#Functionalism Historicized (book)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Few Critical Books I’ve Read

Gender and Sexuality Studies

Woman and the New Race by Margaret Sanger

This book was written in the 1920s in support of birth control. An intriguing look at the history of women’s rights and the reality of Black exclusion.

The Stonewall Reader by the New York Public Library

Essays, articles, and interviews detailing the importance of the Stonewall Uprising to queer States’ history.

Trans Liberation : Beyond Pink or Blue by Leslie Feinberg

Collection of Feinberg’s speeches on the importance of Trans Liberation.

Sexuality and the Unnatural in Colonial Latin America by Zeb Tortorici

Exploration of sex and laws in Colonial Latin America under the Inquisition.

Exploring Masculinities : Identity, Inequality, Continuity and Change by C J Pascoe and Tristan Bridges

A history of masculinities in the States and how they affect our present.

Race Studies

Four Hundred Souls : A Community History of African America 1619-2019 by Ibram X Kendi and Keisha N Blain

Collection of poems and essays detailing the history of African America.

White Trash : the 400-Year Untold History of Class in America by Nancy Isenberg

Best read in conjunction with White Fragility. History of class in the States with notes on how it’s affect changed depending on gender and race.

Historicizing Race by Marius Turda

A history of how race has affected and been affected by every function of society, history, and “science”.

White Fragility : Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin D’Angelo

Discusses why race is a taboo subject in White America.

So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo

A personal experience with racism and the common questions and arguments that appear in this discussion.

Relationship Studies

Attached : The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find and Keep Love by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller

Reviews the four attachment styles and how they affect our interpersonal relationships.

1 note

·

View note

Note

What's exactly the difference between Almuten Figuris and Lord of Geniture? Which one is stronger?

I already kinda answered this here. But this particular question is very complicated, and I can't just give you a quick answer. I'll just give you some contextualization and sources for you to study. Because it's not just a question of different concepts, it's also a question of different astrologies, different philosophical and religious ideas, because they come from different times and places. Most astrologers know the William Lilly's version of the Lord of Geniture, who was an english astrologer in the 17th century. The Almuten Figuris is a medieval arabic technique, that we see in the works of Abu Ma’shar or Al-Biruni, for example. But there's also the hellenistic Oikodespotes, the Kurios, which get introduced by Porphyry, and none of the other hellenistic authors who mention those agree with him about the calculation methods.

The concepts behind those can be somewhat similar, they are all trying to theorize about a way to find the strongest and/or most influential planet in a chart, in a life, but they all have different ideas about those planets and their function in the native's destiny. Since these people are separated by so much time, space and culture, you can imagine why they think so differently. The method of the Almuten Figuris places importance on the hylegiac points (vital points, such as the sun, moon, ascendant), but Lilly's Lord of the Geniture is more about the planet with the most dignity overall and he kinda mixes some of the hellenistic ideas. This is obviously due to philosophical and religious differences in their understanding of fate, of humanity, of spirits, of the role and function of astrology in understanding fate etc. You gotta historicize astrology and its concepts to actually try to use them, and it's probably not a good idea to use everything, especially before undertanding their conceptualization.

I don't use Lilly's Lord of Geniture or the arabic Almuten Figuris, so I particularly don't study those in depth. I focus on hellenistic astrology, and for Porphyry, for example, there's a connection between the Master of the Nativity (Oikodespotes) and the native's personal daimon, which is another complicated and divisive concept that's ingrained in Astrology and that you can find clarifications about in Dorian Greenbaum's book "The Daimon in Hellenistic Astrology: Origins and Influence". If you're going to read one thing about this topic in the hellenistic perspective it has to be that book. There you will also find explanations of the ideas and methods of the different hellenistic authors for these "lords" and "masters", about what they are and what they do. There's also Demetra George's book "Astrology in Theory and Practice: A Manual of Traditional Techniques, Volume II: Delineating Planetary Meaning”, part nine, where she teaches the different methods and help you understand the very interesting "Nautical Metaphor". If you have difficulty finding these books, you can talk to me through chat.

#hellenistic astrology#traditional astrology#almuten#lord of geniture#nautical metaphor#william lilly#arabic astrology#book recommendations#daimon#lord of the nativity#master of the nativity#demetra george#dorian greenbaum#answered

0 notes

Text

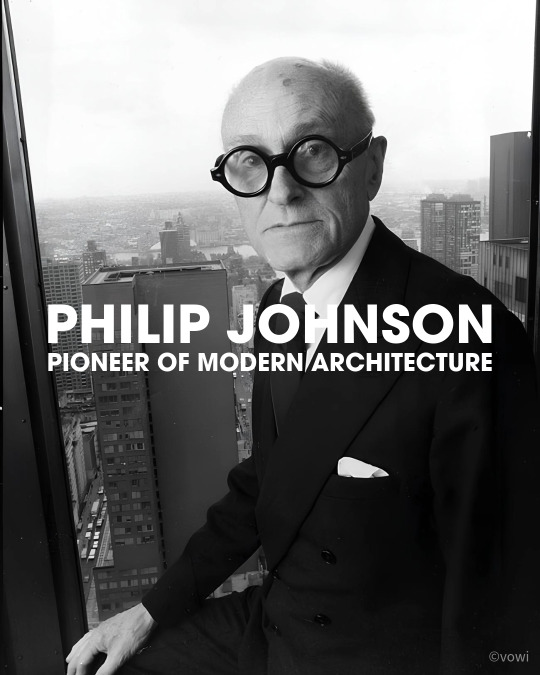

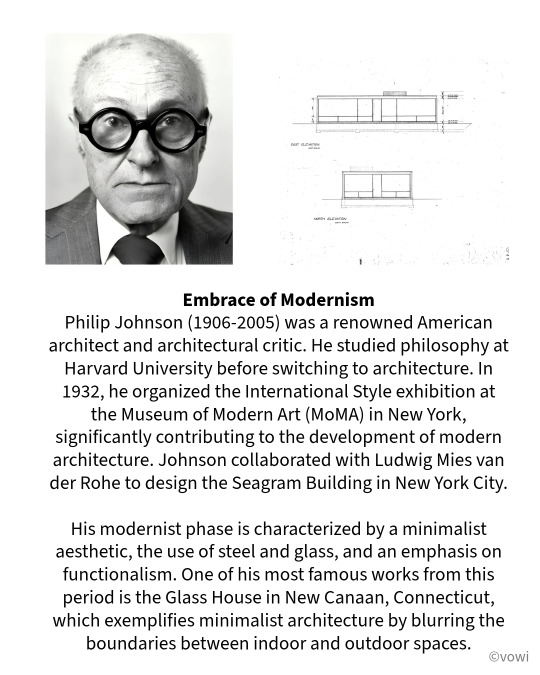

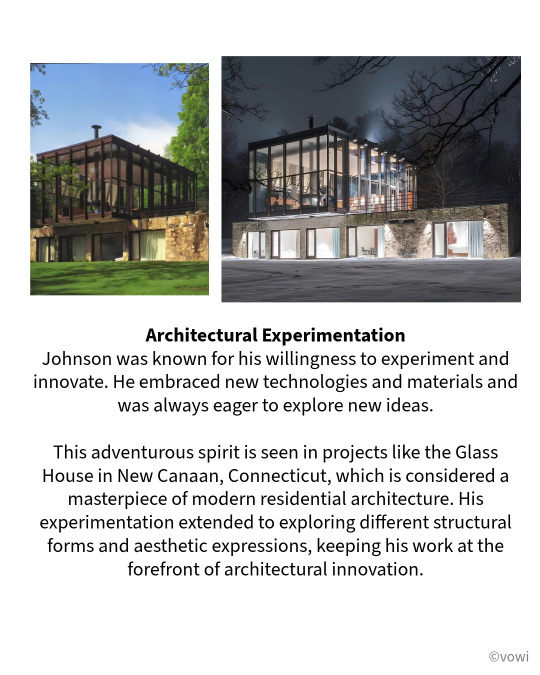

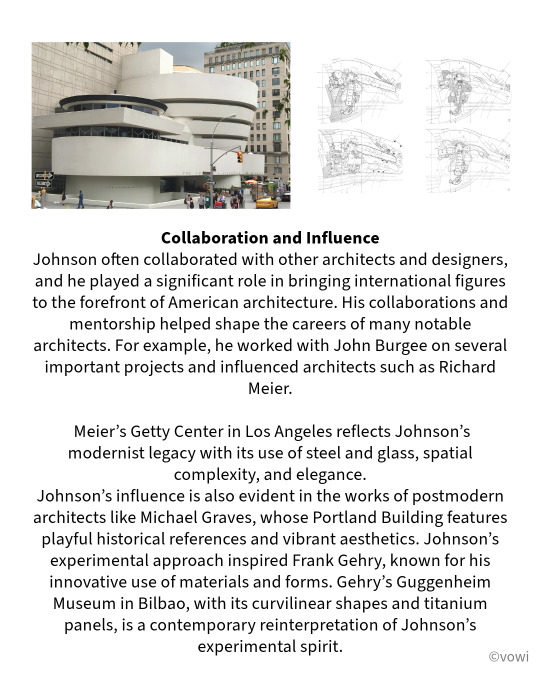

Philip Johnson (1906-2005) was a seminal figure in American architecture whose philosophy evolved significantly over his long career, reflecting his engagement with both Modernism and Postmodernism. Initially, Johnson was a staunch advocate for Modernism and played a crucial role in promoting the International Style in architecture. He co-authored “The International Style: Architecture Since 1922” with Henry-Russell Hitchcock, a book that was instrumental in defining and promoting this style. The International Style emphasized functionalism, simplicity, and the use of new materials such as glass, steel, and concrete. Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, is a quintessential example of this period, characterized by its transparent walls and minimalist design, reflecting the principles of openness and clarity.

