#FICTION: A Farewell to Evangelion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

tumblr

FICTION: A Farewell to Evangelion featuring music by JAPANESE BREAKFAST and GORILLAZ

FULL VIDEO

Uncompressed Download

#Evangelion#AMV#Neon Genesis Evangelion#Rebuild of Evangelion#NGE#FICTION: A Farewell to Evangelion#Gorillaz#Japanese Breakfast#video#anime music video#SpaceSweeperUncut#Gainax#Khara#Evangelion Complex

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Evangelion 3.0+1.0,' 'BELLE,' 'JUJUTSU KAISEN 0,' Nominated for Japan Academy Film Prize for Animation of the Year

The 45th Annual Japan Academy Film Prize, Japan's top award show for domestic Japanese films, announced their nominees today for the award show's top categories, including Picture of the Year, Animation of the Year, Director of the Year, all the actor categories, and more, revealing that Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time is competing against JUJUTSU KAISEN 0 for Animation of the Year, which Demon Slayer -Kimetsu no Yaiba- The Movie: Mugen Train won last year.

Picture of the Year

God of Kinema

Last of the Wolves

Under the Open Sky

Drive My Car

In the Wake

Animation of the Year

Sing a Bit of Harmony

Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko

JUJUTSU KAISEN 0

Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time

BELLE

Director of the Year

Kazuya Shiraishi (Last of the Wolves)

Takahisa Zeze (In the Wake)

Miwa Nishikawa (Under the Open Sky)

Izuru Narushima (A Morning of Farewell)

Ryusuke Hamaguchi (Drive My Car)

Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role

Takeru Satoh (In the Wake)

Masaki Suda (We Made a Beautiful Bouquet)

Hidetoshi Nishijima (Drive My Car)

Tori Matsuzaka (Last of the Wolves)

Koji Yakusho (Under the Open Sky)

Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role

Yuki Amami (Rogo no Shikin ga Arimasen!)

Kasumi Arimura (We Made a Beautiful Bouquet)

Mei Nagano (And, the Baton Was Passed)

Mayu Matsuoka (Kiba: The Fangs of Fiction)

Sayuri Yoshinaga (A Morning of Farewell)

Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role

Hiroshi Abe (In the Wake)

Ryohei Suzuki (Last of the Wolves)

Shinichi Tsutsumi (The Fable: A Hitman Who Doesn’t Kill)

Taiga Nakano (Under the Open Sky)

Nijiro Murakami (Last of the Wolves)

Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Supporting Role

Satomi Ishihara (And, the Baton Was Passed)

Kaya Kiyohara (In the Wake)

Mitsuko Kusabue (Rogo no Shikin ga Arimasen!)

Nanase Nishino (Last of the Wolves)

Suzu Hirose (A Morning of Farewell)

Outstanding Foreign Language Film

Tailor (Greece)

Nomadland (United States)

Minari (United States)

No Time to Die (United Kingdom)

Dune (United States)

Newcomer of the Year

Mio Imada (Tokyo Revengers) NOTE: Live-action film

Nanase Nishino (Last of the Wolves)

Touko Miura (Drive My Car)

Ai Yoshikawa (Honey Lemon Soda)

Hayato Isomura (A Family) / (What Did You Eat Yesterday? The Movie)

Ukon Onoe II (Baragaki: Unbroken Samurai)

Hio Miyazawa (Kiba: The Fangs of Fiction)

Fukase (Character)

While not every film or actor is a winner, everyone who is nominated will be given an Award for Excellence, which also includes a statue. The awards will be given out on March 11 in a ceremony at Grand Prince Hotel New Takanawa in Tokyo.

Source: Oricon

----

Daryl Harding is a Japan Correspondent for Crunchyroll News. He also runs a YouTube channel about Japan stuff called TheDoctorDazza, tweets at @DoctorDazza, and posts photos of his travels on Instagram.

By: Daryl Harding

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re-Watching: Angel Beats, Episode 13

No that’s fine I didn’t need my heart today why do you ask FUCK ME I LOVE THIS SHOW SO FUCKING MUCH

Zenith

The final episode of Angel Beats is the single best finale in anime history.

I’ve been sitting in front of this post for far too long trying to figure out a way to start it, and nothing else feels right. There’s no other way to do justice to the titanic magnitude of “Graduation” than to preface my discussion of it with the unblemished, indisputable truth. Angel Beats has my favorite final episode of all time. It’s better than FMAB’s promised day, ranking second only to Asuka’s breakdown in Evangelion episode 22 as my favorite overall anime episode, period. It’s better than Evangelion’s two-part metatextual mindfuck (although maybe not quite better than the movie ending, but that’s a whole different kettle of fish). It’s better than the finale of Jun Maeda’s other masterpiece, Clannad After Story. It tops Hunter x Hunter, Your Lie in April, Cowboy Bebop, Toradora, Wolf’s Rain, Code Geass, Death Note, and any other classic you might throw on the pile. This isn’t just an emotional atom bomb of an episode, it’s the single most concentrated eruption of raw feeling I’ve ever gotten out of a fictional story. It is, no bullshit, the most emotionally cathartic fictional experience I’ve ever had, and it’s the single most important reason behind why Angel Beats ended up as my favorite anime ever. There is nothing in this universe that has made me dissolve into an ocean of tears more consistently than this episode. Even upon re-watch, that remains true; my tears are still drying as I’m writing this post up. It packs a wallop

So let’s break down why Angel Beats’ finale manages to bring the feels so goddamn hard. Because it goes a long way to explaining what makes this show, flaws and all, such an untouchable masterpiece.

