#Gathering at Uisneach

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Eve of Bealtaine | Beltane

The Celtic Festival of Bealtaine/Beltane which marks the beginning of summer in the ancient Celtic calendar is a Cross Quarter Day, half way between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice. While the Bealtaine Festival is now associated with 1st May, the actual astronomical date is a number of days later. The festival was marked with the lighting of great bonfires that would mark a time of…

View On WordPress

#Ériu#Beltane#Beltany Stone Circle#Bonfires#Celtic Festival#Co. Donegal#Druidical ceremonies#Druids#Eve of Bealtaine#Gathering at Uisneach#Hill of Uisneach#Irish Mythology#MayDay#Quarter Days#Raphoe

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beltane

Beltane is a traditional Celtic pagan festival held on May 1st - the halfway point between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice - that celebrates the coming of summer and invokes fertility for the upcoming year. Beltane means 'fires of Bel', and honours the Celtic deity, Bel, by lighting candles and bonfires. During Beltane, Pagans believe that the veil between the physical and spiritual worlds is thin, making it easier to communicate with spirits and ancestors. It is also the time to honour the abundance of the earth and celebrate the growth and renewal of nature. The month of May in Irish is Bealtaine (byowl-thin-ah) and is named after the festival.

In Celtic times, Beltane marked the beginning of summer when cattle were brought out to the summer pastures. Rituals were performed to protect the cattle, crops, and people, and to encourage growth. Bonfires were lit and the people and their cattle walked around the bonfires. Household fires were doused and then re-lit from the Beltane bonfire. Holy wells were visited, and offerings made. The first water drawn from a holy well on May Day was thought to bring good luck, while washing your face with Beltane dew was thought to bring beauty and maintain youthfulness.

The May Queen is a central figure in Beltane celebrations, representing the fertility of the earth. In many traditions, the May Queen is chosen from the young women of the community and crowned with ribbons and flowers. She is often dressed in white, symbolizing purity and new beginnings. The Green Man is a Pagan deity associated with nature, fertility, and the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The Green Man is seen as the embodiment of the spirit of the forest and is closely tied to Beltane, which celebrates the arrival of summer and the fertility of the earth.

The presence of the May Queen and the Green Man at Beltane celebrations symbolizes the union of the earth and sky and represents the renewal of life and the promise of a bountiful harvest. Handfasting rituals sometimes occur at Beltane celebrations, where a couple declare their love and commitment to each other by having their hands tied together with ribbon or cord. Beltane gatherings were accompanied by a feast, and food and drink were offered to the Aos sídhe (the Celtic gods). Doors, windows, and livestock were decorated with white or yellow flowers.

A small tree or bush of hawthorn, rowan, holly, or sycamore is decorated with bright flowers, ribbons, and painted shells to make a May Bush. These customs are a relic of tree worship, and the intention is to invoke blessings from the tree spirit. In Victorian times, the custom of singing and dancing around the May Bush was replaced by the tradition of dancing with ribbons around a May Pole although this custom is more commonly seen in Britain and mainland Europe than in Ireland.

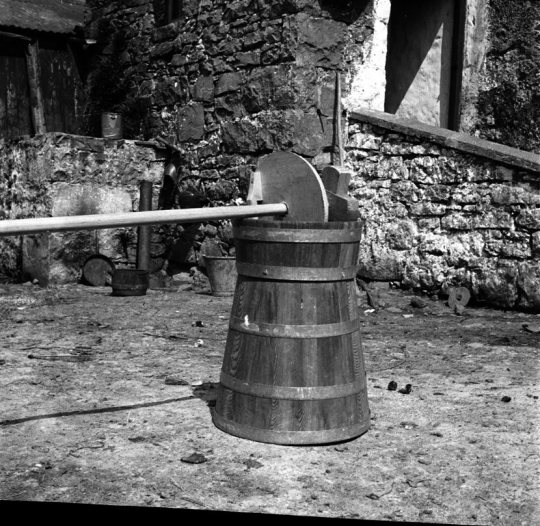

Many Beltane practices appeased the fairies. Black coal placed under butter churns prevented the theft of butter; branches from the May Bush tied to milk pails, and the tails of cattle hung in barns prevented the theft of milk. Cattle were brought to fairy forts and a small amount of their blood was poured on the earth to seek protection for the herd’s safety. Superstitions associated with Beltane include: to keep white horses in a barn, not to hang out clothes, or put fire ashes outdoors, and animals born on May 1st were an ill-fated omen. It was also considered bad luck to marry or give birth on the 1st of May. The hill of Uisneach (ish-nock) in County Westmeath is a traditional gathering place in Ireland for people celebrating Beltane. The “fires of Bel” are still lit annually at dusk after a torchlit procession by costume-clad participants. In 2017, the ceremonial fire was lit by the guest of honour, President Michael D. Higgins.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bealtaine Customs

Bealtaine is almost here!

Bealtaine (bee-YAL-tin-eh) is the ancient Irish fire festival that starts the night of April 30th- Oíche Bealtaine- and is celebrated May 1- Lá Bealtaine (though festivities can last longer). Bealtaine marks the beginning of summer. In modern Irish Catholic tradition, May is celebrated as the month of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

These quatations are all pulled from the dúchas.ie folklore collection. To learn more, go to https://duchas.ie

Significance of Fire

The ashes was never put out on May Day long ago.

-Mrs. French, Co. Mayo

A central theme of Bealtaine is fire, as it is with all the Irish fire festivals. On the eve of the holiday, all fires were put out. A central fire was lit at the heart of the island, which spread throughout:

On May Eve the Druids lit the great sacred fire at Tara and as the signal flames rose up high in the air and then a fire is to kindled on every hill in Erin; till the whole island is on fire with fires.

-Patrick Healy Co. Galway

A similar tradition has been revived at the Hill of Uisneach.

Having a bonfire and spreading the light from that central point would be a great way to honor the sacredness of fire and celebrate Bealtaine.

Back then, people would also guide their cattle through two bonfires at Bealtaine, to cleanse and bless them for good health and abundance. Speaking of cattle...

Protecting Cattle

The people also tie a piece of red cloth on each cows' tail. This they tie on in the morning before letting them out. They do this to prevent the fairies from taking the cow's milk. Sometimes they tie a horse-shoe-nail or "táirgne crúth" in the cow's tails

-Mrs. Nora Maloney, Co. Mayo

On May Eve now people sprinkle Easter water on all the crops, cattle etc. and on the boundary fence. Perhaps this is apart from it's religious aspect a survival of the old dread of 'pishogues' when people dreaded harm to their crops and cattle.

Long ago the people went out on May morning and blessed the cow with a lighting candle.

-Patrick Lally, Co. Galway

And while we're talking about protection...

Yellow Flowers- Festive Protection

In years gone by the people used to throw a primrose in the byre door so that the fairies would not take away the milk from the cows for the year. It was at May eve that they threw this primrose in the byre door.

-William J Mc Laughlin

It is the custom for children to pick May flowers or Marsh marigolds on the last evening in April. These they throw on the doorstep or on the windowsill.

-Mrs. Norah Maloney, Co. Mayo

The first of May is called May Day or (Lá Bealtaine). On the eve of this feast the children gather may-flowers and place them on the window sills of the houses.

-P. Mc Closkey

"Cow-slips were hung on the door that day to bring good luck for the year."

-Martin Costello, Co. Mayo

Try hanging up yellow flowers at your doors and windowsills for protection and good luck! If don't have any flowers, don't worry. There's another way to welcome in good luck...

May Day Dew

It is also said that if you get up early on that morning and wash your face with the dew on the grass you will be healthy during the year.

