#Greg Ferarra

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

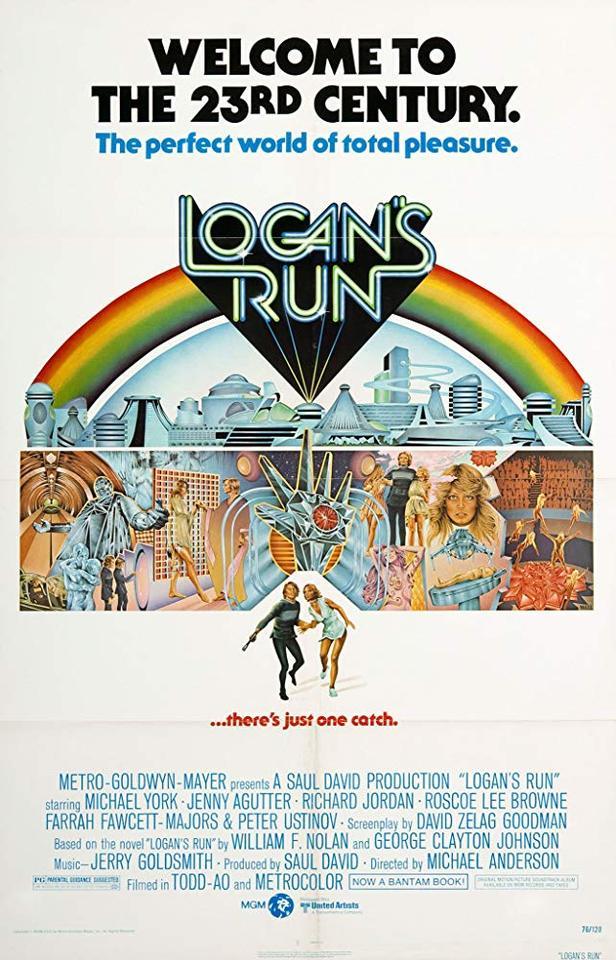

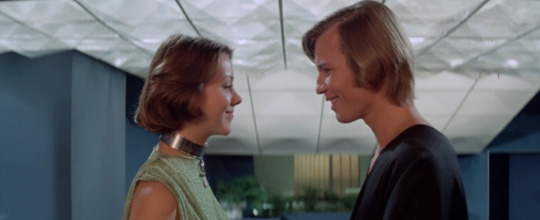

Getting Older by The Day: LOGAN’S RUN (’76) by Greg Ferrara

In the 1950s and ’60s, a doomsday idea began to gain traction: over-population. The idea, stated simply, was that human population would outpace food production. In 1968, Paul R. Ehrlich released his book, The Population Bomb , to overwhelming commercial success. The doom and gloom tome predicted everything from hundreds of millions dying in the 1970s from starvation, to London ceasing to exist by the year 2000. Yes, that actually was one of its predictions. A year before its release, another book debuted to a more restrained reception, though it too took its cue from the overpopulation fears and mixed them with fears of a youth revolution. The result was Logan's Run.

The authors of Logan's Run, William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson, begin with an impossible premise and quickly segue into a far-fetched story. The premise is that 75% of the population of the planet is under 21 by the’ 70s, then 80% by the 1980s, 85% by 1990 and so on. This is, of course, impossible. If 75% of your population is under 21, say in their mid-teens, then in 10 years they're all going to be older than 21. To get to 80%, all of them have to have twice as many children before then and more than half of the over 21 population would have to die in the same 10 years. And this would have to repeat itself every few years without missing a beat, a heartbeat that is.

The solution to all of this out of control baby production, in both book and movie, is euthanasia, although how that's carried out in each is quite different. In the book, one’s death is known to them instantly. In the movie, the population participates in something called Carousel with the false hope of possibly being reborn. The other difference? In the book, your final day is your 21st birthday. In the movie, it's your 30th.

In the futuristic society of LOGAN'S RUN, people live out their lives in domed cities never worrying, never struggling, never aging. Babies are assigned by name and number to their lifelong career. No one questions what they do, and everyone accepts that at the age of 30, a small light embedded in your palm begins to blink red. When that happens, it's time to go put on your white and red flaming anatomy jumpsuit, float up to the ceiling like Charlie Bucket high on Fizzy Lifting drink then hope like hell you get renewed. What actually happens is you get blown up and the population is kept in check.

Except, of course, for those few who don't accept it. They're called Runners because, let's be blunt here, they're not idiots. They know Carousel is a one-way street and they're going to do everything in their power to take a detour. Once someone runs, Sandmen jump into action. Those are the security guards of the domed cities who make sure if you run, you die. And since Runners have already figured out they're going to die anyway, why not go for the brass ring one last time?

