#Friedrich Hollaender

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ich und die Kaiserin (1933), dir. by Friedrich Hollaender

#ich und die kaiserin#Friedrich Hollaender#conrad veidt#paul morgan#hans nowack#and a bit of#heinz rühmann#sci's gifs#the subtitles are a mess#if anyone who knows german could help translate the film better#i would give you my life

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

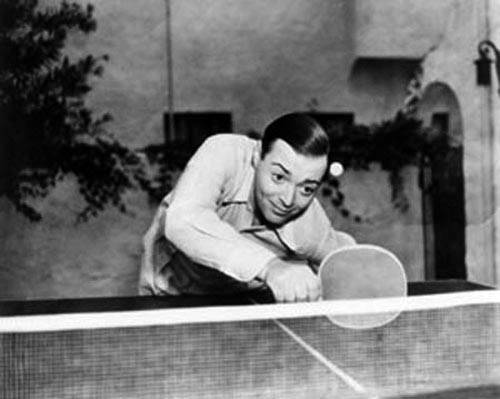

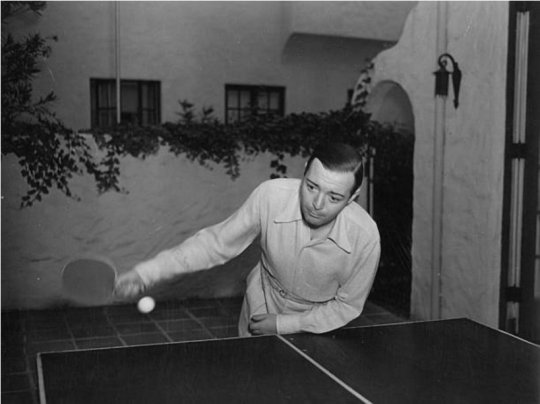

Let's Play Ping Pong With Peter Lorre

Just felt like collecting the Peter Lorre ping-pong pictures in one place. Any others?

The bottom one is Conrad Veidt + Peter Lorre during the simultaneous shooting of the three versions of "F.P.1 antwortet nicht," 1932 (Peter was in the German version, Conrad in the English; Charles Boyer was in the French):

"After dinner, there was only one diversion—Ping-Pong. Much to everyone’s amusement, the six-foot-five Veidt and the five-foot-five Lorre—who tipped the scale at the same undisclosed weight—paired up. 'And these two guys, the one who played ‘Caligari’ and the other one who played the mass murderer in M became a team in Ping-Pong that was unbeatable,' said [screenwriter Walter] Reisch. 'It was not just if we win tonight, it was a matter of life and death to win the tournament. Not for the money, but there was a gala reception afterwards and a medal. And these guys played together like a team, with beautiful timing.'"

And not too much later:

News of Lorre’s arrival in Los Angeles had preceded him by over a month. “In all of the newspapers here, we read of his coming,” Elisabeth Hauptmann wrote Walter Benjamin in Paris. “One has to congratulate the man who engaged the ‘genius actor.’” Hollywood extended a warm welcome to the Lorres. Invitations summoned Peter and Celia to lavish Viennese and Tyrolean dinner parties, where they mixed with old friends such as Fritz Lang, G.W. Pabst, Billy Wilder, and Franz Waxman and met new ones, among them Jean Negulesco, Delmer Daves, Paul Muni, and Olivia de Havilland. The Friedrich Hollaenders also enrolled Lorre—along with Ernst Lubitsch, Conrad Veidt, and Josef von Sternberg—for their Sunday afternoon Ping-Pong tournaments."

All quotes from "The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre" by Stephen D. Youngkin.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Born to Be Bad (Nicholas Ray, 1950)

Cast: Joan Fontaine, Robert Ryan, Zachary Scott, Joan Leslie, Mel Ferrer, Harold Vermilyea, Virginia Farmer. Screenplay: Edith Sommer, Charles Schnee, based on a novel by Anne Parrish. Cinematography: Nicholas Musuraca. Art direction: Albert S. D'Agostino, Jack Okey. Film editing: Frederic Knudtson. Music: Friedrich Hollaender.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“When she plays and sings “Awake in a Dream”, the camera cuts back and forth; Marlene croons and Cooper rolls his eyes and tries to conceal arousal. He blushes in black and white, and his hands are in his pockets for a reason Time magazine then noted was so “sensationally explicit … the Hays organization [was] not sophisticated enough to understand it.”

