#George Douglas Master of Angus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On August 16th 1540 Sir James Hamilton of Finnart was executed.

If ever there was a fall from grace this is it, Hamilton was an architect and noble, known as the ‘Bastard of Arran, back in the day Bastard was not classed as a swear word, it merely meant being illegitimate, in this case he the son of James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran. Knighted aged around 17 and seems to have been well thought of, at least by his peers.

If you have visited some of the castles and palaces of Scotland you will have seen Hamilton’s’ work, he is credited with much f the Palace at Falkland you see today, and the Palace at Stirling Castle. He also built Craignethan Castle in South Lanarkshire for himself after being gifted the Craignethan Castle by King James V.

Hamilton was also involved in intrigue and persecution; he murdered John Stuart, the Earl of Lennox, and participated in the oppression of the Protestants, including his own cousin Patrick Hamilton, who was burnt at the stake in 1528. Known for his temper, Hamilton also provoked the infamous 'Clear the Causeway’ skirmish in Edinburgh.

Also called Cleanse the Causeway, the Skirmish was the result of enmity between the House of Hamilton and the “Red” Angus line of the House of Clan Douglas, both powerful noble families jealous of each other’s influence over King James V. The fight went badly for the Hamiltons, and Sir Patrick Hamilton and about 70 others were killed in the incident. The Earl of Arran and Sir James fought their way out, and escaped along a narrow close. Stealing a nearby pack-horse that had come into the city with coals, they fled through the shallows of the Nor Loch marshes.

Having survived this he seems to have still been in a good position of influence in the Royal Court and held the post of Lord Steward of the Royal Household and Master of Works.

For unexplained reasons his fickle King became convinced that Hamilton was plotting against him and, despite there being no evidence to support this, arrested his old friend, some of the evidence the King offered on August 16th 1540 at the trial was from 12 years previous and reads;

“Sir James Hamilton of Finnart, having been convicted of the treasonable shooting of guns and firing of missiles outside the palace of Linlithgow and from the bell-tower of the same, at the king and the people in his company, both at the time the king came to the palace and when he withdrew from the same, and especially at his lodging place in the same town, the king being personally present at the time of the firing of the said missiles. And for art and part in the treasonable imagination, planning, and consultation, vulgarly called devising, of assassinations, at the time it is said he was with Archibald Douglas of Kilspindie and James Douglas of Parkhead at the chapel of St Leonard near Edinburgh, after the forfeiture of Archibald Douglas, formerly Earl of Angus, George Douglas of Pittendreich his brother, and the said Archibald Douglas, his father, and also during the siege of Tantallon Castle in consultation with the said Douglases, how he would enter by the window near the upper part of the bed, 'the bedhead’ (superiorem thori - literally above the pillows), in the King’s palace near Holyrood Abbey, and how there he would commit the slaughter of the King. And for common treason and conspiracy against the King, his realm and lieges. Therefore it was given that this James forfeited his life, lands, rents and possessions to the king as his escheat, to remain with him in perpetuity.”

That is how it read from the record books, they weren’t keen on paragraphs back then!

After losing his head in Edinburgh King James seized his lands, taking the silverwork from the chapel at Craignethan along with a chest of the families paperwork many of which were destroyed by crown officers. Cardinal Beaton gave money to his widow, as she was his relative.

That wasn’t the last the King heard from The Bastard of Arran though, Finnart is said to have appeared to the James V in a dream, and declared that he “would shortly lose both arms, then his head.” This prophecy came true, as the King lost both of his young sons in 1541, and died himself in 1542. The story was recorded by John Knox and George Buchanan.

Wiilliam of Hawthornden and George Buchanan both cited the execution as evidence of arbitrary cruelty and greed in the behaviour of James V, I've said it before that the Stewarts were a ruthless lot. The reasons for Finnart’s execution remain unclear and are still debated between some historians to this day.

Pics are of Linlithgow Palace and Craignethan Castle.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

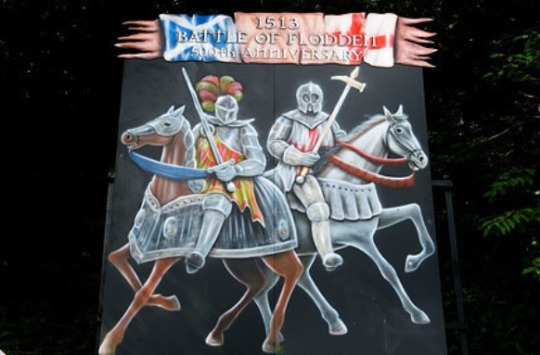

2.02 FLODDEN

Just gonna pop in here because I've seen people wondering if it was Catherine who murked King James at the battle of Flodden. I was rewatching it this morning and it looks like it was actually George Douglas, (father of Angus Douglas) - who also died at the Battle of Flodden.

If you watch the scene more closely, James is killed on the field almost instantly after George Douglas (probably where the confusion came from). Not that I would put it past TSP to have Catherine pull the trigger.

#The Spanish Princess#The Battle of Flodden#tsp 202#George Douglas Master of Angus#James IV of Scotland#tsp season 2

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supreme Court

The Warren Court (1953 - 1969) is largely considered the most liberal court in American history, with William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan, Earl Warren himself (the only liberal Chief Justice I think America has ever had), and very briefly Thurgood Marshall. Hugo Black started out super liberal, but became politically neutral as the years went on:

The Burger Court (1969 - 1986) was technically liberal, but acted as a transition between the truly liberal Warren Court and the super conservative Rehnquist Court. It contained William O. Douglas, the second most liberal justice behind Louis Brandeis, AND William Rehnquist, the second most conservative justice behind Clarence Thomas:

The Rehnquist Court (1986 - 2005) was one of the most damaging things Ronald Reagan ever did to this country, and that's saying something because he destroyed the middle class, killed hundreds of thousands of people, and sold the government to billionaires who can buy and sell whatever legislature they want. Reagan took the most conservative justice on the court and made him the chief, when the chief is generally supposed to be politically neutral so as to maintain an air of independence and impartiality; Reagan said fuck this, I want the court to be unquestionably conservative. His appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor at the end of the Burger Court single-handedly allowed the Republicans to maintain the chief justiceship into the 21st century; O'Connor was the median justice, a swing vote, and had she voted differently in Bush v. Gore, Al Gore would have become president and he would have gotten to replace Rehnquist in 2005 instead of George W. Bush. The Rehnquist Court also saw the most egregious, unconscionable, toxically partisan shift in the court's history, replacing the super liberal Thurgood Marshall, the first black justice, master orator, voice of the civil rights era, with Clarence fucking Thomas, a race traitor famously known for playing devil's advocate ("if this, then why not this? Why not further? Why not even worse?") That was a sick joke, replacing a black liberal justice with a black conservative justice. Fuck George H.W. Bush for that and many other reasons (he accidentally gave the liberals Souter though; he didn't bother vetting him, he just put him on the court and hoped he would be conservative, but he ended up being super liberal):

The Roberts Court (2005 - present) is an absolute mess. While previous courts had peaks and valleys, they tended to stay close to the center on average, whereas the Roberts Court is like a scatter gun going in either direction. Conservatives get more conservative, liberals get more liberal (though not nearly as fast; Obama replaced the liberal John Paul Stevens with a more moderate Elena Kagan who has actually stayed the same since her appointment). Republicans really liked the Marshall-Thomas shift, and they replayed it in 2020 by replacing the liberal Ginsburg with the conservative Barrett. Take a super competent woman and replace her with a stooge bought and paid for by partisan lobbyists; SICK FUCKING JOKE. I don't know enough about Neil Gorsuch, but Barret's appointment made Brett fucking Kavanaugh the median justice. Brett "I Really Like Beer" Kavanaugh, the guy who said it wasn't sexual assault because it was at a party and everybody was doing it but it also didn't happen, THAT guy. He is now the center of the court. He's not gonna be a swing justice like O'Connor of Kennedy. Kennedy was bribed to retire specifically to put Kavanaugh on the court, and his debts mysteriously vanished the second he was sworn in; I pray Merrick Garland investigates this. I would like nothing more than to see Trump's justices go down in flames and resign in shame.