The Long Kiss Goodnight

From a structural standpoint, this episode is pretty much nothing but an epilogue. All our characters’ stories have been told, their emotional journeys are complete, and all that’s left is to say goodbye. And that’s what this episode is: one long goodbye to the Afterlife Battlefront and all the time we’ve spent with them. It primes us to bid farewell to the people we’ve spent so much time laughing with, crying with, cheering for and hoping for. That should feel like too much; after all, with no real story left to tell and nowhere left for the characters to go, this episode should really feel overstuffed and overindulgent. But looking at the entire episode from a bird’s-eye view, I’ve realized that’s entirely the point. This episode is too much. It’s too much laughter, it’s too much tears, it’s too much time spent building up to the point when we finally have to goodbye. But that “muchness”, for lack of a more descriptive term, works on you in stages, slowly knocking your defenses down further and further with each successive step on the farewell train. From Yurippe waking up in the hospital to the entire graduation ceremony to everyone vanishing to Otonashi and Kanade’s final conversation, every single step along the journey that is this episode makes us feel the weight of this farewell just a little harder, feel the joy and wonder of what we’re leaving behind that much more palpably.

And that’s why it’s able to hit so fucking hard. Because it just keeps going. It keeps layering on the self-confidently corny symbols of farewell, from the stupid pageantry of the ceremony to Otonashi’s graduating speech to everyone’s personal goodbye to Otonashi’s offer to Kanade to Kanade’s response to that final, agonizing swell of My Most Precious Treasure, and each one makes it harder and harder to hold back the tears. And once they start coming, you never get a break to catch your breath. It just keeps hitting harder and harder, the emotions growing more and more overwhelming, until you’re forced to keel over in a nervous wreck and just let yourself shatter. There’s no escaping the tsunami of empathy and sincerity that washes over you, so your only option is to just accept it into your soul. In this way, Angel Beats achieves yet another impossible feat with this episode; it completely bursts at the seams, and in doing so rises into the pantheon of legend. The density of its storytelling, the willingness to throw caution to the wind and just sprint ahead full-tilt, trusting in its ability to hold together over the bumpiest roads... this is the culmination of everything that makes this show special, the moment where its strengths become too massive and all-encompassing for the fabric of the show to even contain. So it doesn’t even bother trying to contain it, and just lets the emotion pour and pour and pour. And the end result is an overwhelming, rapturous, titanic, even divine experience that sears itself into your memory for all time.

Everything is Awesome

Now, none of that’s to say that there’s nothing of substance to the show’s finale, because that’s clearly not true. The reason this overwhelming emotion works so well is that it’s all based in the same characters and ethos we’ve fallen in love with over the last 12 episodes. The difference is now that the actual “story” has been wrapped up with Yurippe’s redemption last episode, we’ve pretty much crossed into fanfiction territory, where the nominal plot is just watching our favorite characters hang around for one last big hurrah before sending them off into the great unknown. It’s a chance for the show to truly indulge in the connection we’e formed to Yurippe, Otonashi, Kanade, Hinata, and Naoi, letting the emotion flow freely and easily now that’s officially put all the hard work into making them into complete people. And the reason that approach ends up working as well as it does is that seeing these final five finally get a chance to relax into the people they are is, no bullshit, one of the most magical fucking experiences ever.

See, with all potential threats gone and no more real loose ends left to tie up, the characters no longer have to feel driven by something. They can just exist, and live, and have fun living, and be themselves living, just as they’ve all realized they wanted to all along. And sweet merciful Bhudda, when Jun Maeda gets to just let loose with the sincerity and sweetness of his character interactions, the result is the most giddily uplifting stretch of animation I’ve ever seen. I wasn’t just laughing, I wasn’t just cackling, I was crowing. The first half of this episode fills me with so much overwhelming joy that I legitimately feel like my smile is about to split my face in half. Everyone’s just so fucking happy! They’re able to hang out and interact like normal school kids! Hinata in a stupid principal outfit because he lost at rock paper scissors! Everyone getting flustered by singing the closing song too slowly! Just stupid kids being stupid kids, finally able to enjoy their life! And did I mention they’re all so fucking happy? Kanade’s smiling! The distant, detached loner is finally able to connect with her friends on a direct level! And she’s smiling and laughing and being so thrice-damned adorable! The Mapo Tofu school anthem! God, my cheeks still hurt from laughing at that! And all the effort she put into the graduation ceremony and how proud she is of what she’s been able to accomplish and her humming along to Iwasawa’s final song showing how much she always cared about them and that way she hides behind Big Sis Yurippe when Hinata’s mouthing off at her and GOD!

OH, AND SPEAKING OF YURIPPE! You thought you couldn’t love her any more after she came to terms with her life and finally let her defenses down? Well, you were wrong, because now we finally get to see Yuri living as a normal girl, and I swear to fucking god, she makes me shake from sheer, concentrated cute! Finally, she gets to be flustered and frantic and wild and uninhibited! Finally, she gets to live the silly, stupid life she always deserved to live! Finally she gets to be happy! So absurdly, ridiculously, adorably, achingly happy! To see this person who’s been hurting for so long no longer need to put on a brave face for everyone’s sake? To let herself collapse into the biggest, most glorious human disaster of all time? Knowing that she’s freer and fuller than she’s ever been? God, I just- GOD! It’s fucking amazing, what else do you want from me? It’s the single happiest thing in the entire damn show! It’s so stunningly joyous and fervent in just letting Yurippe be, without the need to apologize for herself or fit herself into some standard that she holds herself to, and it makes you truly appreciate how far she’s come. This episode makes you appreciate how far everyone’s come. How much more alive they seem now. How confident and happy they’ve become. How much they all mean to each other.

Which only makes it hurt all the worse when you realize that it’s time to finally say goodbye.

Never Forget

Because once all the laughter is over, once all the gags are finally laid to rest and the ceremony draws to a close, the inevitable truth finally starts to set in: this is it. This is the last these characters will ever see of each other. This is the last we’ll ever see of them. And the more time we spend with them in these final moments, the more gut-twisting the thought of that final farewell becomes. And Angel Beats knows how much you’re suffering. It drags that pain out as long as it humanly can, like slowly peeling a band-aid off a still-open wound, each small jolt forward sending another, stronger spasm of agony through you until there’s no way to possibly hold back your tears. Because we don’t want to leave these idiots behind. We don’t want to bid them goodbye. But we have to. Because that’s the only way they can truly be happy.