Enter Logan, a Sandman. Logan (Michael York) isn't just any Sandman, though. He genuinely wonders why people run. Maybe it's not so crazy to live beyond 30 after all. When the computer running everything assigns him the task of posing as a Runner to find out where Sanctuary is—that's where the Runners go—Logan and his companion, Jessica (Jenny Agutter), begin to realize they've all been duped. The air outside is fine and growing old isn't nearly as awful as it's been made out to be. But that still doesn't mean he can change anyone's mind and, even if he could, attempting to do so will most likely result in his death.

That's because the other Sandman all think Logan really is running, including his friend Francis (Richard Jordan). But once they find a mad robot living in the area just outside of Sanctuary and an old man living in it (Peter Ustinov), all of their preconceptions are challenged.

LOGAN'S RUN is particularly relevant today. Sure, as a film it has a definite pre-STAR WARS hokiness to it and special effects too reliant on high-tech shopping malls and well-made but poorly lit miniatures. But as a story, it works quite well and speaks to some of the most popular doomsday scenarios facing us today. When AVENGERS: INFINITY WAR (2018) was released, in was following in the footsteps of LOGAN'S RUN. After all, Thanos is concerned with overpopulation as well, it's just that he goes with "kill half of everyone" over "only let people live until 30." Nonetheless, the two dubious solutions are brothers in arms and both strike a primordial chord, not just that concerned with survival, but with living itself.

The frightening thing about being told you can't live past 30 becomes immediately evident to you once you hit 31. Life continues and, surprisingly, you get wiser and more settled into the rhythms of life that keep you from the kind of existential panic a younger you might face. No one wants to be told they have to end all the learning, all the living and all the fun, just to make things better for everyone else because, deep inside, we know that's a bunch of hooey. If everyone can't live how they want to live, no one is better off.

LOGAN'S RUN gets that. The movie and book approach the story in vastly different ways, and I'd love to see a movie get made that follows the book's story, but until then the 1976 classic is a pretty good start. The costumes, settings, effects and music are all deeply entrenched in a ’70s sensibility which usually earns it the dreaded "dated" label from far too many people. The fact is, science fiction is of its time and in 1976 dealing with overpopulation issues was front and center. LOGAN'S RUN was about that, but it's also about depleting resources and how to handle that. And its villain is far more compelling than Thanos, the mighty Titan who wants to snap his fingers and kill off half the universe. That's because the villain isn't the computer running everything, it's the population itself. A population of people who have, for decades, willingly gone along, questioned nothing and lost their lives as a result. The enemy in LOGAN'S RUN isn't age, it's us. But like a lot of science fiction, it assures us that in the end, we can do better.

197 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lady in the Lake POV by Greg Ferrara

In 1946, Robert Montgomery had an itch to direct, an itch that nags at many an actor until they can satisfactorily scratch it. Sometimes they go on to an illustrious career directing (Clint Eastwood), and sometimes they do one masterpiece and call it quits (Charles Laughton). In Montgomery's case, it was neither. He directed six movies over the course of a decade or so, but none of them matched his debut, LADY IN THE LAKE, based on the novel by Raymond Chandler. Released in early 1947, the movie became primarily known for being shot from a first-person point of view (POV), in which we see everything through Phillip Marlowe's (Robert Montgomery) eyes. This is achieved by having all of the actors speak directly to the camera and, occasionally, Montgomery passes in front of a mirror so we won't forget he's playing Marlowe.

That this technique had failed before (in fact, Orson Welles wanted to make an adaptation of THE HEART OF DARKNESS this way but never could get it to work) didn't stop Montgomery but it did impact the film's box office and reputation. And it was an undeserved reputation, one that alleged the film was difficult to watch and the acting a little too much on the arch side of the street.

The acting critique is understandable. Since we are seeing everything through the camera, there is necessarily no cutting between points of view. We get no over the shoulder shots, back and forth, as two characters converse. We see only the actor talking to Marlowe in one long unbroken shot. That meant any take where an actor flubbed their line meant a lot of film wasted and a lot of long reshoots. The result is that unless someone screws up big, no one's going to call for a retake, no matter how overacted the scene is. This same problem is clearly evident in Alfred Hitchcock's ROPE (‘48) from just a year later. But it's really not a problem at all. In fact, I think it's pretty admirable that the actors do as well as they do and one in particular, Audrey Totter, carries the whole damn movie on her shoulders. She gives a big performance, in all caps, and damned if it isn't captivating every second of the way.