/ From Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend by Steven Bach, 1992 /

One of the undisputed highlights of Desire (1936) is Marlene Dietrich (clad in exploding black feathers via costumier Travis Banton) throatily serenading a swooning Gary Cooper with “Awake in a Dream”. The song was composed by Dietrich’s frequent and definitive musical collaborator Frederick Hollander (aka Friedrich Hollaender, 1896 – 1976), also responsible for her most-loved signature tunes like “Falling in Love Again”, "Boys in the Back Room," "You've Got That Look,” “I've Been in Love Before”, "Illusions," "Black Market" and “Ruins of Berlin”. Experience it for yourself when the FREE Lobotomy Room cinema club presents Desire at Fontaine’s bar on 15 February! Reserve your seat now by emailing [email protected].

#lobotomy room#marlene dietrich#frederick hollander#awake in a dream#old hollywood#classic hollywood#golden age hollywood#diva#kween#travis banton#gary cooper

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cast: Cary Grant, Ronald Colman, Jean Arthur, Edgar Buchanan, Glenda Farrell, Charles Dingle, Emma Dunn, Rex Ingram, Leonid Kinskey. Screenplay: Irwin Shaw, Sidney Buchman, Dale Van Every, Sidney Harmon. Cinematography: Ted Tetzlaff. Art direction: Lionel Banks. Film editing: Otto Meyer. Music: Friedrich Hollaender.

Cary Grant and Ronald Colman The Talk of the Town (1942) dir. George Stevens

836 notes

·

View notes

Text

REBLOG: from dailyworldcinema film THE BLUE ANGEL (1930) (1218)

Whatever can be said about this film, right off the bat, it is a CLASSIC FILM and a historical representation of the moment in film.

The Blue Angel (German: Der blaue Engel) is a 1930 German musical comedy-drama film directed by Josef von Sternberg, based on Heinrich Mann's 1905 novel Professor Unrat (Professor Filth) and set in an unspecified northern German port city.

dailyworldcinema Jun 30 Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel (1930) Dir. Josef von Sternberg

The Blue Angel presents the tragic transformation of a respectable professor into a cabaret clown and his descent into madness.

The Blue Angel - Wikipedia

The Blue Angel (1930) - IMDb 7'7

The English version which is a little hard on the ears and sometimes difficult to understand, however some allowances can be made for a the classic.

LINK https://ok.ru/video/1205418723842

The film was shot simultaneously in German- and English-language versions. Though the English version was once considered a lost film, a print was discovered in a German film archive, restored and screened at San Francisco's Berlin and Beyond film festival on January 19, 2009. The German version is considered to be "obviously superior"; it is longer and not marred by actors struggling with English pronunciation.

NOTES

The film was the first feature-length German sound film and brought Dietrich international fame. It also introduced her signature song, Friedrich Hollaender and Robert Liebmann's "Falling in Love Again (Can't Help It)". The film is considered a classic of German cinema.

I have to admit, I am fascinated by REMAKES.

Remakes, adaptations and parodies 1959 The Blue Angel, director Edward Dmytryk's remake with Curd Jürgens.

link https://ok.ru/video/1843272485445

1966 Pousse-Cafe, a 1966 Broadway musical version with music by Duke Ellington. It was unsuccessful and closed after three performances.

Pinjra (1972), director V. Shantaram's highly successful Marathi/Hindi adaptation with Sandhya and Shreeram Lagoo.

1988 Lola, director Rainer Werner Fassbinder's loose adaptation of the film and its source novel.

1991 The Royal Shakespeare Company produced a stage adaptation, written by Pam Gems and directed by Trevor Nunn, that toured the UK from 1991 to 1992.