And all that emotion is perfectly summed up in Otonashi’s closing graduation speech. As he speaks of the time he’s spent here, all the people he’s met and everything they’ve learned together, his voice grows increasingly halting, increasingly choked up. It becomes harder and harder to get the words out as the memories of all the friends he’s saying goodbye to become stronger and stronger. And as the camera pans across the symbols of the Afterlife Battlefront’s time there, of everyone who’s already passed on- Shiina’s wind-up toys, Takeyama’s computer, TK’s dancing hall, Noda’s ax, Iwasawa and Yui’s guitars- you’re hit with a single, inescapable truth: you care about each and every one of these idiots. It was in this moment, the first time through, that I truly understood what an unparalleled storyteller this show actually was, when I realized just how densely woven the narrative was; in just thirteen episodes, I had come to care so immensely for each and every single member of the Afterlife Brigade that I was driven to tears just by seeing the mementos they left behind. I missed them all as much as Otonashi missed them. I treasured my memories with them as much as he did. I was just as unable to hold back my tears upon realizing that they were truly gone. Because that’s how fucking efficiently this show makes you care about this simple, spectacular cast. That’s how it makes you feel the weight of every single one of their absences.

And once it gets to the five remaining characters? When it’s time to bid them farewell at last? God. God, god, god. If I was crying before, I never cease to end up sobbing at this point. Naoi’s choked-up expression of gratitude toward Otonashi completely makes up for how truncated his arc initially felt. Yurippe’s extension of friendship toward Kanade got me even harder the second time. There’s just no escaping how raw and honest these moments feel, how full of warmth and light these final farewells are (in no small part thanks to the incredible performances; god, Megumi Ogata utterly wrecks me here). It’s too genuine not to connect to. It’s too sincere not to feel for. It’s too true to life not to feel like it’s your own friends who are saying goodbye as they move on to wherever life ends up taking them next. It doesn’t just feel like the characters are moving on; it feels like you’re moving on too, with all the complicated feelings that entails. You don’t want to say goodbye, but you know that it’s for the best, and those conflicting emotions play havoc on your heart until it finally breaks and spills out to stain your cheeks. It’s soul-crushing and soul-saving at the same time, the perfect tonal contradiction.

It’s also the perfect representation of what makes Angel Beats so special to me.

Life is Beautiful

Because when I think back on Angel Beats, all the time I’ve spent with it, watching it, thinking about it, crying over it, there’s one conclusion that I always come back to. Angel Beats is a show about the meaning of life, and the reason it works so fucking well is that it captures the feeling of life better than any other fictional property I’ve seen. It captures the hectic, madcap, unfair, absurd, impossible, evocative, overwhelming, beautiful way that life flows with more honesty and more truth than I’ve ever seen. Life is exactly as crazy as it is in Angel Beats. It’s jam-packed of things that don’t make sense, things that come out of nowhere, confusing emotions and even more confusing leaps between those emotions. You can be laughing one second and crying your eyes out the next. Things go wrong, and sometimes they can’t be fixed, but sometimes they can. Some friends you’ll learn their entire life story, and some friends you’ll barely know a thing about. Things aren’t always fair, and they aren’t always easy. Often times, you won’t see the way your day is going to go until you get there. Sometimes, the whole thing will seem impossible to understand, like it shouldn’t even work. But eventually, you have to move on to whatever life has in store for you next, and it’s only then that you truly realize how meaningful all the time you’ve spent here was. And as much as you might want to stay in place, soaking in that feeling forever, as hard as it becomes to leave... you have to move on.

Because life is too beautiful for anything else.

It’s this ethos that makes Jun Maeda so special to me. He’s a writer who doesn’t just seek to describe life, but to recreate it, in all its inconsistencies, contradictions, and resonance. As absurd as his stories are, they are always so, so true to the universal experience of living. How chaotic it can be, how maddening it can be, how unfair it can be, and how overwhelmingly majestic it can be. And Angel Beats, by making every single second of its narrative count, by allowing Maeda to pour every ounce of his heart and soul into this property from the group up, by using its unreal scenario to explore the reality of its universe, captures that feeling perfectly. No other show connects as deeply to my understanding of the world. No other show makes me feel like I understand my own place in this massive universe a little better every time I watch it. It’s the kind of lightning in a bottle that’s impossible to recapture a second time; the specifics of its makeup are just too fucking particular to ever work the same way again.

That’s why Kanade refuses to stay with Otonashi when everyone else has passed on. That’s why, despite his confession of love, she knows them staying here would be the wrong choice. They have to move on. There’s too much potential good waiting for them up ahead to stay as they are. She has to move on. She has to pull him along with her, has to keep him from staying behind in a world where he will only ever stay stagnant and lonely. She has to believe that they’re both worth continuing on. That they’re both worth being who they have the potential to be.

She has to believe... that life is beautiful.

Which leads me to my single favorite moment of the entire fucking show.

My Soul, Your Beats

Jun Maeda is a writer who is not as beloved by everyone as he is by me. His style is high on melodrama and emotionality, and it requires a willingness from the audience to let their defenses down and let the sincerity of his narratives work their magic. And not everyone can handle that level of vulnerability and lack of presumptions. So if you want to judge for yourself whether or not his style works for you, I suggest you watch one of his shows to the end, and then judge your reaction to a very certain plot point in the final episode: the Deus ex Maeda. Admittedly, I’m not sure if any of his shows outside After Story and Angel Beats share this trait, but at the very least it’s a storytelling device he clearly has an affinity for. At the end of his stories, he will often include, as part of the central emotional catharsis, a plot point that requires an extremely flexible appreciation of logic to connect to. It’s a story beat that can only just barely be justified by the mechanics of the world he’s set up, but is also integral to the themes the story is trying to present. So the question becomes: how much do you buy into the emotions of the Deus ex Maeda, despite its tenuous grasp on logic? Where you fall on that question will be the clearest possible sign as to how completely you can give yourself over to Jun Maeda’s writing style. If you don’t connect with it, the moment in question will seem out of place and jarring in the worst way. But if you do connect with it, the result with be a moment of transcendence so pure that you might as well have ascended to heaven on the spot.