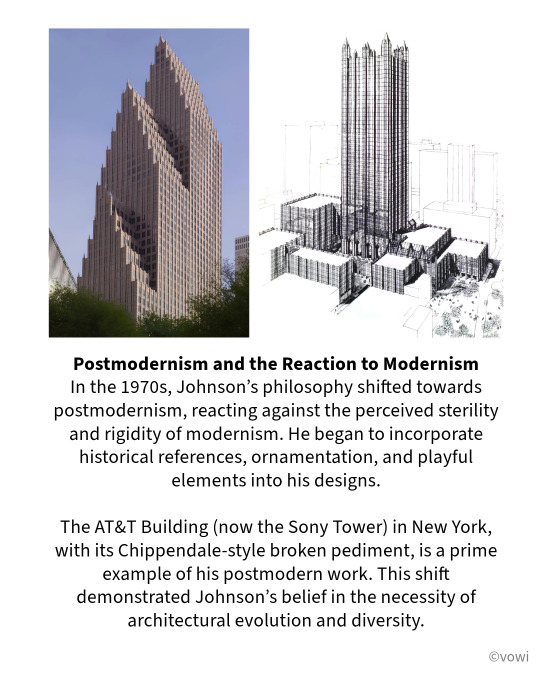

In the 1970s and 1980s, Johnson’s architectural philosophy shifted towards Postmodernism, reflecting a broader trend in architecture that sought to move away from the perceived rigidity and lack of ornamentation in Modernism. Postmodernism in Johnson’s work often involved eclecticism, historical references, and a reintroduction of ornamentation. He believed that architecture should not only be functional but also evoke historical and cultural contexts, often incorporating classical elements in a playful and ironic manner. One of his most famous Postmodern works, the AT&T Building (now the Sony Building) in New York, features a Chippendale-style broken pediment at the top, symbolizing this return to historicism and decorative architecture.

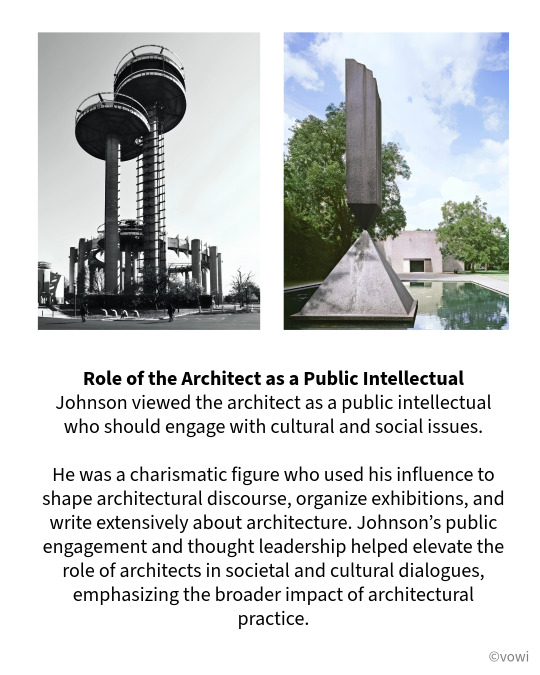

Johnson’s architectural journey reflects his belief in the constant evolution of design and the importance of context in architecture. He was known for his ability to adapt and reinvent his style according to contemporary trends while maintaining a critical dialogue with architectural history. His work and writings underscore the idea that architecture should respond to its time and place, balancing innovation with tradition. This adaptability and openness to change made Johnson a pivotal figure in 20th-century architecture, influencing both the Modernist and Postmodernist movements significantly.

Throughout his career, Johnson collaborated with other notable architects and designers, which enriched his architectural practice. His partnership with Mies van der Rohe on the Seagram Building in New York is a notable example of his Modernist phase, demonstrating the sleek, functional aesthetics of the International Style. Conversely, his later works, such as the PPG Place in Pittsburgh, showcased his Postmodernist sensibilities with its neo-Gothic details and glass facade. Johnson’s ability to oscillate between and blend different architectural philosophies speaks to his enduring legacy as a versatile and forward-thinking architect who continuously pushed the boundaries of design.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Fady] Joudah’s startling and philosophical new book, [...], comes out this March. The title, as Joudah explained to me, functions as a pictogram: a pictorial symbol that transports meaning by representing a physical object. It also evokes silence and erasure—I see an enclosed space, a ruined building with people inside, or even a book. Within its pages, the poet’s voice travels across centuries and continents, historicizing the fate of the Palestinian people while illuminating the bewilderment, eros, and spirituality of everyday life. Joudah’s integrity and craftsmanship elasticize the boundaries of the lyric and embrace a reckoning with colonial violence. But these glimmering, layered poems defy easy categorization, even as they brim with the wisdom we inherit from the dead: “From time to time, language dies. / It is dying now. / Who is alive to speak it?”

Aria Aber, from her introduction to her interview with Fady Joudah: "Fady Joudah | The poet on how the war in Gaza changed his work", published in The Yale Review, February 28, 2024

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Alfred Brown, from Stocking’s Functionalism Historicized.

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown is the only anthropologist I know of who had a signature cocktail. He called it the ‘Claire de Lune’: one one-third gin, one-third kirsch, one sixth lemon juice and one sixth orgeat. (Stocking, “Radcliffe-Brown’s receipts: the nomothetic of everyday life, p. 10 in HAN 5(1) 1978.) Radcliffe-Brown’s eccentricity did not stop there. He spent his entire life cultivating the air of the sophisticated bohemian, affecting “a cloak and opera-hat on inappropriate occasions” (Kuper Anthro and Anthros 1st ed. 41). He “had even thought out the best position in which to sleep,” recounted one admirer, “Not on the back, not whole on the side, and not like a foetus.” (Watson, But to what purpose, p. 63).

'Cultivated’ is the right word for it. He was born Alfred Brown, ‘A.R. Radcliffe-Brown’ being the hyphenated personality he concocted over the course of his life. There were “so many other Browns in the world” (Stocking After Tylor, 304) he remarked, that it seemed only fair to change his name. Most people called him R-B, while his friends called him ‘Rex’. The larger than life mystique he developed for himself was half English aristocrat and half Paris savant and definitely a conscious project of self-creation.

In fact, Alfred Brown was born in 1881 “of undistinguished Warwickshire stock” (Stocking, After Tylor 304). His father died when he was five, leaving his family penniless. R-B lived with his grandparents and soon found success through study, earning a scholarship to Cambridge in 1901, where he was first exposed to anthropology. In 1898 the university had sent a large, interdisciplinary team of researchers to the Torres Straits, the narrow body of water separating Australia and New Guinea. Very little was known of the area at the time, and Torres Straits expedition, as it was known, investigated both sides of the straits, using what were then the latest techniques in the new fields of anthropology, psychology, and linguistics. The main members of the team for our purposes here were W.H.R. Rivers, A.C. Haddon, and C.G. Seligman. Seligman would move on to the LSE and be a teacher of Malinowski, but the others continued their association with Cambridge, forming a ‘Cambridge School’ of anthropology. This was the version of the discipline that Radcliffe-Brown would encounter in his student days.

Brown earned his degree at Cambridge in 1904 and obtained another Cambridge-sponsored grant to conduct research in the Andamans, an isolated chain of islands between what is now Myanmar and India. The islands were seen by the British as one of the many last bastions of unexplored primitivity they could explore, featuring in the popular 1890 Sherlock Holmes story The Sign of the Four. For most of the 19th century the British used it as a harbor for ships moving between India and Burma (then both under British control) and as a prison. When Radcliffe-Brown visited the island its “negrito” were seen as the lowest form of life in Asia, perhaps possibly related to African pygmys. Today, the evidence suggests they are genetically related to Malaysian people and strongly resisted British forces, who ‘pacified’ the region violently and used its prison to isolate and incarcerate Indian activists striving for independence.

