#Gravitational Dynamics in Cosmogony

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Circular Time in the Andean Cosmovision

This is a cosmogony that understands existence in layers. A human for instance is considered a point in time, space and consciousness. Reality as experienced it’s mostly based on the level of consciousness that the observer possesses. “Space”, through a process of a gravitational dynamic will be correspondent to the ratio of consciousness achieved. “Time” is experienced cyclically in an ever…

View On WordPress

#Andean Cosmovision Philosophy#Andean Ontology and Cosmology#Andean Spiritual Practices#Circular Time Cosmology#Consciousness and Reality#Cosmic Order and Balance#Cosmic Web of Interconnectedness#Cyclical Nature of Time#Gary Urton Andean Studies#Gravitational Dynamics in Cosmogony#Interconnectedness of Life and Nature#Marisol de la Cadena Indigenous Knowledge#Nature&039;s Reflection of Cosmic Rhythms#Non-linear Time Perception#Psychological Impact of Circular Time#Reciprocal Relationships in Nature#Rituals and Ceremonies in Andean Tradition#Shaman#shaman healer#shamanism#Spatial Dynamics in Consciousness#Spiritual Evolution and Rebirth#Time&039;s Cyclical Expansion

0 notes

Text

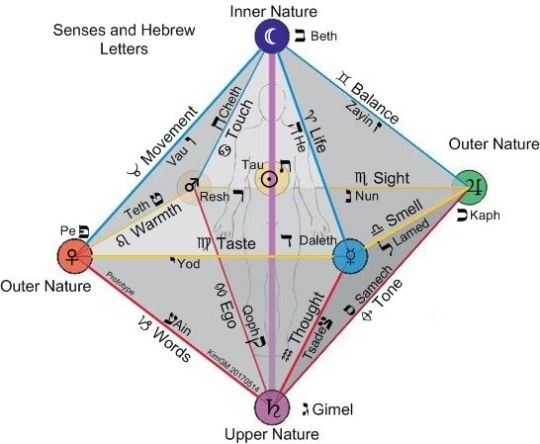

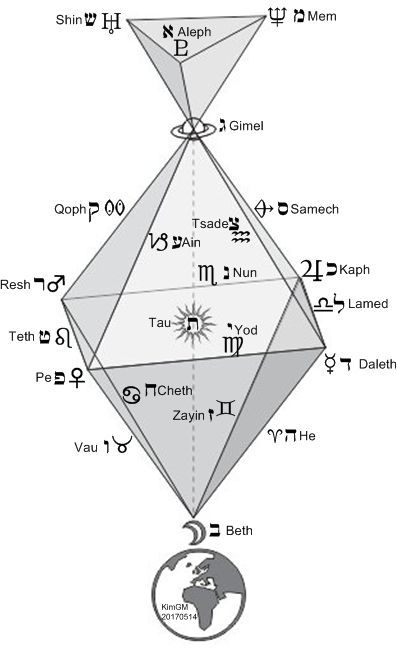

The Zodiac and Esoteric Astrology: A Short Introduction; part I.

Human beings have probably probed the cupola of the heavens in search of meaning since the birth of ego consciousness. This was a time when celestial and terrestrial events succeeded one another for reasons known only to the divine autogenerator of the cosmos, when everything deemed unconscious and inert could speak its mind, when magic was the world language, and when the fundamental cohesion of all life was an acknowledged and unspoken fact. Back then everything on the earth below was thought to mimic and imitate conditions simulated in the Great Above; the stars, planets, comets and other celestial bodies were the shining genies whose words and whispers, actions and reactions, agreements and disputations might incite minor and sometimes large-scale consequences for the lives of all corporeal inhabitants. Eclipses, conjunctions, oppositions, depressions, exaltations and other celestial events worked like knee-jerk reactions, exacting benefic or malefic influence, facilitating particular conditions, or awakening transpersonal formative forces which would work through tribal personalities. This Platonic-flavoured cosmos in which everything was Aeolian, alive and functioned through a system of meaningful correspondences entrenched itself deep in the collective psyche of human beings and has never quite relinquished its hold.