From a logical standpoint, it makes no sense that Kanade ended up with Otonashi’s heart following his death and presumed Organ Donor status. Kanade was in this world far before Otonashi was, but the timeline at play requires that Otonashi die far before Kanade. Thanks to the wibbly mechanics of afterlife rules, it can be handwaved efficiently enough by any justification you can think of: maybe, for example, Otonashi did die first, but was only sent over much later once the Afterlife Battlefront started becoming a problem that needed a solution? It’s not a completely impossible scenario, is my point. It’s just a highly implausible one, one that isn’t even explained in universe and is just left to hang around as an eternally unanswered question. And such a moment has a high risk of breaking the audience’s immersion at the single most emotional moment of the entire show.

But for me, it didn’t matter.

It didn’t matter that the logic was frayed. it didn’t matter that there wasn’t a concrete explanation. Because the meaning it had for the characters and their emotions was so palpable, so awe-inspiring, that even as I realized the logical issue in the moment, my brain literally shut that skeptical voice down to keep it from interfering with my emotional journey. Yes, this moment literally made me turn my brain off. Because the thematic resonance of Otonashi’s life having meaning even beyond his death, just as he wished for in those final moments in the tunnel, is too fucking powerful to be stymied by logic. This. Reveal. Is. PERFECT. It’s the perfect capstone on Kanade and Otonashi’s journeys. It’s the perfect connection between them, the perfect justification for why they ended up falling in love. It makes the title Angel Beats itself suddenly make sense, and that realization alone is primordially colossal enough to excuse any discrepancies. Otonashi saved Kanade’s life. He gave her another chance to live the life she deserved to live. He exists within her. His life has meaning with her. And now, it’s her turn to give his life meaning, to give back the thanks she could never share with him in life.

To make him realize that life is beautiful.

Ladies, gentlemen, and everyone in between, this is, without a doubt, the single greatest coda in anime history. This beautiful, overwhelming, perfect revelation sets my soul ablaze with the fires of heaven and earth alike. Tears don’t begin to do justice to the effect Kanade’s beating heart has on me; my reaction is something closer to coming up gasping for air from an ocean I’ve cried out myself. It overwhelms me, breaks me, mends me, and leaves me floating blissfully upon the waves of rapture like nothing else does. And from then on, there’s nothing left to do but sob and sob and sob in pure, unadulterated joy and sadness combined, through Kanade’s desperate please, sounding more alive than she ever has, Otonashi’s despair at realizing the enormity of what he must do, saying “I love you” once more, convincing Kanade beyond any reasonable doubt that life is, indeed, beautiful, Kanade’s utterly soul-wrenching goodbye, the swelling of My Most Precious Treasure in a final, triumphant echo as Otonashi screams to the heavens, that last ED shot as this time, Kanade has finally joined her friends, and they all fade away this time until only she and Otonashi remain, and then Kanade vanishes too, and you’re left hovering for five agonizing, horrifying seconds as you wait with baited breath, praying for Otonashi to follow after her...

And he finally does, leaving the afterlife empty as the final notes of the song play, only for them to find each other once again in their next life, everything fading to white as Otonashi reaches out for her, to remember that life is beautiful all over again. And by that time, you might as well pour yourself a gallon of water, because chances are you’re completely dehydrated from crying at that point. You’ve finally reached the end, and you can’t help but come out of it feeling nothing more or less than reborn alongside the Afterlife Brigade. It’s the perfect closure, the perfect goodbye, the perfect ending to an all-but-perfect story. What a magical, transcendent, sacred experience. What a one-of-a-kind show. Sayonara, Angel Beats. Thank you for helping me see that life is beautiful.

And we’re done. Holy cats. Okay, well, expect my re-watch reflection in a little bit!

#anime#the anime binge-watcher#tabw#angel beats#yuzuru otonashi#kanade tachibana#yuri nakamura#yurippe#kanade x otonashi#hideki hinata#angel beats yui#angel beats tk#masami iwasawa#ayato naoi#angel beats rw

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Short Peace - Hiroaki Ando, Hajime Katoki, 森田修平 & Katsuhiro Otomo

Short Peace is an omnibus collection of four anime shorts, including the 86th Academy Award nominated Best Animated Short Film Possessions, directed by Shuhei Morita. Short Peace is the first film release in over nine years from Katsuhiro Otomo. In 1995, Katsuhiro Otomo’s epic anthology Memories showcased the work of upcoming superstars of the anime world. Now, Otomo’s spotlight shifts to a fresh generation of master creators with an all-new anthology of visionary films: A lone traveler is confronted by unusual spirits in an abandoned shrine in Possessions (Tsukumo), directed by Shuhei Morita (Coicent, Kakurenbo). A mysterious white bear defends the royal family from the predations of a red demon in the brutal Gambo, directed by Hiroaki Ando (Five Numbers!) from Redline’s Katsuhito Ishii’s original story with character designs by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto (Neon Genesis Evangelion). The focus shifts from supernatural to science fiction for the action packed A Farewell To Weapons (Buki Yo Saraba), as Mobile Suit Gundam designer Hajime Katoki helms Otomo’s tour-de-force saga of men battling robotic tanks in apocalyptic Tokyo, while grandmaster Otomo himself assumes the directorial reigns for a spectacular tale of love, honor and firefighting in ancient Japan with the multi-award winning Combustible (Hi-No-Youjin). http://dlvr.it/Qy0tkb

0 notes

Text

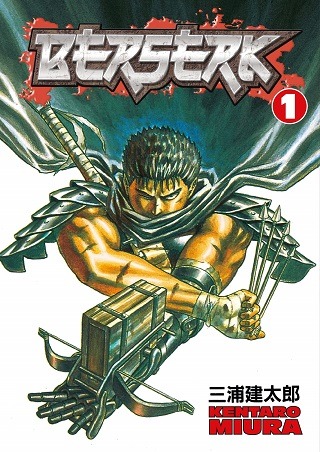

ESSAY: Berserk's Journey of Acceptance Over 30 Years of Fandom

My descent into anime fandom began in the '90s, and just as watching Neon Genesis Evangelion caused my first revelation that cartoons could be art, reading Berserk gave me the same realization about comics. The news of Kentaro Miura’s death, who passed on May 6, has been emotionally complicated for me, as it's the first time a celebrity's death has hit truly close to home. In addition to being the lynchpin for several important personal revelations, Berserk is one of the longest-lasting works I’ve followed and that I must suddenly bid farewell to after existing alongside it for two-thirds of my life.

