#Flora & Curl

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

BETH·S hair: nueva tienda con productos para el método curly en Zaragoza.

BETHS. Tu nueva tienda con productos aptos para el método curly en Zaragoza Hola, Curly. Ya sabes, que siempre estoy pendiente de las novedades. No solo, de los nuevos productos para el cabello afro rizado, que llegan al mercado. También de la abertura de nuevas tiendas donde los podéis comprar. Por lo que, hoy te traigo una buena noticia. Ya que, justamente, ayer descubrí una tienda,…

View On WordPress

#as iam mascarilla#beths hair#cantu#Flora & Curl#kinky curly#Lola Cosmetic#metodo curly#shea moisture#tienda productos cabello rizado

0 notes

Text

OC Lore Post

Since someone in the "anyone can art" community asked, for those who don't follow this blog, I'll give y'all a quick rundown of Crystalla's lore since she's got stuff goin' for her.

SOME OF THE STUFF MENTIONED HERE MAY BE RATHER SENSITIVE, SO DON'T CLICK READ MORE IF YOU FEEL OFFENDED.

Crystalla and her family are part of a species called "Ge-Ants", alien-like humanoids that live in a recolonized Earth set 1200 years into the future, after the humans had basically gone extinct. Ge-Ants have antennas on their heads that allow them to make sense of their direction around the world, directing them where they need to go most of the time. A bit like compasses (and GPS, if you will)! Their antennas can also bend to their will, contorting and extending, or even shrinking and growing!

As for Crystalla herself, she had spent most of her infancy learning about biology; fauna, flora, climate, all of that stuff. When her dad, Blizzo, arrived from work, he'd spend time playing with Crystalla and teaching her to play the violin; he was a musician, after all! Young Crystalla wished she'd be as good as a musician as her father when she grew up. Blizzo would also bring toys for her sometimes!

This is Blizzo, by the way. A tad bit of a grump here, but he was mostly quite chill when he was alive.

Crystalla also has a sister and mother, both of which were rather supportive of Crys in elementary and high school! Glacy is a librarian, a rather avid one at that.

However, what Crystalla and Glacy did NOT expect was the rather strange change in Blizzo's behavior; during Crys' time in high school, Blizzo would often wake up rather agitated, sometimes refusing to greet others with a good morning, good evening or afternoon. Worst, he'd slam doors shut fiercely without bothering to apologize!

...All of this came to a head when Crystalla was in 3rd grade; Blizzo would inflict heavy mental abuse AND verbal abuse upon poor Crystalla, sometimes even PHYSICAL abuse. It got SO BAD one day that, having no other option, Crystalla and Frostia decided to pack things up and move to a new household, which they still live on today. Glacy was so appalled by this whole ordeal that she decided to report to the authorities, and after a court session, Blizzo was sentenced to 2 years in prison.

A few years after Crystalla graduated university and started pursuing a job as a biology teacher, Blizzo had suffered a tragic death due to a car accident; no one knows how he managed to get out of prison, but Crystalla still feels horrified by all of the stuff he did, having looked up to Blizzo as sort of an "idol" during her infancy and to see him stoop so low breaks her heart.

-----

Moving on from this, Crystalla has a power-up form called Frostbliss Crystalla which she gets through using the power of the "Frozen Scepter", a magical artifact said to having been discovered by humans a few years before their extinction. This magical scepter gives an upgrade to Crystalla's abilities, which get amped up ten-fold, and gives her a long scarf-cape hybrid. Her skin darkens and her hair gets longer, curling up and gaining light cyan stripes.

If, however, she happens to lose the Frozen Scepter at any point or exert her powers a bit too much, she'll return back to normal. Therefore, this form should be used with caution.

-----

Okay yeah I think that's enough yapping for now AKSKEUDIKSNSLSNDBUEV,,,

SIKE, here's an update with Danny Wind!

Danny Wind Blister, current age of 23, had been made an orphan at about only 5 years old after his biological father and mother got into a heavy disagreement. A few months after, he had been adopted by a wealthy lady who promised to take great care of him and raise him better than his old parents did.

At the age of 10, Danny started training his wind powers, but got told by his mother that if he made too much use of them, he'd get really worn down, but had the determination to keep learning about and managing his own powers.