Hence, it would not be erroneous to suggest that the religious function of the human psyche first found voice in archaic astrology, a philosophy which assumes that the systematic, recurring but sometimes volatile behaviours of the celestial inhabitants mediate over all corporeal phenomena and their relationship to human life. Of course the mere fact that exact situations involving the celestial bodies in the heavens are recapitulated periodically and can be calculated with mathematical precision can only mean that the qualities, influences and relevant conditions that these events are inexplicably connected with are predictable. If, then, the path of the human condition is foreseeable through this sidereal divination then the oikoumene must, in fact, have been hewn by a conscious and creative mind that transcribed general details relating the fate of all its divine, semi-divine and mortal inhabitants, as well as its own into the plastic and intangible “ether” somewhere. Here we get a taste of the spiritual and holistic origins of archaic astrology, which, when broken down anatomically, consisted of three primary aims: to descry one’s future for a chance at changing the trajectory of fate (astrology); for meteorological purposes that included the prediction of weather (meteorology); and the transcription of stellar cycles and arrangements whose movements would have been tracked to determine an appropriate time for the inception of agricultural endeavours (astronomy).

The Chaldeans or Assyrians introduced tangible markers for the qualitative and quantitative assessment of the heavens in the second millennium bce. The star-gods, genies or divinities governed a pre-established and insurmountable destiny that vacillated between auspicious and inauspicious conditions brought on by specific stellar arrangements, and all of life on earth basically swayed or reacted to the configuration of these heavenly waters. Each was ascribed rulership over a specific day or month, forcing a dissection of time. The Chaldeans proceeded to define the band of sidereal space that encompasses the wheel of heaven and interacts with the ecliptic orbit; the equinoctial markers, embraced by the zodiacal signs of Aries and Libra, could be found at the intersection of equator and ecliptic whilst their polar opposites, the tropical or solstitial markers, were to be found in in Capricorn and Cancer. The just mentioned zodiacal signs, twelve in all, were represented zoomorphically, anthropomorphically or as composite creatures using motifs derived from Babylonian mythology, and contained an exact conformation of stars known as a constellation. With respect to each individual “sign”, the stars contained in one constellation pervaded the sidereal space taken up by the imagined zodiacal image in the night skies.

Proceeding along an analogous line of reasoning, the ancient Egyptians developed a calendrical system by observing the heliacal rising and setting of individual stars. In this arrangement the year was divided into thirty-six ten-day periods known as decans, each heralded by the heliacal rising of a particular star. The star Sothis or Sirius, a celestial embodiment of the Egyptian goddess Hathor-Isis, stood sentry over the thirty-six divisions as the inaugurator of the entire year. In the third century bce, when knowledge of oriental astrology and its esoteric philosophy of astral determinism reached Egypt through a Hellenistic dispensation enabled by Alexander the Great (356-323 bce), the zodiacal and decanal systems merged and three decans were incorporated into each zodiacal sign. A few acclaimed esotericists like René Adolphe Schwaller de Lubicz (1887 – 1961) have argued against a Chaldean importation of astral determinism into Egypt, claiming that the Egyptians were holistic thinkers and believed that each part of the human body was under the mediation of a different star-god or genie that could be invoked to heal illnesses pertaining to its respective part. Despite its innovative potential and viability, the theory is disparately related to the current discussion and will not concern us for the time being.

A little before Alexander’s conquest the holistic tradition of esoteric astrology began to differentiate into subcategories. Meteorology became a distinct branch but it wasn’t until the time of Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) that the mechanistic natural protoscience known as astronomy and the animistic qualitative cosmogony of astrology parted company. The latter matured fully during the second century ce, a period when Claudius Ptolemy (90-168 ce) penned an astrological treatise entitled the Four Books, or Tetrabiblos in Greek. It was a comprehensive volume of horoscopic astrology, a subcategory of the divinatory art that seeks to comprehend meaning and answer questions using a celestial chart or horoscope which captures an exact moment in time. The work transcribed the qualities of the astrological signs, the twelve zodiacal constellations on the wheel of heaven that subsisted through the ages and remain both meaningful and functional to this very day.