Berserk is a monolith not only for anime and manga, but also fantasy literature, video games, you name it. It might be one of the single most influential works of the ‘80s — on a level similar to Blade Runner — to a degree where it’s difficult to imagine what the world might look like without it, and the generations of creators the series inspired.

Although not the first, Guts is the prototypical large sword anime boy: Final Fantasy VII's Cloud Strife, Siegfried/Nightmare from Soulcalibur, and Black Clover's Asta are all links in the same chain, with other series like Dark Souls and Claymore taking clear inspiration from Berserk. But even deeper than that, the three-character dynamic between Guts, Griffith, and Casca, the monster designs, the grotesque violence, Miura’s image of hell — all of them can be spotted in countless pieces of media across the globe.

Despite this, it just doesn’t seem like people talk about it very much. For over 20 years, Berserk has stood among the critical pantheon for both anime and manga, but it doesn’t spur conversations in the same way as Neon Genesis Evangelion, Akira, or Dragon Ball Z still do today. Its graphic depictions certainly represent a barrier to entry much higher than even the aforementioned company.

Seeing the internet exude sympathy and fond reminiscing about Berserk was immensely validating and has been my single most therapeutic experience online. Moreso, it reminded me that the fans have always been there. And even looking into it, Berserk is the single best-selling property in the 35-year history of Dark Horse. My feeling is that Berserk just has something about it that reaches deep into you and gets stuck there.

I recall introducing one of my housemates to Berserk a few years ago — a person with all the intelligence and personal drive to both work on cancer research at Stanford while pursuing his own MD and maintaining a level of physical fitness that was frankly unreasonable for the hours that he kept. He was NOT in any way analytical about the media he consumed, but watching him sitting on the floor turning all his considerable willpower and intellect toward delivering an off-the-cuff treatise on how Berserk had so deeply touched him was a sight in itself to behold. His thoughts on the series' portrayal of sex as fundamentally violent leading up to Guts and Casca’s first moment of intimacy in the Golden Age movies was one of the most beautiful sentiments I’d ever heard in reaction to a piece of fiction.

I don’t think I’d ever heard him provide anything but a surface-level take on a piece of media before or since. He was a pretty forthright guy, but the way he just cut into himself and let his feelings pour out onto the floor left me awestruck. The process of reading Berserk can strike emotional chords within you that are tough to untangle. I’ve been writing analysis and experiential pieces related to anime and manga for almost ten years — and interacting with Berserk’s world for almost 30 years — and writing may just be yet another attempt for me to pull my own twisted-up feelings about it apart.

Berserk is one of the most deeply personal works I’ve ever read, both for myself and in my perception of Miura's works. The series' transformation in the past 30 years artistically and thematically is so singular it's difficult to find another work that comes close. The author of Hajime no Ippo, who was among the first to see Berserk as Miura presented him with some early drafts working as his assistant, claimed that the design for Guts and Puck had come from a mess of ideas Miura had been working on since his early school days.

写真は三浦建太郎君が寄稿してくれた鷹村です。 今かなり感傷的になっています。 思い出話をさせて下さい。 僕が初めての週刊連載でスタッフが一人もいなくて困っていたら手伝いにきてくれました。 彼が18で僕が19です。 某大学の芸術学部の学生で講義明けにスケッチブックを片手に来てくれました。 pic.twitter.com/hT1JCWBTKu

— 森川ジョージ (@WANPOWANWAN) May 20, 2021

Miura claimed two of his big influences were Go Nagai’s Violence Jack and Tetsuo Hara and Buronson’s Fist of the North Star. Miura wears these influences on his sleeve, discovering the early concepts that had percolated in his mind just felt right. The beginning of Berserk, despite its amazing visual power, feels like it sprang from a very juvenile concept: Guts is a hypermasculine lone traveler breaking his body against nightmarish creatures in his single-minded pursuit of revenge, rigidly independent and distrustful of others due to his dark past.

Uncompromising, rugged, independent, a really big sword ... Guts is a romantic ideal of masculinity on a quest to personally serve justice against the one who wronged him. Almost nefarious in the manner in which his character checked these boxes, especially when it came to his grim stoicism, unblinkingly facing his struggle against literal cosmic forces. Never doubting himself, never trusting others, never weeping for what he had lost.

Miura said he sketched out most of the backstory when the manga began publication, so I have to assume the larger strokes of the Golden Arc were pretty well figured out from the outset, but I’m less sure if he had fully realized where he wanted to take the story to where we are now. After the introductory mini-arcs of demon-slaying, Berserk encounters Griffith and the story draws us back to a massive flashback arc. We see the same Guts living as a lone mercenary who Griffith persuades to join the Band of the Hawk to help realize his ambitions of rising above the circumstances of his birth to join the nobility.

We discover the horrific abuses of Guts’ adoptive father and eventually learn that Guts, Griffith, and Casca are all victims of sexual violence. The story develops into a sprawling semi-historical epic featuring politics and war, but the real narrative is in the growing companionship between Guts and the members of the band. Directionless and traumatized by his childhood, Guts slowly finds a purpose helping Griffith realize his dream and the courage to allow others to grow close to him.