Growing up, Danny Wind started taking fascination toward the prehistoric eras by watching documentaries and videos online about dinosaurs, something that Danny admired a lot. Danny is also a close friend of Crystalla and, like her, took a liking to nature and biology, studying all aspects of flora and fauna during elementary school, interspersed by his wind power training sessions.

He valued his studies as much as he valued his wind powers, so much so that by 2nd grade of high school he was considered the smartest student out of his entire classroom! Danny and Crystalla met sometime around 3rd grade, both having studied in different classes in the same school.

Danny back then had no idea what Crystalla was going through, but he hoped he could support whatever her cause was. Crystalla one day gave Danny her contact number so they could chat during the weekends, and only then did Dan find out about the abuse Crys' father was inflicting on her, being morbidly horrified at the fact.

Danny's fascination of prehistoric stuff eventually led him to taking a paleontology course in the Woodstraw University; nowadays he spends his time hanging out with Crystalla and Frostia, reading books and playing video games.

#josh's ocs#crystalla#frostia#glacy#blizzo#my art#josh's art#digital art#digital artist#artists on tumblr#art#artwork#my ocs#ocs#oc art#oc artwork#original characters#doodles#oc stuff#autistic artist#oc lore#oc lore dump#oc lore stuff#lore drop#lore dump

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary: Lloyd and Morro get stuck.

Warnings: They're probably out of character because I'm really tired rn.

Prompt: Day 8 - Travel | Realm

Extra: Basically, Lloyd and Morro begrudgingly work together to get the Realm Crystal back. Takes place while Lloyd and Morro are dimension hopping in the Season 5 finale.

Lloyd and Morro got spat out of another portal, and Lloyd swung his leg in a desperate effort to get the Realm Crystal.

Clngg!

The two glanced at each other, the abnormally large gem glistened on the rocky ground, just out of reach. The pair scrambled to grab it before each other, limbs thrashing in an effort to beat the other.

Lloyd's hand reached towards the crystal, and-

Morro dragged him back by his ankle, using it as momentum to propel him forwards.

Only for a fucking bird to snatch it.

"What the- OH COME ON!" Lloyd groaned.

Morro launched into the air in hot pursuit of the bird, Lloyd just a beat behind him using Airjitzu.

The stupid feathered thing darted around, as if playing a game with the green-themed people.

A cliff came up ahead, and the bird folded its wings into a dive. Lloyd landed on the edge as the ghost sped over, using his wind powers to push himself faster.

The blonde peered over the edge warily, watching Morro chase aggressively after the avian thief. Eventually, the two went far enough away that it was difficult even for Lloyd's hybrid eyes to see, so he-

Hesitated.

Was he really about to jump off a cliff in a realm he's never been in before? What if gravity worked differently? He took a deep breath, and then jumped off the cliff.

Lloyd focused, intentionally avoiding the fact that he was falling to his possible death ohmyFirs- and summoned his elemental dragon. He swiftly glided after the ghost and the bird.

Speaking of the two, Morro yelled outdated profanities at the avian creature as the two disappeared into the flora.

"You bescumbering wretch!"

Lloyd faltered, unsure what "bescumbering" meant. He shook his head, that is a question for later. He nudged his dragon to hurry, and it obeyed.

He dove into the first opening he could find into the plume of orangey leaves. There, he spotted Morro standing on a tree(?) branch as he glared above him.

Lloyd desummoned his dragon as he stuck the landing next to the ghost.

Standing next to Morro somewhat made his skin crawl. Maybe it's from the possession, or it's just a ghost thing.

"Whatcha glaring at?" Lloyd asked. It felt weird to be casual with Morro. The blonde really needed to find out where the Realm Crystal went, but why would Morro tell him where-

"That... fopdoodle of a bird is hiding up there," Morro growled.

The younger snorted. Fopdoodle? Really? That's such a weird word.

"Oh ha ha. Laugh it up. You wanna go get the Realm Crystal? Be my guest," Morro looked dead serious.

...oh my FSM.

Lloyd cracked up more, staring to full on wheeze and he clutched his stomach and curled forwards.

Morro's anger seemed to have amped up alongside his confusion. "What are you even laughing at, you fribble?"

Lloyd fucking cackled. "What-" cut off by giggling, "the h-hell is a fribble?"

He resumed his cackling, his balance swayed as he risked falling off the branch multiple times.