This is just sad. The Democrats' best chance at maintaining their 6-3 minority will be for Breyer to retire (preferably this year), so Biden can put a younger liberal on the court, though I expect a senator like Joe Manchin to dig in his heels and say he'll only vote for neutral candidates. He doesn't give a shit about neutrality, he voted for Gorsuch AND Kavanaugh, and only voted against Barrett because he didn't want to be seen as a hypocrite during an election year; he would have confirmed her if it has happened in 2019. Democrats need to expand their senate majority in 2022 so they don't NEED Manchin anymore; once he's out of power, I'm sure he'll become an independent and caucus with the Republicans, much the way Jim Jeffords did with the Democrats in 2001. Jim Jeffords, Bernie Sanders, Angus King, all the independents this century have been liberal so far; I think a conservative independent is coming very soon, though I expected it to come from Alaska, not West Virginia. Who knows, I may be wrong.

Thomas has probably still got a good 15 or 20 years in him before he dies, and he WILL die before he retires. The only way he would ever resign is if a super conservative Republican is in office when he's 90. He won't make the mistake Ginsburg made and hope he'll last until his party is back in power, he'll retire then and only then to ensure conservative continuity. Once Breyer retires and Thomas dies, it will leave Alito and Roberts as the longest serving justices; Roberts may become the swing vote again, though not for a long time. He'll never dip into the liberal side, but I expect he'll at least pretend to be politically neutral to avoid looking culpable should a civil war eventually breaks out. "No, don't execute me by firing squad, I was trying to keep things independent!" Scalia, Alito, Thomas and Kennedy all became more conservative under Obama (gee, I wonder why?), so I can only expect Trump's Three Stooges to shift rightward too now that Biden is in charge.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forensic Incoherence - TSP Edition

Ok I snapped and thought I’d get it out of my system. Also because I’m petty and I let things annoy me more than they should. I’d like to say first and foremost that people can and should still enjoy ‘The Spanish Princess’ as a fun tv show if they like, I’m simply pointing out that when it comes to Scotland, it bears even less resemblance to actual history than usual.

Also it is by no means the worst representation of Scotland! Which is saying something because it is NOT good. It’s about par for the course I’d say, with regards to the way mediaeval and early modern Scotland are portrayed in the media. Outlaw King and Outlander rise slightly above the mark but only just- i.e. they’re somewhat good pieces of historical media that are still inaccurate but are recognisably Scotland (and have some nice panning shots and good soundtracks). The middle point is probably inaccurate MQOS movies because they’re the least painful kind of inaccuracy that’s still kind of bad (but even their soundtracks don’t save them- I’m sorry John Barry). I will not say what the absolute worst piece of media is, I believe I have yet to encounter it and for that I am grateful. TSP is somewhere between the worst and the middle. The point is, most historical media about sixteenth century Scotland generally sucks, and this tv series is about the usual kind of bad. So I wouldn’t be so irritated with the people who made it if it weren’t for one or two individuals’ saying things about how ‘it really happened’.

With that in mind this is a good teachable moment. Usually there’s little point to a detailed analysis of where inaccuracy occurs in a tv show or movie- let’s face it, if they weren’t all a bit inaccurate they probably wouldn’t work too well on screen. However in this case it is such a classic example of the usual, standard depiction of Scottish history that it provides a great resource for showing where these things go wrong (which is everywhere).

So I thought I’d strip back a reasonably mediocre, not too terrible, not overly interesting piece and ask what we have left of sixteenth century Scotland after we’re finished.

I should point out I did not watch the first series of this show, and am basing this solely on the representation of the actual country in the first episode of season 2.

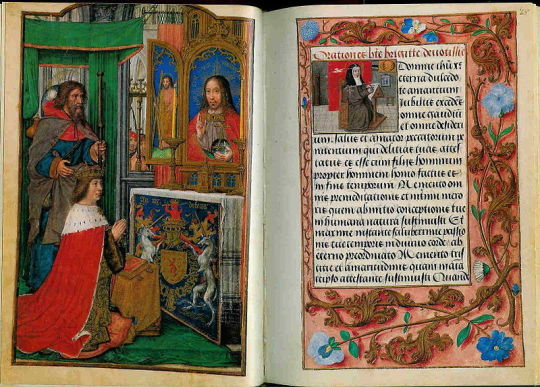

(Hours of James IV, source- wikimedia commons)

Now I’ve talked about James IV’s children in the first of the three scenes involving Scotland already. The last scene doesn’t have much meat in it except that I can confirm Margaret Tudor did lose multiple children and it WAS sad. So that leaves us with the second scene- the so-called ‘council’.

We open on your Usual Nonsense. Lots of men, many wearing tartan, with two famous surnames thrown in there for fun, arguing because The Clans Are Fighting Again.

I don’t have room to go into a whole analysis of the clan system and why our 21st century concept of ‘Highland clanship’ is not really applicable to many of the families at the centre of sixteenth century politics. Safe to say it is especially not applicable to the Red or Angus line of the Douglases (because yeah there were multiple different branches of that famous family), and only applicable to some of the branches of the Stewart family (and there were dozens of them, spread all over the country and operating in very different cultural worlds).

If Scottish politics worked the way that these writers seem to think it does- i.e. you support everyone who shares your family name against all others- then one wonders why James IV hasn’t taken the side of the Stewarts, seeing as that was his surname. Surnames and blood feud were very important in Scotland, both to traditional “clans” and to other families to don’t fit that bill, but they’re not everything. T.C. Smout famously said that “Highland society was based on kinship modified by feudalism, Lowland society on feudalism tempered by kinship.” Not everyone would agree wholly with that statement, but it’s a good starting point for beginners. Nonetheless, at no point should that confirm anyone’s belief that Scottish politics consisted basically of a bunch of clans with their own unique tartans and modern kilts running around the hills killing each other.

It’s also quite funny since James IV’s reign was one of the most (comparatively) peaceful in Scottish history between the Wars of Independence and the Union of the Crowns. He also had very little trouble controlling most of his subjects when it really mattered.

But I digress. We have Clans TM. They are Arguing. There are Douglases. There are Stewarts. It’s about as complicated as an Old Firm game, but less intellectual. This is supposed to be a serious political council.

(read more below)

Firstly, I can’t seem to find a good concise source, but based on a brief flip through the various charters, council decisions, accounts, and secondary sources on James IV’s reign I don’t think there were even any Douglases on the privy council in early 1511. Not that it’s a huge issue in itself- I don’t think that period dramas really put that much thought into representing the bewildering government reshuffles and that’s not really their main purpose anyway.

But what it leaves is this motley collection of characters, some of whom have historical figures’ names, and others who have vaguely plausible names that can’t be assigned to a specific person, and others who are unnamed set dressing but I get the feeling have probably been discreetly named something like Big Chief Hamish McTavish.

So among the few named characters you have George, Gavin, and “Angus” Douglas. These three are all presumably based on historical figures and it’s not too difficult to identify them, even if (like James IV’s children in another scene) they probably shouldn’t have been in the room.

“Angus” is presumably supposed to be Archibald Douglas, Margaret Tudor’s second husband, who became 6th Earl of Angus in 1513 (so two and a half years after this scene is set). “Angus Douglas” is not his name, in any way. It would be like me referring to Henry VIII as King England Tudor. Bit of a ridiculous mistake to make, if IMDB is not lying to me, since it implies that not only did the scriptwriters not even bother to use google, they didn’t even read the (somewhat inaccurate) novel that they based their show off.

Angus is not a common first name in the Douglas family during this period. In fact I don’t think I have ever heard of anyone called Angus Douglas from the sixteenth century or earlier. It was popular in some families from the west and the far north- mostly Gaelic-speaking families like the MacDonalds and the Mackays- but not really among the inhabitants of the Borders and Lowland east coast, which is where the Red Douglases held *most* (though not all) of their power. The earls of Angus took their title from a region in the east/north-east of the country, but they had a large power-base in the Borders and East Lothian too (not least the hulking red sandstone castle of Tantallon on the Berwickshire cliffs).

(The highlighted region is the modern version of Angus, between Dundee and Aberdeenshire. Nowadays, it has red-brown soil, old Pictish monuments, it grows wonderful raspberries and strawberries, and its main towns include Montrose, Arbroath (with its red sandstone abbey), Brechin, and Forfar. The urban and agricultural make-up would have been different in the sixteenth century though. The Borders meanwhile are pretty self-explanatory).

In 1511, Archibald’s grandfather, also Archibald, was still alive and held the title Earl of Angus. His eldest son George, Master of Angus (the younger Archibald’s father) was his heir apparent in 1511. Now the elderly 5th earl was still a wily character but he was old, and had also been held in custody on royal orders on the Isle of Bute until as recently as 1509, because the 5th earl and James IV had... well it was a complex relationship. We could perhaps assume that he was not able to travel easily- hence why his eldest son George, Master of Angus, seems to be the ‘George’ who is represented in that council scene. Somehow, I don’t see Archibald Junior being called his own grandfather’s title rather than his name when his father was in the room. George, Master of Angus, died at Flodden, which is why he did not succeed to his father’s earldom and the claim passed to his eldest son Archibald.

