, late-winter landscape.

Pulmonaria

Moving deeper into the plant history, such flower color change is fairly common in the bluebell-borage family. And early garden experts confused bluebells with pulmonaria, which offers the same flow of pink and blue.

To help ease any color confusion, Albrecht Roth, a German botanist, placed the Virginia Bluebells in a new genus, mertensia, in honor of another German botanist, F. C. Mertens. Hello Mertensia virginica!

Mertensia jellyfish

Here’s another fact that can win you some smiles at the next garden club meeting. Merten’s son, K. H. Mertens, had a group of jellyfish named mertensia in his honor, a rare double-play in the plant and underwater worlds.

Such plant-name designations have always seemed arbitrary to me – and I want in. I live – or perhaps may have to die for – the day any spring-blooming ephemeral with sexy green leaves and pink-blue flowers is named Hilltensia hoosierca.

Given its colors, early pioneers to the New World also thought Virginia bluebells to be lungwort, which had been used to treat lung diseases on the far side of the ocean. It didn’t work over here. Dead men tell no tales.

Another early blue name was “oyster leaf,” but was apparently not a hit item in the Colonial diet. Another title was “Mountain blue cowslip,” about as descriptive as Jefferson’s “funnel-formed” flowers.

How do I love thee, Virginia bluebell? Let me count the ways.

Photo by Barry Glick

1. My first in-your-face experience with Virginia bluebells was a monster patch spread out below a massive oak tree with its bare arms lifted toward the sun, a damn near religious experience. Hell, it was a religious experience.

2. The leaves and flowers buddy up well on the early spring calendar with Bloodroot, crocus and Celandine poppies, offering a woodsy palette of pink, blue, purple, yellow, white and green.

3. Their leaves show up about the same time as the NCAA basketball tournament, so if your beloved team loses you have a good excuse to go outside to the garden and shed tears where no one can see you.

Photo by Monticello

4. Given their “funnel-formed” flowers – and OK, maybe Thomas Jefferson was on to something – their pollinators are a flying circus of honeybees, bumblebees, Anthophoid bees, mason bees, Halictid bees, Syrphid flies, butterflies and Sphinx moths. Yes, good people get paid to research all that stuff.

5. Those same people also report Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds will also occasionally stick their noses into “funnel-formed” Virginia bluebells, an event for which I would gladly pay $10 to sit and watch on a sunny Spring day in April and May.

6. Leaving little mess behind, Virginia bluebells go away by early summer, dropping exactly four seeds (the experts call them “nutlets”) per flower to propagate the species. These small nutlets – politically speaking and otherwise – are ovoid and flattened on one side, their surfaces minutely wrinkled.

7. Virginia bluebells can be purchased as nutlets or in bare root divisions. My naked roots came from Sunshine Farm and Gardens in West Virginia where Forever Hippie Barry Glick has held forth in very remote splendor for more than 40 years.

8. Virginia bluebells are not forever. They can die out in four or five years to be replaced by their own nutlets, store-bought nutlets or root divisions, but no matter their entry, they always leave us better for the experience.

More photo credits: jellyfish, Monticello photos. Other photos by the author.

Yes, Virginia, bluebells also grow in Indiana originally appeared on GardenRant on March 25, 2019.

from Gardening https://www.gardenrant.com/2019/03/yes-virginia-bluebells-also-grow-in-indiana.html via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

Yes, Virginia, bluebells also grow in Indiana

National Park Service photo

Geographically speaking, my always stunning crop of Virginia Bluebells got to Indiana from a plant nursery in West Virginia. But as is often the case in the plant world, geography, history and personal preference get a little tangled in the journey.

Yes, the Virginia Bluebells name came from their 17th century discovery in the Colony of Virginia, but they are actually native from New York to Alabama and west to Kansas and Minnesota – and showing up in 18 species along the way.

Photo by Monticello

If it’s a more specific date you require, American Father Figure and Garden Guy Thomas Jefferson wrote of the Monticello bluebells in his garden book on April 16,1766, reporting “a bluish colored, funnel-formed flower in the lowlands in bloom.”

That a man with such a gift for words would so understate the beauty of my favorite native plant is almost criminal. Come on Tom! Where’s the passion in “bluish colored and funnel-formed?”

I, for one, desperately long for my Virginia bluebells arrival every spring, stomping around in the fat brown layer of dead magnolia leaves that fell on my patch looking for some truth.