It turns out Radcliffe-Brown was not much of a fieldworker. Although he describes himself as having spent the years 1906 to 1908 in the Andamans, most of his actual fieldwork involved ten months of research at Fort Blair, the British military outpost, where he interviewed nearby Andamanese in an attempt to reconstruct their ‘primitive’ social organization as it existed before the arrival of the British. He gave up working in the other, less colonized islands because it would have involved spending years learning the language. “I ask for the word ‘arm’ and get the Önge for ‘you are pinching me’,” he wrote. [this from Stocking, After Tylor 306-307].

In 1908 he returned to Cambridge. His fieldwork was only a partial success, but he had done it, and he won a fellowship at Trinity. He spent the next several years lecturing in England at the LSE, Birmingham, Cambridge, and other places. It was during this period that Radcliffe-Brown undertook another bout of research between 1908 and 1910, this time in Australia. Australia was seen as a particularly good place to do research because Aboriginal people were viewed as especially primitive remainders of human nature in the raw. Radcliffe-Brown’s expedition again got mixed results. He was paired with Daisy Bates, a now-famous female explorer, but they quarreled. Radcliffe-Brown got a sense of Australian colonialism when a ceremony was broken up by white settlers seeking to arrest Aboriginal people. Radcliffe-Brown ended up hiding them in his tent.

During his lectureships in England from the period of 1910 to 1914 Radcliffe-Brown continued to shape his own views. His Francophilia grew, as he discovered the work of Emile Durkheim and, especially, Marcel Mauss. Mauss corresponded with Radcliffe-Brown and Radcliffe-Brown began to see Durkheimian sociology as a novel and powerful theoretical form that could be applied to the nascent theories of ‘primitive’ social organization developed by Rivers. In 1914 he hyphenated his named, becoming finally A.R. Radcliffe-Brown.

R-B in Australia in 1928

In 1914 he attended the same conference in Australia as Malinowski, and like Malinowski he found himself stranded without funds when World War I broke out. Too old to enroll in the war (he was in his early thirties when it began) or get back home, and out of money, he took up a job at a grammar school in Sydney and eventually got a position as Director of Education for Tonga [After Tylor 324]. He tried mixing in a bit of fieldwork but was again frustrated by the need to learn a local language and spend a significant amount of time in the field. After the war, in 1919, he contracted tuberculosis and went to go live with his brother in South Africa.

In 1921(?) Radcliffe-Brown was appointed to the inaugural chair in anthropology at the University of Cape Town. He was not an active fieldworker in Africa, but used teaching as an opportunity to develop his own theories of social organization. These were most clearly on display in his 1922 book Andaman Islanders, in which he took ethnography from his earlier fieldwork and analyzed it using the framework he had learned from Mauss and Durkheim. But R-B became best known not for his book but for his essays, written versions of his lectures in which he expounded his systems of thought with great clarity. He used these essays to break with historicism, which he associated not with a scrupulous Boas particularism, but with a conjectural history which explained ‘primitive’ societies in terms of survivals.

How did Radcliffe-Brown envision the relationship between politics and the academy while in South Africa? Importantly, he looked at South Africa in a politically progressive way as a single society composed of different groups, rather than two different ���cultures’ or ‘races’ meeting. This latter position was politically conservative in the South African context and played into apartheid discourses of the necessity of separate spheres for black and white, and ‘preserving’ African culture by denying Africans western education and restricting them to ‘tribal’ territories. That said, Radcliffe-Brown was hardly an activist. He believed in pursuing anthropology as a pure science - what we might call today ‘basic research’ — and did not believe it should be sullied with applied work, despite the fact that it offered, he claimed, objective truths about the social situation which administrators and politicians did not have access to. Rather, he used anthropology’s Pure Scientific Knowledge to criticize government policy which was uninformed by his insights. This stance was offered both relevance but also distance, and is a position which many anthropologists have taken from the safety of their ivory towers.

After five years at Cape Town, Radcliffe-Brown took up another inaugural chair in anthropology (support for which came from Orme Masson, an influential Australian professor and also Malinowski’s father-in-law), this one at the University of Sydney. Being at Sydney gave Radcliffe-Brown the ability to influence who was doing fieldwork not only in Australia, but in much of the southwest Pacific, including New Guinea. The position was supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, whose sought to provide training in anthropology to colonial officers serving in New Guinea and elsewhere in the Pacific. The results were mixed. Radcliffe-Brown’s structure functionalism was inherently conservative: since every institution in a society had a function, any change to the structure would be pathological. This was not the news that colonial authorities wanted to hear, since their goal was to change the societies they encountered, both for humanitarian reasons and for profit.

R-B around 1930, via an earlier tumblr post.

In 1931 Radcliffe-Brown moved again — this time to the University of Chicago. Chicago was the first place where he had taught in which he was not creating an anthropology program from scratch. Indeed, it was the first country in which there was already a well-developed and active program of anthropological research. As we have seen, in the pre-professonial days, anthropology was dominated by east coast departments such as Harvard, Yale, Penn, and Columbia, each of which were centers of intellectual life for each state they were in, and attached to a museum. Chicago was an upstart, the major academic power in the American midwest, and richly funded by Rockefeller money when it opened in 1890. The older, east coast departments emerged out of an English tradition derived ultimately from Oxbridge. Chicago was designed as a pure research university in the German tradition — ‘the college’, as it was called, was tacked on to the ‘university’ which granted higher degrees. Anthropology’s foothold at Chicago was established by Frederick Starr, one of the most ultra-creepy and deeply racist anthropologists I’ve run across. He was replaced in 1924 by Faye Cooper Cole, a Boasian who was an able administrator whose goal was to build up the department by importing talent. He first hired Edward Sapir, the best Boasian available given that Kroeber was at Berkeley. In 1929 anthropology became a separate department from sociology. In 1931,When Sapir left, Cole looked for his next star and found Radcliffe-Brown.

Radcliffe-Brown helped put his unique spin on Chicago, a place which in its midwest isolation was already developing its own unique style. Radcliffe-Brown’s ahistorical ‘functionalism’ was different, he claimed, than the ‘historical’ school of the Boasians. He developed the study of North American kinship systems — which ended up being far more complicated than he had thought — and produced a generation of students who, along with Sapir-trained Robert Redfield and R-B’s old friend and student W. Lloyd Warner, would shape the department in the future.

Perhaps this is a good place to mention Radcliffe-Brown as a mentor. His global peregrinations prevented him from creating a circle of dedicated students the way Mauss, Boas, and Malinowski did. This lack of a Radcliffe-Brown ‘school’ was not just the result of his travels, but also seemed deeply ties to his character. By his time in Chicago in the 1930s, Alfred Brown had transformed himself into A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, a glittering Svengali of anthropology. He appears not to have had much of a private life, and was married and divorced early in his life. He did not have messy love-hate relationships full of intense and ambivalent relationships with his students as Malinowski did, nor was he a family man the way Boas was. He cultivated awed disciplines who adhered unquestioningly to his beautiful theories. Most of his career focused on teaching undergraduates, and his speciality was the lecture. As someone once remarked (Gluckman iirc), he has trouble teaching graduate students because he had already taught them his entire system at the lecture. At Chicago he had students he worked closely with, such as Fred Eggan, but he did not found a school. Rather, he was one more influence in a rich mix of intellectual currents. [drawing on Stocking’s chapters in After Tylor]

An elderly R-B, probably from his Oxford days, via the Pitt-Rivers.

Radcliffe-Brown’s day finally arrived in 1936. R.R. Marett, the reader of anthropology at Oxford, was going to retire, so All Souls (a wealthy college) agreed to food the bill for a professorship in anthropology, mostly, apparently, to avoid being taxed by the university during the depression, when wealthy and ancient colleges like All Souls maintained embarrassingly plush balance sheets. at a time when others struggled. Malinowski was first offered the position, but was happy in London, and Radcliffe-Brown was selected to fill the position [drawn from ch. 3 and 4 of Riveiere’s Oxford Anthropology]. This was an important turning point for anthropology in the UK — for the first time, the ‘functional revolution’ had a firm hold at Oxbridge.