(There was another George Douglas worth mentioning, though he wouldn’t be in this scene- George Douglas of Pittendreich, Archibald’s younger- and, let’s be honest, smarter- brother. He was father to the Regent Morton).

The last is Gavin Douglas- probably the most interesting of the three to any literary scholars. He was the younger brother of the Master of Angus, and thus uncle to Archibald. He is one of the most important Scots poets- or makars- of James IV’s reign, and personally I would only place him beneath the great William Dunbar (the other big contenders, Henryson and Lindsay, respectively wrote most of their works before and after the adult reign of James IV). His works include the “Palice of Honour,” “King Hart”, and his greatest achievement the “Eneados”, completed c. 1513, which was the first full vernacular translation of the Roman poet Virgil’s Aeneid in either English or Scots. After Flodden, he became Bishop of Dunkeld, partly through Margaret Tudor’s influence, and didn’t find much time for writing any more poetry in the reign of James V, being consumed by political struggle. He died in exile in England in 1522.

Sixteenth century Scots had many complex and conflicting emotions and opinions, and one could severely hate and distrust England while remaining friends with certain Englishmen or respecting certain English customs. Nonetheless I find it a bit funny that Gavin Douglas is the one who is given the line ‘the English are the root of all our troubles’ since there was one thing that the English gave the world that no early sixteenth century Scots makar worth his salt could ever forget- and that was Geoffrey Chaucer (as well as his compatriots Lydgate and Gower). In his ‘Eneados’, Gavin Douglas himself described the great poet as “venerable Chaucer, principall poet but peir”. Which is not to say that such a character could not also have raged against the English on more than one occasion, this is merely to demonstrate that these three named men were rather more complex than the simplistic kilt-wearing, knife-wielding, drunk, Anglophobic, entirely uncultured stereotype we have on screen.

(And while I’m on the kilt and tartan thing- I literally JUST said that the Red Douglases were mostly centred on the Lowlands, and in particular the Borders. While it’s not impossible that they could have occasionally worn tartan, it’s not exactly everyday dress for them- unless you think it was also day dress for people in Carlisle as well. I notice Archibald Douglas himself isn’t really wearing any- perhaps this is to make him look more palatable. And don’t even get me started on the whole “the clans are fighting” thing).

(Look here’s a nice picture of Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus- admittedly when he was a bit older and had been in exile in England, but look! He’s dressed like other people in sixteenth century Europe! Nothing wrong with tartan but not your usual sixteenth century Borders earl gear.)

Funny thing is though, while the earls of Angus were undoubtedly important (and Gavin Douglas, being a university man, could act as an official), they’d lost their influence a bit by the end of the reign (again, the 5th Earl and James IV had a very layered relationship). Now, while lists of witnesses to charters do not necessarily reveal everything, if you were looking for powerful men who are likely to have been at the centre of government and on the king’s council in 1511 (and not just noblemen who were friends with the king but didn’t have government posts) I would look for some of the below first:

- Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St Andrews and Chancellor of Scotland in 1511. He appears at the head of the witness list in almost every charter in the first half of 1511, and also signed off on the royal accounts. A young man, only about eighteen in 1511, who had studied under Patrick Paniter (see below), and then later had travelled on the continent and studies under humanists like Raphael Regius and Desiderius Erasmus. He was also James IV’s eldest son, though illegitimate- however although his promotion was undoubtedly nepotistic, there are signs that he would have made a pretty competent archbishop and he certainly actually did his job as chancellor. Although an archbishop (but never old enough to be fully consecrated or receive the revenues of his see), he followed his father to Flodden and died in battle. Erasmus famously eulogized him in his ‘Adages’, saying that:

“when a youth scarcely more than eighteen years old, his achievements in every department of learning were such as you would rightly admire in a grown man. Nor was it the case with him, as it is with so many others, that he had a natural gift for learning but was less disposed to good behaviour. He was shy by nature, but it was a shyness in which you could detect remarkable good sense.”

(A sketch from the Recueil d’Arras which is allegedly a copy of a painting of Alexander Stewart)

- William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen and Keeper of the Privy Seal in 1511. A man with many years of experience at the centre of government. After studying at Glasgow, Paris, and Orleans, he was made bishop of Ross and travelled to abroad on diplomatic missions. He had previously been High Chancellor of Scotland under James III, and even though he spent a small part of James IV’s early reign out in the cold he was soon brought back into the fold and played a leading role in government. Even though he was never chancellor again, he held the privy seal until the end of his career and often acted as de facto chancellor during the tenure of James IV’s younger brother the Duke of Ross (also an earlier Archbishop of St Andrews). William Elphinstone is also remembered for being a very active bishop in his diocese- he built a bridge over the River Dee, rebuilt part of the cathedral, and founded the University of Aberdeen, which received its papal bull in 1495. He organised the construction of King’s College, and the chapel built on his orders is still at the centre of the university’s campus today. He also sponsored the publication of the Aberdeen Breviary, on Scotland’s first printing press. He is supposed to have been against the invasion of England in 1513, but after the king’s death, Elphinstone was seen as the natural choice to succeed Alexander Stewart in the archdiocese of St Andrews, despite his age. He died in late 1514.

Andrew Stewart, Bishop of Caithness, Treasurer in 1511 takes third place on a lot of charters. Less can be said about him than the first two, though his rise at the centre of government really took off around 1509. He was Treasurer in 1511. It is not clear which branch of the Stewarts he hailed from, but it may have been the Stewarts of Lorne, which would have made him a distant cousin of the king and a slightly closer cousin of the king’s last known mistress, Agnes Stewart. Things are not made any simpler by the fact that, after his death, the next bishop of Caithness was ALSO called Andrew Stewart, and this one was an older half-brother of the Duke of Albany and a son of James IV’s uncle. The main takeaway- there are lots of Stewarts in Scotland, including the Royal Stewarts, and too many branches of the family for any simplistic tale of “clan” rivalry with the Red Douglases to be at all compelling or make sense. It is also worth noting that until 1469, Caithness would have been the most northerly diocese in the kingdom- whether Andrew spent more time there or at the centre of government is unclear.

(A rare contemporary painting of William Elphinstone, bishop of Aberdeen and Keeper of the Privy Seal)

Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll and Master of the Household in 1511- This post was less explicitly a ‘government’ post but the royal household still had an important political role. Even without this government post, though, the earl of Argyll was an important man. One of the two ‘new’ earldoms created in the reign of James II, the earls of Argyll were sometimes seen as royal ‘policemen’ in the West Highlands and islands. Their earldom was named after the large region on the west coast of the same name, cut up by sea-lochs and mountains. However they often had their own agenda and could exercise some independent policies in the Isles and northern Ireland. The earls of Argyll were usually the chiefs of Clan Campbell (look! An actual Highland clan for once!), including its many cadet branches. Clan Campbell has a very black reputation now (with some justification), though it is worth mentioning that in the sixteenth century they were also patrons of Gaelic culture and poetry, and frequently intermarried with the families they were meant to be ‘policing’. Notably, Archibald’s sister had been married to Angus Og (MacDonald), son (and supplanter) of the last “official” Lord of the Isles, but after Angus Og’s murder in the 1490s, the then earl of Argyll kept Angus’ son (his own grandson) Domnall in custody on behalf of the Crown- at least until he escaped and started causing all kinds of trouble in the early 1500s. Archibald Campbell, also called Gillespie, was the second earl of Argyll and rather less influential than his father had been, but he was still one of the most important laymen involved in government in the latter part of James IV’s reign. He died at Flodden in 1513.

Matthew Stewart, 2nd Earl of Lennox and Lord Darnley- Appears as a witness in many charters and is mentioned at council meetings on occasion. Yet another branch of the Stewart family- I must reiterate, a shared surname, though important, did not necessarily mean that everyone shared the same rivalries or stuck together through thick and thin. The Lennox is a region at the south-western edge of the Highlands, and north of the River Clyde- it is mostly centred around Loch Lomond. The Stewarts of Darnley had also had close links with France and in particular the Garde Écossaise for over a century. This earl of Lennox’s father led a short rebellion during the early years of James IV’s reign, but most of that was smoothed over in the end. In all honesty I don’t know that much about Matthew personally, except that he pops up a lot in government and court records (and there was also a very delicate case that came before the council in 1508 involving his daughter). I will need to look into him further. He died at Flodden- his son was the earl of Lennox who then died at Linlithgow Bridge in 1526, and his grandson married Margaret Douglas, daughter of the earl of Angus, and was the father of the infamous Lord Darnley who married Mary I.