1988 In 1998, the Gems adaptation was translated to Japanese. With added songs composed by accordionist Yasuhiro Kobayashi, the Japanese version was staged as a musical starring Kenji Sawada at the Bunkamura in Tokyo.

2001 A stage adaptation by Romanian playwright Răzvan Mazilu premiered in 2001 at the Odeon Theatre in Bucharest, starring Florin Zamfirescu as the professor and Maia Morgenstern as Lola Lola.

2010 In April 2010, Playbill announced that David Thompson was writing the book for a musical adaptation of The Blue Angel, with Stew and Heidi Rodewald providing the score and Scott Ellis directing.

VARIOS: Lola Lola's nightclub act has been parodied on film by Danny Kaye as Fraulein Lilli in On the Double (1961) and by Helmut Berger in Luchino Visconti's The Damned (1969).

REBLOG: from dailyworldcinema film THE BLUE ANGEL (1930)

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Cast: Cary Grant, Ronald Colman, Jean Arthur, Edgar Buchanan, Glenda Farrell, Charles Dingle, Emma Dunn, Rex Ingram, Leonid Kinskey. Screenplay: Irwin Shaw, Sidney Buchman, Dale Van Every, Sidney Harmon. Cinematography: Ted Tetzlaff. Art direction: Lionel Banks. Film editing: Otto Meyer. Music: Friedrich Hollaender.

THE TALK OF THE TOWN (1942) dir. George Stevens

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ich und die Kaiserin (1933), dir. by Friedrich Hollaender

#ich und die kaiserin#conrad veidt#and the party don't start till i walk in#Friedrich Hollaender#sci's gifs#sillay

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marlene Dietrich: Falling in Love Again (Can't Help It)

“Falling in Love Again (Can’t Help It)” is the English language name for a 1930 German song composed by Friedrich Hollaender as “Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt” (literally: “I am, from head to toe, ready for love”). The song was originally performed, in the 1930 film Der Blaue Engel (English translation: The Blue Angel), by Marlene Dietrich, who also recorded the most famous…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Phffft (Mark Robson, 1954)

Cast: Judy Holliday, Jack Lemmon, Jack Carson, Kim Novak, Luella Gear, Donald Randolph, Donald Curtis. Screenplay: George Axelrod. Cinematography: Charles Lang. Art direction: William Flannery. Film editing: Charles Nelson. Music: Friedrich Hollaender.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel still has some of the earmarks of a film made during the transition from silence to synchronized sound, namely the tendency to hold a shot a beat or two longer than is actually necessary, so the narrative doesn't always move along at the speed we anticipate. But Sternberg is clearly ready for sound, as the final scene shows. The camera tracks back from the dead professor, clutching his old desk so tightly that the caretaker who found his body has been unable to loosen his grip. Meanwhile, we hear the clock striking midnight, with the twelfth stroke barely audible as the screen fades to black. It's a touching moment, made possible by the several shots and sounds of the clock that occur through the film as a kind of indicator of Rath's decline from precise and punctual to dissipated and tardy. Otherwise the sound on the film is sometimes a little harsh to the ear, which makes Sternberg's relatively sparing use of it welcome. Many scenes are staged in near-silence, letting the action rather than the dialogue carry the story. Marlene Dietrich's baritone recorded well, which is one reason her career took off when sound was introduced, but early in the film she's allowed to sing in an upper key which is more than a little off-putting. Fortunately, by the time we get to Lola Lola's big number, Friedrich Hollaender's "Ich bin von Kopf zu Fuß auf Liebe eingestellt" (the subtitles use the English language version, "Falling in Love Again" instead of a literal translation), Dietrich is back in the correct register. The Blue Angel thrives on Dietrich's performance, which eclipses Emil Jannings's overacting, though he does provide some genuine pathos toward the end of the film. I don't quite believe the ease with which the professor falls from grace, but I'm not sure whether the fault lies entirely with Jannings or with the screenplay.

Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel (1930) Dir. Josef von Sternberg

765 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Raus mit'n Männern aus'm Dasein Und raus mit'n Männern aus'm Hiersein Und raus mit'n Männern aus'm Dortsein Sie müssten längst schon fort sein Ja, raus mit'n Männern aus'm Bau Und rin in die Dinger mit der Frau

#oh friedrich hollaender we're really in it* now#*clever wordplay#claire waldoff#german stuff#friedrich hollaender

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Blue Angel (1930, Germany)

With the silent era at its conclusion and the rise of Nazism upcoming, German cinema’s brief early sound era shows the visual mastery of what might have been. The Blue Angel is Germany’s first feature-length synchronized sound film and is helmed by Austrian-American Josef von Sternberg in his only German-language production. Von Sternberg had directed a handful of films for Paramount prior to The Blue Angel, including The Docks of New York (1928) and The Last Command (1928). Thematically, The Blue Angel – produced by Universum Film AG (UFA) and distributed in the United States by Paramount – is a departure from von Sternberg’s previous films, while also adopting the aesthetic influences of German expressionism. In these precious few years following the heights of German silent film glory, the audience is treated to a talkie that always feels like a silent film. That incongruity never distracts, and only serves to demonstrate how remarkable The Blue Angel is in an experimental period of filmmaking – a period where few filmmakers could balance the needs of image and sound.

In Weimar Germany, disciplinarian professor Immanuel Rath (Emil Jannings) is the target of pranks and barbed words from his students at an all-male college prep school. One day, he is particularly annoyed by the boys passing around photographs of cabaret performer Lola Lola (Marlene Dietrich). Lola performs at a local nightclub called The Blue Angel, and Rath visits in hopes to catch his students there. His students are present, but Rath is overcome by lust after watching Lola perform. Returning the next night with a pair of her panties (that one of his students smuggled into his pocket), he spends the night with her. Rumors spread like the flu, Rath is dismissed from his professorship, and allows himself to be humiliated for what he thinks is love. His downfall is sealed.

The Blue Angel is a tragedy, but has more to do with Greek drama than Shakespeare – the former emphasizes the inescapability of divine fate and the role of human hubris in believing predestination can be overcome; the latter is dictated on the free will of an individual and how their character flaws result in their demise (the flaw need not be hubris, but it is often invoked by Shakespeare). According to von Sternberg, The Blue Angel is making no attempts at political allegory, so his intentions are purely personal. As Rath, Jannings plays his character as a rebuke to the besotted silent film romances seen across Western cinema. Unlike Heinrich Mann’s novel on which this film is based on, The Blue Angel never allows Rath to change himself over the course of his relationship with Lola. Maybe the audience should have sensed this earlier: his personality, his sense of order in the classroom was of strict control. Believing in his intelligence and ability to control his emotions and the situation, he stumbles upon Lola, holding her up to an image of perfection, and believing in that image steadfastly until he finally sees otherwise.

As the film’s seductress, Lola is a charismatic fantasy that men desire (permit some heteronormative language in respect to what the film depicts). But what people desire and what they need are distinct – something that neither Rath nor Lola ever understand. In her introductory scene, Lola is performing onstage, essentially opening herself to the unprocessed feelings of lustful men (young and old). She purrs, “... I have a pianola / that is my joy and pride. / They call me naughty Lola; / the men all go for me. / But I don’t let any man / lay a paw on my keys.”

What does Lola see in Rath that makes her want to be with him? They marry and it is implied that they become intimate. Her side of the relationship alternates between fits of passion and vitriol; intimacy and unfaithfulness; attention and apathy. Amid a society where cabaret performers like Lola could be seen as flighty and licentious, in Rath Lola sees someone who thinks otherwise. But instead of attempting to understand Lola’s anxieties and weaknesses – the viewer senses that, beneath her erotic public performances, there is more to this character that is never depicted – Rath views her as a romantic nonpareil. His ability for critical thought disappears when it comes to this sort of relationship he might never have experienced; his ability for self-reflection tainted by an unbending, stern, studious approach to his students. For her, Rath presents an opportunity to be accepted as something magnificent, something pure that which she nor anyone ever will be.