Malinowski was Radcliffe-Brown’s frenemy, united with him against the older anthropology but sparring for funds to create the new anthropology. In the 1930s they had jousted for control of Rockefeller money, and students moved in and out of their orbits. Malinowski’s massive two volume 1934 ethnography Coral Gardens and Their Magic set new records for empirical detail but seemed to offer little in terms of the new objective Science of Man that Malinowski promised his funders (“I know a lot about yam growing after reading it, I can tell you,” Quipped Godfrey Wilson [Fires Beneath loc 2093]. Radcliffe-Brown, on the other hand, had a genuine theoretical system. For the more discerning English anthropologists, such as E.E. Evans-Pritchard, he offered a much more British and drama-free environment than Malinowski. Friday pub nights with Max Gluckman, Evans-Pritchard, and Meyer Fortes helped endear Radcliffe-Brown and his social systems to some of the most up and coming anthropologists of the next generation [Riviere, Oxford Anthropology, p. 90]. In an unusual twist of fate Malinowski left for America on a speaking tour in 1938, only to be stranded there by the outbreak of World War II. He would never return. Oxford was now the center for the new anthropology.

R-B did not impress Oxford as he had Capetown and Sydney. His larger-than-life bohemian personality seemed pushy and arriviste in an institution which had valued conformity and tradition for literally a thousand years. Marett had advocated for what we might call a “four-field” approach in anthropology, including physical anthropology and archaeology, with a focus on museum collections (in this case, the Pitt-Rivers museum). Oxford, like Cambridge, was still focused on undergraduate teaching. Radcliffe-Brown, drawing on Malinowski’s success at the LSE, tried to transform Oxford into a center for graduate education. But the LSE was a new institution, with strong top-down leadership (whose ear Malinowski had) and a willingness to innovate. Radcliffe-Brown was unable to move conservative Oxford, and his innovations were seen by the existing community of anthropologists as a threat, ‘disaster’ as Beatrice Blackwood called it. His various attempts to get external funding, or move internal college and university funding were also unsuccessful. He requested that the anthropology department be turned into an ‘institute’, a request which the university did not approve. He simply changed the name on the door and printed new business cards! Eventually, the change was accepted. The depression no doubt didn’t help but neither, likely, did his personality — he lacked the tact and charm of Firth and Malinowski. [Mills in History of Oxford Anthropology].

The elderliest R-B, from his Oceania obituary.

Worse, World War II altered British national priorities in important and unforeseen ways. Radcliffe-Brown was 55 when he was hired at Oxford — just in time to watch students empty out of the university and into the military. He eventually left as well, spending the second half of the war in Brazil, trying to start an anthropology program in Sao Paolo. When the war was over so was his career: He retired in 1946 at the age of 65 (the standard year of retirement). During the war he had dreamed of returning to the United States, but bounced around in Egypt and South Africa (partially seeking drier warmer climates since, as he told Warner, he could not live in Britain in the winter any more) before settling in London. He died in 1955.

#Oceania (journal)#Functionalism Historicized (book)#A.R. Radcliffe-Brown#anthropology#portrait#pitt-rivers museum#W Lloyd Warner (book)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Analysis Part 1 - Hermeneutics and Configurative reading (the “what” part)

“Without turning, the pharmacist answered that he liked books like The Metamorphosis, Bartleby, A Simple Heart, A Christmas Carol. And then he said that he was reading Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's. Leaving aside the fact that A Simple Heart and A Christmas Carol were stories, not books, there was something revelatory about the taste of this bookish young pharmacist, who ... clearly and inarguably preferred minor works to major ones. He chose The Metamorphosis over The Trial, he chose Bartleby over Moby Dick, he chose A Simple Heart over Bouvard and Pecouchet, and A Christmas Carol over A Tale of Two Cities or The Pickwick Papers. What a sad paradox, thought Amalfitano. Now even bookish pharmacists are afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze a path into the unknown. They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters. Or what amounts to the same thing: they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.” ― Roberto Bolano, 2666

Much of the background for this post in particular comes from Paul Fry’s Yale lecture course about the theory of literature. This is a great starting course for interpretation and textual analysis and, yes, film and TV shows are text.

In futzing around with this stuff, what am I doing? Less charitably, what do I think I’m even trying to do, here? Many feel that applying theory to art and entertainment is as pretentious as the kind of art or entertainment that encourages it. It’s understandable. Many examples of analysis are garbage and even people capable of good work get going in the wrong direction due to fixations or prejudices they aren’t even aware of and get swept away by the mudslide of enthusiasm into the pit of overreach. That’s part of the process. But this stuff has an actual philosophical grounding, so let’s start by looking at the stories history of trying to figure out “texts.”

Ideas about the purpose of art, what it means to be an author, and how it is best to create go back to the beginning of philosophy but (outside of some notable examples) there is precious little consideration of the reception of art and certainly not a feeling that it was a legitimate field of study until more recently. The Greeks figured the mind would just know how to grok it because what it was getting at was automatically universal and understanding was effortless to the tune mind. But the idea that textual analysis should be taken seriously began with the literal texts of the Torah (Rabbinical scholarship) and then the Bible, but mostly in closed circles.

Hermeneutics as we know it began as a discipline with the Protestant Reformation since the Bible was now available to be read. Sooooo, have you read it? It’s not the most obvious or coherent text. Reading it makes several things clear about it: 1. It is messy and self contradictory; 2. A literal reading is not possible for an honest mind and isn’t advisable in any event; 3. It is extremely powerful and mysterious in a way that makes you want to understand, your reach exceeding your grasp. This is like what I wrote about Inland Empire - it captures something in a messy, unresolvable package that probably can’t be contained in something clear and smooth. This interpretive science spread to law and philosophy for reasons similar to it’s roots in text based religion - there was an imperative to understand what was meant by words.

Hans-Georg Gadamer is the first to explicitly bring to bear a theory of how we approach works. He was a student of Martin Heidegger, who saw the engagement with “the thing itself” as a cyclic process that was constructive of meaning, where we strive to learn from encounters and use that to inform our next encounter. Gadamer applied this specifically to how we read a text (for him, this means philosophical text) and process it. Specifically he strove to, by virtue of repeated reading and rumination which is informed by prior readings (on large and small scales, even going back and forth in a sentence), “align the horizons” of the author and the reader. The goal of this process is to arrive at (external to the text) truth, which was for him the goal of the enterprise of writing and reading to begin with. This is necessary because the author and reader both carry different preconceptions to the enterprise (really all material and cultural influences on thinking) that must be resolved.

ED Hirsch had a lifelong feud with Gadamer over this, whipping out Emanuel Kant to deny that his method was ethically sound. He believed that to engage in this activity otherizes and instrumentalizes the author and robs them of them being a person saying something that has their meaning, whether it is true or false. We need to get what they are laying down so we can judge the ideas as to whether they are correct or not. It may be this is because he wasn’t that sympathetic a reader - he’s kind of a piece of work - and maybe his thheory was an excuse to act like John McLaughlin. He goes on to have a hell of a career fucking up the US school system

But it’s Wolfgang Iser that comes in with the one neat trick which removes (or at least makes irrelevant) the knowability problem, circumvents the otherizing problem, and makes everything applicable to any text (e.g. art, literature) by bringing in phenomenology, specifically Edmund Husserl’s “constitution” of the world by consciousness. It makes perfect sense to bring phenomenology into interpretive theory as phenomenology had a head start as a field and is concerned with something homologous - we only have access to our experience of <the world/the text> and need to grapple with how we derive <reality/meaning> from it. Husserl said we constitute reality from the world using our sensory/cognitive apparatus, influenced by many contingencies (experiential, cultural, sensorial, etc) but that’s what reality is and It doesn’t exist to us unbracketed. Iser said we configure meaning from the text using our sensory/cognitive apparatus, influenced by many contingencies (experiential, cultural, sensorial, etc) but that’s what meaning is and It doesn’t exist to us unbracketed. Reality and meaning are constructed on these contingencies, and intersubjective agreement is not assured.

To Iser, we create a virtual space (his phrase) where we operate processes on the text to generate a model what the text is saying, and this process has many inputs based on our dataset external to the text (not all of which is good data) as well as built in filters and mapping legends based on our deeper preconceptions (which may be misconceptions or “good enough” approximations). Most if this goes on without any effort whatsoever, like the identification of a dog on the street. But some of it is a learned process - watch an adult who has never read comics try to read one. These inputs, filters, and routers can animate an idea of the author in the construct, informing our understanding based on all sorts of data we happen to know and assumptions about how certain things work.

This is reader response theory, that meaning is generated in the mind by interaction with the text and not by the text, though Stanley Fish didn’t accent the “in the mind part” and name the phenomenon until years later. Note that Gadamer is largely prescriptive and Hirsch is entirely prescriptive while Iser is predominantly descriptive. He’s saying “this is how you were doing it all along,” but by being aware of the process, we can gain function.