The blonde slowly came down from his giggling high as the gears in Morro's brain turned.

"...oh," was all he said once it clicked.

"Oh, what?" Lloyd questioned.

Morro sighed ,"I've been using really old slang this entire time."

Lloyd gaped, "Wait, that's what that was? I thought you were just saying gibberish!"

"...why in all of the 16 realms would I say gibberish?" Morro squinted at the younger.

"I- uh- well sometimes Jay does, so I usually chalk up weird non-scientific words to just be random gibberish."

Morro looked 2 seconds away from punching someone. Probably me, Lloyd realized and slightly shifted away from the ghost.

"So, uh- where did the Realm Crystal go?" Lloyd asked.

Morro glared at the teen before reluctantly pointing upwards. "That imbecilic bird's hiding with it, and whenever you go near it the thing either tries to bite you or poop on you."

"...ohhhkayyy. Is that what- uhh, what was the word- oh yeah, is that what 'bescumbering' means?" Lloyd asked.

Morro gave Lloyd a look. "The latter."

Silence blanketed the two.

"Uhh, sooooo. How are we- ew, that felt weird to say- going to get the Realm Crystal back?"

"Who said we were going to get it back? I will get it back and leave you here so I can-"

"-conquer Ninjago beside my Master, I know. You've given thise speech before, Breezy, no need to repeat yourself for the thousandth time," Lloyd rolled his eyes.

Morro used a gust of wind to shove him off the branch. Lloyd yelped before a soft 'thud' enunciated his landing onto the forest-like floor.

"Rude," Lloyd muttered before jumping at the sight of Morro as he crashed next to him. Said ghost looked done with everything.

"As stubborn as I am, I will admit that I..." Morro's words trailed off into a low enough voljme that Lloyd couldn't hear him.

"Uhh, what?" he asked.

"I-" Morro sighed angrily, "I need your help."

"Huh?"

"I said I need your help, damnit!"

"I know, I heard you the second time," Lloyd had a smug grin painted on his features, until Morro shoved a bunch of leaves into his face via the wind.

"So, what's the plan, oh 'great Green Ninja'," Morro snarked.

"Well, we need to figure out where the crystal is first, so we can get it."

"The bird's sitting on it."

"Well that's- a problem. But at least we know where it is!...

Wait, how do you know that?"

"The wind. And the fact that, before it tried to bite me I saw it underneath the bird."

"Wait, you're a ghost. Why don't you just possess the bird?"

"..." Morro facepalmed. "How the fuck did I not think of that."

"Well then go do it, genius!"

"Shut up, fribble."

"What's a fribble???"

Morro shot up to the bird before Lloyd could get an answer.

A loud squawk, flapping noises, a grunt, and the ghost landing on the ground again suggested-

"It didn't work."

"Yeah, I guessed so after the offended squawk."

"So what next?"

"Uhh, decoy and thief?"

"One gets shat on while the other steals? Sure."

"Alright, then who-"

"You're getting shat on."

"Wha- WHY ME?"

"Because I said so, and poop has water content."

"Does that mean I could kill you with poop?"

"Not before I suffocate you to death."

The two climb up the tree, and Lloyd starts bugging the bird as Morro creeped up in the bird's blind spot.

Hey, this is going to well-

"ACK! IT BIT ME!"

And there it is.

Morro snagged the gem, but before he could portal away-

"Duck!"

The bird fucking shat.

Lloyd darted towards Morro, and activated the Realm Crystal.

Now back to our regularly scheduled "Lloyd Fight's His Abuser/Trauma Giver TM".

-

If you couldn't tell by the end, it's like 1:41 am and I'm tired.