Alexander Hume, 3rd Lord Hume and Great Chamberlain of Scotland in 1511. In the early sixteenth century, the Humes were borderers par excellence. Lord Hume was Warden of the East and Middle Marches, and had a great many kinsmen and friends (and a fair few enemies) throughout the borders counties. His great -grandfather and, especially, his father had also carved out a role for themselves at the centre of government. In the first couple of years of James IV’s reign, the Humes and even more so their neighbours the Hepburns (family of the earls of Bothwell) were practically running the show- this may have been one of the main causes of the earl of Lennox’s rebellion. In 1506 Alexander succeeded his father as 3rd Lord Hume and Great Chamberlain (less of an active administrative role by this point, but it still entitled the holder to access the centre of government and the royal household). He fought at Flodden but escaped- unfortunately for the Humes, rumours later circulated that they were partly responsible for the king’s death in the battle, and indeed James IV’s son the earl of Moray is supposed to have accused Hume of this in later years. Hume was one of the men who supported the appointment of the Duke of Albany as governor in 1515, after Margaret Tudor’s marriage to the Earl of Angus, but he very quickly grew dissatisfied with the duke, and by Christmas of the same year he had crossed the Border to join Margaret in Morpeth. After another few months of shenanigans in the Borders, Hume and his brother were captured by the Duke of Albany and executed in 1516- their heads were displayed above the Tolbooth in Edinburgh. This resulted in even more drama but I’m getting off topic and I think enough has been said on Lord Hume to give you an idea of his, um, colourful character. He is *supposed* to have had an affair with the second wife of the 5th Earl of Angus, Katherine Stirling, and was later the second husband of James IV’s last mistress Agnes Stewart, Countess of Bothwell.

(Restored windows in Stirling Castle Great Hall, the 20th century glass bearing the coats of arms of earls from the reign of James IV. The hall dates from around 1503 and was restored in the 1960s to look like it may have done in James IV’s time. It’s bright yellow and gorgeous and I’m furious it’s never used in anything).

Andrew Gray, Lord Gray and Justiciar in 1511- A lord of parliament like Hume, but with a less committed following, whose main interests lay in Angus (the region). Andrew Gray was one of the men who backed James IV in his rebellion against his father in 1488. Indeed, late sixteenth century legend has it that he was the one responsible for James III’s death- either arranging his murder in the mill at Bannockburn or carrying it out himself. However he acted as a loyal servant of the Crown until the end of his life, and as the justiciar he would have accompanied the king and other important nobles on justice ayres across the kingdom (and held some of his own). Traditionally, there had been two justiciars in Scotland- one for Scotia, north of the Forth, and one for south of the Forth (usually identified with Lothian- there was a third sometimes for Galloway as well). In the 1490s, Lord Drummond and the Earl of Huntly had also acted as justiciars at various points, but from around 1501 Lord Gray appears to have been the only justiciar. He died in early 1513.

Master Gavin Dunbar, Archdeacon of St Andrews and Clerk Register in 1511. Not to be confused with either of the poets Gavin Douglas or William Dunbar, nor with his nephew, Gavin Dunbar, Archbishop of Glasgow. This Gavin Dunbar was a graduate of the University of St Andrews and had travelled to France in at least one embassy in 1507. Technically, in 1511, Dunbar was clerk of the rolls, clerk register, and clerk of council- which is a lot of writing (if we assume he did it all himself, which I doubt). In 1518, Dunbar succeeded to William Elphinstone’s old diocese of Aberdeen and showed a decent amount of interest in the diocese. He undertook an extensive rebuilding programme at St Machar’s Cathedral and provided the nave with the wonderful heraldic ceiling that can still be seen today.

Master Patrick Paniter, Secretary to the King (among other things) in 1511. A very interesting individual. Paniter’s family were from the area around Montrose, in Angus, and he attended university at the College of Montaigu in Paris (as did many of his compatriots, including the contemporary theologian John Mair). He was clearly a bright spark since upon his return to Scotland he seems to have been appointed tutor to James IV’s young son Alexander and the two had a good relationship, with Paniter writing to the young archbishop as ‘half his soul’ and Alexander in turn keeping in touch with his ‘dear teacher’ while on the continent. By that time though, Patrick had moved onto bigger things, since the king appointed him royal secretary some time around 1505. Eventually Paniter became one of James IV’s most influential servants- in 1513, the English Ambassador Dr Nicholas West described the secretary as the man “which doothe all with his maister”. Of course Paniter enriched himself quite a bit too, becoming, among other things, archdeacon and chancellor of Dunkeld, deacon of Moray, rector of Tannadice, and Abbot of Cambuskenneth and, controversially, James IV also attempted to appoint him as preceptor of Torphicen. Paniter helped to direct the artillery at Flodden but unlike both his patron and former pupil, he survived the battle. He is also *reputed* to have been the father of David Paniter, bishop of Ross, by King James IV’s cousin Margaret Crichton.

The men whose careers I’ve outlined above all witnessed the majority of royal charters issued under the great seal in the first half of 1511 (by modern dating). A few others also appeared frequently- for example, Robert Colville of Ochiltree, John Hepburn the Prior of St Andrews, and George Crichton, Abbot of Holyrood. Obviously the make-up of the council changed frequently too. Equally though charters are not necessarily the only or best indication of who would have been part of the king’s ‘council’ and there are other officials and nobles whom we know were close to the king but rarely appear on these, either due to the date range or just their own status- Andrew Forman, bishop of Moray; the 1st earl of Bothwell (before his death); the 5th earl of Angus (in the 1490s anyway- I told you it was a complex relationship); John, Lord Drummond (especially in the 1490s), and others.

But why did I bother giving those long biographies? Well partly to demonstrate the complexity of individual stories in sixteenth century Scottish politics and that they did do important and interesting things. Also since several of these men held opposing political views and family interests, but were usually expected to cooperate at the centre of government, it underlines the point that sixteenth century Scottish politics was a bit more complex than ‘The Clans Are Fighting’. And also this is partly to show that we DO actually have this info at our disposal. Most tv shows and films just choose not to use it.

But the real reason for this long rant was mostly so I could ask, given the info I’ve provided above, WHO THE HELL IS THIS SUPPOSED TO BE:

It’s a bad picture, I know and again, nothing against the actor who seems to be having a lot of fun with the role. But other than James IV, Margaret, and the three Douglases (one of whom has the wrong name and they all have the wrong clothes and also none of them should have been there), this is the only named character in that scene. And I cannot for the life of me work out who he is supposed to be.

He’s given the name Alexander Stewart. As we have seen, there was certainly an Alexander Stewart on the king’s council in 1511- the king’s son who was born c. 1493 and was also Archbishop of St Andrews. Now this this man very much NOT younger than Margaret Tudor, and very unlike the boy Erasmus described, and even though that Alexander died fighting in battle I’m not sure he would have spent most of his days brandishing daggers and yelling abuse at the Douglases in council meetings. He is also probably not our man because as I discussed here, I think the archbishop’s supposed to be counted among James IV’s children in that other scene where this tv series wrongly implies that Margaret Tudor played nursemaid to all of James’ children (again, not one of those kids should have been in the room and it’s really weird that none of them seem to have aged even though two of them were probably older than Mary Tudor).

So who is he? There were definitely other Alexander Stewarts who were both associated with the royal household and who were kicking about sixteenth century Scotland more generally. One was in fact the half-brother of the Duke of Albany- but he really doesn’t seem to have played any role in government, and mostly he appears when his expenses were met by his cousin the king, presumably out of familial responsibility (see also the king’s other probable cousins Christopher, the Danish page, and Margaret Crichton). Another one was Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, a more distant cousin of the king (he was the grandson of Joan Beaufort), but he was dead by 1511 and his son was called John- meanwhile his half-sister Agnes, the king’s mistress, was enjoying the profits of the earldom. In character he seems to come across more like an earlier earl of Buchan, that infamous Alexander Stewart who got the nickname ‘The Wolf of Badenoch’- but he died over a century before 1511. There are probably a couple of other Alexander Stewarts I’ve missed out- it’s a popular name- but none I can think of who would have had any sort of reason to be on the king’s council.