Miura mentioned that many Band of the Hawk members were based on his early friend groups. Although he was always sparse with details about his personal life, he has spoken about how many of them referred to themselves as aspiring manga authors and how he felt an intense sense of competition, admitting that among them he may have been the only one seriously working toward that goal, desperately keeping ahead in his perceived race against them. It’s intriguing thinking about how much of this angst may have made it to the pages, as it's almost impossible not to imagine Miura put quite a bit of himself in Guts.

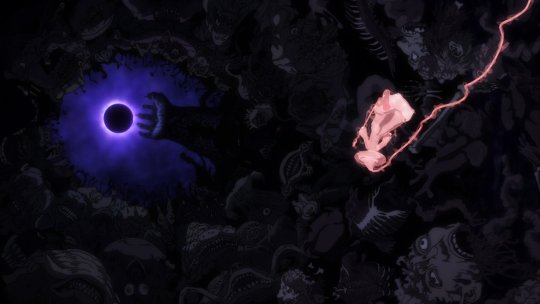

Perhaps this is why it feels so real and makes The Eclipse — the quintessential anime betrayal at the hands of Griffith — all the more heartbreaking. The raw violence and macabre imagery certainly helped. While Miura owed Hellraiser’s Cenobites much in the designs of the God Hand, his macabre portrayal of the Band of the Hawk’s eradication within the literal bowels of hell, the massive hand, the black sun, the Skull Knight, and even Miura’s page compositions have been endlessly referenced, copied, and outright plagiarized since.

The events were tragic in any context and I have heard many deeply personal experiences others drew from The Eclipse sympathizing with Guts, Casca, or even Griffith’s spiral driven by his perceived rejection by Guts. Mine were most closely aligned with the tragedy of Guts having overcome such painful circumstances to not only reject his own self enforced solitude, but to fearlessly express his affection for his loved ones.

The Golden Age was a methodical destruction of Guts’ self-destructive methods of preservation ruined in a single selfish act by his most trusted friend, leaving him once again alone and afraid of growing close to those around him. It ripped the romance of Guts’ mission and eventually took the story down a course I never expected. Berserk wasn’t a story of revenge but one of recovery.

Guess that’s enough beating around the bush, as I should talk about how this shift affected me personally. When I was young, when I began reading Berserk I found Guts’ unflagging stoicism to be really cool, not just aesthetically but in how I understood guys were supposed to be. I was slow to make friends during school and my rapidly gentrifying neighborhood had my friends' parents moving away faster than I could find new ones. At some point I think I became too afraid of putting myself out there anymore, risking rejection when even acceptance was so fleeting. It began to feel easier just to resign myself to solitude and pretend my circumstances were beyond my own power to correct.

Unfortunately, I became the stereotypical kid who ate alone during lunch break. Under the invisible expectations demanding I not display weakness, my loneliness was compounded by shame for feeling loneliness. My only recourse was to reveal none of those feelings and pretend the whole thing didn't bother me at all. Needless to say my attempts to cope probably fooled no one and only made things even worse, but I really didn’t know of any better way to handle my situation. I felt bad, I felt even worse about feeling bad and had been provided with zero tools to cope, much less even admit that I had a problem at all.

The arcs following the Golden Age completely changed my perspective. Guts had tragically, yet understandably, cut himself off from others to save himself from experiencing that trauma again and, in effect, denied himself any opportunity to allow himself to be happy again. As he began to meet other characters that attached themselves to him, between Rickert and Erica spending months waiting worried for his return, and even the slimmest hope to rescuing Casca began to seed itself into the story, I could only see Guts as a fool pursuing a grim and hopeless task rather than appreciating everything that he had managed to hold onto.

The same attributes that made Guts so compelling in the opening chapters were revealed as his true enemy. Griffith had committed an unforgivable act but Guts’ journey for revenge was one of self-inflicted pain and fear. The romanticism was gone.

Farnese’s inclusion in the Conviction arc was a revelation. Among the many brilliant aspects of her character, I identified with her simply for how she acted as a stand-in for myself as the reader: Plagued by self-doubt and fear, desperate to maintain her own stoic and uncompromising image, and resentful of her place in the world. She sees Guts’ fearlessness in the face of cosmic horror and believes she might be able to learn his confidence.

But in following Guts, Farnese instead finds a teacher in Casca. In taking care of her, Farnese develops a connection and is able to experience genuine sympathy that develops into a sense of responsibility. Caring for Casca allows Farnese to develop the courage she was lacking not out of reckless self-abandon but compassion.

I can’t exactly credit Berserk with turning my life around, but I feel that it genuinely helped crystallize within me a sense of growing doubts about my maladjusted high school days. My growing awareness of Guts' undeniable role in his own suffering forced me to admit my own role in mine and created a determination to take action to fix it rather than pretending enough stoicism might actually result in some sort of solution.

I visited the Berserk subreddit from time to time and always enjoyed the group's penchant for referring to all the members of the board as “fellow strugglers,” owing both to Skull Knight’s label for Guts and their own tongue-in-cheek humor at waiting through extended hiatuses. Only in retrospect did it feel truly fitting to me. Trying to avoid the pitfalls of Guts’ path is a constant struggle. Today I’m blessed with many good friends but still feel primal pangs of fear holding me back nearly every time I meet someone, the idea of telling others how much they mean to me or even sharing my thoughts and feelings about something I care about deeply as if each action will expose me to attack.

It’s taken time to pull myself away from the behaviors that were so deeply ingrained and it’s a journey where I’m not sure the work will ever be truly done, but witnessing Guts’ own slow progress has been a constant source of reassurance. My sense of admiration for Miura’s epic tale of a man allowing himself to let go after suffering such devastating circumstances brought my own humble problems and their way out into focus.