-Collected by Anthony Clark

They washed their faces in the dew on May morning before the sun rose and and they would not get sunburned again for the year.

- Mrs. French, Co. Mayo

If a person wanted to preserve their beauty , they would have to get up one hour before sun-rise and wash their face in dew off the grass on May morning.

-Collected by Amy Gilligan, Co. Mayo

That's all well and good, but there is something more sinister that May morning dew is useful for...

Baneful Butter Stealing

Long ago, on May morning, lots of old woman went out in the morning before the sun arose and swept the dew of the grass by pulling a long rope after them and calling, "Come all to me, come all to me.” This was a kind of witchcraft, taking away butter of other people’s milk.

-Collected by Rudy Stronge, Co. Donegal

It is also believed if one goes out early and milks the neighbour's cow, they will be able to get all the butter from that cow's milk so they will have double the supply while their neighbour will not get any.

Long ago on May morning some people used pull three ribs from the cow's tail and take clay from her hoofs and bring it home. Then that person would have butter from the cows she did this to and the person to whom the cows belonged would have none after churning.

-Michael Costello, Co. Mayo

Some women used get a twig of mountain ash and put it under the churn on May Day and so get all the butter from her neighbours churn, on condition that she said she wanted the butter from her neighbours churn while making her own.

-Mrs. Butler, Co. Mayo

While I don't condone butter theft, Bealtaine seems to be the right time to do it. Let's look at another way to celebrate!

The May Bush

On May day morning, children get a small haw-thorn bush or at least a branch of one on which there is haw-thorn in bloom. On this bush they tie all kinds of coloured ribbons, papers, tinsel or other decorations left after the Xmas decorations till it is a gorgeous sight.

-Collected by Joan Martin

While hawthorn is the traditional tree chosen for the May bush, it's important to remember that the Irish tradition states to never ever bring hawthorn indoors.

This quote's sort of a miscellaneous one, but I thought it was interesting.

On May Night long ago the people used to leave a cake and a jug of milk on the table because they thought the Irish who were buried in America and other countries used come home on that night and visit their own home. Another old custom was to leave the doors unlocked that night. They considered it unlucky to give butter or milk way to any person on May Day as they would be giving away their luck. No stables were to be cleaned out on that day. The first person to go to the well in the morning was supposed to have luck for the rest of the year. It is not right to give money to anyone on that day. But if you get money on that day you will be getting it for the year."

-Mrs. Joyce, Co. Mayo

Ah, can't forget the ancestors. Or the diaspora! ;)

An incredibly common tradition I saw while scrolling through dúchas (I really recommend you do it yourself! They have everything!) was that milk, coals, salt, money, or really anything isn't to be given away at Bealtaine, or you'll lose something for yourself. Something supernatural about Bealtaine surpasses the Irish tradition of hospitality. This to me really highlights a theme of abundance. Welp, that's all I have for now!

🌼☀️Beannachtaí na Bealtaine oraibh!☀️🌼

#bealtaine#beltane#pagan#witchcraft#witches#irish paganism#folklore#folk witch#paganism#irish folklore#witchyvibes#pagan witch#witch community#witch tips#witchcraft 101#folk magic#wheel of the year

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's blog is on the pagan holiday Beltane on 5-1-21 BLESSED BELTANE!

🌳👑🌿🔥🙌🍄🌖🌌🌼🦋🌻🌸💐

Beltane

Beltane or Beltain (/ˈbɛl.teɪn/) is the Gaelic May Day festival. Most commonly it is held on 1 May, or about halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. In Irish the name for the festival day is Lá Bealtaine ([l̪ˠaː ˈbʲal̪ˠt̪ˠənʲə]), in Scottish Gaelic Là Bealltainn ([l̪ˠaː ˈpjaul̪ˠt̪ɪɲ]) and in Manx Gaelic Laa Boaltinn/Boaldyn. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals—along with Samhain, Imbolc and Lughnasadh—and is similar to the Welsh Calan Mai.

Also calledLá Bealtaine (Irish)

Là Bealltainn (Scottish Gaelic)

Laa Boaltinn/Boaldyn (Manx)[1]

Beltaine (French)

Beltain; Beltine; Beltany[2][3]Observed byHistorically: Gaels

Today: Irish people, Scottish people, Manx people, Galician people, Wiccans, and Celtic neopagansTypeCultural

Pagan (Celtic polytheism, Celtic neopaganism, Wicca)SignificanceBeginning of summerCelebrationslighting bonfires, decorating homes with May flowers, making May bushes, visiting holy wells, feastingDate1 May[4]

(or 1 November in the S. Hemisphere)FrequencyannualRelated toMay Day, Calan Mai, Walpurgis Night

Beltane is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature and is associated with important events in Irish mythology. Also known as Cétshamhain ("first of summer"), it marked the beginning of summer and it was when cattle were driven out to the summer pastures. Rituals were performed to protect the cattle, crops and people, and to encourage growth. Special bonfires were kindled, and their flames, smoke and ashes were deemed to have protective powers. The people and their cattle would walk around or between bonfires, and sometimes leap over the flames or embers. All household fires would be doused and then re-lit from the Beltane bonfire. These gatherings would be accompanied by a feast, and some of the food and drink would be offered to the aos sí. Doors, windows, byres and livestock would be decorated with yellow May flowers, perhaps because they evoked fire. In parts of Ireland, people would make a May Bush: typically a thorn bush or branch decorated with flowers, ribbons, bright shells and rushlights. Holy wells were also visited, while Beltane dew was thought to bring beauty and maintain youthfulness. Many of these customs were part of May Day or Midsummer festivals in other parts of Great Britain and Europe.

Beltane celebrations had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. Since the late 20th century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Beltane or a related festival as a religious holiday. Neopagans in the Southern Hemisphere celebrate Beltane on or around 1 November.

Historic Beltane customs

Beltane was one of four Gaelic seasonal festivals: Samhain (~1 November), Imbolc (~1 February), Beltane (~1 May), and Lughnasadh (~1 August). Beltane marked the beginning of the pastoral summer season, when livestock were driven out to the summer pastures. Rituals were held at that time to protect them from harm, both natural and supernatural, and this mainly involved the "symbolic use of fire". There were also rituals to protect crops, dairy products and people, and to encourage growth. The aos sí (often referred to as spirits or fairies) were thought to be especially active at Beltane (as at Samhain) and the goal of many Beltane rituals was to appease them. Most scholars see the aos sí as remnants of the pagan gods and nature spirits. Beltane was a "spring time festival of optimism" during which "fertility ritual again was important, perhaps connecting with the waxing power of the sun".

Before the modern era

Beltane (the beginning of summer) and Samhain (the beginning of winter) are thought to have been the most important of the four Gaelic festivals. Sir James George Frazer wrote in The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion that the times of Beltane and Samhain are of little importance to European crop-growers, but of great importance to herdsmen. Thus, he suggests that halving the year at 1 May and 1 November dates from a time when the Celts were mainly a pastoral people, dependent on their herds.

The earliest mention of Beltane is in Old Irish literature from Gaelic Ireland. According to the early medieval texts Sanas Cormaic (written by Cormac mac Cuilennáin) and Tochmarc Emire, Beltane was held on 1 May and marked the beginning of summer. The texts say that, to protect cattle from disease, the druids would make two fires "with great incantations" and drive the cattle between them.