Also worth mentioning I’m not sure what he means when he accuses the Douglases of ransacking his family’s ‘Lowland lands’. That’s just so confusing I won’t even get into it.

ANYWAY there was a point to all this ranting. As I said above, people should absolutely enjoy this show if they want to. However, two things may be said- firstly that if a show is already fairly inaccurate about English history, I am always willing to bet that they have been 200% more inaccurate about Scotland- to the extent that it’s not even inaccuracy any more, it’s just a completely different world and story.

Secondly, when the producers or whoever (and no disrespect to them necessarily except when they say this) claim that they did their research and say stuff like "we are totally with her story, we're up in Scotland, we're sort of Spanish Princess meets Outlander" I would like to remind everyone that not only is this waaaay less accurate than even Outlander could manage:

- Probably none of the kids in the first scene should have been there

- Probably none of the men in the council scene should have been there (except James, obviously)

- The costumes are the same nonsense as usual.

- There were only five named historical figures and somehow they still managed to balls up one of the names (again, Angus Douglas??? How did they even manage to mess that one up??)

- The sixth named figure is a completely made up individual with a vaguely plausible name who appears to serve no other purpose than to get stabby and foul-mouthed and show that The Clans(TM), as they put it, Are Fighting Again.

- It’s heavily implied that absolutely nobody involved in the production has ever looked at a map of Scotland properly, or tried to work out where any of these guys come from. Which is amazing given it’s literally attached to the map of England. Essentially, the land and regions matter in Scottish history and it’s one of the biggest things that period dramas misunderstand or simplify.

- As usual the architecture is slightly off, though it could be worse. Despite the claim that ‘we’re up in Scotland’, suffers from the usual feeling that actually no camera crew made it any further north than Alnwick (though the CGI Warwick-Edinburgh thing kind of worked.).

- Everyone is a classic stereotype of the Barbarian Uncultured Scot and the only sop thrown is the bit with James and the teeth.

- The above thus implies that the creators have not considered that Scotland could ever have anything of any cultural value, such as a talented poet they are literally showing on screen or a bunch of bishops and other churchmen they aren’t. Which is just European Renaissance stuff, and not even getting into the highly impressive cultural world of Gaelic Scotland and Ireland.

- Everyone Is Sexist Except the English (for god’s sake, it’s the 16th century)

- Person wanders around yelling that they are the king/queen and expects this to work. No.

- Bruce and Wallace are (accurately) mentioned a lot but it’s probably more because that’s the only people the writers have heard of, rather than any nod to 16th century literary and historical tradition. No James Douglas or Thomas the Rhymer or St Margaret is expected to make an appearance.

- Incredibly evident that nobody has opened a book on the reign of James IV or even one of those dodgy biographies of Margaret Tudor. I’m not even entirely convinced that they read Gregory’s novel, which is supposed to be their source material.

So what do we actually have?

- James IV’s interest in medicine and alchemy and other proto-sciences is given a nod with the teeth thing

- We know there were black musicians at James IV’s court and that was shown.

- It is implied Margaret Tudor has lost babies. This is true. However there are still allegedly two alive so the maths doesn’t add up.

- Some modern Scottish accents, one done by a Northern Irishman.

- A handful of historical figures’ names scattered around willy-nilly (one of them incorrect).

The overall point is, once again, if you thought the inaccuracy about English history was bad, there isn’t even any inaccuracy in the Scottish stuff, because it’s not even sixteenth century Scotland any more. And that wouldn’t be an issue if the creators didn’t keep going on about how this is what really happened.

(King’s College, University of Aberdeen, with Bishop Elphinstone’s chapel to the right. On other sides of the chapel, the coats of arms displayed include those of James IV, Margaret Tudor, and Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St Andrews- I think the Duke of Ross might be there too, can’t remember)

- Most of my sources for this included Norman McDougall’s biography of James IV, Macfarlane’s biography of Elphinstone, good general overviews, and a lot of primary sources- especially the register of the Great Seal. Also general knowledge about Scotland because, you know, I’m from there. HOWEVER if anyone wants a source for a specific detail I should be able to find that reasonably easily. Just let me know.

#Scotland#Scottish history#British history#Margaret Tudor#period drama#didn't know what to tag as sorry

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

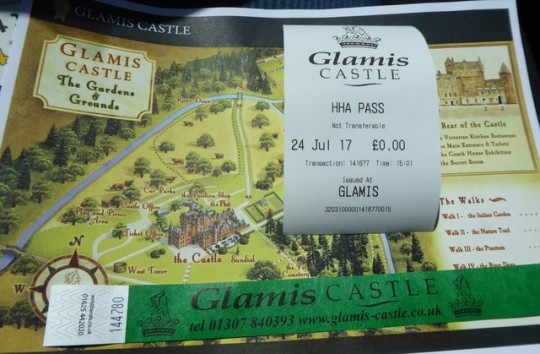

Glamis Castle Glamis Angus Scotland

I visited the castle during my tour of Scotland in July 2017.

********************************************

In 1034 King Malcolm II was murdered at Glamis, where there was a Royal Hunting Lodge. In William Shakespeare's play Macbeth, the eponymous character resides at Glamis Castle, although the historical King Macbeth (d. 1057) had no connection to the castle.

By 1376 a castle had been built at Glamis, since in that year it was granted by King Robert II to Sir John Lyon, Thane of Glamis, husband of the king's daughter. Glamis has remained in the Lyon (later Bowes-Lyon) family since this time. The castle was rebuilt as an L-plan tower house in the early 15th century.

The title Lord Glamis was created in 1445 for Sir Patrick Lyon (1402–1459), grandson of Sir John. John Lyon, 6th Lord Glamis, married Janet Douglas, daughter of the Master of Angus, at a time when King James V was feuding with the Douglases. In December 1528 Janet was accused of treason for bringing supporters of the Earl of Angus to Edinburgh. She was then charged with poisoning her husband, Lord Glamis, who had died on 17 September 1528. Eventually, she was accused of witchcraft, and was burned at the stake at Edinburgh on 17 July 1537. James V subsequently seized Glamis, living there for some time.

In 1543 Glamis was returned to John Lyon, 7th Lord Glamis. In 1606, Patrick Lyon, 9th Lord Glamis, was created Earl of Kinghorne. He began major works on the castle.

During the English civil war, soldiers were garrisoned at Glamis. In 1670 the Earl, returned to the castle and found it uninhabitable. Restorations took place until 1689, including the creation of a major Baroque garden.

Glamis Castle has been the home of the Lyon family since the 14th century, though the present building dates largely from the 17th century. Glamis was the childhood home of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, wife of King George VI. Glamis Castle is now the home of the Earl and Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne,

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancestors who fought in battle against ancestors

Ancestors who fought in battle against ancestors

1. Battle of Flodden 1513 (English victory over Scots)

Fought on Scottish side: John Huntar, 14th Laird of Hunterston (killed in battle)

Fought on Scottish side: Sir David Home, of Wedderburn (killed in battle)

Fought on Scottish side: George Douglas, Master of Angus (killed in battle)

Fought on Scottish side: Robert Craufurd, 5th Laird of Auchenames (killed in battle)

Fought on English side: Sir…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Sir John Kirk and the Resonance of Slavery

Slavery as a tangible fact is not something one would particularly associate with Angus, more than any other part of the British Isles, though the county of course had its connections with that trade. Interesting and little-known material about the decent and doubtless God-fearing lairds who quietly owned slaves far away, back in the day, can be unearthed through web sites like Legacies of British Slave Ownership, and though it may seem churlish to name and shame those associated with that business after all these years (people who in themselves doubtless led complex and rich lives), it can still be instructive as an eye-opener.

Among the interesting data is that concerning former slave owners who claimed compensation from the British government when slavery in the British Empire was abolished and they were financially disadvantaged. A cursory search through the records reveals the follows Angus folk as former slave owners: David Langlands of Balkemmock, Tealing, Alexander Erskine of Balhall, David Lyon of Balintore Castle, George Ogilvie of Langley Park, James Alexander Pierson of The Guynd, Thomas Renny Strachan of Seaton House, St Vigeans, Mary Russell of Bellevue Cottage, David McEwan and James Gray of Dundee, the 7th Earl of Airlie.