For those keeping score: 1. Gadamer, after Heidegger’s cyclic process at constructing an understanding of the thing itself, centers on a point between the author and reader and prioritizes universal truth. 2. Hirsch, after Kant’s ethical stand on non instrumentalization, centers on hearing what the author is saying and prioritizes the judging the ideas. 3. Iser, after Husserl’s constituted reality, centers on configuring a multi-input sense of the text within a virtual (mental) space and prioritizes meaning.

Everything after basically comes out of Iser and is mostly restatement with focusing/excluding of elements. The 20th century mindset, from the logical positivists to Bohr’s view that looking for reality underlying the wave form was pointless, had a serious case of God (real meaning, ground reality) is dead. W.K. Wimsatt and M. C. Beardsley’s intentional fallacy, an attempt to caution interpreters to steer clear of considering what the god-author meant, begat death of the author which attempted to take the author entirely out of the equation - it was less likely you’d ever understand the if you focused on that! To me, this is corrective to trends at the time and not good praxis - it excludes natural patterns of reading in which the author is configured, rejects potentially pertinent data, and limits some things one can get out of the text.

Meanwhile formalism/new criticism (these will be discussed later in a how section) focused on just what was going on in the text with as few inputs as possible, psychoanalytics and historicism looked to interrogate the inputs/filters to the sense making process, postmodernism/deconstruction attacked those inputs/filters making process questioning whether meaning was not just contingent but a complete illusion, and critical studies became obsessed with specific strands of oppression and hegemony as foundational filters that screw up the inputs. But the general Iser model seems to be the grandfather of everything after.

Reader intersubjectivity is an area of concern. In the best world, the creation of art is in part an attempt to find the universal within the specific, something that resonates and speaks to people. A very formative series of David Milch lectures (to me at least) proffer that if you find a scene, idea, whatever, that is very compelling to you, your job is to figure out what in it is “fanciful” (an association specific to you) and how to find and bring out the universal elements. But people’s experiences are different and there be many ideas of what a piece of art means without there being a dominant one. So the building of models within each mind leaves a lot to consider as the final filtered input is never quite the same. There is a lot of hair on this dog (genres engender text expectations that an author can subvert by confusing the filter, conflicting input can serve a purpose, the form of a guided experience can be a kind of meaning, on and on ad nauseum)

The ultimate question, you might ask, is why we need to do this at all. I mean, I understood Snow White perfectly fine as a kid. There’s no “gap” that needs to be leaped. The meaning of the movie is evident enough on some level without vivisecting it. The Long answer to what we gain from looking under Snow’s skirt is the next episode. The short is: 1. You are doing it anyway. That Snow White thing, you were doing thhat to Snow White you just weren’t conscious of the process.

2. It’s fun. The process only puts a tool of enjoyment in your arsenal. You don’t have to use it all the time.

3. You’ll see stuff you like in new ways. The way Star Wars works is really interesting!

4. It may give dimensions to movies that are flawed or bad, and you might wind up liking them. Again, more to love.

5. It is sometimes necessary to get to a full (or any) appreciation of some complicated works as the most frustrating and resistant stuff to engage with is sometimes the most incredible.

6. It reinforces your involvement in something you like. It makes you more connected and more hungry, like any good exercise.

7. You can become more aware of what those preconceptions and biases are, which might give you insights in other areas of your life.

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The tension between the sheer interest of difference and the representative function exposes what is most problematic in Buurma and Heffernan’s history of the discipline, a surprising reduction of this history to one of sameness and indifference, a history without history. In The Teaching Archive’s history of literary study, trends, movements, schools, and revolutions are, in the end, illusions. Some differences disappear altogether, as with the political differences between [TS] Eliot and [IA] Richards, or [Cleanth] Brooks and [Edmund] Wilson. The discipline was always much as it is today. The spectacular revisionism of this history will no doubt captivate readers who are weary of conflict, because it is difference that gives rise to conflict. But I don’t believe that the remedy for this weariness is to make the discipline’s history of conflict disappear. It may be true that on the ground of teaching, in the classroom, where the perspective is here and now, where the horizon is tomorrow’s class, the longer history of methodological conflict is not so urgent a concern. But this history is not an illusion. In Buurma and Heffernan’s account of the discipline, the division between critic and scholar, between teaching and scholarship, between formalism and historicism — and all other possible antagonisms — cease to animate conflict: This book rejects the idea that our discipline has been pulled in two directions, that its core has been formed by controversy over method or that its goals of producing knowledge about literature and appreciating literature have been mutually exclusive. Formalism and historicism, we argue, are convenient abstractions from a world of practice in which those methods rarely oppose one another. I would agree that this statement is true in the classroom, that good teaching is not just partisan polemic. But I would also say that a conflict such as that between formalism and historicism is not just a matter of abstraction, that something needs to be argued here in theory, and that there are stakes in the weighting of these scales. A similar reservation applies to Buurma and Heffernan’s repudiation of the received history of the discipline. In that history, there are two major moments of crisis, with subsequent periods of resolution and unwinding: the first saw the emergence of the discipline proper, with Practical Criticism and New Criticism. The second saw the unwinding of that disciplinary formation with the assimilation of Continental theory and the impact of the New Social Movements on literary study. Here again, Buurma and Heffernan want to argue that there is nothing but the illusion of change: “‘[I]dentity politics’ has flourished in all eras.” And: “Far from being a post-’68 phenomenon, ideology critique — Marxist and otherwise — threads through literature classrooms across the entire twentieth century.” It is true that the work of J. Saunders Redding precedes the African American studies programs of the post-’60s; and it is true that there were Marxists like Edmund Wilson before Fredric Jameson. But something did happen in the ’60s that transformed the discipline of literary study, along with the university and the nation. Buurma and Heffernan don’t deny this, but want to direct our attention elsewhere: “[A] disciplinary historical focus on practice rather than theory reveals interconnections rather than oppositions and continuities rather than ruptures.” At this fork in the road, I worry that Buurma and Heffernan are giving us a choice that we don’t need to make, and which they don’t need to make. This is the choice between conflict and collaboration. We need both in order to account for the history of the discipline, a conclusion that I draw with the help of The Teaching Archive itself, its vivid portraits of teacher-scholars, both their differences and what they have in common. If the literary professoriate has sometimes forgotten what happens in the classroom, it is the great contribution of this book to remind us that without collaboration, there is no teaching, and that without teaching, the discipline has no history.

John Guillory, “‘Flipping’ the History of Literary Studies,” (review of Heffernan and Buurma’s The Teaching Archive) in LARB (x)

#john guillory#rachel sagner buurma#laura heffernan#the teaching archive#book reviews#literary history#literary pedagogy

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some thoughts about Bran Stark

Okay, so--not to butt in and trample around, as someone who never read the books and stopped watching the show sometime around season 3--but the thing is, I feel like the ending has finally allowed me to understand exactly what it was that turned me off Game of Thrones, which I never quite did put my finger on till now, and I want to at least write it out once. (Ironically, this has made me like the story better, though not its execution.) To attempt a spoiler-free summary: I’m going to be thinking about the thematic structure of the story and why that should make certain things make sense, and how they came to not make sense anyway.

The thing is, thematically and structurally, Bran ending up king makes absolute and perfect sense. It’s just that they didn’t write the story in line with the structure they were given. The problem with the show is--and always has been--that the writers don’t actually understand what “subverting fantasy tropes” means or could look like, and they don’t care about it in any meaningful way. What they care about is doing big, bloodthirsty, quasi-historical fiction with a lot of nudity. (See: the Civil War show they wanted to do.) And Bran’s whole situation only makes sense (or would have made sense, if executed properly) in the context of high fantasy.

Keeping in mind that complicating high fantasy tropes was an important part of what Martin reportedly set out to do, each of the Stark kids (the story’s backbone) had a clear thematic purpose. Each of them a) was a take on a trope, b) had a clear character trajectory that would allow that take on the trope to be developed while functioning as a working character arc, and c) through that trope-inflected arc, could allow the audience a window into specific part of the society (i.e., they supported the worldbuilding), which in turn allowed the further development of these takes on the tropes by giving them specific, appropriate settings and side characters to bounce off of. This is to say that GRRM did a good job setting himself up to do “trope subversion” in a way that would comment on the things he wanted to comment on, function as part of a larger world and story, and help support a plot that would be in harmony with all of the above. This is one very solid approach to character design. To be clear, despite this paragraph being about characters, I’m talking about themes--it has nothing to do with their personalities or whatever. This is about what ideas come together in the concept of each character and therefore how each character’s story develops the ideas.