The film’s sensitivities are with Rath, not Lola. Even in Rath’s most despicable moment, von Sternberg and fellow co-screenwriters Carl Zuckmeyer, Karl Vollmöller, Robert Liebmann ensure that The Blue Angel remains within the tradition of Greek tragedy (with a twist). Where in the original novel Rath embarks upon exacting revenge against the authoritarian society that has shaped his interactions with students, there is no such redemption here. Rath is punished for his dangerous lustfulness – as he should be. Curiously, the predatory Lola – despite becoming a victim of attempted violence in the final minutes – escapes punishment of any type. In Rath’s tragedy, she has discarded what she no longer wants and has gained something/someone she presently desires. No remorse is present, nor does there appear to be any emotional trauma from ending her relationship with Rath. Perhaps the audience should have expected this, given the lyrics to the memorable “Falling in Love Again”, sung by Dietrich twice with music by Friedrich Hollaender and lyrics by Robert Liebmann (these lyrics are from the English-language version of this song; Hollaender adjusted the songs to accommodate Dietrich’s limited, but effective, vocal range):

Love's always been my game, Play it how I may, I was made that way, Can't help it.

If The Blue Angel had been produced primarily in the United States later in the 1930s, this ending could not have been upheld by the censors. Love (or romance or whatever you wish to call it), to Lola, is a fun game to play. And playing by her rules, she has always won. Where Rath experiences a tragedy befitting a German expressionist protagonist, Lola’s inconclusive fate feels contemporary regardless of the film’s Weimar morals.

The film collapses without the performances from its two central stars. Before release, Jannings was the lead if one looked at the billing. He had just won the inaugural Academy Award for Best Actor in von Sternberg’s The Last Command and 1927′s The Way of All Flesh (actors were listed for multiple movies at the first Oscars) – this film was to be his nominal pinnacle. Jannings excelled in playing tortured, disgraced characters and could do no greater here with his physical acting. His performance would be just as spellbinding if The Blue Angel was a silent film. However, Jannings is upstaged by Dietrich the moment she appears on-screen. Dietrich, playing an intemperate woman, became an instant sensation to European and American audiences in this, her twentieth film (and first talkie). But her success in The Blue Angel also served to typecast Dietrich into roles unscrupulous and indiscreetly erotic – pursuing sexual satisfaction at the expense of others’ needs. Von Sternberg doted on Dietrich during production, sparking the ire of Jannings (who entered production hoping to become next Hollywood star, but instead saw his career plummet afterwards due to his heavy German accent and subsequent work Nazi propaganda films) and von Sternberg’s wife (who filed for divorce after the film’s release). Her sensuality defined this film, whether or not the cameras rolled.

Manning the cameras was veteran cinematographer Günther Rittau (Die Nibelungen saga, 1927′s Metropolis). Rittau captures the smoky interior of The Blue Angel nightclub and the seedy nighttime of this unnamed German town to convey a sense of enclosure. Art director Otto Hunte (Die Nibelungen saga, Metropolis) employs distorted geometries – early shots of angled rooftops and jagged roads primes the imagination for the unconventional story to come – and exaggerated shapes and lighting to assist Rittau in achieving the film’s wondrous atmosphere.

This film, like many in the early years of synchronized sound, was shot in two different languages – German and English (yes, the actors had to shoot every seen and recite their lines twice). The above has been written based on the 107-minute uncut German-language version distributed by Kino International, licensed by the Murnau Foundation, and aired on Turner Classic Movies (TCM). Consensus says that the German-language version is superior to the English edition.