According to 17th-century historian Geoffrey Keating, there was a great gathering at the hill of Uisneach each Beltane in medieval Ireland, where a sacrifice was made to a god named Beil. Keating wrote that two bonfires would be lit in every district of Ireland, and cattle would be driven between them to protect them from disease. There is no reference to such a gathering in the annals, but the medieval Dindsenchas includes a tale of a hero lighting a holy fire on Uisneach that blazed for seven years. Ronald Hutton writes that this may "preserve a tradition of Beltane ceremonies there", but adds "Keating or his source may simply have conflated this legend with the information in Sanas Chormaic to produce a piece of pseudo-history. Nevertheless, excavations at Uisneach in the 20th century found evidence of large fires and charred bones, showing it to have been ritually significant.

Beltane is also mentioned in medieval Scottish literature. An early reference is found in the poem 'Peblis to the Play', contained in the Maitland Manuscripts of 15th- and 16th-century Scots poetry, which describes the celebration in the town of Peebles.

Modern era

From the late 18th century to the mid 20th century, many accounts of Beltane customs were recorded by folklorists and other writers. For example John Jamieson, in his Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language (1808) describes some of the Beltane customs which persisted in the 18th and early 19th centuries in parts of Scotland, which he noted were beginning to die out. In the 19th century, folklorist Alexander Carmichael (1832–1912), collected the Gaellic song Am Beannachadh Bealltain (The Beltane Blessing) in his Carmina Gadelica, which he heard from a crofter in South Uist. The first two verses were sung as follows:

Beannaich, a Thrianailt fhioir nach gann, (Bless, O Threefold true and bountiful,)

Mi fein, mo cheile agus mo chlann, (Myself, my spouse and my children,)

Mo chlann mhaoth's am mathair chaomh 'n an ceann, (My tender children and their beloved mother at their head,)

Air chlar chubhr nan raon, air airidh chaon nam beann, (On the fragrant plain, at the gay mountain sheiling,)

Air chlar chubhr nan raon, air airidh chaon nam beam. (On the fragrant plain, at the gay mountain sheiling.)

Gach ni na m' fhardaich, no ta 'na m' shealbh, (Everything within my dwelling or in my possession,)

Gach buar is barr, gach tan is tealbh, (All kine and crops, all flocks and corn,)

Bho Oidhche Shamhna chon Oidhche Bheallt, (From Hallow Eve to Beltane Eve,)

Piseach maith, agus beannachd mallt, (With goodly progress and gentle blessing,)

Bho mhuir, gu muir, agus bun gach allt, (From sea to sea, and every river mouth,)

Bho thonn gu tonn, agus bonn gach steallt. (From wave to wave, and base of waterfall.)[18]

Bonfires

A Beltane bonfire at Butser Ancient Farm

Bonfires continued to be a key part of the festival in the modern era. All hearth fires and candles would be doused before the bonfire was lit, generally on a mountain or hill. Ronald Hutton writes that "To increase the potency of the holy flames, in Britain at least they were often kindled by the most primitive of all means, of friction between wood." In the 19th century, for example, John Ramsay described Scottish Highlanders kindling a need-fire or force-fire at Beltane. Such a fire was deemed sacred. In the 19th century, the ritual of driving cattle between two fires—as described in Sanas Cormaic almost 1000 years before—was still practised across most of Ireland and in parts of Scotland. Sometimes the cattle would be driven "around" a bonfire or be made to leap over flames or embers. The people themselves would do likewise. In the Isle of Man, people ensured that the smoke blew over them and their cattle. When the bonfire had died down, people would daub themselves with its ashes and sprinkle it over their crops and livestock. Burning torches from the bonfire would be taken home, where they would be carried around the house or boundary of the farmstead and would be used to re-light the hearth. From these rituals, it is clear that the fire was seen as having protective powers. Similar rituals were part of May Day, Midsummer or Easter customs in other parts of the British Isles and mainland Europe. According to Frazer, the fire rituals are a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic. According to one theory, they were meant to mimic the Sun and to "ensure a needful supply of sunshine for men, animals, and plants". According to another, they were meant to symbolically "burn up and destroy all harmful influences".

Food was also cooked at the bonfire and there were rituals involving it. Alexander Carmichael wrote that there was a feast featuring lamb, and that formerly this lamb was sacrificed. In 1769, Thomas Pennant wrote that, in Perthshire, a caudle made from eggs, butter, oatmeal and milk was cooked on the bonfire. Some of the mixture was poured on the ground as a libation. Everyone present would then take an oatmeal cake, called the bannoch Bealltainn or "Beltane bannock". A bit of it was offered to the spirits to protect their livestock (one bit to protect the horses, one bit to protect the sheep, and so forth) and a bit was offered to each of the animals that might harm their livestock (one to the fox, one to the eagle, and so forth). Afterwards, they would drink the caudle.

According to 18th century writers, in parts of Scotland there was another ritual involving the oatmeal cake. The cake would be cut and one of the slices marked with charcoal. The slices would then be put in a bonnet and everyone would take one out while blindfolded. According to one writer, whoever got the marked piece would have to leap through the fire three times. According to another, those present would pretend to throw them into the fire and, for some time afterwards, they would speak of them as if they were dead. This "may embody a memory of actual human sacrifice", or it may have always been symbolic. A similar ritual (i.e. of pretending to burn someone in the fire) was practised at spring and summer bonfire festivals in other parts of Europe.

Flowers and May Bushes

A flowering hawthorn

Yellow flowers such as primrose, rowan, hawthorn, gorse, hazel, and marsh marigold were placed at doorways and windows in 19th century Ireland, Scotland and Mann. Sometimes loose flowers were strewn at the doors and windows and sometimes they were made into bouquets, garlands or crosses and fastened to them. They would also be fastened to cows and equipment for milking and butter making. It is likely that such flowers were used because they evoked fire. Similar May Day customs are found across Europe.

The May Bush and May Bough was popular in parts of Ireland until the late 19th century. This was a small tree or branch—typically hawthorn, rowan, holly or sycamore—decorated with bright flowers, ribbons, painted shells, and so forth. The tree would either be decorated where it stood, or branches would be decorated and placed inside or outside the house. It may also be decorated with candles or rushlights. Sometimes a May Bush would be paraded through the town. In parts of southern Ireland, gold and silver hurling balls known as May Balls would be hung on these May Bushes and handed out to children or given to the winners of a hurling match. In Dublin and Belfast, May Bushes were brought into town from the countryside and decorated by the whole neighbourhood. Each neighbourhood vied for the most handsome tree and, sometimes, residents of one would try to steal the May Bush of another. This led to the May Bush being outlawed in Victorian times. In some places, it was customary to dance around the May Bush, and at the end of the festivities it may be burnt in the bonfire.

Thorn trees were seen as special trees and were associated with the aos sí. The custom of decorating a May Bush or May Tree was found in many parts of Europe. Frazer believes that such customs are a relic of tree worship and writes: "The intention of these customs is to bring home to the village, and to each house, the blessings which the tree-spirit has in its power to bestow."Emyr Estyn Evans suggests that the May Bush custom may have come to Ireland from England, because it seemed to be found in areas with strong English influence and because the Irish saw it as unlucky to damage certain thorn trees. However, "lucky" and "unlucky" trees varied by region, and it has been suggested that Beltane was the only time when cutting thorn trees was allowed. The practice of bedecking a May Bush with flowers, ribbons, garlands and bright shells is found among the Gaelic diaspora, most notably in Newfoundland, and in some Easter traditions on the East Coast of the United States.

Other customs

Holy wells were often visited at Beltane, and at the other Gaelic festivals of Imbolc and Lughnasadh. Visitors to holy wells would pray for health while walking sunwise (moving from east to west) around the well. They would then leave offerings; typically coins or clooties (see clootie well). The first water drawn from a well on Beltane was seen as being especially potent, as was Beltane morning dew. At dawn on Beltane, maidens would roll in the dew or wash their faces with it. It would also be collected in a jar, left in the sunlight, and then filtered. The dew was thought to increase sexual attractiveness, maintain youthfulness, and help with skin ailments.