A good reason to approach character design in this way is if you have set out to subvert, complicate, comment on, or otherwise mess with genre tropes. To do so, the characters have to themselves be tropes, or at least be designed in close relation to tropes, in order to derange them. So like, just to take the simplest two examples:

Robb: The Prince. Firstborn, shining favorite, destined to inherit. Set up (normally) to avenge his father, restore order to his kingdom, and go home. Bungles it entirely by seeking true love; meanwhile, in the course of his story we learn about the regional politics of the North, the politics of alliances by marriage and kinship, etc. Narratively, his failure allows the entire political and military situation to get infinitely more clusterfucked. All of those pieces fit together well thematically.

What is being subverted here is the prince’s marital destiny. We have loads of fairy and fantasy stories about prince and prince-types for whom pursuing true love just happens to be convenient (they can marry whoever they want), or whose pursuits of love are rescued by fate (his true love turns out to be his promised princess all along! She’s secretly a magical being of some sort, and that trumps betrothal agreements! The one he was originally supposed to marry died or decided to marry someone else! etc). This is totally kosher in traditional high fantasy (or in the folklore that the genre draws on) because it’s an expression of the harmony of the story-world; the characters go through their trials and adventures and end with a resolution in the form of marriage that announces that all is as it should be. What it looks like GRRM set out to do is ask what happens when people still follow those rules and the rules aren’t in harmony with the world they live in.

In particular, the entire thing points square at the fact that princes are political animals. It seems to me that Robb’s story was meant to say, well, actually, sometimes people with power just have to marry people they don’t love as a condition of being powerful (which comes up constantly throughout the whole show). After Ned and Catlyn, basically every “true love” couple is dysfunctional, incestuous (Cersei and Jaime, Daenerys and John), and/or gets narratively stomped on, as far as I’m aware. (Did Sam and Gilly make it? If so, I think that’s allowed because they’re commoners.) Ironically, Ned and Catlyn set Robb up to fuck up by modeling one of these convenient political-and-true-love marriages. He thought he was supposed to be allowed to have it all. He was wrong. The end. Next. But the show seemed to expect me to feel that the outcome was unjust and tragique for Their Love, when all that was unjust and tragique about it was that Robb was idiot enough to bring the consequences of his actions on his entire group of followers. That is the point. That his status has to constrain his behavior, and when it doesn’t it has consequences for others. The status itself is what’s being problematized.

Jon: The Secret Heir. Second-oldest, bastard-born, treated with contempt. In relation to the family, literally a supplementary person. Set up (normally) to be rediscovered as the true heir to the throne and end up as king (moving from the margins to the center; getting the acceptance he couldn’t have as a bastard). The twist is the “true” dynasty he represents is composed of inbred lunatics, and his potential access to the throne goes not only via that bloodline but via repeating their tradition of incest. Dovetailing nicely with that, he was set up from the start as less wanting access to the kinship system than wanting to be free of it, so instead of becoming king by virtue of being a Targaryen, he stops the reinstatement of the Targaryen line altogether. Meanwhile, for most of his story, as a “supplementary person” he gives the audience a view into a lot of corners of Westeros that are concerned with what is excluded from Westeros: the Night’s Watch, the Wildlings, and indeed the White Walkers.

Again, all of that lines up together well. It’s part of the larger derailment of the blood-as-destiny notion of a “true” king, heir, ruling dynasty, etc. (I think the main reason GRRM goes so hard on the incest, not to mention having not one but THREE bastard characters, is in service of this; it also means Jon’s character arc of wanting out of the bloodline system fits into the thematic structure. See? Everything ties together neatly.) But I mean. We all know the character was not executed well.

And so on. I could do the same for Sansa and all the rest of them. (Sansa and Arya are probably the two most successful executions of what their character designs set them up to do; it’s not a coincidence those are the characters whose stories people seem to be happiest with.) But the thing is, a lot of these tropes, while certainly common in high fantasy, are also found in lots of other genres. Chosen Ones and Unexpectedly Eligible Chosen Ones and Princesses and Warrior Maidens (whether in literal forms or not) show up all over the place. The fact that these aren’t strictly fantasy archetypes perhaps means they were less prone to being mishandled. Bran, though. Bran belongs firmly and only in high fantasy. He is, literally, supposed to be a magic priest-king. A take on the Fisher King, even (I’ll explain about that later). And his story was weighted toward the end because of what it seems like Martin was trying to do more broadly, meaning it was much more on the showrunners to do it right.

High fantasy is always trying in some way to engage with ~the numinous~, which is to say the sort of never-explainable mystery and magic of the world. Magic in high fantasy is usually closely tied to deep time, the land, nature, or the metaphysical. Ancient beings, lost secrets, nature spirits, hidden realms, that sort of thing. It’s part of the genre’s inheritance from the mythology and folklore it’s all based on, which had a much more enchanted, vitalist view of the world than we generally do now. (In a way, that’s the purpose for high fantasy’s existence as a modern genre--keeping some access to that.) What Martin set the whole story up to do was question the tropes that often go along with the genre by making the setting one in which almost everybody has forgotten about all the magic and mystical knowledge that is in their history. Westeros is an extreme, historicized take on the Shire, basically. (”English pastoralism you say? I’ll see you and raise you the English Civil War” -- George R.R. Martin, presumably.) They have no notion of what’s really out there and what’s really possible in the world, and have quite comfortably isolated themselves in a situation where they need not remember. As a result, the social institutions that were developed long ago in relation to the ancient magics and knowledges become, instead, just social norms that can be manipulated, distorted, and played out in a much more historical-fiction kind of fashion, which gives Martin lots of room to point out that, say, ironclad patriarchal bloodlines cause problems. (That is, if you take away any magical justification, by virtue of connection to the land or the spirit realm or what have you, for the right to rule, then you stop having to have your One True Kings also be good people. It allows him to pull apart the different pieces of that trope and suggest that their being connected in the first place is questionable. Which it is! He’s right and he should say it!)

But the magic has to come back at some point, or else it’s really not high fantasy. And it seems like what he wanted to do was have all these elements from outside Westeros--the White Walkers, that god whose name I’ve forgotten, and Daenerys with her dragons--converge on it such that the characters would have to go back to their deep history and call those things back up in order to deal with the real world they live in (instead of the wealthy political bubble of all the scheming) and thus get to a point where they could actually change their system for the better. You can think of it as a very elaborate deus ex machina in a way, except the deus ex machina isn’t Daenerys showing up with dragons to fight the White Walkers or Arya having trained (again, outside Westeros, for the record) just the right way for killing the Night King. It’s all of these external forces forcing the characters in Westeros to get their fucking shit together. Otherwise there’s really no resolution to the war, in a high fantasy version of the story. It’s just historical fiction with some weird bells and whistles. Without a need to go back and figure out whatever the First Men were up to, there’s no incentive to go back to the numinous. That he intended for sure that some version of a return of the numinous end up being a big part of the climax is reinforced for me by the fact that the Starks--again, the backbone of the whole story--are set up as being unusually in touch with this mystic/magical heritage (the old gods, the crypt, the godswood) and unusually faithful to the traditional ways. They were introduced that way for a reason.

So where does Bran come in. The thing is that Bran is literally named after the mythic founding king of Westeros, Bran the Builder. The other thing is that both of those Brans are clearly named after Bran the Blessed, a literal mythic god-king from Welsh mythology whose name means crow (but who for various reasons also often gets associated with ravens, which in turn are commonly associated with transcendent knowledge, magic, etc; it’s a long story). So you have a younger member of the story’s key Stark family, already closer to the sources of magic and mystery than most. You name him after the founder of Westeros who lived in a time of magic, traffic with other beings, and great building works and other inherited accomplishments for which the associated knowledge has since been lost, etc. You have him gain mystical abilities to transfer his consciousness to other bodies, or through time (absolutely typical Mystic Powers). You have him even take on a special priestly status passed down from the era of magic by leaving Westeros to hang out with other kinds of magical beings, which means he is now explicitly named both Bran and Raven.

OBVIOUSLY this kid is supposed to be king. He’s going to restore the realm to a situation in which the ruler, the realm, its various life forces and nature spirits, and the metaphysical are all connected to one another and, in a sense, present in the same body (which is the kind of genuine mythological shit high fantasy is always drawing on). But the writers then just sat around and did nothing with him for years on end until whoops hey he’s king now. Of course no one thinks it makes any sense!! It’s fucking malpractice!!!!

If you go to the GOT Wiki and just read Bran’s page, everything makes sense and lines up well in terms of a list of events. (Although it’s really notable how short the entry from s8 is, and how everything it lists is things that happen to Bran, pretty much.) There is a progression that makes sense. But from what I understand--this was certainly the situation when I stopped watching--nothing was ever done to suggest that any of this mattered. The Three-Eyed Raven, the forest spirits, the magics and so on--it was treated at most as a backstory machine. It had no connection to or effect on the rest of the story, so far as I can tell. The fact that none of this played into the battle with the White Walkers at all is flatly insane. The thing I most remember people saying about Bran after that episode wasn’t even “Why didn’t he use X or Y that he learned in the forest?” but “Why was he there?” which just goes to show how completely and utterly bungled this entire piece of the narrative was. Like, if your high fantasy story is making its audience ask “Why would the story put the one character with the greatest knowledge of ancient magics and powers at the scene of a battle against an all-but-forgotten ancient threat,” then I’m sorry, it has gone fully off the rails, and not just in its most recent season. That’s not subversion, it’s just fully dropping the ball.