In entertaining an esoteric interpretation on the zodiac one sees that the universe is united as One but at the same time coloured by archetypal forces or elemental blueprints that originate from a mother membrane and act upon the existing spectrum of variegated consciousness. Of vital importance is the acknowledgement of the twelve established signs as functioning symbols; while our ancestors almost certainly imagined shapes and signs in cupola of the star-studded night, their choice of animals and figures , real or imagined, are not as random as some might believe. As unlikely as it seems, the ascribed zoomorphic, anthropomorphic or composite creatures exhibit qualities that correspond dynamically to the inherent nature of the group of stars in their respective corner of the heavens. To give an example the stars of Cancer are symbolically depicted by the crab; the latter habitual tendency to seek and never veer far from the comfort of its home, a trait almost universal amongst all modes of being born under its section of the sky. While individual stars may belong to a collective archetype in the manner that a group of human cells belong to one organ and work in conjunction with one another to achieve a common aim, their unique positions, magnetism and gravitational force within the astral configuration permits a degree of freedom from collective law. This is why the zodiacal band of sidereal space was sometimes depicted in an active state of unfurling like a parchment of Nile papyrus.

The name given to this precession of imagined figures that comprise real cosmic phenomenon–zoe-diac, or circle of life–is wholly appropriate given that the general archetypal patterns or transpersonal influences of being that exist manifest through all complex life irrespective of time and space and are deemed to repeat for all eternity like a broken record. The fiery, restless, urgent and explosive Martian formative force that wishes to subjugate, to divide and dissect, to compartmentalize, to create, to own, to dominate and to ascend the evolutionary ladder, for instance, is indigenous to the fixed stars of Aries. This energy seeps down into consciousness, sometimes in copious amounts and sometimes in minute quantities, depending on the trajectory of the sun’s annual circuit and its conjunction with the stars of the respective constellation. In fact the nature of the latter’s influence is determined by the conjunction of the sun with the stars of the head, of the horns, of the hindquarters, of the forepaws, and so forth. The bold head of the ram is aggression; the horns raw abundance and virility; his hindquarters signpost stamina but sometimes a gross overestimation of strength; his forepaws vulnerability and restlessness. Notwithstanding its waxing and waning powers, the Arian sign is ubiquitous and indestructible, an inhabitant of the timeless zone that subjects and bends everything to its will. This indissoluble will is why all animation is fated to endure an endless cycle of everlasting repetition...

Paul Kiritsis

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Investigating the Rainbow Body

by Michael Sheehy

If we look across spiritual traditions, we find the human body is broadly envisioned to be a vessel that contains the essence of existence and transformation — a container, likened to clothes that are to be stripped off or a boat that is to be abandoned once one has reached the breaking shore at death. Similarly, there are modern philosophical and scientific models that conceive the body to exist separately from the mind, the kind of mind/body dualism that Gilbert Ryle described as a “ghost in the machine.”

Though we find practices of bodily abandonment and denigration throughout Indian spirituality, the Vajrayana Buddhist traditions that were received and developed in Tibet — due to the synthetic collaborations of Buddhism with the arts and sciences of medicine, astrology, alchemy, and physiology that occurred during the formative period of tantra during the seventh through ninth centuries — place an emphasis on the body as a locus of transformation. Similar to Daoist traditions of alchemical transformation, there are Vajrayana traditions that say that all tangible matter consists of congealed forms of the five elements: space, air, fire, water, and earth. As described in The Tibetan Book of the Dead and illustrated in the murals of the Lukhang or so-called Secret Temple of the Fifth Dalai Lama in Lhasa, there are cosmogonies that suggest the elemental energies that make up the cosmos are undifferentiated from those that make up the human body, and as such the body is a holon, simultaneously the individual person and the cosmic whole.

In Dzogchen cosmology, the primordial space of the cosmos is envisioned as being utterly open and translucent. Due to the natural effortless play of the cosmos itself, movement ensues. With this initial gesture, however slight, the element of air stirs up wind that oscillates rapidly into fire; from fire emerges the liquidity of water, and from water the solidity of rock and earth are stabilised. With this gradual gravitational collapse into the elemental forces that comprise the cosmos, a concomitant spiralling reconfigures matter into worlds wherein embodied beings emergently form. As such, the body is conceived to be a part of the whole, seemingly fragmented from itself. Not unlike contemporary astrophysics, Vajrayana traditions view our bodies to be an evolutionary product of billions of years of bathing in bright light.