But the critique that's lasted the longest was that it was difficult to watch and it's the most dated critique of all. Since the emergence of first-person adventure games in the ‘90s, an entire generation has come of age interacting with stories by looking at characters talking directly to them on a tv, computer or phone screen. Being told that this made it difficult to play would seem alien to them. And, spoiler, I'm one of those guys.

I spent the ‘90s and early 2000s totally immersed in the world of first-person adventure games, many of which in the early years were actually done on film. I became accustomed to mysteries being played out by "walking up" to another character, having them turn to face me and then interacting with them as they talked "directly to the camera," i.e. me. And in most of those games, you don't even get a look at yourself in the mirror, like Marlowe does here. So when I came to LADY IN THE LAKE for the first time in the 2000s, after years of putting it off, I felt immediately comfortable with its first person perspective. Indeed, it seemed ahead of its time.

I've watched it again a few times since and it's become one of my favorite movies. Montgomery does a surprisingly good job as Marlowe, though being Robert Montgomery, he does seem a little too classy at times despite his best efforts to harden his edges. But as I said before, it's Audrey Totter's movie. Not only does she carry it, she makes you want to watch every movie from a first-person perspective with her talking to you.

LADY IN THE LAKE is a movie experience not to be passed up and if you're at all familiar with gaming from the last 30 years, it won't seem strange to you. The only thing strange will be the critiques you've heard that it doesn't work. It does, splendidly. And it holds a rightful claim to being the first computer first-person adventure game, before they even existed.

#Lady in the Lake#Robert Montgomery#Raymond Chandler#Audrey Totter#Lloyd Nolan#Leon Ames#Tom Tully#Greg Ferarra

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Carnival of Animal Movies by Greg Ferarra

Animals have been a part of the movies practically since the movies began. In fact, if you count Sallie Gardner, the horse used in Eadweard Muybridge's Horse in Motion, from 1878, you could reasonably claim animals were an important part of the movies before film even got started. But by the sound era, animals weren't just a part of the movies, they were stars in their own right. Rin Tin Tin and Lassie are just two examples of animal stars that topped the box office while carrying the weight of a franchise on their shaggy shoulders from fun adventures to deeply emotional dramas.

Sometimes there’s a thriller, such as DAY OF THE DOLPHIN (’73), in which George C. Scott plays a scientist who trains dolphins to communicate with humans by translating their clicks into the English language. When the dolphins disappear, it's clear someone has nefarious plans for them, but who? Based on a best seller from 1967, the movie had the unlikely director and writer team of Mike Nichols and Buck Henry. The duo previously struck success with THE GRADUATE ('67). DAY OF THE DOLPHIN works well enough and has a great score by Georges Delerue that was nominated for an Oscar.

That takes us to MIGHTY JOE YOUNG from 1949 with the same director (Ernest B. Schoedsack), producer (Merian C. Cooper), writer (Ruth Rose) and star (Robert Armstrong) of the immensely successful KING KONG ('33) from 16 years earlier. This one involves a big gorilla again, though not nearly as big as Kong, and the girl who loves him as a friend, Terry Moore. With great stop-motion animation by Willis O'Brien, it's well worth a look.

Vittorio De Sica's favorite film of his, UMBERTO D ('52), is a profoundly moving tale of a retiree, his dog and his desperate attempt to pay his rent. The film is as moving as anything ever produced and has an ending perhaps even more moving than De Sica's own BICYCLE THIEF (‘48), itself one of the most moving films ever made. For the first time viewer, the less said the better. It is, without a doubt, one of film history's must-see movies and an experience never forgotten.

Following UMBERTO D isn't an easy task but SOUNDER (’72) meets the challenge. Like UMBERTO D, this is a profoundly moving story of one family making their way without their provider when the father is thrown in jail for stealing to feed his family. Taking place in the deep South in 1933, the story centers around a family of black sharecroppers who must deal with life after the father, Paul Winfield, is sent to prison. His son, played by Kevin Hooks, tries to work the fields but also struggles to study in school. Their dog, Sounder, is shot when the father is arrested but hangs on and becomes emblematic of the resilience they all must have to survive.

Finally, there are three iconic animal movies that need no introduction: NATIONAL VELVET ('44), THE YEARLING ('46) and BORN FREE ('66). Each a classic that many children from the 1960s onward have grown up with. The Pie, Elsa the lioness and an orphaned fawn at the center of each story, respectively, have themselves become animal heroes to movie fans the world over.

34 notes

·

View notes