People also took steps specifically to ward-off or appease the aos sí. Food was left or milk poured at the doorstep or places associated with the aos sí, such as 'fairy trees', as an offering. In Ireland, cattle would be brought to 'fairy forts', where a small amount of their blood would be collected. The owners would then pour it into the earth with prayers for the herd's safety. Sometimes the blood would be left to dry and then be burnt. It was thought that dairy products were especially at risk from harmful spirits. To protect farm produce and encourage fertility, farmers would lead a procession around the boundaries of their farm. They would "carry with them seeds of grain, implements of husbandry, the first well water, and the herb vervain (or rowan as a substitute). The procession generally stopped at the four cardinal points of the compass, beginning in the east, and rituals were performed in each of the four directions".

The festival persisted widely up until the 1950s, and in some places the celebration of Beltane continues today.

As a festival, Beltane had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. In Ireland, Beltane fires were common until the mid 20th century, but the custom seems to have lasted to the present day only in County Limerick (especially in Limerick itself) and in Arklow, County Wicklow. However, the custom has been revived in some parts of the country. Some cultural groups have sought to revive the custom at Uisneach and perhaps at the Hill of Tara. The lighting of a community Beltane fire from which each hearth fire is then relit is observed today in some parts of the Gaelic diaspora, though in most of these cases it is a cultural revival rather than an unbroken survival of the ancient tradition. In some areas of Newfoundland, the custom of decorating the May Bush is also still extant. The town of Peebles in the Scottish Borders holds a traditional week-long Beltane Fair every year in June, when a local girl is crowned Beltane Queen on the steps of the parish church. Like other Borders festivals, it incorporates a Common Riding.

Since 1988, a Beltane Fire Festival has been held every year during the night of 30 April on Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. While inspired by traditional Beltane, this festival is a modern arts and cultural event which incorporates myth and drama from a variety of world cultures and diverse literary sources. Two central figures of the Bel Fire procession and performance are the May Queen and the Green Man.

Neo-Paganism

Beltane and Beltane-based festivals are held by some Neopagans. As there are many kinds of Neopaganism, their Beltane celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible. Other Neopagans base their celebrations on many sources, the Gaelic festival being only one of them.

Neopagans usually celebrate Beltane on 30 April – 1 May in the Northern Hemisphere and 31 October – 1 November in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sunset. Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the spring equinox and summer solstice (or the full moon nearest this point). In the Northern Hemisphere, this midpoint is when the ecliptic longitude of the Sun reaches 45 degrees.

Celtic Reconstructionist

Celtic Reconstructionists strive to reconstruct the pre-Christian religions of the Celts. Their religious practices are based on research and historical accounts, but may be modified slightly to suit modern life. They avoid modern syncretism and eclecticism (i.e. combining practises from unrelated cultures).

Celtic Reconstructionists usually celebrate Lá Bealtaine when the local hawthorn trees are in bloom. Many observe the traditional bonfire rites, to whatever extent this is feasible where they live. This may involve passing themselves and their pets or livestock between two bonfires, and bringing home a candle lit from the bonfire. If they are unable to make a bonfire or attend a bonfire ceremony, torches or candles may be used instead. They may decorate their homes with a May Bush, branches from blooming thorn trees, or equal-armed rowan crosses. Holy wells may be visited and offerings made to the spirits or deities of the wells. Traditional festival foods may also be prepared.

Wicca

Wiccans use the name Beltane or Beltain for their May Day celebrations. It is one of the yearly Sabbats of the Wheel of the Year, following Ostara and preceding Midsummer. Unlike Celtic Reconstructionism, Wicca is syncretic and melds practices from many different cultures. In general, the Wiccan Beltane is more akin to the Germanic/English May Day festival, both in its significance (focusing on fertility) and its rituals (such as maypole dancing). Some Wiccans enact a ritual union of the May Lord and May Lady.

Name

In Irish, the festival is usually called Lá Bealtaine ('day of Beltane') while the month of May is Mí Bhealtaine ("month of Beltane"). In Scottish Gaelic, the festival is Latha Bealltainn and the month is An Cèitean or a' Mhàigh. Sometimes the older Scottish Gaelic spelling Bealltuinn is used. The word Céitean comes from Cétshamain ('first of summer'), an old alternative name for the festival. The term Latha Buidhe Bealltainn (Scottish) or Lá Buidhe Bealtaine (Irish), 'the bright or yellow day of Beltane', means the first of May. In Ireland it is referred to in a common folk tale as Luan Lae Bealtaine; the first day of the week (Monday/Luan) is added to emphasise the first day of summer.

The name is anglicized as Beltane, Beltain, Beltaine, Beltine and Beltany.

Etymology

Two modern etymologies have been proposed. Beltaine could derive from a Common Celtic *belo-te(p)niâ, meaning 'bright fire'. The element *belo- might be cognate with the English word bale (as in bale-fire) meaning 'white' or 'shining'; compare Old English bǣl, and Lithuanian/Latvian baltas/balts, found in the name of the Baltic; in Slavic languages byelo or beloye also means 'white', as in Беларусь ('White Rus′' or Belarus) or Бе́лое мо́ре ('White Sea').[citation needed] Alternatively, Beltaine might stem from a Common Celtic form reconstructed as *Beltiniyā, which would be cognate with the name of the Lithuanian goddess of death Giltinė, both from an earlier *gʷel-tiōn-, formed with the Proto-Indo-European root *gʷelH- ('suffering, death'). The absence of syncope (Irish sound laws rather predict a **Beltne form) is explained by the popular belief that Beltaine was a compound of the word for 'fire', tene.

In Ó Duinnín's Irish dictionary (1904), Beltane is referred to as Céadamh(ain) which it explains is short for Céad-shamh(ain) meaning 'first (of) summer'. The dictionary also states that Dia Céadamhan is May Day and Mí Céadamhan is the month of May.

There are a number of place names in Ireland containing the word Bealtaine, indicating places where Bealtaine festivities were once held. It is often anglicised as Beltany. There are three Beltanys in County Donegal, including the Beltany stone circle, and two in County Tyrone. In County Armagh there is a place called Tamnaghvelton/Tamhnach Bhealtaine ('the Beltane field'). Lisbalting/Lios Bealtaine ('the Beltane ringfort') is in County Tipperary, while Glasheennabaultina/Glaisín na Bealtaine ('the Beltane stream') is the name of a stream joining the River Galey in County Limerick.

Source: Wikipedia

I hope you've enjoyed this blog more to follow soon,

Blessed be,

Culture Calypso's Blog 🌻🌸💐

#beltaine#paganism#pagan holidays#history#my blogs#faecore#irish culture#tuatha de danann#spirituality#summer

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Paganism & Pagan Holidays: Happy Beltane/May Day 2018!!

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beltane

Beltane (/ˈbɛl.teɪn/) is the anglicised name for the Gaelic May Day festival. Most commonly it is held on 1 May (1 November in the Southern Hemisphere), or about halfway between the spring equinox and the summer solstice. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Irish the name for the festival day is Lá Bealtaine ([l̪ˠaː ˈbʲal̪ˠt̪ˠənʲə]), in Scottish Gaelic Là Bealltainn ([l̪ˠa: ˈpjaul̪ˠt̪ˠɪɲ]) and in Manx Gaelic Laa Boaltinn/Boaldyn. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals—along with Samhain, Imbolc and Lughnasadh—and is similar to the Welsh Calan Mai.