#ninjago#morro ninjago#morro#morro master of wind#morrotober#ninjago morro#morrotober 2023#lloyd ninjago#lloyd garmadon#morro wu#ninjago possession#ninjago season 5#look i'm sorry this was so late 😭#i was balancing this plus my homework#and i have a thing worth 70% of my grade due tomorrow#so that's fun 😃#anyways i might upload another au later idk#also let morro swear#also also bescumber means to spray poo#fopdoodle essentially means simpleton#and fribble means “good-for-nothing fellow”#if i remember correctly#old slang/insults are so funny

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

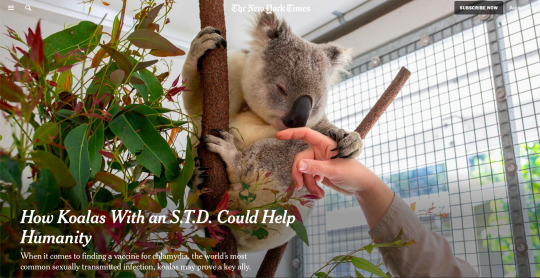

How Koalas With an S.T.D. Could Help Humanity

When it comes to finding a vaccine for chlamydia, the world’s most common sexually transmitted infection, koalas may prove a key ally.

Skroo, a wild koala visiting Endeavour Veterinary Ecology clinic, on June 25. Researchers at the clinic are testing a vaccine against chlamydia in koalas, which is very similar to the human form of the disease.Credit...Russell Shakespeare for The New York Times

By Rachel E. Gross

July 13, 2020

The first sign is the smell: smoky, like a campfire, with a hint of urine. The second is the koala’s rear end: If it is damp and inflamed, with streaks of brown, you know the animal is in trouble. Jo, lying curled and unconscious on the examination table, had both.

Jo is a wild koala under the purview of Endeavour Veterinary Ecology, a wildlife consulting company that specializes in bringing sick koala populations back from the brink of disease. Vets noticed on their last two field visits that she was sporting “a suspect bum,” as the veterinarian Pip McKay put it. So they brought her and her 1-year-old joey into the main veterinary clinic, which sits in a remote forest clearing in Toorbul, north of Brisbane, for a full health check.

Ms. McKay already had an inkling of what the trouble might be. “Looking at her, she probably has chlamydia,” she said.

Humans don’t have a monopoly on sexually transmitted infections. Oysters get herpes, rabbits get syphilis, dolphins get genital warts. But chlamydia — a pared-down, single-celled bacterium that acts like a virus — has been especially successful, infecting everything from frogs to fish to parakeets. You might say chlamydia connects us all.

This shared susceptibility has led some scientists to argue that studying, and saving, koalas may be the key to developing a long-lasting cure for humans. “They’re out there, they’ve got chlamydia, and we can give them a vaccine, we can observe what the vaccine does under real conditions,” said Peter Timms, a microbiologist at the University of Sunshine Coast in Queensland. He has spent the past decade developing a chlamydia vaccine for koalas, and is now conducting trials on wild koalas, in the hopes that his formula will soon be ready for wider release. “We can do something in koalas you could never do in humans,” Dr. Timms said.

In koalas, chlamydia’s ravages are extreme, leading to severe inflammation, massive cysts and scarring of the reproductive tract. In the worst cases, animals are left yelping in pain when they urinate, and they develop the telltale smell. But the bacteria responsible is still remarkably similar to the human one, thanks to chlamydia’s tiny, highly conserved genome: It has just 900 active genes, far fewer than most infectious bacteria.

Because of these similarities, the vaccine trials that Endeavour and Dr. Timms are running may offer valuable clues for researchers across the globe who are developing a human vaccine.

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery

How bad is chlamydia in humans? Consider that around one in 10 sexually active teenagers in the United States is already infected, said Dr. Toni Darville, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina. Chlamydia is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, with 131 million new cases reported each year.

Antibiotics exist, but they are not enough to solve the problem, Dr. Darville said. That’s because chlamydia is a “stealth organism,” producing few symptoms and often going undetected for years.

“We can screen them all and treat them, but if you don’t get all their partners and all their buddies at the other high schools, you have a big spring break party and before you know it everybody’s infected again,” Dr. Darville said. “So they have this long-term chronic smoldering infection, and they don’t even know it. And then when they’re 28 and they’re like, ‘Oh, I’m ready to have a baby, everything’s a mess.’”

In 2019, Dr. Darville and her colleagues received a multiyear, $10.7 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to develop a vaccine. The ideal package would combine a chlamydia and gonorrhea vaccine with the HPV vaccine already given to most preteenagers. “If we could combine those three, you’d basically have a fertility anticancer vaccine,” she said.