Describing the reversal of this gestation process, The Tibetan Book of the Dead details the dissolution of these five elements during the time of death. First the body becomes heavy and sags as the earth element dissolves, saliva and mucus are excreted as the water element dissolves, the eyes roll backward as the fire element dissolves, the breath becomes wheezy as the air element dissolves, and finally consciousness flashes and flickers with turbulent visions as the space element dissolves from the physical body.

According to Dzogchen tradition, under certain circumstances the cosmic evolutionary process of gravitational collapse into solidity can turn itself back into a swirling, highly radiating configuration. That is, there are Tibetan traditions that suggest that meditative technologies can intentionally reverse this process of collapse, thereby altering the gravitational field so the inherent radiance of these condensed elements blossom. When this happens, the five elements of the body transform into the five lights of the colour spectrum. The Tibetan name given to this fluorescence is jalu, literally translated as “rainbow body.”

Material bodies dissolving into light is the subject of Rainbow Body and Resurrection by Father Francis V. Tiso, a priest of the Diocese of Isernia–Venafro who holds a PhD in Tibetan Buddhism. Exploring the body as a vehicle of spiritual transformation, this book presents Father Tiso’s research on postmortem accounts of the rainbow body of Khenpo A Chö (1918–98) in eastern Tibet, historical background on Dzogchen and early Christianity, and a comparative discussion of the rainbow body and the mystical body of Christ.

Father Tiso introduces his work by acknowledging that because research on postmortem paranormal phenomena cannot be conducted in a laboratory, there are inherent tensions that exist in conducting scientific investigations while relying on the good word of faithful informants. Seeking to take the approach of a participant observer in the tradition of anthropology, Tiso’s chapter on Khenpo A Chö is largely a series of journal logs from fieldwork in eastern Tibet and India and transcripts from interviews with local eyewitnesses.

What is missing at the beginning of the book is an overview about rainbow body phenomena in Tibet. In addition to references to pre-modern episodes found in Tibetan literature, such as mentions of Padmasambhava’s consort Yeshe Tsogyal going rainbow, reports of rainbow bodies have been emerging from Tibet sporadically over the past century. Perhaps the best known among English-reading Buddhists is that of Yilungpa Sonam Namgyel, who went rainbow in 1952, as recounted by the late Chögyam Trungpa in his memoir, Born in Tibet. There is also the case of Changchub Dorje (1826–1961?), a medical doctor and leader of a Dzogchen community in the Nyarong region of eastern Tibet, about whom we have stories from his living disciples, including Lama Wangdor, and from Chögyal Namkhai Norbu’s The Crystal and the Way of Light. Other well-known cases include: Nyala Pema Dudul (1816–1872), whose life story was written about by the great Nyingma master Mipham Gyatso (1846–1912); the Bonpo meditation master Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen (1859-1935); Lingstsang Dzapa Tashi Odzer; and Khenchen Tsewang Rigzin (1883–1958). Also within the past few years there have been several reports such as those of Lama Achuk (1927–2011), Khenpo Tubten Sherab (1930–2015), and most recently, the mother of Lokgar Rinpoche. What is striking about many of these exceptional figures, including Changchub Dorje and Khenpo Tubten Sherab, is that they tended to be unflashy and nonchalant about their meditative accomplishments. In fact, there are numerous stories in Tibet of inconspicuous nomads and illiterate common folk who shocked their communities by going rainbow.

One particularly fascinating social dynamic that has emerged since the Cultural Revolution — and this has affected the reporting of numerous cases — is that the Chinese government has declared going rainbow to be illegal. In effect, because the phenomena so dramatically challenge the normative paradigm, there has essentially become a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy about masters going rainbow in Tibet. For instance, Changchub Dorje’s shrunken bodily remains were hidden from authorities for years until the proper ceremonies could be openly performed.