It’s March Magic. Winter is history. Their leaves first poke through the leaf decay in dark shades of purple but turn a pleasant green as they mature. The “funnel-formed flowers,” and I will give Thomas Jefferson his due on that, flow from a rich pink to their heavenly shade of baby blue, although that can vary according to the soil from whence they emerge.

That color change is the result of changes in the pH of the cell sap, although, like hydrangeas, Virginia Bluebells grown in acid soils will turn a deeper shade of blue and rise maybe 14 inches above a bleak, love-starved, late-winter landscape.

Pulmonaria

Moving deeper into the plant history, such flower color change is fairly common in the bluebell-borage family. And early garden experts confused bluebells with pulmonaria, which offers the same flow of pink and blue.

To help ease any color confusion, Albrecht Roth, a German botanist, placed the Virginia Bluebells in a new genus, mertensia, in honor of another German botanist, F. C. Mertens. Hello Mertensia virginica!

Mertensia jellyfish

Here’s another fact that can win you some smiles at the next garden club meeting. Merten’s son, K. H. Mertens, had a group of jellyfish named mertensia in his honor, a rare double-play in the plant and underwater worlds.

Such plant-name designations have always seemed arbitrary to me – and I want in. I live – or perhaps may have to die for – the day any spring-blooming ephemeral with sexy green leaves and pink-blue flowers is named Hilltensia hoosierca.

Given its colors, early pioneers to the New World also thought Virginia bluebells to be lungwort, which had been used to treat lung diseases on the far side of the ocean. It didn’t work over here. Dead men tell no tales.

Another early blue name was “oyster leaf,” but was apparently not a hit item in the Colonial diet. Another title was “Mountain blue cowslip,” about as descriptive as Jefferson’s “funnel-formed” flowers.

How do I love thee, Virginia bluebell? Let me count the ways.

Photo by Barry Glick

1. My first in-your-face experience with Virginia bluebells was a monster patch spread out below a massive oak tree with its bare arms lifted toward the sun, a damn near religious experience. Hell, it was a religious experience.

2. The leaves and flowers buddy up well on the early spring calendar with Bloodroot, crocus and Celandine poppies, offering a woodsy palette of pink, blue, purple, yellow, white and green.

3. Their leaves show up about the same time as the NCAA basketball tournament, so if your beloved team loses you have a good excuse to go outside to the garden and shed tears where no one can see you.

Photo by Monticello

4. Given their “funnel-formed” flowers – and OK, maybe Thomas Jefferson was on to something – their pollinators are a flying circus of honeybees, bumblebees, Anthophoid bees, mason bees, Halictid bees, Syrphid flies, butterflies and Sphinx moths. Yes, good people get paid to research all that stuff.

5. Those same people also report Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds will also occasionally stick their noses into “funnel-formed” Virginia bluebells, an event for which I would gladly pay $10 to sit and watch on a sunny Spring day in April and May.

6. Leaving little mess behind, Virginia bluebells go away by early summer, dropping exactly four seeds (the experts call them “nutlets”) per flower to propagate the species. These small nutlets – politically speaking and otherwise – are ovoid and flattened on one side, their surfaces minutely wrinkled.

7. Virginia bluebells can be purchased as nutlets or in bare root divisions. My naked roots came from Sunshine Farm and Gardens in West Virginia where Forever Hippie Barry Glick has held forth in very remote splendor for more than 40 years.

8. Virginia bluebells are not forever. They can die out in four or five years to be replaced by their own nutlets, store-bought nutlets or root divisions, but no matter their entry, they always leave us better for the experience.

More photo credits: jellyfish, Monticello photos. Other photos by the author.

Yes, Virginia, bluebells also grow in Indiana originally appeared on GardenRant on March 25, 2019.

from GardenRant https://www.gardenrant.com/2019/03/yes-virginia-bluebells-also-grow-in-indiana.html

0 notes

Text

Yes, Virginia, bluebells also grow in Indiana

National Park Service photo

Geographically speaking, my always stunning crop of Virginia Bluebells got to Indiana from a plant nursery in West Virginia. But as is often the case in the plant world, geography, history and personal preference get a little tangled in the journey.

Yes, the Virginia Bluebells name came from their 17th century discovery in the Colony of Virginia, but they are actually native from New York to Alabama and west to Kansas and Minnesota – and showing up in 18 species along the way.

Photo by Monticello

If it’s a more specific date you require, American Father Figure and Garden Guy Thomas Jefferson wrote of the Monticello bluebells in his garden book on April 16,1766, reporting “a bluish colored, funnel-formed flower in the lowlands in bloom.”