Over the years I, and many others, have been forced to come to terms with the fact that Berserk would likely never finish. The pattern of long, unexplained hiatuses and the solemn recognition that any of them could be the last is a familiar one. The double-edged sword of manga largely being works created by a single individual is that there is rarely anyone in a position to pick up the torch when the creator calls it quits. Takehiko Inoue’s Vagabond, Ai Yazawa’s Nana, and likely Yoshihiro Togashi’s Hunter X Hunter all frozen in indefinite hiatus, the publishers respectfully holding the door open should the creators ever decide to return, leaving it in a liminal space with no sense of conclusion for the fans except what we can make for ourselves.

The reason for Miura’s hiatuses was unclear. Fans liked to joke that he would take long breaks to play The Idolmaster, but Miura was also infamous for taking “breaks” spent minutely illustrating panels to his exacting artistic standard, creating a tumultuous release schedule during the wars featuring thousands of tiny soldiers all dressed in period-appropriate armor. If his health was becoming an issue, it’s uncommon that news would be shared with fans for most authors, much less one as private as Miura.

Even without delays, the story Miura was building just seemed to be getting too big. The scale continued to grow, his narrative ambition swelling even faster after 20 years of publication, the depth and breadth of his universe constantly expanding. The fan-dubbed “Millennium Falcon Arc” was massive, changing the landscape of Berserk from a low fantasy plagued by roaming demons to a high fantasy where godlike beings of sanity-defying size battled for control of the world. How could Guts even meet Griffith again? What might Casca want to do when her sanity returned? What are the origins of the Skull Knight? And would he do battle with the God Hand? There was too much left to happen and Miura’s art only grew more and more elaborate. It would take decades to resolve all this.

But it didn’t need to. I imagine we’ll never get a precise picture of the final years of Miura’s life leading up to his tragic passing. In the final chapters he released, it felt as if he had directed the story to some conclusion. The unfinished Fantasia arc finds Guts and his newfound band finding a way to finally restore Casca’s sanity and — although there is still unmistakably a boundary separating them — both seem resolute in finding a way to mend their shared wounds together.

One of the final chapters features Guts drinking around the campfire with the two other men of his group, Serpico and Roderick, as he entrusts the recovery of Casca to Schierke and Farnese. It's a scene that, in the original Band of the Hawk, would have found Guts brooding as his fellows engage in bluster. The tone of this conversation, however, is completely different. The three commiserate over how much has changed and the strength each has found in the companionship of the others. After everything that has happened, Guts declares that he is grateful.

The suicidal dedication to his quest for vengeance and dispassionate pragmatism that defined Guts in the earliest chapters is gone. Although they first appeared to be a source of strength as the Black Swordsman, he has learned that they rose from the fear of losing his friends again, from letting others close enough to harm him, and from having no other purpose without others. Whether or not Guts and Griffith were to ever meet again, Guts has rediscovered the strength to no longer carry his burdens alone.

All that has happened is all there will ever be. We too must be grateful.

Peter Fobian is an Associate Manager of Social Video at Crunchyroll, writer for Anime Academy and Anime in America, and an editor at Anime Feminist. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterFobian.

By: Peter Fobian

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

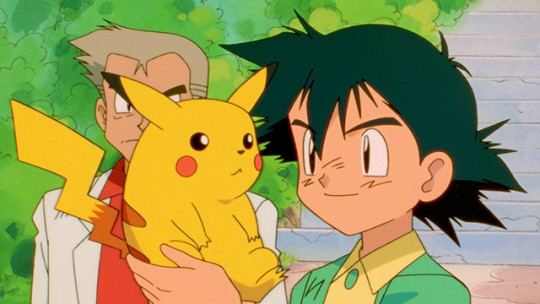

FEATURE: Why The Early Pokémon Anime Was So Important To Its Audience

The '90s was a big decade for anime. Iconic series like Neon Genesis Evangelion and Cowboy Bebop were born, shows that are still presented as the gold standard of what the medium can achieve. Studio Ghibli continued their string of soon-to-be classics, helping to cement Hayao Miyazaki into a globally-recognized “auteur” status, a title usually reserved for the creators of live-action fare. Meanwhile, Dragon Ball Z, Gundam Wing, and others made their debut on the programming block Toonami, effectively introducing anime to an entire generation of Americans who may have otherwise never been exposed to it.

But what about the importance of Pokémon? That was pretty big, too, right?

Obviously, the status of the Pokémon anime as it relates to Pokémon as a whole is clear. There has perhaps never been a franchise with more coherent brand synergy, none better at directing traffic so fans of one aspect could be easily guided to another. Aided by an almost supernaturally compelling catchphrase “Gotta catch ‘em all!,” the uncertain development and angst surrounding the first set of titles in the core game series Red and Blue were quickly left in the rearview mirror. Pokémon is seemingly an undefeatable pop culture hydra with the anime serving as one of its many heads.

So how does Pokémon fit in the grand scheme of anime and what it can give to us? Because with all of that in mind, it’s hard not to look at it with a kind of cynicism, viewing it less as a fictional series with all the pros and cons that come with it, and more as an advertisement for itself and other parts of the franchise that has lasted over 20 years. However, I believe the Pokémon anime can be, depending on the specific section, very good at times. And though the explosion of “Pokemania,” as it was dubbed when the franchise landed in the United States, seemed to render it as an extended commercial urging kids to get their parents to buy them a Game Boy as soon as the "PokeRap" finished, I think the early parts of the series are particularly strong.

Because while the anime has formed a kind of cyclical pattern in its storytelling, one that allows newcomers to easily latch onto the series whenever they happen to discover it, I think the portions set in Kanto and Johto are extremely cool to examine. The space from the first time Ash Ketchum wakes up too late to grab one of the three “starter” Pokémon from Professor Oak to the time he says goodbye to Misty and Brock at the crossroads following the Silver Conference contains a really touching narrative. One about growing up and learning to rely on others and then, eventually, learning to rely on yourself.

When we first meet Ash, he can barely keep things together. He’s desperate to be a Pokémon Master, but clueless when it comes to most of the techniques involved in actually doing that. He’s stubborn, but his confidence often reveals itself to be brittle bravado, a ten-year-old puffing his chest out only to be deflated when overtaken by an obstacle. His travel partners, Misty and Brock (and Tracey Sketchit for a little while,) obviously adore him, but their greatest shared trait is likely patience. Ash has a lot of learning to do.