Predictable though it might be, The Blue Angel is a forceful statement of German filmmaking – it is a film honoring the expressionist past while showcasing its future (a future where many of its innovators would flee the Nazis and work in Hollywood). It would also be one of UFA’s final classics – the studio also released Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924), and Fritz Lang’s visionary Metropolis. Von Sternberg’s film, reflecting the drama behind the cameras, is a romantic tragedy that sings of love even when its characters know little about it. The Blue Angel is a triumph that quickly became written into German cinematic history. Its rapid ascent into that history can be attributed to the political changes soon to uproot all that German filmmakers had nourished. This film could not have been made any better in any other time.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#The Blue Angel#Josef von Sternberg#Emil Jannings#Marlene Dietrich#Kurt Gerron#Rosa Valetti#Hans Albers#Reinhold Bernt#Eduard von Winterstein#Gunther Rittau#Otto Hunte#Friedrich Hollaender#Robert Liebmann#Carl Zuckmayer#Karl Volllmoller#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Angel (Ernst Lubitsch, 1937) Cast: Marlene Dietrich, Herbert Marshall, Melvyn Douglas, Edward Everett Horton, Ernest Cossart, Laura Hope Crews, Herbert Mundin, Dennie Moore. Screenplay: Samson Raphaelson, Guy Bolton, Russell G. Medcraft, based on a play by Melchior Lengyel. Cinematography: Charles Lang. Art direction: Hans Dreier, Robert Usher. Film editing: William Shea. Costume design: Travis Banton. Music: Friedrich Hollaender.

In Ernst Lubitsch’s Angel, you can almost feel the Production Code censors breathing hotly down the director’s neck, driving some of the oxygen out of the room. What’s meant to be a light and airy sophisticated comedy, like for example Lubitsch’s pre-Code masterpiece Trouble in Paradise (1932), often feels starchy and coy. The emigrée grand duchess played by Laura Hope Crews is clearly a high-class procuress and her “salon” a very upscale brothel that enables a “fling” by Lady Maria Barker (Marlene Dietrich) with a curiously naïve Anthony Halton (Melvyn Douglas). Their affair never seems to get consummated, although there are the usual narrative jumps when the relationship comes to the boiling point. And of course the Code’s aversion to divorce and abhorrence of any sign that adulterers might get away with it unpunished means that the film must end with Lady Maria and Sir Frederick (Herbert Marshall) happily reconciled. We’re used to such evasions in Hollywood movies of the 1930s through the 1950s, but it’s a little depressing to see them stifle Lubitsch’s usually sublime naughtiness. Sometimes it feels as if Dietrich is to blame: She never really strikes sparks with either Douglas or Marshall – certainly not the way Greta Garbo does with Douglas in Ninotchka (1939) or Miriam Hopkins with Marshall in Trouble in Paradise. But lovers of Lubitsch have plenty to enjoy in Angel, chiefly the way the director subverts expectations. When Sir Frederick invites Halton, an old war buddy, to dine with him and his wife, who neither man knows is the “Angel” Halton met in Paris and has been rhapsodizing about ever since, we expect a big explosion, especially when the husband points out his wife’s picture to her lover. But just as Halton is about to look at the photograph, Lubitsch cuts. We don’t see the awkward encounter between wife and lover we expect when she comes downstairs to meet the guest. Instead, we pick up with them later and realize that both have exerted exceptional self-control at the meeting. And we don’t see the three of them at the dinner table; instead, Lubitsch takes us into the kitchen, where the servants are wondering why neither Lady Maria nor Mr. Halton has touched their food. Lubitsch leaves to our imagination scenes that other directors would have milked shamelessly. In another example, at their first encounter Maria and Halton are in a Parisian park at night, and after he proclaims his love for her he spots an old woman selling violets. He goes to buy the flowers, but Lubitsch holds the camera on the old woman, whose expressions tell us what’s going on: Maria has chosen the moment to disappear and we hear Halton calling out “Angel!” in his pursuit of her. The flower seller sighs and picks up the dropped bouquet, dusts it off, and puts it back with the other flowers, then turns and walks away. Similarly, Lubitsch doesn’t linger on the reconciliation scene between Maria and Frederick: They simply walk out the door, headed for Vienna and what we hope is a revived marriage. In the end, these “Lubitsch touches” aren’t quite enough to lift Angel out of the middle tier of the director’s films, but they constitute its saving grace notes.

gifs from gingerastaire

296 notes

·

View notes