Beltane is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature, and it is associated with important events in Irish mythology. It marked the beginning of summer and was when cattle were driven out to the summer pastures. Rituals were performed to protect the cattle, crops and people, and to encourage growth. Special bonfires were kindled, and their flames, smoke and ashes were deemed to have protective powers. The people and their cattle would walk around the bonfire or between two bonfires, and sometimes leap over the flames or embers. All household fires would be doused and then re-lit from the Beltane bonfire. These gatherings would be accompanied by a feast, and some of the food and drink would be offered to the aos sí. Doors, windows, byres and the cattle themselves would be decorated with yellow May flowers, perhaps because they evoked fire. In parts of Ireland, people would make a May Bush: a thorn bush decorated with flowers, ribbons and bright shells. Holy wells were also visited, while Beltane dew was thought to bring beauty and maintain youthfulness. Many of these customs were part of May Day or Midsummer festivals in other parts of Great Britain and Europe.

Beltane celebrations had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. Since the late 20th century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Beltane, or something based on it, as a religious holiday. Neopagans in the Southern Hemisphere often celebrate Beltane at the other end of the year (around 1 November).

Before the modern era

Beltane (the beginning of summer) and Samhain (the beginning of winter) are thought to have been the most important of the four Gaelic festivals. Sir James George Frazer wrote in The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion that the times of Beltane and Samhain are of little importance to European crop-growers, but of great importance to herdsmen. Thus, he suggests that halving the year at 1 May and 1 November dates from a time when the Celts were mainly a pastoral people, dependent on their herds.

The earliest mention of Beltane is in Old Irish literature from Gaelic Ireland. According to the early medieval texts Sanas Cormaic and Tochmarc Emire, Beltane was held on 1 May and marked the beginning of summer. The texts say that, to protect cattle from disease, the druids would make two fires "with great incantations" and drive the cattle between them.

According to 17th-century historian Geoffrey Keating, there was a great gathering at the hill of Uisneach each Beltane in medieval Ireland, where a sacrifice was made to a god named Beil. Keating wrote that two bonfires would be lit in every district of Ireland, and cattle would be driven between them to protect them from disease. There is no reference to such a gathering in the annals, but the medieval Dindsenchas includes a tale of a hero lighting a holy fire on Uisneach that blazed for seven years. Ronald Hutton writes that this may "preserve a tradition of Beltane ceremonies there", but adds "Keating or his source may simply have conflated this legend with the information in Sanas Chormaic to produce a piece of pseudo-history." Nevertheless, excavations at Uisneach in the 20th century found evidence of large fires and charred bones, showing it to have been ritually significant.

Modern era

From the late 18th century to the mid 20th century, many accounts of Beltane customs were recorded by folklorists and other writers.

Bonfires

Bonfires continued to be a key part of the festival in the modern era. All hearth fires and candles would be doused before the bonfire was lit, generally on a mountain or hill. Ronald Hutton writes that "To increase the potency of the holy flames, in Britain at least they were often kindled by the most primitive of all means, of friction between wood." In the 19th century, for example, John Ramsay described Scottish Highlanders kindling a need-fire or force-fire at Beltane. Such a fire was deemed sacred. In the 19th century, the ritual of driving cattle between two fires—as described in Sanas Cormaic almost 1000 years before—was still practised across most of Ireland and in parts of Scotland. Sometimes the cattle would be driven "around" a bonfire or be made to leap over flames or embers. The people themselves would do likewise. In the Isle of Man, people ensured that the smoke blew over them and their cattle.[6] When the bonfire had died down, people would daub themselves with its ashes and sprinkle it over their crops and livestock. Burning torches from the bonfire would be taken home, where they would be carried around the house or boundary of the farmstead and would be used to re-light the hearth. From these rituals, it is clear that the fire was seen as having protective powers. Similar rituals were part of May Day, Midsummer or Easter customs in other parts of the British Isles and mainland Europe. According to Frazer, the fire rituals are a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic. According to one theory, they were meant to mimic the Sun and to "ensure a needful supply of sunshine for men, animals, and plants". According to another, they were meant to symbolically "burn up and destroy all harmful influences".

Food was also cooked at the bonfire and there were rituals involving it. Alexander Carmichael wrote that there was a feast featuring lamb, and that formerly this lamb was sacrificed. In 1769, Thomas Pennant wrote that, in Perthshire, a caudle made from eggs, butter, oatmeal and milk was cooked on the bonfire. Some of the mixture was poured on the ground as a libation. Everyone present would then take an oatmeal cake, called the bannoch Bealltainn or "Beltane bannock". A bit of it was offered to the spirits to protect their livestock (one bit to protect the horses, one bit to protect the sheep, and so forth) and a bit was offered to each of the animals that might harm their livestock (one to the fox, one to the eagle, and so forth). Afterwards, they would drink the caudle.

According to 18th century writers, in parts of Scotland there was another ritual involving the oatmeal cake. The cake would be cut and one of the slices marked with charcoal. The slices would then be put in a bonnet and everyone would take one out while blindfolded. According to one writer, whoever got the marked piece would have to leap through the fire three times. According to another, those present would pretend to throw him into the fire and, for some time afterwards, they would speak of him as if he were dead. This "may embody a memory of actual human sacrifice", or it may have always been symbolic. A similar ritual (i.e. of pretending to burn someone in the fire) was practised at spring and summer bonfire festivals in other parts of Europe. Flowers and May Bushes

Yellow flowers such as primrose, rowan, hawthorn, gorse, hazel, and marsh marigold were placed at doorways and windows in 19th century Ireland, Scotland and Mann. Sometimes loose flowers were strewn at the doors and windows and sometimes they were made into bouquets, garlands or crosses and fastened to them. They would also be fastened to cows and equipment for milking and butter making. It is likely that such flowers were used because they evoked fire.[5] Similar May Day customs are found across Europe.

The May Bush was popular in parts of Ireland until the late 19th century. This was a small tree or branch—typically hawthorn, rowan or sycamore—decorated with bright flowers, ribbons, painted shells, and so forth. There were household May Bushes (which would be placed outside each house) and communal May Bushes (which would be set in a public spot or paraded around the neighbourhood). In Dublin and Belfast, May Bushes were brought into town from the countryside and decorated by the whole neighbourhood. Each neighbourhood vied for the most handsome tree and, sometimes, residents of one would try to steal the May Bush of another. This led to the May Bush being outlawed in Victorian times. In some places, it was customary to dance around the May Bush, and at the end of the festivities it may be burnt in the bonfire. Some, however, were left in place for a month. Thorn trees were seen as special trees and were associated with the aos sí. The custom of decorating a May Bush or May Tree was found in many parts of Europe. Frazer believes that such customs are a relic of tree worship and writes: "The intention of these customs is to bring home to the village, and to each house, the blessings which the tree-spirit has in its power to bestow." Emyr Estyn Evans suggests that the May Bush custom may have come to Ireland from England, because it seemed to be found in areas with strong English influence and because the Irish saw it as unlucky to damage certain thorn trees. However, "lucky" and "unlucky" trees varied by region, and it has been suggested that Beltane was the only time when cutting thorn trees was allowed. The practice of bedecking a May Bush with flowers, ribbons, garlands and bright shells is found among the Gaelic diaspora, most notably in Newfoundland, and in some Easter traditions on the East Coast of the United States.