So what exactly does rainbow body look like? According to these traditions, there are signs that indicate an adept has stabilised meditative realisation of the mind’s innate basic radiance. While alive, it is said that the bodies of these beings do not cast a shadow in either lamplight or sunlight; at death, signs include their physical bodies dramatically shrinking in size, and their corpses exuding fragrances and perfumes rather than the odours of decomposition. A common Tibetan metric for the shrunken corpse of a body gone rainbow is the “length of a forearm.” In the case of Khenpo A Chö, as Father Tiso notes, the local Chinese press reported that his body “shrank to the size of a bean on the eighth day and disappeared on the tenth day. What remain are hair and nails.” Other signs are the sudden blooming of exotic plants and flowers anytime of year and, of course, rainbows appearing in the sky.

These signs mark someone who has attained rainbow body, and some are said to have occurred in each of the cases mentioned above. However, there is also a special kind of rainbow body known as the great transference into rainbow body, or jalu powa chemo. This is the complete transference of the material body into radiance so that the only residue of the body is hair and fingernails. Great transference is a deathless state. Realised by Dzogchen meditation masters such as Garab Dorje and Padmasambhava, the great transference rainbow body is understood to be the actual enlightened qualities of these realised masters. Not unlike Christian saints, these qualities are understood to be continually available for beings to receive through the reception of light.

While it is tempting to draw parallels between the luminous bodies of Dzogchen meditation masters and saints, or even with the risen mystical body of Christ, Father Tiso goes one step further. Discussing the exchange of religious ideas along the Silk Route, and possible historical influences of Syriac Christianity and Manichaeism in the pre-Buddhist civilisation of Tibet, he asks if the first human teacher of Dzogchen, Garab Dorje, could have been a Christian master imported from the Middle East — or even the messiah himself.

The strength of Father Tiso’s book is its tremendous and ambitious breadth. He brings to the reader’s attention a broad spectrum of doctrinal and historical information not only about what he refers to as the “Church of the East” and possible doctrinal influences of Christian light mysticism on Tibetan religion but also about early Dzogchen practice. Discussing encounters of Christianity with Buddhism and Daoism, he cites little-known Christian mystics, including the Desert Fathers of Egypt, Evagrius, Abraham of Kashkar (ca 501–586), and John of Dalyatha (ca 690–786), all of whom he argues were critical figures in spreading the “religion of light.”

One example of this cross-fertilisation with which Father Tiso tantalises us is the Jesus Sutras, seventh-century Christian texts that were preserved among the caches of manuscripts discovered in the Central Asian cave complexes at Dunhuang. Thought to be have been produced by the Church of the East and Syro–Oriental Christian communities who travelled along the Silk Route, these texts remarkably borrow literary forms and devices employed in Buddhist sutra literature while echoing doctrinal claims of Christian theology in typical Buddhist parlance. For instance, similar in arrangement to many Mahayana Buddhist sutras, these texts present a question-and-answer dialogue about topics of spiritual self-cultivation, except instead of speaking with the Buddha, the interlocutor is the Messiah Christ.

Am I convinced that a Church of the East influenced Dzogchen in Tibet? Was Garab Dorje actually Jesus Christ? Did Christian light mysticism have a significant historical impact on the formation of yogic technologies that culminated in Tibetan expressions of rainbow body? These are certainly alluring questions. However, that’s not entirely the point. Father Tiso makes a compelling case by bringing his reader an intercultural, cross-historical, and inter religious discussion of the esoteric arts. To what extent there was bona fide synthesis among these meditative traditions from Egypt and Syria to China and Tibet is a discussion that warrants more attention and that this book propels forward. What’s most important, however, is that this work brings attention to the shared human experiment of contemplative transformation.

#bodhi#bodhicitta#Bodhisattva#buddha#buddhism#buddhist#compassion#dhamma#dharma#enlightenment#guru#khenpo#Lama#mahasiddha#Mahayana#mindfulness#monastery#monastics#monks#path#quotes#Rinpoche#sayings#spiritual#teachings#tibet#Tibetan#tulku#vajrayana#venerable

10 notes

·

View notes