There is more information surrounding the Cruickshank family, who lived at Keithock House, Stracathro House and Langley Park. Alexander Cruickshank of Keithock was born in 1800 and married his cousin, Mary Cruickshank of Langley Park (formerly Egilsjohn or - colloquially - Edzell's John). In the middle of the 19th century Alexander unsuccessfully attempted to claim compensation for the loss of slaves owned on the Langley Park estate on the island of St Vincent. The whole family's fortunes were inextricably linked with slavery. Patrick jointly owned the estates of Richmond, Greenhill and Mirton in St Vincent with his brother James who was compensated £23,000 by the government following slavery abolition in 1833. The St Vincent estates had more than 800 slaves. Originally from Wartle in Aberdeenshire, the money to buy the Egilsjohn estate in Angus came from a fortune made in the Caribbean; its name was even changed to commemorate the St Vincent estate name of Langley. The Angus estates of Stracathro and Keithock followed. But we are told (Baronage of Angus and Mearns, p. 64) that Alexander Cruickshank's 'affairs eventually got embarrassed - and he returned to Demerara, where he shortly afterwards made his demise, leaving a son and daughter.'

Emigration to the colonies was by no means a passport of quick riches to those who went there with slender means to begin with. John Landlands, son of a tenant farmer from Haughs of Finavon, went to Jamaica in 1749 and found that his promised employment did not exist, though he was helped to secure another post at the vividly named Treadways Maggoty estate. In time he acquired his own coffee plantation, complete with valuable slaves. On his death he provided for his mistress/housekeeper and his natural son born to her, but the estate of Roseberry was burdened by debt and had to be disposed of by his cousin back home in Angus.

There was less known commercial speculation in the slave trade in Angus ports than in other places, though there are records held in Montrose Museum of a business deal from 1751 concerning the ship Potomack, whose master Thomas Gibson struck a deal with merchants Thomas Douglas and Co to travel with cargo to Holland and thence to west Africa and there pick up slaves for the North American market. Researchers reckon that some 31 Montrose vessels were engaged in human slave trafficking, though records survive for only four ships (the other three being the Success, the Delight, and the St George).

One Montrose family of the 18th century who went on to great things financially were the Coutts family, ancestors of the private banking dynasty which migrated to London later and dealt with the fortunes of royals and the nobility. John Coutts (born 1643) was Lord Provost of the Angus burgh five times between 1677 and 1688 (having been made a councillor in 1661). the family were involved in the Virginia tobacco trade and doubtless incidentally involved to some extent in slave ownership. John's third son Thomas went to London and was one of the promoters of the 'Company of Scotland, trading to Africa and the Indies', better known as the company who initiated the doomed Darien Scheme. A grandson of the first John Coutts was another John (son of Patrick), among those in the family who left Montrose for business opportunities further south.

John Kirk - Doctor! Botanist! Knight! Our Man in Zanzibar!

There were few places as strange to the intrepid foreigner in the mid 19th century as Zanzibar, even in an age when the whole continent of Africa held a jewel-like fascination for Europeans. The island was just off the continental coast but was truly a place apart. It had in effect been colonised and annexed before any Western interest in the place by an Arab dynasty from the north. The ruler of Oman, Seyyid Said, made the African island his capital in 1838 and brilliantly maintained his power through diplomacy with the British East India Company and a cannily managed business acumen. The Arab management of African slaves more than matched the newer European-sponsored slave trade operating in west Africa. Throughout Seyyid Said's rule it continued unabated and Zanzibar was its unashamed fulcrum, dispatching human cargo and attendant misery across the Indian Ocean. Alastair Hazell states that the mid-19th century population of the island was possibly 100,000, or which around half were slaves. Said had personally transformed his new centre of operations 'from a mere backwater, a slave market with a fort, to the largest and most prosperous trading city of the western Indian Ocean'.

Gold, ivory and gum copal were other products which flowed out of the continent via the island, but it was the process of the oldest institution on Zanzibar, the slave market outside the Customs House, which was the most outstanding element of that market place to outsiders; here described by the English traveller Sir Richard Burton. It was a place, he said:

where millions of dollars annually change hands under the foulest of sheds, a long, low mat-roof, supported by two dozen tree-stems... It is conspicuous as the centre of circulation, the heart from and to which twin streams of blacks are ever ebbing and flowing, whilst the beach and waters opposite it are crowded with shore boats.

The slave market was in the centre of town and here every year many thousands of bagham, untrained slaves, were tethered and publicly auctioned. In the mid-1850s, Hazell tells us, able-bodied young men could be bought for $4-$12 - 'about the prince of a donkey'. Girls and women were sold for sex, passed on many times via different owner/abusers. A premium was paid for 'exotics' from India or fair haired unfortunates from as far afield as the Caucasus.

The Boy from Barry

Step up John Kirk. The latest biographer of John Kirk - Alastair Hazell - makes the fundamental mistake of stating that Kirk was born in Barry, in Fife! This is a shame because his book, The Last Slave Market, is a well-researched account of this important figure who did much personally to end the intolerable anomaly of Zanzibar's slaving in a time when many cynically turned a blind eye to it. John was the third of his name in succession, following his grandfather (a baker) and father, who was born in St Andrews in 1795 (which perhaps explains Hazell's error). The Rev. Kirk was appointed minister of Barry in June 1824 and transferred to nearby Arbirlot in 1837. In the religious turmoil of the times he joined the Free Church and was minister of the Free Church in Barry from 1843 until his death in 1858. The minister was 'a man of cultivated mind, of a deportment becoming his high calling, and of a conversation that savoured of the things of Christ'. His wife was Christian Guthrie, daughter of the Rev. Alexander Carnegie, minister of Inverkeilor.

John Kirk as a young doctor.

The youngest John was he second of four children, born 19 December 1832 and must have inherited much of his iron-clad morality from his parents. The only other sibling who seems to have attained any prominence was his elder brother, Alexander Carnegie Kirk, born in 1830. He became a noted naval engineer, but unlike John did not take part in any kind of public life, dying in Glasgow in 1892.

The explorer's eldest brother.

Early Career and Into Africa

Kirk qualified as a doctor and went on to serve in the Crimea War in 1855. (His interest in botany was evident in Edinburgh, where he studied in the faculty of arts at first before switching to medicine.) Learning Turkish, he travelled widely in the Middle East, mainly pursuing botanical interests. His most significant appointment was that of a naturalist accompanying the famous David Livingstone on an expedition to east Africa in 1858. This second expedition of Livingstone's, exploring the Zambesi region, did not go entirely smoothly. Livingstone was no great communicator and preferred either his own company or that of native Africans. His brother Charles was also part of the party and was a more petty character than David, arguing with colleagues and dismissing some of them. Kirk generally got on tolerably well with Livingstone - both were doctors and of course Scots - and also accepted his plans and decisions even when these looked ill-judged and even foolhardy. But Livingstone, driven by instinct and his own demons, was at times looked upon as a madman by his younger colleague. On 18 April 1874 he was one of the pall-bearers who carried Livingstone's coffin into a funeral ceremony in Westminster Abbey. (This was despite the fact that Livingstone's chief mythologiser, Henry Morton Stanley, tried his damnedest to blacken's Kirk's name on the false basis that the doctor had not done all he could to assist the great man in his last expedition.)

John Kirk returned to Britain in 1863, but three years later he was back in a different part of Africa, appointed as a medical officer in Zanzibar. He soon became Assistant Consul and then Resident. He had been appointed Consul in 1873, succeeding Henry Adrian Churchill, who had been actively working towards the abolition of the slave market on the island. Churchill's health broke down to such an extent that Kirk advised him to return to the U.K. in 1870.

The final defeat of the slave trade in the island was accomplished by Kirk's astonishing guile and nerve. While the years in which he served primarily as a doctor in the consulate were quiet and he took no active part in public life or against slavery, there was one incident which marked him out as a risk taker. This was in 1866 when he joined in the successful attempt to smuggle the sultan's sister out of the territory. Seyidda Salme had become pregnant by a German and was at risk of death if she had remained in Zanzibar. For much of the time, Kirk pursued his own interests in Africa, collecting information about botany, trade, slavery, in an even handed and non-judgemental fashion. More of a pragmatist than the strange visionary Livinstone, he was caught between the rock and hard place of the British government and the East India Company, which often had differing ideas about slavery and much else. In 1873 he was put in an invidious position of receiving two contradictory instructions from London. The first ordered him in no uncertain terms to give the Sultan the ultimatum that he should close the slave market and cease all trade in slaves, or else the British government would blockade the island. The second order warned Kirk that no blockade was to be enforced, for fear that it would drive the territory to crave the protection of the French. Kirk only showed the first communication to the Sultan, with the result that Barghash caved in within two weeks and the slave market was closed forever.