Other customs

Holy wells were often visited at Beltane, and at the other Gaelic festivals of Imbolc and Lughnasadh. Visitors to holy wells would pray for health while walking sunwise (moving from east to west) around the well. They would then leave offerings; typically coins or clooties (see clootie well).[14] The first water drawn from a well on Beltane was seen as being especially potent, as was Beltane morning dew. At dawn on Beltane, maidens would roll in the dew or wash their faces with it. It would also be collected in a jar, left in the sunlight, and then filtered. The dew was thought to increase sexual attractiveness, maintain youthfulness, and help with skin ailments.

People also took steps specifically to ward-off or appease the aos sí. Food was left or milk poured at the doorstep or places associated with the aos sí, such as 'fairy trees', as an offering. In Ireland, cattle would be brought to 'fairy forts', where a small amount of their blood would be collected. The owners would then pour it into the earth with prayers for the herd's safety. Sometimes the blood would be left to dry and then be burnt. It was thought that dairy products were especially at risk from harmful spirits. To protect farm produce and encourage fertility, farmers would lead a procession around the boundaries of their farm. They would "carry with them seeds of grain, implements of husbandry, the first well water, and the herb vervain (or rowan as a substitute). The procession generally stopped at the four cardinal points of the compass, beginning in the east, and rituals were performed in each of the four directions".

The festival persisted widely up until the 1950s, and in some places the celebration of Beltane continues today.

Revival

As a festival, Beltane had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. In Ireland, Beltane fires were common until the mid 20th century, but the custom seems to have lasted to the present day only in County Limerick (especially in Limerick itself) and in Arklow, County Wicklow. However, the custom has been revived in some parts of the country. Some cultural groups have sought to revive the custom at Uisneach and perhaps at the Hill of Tara. The lighting of a community Beltane fire from which each hearth fire is then relit is observed today in some parts of the Gaelic diaspora, though in most of these cases it is a cultural revival rather than an unbroken survival of the ancient tradition. In some areas of Newfoundland, the custom of decorating the May Bush is also still extant. The town of Peebles in the Scottish Borders holds a traditional week-long Beltane Fair every year in June, when a local girl is crowned Beltane Queen on the steps of the parish church. Like other Borders festivals, it incorporates a Common Riding.

Since 1988, a Beltane Fire Festival has been held every year during the night of 30 April on Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. While inspired by traditional Beltane, this festival is a modern arts and cultural event which incorporates myth and drama from a variety of world cultures and diverse literary sources.

Neo-Paganism

Beltane and Beltane-based festivals are held by some Neopagans. As there are many kinds of Neopaganism, their Beltane celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible. Other Neopagans base their celebrations on many sources, the Gaelic festival being only one of them.

Neopagans usually celebrate Beltane on 30 April – 1 May in the Northern Hemisphere and 31 October – 1 November in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sunset. Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the spring equinox and summer solstice (or the full moon nearest this point). In the Northern Hemisphere, this midpoint is when the ecliptic longitude of the Sun reaches 45 degrees.[44] In 2014, this was on 5 May.

Celtic Reconstructionist

Celtic Reconstructionists strive to reconstruct the pre-Christian religions of the Celts. Their religious practices are based on research and historical accounts, but may be modified slightly to suit modern life. They avoid modern syncretism and eclecticism (i.e. combining practises from unrelated cultures).

Celtic Reconstructionists usually celebrate Lá Bealtaine when the local hawthorn trees are in bloom. Many observe the traditional bonfire rites, to whatever extent this is feasible where they live. This may involve passing themselves and their pets or livestock between two bonfires, and bringing home a candle lit from the bonfire. If they are unable to make a bonfire or attend a bonfire ceremony, torches or candles may be used instead. They may decorate their homes with a May Bush, branches from blooming thorn trees, or equal-armed rowan crosses. Holy wells may be visited and offerings made to the spirits or deities of the wells. Traditional festival foods may also be prepared.

Wicca

Wiccans use the name Beltane or Beltain for their May Day celebrations. It is one of the yearly Sabbats of the Wheel of the Year, following Ostara and preceding Midsummer. Unlike Celtic Reconstructionism, Wicca is syncretic and melds practices from many different cultures. In general, the Wiccan Beltane is more akin to the Germanic/English May Day festival, both in its significance (focusing on fertility) and its rituals (such as maypole dancing). Some Wiccans enact a ritual union of the May Lord and May Lady.

Name

In Irish, the festival is usually called Lá Bealtaine ("day of Beltane") while the month of May is Mí Bhealtaine ("month of Beltane"). In Scottish Gaelic, the month is called (An) Cèitean or a' Mhàigh, and the festival is Latha Bealltainn. Sometimes the older Scottish Gaelic spelling Bealltuinn is used. The word Céitean comes from Céad Shamhain, an old alternative name for the festival.

In modern Scottish Gaelic, Latha Buidhe Bealltainn or Là Buidhe Bealltainn ("the yellow day of Beltane") is used to describe the first day of May. This term Lá Buidhe Bealtaine is also used in Irish and is translated as "Bright May Day". In Ireland it is referred to in a common folk tale as Luan Lae Bealtaine; the first day of the week (Monday/Luan) is added to emphasise the first day of summer.

Etymology

Since the early 20th century it has been commonly accepted that Old Irish Beltaine is derived from a Common Celtic *belo-te(p)niâ, meaning "bright fire". The element *belo- might be cognate with the English word bale (as in bale-fire) meaning "white" or "shining"; compare Old English bael, and Lithuanian/Latvian baltas/balts, found in the name of the Baltic; in Slavic languages byelo or beloye also means "white", as in Беларусь (White Russia or Belarus) or Бе́лое мо́ре (White Sea). A more recent etymology by Xavier Delamarre would derive it from a Common Celtic *Beltinijā, cognate with the name of the Lithuanian goddess of death Giltinė, the root of both being Proto-Indo-European *gʷelH- ("suffering, death").

In Ó Duinnín's Irish dictionary (1904), Beltane is referred to as Céadamh(ain) which it explains is short for Céad-shamh(ain) meaning "first (of) summer". The dictionary also states that Dia Céadamhan is May Day and Mí Céadamhan is the month of May.

Toponymy

There are a number of place names in Ireland containing the word Bealtaine, indicating places where Bealtaine festivities were once held. It is often anglicised as Beltany. There are three Beltanys in County Donegal, including the Beltany stone circle, and two in County Tyrone. In County Armagh there is a place called Tamnaghvelton/Tamhnach Bhealtaine ("the Beltane field"). Lisbalting/Lios Bealtaine ("the Beltane ringfort") is in County Tipperary, while Glasheennabaultina/Glaisín na Bealtaine ("the Beltane stream") is the name of a stream joining the River Galey in County Limerick.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Beltane Bale Fire Tradition

by Patti Wigington

Updated February 16, 2018

One of the hallmarks of any Beltane celebration is the bonfire, or the Bale Fire (this can be spelled a number of ways, including Beal Fire and Bel Fire). This tradition has its roots in early Ireland. According to legend, each year at Beltane, the tribal leaders would send a representative to the hill of Uisneach, where a great bonfire was lit. These representatives would each light a torch, and carry it back to their home villages.

Once the fire reached the village, everyone would light a torch to take into their houses and use to light their hearths. This way, the fire of Ireland was spread from one central source throughout the entire country.

In Scotland, traditions were slightly different, as the Bale Fire was used as a protection and purification of the herd. Two fires were lit, and cattle were driven between the pair. This was also thought to bring good fortune to the herders and farmers.

In some places, the Bale Fire was used as a signal beacon. In Dartmoor, England, there is a hill known as the Cosdon Beacon. During the medieval period, beacon fires were lit at the top of the hill, which -- thanks to its height and location -- was the perfect spot for ultimate visibility. The hill is located in an area that allows, on a clear day, a view into North Devon, parts of Cornwall, and Somerset.