You know what would make sense as a lead-in to Bran becoming king? Oh, his performing some spectacular feat of insight, magic, strategy, or all three at the battle that no one else could have pulled off because no one else had his background or powers. Even after years of screwing this part of the story over, that could at least have bothered to make a case for why any of it mattered to the rest of the story. It would not have been very subversive, but when you’ve fucked up this royally you don’t get to be precious about your radikal innovative approach, Davids. I can’t believe Peter Dinklage had to sit there and make a bullshit speech about storytelling, when a decently-handled story would have made it seem natural and self-evident by then (you can still have surprises along the way!) that Bran should be king.

Anyway, in closing: part of the reason I checked out when I did was that I felt like they weren’t doing the things I thought they should do as the story developed. Genuinely, one key part of that was that they seemed to be doing absolutely nothing with Bran, which was baffling to me because it seemed obvious to me he was set up to be an incredibly important character. At the time, I thought they were going somewhere close to this with Bran but just taking way too long at it for some reason. What’s now clear is that the showrunners didn’t understand what they should have been doing with him. (Everybody who was taken aback by this outcome is not a fool for not seeing this. They were, quite reasonably, following the narrative cues they were given along the way, all of which said “Bran doesn’t matter.” It’s maybe clearer to me because I stopped watching.) And what that now makes clear, in my opinion, is that they never really understood what Martin was trying to do by “subverting fantasy tropes”; that in fact they didn’t really understand the genre, let alone what subverting it entailed. Which is exactly what bothered me about it even years after I stopped watching, but couldn’t put my finger on--until, ironically, they proved me right about Bran.

#game of thrones#bran stark#bran the builder#bran the blessed#i really tried no to write this bc who wants to get into got discourse right now but i couldn't get it off my mind#so here#i had a whole thing about disability and the fisher king but honestly it wasn't necessary#let's just say i think what martin (presumably) had in mind for ''bran the broken'' was something more complex#probably still fucked up! but differently

384 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silvia Federici has pointed out that alongside the rise of “capitalist technological innovation” there has been “the disaccumulation of our precapitalist knowledges and capacities”:

The capacity to read the elements, to discover the medical properties of plants and flowers, to gain sustenance from the earth, to live in woods and forests, to be guided by the stars and winds on the roads and the seas was and remains a source of ‘autonomy’ that had to be destroyed. The development of capitalist industrial technology has been built on that loss and has amplified it. (191)

This disaccumulation has had strong effects in our very relation to what knowledge is. There is no longer a living knowledge, something directly known. “Life” and “knowledge” become opposed elements: knowledge is value-free and objective where life is valuative and subjective. This is not just the inevitable result of further specialization, but is carried to its extreme limits by the disconnection at all times between the creation of our world and the means by which we do so. Knowledge about how to practice things outside of specific rote mechanical skills is a power and “autonomy” not suitable for the typical wage laborer. Because of this, the modern worldview has approached its knowledge in an alienated and fetishizing way. It accords special status to the end-product of the experiment detached from the purposive, creative activity of the experimenter: its theories and formulae are seen as insights into a value-free, objective nature, while experience, lived time, intentionality etc. are seen as illusory. The essential contradiction that reveals the perversity is that this “value-free” knowledge is acquired by valuing the types of life-activity that will produce it. As A.N. Whitehead put it, “Scientists animated by the purpose of proving that they are purposeless constitute an interesting subject for study.” His point here is literally true: the role of knowledge under capitalist conditions is an anthropological subject that will increasingly attract attention, as an example of these capitalist conditions’ depraved effects.

The American pragmatists, alongside Whitehead, argued against this dualism. The experimental method and the science that it produces is continuous with the rest of nature, having evolved out of it: it is an organic, meaningful process. The way the modern scientist learns is the same way that all lifeforms learn. Eduardo Kohn, following C.S. Peirce, proposed that all living things have a “scientific intelligence”, in that they are capable of learning by experience (77). The forest is teeming with this intelligence in its diverse manifestations, organisms interpreting their environment and producing further signs. It’s in signs that we think and gain knowledge, in the uncertain meanings by which we “read the elements”--and this is always done with some purpose: meanings are means to an end, expressions of an intentionality. As Kohn put it, “it is appropriate to consider telos—that future for the sake of which something in the present exists—as a real causal modality wherever there is life” (37). A living thing acts to achieve an aim, and in the course of doing so it not only conceptualizes and valuates its object of desire but interprets its environment, working according to meaning-structures through which it can interact with the potential future: this potential future is, after all, the location for the possible achievement of its desires. Insofar as the meaning-structures work, they reveal some knowledge: in this way all life produces its science.

There’s no nonarbitrary point at which we can claim a stop to the evolutionary continuity of this valuative activity, even if we find grades of complexity and various distinctions in its modes of being. Just as the boundary at which point one organism stops being one species and evolves into another cannot be given a fixed delineation, the point at which “life” itself begins cannot be defined, so that an absolute outside to it is not rationally conceivable. “Telos,” purpose, must be found everywhere. All becoming occurs according to what the interiority of the becoming thing conceptualizes or intends. However, this interiority in its becoming must relate to its given environment, take on material constraints and direct its intentions to what can be achieved in the given world. The material constraints in their determining capacity habituate desires to flow specific ways. Our technology is dependent not on any eternal laws or corresponding brute mechanisms, but on the habits strongly ingrained in the intentionality of various entities: most especially the entities most typically considered lifeless who seem to show a minimum of will-power, interpretation, or novelty. Modern scientific understanding approaches from the outside in its description of these processes and thus misses the fundamental concept of habit, of a general aim socially pursued in desire. As a consequence these notions--intentionality, desire, generality, value etc.--are rediscovered on the purely human level and given misleading form.

The 21st century has already seen a wealth of thinkers criticizing and attempting to move past this human exceptionalism and dualism, as evidenced in the “posthuman” focus of many thinkers in anthropology and related social sciences, from Eduardo Kohn to Bruno Latour and Donna Haraway. As Federici put it, there is “the emergence of another rationality not only opposed to social and economic injustice but reconnecting us with nature and reinventing what it means to be a human being” (196). But this will not just come about through academics creating new terminology and concepts. Rather, like the shift towards modern thought that accompanied capitalism’s onset, it will be happening within and through movements that change our material basis, i.e. the change in property relations and how they define our ability to work with one another and with our environment. That is to say, these philosophical and anthropological concepts concerning the supersedence of dualism, new understandings of subjectivity and meaning, etc. must be approached historically: their existence is not sustained by an individual consciousness interacting with a book but by the functioning of whole societies. Federici points to one important site for the further emergence of new modes of consciousness in “women’s struggles over reproductive work”:

… there is something unique about this work—whether it is subsistence farming, education, or childrearing—that makes it particularly apt to generate more cooperative social relations. Producing human beings or crops for our tables is in fact a qualitatively different experience than producing cars, as it requires a constant interaction with natural process whose modalities and timing we do not control. (195)

The reproductive labor that has been gendered as “women’s work” may indeed reveal a different logic from the typical view of industrial production that sees it as an instance of what Philippe Descola termed the “heroic model of creation”:

The idea of production as the imposition of form upon inert matter is simply an attenuated expression of the schema of action that rests upon two interdependent premises: the preponderance of an individualized intentional agent as the cause of the coming-tobe of beings and things, and the radical difference between the ontological status of the creator and that of whatever he produces. (323)

Under capitalist conditions the value of reproductive labor is often hidden from being socially recognized, isolated into the domestic sphere, while the dominant mode of socially recognizing the value of our activity occurs through wage-labor and commodification, i.e. through the value-form. The shift away from this bifurcating ordering of production could also mark a shift away from our bifurcation of reality into intentional subjects and brute objects--instead rediscovering a thoroughly intersubjective (and, indeed, interobjective) process.