Despite the best efforts of Kirk and his successors, slavery actually surreptitiously survived the closure of Zanzibar's public slave market. Special Commissioner Donald Mackenzie visited the island and its neighbour Pemba in the last decade of the 19th century and found that slavery was still flourishing in the agricultural estates:

In Zanzibar a good many people had been telling me how happy and

contented the Slaves were in the hands of the Arabs; in fact, they would

not desire their freedom. At Chaki Chaki I walked into a tumble-down

old prison. Here I found a number of prisoners, male and female,

heavily chained and fettered. I thought surely these men and women

must be dreadful criminals, or murderers, or they must have committed

similar crimes and are now awaiting their doom. I inquired of them all

why they were there. The only real criminal was one who had stolen a

little rice from his master. All the others I found were wearing those

ponderous chains and fetters because they had attempted to run away

from their cruel masters and gain their freedom— a very eloquent commentary on the happiness of the Slaves!

The British Consulate, Zanzibar.

Kirk's Later Years and Legacy

Kirk returned to Britain finally in 1886, settling in Kent. His awards included the K.C.M.G., G.C.M.G., K.C.B., plus the Patron's Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society. The welfare of Africa still concerned him and in 1889-90 he attended the Brussels Africa Conference as British Plenipotentiary. In later years John Kirk grew progressively blind but he maintained his interest in the natural world. He died at the age of 89 and was buried in St Nicholas's Churchyard in Sevenoaks. Among the tributes paid to him was one by Frederick Lugard, Governor General of Nigeria: 'For Kirk I had a deep affection which I know was reciprocated. He was to me the ideal of a wise and sympathetic administrator on whom I endeavoured to model my own actions and to whose inexhaustible fund of knowledge I constantly appealed.'

Substantial records survive concerning Kirk, including the journals he kept on the expedition with Livingstone, Apart from that there are his contributions and discoveries in zoology, biology, a substantial corpus of photographs(over 250). He maintained close connection with Kew Gardens until his death. The Kirk Papers have been secured for the future in the National Library of Scotland. As far as I know, there is no memorial to Sir John Kirk at Barry, but if not, there definitely should be.

Sultan of Zanzibar, Sayyid Sir Barghash bin Sa'id (ruled 1870-1888).

Selected Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Kirk_(explorer)

John Langlands: An Aberlemno Slave Owner

C. F. H., 'Obituary: 'Sir John Kirk,' Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygeine, volume 15, issue 5-6 (15 December 1921), p. 202.

Hazell, Alastair, The Last Slave Market: Dr John Kirk and the Struggle to End the African Slave Trade (London, 2011).

Low, James L., Notes On The Coutts Family (Montrose, 1892).

MacGregor Peter, David, The Baronage of Angus and Mearns (Edinburgh, 1856).

Mackenzie, Donald, A Report on Slavery and the Slave Trade in Zanzibar, Pemba, and the Mainland Protectorates of East Africa (London, 1895).

McBain, J. M., Eminent Arbroathians (Arbroath, 1897).

Scott, Hew, Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae (volume 5, new edition, Edinburgh, 1925).

Wild, H., 'Sir John Kirk,' Kirkia, volume 1 (1960-61), pp. 5-10.

0 notes

Text

History of The Canadian Open

The Canadian Open (French: L'Omnium Canadien) is a professional golf tournament in Canada, first played 113 years ago in 1904. It is organized by the Royal Canadian Golf Association / Golf Canada. Played annually continuously since then, except for some years during World War I and World War II, the Canadian Open is the third oldest continuously running tournament on the PGA Tour, after The Open Championship and the U.S. Open.

Tournament As a national open, and especially as the most accessible non-U.S. national open for American golfers, the event had a special status in the era before the professional tour system became dominant in golf. In the interwar years it was sometimes considered the third most prestigious tournament in the sport, after The Open Championship and the U.S. Open. This previous status was noted in the media in 2000, when Tiger Woods became the first man to win The Triple Crown (all three Opens in the same season) in 29 years, since Lee Trevino in 1971. In the decades preceding the tournament's move to an undesirable September date in 1988, the Canadian Open was often unofficially referred to as the fifth major. Due to the PGA Tour's unfavorable scheduling, this special status has largely dissipated, but the Canadian Open remains a well-regarded fixture on the PGA Tour.

The top three golfers on the PGA Tour Canada Order of Merit prior to the tournament are given entry into the Canadian Open. However, prize money won at the Canadian Open does not count towards the Canadian Tour money list.

Celebrated winners include Hall of Fame members Leo Diegel, Walter Hagen, Tommy Armour, Harry Cooper, Lawson Little, Sam Snead, Craig Wood, Byron Nelson, Doug Ford, Bobby Locke, Bob Charles, Arnold Palmer, Kel Nagle, Billy Casper, Gene Littler, Lee Trevino, Curtis Strange, Greg Norman, Nick Price, Vijay Singh, and Mark O'Meara. The Canadian Open is regarded as the most prestigious tournament never won by Jack Nicklaus, a seven-time runner-up. Diegel has the most titles, with four in the 1920s.

In the early 2000s, the tournament was still being held in early September. Seeking to change back to a more desirable summer date in the schedule, the RCGA lobbied for a better date. When the PGA Tour's schedule was revamped to accommodate the FedEx Cup in 2007, the Canadian Open was rescheduled for late July, sandwiched between three events with even higher profiles (The Open Championship the week prior, the WGC-Bridgestone Invitational the week after, and the PGA Championship the week after that). The tournament counts towards the FedEx Cup standings, and earns the winner a Masters invitation.

Courses Glen Abbey Golf Course has hosted the most Canadian Opens, with 27 to date. Glen Abbey was designed in 1976 by Jack Nicklaus for the Royal Canadian Golf Association, to serve as the permanent home for the championship. In the mid-1990s, the RCGA decided to move the championship around the country, and continues to alternate between Glen Abbey and other clubs.

Royal Montreal Golf Club, home of the first Open in 1904, ranks second with nine times hosted. Mississaugua Golf & Country Club has hosted six Opens.

Three clubs – Toronto Golf Club, St. George's Golf and Country Club, and Hamilton Golf and Country Club – have each hosted five Opens.

Three clubs have each hosted four Opens: Lambton Golf Club, Shaughnessy Golf & Country Club, and Scarboro Golf and Country Club.

The championship has for the most part been held in Ontario and Quebec, between them having seen all but nine Opens. New Brunswick had the Open in 1939, Manitoba in 1952 and 1961, Alberta in 1958, and British Columbia in 1948, 1954, 1966, 2005 and 2011.

History

The Royal Montreal Golf Club, founded in 1873, is the oldest continuously running official golf club in North America. The club was the host of the first Canadian Open championship in 1904, and has been host to eight other Canadian Opens. The 1912 Canadian Open at the Rosedale Golf Club was famed American golfer Walter Hagen's first professional competition.[2] In 1914, Karl Keffer won the event, being the last Canadian-born champion.

Englishman J. Douglas Edgar captured the 1919 championship at Hamilton Golf and Country Club by a record 16-stroke margin;[3] 17-year-old amateur prodigy Bobby Jones (who was coached by Edgar) tied for second. The 1930 Canadian Open at Hamilton was another stellar tournament. Tommy Armour blazed his way around the course over the final 18 holes of regulation play, shooting a 64. Four-time champion Diegel and Armour went to a 36-hole playoff to decide the title. Armour shot 138 (69-69) to defeat Diegel by three strokes.[4]

Toronto's St. Andrews Golf Club hosted the Open in 1936 and 1937 – the only course to hold back-to-back Opens until the creation of Glen Abbey – before it felt the impact of the growth of the city, and was ploughed under to allow for the creation of Highway 401. The Riverside Golf and Country Club of Saint John, New Brunswick was host to the 1939 Canadian Open where Harold "Jug" McSpaden was champion. This was the only time the Open has been held in Atlantic Canada.[5]

Scarboro Golf and Country Club in eastern Toronto was host to four Canadian Opens: 1940, 1947, 1953, and 1963. Three of these events were decided by one stroke, and the only time the margin was two shots was when Bobby Locke defeated Ed "Porky" Oliver in 1947. With his win at Scarboro in 1947, the golfer from South Africa became just the second non-North American winner of the Canadian Open. Locke fired four rounds in the 60s to finish at 16-under-par, two strokes better than the American Oliver. After the prize presentation Locke was given a standing ovation, and was then hoisted to shoulders by fellow countrymen who were then residents of Canada.