Chlamydia’s stealth and ubiquity — the name means “cloak-like mantle” — owes to its two-stage life cycle. It starts out as an elementary body, a spore-like structure that sneaks into cells and hides from the body’s immune system. Once inside, it wraps itself in a membrane envelope, hijacks the host cell’s machinery and starts pumping out copies of itself. These copies either burst out of the cell or are released into the bloodstream to continue their journey.

“Chlamydia is pretty unique in that regard,” said Ken Beagley, a professor of immunology at Queensland University of Technology and a former colleague of Dr. Timms. “It’s evolved to survive incredibly well in a particular niche, it doesn’t kill its host and the damage it causes occurs over quite a long time.”

The bacterium can hang out in the genital tract for months or years, wreaking reproductive havoc. Scarring and chronic inflammation can lead to infertility, ectopic pregnancy or pelvic inflammatory disease. Evidence is mounting that chlamydia harms male fertility as well: Dr. Beagley has found that the bacteria damages sperm and could lead to birth abnormalities.

All of this — except the spring break parties — is true in both humans and koalas. Researchers who work with both species note that koala chlamydia looks strikingly similar to the human version. The main difference is severity: In koalas, the bacterium rapidly ascends the urogenital tract, and can jump from the reproductive organs to the bladder thanks to their anatomical proximity.

These parallels have led Dr. Timms to argue that koalas could serve as a “missing link” in the search for a human vaccine. “The koala is more than just a fancy animal model,” he said. “It actually is really useful for human studies.”

An ancient curse

No one knows how or when koalas first got chlamydia. But the curse is at least centuries old.

In 1798, European explorers reached the mountains of New South Wales and spied a creature that defied description: ear-tufted and spoon-nosed, it peered down stoically from the crooks of towering eucalyptus trees. They compared it to the wombat, the sloth and the monkey. They settled on “native bear” and gave it the genus name Phascolarctos (from the Greek for “leather pouch” and “bear”), spawning the misconception that the koala bear is, in fact, a bear.

“The graveness of the visage,” The Sydney Gazette wrote in 1803, “would seem to indicate a more than ordinary portion of animal sagacity.”

In the late 19th century, the Australian naturalist Ellis Troughton noted that the “quaint and lovable koala” was also particularly susceptible to disease. The animals suffered from an eye ailment similar to pink eye, which he blamed for waves of koala die-offs in the 1890s and 1900s. At the same time, the anatomist J.P. Hill found that koalas from Queensland and New South Wales often had ovaries and uteruses riddled with cysts. Many modern scientists now believe those koalas were probably afflicted with the same scourge: chlamydia.

Koalas today have even more to worry about. Dogs, careless drivers and, recently, rampant bushfires have driven their numbers down so far that conservation groups are calling for koalas to be listed as endangered. But chlamydia still reigns supreme: In parts of Queensland, the heart of the epidemic, the disease helped fuel an 80 percent decline over two decades.

The disease is also the one that most often sends koalas to the Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital, the country’s busiest wildlife hospital, located 30 miles north of Endeavour. “The figures are 40 percent chlamydia, 30 percent cars, 10 percent dogs,” said Dr. Rosemary Booth, the hospital’s director. “And then the rest is an interesting assortment of what trouble you can get into when you have a small brain and your habitat’s been fragmented.”

Dr. Booth’s team treats “chlamydia koalas” with an amped-up regimen of the same antibiotics used on humans. “I get all of my chlamydia information from the C.D.C.,” she said, referring to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the United States, “because America is the great center for chlamydia.”

But the cure can be as deadly as the disease. Deep inside a koala’s intestines, an army of bacteria helps the animal subsist off eucalyptus, a plant toxic to every other animal. “These are the ultimate example of an animal that’s completely dependent on a population of bacteria,” Dr. Booth said. Antibiotics extinguish that crucial gut flora, leaving a koala unable to gain nutrients from its food.

In a 2019 trial led by Dr. Timms and Dr. Booth, one of five koalas treated with antibiotics later had to be euthanized “due to gastrointestinal complications, resulting in muscle wasting and dehydration.” The problem is so dire that vets give antibiotic-treated koalas “poo shakes” — fecal transplants, essentially — in the hopes of restoring their microbiota.

For the past decade, Dr. Timms has worked to perfect a vaccine. Rather than treat animals once they are already sick, a widespread vaccine would protect koalas from any future sexual encounter and from passing the infection from mother to newborn. His formula, developed with Dr. Beagley, appears to work well: Trials have shown that it is safe to use and takes effect within 60 days, and that animals show immune responses that span their entire reproductive lives. The next step is optimizing it for use in the field.