There’s no question that where we are attempting to reinvent such fundamental categories, we are caught up in a metaphysical and speculative pursuit--and thoroughly metaphysical figures like Whitehead and Peirce have gained new life among recent thinkers--but we also shouldn’t take “metaphysical” thinking to mean an airy detachment. Following Whitehead, I see metaphysics and speculative philosophy as an historical endeavour: as he put it, it is like an airplane that must lift off from a specific moment, spend some time in imaginative construction and reconstruction, and touch back down. I would historicize Whitehead’s thought even further; not to fundamentally alter his methodology nor his scheme of thought, but to point to some differences in the location and situation it is in response to. For instance, Whitehead often overemphasizes the responsibility of Aristotelian philosophy and its notion of substance for modern philosophy’s focus on atomized individuals. We may instead see this as not some development occurring just in the world of philosophy, but rather as a reflection in these modern philosophers’ thoughts of the material development of capitalism, its alienation and atomization. Whitehead offered a radical and deep critique of this alienation in its higher-level ideological expressions, and in doing so passed on a crucial tool for our existential understanding, clearing blockages of long-accumulated modes of thought and shifting the momentum in our perspectives away from those reflecting bourgeois categories. But we must also recognize that these errors in thought are part and parcel of a wider social problem that has to be faced in more than reformulating categories, that the direction of our consciousness towards such reformulations find their drive in the wider struggles of our life.

Works cited:

Descola, Philippe. Beyond nature and culture. University of Chicago Press, 2013

Federici, Silvia. Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons. PM Press, 2019.

Kohn, Eduardo. How Forests Think: toward an Anthropology beyond the Human. University of California Press, 2013.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Sleep Divorce

A year or so ago, I began to sleep apart from my wife a few nights a week, particularly when I stayed up later than her. We have three bedrooms and no one else living with us at present, so there's extra rooms.

My wife says she'd rather we slept together, but I think we both sleep better and get more rest this way.

I am accumulating stories about sleep divorce, as a result.

In 'Sleep Divorce' and the Case for Splitting Up at Night, Mallika Rao, looks into ‘the virtues of splitting up for the night’, and cites several authors on the topic, and threads into the piece her breakup that was motivated in part at least by a desire for sleep privacy:

In this frame of mind, I picked up The Bedroom, a fascinating if somewhat abstruse recent book by the historian Michelle Perrot. Translated by Lauren Elkin from French, it uses the titular space as a laboratory for observers to study the breadth of human nature. Perrot examines texts over several centuries to consider children’s nurseries, workers’ quarters, hotel rooms, and other sleeping chambers. (She limits her focus to the Western Hemisphere.) I was drawn to the book thanks to the neat metaphoric heft of the shared bedroom. It seemed to me that breaking down its history might clarify the social norms that dictate unions more generally. If I understood how the marital bedroom became a presumed standard, I might break from a rigid way of seeing things and open my mind to all the transmutations available to a couple in search of the right form for them. In short, I picked up The Bedroom in hopes of restoring my interest in partnership.

What I believe I found instead is an incidental argument in favor of nightly separation. Despite its pointed historicism, the book reads at times as an annotation to certain ongoing and resolutely modern narratives—a companion script to the past decade in lifestyle news and pop culture. Perrot exhorts readers to take seriously the relevance of sleep to biological and emotional functioning; she discusses the need for new structural norms for marriage; and she frames the bedroom as a haven for respite, a construct with special relevance at a time when a phoneless room can feel like a mythical destination.

She goes on to discuss Balzac’s 1929 work The Physiology of Marriage where he ultimately comes down on the side of separate bedrooms:

Separate bedrooms, then? Not feasible for many of us, but perhaps a conceptual northern star for those in search of peace between obligations to the self and obligations to others (and the promise of a possible palliative, at the very least, for my own anxieties). Perrot name-checks intellectuals who thought as much: Centuries apart, Michel de Montaigne and Jean-Paul Sartre preferred to sleep alone—Montaigne while married, and Sartre while in a partnership with Simone de Beauvoir. So, too, did the writer Virginia Woolf, who slept apart from her husband, Leonard. Her lecture titled “A Room of One’s Own” famously gave rise to the notion that solitude is a prerequisite for serious thought. In modern times, the practice of nightly separation allows for better sleep and comfort, Perrot writes, without “indicat[ing] any lack of love.” Centuries before her, Balzac weighed in with more gusto. Couples who veer into different rooms at day’s end “have become either divorced, or have attained to the discovery of happiness,” he wrote. They “either abominate or adore each other.”

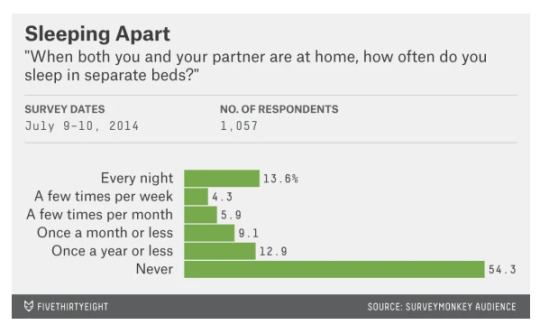

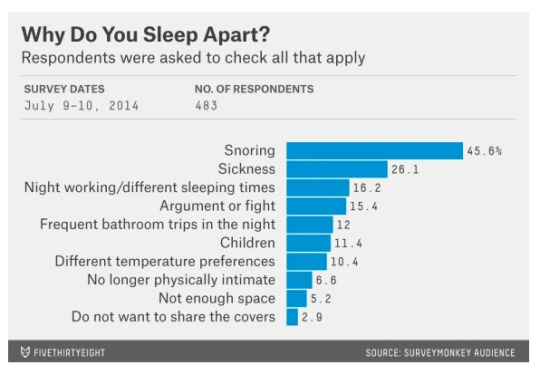

In Dear Mona, How Many Couples Sleep in Separate Beds?, Mona Chalabi of FiveThirtyEight looks into ‘sleep divorce’, statistically.

This seems to omit what I bet is a common case: different sleep ‘weights’ and sleeping times. For example, I go to sleep later and wake up earlier than my wife, and she is a light sleeper. So, if I come to bed at 12am she might wake up and have difficulty going back to sleep, and then she often complain about it the next day. We also fall into the different temperature problem: she likes it cold, with a thick comforter, and I’d rather warmer with just sheet and blanket.

So she is hypothetically unhappy with the sleep divorce, but I am happier by far.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dissertation Prospectus: The Development of South Korean Prisons and Penology, 1945-1961

Dissertation Prospectus

[Please DM for file with full citations]

“The Development of South Korean Prisons and Penology, 1945-1961”

I. Project Overview

Stripped of its legitimating discourses, imprisonment is the simple act of putting human beings into cages. By the mid-twentieth century, the practice of incarceration had spread by means of Western colonial expansion to nearly every area of the globe. Many of the formal vestiges of empire fell away after the second World War, but Western-style incarceration remained a worldwide practice. The project to modernize the Korean prison system continued long after its initial development during the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945). After a chaotic period under the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK; hereafter “MG”) (1945-1948), South Korean penal officials were immediately swept up in bold prison reform efforts. My dissertation research examines the ways South Korean penal reformers imagined the past, present and future of the prison system during Korea’s tumultuous 1950s. I am working to map the cultural, political and economic influences on Korean penology and its discourses in the early Cold War era. The United States government relied on the internal stability of South Korea as an East Asian bulwark against communism, and directly shaped the development of the penal system within the Cold War system. This study has larger implications for the general history of 1950s South Korea, Cold War international relations, and the development of power and social control in the Republic of Korea (ROK) state by historicizing a crucial institution used for state control of the incarcerated and free population alike. This dissertation will argue for rereading the history of the South Korean prison as a crucial site for the production of notions of ROK national identity and citizenship.

The historical timeline of this project extends from Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule and subsequent division by the U.S. and Soviet Union in 1945, through the Korean War (1950-1953) and fall of the Syngman Rhee regime in 1960, and ends with the coup d’etat by General Park Chung Hee in 1961. After the establishment of the Republic of Korea in 1948, penal reformers proclaimed the goal of “democratizing” the prison system under the slogan ‘Democratic Penology’ (minju haenghyŏng). Prior to the Korean War, prisons were underfunded, overcrowded, and used for ostentatious performances of anticommunist conversion. However, by the late 1950s penal officials boasted of the prisons’ humane conditions and state-of-the-art rehabilitative and educational function. Exhibitions displaying prisoners’ paintings, calligraphy, craftworks and writings evidenced their “reformation” for the public. How did the state of prisons change so drastically over a single decade, and how much of these claims is simple propaganda? These purportedly liberal reforms were carried out by the notorious authoritarian regime of South Korea’s first president, Syngman Rhee. Penal practice departed drastically from reformist theory when it came to punishing political opponents of the regime, but the prison system nevertheless did see major changes in the overall treatment of prisoners and training of penal officers. At the same time, this official narrative of reform is conspicuously silent with regard to the state of prisons during the Korean War (1950-1953), a period in which tens of thousands of political prisoners were massacred.