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines the Bale Fire (or balefire) as a funeral fire and describes the etymology of the word as being from the Old English, with bael meaning funeral, and fyr as fire.

However, the use of the word has sort of fallen out of favor as a term for a funeral pyre.

The Bale Fire Today

Today, many modern Pagans re-create the use of the Bale Fire as part of our Beltane celebrations -- in fact, it is likely that the word “Beltane” has evolved from this tradition. The fire is more than a big pile of logs and some flame.

It is a place where the entire community gathers around -- a place of music and magic and dancing and lovemaking.

To celebrate Beltane with a fire, you may want to light the fire on May Eve (the last night of April) and allow it to burn until the sun goes down on May 1. Traditionally, the balefire was lit with a bundle made from nine different types of wood and wrapped with colorful ribbons -- why not incorporate this into your own rituals? Once the fire was blazing, a piece of smoldering wood was taken to each home in the village, to ensure fertility throughout the summer months. While it may not be practical for each of your friends to transport a piece of smoldering wood home in their cars, you can send a bit of symbolic unburned wood from the fire home with them, and they can burn it at their own hearths. Be sure to read the Beltane bonfire ritual if you’re planning a group ceremony.

Basic Bonfire Safety

If you're holding a bonfire this year at Beltane, great. Follow a few basic safety tips, to make sure everyone has a good time and no one gets hurt.

First of all, make sure your bonfire is set up on a stable surface. The ground should be level, and in a safe location -- this means keep it away from buildings or flammable materials.

Assign fire tenders to be in charge of the blaze, and make sure they are the only ones who add anything to the bonfire. Be sure to have water and sand nearby, in case the fire needs to be extinguished in a hurry. A rake and shovel can come in handy as well.

Be sure to check weather conditions before you start your fire -- if it's windy, hold off. Nothing will ruin a ritual faster than having to dodge embers -- or worse yet, having those embers start a brushfire that can't be contained.

Don't add combustible items to the fire. Don't throw in batteries, fireworks, or other items that can cause a hazard. In addition, a ritual fire should not be a place where you throw your trash. Before adding anything to a ritual bonfire, be sure to check with the fire tenders.

Finally, if there are children or pets at your event, make sure they give the fire a wide berth.

Parents and pet owners should be cautioned if their child or their furry friend gets too close.

https://www.thoughtco.com/the-beltane-bale-fire-2561632

#witch#witchcraft for beginners#witchcraft#wicca#wicca for beginners#fire#balefire#beltane#bonfire#magick#ritual#fire safety#witch wisdom#vocabulary#pagan#history#traditional witchcraft

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CMP Special 19 Damh the Bard Interview

We chat with the Mythic Folk Musician and Druid, Damh the Bard

This is our first interview and we are lucky to be able to interview the famous Celtic Folk musician, Damh the Bard, and his wife, the multi-talented Artist Cerri Lee. Links to their websites and their work can be found below in the Show-notes. We also bring you an amazing competition for Damh's latest album, Tales from the Cowman as well as some astounding news about the revival of a national tradition in Ireland - the Festival of the Fires taking place on Beltane.

Full Show-notes, with all credits, can be found on our main Website at http://celticmythpodshow.com/bardinterview

Running Order:

Intro 0:42

News & Views 1:25

The Festival of the Fires 1:58

Twa Corbies by Damh the Bard 04:15

Damh the Bard Interview 7:54

Blodeuwedd by Damh the Bard 29:24

The Cauldron Born by Damh the Bard 45:51

Pagan Spirit Gathering 1:02:19

Cerri Lee 1:05:48

Grimspound by Damh the Bard 1:17:57

Competition 1:23:00

Spirit of Albion by Damh the Bard 1:24:19

Out-takes 1:28:44

We hope you enjoy it!

Gary & Ruthie x x x

Released: 30th April 2010, 1h 31m

It's always great to hear from you! Email [email protected], or leave us a message using Speakpipe

The Festival of the Fires

Our fabulous news item introduces the Festival of Fires which is a resuscitation of the ancient fires of Tara that were lit on the Hill of Uisneach and the taken from County to County to ignite all of the fires in Ireland. Originally known as Bealtaine, the summertime festival was an important fixture on the worldwide calendar, attracting attendees from the four corners of the ancient world. Having not being officially celebrated in hundreds of years the festival is to return, rising from the ashes of the Bealtaine name as Festival of the Fires. It promises to be an event unlike anything ever witnessed in modern times - an iconic national celebration to truly ignite the summer. Created through the alchemy of ceremony, heritage, music, theatre, literature, arts, crafts, poetry, holistic health and sustainability.

Festival of the Fires will feature the collective talents of hundreds of participants drawn from all over Ireland and the world, gathering at the exact centre-point of Ireland to celebrate the onset of summer.

One of the ceremonial highlights of the festival will be the lighting of a national fire, ignited first on the summit of Uisneach and then carried to hilltops in every one of Ireland's 32 counties. In ancient times, this sacred Uisneach fire was the catalyst for coast-to-coast celebrations with festivals and gatherings taking place in the fire sites, and in the communities below.

You can find out more about the festival on the website at http://festivalofthefires.com/.

Twa Corbies

by Damh the Bard

A classic folk track, the Twa Corbies or 'two crows', given the Damh the Bard magical treatment for the new Crowman album.

Damh the Bard Interview

(Pronounced 'Dave')

Damh is a musical storyteller who works within the world of myth that cannot be proved; where the Faerie really do dance on Midsummer's Eve, where the trees talk, and the Hollow Hills take you into the realms of Annwn. Where the Goddess rides her horse, guiding you to magic, and the Horned God of old calls us from the shadows of the Greenwood. [source]

Damh is also the relaxed voice behind Druidcast, the podcast from the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids (OBOD).

You can find out more about Damh and his work on his website at paganmusic.co.uk or on our Contributor Page.

Blodeuwedd

by Damh the Bard

The tale of Blodeuwedd taken by Damh from the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi.

The Cauldon Born

by Damh the Bard

The Story of Cerridwen and how we are all, in a fashion, Cerridwen's Children, or "the Cauldron Born".

Pagan Spirit Gathering

The Pagan Spirit Gathering (PSG) is one of America's oldest and largest Nature Spirituality festivals. Since its inception in 1980, PSG has been bringing together hundreds of people from throughout the United States, plus other countries, to create community, celebrate Summer Solstice, and commune with Nature in a sacred environment. Sponsored by Circle Sanctuary, PSG is open to long-time practitioners as well as newcomers of a wide range of Nature religion traditions, including Wiccan, Contemporary Pagan, Druidic, Heathen, Celtic, Baltic, Greco-Roman, Isian, Shamanic, Hermetic, Animistic, Egyptian, Native American, Afro-Carribean, Taoist, Pantheistic, Ecofeminist, and Nature Mystic. PSG is an opportunity for personal renewal, networking, education, and cultural enrichment.

You can see their musical line-up (including Damh) or book tickets on their website.

Cerri Lee

Cerri Lee is a multi-talented visionary artist who can turn her hand to almost anything creative. She is inspired by nature, and the ancient Pagan myths and legends of many cultures, her beliefs as a modern day Druid as well as those around her. She can create anything from Rights of Passage gifts and altar pieces to wedding and birthday gifts, and will happily take on commissions. Each piece of artwork she creates is individual and can be personalised to you or your loved ones.

Her artwork has been used for album covers, featured in leading Pagan magazines, used as tattoos, and her sculptures are sent throughout the world.