In 1948, for the first time, the Canadian Open traveled west of Ontario, landing at Shaughnessy Heights Golf Club in Vancouver, British Columbia, where Charles Congdon sealed his victory on the 16th hole with a 150-yard bunker shot that stopped eight feet from the cup. The following birdie gave him the lead, and Congdon went on to win by three shots.

Mississaugua Golf & Country Club has hosted six Canadian Opens: 1931, 1938, 1942, 1951, 1965, and 1974. The 1951 Open tournament was won by Jim Ferrier, who successfully defended the title he had won at Royal Montreal a year earlier. Winnipeg's St. Charles Country Club hosted the 1952 Canadian Open, and saw Johnny Palmer set the 72-hole scoring record of 263, which still stands after more than 60 years. Palmer's rounds of 66-65-66-66 bettered the old 1947 mark set by Bobby Locke by five shots. In 1955, Arnold Palmer captured the Canadian Open championship, his first PGA Tour victory, at the Weston Golf Club.

Montreal, Quebec's Laval-sur-le-Lac hosted the 1962 Open where Gary Player was disqualified after the first round, when he recorded the wrong score on the 10th hole. He had won the PGA Championship the week before. Californian Charlie Sifford attended the 1962 Canadian Open in part to raise the profile of African-American players on the PGA Tour. He was one of only 16 of the top 100 players on tour to play there in 1962.

Pinegrove Country Club played host to the Canadian Open in 1964 and 1969. Australian Kel Nagle edged Arnold Palmer and Raymond Floyd at the 1964 Open to become, aged almost 44 at the time, the oldest player to win the title. Five years later, Tommy Aaron fired a final-round 64 to force a playoff with 57-year-old Sam Snead. Aaron won the 18-hole playoff, beating Snead by two strokes (70-72).

The small town of Ridgeway, Ontario in the Niagara Peninsula was host of the 1972 Open at Cherry Hill Golf Club. A popular choice of venue, it drew rave reviews by the players, specifically the 1972 champion Gay Brewer, who called it the best course he had ever played in Canada, and Arnold Palmer, who suggested the Open be held there again the following year. In 1975, Tom Weiskopf won his second Open in three years in dramatic fashion at the Blue Course of Royal Montreal's new venue, defeating Jack Nicklaus on the first hole of a sudden-death playoff, after almost holing his short-iron approach. Windsor, Ontario's Essex Golf & Country Club was host of the 1976 Canadian Open, where Jack Nicklaus again finished second, this time behind champion Jerry Pate. Essex came to the rescue late in the game, when it was determined that the newly built Glen Abbey was not yet ready to host the Canadian Open. The 1997 Open at Royal Montreal was the first time Tiger Woods ever missed a professional cut, after winning the Masters Tournament a few months before.

Nick Price's second Canadian Open win in 1994 Angus Glen Golf Club was host to two recent Canadian Opens, 2002 and 2007. In 2007 Jim Furyk became one of a few golfers who have won two consecutive Canadian Open titles, joining James Douglas Edgar, Leo Diegel, Sam Snead and Jim Ferrier. Angus Glen owns the unique distinction of having each of its two courses (North and South) host the Canadian Open.

Glen Abbey Golf Club of Oakville, Ontario has hosted 27 Open Championships (1977–79, 1981–96, 1998–2000, 2004, 2008–09, 2013, 2015), and has crowned 22 different champions. The 11th hole at Glen Abbey is widely considered its signature hole, and begins the world-famous valley sequence of five holes from 11 to 15. The picturesque 11th is a 459-yard straightaway par-4, where players tee off 100 feet above the fairway, which ends at Sixteen Mile Creek, just short of the green. John Daly left his mark, and a plaque is permanently displayed on the back tee deck, recounting Daly's attempt to reach the green with his tee shot. His ball landed in the creek.

In 2000, Tiger Woods dueled with Grant Waite over the final 18 holes, before finally subduing the New Zealander on the 72nd hole with what is probably[according to whom?] the most memorable shot of his illustrious career so far[when?]. Holding a one-shot advantage, Woods found his tee shot in a fairway bunker, and after watching Waite put his second shot 30 feet from the hole, decided he had no choice but to go for the green[citation needed]. Woods sent a 6-iron which carried a lake and settled on the fringe just past the flag, which was 218 yards away, and then chipped to tap-in range for the title-clinching birdie.[6] With the victory, Woods became only the second golfer to capture the U.S. Open, Open Championship and Canadian Open in the same year, earning him the Triple Crown trophy.

In 2009, Mark Calcavecchia scored nine consecutive birdies at the second round, breaking the PGA Tour record.[7]

Canadian performances[edit] A Canadian has not won the Canadian Open since Pat Fletcher in 1954, and one of the most exciting conclusions ever seen at the Open came in 2004, extending that streak. Mike Weir had never done well at the Glen Abbey Golf Course, the site of the tournament that week. In fact, he had only made the cut once at any of the Opens contested at Glen Abbey. But Weir clawed his way to the top of the leaderboard by Friday. And by the third day at the 100th anniversary Open, he had a three-stroke lead, and many Canadians were buzzing about the possibility of the streak's end. Weir started off with a double bogey, but then went 4-under to keep his 3-stroke lead, with only eight holes left. Yet, with the expectations of Canadian observers abnormally high, there was another roadblock in the way of Mike Weir: Vijay Singh. Weir bogeyed three holes on the back nine but still had a chance to win the tournament with a 10-footer on the 72nd hole. When he missed the putt, the two entered a sudden-death playoff. Weir missed two more chances to win the tournament: a 25-foot putt for eagle on No. 18 on the first hole of sudden-death, and a 5-foot putt on No. 17, the second playoff hole. On the third playoff hole, Weir put his third shot into the water after a horrid drive and lay-up, and Singh was safely on the green in two. Singh won the Open and overtook Tiger Woods as the world's number one player.[8]

Canadian David Hearn took a two-shot lead into the final round in 2015. He still had the lead as late as the 15th hole, but was being closely pursued by three players ranked near the top of the Official World Golf Ranking – Bubba Watson, Jim Furyk, and Jason Day. All four golfers had chances to win right until the end. Hearn was overtaken by champion Day's three consecutive birdies to close the round; Day finished one shot ahead of Watson, who also birdied the final three holes, narrowly missing an eagle attempt on a final hole greenside chip that would have tied. Day's fourth career Tour triumph came after he had just missed a potential tying putt on the final hole at the Open Championship the previous week. Hearn finished third, the best result by a Canadian since Weir's near-miss in 2004.[9] In 2016, Canadian amateur Jared du Toit was only one stroke behind going into the final round, allowing him to play in the final group.

Brought to you by Lowville Golf Club

0 notes

Text

History of The Canadian Open

The Canadian Open (French: L'Omnium Canadien) is a professional golf tournament in Canada, first played 113 years ago in 1904. It is organized by the Royal Canadian Golf Association / Golf Canada. Played annually continuously since then, except for some years during World War I and World War II, the Canadian Open is the third oldest continuously running tournament on the PGA Tour, after The Open Championship and the U.S. Open.

Tournament As a national open, and especially as the most accessible non-U.S. national open for American golfers, the event had a special status in the era before the professional tour system became dominant in golf. In the interwar years it was sometimes considered the third most prestigious tournament in the sport, after The Open Championship and the U.S. Open. This previous status was noted in the media in 2000, when Tiger Woods became the first man to win The Triple Crown (all three Opens in the same season) in 29 years, since Lee Trevino in 1971. In the decades preceding the tournament's move to an undesirable September date in 1988, the Canadian Open was often unofficially referred to as the fifth major. Due to the PGA Tour's unfavorable scheduling, this special status has largely dissipated, but the Canadian Open remains a well-regarded fixture on the PGA Tour.

The top three golfers on the PGA Tour Canada Order of Merit prior to the tournament are given entry into the Canadian Open. However, prize money won at the Canadian Open does not count towards the Canadian Tour money list.

Celebrated winners include Hall of Fame members Leo Diegel, Walter Hagen, Tommy Armour, Harry Cooper, Lawson Little, Sam Snead, Craig Wood, Byron Nelson, Doug Ford, Bobby Locke, Bob Charles, Arnold Palmer, Kel Nagle, Billy Casper, Gene Littler, Lee Trevino, Curtis Strange, Greg Norman, Nick Price, Vijay Singh, and Mark O'Meara. The Canadian Open is regarded as the most prestigious tournament never won by Jack Nicklaus, a seven-time runner-up. Diegel has the most titles, with four in the 1920s.