This learning is usually slow and painstaking. Critics of the series are often quick to point out that Ash rarely wins his gym battles outright, something that’s a requirement to progress in the games the series is based on. Thus, more important than a solid KO is the lesson learned due to the battle, often something centered around taking care of your Pokémon, yourself, and other people. The “monster of the week” structure usually has Ash learning these lessons again and again, like a child that needs to be politely reprimanded until they fall out of a bad habit.

As the series moves from Kanto to the Johto region, Ash gains legitimate wins with higher frequency, gathering experience while his style remains eager, clumsy, and definitively Ash. His rivalry with Gary Oak — one initially informed by Ash’s seeming inadequacy and Gary’s loud, yet often precise assurance — evens out. At the end of the Indigo League in the Kanto region, Ash finally gets to battle Gary and loses. Then, in the Johto League tournament, Ash defeats Gary and the two make amends thanks to Ash’s defeat of his bully and Gary’s newfound serenity. It’s a nice payoff to their relationship, and Gary’s change of heart reflects the themes of personal growth found in the Original Series.

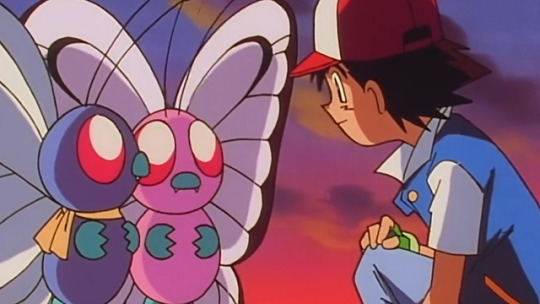

Meanwhile, Ash’s personal growth often comes with much more heartache. In “Bye Bye Butterfree,” he bids farewell to his first-ever caught monster because it would be happier with its own kind. A few episodes later, in “Pikachu’s Goodbye,” he seems all too ready to let Pikachu live with a pack of the little yellow critters, likely because his experience with Butterfree indicated that it was the right thing to do. Of course, Pikachu comes back to him, because he’s Ash’s ride or die.

Another relationship Ash learns from is the one with Charizard. Evolved from an abandoned and emotionally distraught Charmander, Charizard is rebellious to the extent that it causes Ash’s Indigo League loss, not because it gets knocked out but because it just doesn’t feel like fighting anymore. What follows is one of the most disheartening scenes in the series, with Ash shouting in anger and sadness at his Charizard to continue while Charizard just doesn’t respect his trainer enough to stand up. Though they eventually gain a sense of mutual reverence, their partnership is marked by this uncertainty.

And finally, the ending, which sees Ash, Misty, and Brock go their separate ways, recalls one of the franchise’s most resonant homages, that of the '80s film Stand By Me. Referenced in the opening moments of the first game, the movie about setting off on your own adventure as a youth and learning where nostalgia ends and the harshness of growing up begins mirrors the ethos of the franchise constantly. At the end of that film, the characters depart one another and the main protagonist muses to himself, “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?”

You can get the same feeling from the affirmations of the importance of their friendship Ash, Brock, and Misty make when they head off on their own (though Brock quickly re-joins Ash in the next season of the anime). It’s here that Pokémon displays why it deserves its place among the notable anime of the '90s, not because of its massive marketing push (though that certainly helped its popularity) and not because of how it retold the story of the games (which, as adaptations go, is pretty hit or miss).

.

Instead, it’s a story about growing up. By the end of Ash’s time in Johto, it becomes clear that strength was never the objective, that the point of the whole affair was not Ash becoming a "Master." It was about teaching Ash enough so that when the time came for him to go out on his own, he could. And though he finds new companions in the regions to come pretty quickly, the impact of this is not diminished. If you began watching the show when it first appeared in America in 1998, you likely grew up with Ash to an extent, and you likely experienced some major life events during that time, whether it was going to a new school or facing some kind of family change or attempting to achieve some new, grand goal.

Ash and the Pokémon anime’s message was that you could do it. That the trials you’d experienced and the lessons you’d learned and the relationships you’d made had prepared you for it. And that while the future seems scary and unknowable, it isn’t insurmountable. Pokémon teaches you that you’ll be okay. That sounds pretty important to me.

Daniel Dockery is a Senior Staff Writer for Crunchyroll. Follow him on Twitter!

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

By: Daniel Dockery

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Short Peace - Hiroaki Ando, Hajime Katoki, 森田修平 & Katsuhiro Otomo

Short Peace is an omnibus collection of four anime shorts, including the 86th Academy Award nominated Best Animated Short Film Possessions, directed by Shuhei Morita. Short Peace is the first film release in over nine years from Katsuhiro Otomo. In 1995, Katsuhiro Otomo’s epic anthology Memories showcased the work of upcoming superstars of the anime world. Now, Otomo’s spotlight shifts to a fresh generation of master creators with an all-new anthology of visionary films: A lone traveler is confronted by unusual spirits in an abandoned shrine in Possessions (Tsukumo), directed by Shuhei Morita (Coicent, Kakurenbo). A mysterious white bear defends the royal family from the predations of a red demon in the brutal Gambo, directed by Hiroaki Ando (Five Numbers!) from Redline’s Katsuhito Ishii’s original story with character designs by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto (Neon Genesis Evangelion). The focus shifts from supernatural to science fiction for the action packed A Farewell To Weapons (Buki Yo Saraba), as Mobile Suit Gundam designer Hajime Katoki helms Otomo’s tour-de-force saga of men battling robotic tanks in apocalyptic Tokyo, while grandmaster Otomo himself assumes the directorial reigns for a spectacular tale of love, honor and firefighting in ancient Japan with the multi-award winning Combustible (Hi-No-Youjin). http://dlvr.it/NhqvHc

0 notes