Cerri is equally in her element when she is up to her elbows in clay or painting one of her fabulous pictures. She is partner to Druid musician and long-time supporter of our show, Damh the Bard and can be found supporting him at many of his performances.

You can see a gallery of Cerri's artist work on our website at Cerri's Gallery and you can find out more about Cerri and her work on her website on cerrilee.com or on our Contributor page.

Grimspound

by Damh the Bard

Grimspound is a late Bronze Age settlement high on the moor. It’s surrounded by a large fallen stone wall, and inside you can still see the remains of the roundhouses. On a beautiful day it is incredibly peaceful, but on a typical Dartmoor day, with the wind and the rain, it must have been a harsh place to live.

"I sat with my guitar inside the remains of one of the roundhouses and just began to play on the guitar – looking around, breathing in the history of the place, imagining it full of life. What kind of people lived there. A Raven called overhead, and I felt I could see torchlight on the Tors either side of me. Voices of the Ancestors singing. The Land singing. And the melody of the guitar began to take shape. A ghostly and reflective refrain."

Competition

Damh left us with a signed copy of his latest album, Tales from the Crowman, to give away as a competition prize. So, we set a competition based on Welsh Mythology for you.

Spirit of Albion

by Damh the Bard

Damh plays us his rousing anthem, a paean of praise to the land, Spirit of Albion from the album of the same name.

Get EXTRA content in the Celtic Myth Podshow App for iOS, Android & Windows

Contact Us: You can leave us a message by using the Speakpipe

Email us at: [email protected]. Facebook fan-page http://www.facebook.com/CelticMythPodshow, Twitter (@CelticMythShow) or Snapchat (@garyandruth), Pinterest (celticmythshow) or Instagram (celticmythshow)

Help Spread the Word:

Please also consider leaving us a rating, a review and subscribing in iTunes or 'Liking' our Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/CelticMythPodshow as it helps let people discover our show - thank you :)

If you've enjoyed the show, would you mind sharing it on Twitter please? Click here to post a tweet!

Ways to subscribe to the Celtic Myth Podshow:

Click here to subscribe via iTunes

Click here to subscribe via RSS

Click here to subscribe via Stitcher

Special Thanks

Diane Arkenstone The Secret Garden. See her Contributor page for details.

Kim Robertson The Hangman's Noose. See her Contributor page for details.

Jigger Time Ticks Away. See her Contributor page for details.

For our Theme Music:

The Skylark and Haghole, the brilliant Culann's Hounds. See their Contributor page for details.

Extra Special Thanks for Unrestricted Access to Wonderful Music

(in Alphabetic order)

Anne Roos Extra Special thanks go for permission to use any of her masterful music to Anne Roos. You can find out more about Anne on her website or on her Contributor page.

Caera Extra Special thanks go for permission to any of her evocative harping and Gaelic singing to Caera. You can find out more about Caera on her website or on her Contributor Page.

Celia Extra Special Thanks go for permission to use any of her wonderful music to Celia Farran. You can find out more about Celia on her website or on her Contributor Page.

Damh the Bard Extra Special thanks go to Damh the Bard for his permission to use any of his music on the Show. You can find out more about Damh (Dave) on his website or on his Contributor page.

The Dolmen Extra Special thanks also go to The Dolmen, for their permission to use any of their fantastic Celtic Folk/Rock music on the Show. You can find out more about The Dolmen on their website or on our Contributor page.

Keltoria Extra Special thanks go for permission to use any of their inspired music to Keltoria. You can find out more about Keltoria on their website or on their Contributor page.

Kevin Skinner Extra Special thanks go for permission to use any of his superb music to Kevin Skinner. You can find out more about Kevin on his website or on his Contributor page.

Phil Thornton Extra Special Thanks go for permission to use any of his astounding ambient music to the Sonic Sorcerer himself, Phil Thornton. You can find out more about Phil on his website or on his Contributor Page.

S.J. Tucker Extra Special thanks go to Sooj for her permission to use any of her superb music. You can find out more about Sooj on her website or on her Contributor page.

Spiral Dance Extra Special thanks go for permission to use Adrienne and the band to use any of their music in the show. You can find out more about Spiral Dance on their website or on their Contributor page.

We'd like to wish you 'Slán Go Foill!', which is Irish for 'Goodbye', or more literally 'Wishing you safety for a while'!

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

Eve of Bealtaine | Beltane

Eve of Bealtaine | Beltane

The Celtic Festival of Bealtaine/Beltane which marks the beginning of summer in the ancient Celtic calendar is a Cross Quarter Day, half way between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice. While the Bealtaine Festival is now associated with 1st May, the actual astronomical date is a number of days later. The festival was marked with the lighting of great bonfires that would mark a time of…

View On WordPress

#Ériu#Beltane#Beltany Stone Circle#Bonfires#Celtic Festival#Co. Donegal#Druidical ceremonies#Druids#Eve of Bealtaine#Gathering at Uisneach#Hill of Uisneach#Irish Mythology#MayDay#Quarter Days#Raphoe

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eve of Bealtaine | Beltane

Eve of Bealtaine | Beltane

The Celtic Festival of Bealtaine/Beltane which marks the beginning of summer in the ancient Celtic calendar is a Cross Quarter Day, half way between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice. While the Bealtaine Festival is now associated with 1st May, the actual astronomical date is a number of days later. The festival was marked with the lighting of great bonfires that would mark a time of…

View On WordPress

#Ériu#Beltane#Beltany Stone Circle#Bonfires#Celtic Festival#Co. Donegal#Druidical ceremonies#Druids#Eve of Bealtaine#Gathering at Uisneach#Hill of Uisneach#Irish Mythology#MayDay#Quarter Days#Raphoe

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eve of Bealtaine/Beltane

The Celtic Festival of Bealtaine/Beltane which marks the beginning of summer in the ancient Celtic calendar is a Cross Quarter Day, half way between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice. While the Bealtaine Festival is now associated with 1st May, the actual astronomical date is a number of days later. The festival was marked with the lighting of great bonfires that would mark a time of…

View On WordPress

#Ériu#Beltane#Beltany Stone Circle#Bonfires#Celtic Festival#Co. Donegal#Druidical ceremonies#Druids#Eve of Bealtaine#Gathering at Uisneach#Hill of Uisneach#Irish Mythology#MayDay#Quarter Days#Raphoe

1 note

·

View note

Text

Eve of Bealtaine/Beltane

The Celtic Festival of Bealtaine/Beltane which marks the beginning of summer in the ancient Celtic calendar is a Cross Quarter Day, half way between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice. While the Bealtaine Festival is now associated with 1st May, the actual astronomical date is a number of days later. The festival was marked with the lighting of great bonfires that would mark a time of…

View On WordPress

#Ériu#Beltane#Beltany Stone Circle#Bonfires#Celtic Festival#Co. Donegal#Druidical ceremonies#Druids#Eve of Bealtaine#Gathering at Uisneach#Hill of Uisneach#Irish Mythology#MayDay#Quarter Days#Raphoe

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eve of Bealtaine/Beltane

The Celtic Festival of Bealtaine/Beltane which marks the beginning of summer in the ancient Celtic calendar is a Cross Quarter Day, half way between the Spring Equinox and the Summer Solstice. While the Bealtaine Festival is now associated with 1st May, the actual astronomical date is a number of days later. The festival was marked with the lighting of great bonfires that would mark a time of…

View On WordPress

#Ériu#Beltane#Beltany Stone Circle#Bonfires#Celtic Festival#Co. Donegal#Druidical ceremonies#Druids#Eve of Bealtaine#Gathering at Uisneach#Hill of Uisneach#Irish Mythology#MayDay#Quarter Days#Raphoe

0 notes