That a man with such a gift for words would so understate the beauty of my favorite native plant is almost criminal. Come on Tom! Where’s the passion in “bluish colored and funnel-formed?”

I, for one, desperately long for my Virginia bluebells arrival every spring, stomping around in the fat brown layer of dead magnolia leaves that fell on my patch looking for some truth.

It’s March Magic. Winter is history. Their leaves first poke through the leaf decay in dark shades of purple but turn a pleasant green as they mature. The “funnel-formed flowers,” and I will give Thomas Jefferson his due on that, flow from a rich pink to their heavenly shade of baby blue, although that can vary according to the soil from whence they emerge.

That color change is the result of changes in the pH of the cell sap, although, like hydrangeas, Virginia Bluebells grown in acid soils will turn a deeper shade of blue and rise maybe 14 inches above a bleak, love-starved, late-winter landscape.

Pulmonaria

Moving deeper into the plant history, such flower color change is fairly common in the bluebell-borage family. And early garden experts confused bluebells with pulmonaria, which offers the same flow of pink and blue.

To help ease any color confusion, Albrecht Roth, a German botanist, placed the Virginia Bluebells in a new genus, mertensia, in honor of another German botanist, F. C. Mertens. Hello Mertensia virginica!

Mertensia jellyfish

Here’s another fact that can win you some smiles at the next garden club meeting. Merten’s son, K. H. Mertens, had a group of jellyfish named mertensia in his honor, a rare double-play in the plant and underwater worlds.

Such plant-name designations have always seemed arbitrary to me – and I want in. I live – or perhaps may have to die for – the day any spring-blooming ephemeral with sexy green leaves and pink-blue flowers is named Hilltensia hoosierca.

Given its colors, early pioneers to the New World also thought Virginia bluebells to be lungwort, which had been used to treat lung diseases on the far side of the ocean. It didn’t work over here. Dead men tell no tales.

Another early blue name was “oyster leaf,” but was apparently not a hit item in the Colonial diet. Another title was “Mountain blue cowslip,” about as descriptive as Jefferson’s “funnel-formed” flowers.

How do I love thee, Virginia bluebell? Let me count the ways.

Photo by Barry Glick

1. My first in-your-face experience with Virginia bluebells was a monster patch spread out below a massive oak tree with its bare arms lifted toward the sun, a damn near religious experience. Hell, it was a religious experience.

2. The leaves and flowers buddy up well on the early spring calendar with Bloodroot, crocus and Celandine poppies, offering a woodsy palette of pink, blue, purple, yellow, white and green.

3. Their leaves show up about the same time as the NCAA basketball tournament, so if your beloved team loses you have a good excuse to go outside to the garden and shed tears where no one can see you.

Photo by Monticello

4. Given their “funnel-formed” flowers – and OK, maybe Thomas Jefferson was on to something – their pollinators are a flying circus of honeybees, bumblebees, Anthophoid bees, mason bees, Halictid bees, Syrphid flies, butterflies and Sphinx moths. Yes, good people get paid to research all that stuff.

5. Those same people also report Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds will also occasionally stick their noses into “funnel-formed” Virginia bluebells, an event for which I would gladly pay $10 to sit and watch on a sunny Spring day in April and May.

6. Leaving little mess behind, Virginia bluebells go away by early summer, dropping exactly four seeds (the experts call them “nutlets”) per flower to propagate the species. These small nutlets – politically speaking and otherwise – are ovoid and flattened on one side, their surfaces minutely wrinkled.

7. Virginia bluebells can be purchased as nutlets or in bare root divisions. My naked roots came from Sunshine Farm and Gardens in West Virginia where Forever Hippie Barry Glick has held forth in very remote splendor for more than 40 years.

8. Virginia bluebells are not forever. They can die out in four or five years to be replaced by their own nutlets, store-bought nutlets or root divisions, but no matter their entry, they always leave us better for the experience.

More photo credits: jellyfish, Monticello photos. Other photos by the author.

Yes, Virginia, bluebells also grow in Indiana originally appeared on GardenRant on March 25, 2019.

from GardenRant https://ift.tt/2Ox2ipr

0 notes

Text

Moths of Ohio- the page was brilliant

Also the guy look adorable (^-^)

Everyone please go google hummingbird moths right now. Unreal thing i saw today. Pls pls pls you won't regret it trust me.

#how is a moth flying exactly like a hummingbird#natural is something isn't it?#Look at that guy go!#Is he a bird?#no#is the a plane?#n o#he's a moth#!!!

3 notes

·

View notes