At Endeavour, the vets treating Jo got a surprise: Molecular tests showed she was chlamydia-free. That meant she could be recruited for the current trial, which is testing a combined vaccine against chlamydia and the koala retrovirus known as KoRV, a virus in the same family as H.I.V. that similarly knocks down the koala’s immune system and makes chlamydia more deadly.

Dr. Timms is hoping that this trial and another in New South Wales will be the “clincher” — the last step before the government rolls out mass vaccinations. If he is right, it could be good news for more than just koalas.

Of mice and marsupials

Dr. Timms began his career studying chlamydia in livestock before moving on to using mice as a model for a human vaccine. Cheap, plentiful and amenable to genetic manipulation, mice have long been the gold standard for studying reproductive disease.

But the mouse model comes with serious drawbacks. Most glaringly, mice exhibit a profoundly different immune response to chlamydia than ours, making the idea of testing a mouse for a human vaccine “completely flawed,” Dr. Timms said.

After a decade of doing mouse work, he reasoned that he could take the insights he had gleaned and apply them to an animal that was actually suffering and possible to cure: the koala. “We don’t need a vaccine for mice,” he said. With “koala work, as hard as that is, and as difficult as that is, the results you get are the ones that matter.”

The more Dr. Timms worked with koalas, the more he realized that these marsupials were not so different from you and me. Here was a species that, like us, was naturally infected with several strains of chlamydia and suffered from similar reproductive outcomes, including infertility. He realized he might have a useful model animal on his hands.

“You’re better off doing a bad experiment in koalas than a good experiment in mice,” Dr. Timms said. “Because koalas really do get chlamydia and they really do get reproductive tract disease, so everything you do is relevant.”

Outside Australia, many researchers say the idea of a koala model is clever but difficult to implement. Dr. Darville pointed out that it would be expensive and logistically impossible to test 30 different vaccines in koalas. (According to Endeavour, it costs roughly $2,000 to pluck one koala from its tree and give it a health exam.)

Still, Dr. Timms said, the challenge was worth attempting: “The reason that we’re making a case that in between mouse and humans you should put koalas — rather than guinea pigs, minipigs and monkeys — is that koalas address all of the weaknesses, to some degree, that the others have.”

Paola Massari, an immunologist at Tufts Medical School, is collaborating with Dr. Timms to test a different potential vaccine in koalas. “The koala represents a perfect clinical model, because it’s an animal for which you can do some experimentation that’s a little more than what you can do in humans,” she said. “And at the same time, if you get results, you are curing a disease (in koalas).”

An unlikely alliance

On a hot February afternoon, Dr. Booth strode out into the blaring sunlight of the Australia Zoo grounds. She was heading to the chlamydia wards, which in 2018 were officially named the John Oliver Koala Chlamydia Ward after a grant was donated on the comedian’s behalf. About 20 sick koalas were being treated with antibiotics that day, with dozens more on the road to recovery.

Dr. Booth stepped up to a leafy enclosure, where a fluffy gray female eyed her curiously from her perch. This koala was originally brought in for chlamydia but had since recovered; her reason for being here, listed on her cage, was “misadventure.”

“This is little Lorna, who’s rather interesting,” Dr. Booth said. “She has a baby in her pouch and she’s had problems with her glucose metabolism” — she had diabetes.

Wasn’t it unusual to have an animal that gets such humanlike diseases: diabetes, cancer and sexually transmitted infections? “We are but an animal,” Dr. Booth said, throwing her hands up in a gesture of unity with the world. “We didn’t think of it first.”

It is still uncertain to what extent the research on koala chlamydia will help in developing a human vaccine. (Dr. Darville had been working for nine months when Covid-19 hit, shuttering her lab and slowing scientific progress.) What is certain is that the research done on human chlamydia has greatly benefited koalas. From human antibiotics to mouse insights, wildlife veterinarians have far more tools than before to save the vulnerable marsupials.

For Dr. Booth, helping koalas is more than enough. “I don’t want to save humans,” she said. “My emphasis is completely the other way: I want to use human research to help save other animals. Because they don’t have a voice unless we speak for them.”

0 notes